Abstract

Microglial cell phagocytic receptors may play important roles in the pathogenesis and treatment of several neurological diseases. We studied microglial Fc receptor (FcR) activation with respect to the specific FcγR types involved and the downstream signaling events by using monoclonal antibody (MAb)-coated Cryptococcus neoformans immune complexes as the stimuli and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α) production as the final outcome. C. neoformans complexed with murine immunoglobulin G (IgG) of γ1, γ2a, and γ3, but not γ2b isotype, was effective in inducing MIP-1α in human microglia. Since murine γ2b binds to human FcγRII (but not FcγRI or FcγRIII), these results indicate that FcγRI and/or FcγRIII is involved in MIP-1α production. Consistent with this, an antibody that blocks FcγRII (IV.3) failed to inhibit MIP-1α production, while an antibody that blocks FcγRIII (3G8) did. An anti-C. neoformans MAb, 18B7 (IgG1), but not its F(ab′)2, induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase phosphorylation, and MIP-1α release was suppressed by the ERK inhibitor U0126. C. neoformans plus 18B7 also induced degradation of I-κBα, and MIP-1α release was suppressed by the antioxidant NF-κB inhibitor pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate. To confirm the role of FcR more directly, we isolated microglia from wild-type and various FcR-deficient mice and then challenged them with C. neoformans plus 18B7. While FcγRII-deficient microglia showed little difference from the wild-type microglia, both FcγRI α-chain- and FcγRIII α-chain-deficient microglia produced less MIP-1α, and the common Fc γ-chain-deficient microglia showed no MIP-1α release. Taken together, our results demonstrate a definitive role for FcγRI and FcγRIII in microglial chemokine induction and implicate ERK and NF-κB as the signaling components leading to MIP-1α expression. Our results delineate a new mechanism for microglial activation and may have implications for central nervous system inflammatory diseases.

Microglia and macrophages express lineage-specific inflammatory mediators such as interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-1 receptor antagonist, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α), and MIP-1β (22, 33, 35, 44, 46). MIP-1α is a member of a family of small inducible and secreted cytokines, defined by four conserved cysteine residues. Human MIP-1α is ∼75% homologous to murine MIP-1α at the amino acid level, and a higher degree of homology exists in the promoter sequences of the two genes (19). A role of MIP-1α as an inflammatory mediator is suggested by its function as a chemoattractant. In addition, other β-chemokines, MIP-1β, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, and RANTES, are also potent chemotactic agents for monocytes. An additional role for β-chemokines has been discovered for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) diseases; i.e., MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES modulate HIV-1 infection of T cells and macrophages by competing for the viral receptor CCR5 (2, 21). Therefore, the regulation of β-chemokines is pivotal in the overall orchestration of the inflammatory responses in the target organ.

Cryptococcus neoformans is a fungal pathogen that is remarkable for its ability to cause central nervous system (CNS) infections (5, 6, 8, 11). C. neoformans elicits a wide range of tissue responses (29) which can be attributed to both host immune status and the characteristics of fungal cells. Microglia play a central role in the host response in cryptococcal meningoencephalitis (29). Microglia phagocytose C. neoformans in vivo and in vitro and modulate the fate of fungal cells. C. neoformans and its soluble capsular polysaccharide glucuronoxylomannan (GXM) alter microglial cell growth and inflammatory gene expression (18, 31). Opsonins such as complement and specific antibodies are important because C. neoformans interacts with microglia through these molecules. However, little is known about the mechanisms by which antibody- or complement-opsonized C. neoformans modulates microglial immune responses.

We have previously shown that, in primary human microglial cultures, C. neoformans induces multiple chemokine genes including genes for MIP-1α, MIP-1β, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, and IL-8 in the presence of specific antibodies (18). Robust expression of MIP-1α and MIP-1β proteins was detected as early as 4 h after exposure to C. neoformans immune complexes, which could be inhibited by herbimycin A. Furthermore, the effect of C. neoformans immune complexes could not be mimicked by GXM immune complexes but was inhibited by them, confirming the immunosuppressive effects of GXM (12, 18, 27, 39) and suggesting a complex interplay among the fungal cells, soluble polysaccharide, and the opsonins.

Given that antibody therapy with the monoclonal antibody (MAb) 18B7 is currently in clinical evaluation in patients with cryptococcal meningitis, there is an urgent need to understand the interaction of C. neoformans with microglia in the presence and absence of antibody. Our previous studies suggested the involvement of Fc receptors (FcR) in the microglial chemokine response, because (i) C. neoformans-induced chemokine production required specific antibody and (ii) antibody aggregates and immobilized immunoglobulin induced MIP-1α and MIP-1β in the absence of antigen. Involvement of FcɛRI and FcαR in the induction of chemokines has been demonstrated previously for mast cells and mesangial cells (14, 52). In monocytes, coengagement of FcγRI or FcγRII with intercellular adhesion molecule 3 has been shown previously to induce chemokines (26). In this study, we investigated the role of microglial FcR in the C. neoformans-elicited chemokine response, with respect to the specific FcγR types involved and the downstream signaling events. Microglia from various FcR-knockout mice were also investigated to determine the role of specific FcR components in the induction of MIP-1α and phagocytosis. The results suggest a novel pathway by which immune complexes can activate microglia and indicate a mechanism by which passive antibody may influence the course of cryptococcal disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human microglia.

