Abstract

In order to plan for the wide-scale introduction of meningococcal C conjugate (MCC) vaccine for United Kingdom children up to 18 years old, phase II trials were undertaken to investigate whether there was any interaction between MCC vaccines conjugated to tetanus toxoid (TT) or a derivative of diphtheria toxin (CRM197) and diphtheria-tetanus vaccines given for boosting at school entry or leaving. Children (n = 1,766) received a diphtheria-tetanus booster either 1 month before, 1 month after, or concurrently with one of three MCC vaccines conjugated to CRM197 or TT. All of the MCC vaccines induced high antibody responses to the serogroup C polysaccharide that were indicative of protection. The immune response to the MCC-TT vaccine was reduced as a result of prior immunization with a tetanus-containing vaccine, but antibody levels were still well above the lower threshold for protection. Prior or simultaneous administration of a diphtheria-containing vaccine did not affect the response to MCC-CRM197 vaccines. The immune responses to the carrier proteins were similar to those induced by a comparable dose of diphtheria or tetanus vaccine. The results also demonstrate that, for these conjugate vaccines in these age groups, both standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and those that measure high-avidity antibodies to meningococcal C polysaccharide correlated equally well with assays that measure serum bactericidal antibodies, the established serological correlate of protection for MCC vaccines.

In November 1999, the United Kingdom introduced conjugate vaccines against meningococcal serogroup C disease (MCC vaccines) into its immunization schedule for infants, with promising early reports of efficacy (18). The vaccines were also offered to all children between 1 and 17 years of age as a catch-up program that started in November 1999 and was completed within a year. The evidence of safety and immunogenicity of the MCC vaccines in these age groups was obtained from phase II trials conducted in the United Kingdom and sponsored by the Department of Health. Following promising results of early trials using the 2-, 3-, and 4-month schedule in United Kingdom infants (16), the Department of Health sponsored a comprehensive clinical trials program to evaluate the performance of candidate MCC vaccines in toddlers, children starting school, children leaving school, and young adults (12).

One concern was the potential for interaction between the MCC vaccines, which contained either tetanus toxoid (TT) or the CRM197 derivative of diphtheria toxin as the protein carrier, and the diphtheria and tetanus vaccines given as booster doses at school entry (DT) or school leaving (Td). To address these concerns, trials were conducted in which children received MCC vaccine a month before or after, or at the same time as, their DT or Td booster vaccine. Humoral immune responses against DT and MCC antigens were assessed following each vaccination.

Since it was anticipated that licensure of the MCC vaccines would be based on immunogenicity data alone, without direct evidence of efficacy, considerable attention was given in the clinical trials program to the development and validation of the assays that would provide the serological correlates of protection (2). Earlier studies on meningococcal disease had established that the presence of specific serum bactericidal antibody was a correlate of protection (7). However, although they are now standardized (5, 11), these assays are time-consuming and involve the use of live pathogens. Attempts have therefore been made to replace the functional serum bactericidal antibody assay (SBA) with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay(s) (ELISA) that correlates strongly with the SBA. There is some evidence that ELISAs that measure only high-avidity antibodies correlate better with SBAs than standard ELISAs that measure total immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels against the polysaccharide (8). However, those studies were undertaken using responses generated in young children with plain meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine, and this may not apply when IgG responses to conjugated vaccines are measured.

Assays for immune responses against meningococcal C polysaccharide are further complicated by the natural occurrence of two forms of the capsule, depending on the presence or not of an O-acetyl group on the C-7 or C-8 residue of the constituent neuraminic acid molecules. Meningococcal strains that possess capsules that are O acetylated (OAc+) currently predominate in the United Kingdom over strains with capsules that are de-O acetylated (OAc−) (3). MCC vaccines from different manufacturers vary in the use of OAc+ or OAc− forms in their formulation, and this may have an impact on the immune response against meningococcal strains bearing the homologous or heterologous form of the capsule (4).