This study is part of an ongoing research protocol that has been approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Committee on Clinical Investigations. Informed consent was obtained from participants. Fetal brains were obtained from elective terminations of pregnancy from healthy women with no risk factors for HIV-1 infection. Fetal microglia were cultivated from second-trimester abortuses as described elsewhere (30, 32). Briefly, the brain tissues were mechanically and enzymatically dissociated and passed through nylon meshes of 130- and 230-μm pore size to generate a suspension of mixed brain cell populations. Cells were seeded at 108 cells per T75-cm2 tissue culture plate in medium (Dulbecco modified Eagle medium [DMEM] with 4.5 g of glucose/liter, 4 mM l-glutamine, and 25 mM HEPES buffer) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (Fungizone; 0.25 μg/ml; Life Technologies, Bethesda, Md.). After 2 weeks of culture, microglia were harvested by aspiration of culture medium, pelleted, and seeded in 96-well culture plates at a density of 4 × 104 cells per well. Microglia medium was the same as mixed culture medium, but without amphotericin B.

Mouse microglia.

Murine microglial cells were cultured from neonatal mice of C57BL/6 background. These included mice deficient in the FcγR common γ-chain gene (γ KO), FcγRI α chain (RI KO), FcγRIII α chain (RIII KO), or FcγRII (RII KO) and wild-type (WT) mice. RI was of 129/C57 background. Briefly, brains from several pups belonging to the same litter were pooled and triturated with a pipette in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS). Tissue fragments were incubated in 0.5× trypsin (Gibco)-D-PBS at 37°C for 20 min and then further triturated by repeated pipetting. Cells were filtered through 230-μm-pore-size nylon mesh and then washed with DMEM-10% fetal calf serum twice. Dissociated cells were then suspended in complete medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 1% antibiotics [Gibco]) and plated at 106 cells/ml in a T75-cm2 tissue culture flask. Cells were cultured at 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator at 37°C for 2 weeks with a weekly change of medium. After 2 weeks of culture, microglial cells were detached from the astrocyte monolayer by vigorous manual shaking. Floating microglial cells were collected by pooling the medium and were suspended in fresh medium and plated at 6 × 105 cells/ml in 96-well plates (0.1 ml per well). One hour later, cultures were washed to remove nonadherent cells. The purity of microglial cultures was determined by immunostaining for CD11b and CD16 (biotinylated mouse MAbs [Becton-Dickinson]; microglia), GSA lectin (peroxidase-conjugated Griffonia simplicifolia [Sigma]; microglia), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP [BioGenix]; astrocytes), and myelin basic protein (Boehringer Mannheim; oligodendrocytes). Cultures were >99% pure microglia.

Organism.

C. neoformans ATCC 24067, a serotype D strain, was used in this study. Serotype D strains are responsible for most cases of cryptococcal meningoencephalitis in certain parts of the world, especially northern Europe. In New York City, serotype D strains make up 15% of clinical cryptococcal isolates (47). This strain was selected for study because it has been extensively studied and was used in our prior investigations. Cells were grown in Sabouraud dextrose broth in a rotary shaker at 30°C until stationary phase. Cells were then washed three times in sterile PBS and counted with a hemocytometer.

Antibodies.

The 18B7 immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) murine MAb that binds GXM was purified with protein G-Sepharose for this study (7, 38). MAb 3E5 was also used because a well-characterized isotype switch family, including the full IgG subclass set (IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3), that was derived from this hybridoma (53) was available. MAbs 18B7 and 3E5 are both class II antibodies that have specificity for GXM, use the same variable regions, and were derived from the same mouse (4). For the purpose of this study MAbs 18B7 and 3E5 (γ1) can be considered equivalent. The F(ab′)2 fragment of 18B7 was generated by using a commercial kit (ImmunoPure; Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (C. P. Taborda and A. Casadevall, Abstr. 101st Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. F-106, p. 376, 2001). The Limulus lysate assay (Bio-Whittaker, Walkersville, Md.) revealed endotoxin levels of <0.1 EU in the antibody preparations. Fab MAbs against human FcγRII (IV.3) and FcγRIII (3G8) were purchased from Medarex (Annandale, N.J.) and added to culture at 1 to 10 μg/ml for 30 min at 4°C before exposure to MAb-opsonized C. neoformans.

Inoculation of microglia with C. neoformans.

C. neoformans was added to microglial cultures at 4 × 105 to 6 × 105 cells per well to yield a C. neoformans-to-microglia ratio of 10:1 in the presence or absence of MAb. Cultures were washed extensively after 1.5 to 2 h of incubation at 37°C and then fed with fresh medium. After 16 h, microglial culture supernatants were collected for determination of MIP-1α and cells were fixed with methanol and then stained with Giemsa stain for the phagocytosis assay, as described previously (18).

Chemokine ELISAs.

The chemokine concentration (MIP-1α) in human microglial culture supernatants was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with kits from R&D (Minneapolis, Minn.). For some experiments, ELISA was performed with capture and detection antibody pairs from R&D. The sensitivity of detection was similar in the two ELISA systems. Microglial culture supernatants were diluted 1:5 to 1:10 before ELISA. For murine microglia, a sandwich ELISA specific for mouse MIP-1α was purchased from R&D and used as described for human chemokine determination.

Western blot analysis.

Microglia at 0.5 × 106 cells per 60-mm petri dish were incubated with C. neoformans plus MAb for the indicated time intervals, and then cells were lysed in 8 M urea. Cell lysates were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting with antibodies to extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) or phospho-ERK (pERK), both at 1:1,000 (Cell Signaling, Beverly, Mass.), or IκBα at 1:500 (New England Biolabs). The secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit-horseradish peroxidase conjugate at 1:2,000. Signals were detected by the ECL system (Amersham).

Drug treatment of microglial culture.

Specific inhibitors of ERK, U0126 and PD98059, were purchased from Promega and Calbiochem, respectively. p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase inhibitor, SB203580, was purchased from Calbiochem. All inhibitors were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC) was purchased from Sigma. Microglial cultures were treated with drugs or vehicle only for 1 h before exposure to C. neoformans plus MAb. Drugs were added back after the yeast cells were washed out. A sample of culture supernatants was tested to toxicity by the lactate dehydrogenase efflux assay, as described previously (13).

Statistics.

Means of chemokine levels and phagocytic indices in different groups were compared by analysis of variance. Relevant groups were then compared by the Student t test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

The role of Fc in MAb-opsonized C. neoformans-induced MIP-1α production.

We have previously shown that C. neoformans induces β-chemokines, MIP-1α and MIP-1β, in the presence of specific antibody (MAb 3E5 or 18B7) (18). Mouse IgG (mIgG) binds to human Fcγ receptors with different affinities. mIgG1 can bind to the low-affinity receptors, human FcγRII and FcγRIII, while mIgG2a binds to all three FcR (10, 17). mIgG2b binds to human FcγRII only and not FcγRI or FcγRIII (17, 23). Therefore, we asked whether the observed chemokine release was mediated by certain isotypes and FcR, first by exposing microglia to C. neoformans complexed to the 3E5 MAbs representing the four different isotypes (γ1, γ2a, γ2b, and γ3) (53). Both phagocytosis and MIP-1α production were determined. The results showed that exposure to MAbs bearing γ1, γ2a, and γ3, but not γ2b, induced MIP-1α production in microglia (Fig. 1). Phagocytosis was observed with all antibody isotypes except γ2b (data not shown). These results demonstrate the following: (i) chemokine induction by C. neoformans immune complex is dependent on the antibody isotype (Fc), (ii) the lack of effect of γ2b antibody bearing the same Fab as the other isotypes also demonstrates that Fc-FcR interactions and not Fab were responsible for MIP-1α production, and (iii) the lack of effect of γ2b also suggests that human FcγRII is not involved.

FIG. 1.

Effects of antibody isotypes and FcγR blocking antibody on MIP-1α production. Human microglia were exposed to C. neoformans plus MAb (3E5) bearing four different Fc fragments (γ1, γ2a, γ2b, and γ3) for 4 h, and then MIP-1α production was determined by ELISA. The results showed that MAbs bearing γ1, γ2a, and γ3, but not γ2b, induced MIP-1α production in microglia. In parallel cultures, human microglia were pretreated with Fab against human FcγRII (IV.3) or FcγRIII (3G8) for 30 min at 4°C and then incubated with C. neoformans plus MAb for an additional 16 h at 37°C. MIP-1α release was detected by ELISA. IV.3 had no effect on MIP-1α release, while 3G8 significantly inhibited MIP-1α release (P < 0.05 versus culture without blocking antibody). The experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

To determine the latter point more directly, we employed a well-characterized blocking antibody to human FcγRII (IV.3) and tested its effect on chemokine induction. The result showed that IV.3 did not inhibit MIP-1α production induced by any isotype of 3E5 (Fig. 1) or 18B7 (IgG1) (data not shown). In contrast, a blocking antibody to human FcγRIII (3G8) reduced MIP-1α release induced by all three isotypes, with its effect on γ1 and γ3 being significant (Fig. 1). Blocking antibody to human FcγRI is not available. Taken together, these results indicate that FcγRIII (and FcγRI), but not FcγRII, is involved in microglial activation.

The role of ERK MAP kinases in C. neoformans-plus-MAb-induced MIP-1α expression in microglia.

We next determined whether MAP kinases play a role in the C. neoformans-induced MIP-1α expression in microglia. Western blot analyses were performed with microglial cell lysates prepared following challenge with C. neoformans, C. neoformans plus MAb 18B7, or C. neoformans plus F(ab′)2. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at 10 ng/ml was used as a control. As shown in Fig. 2A through D, C. neoformans plus MAb induced time-dependent phosphorylation of ERK1/2. By contrast, C. neoformans plus F(ab′)2 did not induce ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, cultures treated with GXM plus MAb-opsonized C. neoformans showed induction of ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 2C). However, the amounts of pERK were reduced in cultures treated with GXM (Fig. 2C), consistent with its known inhibitory effects on chemokine expression in microglia (18). By contrast, treatment with cytochalasin D did not reduce the amounts of ERK phosphorylation but slightly delayed the kinetics (Fig. 2D). We have previously shown that cytochalasin D inhibited phagocytosis but not MIP-1α induction induced by C. neoformans plus MAb (18). Therefore, these results identify ERK activation as the best correlate of MIP-1α induction in microglia. We further examined microglia for pERK expression by specific immunostaining. To confirm that ERK plays a role in C. neoformans-plus-MAb-induced MIP-1α production, a specific pharmacological inhibitor, U0126, was tested. The results showed an inhibition of MIP-1α production by the inhibitor (Fig. 2E). Taken together, these results demonstrate a role for ERK kinases in the induction of MIP-1α by MAb-opsonized C. neoformans.

FIG. 2.

The role of ERK MAP kinases in C. neoformans-plus-MAb-induced MIP-1α expression in microglia. (A to D) Microglial cells were incubated with C. neoformans plus MAb (18B7) or F(ab′)2 at 10 μg/ml, and then Western blot analyses were performed with microglial cell lysates as described in Materials and Methods. (A) C. neoformans plus MAb induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 at approximately 10 to 30 min. Control microglia stimulated with 10 ng of LPS/ml also showed phosphorylation of ERK1/2. Microglia exposed to C. neoformans alone did not show pERK (data not shown). (B) In contrast to microglia stimulated with C. neoformans plus MAb (18B7), C. neoformans plus F(ab′)2 did not induce ERK phosphorylation. (C) Treatment with soluble polysaccharide GXM (20 μg/ml) resulted in reduction of C. neoformans-plus-MAb-induced ERK phosphorylation at 30 min. (D) In contrast, treatment with cytochalasin D (2 μM) did not inhibit ERK phosphorylation but caused a slight delay in kinetics. The blots were reprobed for total ERK to demonstrate protein loading. (E) The ERK inhibitor, U0126, reduces MIP-1α production. Microglia were pretreated with U0126 for 1 h at indicated concentrations and then incubated with C. neoformans plus MAb (18B7). MIP-1α levels were determined by ELISA after 16 h. A dose-dependent inhibition of MIP-1α production was observed with U0126. *, P < 0.05 versus C. neoformans plus 18B7. The experiments were repeated three to seven times with similar results.