There are therefore four types of ELISA that could be used to determine the antibody response to MCC vaccines: standard IgG ELISAs and high-avidity ELISAs using either OAc+ or OAc− polysaccharides. The phase II trials to investigate the interaction between MCC and DT or Td vaccines provided an opportunity to assess the correlation of these different ELISAs with SBA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and vaccination schedule.

The study population comprised children in North Hertfordshire or Gloucestershire, England, who were eligible to receive their school entry DT booster at between 3.5 and 6 years of age or their school leaving booster at between 13 and 18 years. Only children who had received the recommended number of doses of diphtheria-tetanus-containing vaccines for their age group were included, namely, three for the school entry cohort and four for the school leaver cohort. Minimums of 3 years since the last DT-containing vaccine for school starters and 2 years for school leavers were specified. Children who had received another vaccine within the previous 3 months were excluded. Children were randomized to receive DT or Td vaccine 1 month before (group 1), 1 month after (group 2), or concurrently with (group 3) one of three MCC vaccines. Randomization to the nine vaccine schedule groups was by a computerized block procedure with a block size of 90. A second dose of MCC vaccine was offered to any study participant considered not to have evidence of an antibody response (see below).

Written informed consent was obtained for all participants in the trials, from the subjects and/or their parents or guardians where appropriate. The trials were conducted according to International Committee for Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and with appropriate quality assurance. Ethical approval was obtained from the Public Health Laboratory Service and appropriate local research ethics committees.

Vaccines.

The MCC vaccines were provided by three manufacturers: Wyeth Lederle Vaccines, Pearl River, N.Y.; Chiron Vaccines, Siena, Italy; and Baxter Hyland Immuno (formerly North American Vaccines Inc.), Beltsville, Md. The Wyeth vaccine contained 8 to 12 μg of meningococcal C OAc+ oligosaccharide conjugated to 8 to 12 μg of CRM197 per dose in aluminum phosphate gel. The Chiron vaccine contained 12 μg of OAc+ oligosaccharide conjugated to 30 μg of CRM197 per dose added to aluminum hydroxide gel. The Baxter vaccine contained 10 μg of sized OAc− polysaccharide conjugated to 20 μg of TT in aluminum hydroxide gel.

The DT and Td vaccines were supplied by the United Kingdom Department of Health from batches in routine use in the United Kingdom (Aventis Pasteur MSD). The DT and Td vaccines had a tetanus potency of not less than 40 IU/dose; the diphtheria potency of the DT vaccine was not less than 30 IU/dose, and that of the Td vaccine was not less than 4 IU/dose. The DT vaccine had diphtheria and tetanus antigen contents of approximately 25 and 10 limits of flocculation (Lf) per dose, respectively. For the Td vaccine the corresponding values were approximately 2 to 3 Lf of diphtheria toxoid and 10 Lf of TT. For D vaccines, 1 Lf usually approximates very roughly 4 to 5 μg of protein, so the CRM vaccines are equivalent to between one and three doses of a conventional low-dose vaccine. Both the DT and Td vaccines were adsorbed onto aluminum hydroxide.

Due to delay in supply of the Baxter vaccine for the school leaver cohort, this trial began with only two vaccines, with inclusion of the Baxter vaccine 10 months later. Rerandomization to maintain a 1:1:1 ratio between the three manufacturers was undertaken at this point. Wyeth-Lederle withdrew its vaccine from both trials in October 1999 before completion of the targeted trial numbers upon issue of a product license in the United Kingdom. A second rerandomization was therefore undertaken to ensure a 1:1 ratio between the remaining two vaccines.

The MCC vaccines were administered by intramuscular injection into the right arm, and the Td and DT vaccines were administered into the left arm.

Blood samples.

Individuals were bled 4 weeks after each immunization for assessment of antibodies to meningococcal C polysaccharide, diphtheria, and tetanus. The schedule for vaccination and blood sampling is shown in Table 1. Sera were separated and ELISAs were performed at the Centre for Applied Microbiology and Research (CAMR), United Kingdom. Aliquots of separated sera were sent, in dry ice, to the PHLS Meningococcal Reference Unit, Manchester, United Kingdom, for SBA.

TABLE 1.