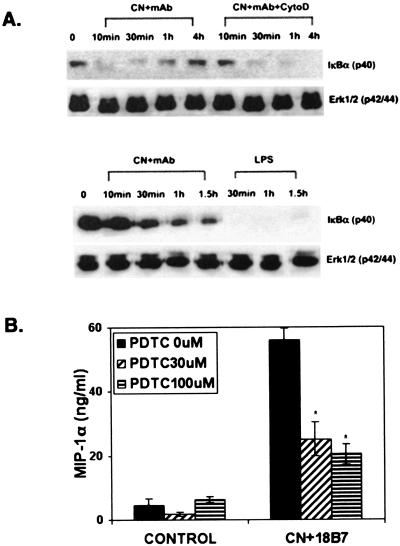

Role of NF-κB.

The transcription factor NF-κB has also been implicated in the induction of human MIP-1α gene expression (19, 51). Therefore, we determined whether NF-κB is involved in C. neoformans-plus-MAb-induced MIP-1α expression in microglia. Western blot analyses were performed with lysates from cells challenged with C. neoformans plus MAb, or LPS, to determine the amounts of IκBα. Figure 3A demonstrates time-dependent degradation of IκBα in microglial cultures challenged with C. neoformans plus MAb. LPS also induced IκBα degradation. Microglial cultures treated with C. neoformans alone did not show degradation of IκBα (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Role of NF-κB. (A) Human microglia were exposed to C. neoformans plus MAb (18B7 or 3E5) in the absence or presence of cytochalasin D at 2 μM (upper panel) or LPS at 10 ng/ml (lower panel) for the indicated time periods. Cell lysates were then subjected to Western blot analysis for IκBα expression. A time-dependent degradation of IκBα was observed in microglial cultures exposed to C. neoformans plus MAb. In cytochalasin D-treated microglia, a delay in kinetics of IκB degradation is observed. In another experiment, C. neoformans plus MAb produced IκB degradation at later time points (30 min to 1.5 h), showing a range of case variation. LPS showed more potent IκBα degradation that was sustained up to 1.5 h poststimulation. Treatment with C. neoformans alone did not alter IκBα levels (data not shown). (B) Microglia were pretreated with PDTC for 1 h at 30 and 100 μM concentrations and then incubated with C. neoformans plus MAb (18B7) as described in Materials and Methods. MIP-1α levels were determined by ELISA after 16 h. Inhibition of MIP-1α production by PDTC was observed for cultures treated with C. neoformans plus MAb. *, P < 0.05 versus experiment with no PDTC. The experiments were repeated three to five times with similar results.

IκBα degradation was also observed in cultures treated with C. neoformans plus MAb and cytochalasin D. To determine if NF-κB plays a role in the induction of C. neoformans-plus-18B7-mediated chemokine production, we tested the antioxidant NF-κB inhibitor PDTC. PDTC inhibited MIP-1α production up to 60% at a 100 μM concentration. Higher concentrations could not be tested because they produced cell toxicity (Fig. 3B). These results demonstrate that NF-κB is activated in microglia by C. neoformans plus MAb and is involved in the production of MIP-1α.

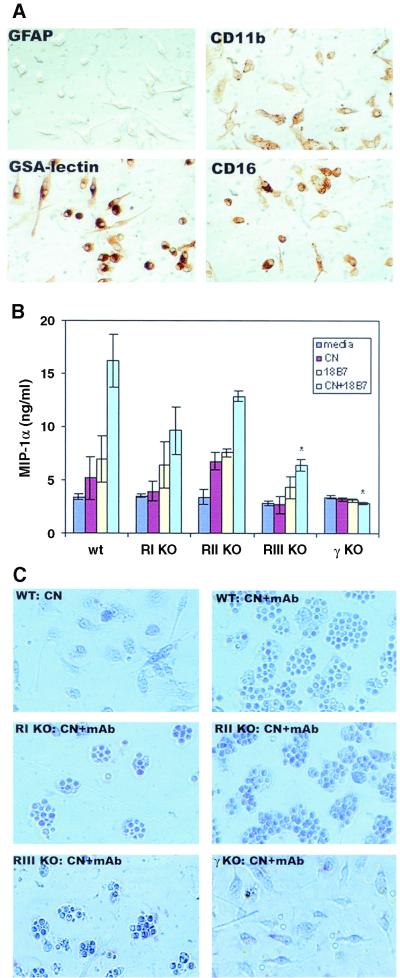

Expression of MIP-1α in microglia from FcγR-deficient mice.

To directly investigate the role of microglial FcR in MIP-1α production, we tested microglia from FcR-deficient mice. Mice used were WT mice (C57BL/6), FcγRI α-chain-deficient mice (RI KO), FcγRIII α-chain-deficient mice (RIII KO), FcγRII-deficient mice (RII KO), and common γ-chain-deficient mice (γ KO). The absence of specific gene expression was confirmed by PCR analysis of tail DNA (data not shown). Murine microglia were isolated from the neonates as previ ously described (28) (also see Materials and Methods). Microglial cells in the enriched cultures were either ameboid or ramified in shape and expressed myeloid lineage markers such as CD11b, CD16, and GSA lectin, but not GFAP (Fig. 4A ). Microglia from these mice were challenged with medium (control), C. neoformans, 18B7 (IgG1), or a combination of C. neoformans and 18B7, and then MIP-1α production was determined by ELISA, as described for human microglia. Results from these experiments showed that a combination of C. neoformans and MAb induced MIP-1α production in WT microglia, similar to human microglia (Fig. 4B). C. neoformans plus MAb also induced MIP-1α in RII KO microglia in amounts not significantly different from those in WT microglia (P > 0.05). C. neoformans plus MAb induced MIP-1α in both RI KO and RIII KO microglia (P < 0.05 versus medium or C. neoformans). However, MIP-1α production in RIII KO and not RI KO microglia was significantly less than that in WT or RII KO microglia (P < 0.05). In γ KO microglia, which are deficient in the common signaling γ chain for FcγRI and FcγRIII, induction of MIP-1α was not observed (Fig. 4B). Phagocytosis was determined by Giemsa staining, and the results showed a decrease in phagocytosis in RI KO and RIII KO microglia (Fig. 4C). In γ KO microglia, C. neoformans was attached to the surface, but no phagocytosis occurred (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these experiments demonstrate that FcγRI and FcγRIII (and their signaling γ chain) are involved in antibody-mediated MIP-1α expression as well as phagocytosis (also see the Discussion).

FIG. 4.

Expression of MIP-1α in microglia from FcγR-deficient mice. Murine microglia were isolated from the neonates of WT (wt), FcγRI α-chain-deficient (RI KO), FcγRIII α-chain-deficient (RIII KO), FcγRII-deficient (RII KO), and the common γ-chain-deficient (γ KO) mice as described in the text. (A) Murine microglial cells in enriched cultures were examined for the expression of CD11b, CD16, GSA lectin, and GFAP by immunohistocytochemistry as described in Materials and Methods. Mouse microglia express CD11b (CR3), CD16 (FcγRIII), and GSA lectin. Cultures were highly pure as demonstrated by lack of astrocytes (GFAP+). (B) Murine microglia were exposed to medium only (media), C. neoformans, MAb (18B7), or C. neoformans plus 18B7, as described for human microglia experiments. ELISA specific for murine MIP-1α was used to determine chemokine levels. Each data point represents three to six wells (mean ± standard deviation). All except γ KO mouse microglia showed induction of MIP-1α after exposure to C. neoformans plus 18B7. RIII KO microglia produced significantly less MIP-1α than did WT microglia. *, P < 0.05 versus WT. (C) Giemsa staining of the WT microglia showed that C. neoformans phagocytosis occurred in the presence of specific antibody 18B7. A decrease in phagocytosis of 18B7-opsonized C. neoformans was observed in RI KO and RIII KO microglia but not in RII KO microglia. In γ KO microglia, C. neoformans cells were attached to the surface, but no phagocytosis occurred. The results are representative of five independent experiments with similar results.

DISCUSSION

The results of our study demonstrate that FcR-dependent pathways are involved in MIP-1α expression by MAb-opsonized C. neoformans immune complexes. Complexes with mouse MAb of IgG2b isotype had no stimulatory effect on human microglia, while other isotypes did. These results indicate that microglial chemokine induction (as well as phagocytosis) was dependent on Fc and FcR but that FcRII was not involved.

The three types of Fcγ receptors bind mIgG of different isotypes with different affinities (10, 17, 43). Human FcγRI binds mIgG2a and mIgG3 with high affinity, but it does not bind mIgG2b. In contrast, murine FcγRII and FcγRIII bind mIgG1, mIgG2a, and mIgG2b with approximately the same affinity. Consistent with this hierarchy, IgG2b failed to induce phagocytosis or MIP-1α production in human microglia, while all four IgGs (IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3) induced phagocytosis in murine microglia (data not shown). Murine and human FcR also differ significantly with respect to the subunit composition and function. For instance, human FcγRII consists of at least two different isoforms, IIa and IIb, bearing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif, respectively. In contrast, murine FcγRII consists of only IIb, bearing the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif, consistent with the notion that murine FcγII does not transmit the activation signal. Accordingly, our results showed that, in murine FcγRII-deficient microglia, C. neoformans immune complexes induced phagocytosis and MIP-1α production as in WT microglia. Furthermore, in human microglia, MAb IV.3, which is directed against the Fc-binding domain of FcγRIIa, did not inhibit phagocytosis or MIP-1α production, indicating that the ITAM-bearing FcγRII did not participate in human microglial activation. These data point to the role of FcγRI and FcγRIII in microglial MIP-1α induction.

Our results with FcR-deficient microglia provide direct evidence that FcγRI and FcγRIII mediated phagocytic and MIP-1α-inducing signals in microglia. FcγRI and FcγRIII are composed of different Fc-binding α-chains and share a common signaling γ-chain with the ITAM motif. In γ-chain-deficient microglia, neither phagocytosis nor MIP-1α production was observed. In contrast, in FcγRI- or FcγRIII α-chain-deficient microglia, phagocytosis and MIP-1α production were diminished but not completely inhibited.

Our results are somewhat unexpected, given that we used 18B7 (IgG1) as an opsonin and that mIgG1 is not known to bind to FcR of either human or murine origin with high affinity (10, 17, 43). For instance, previously we showed that immobilized IgG2a was more efficient than IgG1 in activating human microglia (18), and yet, when administered as a C. neoformans immune complex, IgG1 (3E5) was more efficient than IgG2a in activating microglia (Fig. 1). Furthermore, unlike the reports in which phagocytosis of IgG1 immune complex was abolished in RIII KO and unchanged in RI KO cells (15), we see partial inhibition of MIP-1α release in both RIII KO and RI KO microglia, although only inhibition in RIII KO cells was significant. Furthermore, significant MIP-1α release was observed in RIII KO microglia in response to C. neoformans plus 18B7, which is attributable to RI. These results suggest that, in addition to classical Fc-FcR interactions, other antibody-mediated activation pathways are probably elicited by C. neoformans plus 18B7.