Treatment schedules for nine groups defined by vaccination schedule and timing of MCC administration vaccine

| Group (vaccination)a | Action taken at:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time zero | 4-6 wk | 8-12 wk | |

| 1 (DT or Td, then MCC) | DT or Td administered | Blood taken, then MCC administered | Blood taken |

| 2 (MCC, then DT or Td) | MCC administered | Blood taken, then DT or Td administered | Blood taken |

| 3 (MCC with DT or Td) | Blood taken then MCC plus DT or Td administered | Blood taken | |

MCC, one of three MCC vaccines: Chiron (CRM), Wyeth (CRM), or Baxter (TT). DT was given to preschool children, and Td was given to school leavers.

For individuals for whom a second dose of MCC vaccine was recommended, an MCC antibody test was offered at 4 weeks after revaccination.

Antibody assays.

All sera were assayed blindly for IgG antibody by the standard ELISA with OAc+ polysaccharide as previously described (5). In addition, a subset of sera comprising approximately 20% of the total within each age group in order of receipt at CAMR were assayed by the standard ELISA with OAc− polysaccharide, by the high-avidity ELISA with OAc+ antigen, and by SBA. The antigen for the ELISAs comprised either naturally (not chemically derived) OAc− (CAMR) or OAc+ (Aventis Pasteur, Lyon, France) serogroup C polysaccharide. The high-avidity ELISA was a modification of the standard ELISA incorporating 75 mM ammonium thiocyanate in the serum diluent as described by Granoff et al. (8). Apart from the addition of thiocyanate to the serum diluent, the only other deviation from the standardized ELISA methodology was the use of 0.05% Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, Dorset, United Kingdom) in place of 0.1% Brij 35. The calibration factor of the standard CDC1992 serum for serogroup C-specific IgG used in both OAc− and OAc+ assays was 24.1 μg/ml for the standard assay (10) and 19.6 arbitrary units (AU) of high-avidity antibody per ml (D. Granoff, personal communication). SBAs were performed as described by Maslanka et al. (11) with baby rabbit serum (Pel-Freeze Inc., Rodgerson, Ariz.) as an exogenous complement source (referred to as rSBA in this paper). The target strain used throughout was C11 (C:16:P1.7a,1, OAc+ strain). Serum bactericidal antibody titers were expressed as the reciprocal of the final serum dilution giving ≥50% killing after 60 min.

For the purposes of advising on the need for revaccination, evidence of an antibody response to MCC vaccine was defined as follows: postvaccination rSBA titer of ≥8 or, for those with no rSBA result, a fourfold rise in OAc+ IgG concentration from pre- to post-MCC and with a post-MCC level of >2 μg/ml. Since children in group 2 did not have a pre-MCC vaccination sample taken (Table 1), all adequate post-MCC samples in this group were tested by rSBA. The criteria used in this study to decide on revaccination were evaluated against the established correlates of protection based on rSBA responses (2).

For diphtheria and tetanus ELISAs, standard procedures were employed (9, 15). Plates were coated with Evans Vaccines diphtheria toxoid and TT at 0.5 Lf/ml. After incubation and washing, wells were blocked with 50 μl of phosphate-buffered saline-0.1% Tween-10% fetal calf serum. Samples, standards (first International Standard for Anti-Tetanus Ig; human TE-3 and diphtheria antitoxic human serum, 91/534, both at 1 IU/ml), and in-house controls were diluted threefold on separate plates. and 50 μl was transferred to the coated plates, to give a final starting dilution of 1/100. After incubation, 100 μl of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated mouse monoclonal anti-human IgG Fc PAN (clone HP6043) was added to all wells, and the plates incubated, washed, and developed with the substrate 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine dihydrochloride (TMB).

For a small subset of sera, diphtheria antitoxin levels were also measured at the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control in the in vitro Vero cell toxin neutralization assay (14).

Statistical methods.