FcR signal through ITAM motifs that connect the ligand-binding module with intracellular effectors of signal transduction pathways (10, 17, 24). Tyrosine kinases of the src and syk family play crucial roles in signaling through the immunoreceptors (48). In addition, MAP kinases are activated following FcR engagement (9). Our results strongly point to the role of ERK MAP kinase in MIP-1α expression in microglia induced by C. neoformans and MAb. Robust ERK phosphorylation and immunoreactivity for pERK were observed following exposure to C. neoformans plus MAb, and specific ERK inhibitors suppressed MIP-1α production from microglia. Furthermore, the conditions that led to inhibition of MIP-1α expression, such as exposure to soluble GXM (18), also led to inhibition of ERK phosphorylation, while those that did not inhibit MIP-1α production (such as cytochalasin D) (18) did not. Since tyrosine kinases are involved in both ITAM and MAP kinase signaling, our previous results demonstrating an inhibitory effect of herbimycin A (18) are also consistent with their role in microglial activation.

The transcription factor NF-κB is normally held inactive in the cytosol by association with IκB. Upon receiving the activating signals, IκB is phosphorylated and ubiquitinated and then degraded in the proteosome (34, 36). The freed NF-κB then translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to the promoter region of the genes that bear specific binding sites. Degradation of IκB signals for the new synthesis of IκB via increased transcription. Therefore, the demonstration of transient degradation of total IκB is a marker for activation of NF-κB. Subsequent to incubation with MAb-opsonized C. neoformans, microglial cells showed time-dependent IκB degradation, which returned to normal levels by 4 h. In addition, the antioxidant inhibitor of NF-κB, PDTC, inhibited MIP-1α production. These results demonstrate that NF-κB activation occurs in microglia following stimulation with MAb-opsonized C. neoformans and that it is involved in immune-complex-induced chemokine production. Indeed, activation of NF-κB and ERK kinases has been demonstrated for THP-1 monocytic cell lines following exposure to immune complexes (45), and MAP kinase-MAP kinase kinase kinase have been shown elsewhere to activate the IκB kinase complex, which is responsible for phosphorylation of IκBα (25). Our results, however, do not support such a scenario, because the ERK inhibitors failed to suppress NF-κB activation in primary microglial cells by a number of stimuli including immune complexes (data not shown). ERK kinases most likely affected MIP-1α expression by inducing AP-1 transcription factors and targeting AP-1-sensitive sites in the promoter or by interacting with cellular activation pathways other than NF-κB.

The proximal promoters of the MIP-1α and MIP-1β genes exhibit consensus sequences for NF-κB, C/EBP, and ATF/CBP, which confer cell-specific and inducible expression of these chemokines (19, 41). Consistent with this, our data show that MIP-1α production by opsonized C. neoformans in microglia was dependent on NF-κB. Interestingly, cytochalasin D, a stimulus that effectively suppressed phagocytosis but not MIP-1α expression (18), did not inhibit NF-κB activation, an observation also made for THP-1 cells (16). The prototype activators of NF-κB, such as bacterial endotoxin, IL-1, or tumor necrosis factor alpha, are good inducers of the MIP-1α gene (22, 35a), and in addition, we also found that an antiviral cytokine, beta interferon (IFN-β), mediates β-chemokine gene induction in microglia via NF-κB (26a). Together, these results support NF-κB as a signaling component activated by the immune complex and support the idea that activation of this transcription factor is a global requirement for the chemokine gene expression in microglia.

In summary, we partially delineated the novel pathway through which immune complexes activate microglial cells. We further demonstrated some of the signaling components downstream of FcR activation in microglia. The results of this study have wide implications for CNS disorders in which microglial FcR signaling may play a role in pathogenesis or in therapy. These include infectious, inflammatory, and degenerative diseases such as C. neoformans meningoencephalitis, multiple sclerosis, and Alzheimer's disease (1, 3, 5, 37). FcRI and FcRIII are expressed in human microglia in vivo in both healthy and diseased brains (40, 49), and their expression in macrophages is regulated by proinflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ (50). Therefore, the macrophage-activating effects of FcR signaling could be further amplified in inflammatory brain diseases. In patients with AIDS dementia, the number of circulating CD16 (FcγRIII)-positive monocytes is significantly elevated (42). Although a direct link between FcR and HIV infection has not been established, these data suggest that this subset of monocytes could carry HIV-1 to the brain. Activation of FcR by MAb 2H1-coated C. neoformans has been shown previously to induce HIV expression in monocytic cells, suggesting a mechanism by which immune complexes can promote viral infection (20). Our demonstration of microglial cell FcR signaling through NF-κB and ERK MAP kinase also suggests that a number of other macrophage genes are likely to be activated following FcR cross-linking as well. These include cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, and growth factors, the expression of which will profoundly alter the neural environment and the course of the diseases. Our study also suggests that 18B7, which is in clinical trials, can promote not only phagocytosis and fungistasis but also CNS chemokine production, to help overcome the apparent lack of inflammation associated with the unfavorable clinical outcome (29, 30). The exact nature of the FcR-mediated responses in vivo remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Einstein Human Fetal Tissue Repository for tissue and Wa Shen for preparation of the human microglial cultures.

This study was supported by grants AI44641 and MH55477 to S.C.L. and AI43937 to M.S. S.S. was supported by NIH training grants T32, GM07288, and AI07506.

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Bard, F., C. Cannon, R. Barbour, R. L. Burke, D. Games, H. Grajeda, T. Guido, K. Hu, J. Huang, K. Johnson-Wood, K. Khan, D. Kholodenko, M. Lee, I. Lieberburg, R. Motter, M. Nguyen, F. Soriano, N. Vasquez, K. Weiss, B. Welch, P. Seubert, D. Schenk, and T. Yednock. 2000. Peripherally administered antibodies against amyloid beta-peptide enter the central nervous system and reduce pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Nat. Med. 6:916-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger, E. A., P. M. Murphy, and J. M. Farber. 1999. Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism, and disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17:657-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brazil, M. I., H. Chung, and F. R. Maxfield. 2000. Effects of incorporation of immunoglobulin G and complement component C1q on uptake and degradation of Alzheimer's disease amyloid fibrils by microglia. J. Biol. Chem. 275:16941-16947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casadevall, A., M. Deshaw, M. Fan, F. Dromer, T. R. Kozel, and L. A. Pirofski. 1994. Molecular and idiotypic analysis of antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan. Infect. Immun. 62:3864-3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casadevall, A., D. Goldman, and S. C. Lee. 2000. Cryptococcal meningoencephalitis. In P. K. Peterson and J. S. Remington (ed.), New concepts on the immunopathogenesis of CNS infections. Blackwell Science, Inc., Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 6.Casadevall, A., and J. R. Perfect. 1998. Human cryptococcosis, p. 407-456. In A. Casadevall and J. R. Perfect (ed.), Cryptococcus neoformans. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 7.Casadevall, A., and M. D. Scharff. 1991. The mouse antibody response to infection with Cryptococcus neoformans: VH and VL usage in polysaccharide binding antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 174:151-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chuck, S. L., and M. A. Sande. 1989. Infections with Cryptococcus neoformans in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 321:794-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coxon, P. Y., M. J. Rane, D. W. Powell, J. B. Klein, and K. R. McLeish. 2000. Differential mitogen-activated protein kinase stimulation by Fc-gamma receptor IIa and IIIb determines the activation phenotype of human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 164:6530-6537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daeron, M. 1997. Fc receptor biology. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:203-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diamond, R. D. 1990. Cryptococcosis neoformans, p. 1980-1989. In G. L. Mandell, R. G. Douglas, Jr., and J. E. Bennett (ed.), Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone, New York, N.Y.