Antibody levels were log transformed. and geometric means with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Comparisons between schedules, between vaccines, and between school starters and leavers as well as between males and females were performed by using normal errors regression. Differences between groups were taken to be statistically significant at a 0.5% significance level rather than the traditional 5% level in order to make an allowance for the large number of possible comparisons. Furthermore, two groups of similar size and with similar variance whose 95% CIs do not overlap will be significant at approximately a 0.5% level. This enables significant differences between groups to be assessed by nonoverlapping CIs. Correlation between assays was calculated by using rank correlation, and 95% CIs on the correlations were obtained by using bootstrapping.

RESULTS

Compliance with sampling.

A total of 843 children were recruited in the school entry cohort (mean age, 4.3 years; range, 3.5 to 5.9 years) between January 1998 and May 2000, and 923 were recruited in the school leaver cohort (mean age, 15.1 years; range, 14.1 to 17.8 years) between May 1998 and January 2000. Of these, 832 (98.7%) and 917 (99.3%), respectively, received both study vaccines; 11 children in the school entry cohort and 6 in the school leaver cohort failed to complete their vaccination schedule due to movement away from the study area or parental withdrawal.

Adequate post-MCC blood samples were obtained from 700 children (84.1.% of those completing their immunization schedule) in the school entry cohort and 893 (97.3%) in the school leaver cohort; of these 156 (22.3%) and 171 (19.1%), respectively, were tested by all four assays. The number of sera tested by all four assays in the Baxter-TT vaccine group was less due to late inclusion of this vaccine in the trial.

Antibody responses to MCC vaccines.

For all MCC assays, responses in the school leaver cohort were, on average, between 1.7- and 3.7-fold higher than those in the school entry cohort, depending on the assay used and whether the sample was taken pre- or postvaccination. However, since the differences were consistent between vaccines and schedules, the results for the school entry and school leaver cohorts have been combined across vaccines and schedules for some analyses. There were no differences in the levels of response between males and females for any of the MCC assays.

(i) ELISA.

When assayed by the OAc+ ELISA, the Baxter MCC-TT and Wyeth MCC-CRM vaccines gave the highest geometric mean concentrations (GMCs) in groups 2 and 3, but only the Wyeth MCC-CRM was highest in group 1, where DT or Td was given prior to MCC vaccine (Table 2). Both with the OAc+ ELISA and in the 20% subset tested by the OAc− ELISA, prior administration of DT or Td significantly reduced the GMC to Baxter-TT vaccine but not those to the two CRM conjugate MCC vaccines.

TABLE 2.

Meningococcal serogroup C responses 1 month after meningococcal conjugate vaccinea

| Group (vaccination) | Vaccine | OAc+ ELISA

|

OAc− ELISA

|

OAc+ avidity ELISA

|

rSBA

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. tested | GMC (95% CI) | No. tested | GMC (95% CI) | No. tested | GMC (95% CI) | No. tested | GMT (95% CI) | ||

| 1 (DT or Td, then MCC) | Chiron MCC-CRM | 199 | 14.8 (12.2-18.0) | 54 | 12.10 (9.23-15.85) | 55 | 7.73 (5.63-10.62) | 62 | 740 (454-1,207) |

| Wyeth MCC-CRM | 134 | 23.8 (18.3-30.9) | 54 | 17.33 (12.46-24.12) | 52 | 10.56 (7.02-15.88) | 58 | 2,048 (1,367-3,067) | |

| Baxter MCC-TT | 198 | 10.7 (8.9-12.9) | 36 | 17.39 (10.87-27.81) | 35 | 4.16 (2.37-7.29) | 31 | 1,400 (763-2,569) | |

| 2 (MCC, then DT or Td) | Chiron MCC-CRM | 175 | 14.7 (11.4-18.9) | 46 | 20.07 (12.61-31.93) | 50 | 10.10 (5.53-18.44) | 51 | 1,142 (655-1,990) |

| Wyeth MCC-CRM | 157 | 23.7 (18.3-30.6) | 49 | 19.66 (12.99-29.77) | 48 | 13.28 (7.68-22.96) | 55 | 1,898 (1,089-3,311) | |

| Baxter MCC-TT | 178 | 29.1 (24.3-34.9) | 32 | 51.56 (32.8-81.0) | 38 | 15.39 (9.81-24.13) | 28 | 4,412 (3,003-6,482) | |