- 12.Dong, Z. M., and J. W. Murphy. 1995. Intravascular cryptococcal culture filtrate (CneF) and its major component, glucuronoxylomannan, are potent inhibitors of leukocyte accumulation. Infect. Immun. 63:770-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downen, M., T. D. Amaral, L. L. Hua, M. L. Zhao, and S. C. Lee. 1999. Neuronal death in cytokine-activated primary human brain cell culture: role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Glia 28:114-127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duque, N., C. Gomez-Guerrero, and J. Egido. 1997. Interaction of IgA with Fc alpha receptors of human mesangial cells activates transcription factor nuclear factor-kappa B and induces expression and synthesis of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, IL-8 and IFN-inducible protein 10. J. Immunol. 159:3474-3482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fossati-Jimack, L., A. Ioan-Facsinay, L. Reininger, Y. Chicheportiche, N. Watanabe, T. Saito, F. M. Hofhuis, J. E. Gessner, C. Schiller, R. E. Schmidt, T. Honjo, J. S. Verbeek, and S. Izui. 2000. Markedly different pathogenicity of four immunoglobulin G isotype-switch variants of an antierythrocyte autoantibody is based on their capacity to interact in vivo with the low-affinity Fcγ receptor III. J. Exp. Med. 191:1293-1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Garcia, E., G. Sanchez-Mejorada, and C. Rosales. 2001. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and ERK are required for NF-κB activation but not for phagocytosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 70:649-658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gessner, J. E., H. Heiken, A. Tamm, and R. E. Schmidt. 1998. The IgG Fc receptor family. Ann. Hematol. 76:231-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldman, D., X. Song, R. Kitai, A. Casadevall, M. L. Zhao, and S. C. Lee. 2001. Cryptococcus neoformans induces macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α) and MIP-1β in human microglia: role of specific antibody and soluble capsular polysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 69:1808-1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grove, M., and M. Plumb. 1993. C/EBP, NF-κB, and c-Ets family members and transcriptional regulation of the cell-specific and inducible macrophage inflammatory protein 1α immediate-early gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:5276-5289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison, T. S., S.-H. Nong, and S. M. Levitz. 1997. Induction of human immunodeficiency virus type I expression in monocytic cells by Cryptococcus neoformans and Candida albicans. J. Infect. Dis. 176:485-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffman, T. L., and R. W. Doms. 1998. Chemokines and coreceptors in HIV/SIV host interactions. AIDS 12:S17-S26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hua, L. L., and S. C. Lee. 2000. Distinct patterns of stimulus-inducible chemokine mRNA accumulation in human fetal astrocytes and microglia. Glia 30:74-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hulett, M. D., and P. M. Hogarth. 1994. Molecular basis of Fc receptor function. Adv. Immunol. 57:1-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isakov, N. 1997. Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM), a unique module linking antigen and Fc receptors to their signaling cascades. J. Leukoc. Biol. 61:6-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joyce, D., C. Albanese, J. Steer, M. Fu, B. Bouzahzah, and R. G. Pestell. 2001. NF-κB and cell-cycle regulation: the cyclin connection. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 12:73-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessel, J. M., J. Hayflick, A. S. Weyrich, P. A. Hoffman, M. Gallatin, T. M. McIntyre, S. M. Prescott, and G. A. Zimmerman. 1998. Coengagement of ICAM-3 and Fc receptors induces chemokine secretion and spreading of myeloid leukocytes. J. Immunol. 160:5579-5587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26a.Kim, M. O., Q. Si, J. N. Zhou, R. G. Pestell, C. F. Brosnan, J. Locker, and S. C. Lee. 2002. Interferon-beta activates multiple signaling cascades in primary human microglia. J. Neurochem. 81:1361-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozel, T. R., W. F. Gulley, and J. Cazin. 1977. Immune response to Cryptococcus neoformans soluble polysaccharide: immunological unresponsiveness. Infect. Immun. 18:701-707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, S. C., M. Collins, P. Vanguri, and M. L. Shin. 1992. Glutamate differentially inhibits the expression of class II MHC antigens on astrocytes and microglia. J. Immunol. 148:3391-3397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, S. C., D. W. Dickson, and A. Casadevall. 1996. Pathology of cryptococcal meningoencephalitis: analysis of 27 patients with pathogenetic implications. Hum. Pathol. 27:839-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee, S. C., Y. Kress, D. W. Dickson, and A. Casadevall. 1995. Human microglia mediate anti-Cryptococcus neoformans activity in the presence of specific antibody. J. Neuroimmunol. 62:43-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, S. C., Y. Kress, M.-L. Zhao, D. W. Dickson, and A. Casadevall. 1995. Cryptococcus neoformans survive and replicate in human microglia. Lab. Investig. 73:871-879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee, S. C., W. Liu, C. F. Brosnan, and D. W. Dickson. 1992. Characterization of human fetal dissociated CNS cultures with an emphasis on microglia. Lab. Investig. 67:465-475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luster, A. D. 1998. Chemokines—chemotactic cytokines in inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 338:436-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.May, M. J., and S. Ghosh. 1998. Signal transduction through NF-κB. Immunol. Today 19:80-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McManus, C., J. S. H. Liu, M. Hahn, L. L. Hua, C. F. Brosnan, J. W. Berman, and S. C. Lee. 2000. Differential induction of β-chemokines by type I and type II interferons in human microglia. Glia 29:273-280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35a.McManus, C. M., C. F. Brosnan, and J. W. Berman. 1998. Cytokine induction of MIP-1 alpha and MIP-1 beta in human fetal microglia. J. Immunol. 160:1449-1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mercurio, F., and A. M. Manning. 1999. Multiple signals converging on NF-κB. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11:226-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore, G. R., and C. S. Raine. 1988. Immunogold localization and analysis of IgG during immune-mediated demyelination. Lab. Investig. 59:641-648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mukherjee, J., A. Casadevall, and M. D. Scharff. 1993. Molecular characterization of the antibody responses to Cryptococcus neoformans infection and glucuronoxylomannan-tetanus toxoid conjugate immunization. J. Exp. Med. 177:1105-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy, J. W., and G. C. Cozad. 1972. Immunological unresponsiveness induced by cryptococcal polysaccharide assayed by the hemolytic plaque technique. Infect. Immun. 5:896-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peress, N. S., H. B. Fleit, E. Perillo, R. Kuljis, and C. Pezzallo. 1993. Identification of Fc gamma RI, II and III on normal human brain ramified microglia and on microglia in senile plaques in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neuroimmunol. 48:71-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Proffitt, J., G. Crabtree, M. Grove, P. Daubersies, B. Bailleul, E. Wright, and M. Plumb. 1995. An ATF/CREB-binding site is essential for cell-specific and inducible transcription of the murine MIP-1β cytokine gene. Gene 152:173-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pulliam, L., R. Gascon, M. Stubblebine, D. McGuire, and M. S. McGrath. 1997. Unique monocyte subset in patients with AIDS dementia. Lancet 349:692-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ravetch, J. V. 1997. Fc receptors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 9:121-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rollins, B. J. 1997. Chemokines. Blood 90:909-928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanchez-Mejorada, G., and C. Rosales. 1998. Fcγ receptor-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in monocytes is independent of Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 273:27610-27619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schall, T. J., and K. B. Bacon. 1994. Chemokines, leukocyte trafficking, and inflammation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 6:865-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steenbergen, J., and A. Casadevall. 2000. Prevalence of Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans (serotype D) and Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii (serotype A) isolates in New York City. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1974-1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turner, M., E. Schweighoffer, F. Colucci, J. P. Di Santo, and V. L. Tybulewicz. 2000. Tyrosine kinase SYK: essential functions for immunoreceptor signalling. Immunol. Today 21:148-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ulvestad, E., K. Williams, C. Vedeler, J. Antel, H. Nyland, S. Mork, and R. Matre. 1994. Reactive microglia in multiple sclerosis lesions have an increased expression of receptors for the Fc part of IgG. J. Neurol. Sci. 121:125-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weyenbergh, J. V., P. Lipinski, A. Abadie, D. Chabas, U. Blank, R. Liblau, and J. Wietzerbin. 1998. Antagonistic action of IFN-β and IFN-γ on high affinity Fc-γ receptor expression in healthy controls and multiple sclerosis patients. J. Immunol. 161:1568-1574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Widmer, U., K. R. Manogue, A. Cerami, and B. Sherry. 1993. Genomic cloning and promoter analysis of macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-2, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β, members of the chemokine superfamily of proinflammatory cytokines. J. Immunol. 150:4996-5012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yano, K., M. Yamaguchi, F. de Mora, C. S. Lantz, J. H. Butterfield, J. J. Costa, and S. J. Galli. 1997. Production of macrophage inflammatory protein-1α by human mast cells: increased anti-IgE-dependent secretion after IgE-dependent enhancement of mast cell IgE-binding ability. Lab. Investig. 77:185-193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuan, R. R., G. Spira, J. Oh, M. Paizi, A. Casadevall, and M. D. Scharff. 1998. Isotype switching increases efficacy of antibody protection against Cryptococcus neoformans infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 66:1057-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]