| 3 (MCC with DT or Td) | Chiron MCC-CRM | 196 | 12.1 (9.5-15.3) | 55 | 16.13 (10.31-25.57) | 53 | 10.87 (6.50-18.19) | 63 | 877 (515-1,494) |

| Wyeth MCC-CRM | 163 | 20.1 (15.7-25.6) | 48 | 18.71 (12.54-27.90) | 45 | 13.66 (8.74-21.35) | 56 | 1,638 (991-2,710) | |

| Baxter MCC-TT | 193 | 23.8 (19.3-29.4) | 41 | 31.99 (23.05-44.41) | 43 | 7.88 (5.07-12.26) | 41 | 2,191 (1,342-3,577) | |

Specific IgG GMCs were measured by OAc+ ELISA, by OAc− ELISA, and by the high-avidity ELISA, and rSBA GMTs were measured against strain C11.

(ii) High-avidity ELISA.

As with the standard ELISAs, only the response to the Baxter-TT vaccine was substantially reduced by prior administration of DT or Td vaccine. Otherwise, only minor differences between schedules were observed (Table 2).

(iii) rSBA.

The rSBA results for the 20% subset also tested by ELISA are shown in Table 2. The Chiron vaccine produced lower rSBA responses than either the Baxter or Wyeth vaccine. The reduction in antibody levels to the Baxter vaccine in group 1 seen with the ELISAs was also observed with the rSBA. However, the rSBA geometric mean titer (GMT) was still high and within the 95% CI of the two MCC-CRM vaccines.

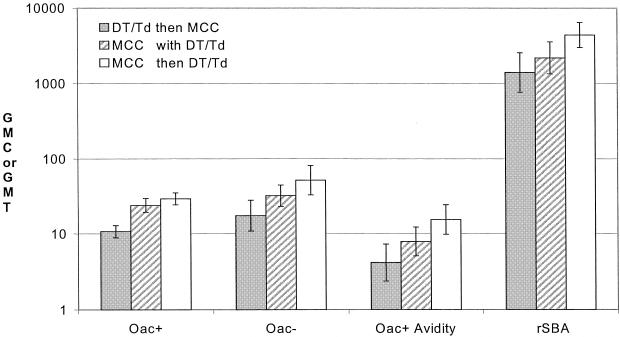

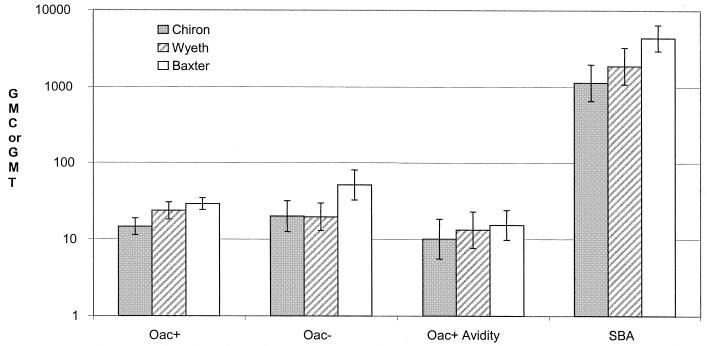

In all four assays there was a trend for the Baxter-TT vaccine to give lower antibody levels when given together with or after DT or Td vaccine than when given on its own prior to DT or Td (Fig. 1). When given prior to DT or Td (group 2), the Baxter-TT vaccine was consistently the most immunogenic of the three vaccines (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Meningococcal serogroup C IgG GMC or rSBA GMT and 95% CIs 1 month after administration of the Baxter MCC-TT vaccine, according to timing of administration of DT or Td vaccine.

FIG. 2.

Meningococcal serogroup C IgG GMC or rSBA GMT and 95% CIs 1 month after administration of the Chiron CRM, Wyeth CRM, or Baxter-TT vaccine (group 2)

Antibody levels declined significantly in the second blood sample from group 2 children, taken 8 to 10 weeks after MCC vaccination; the average drop in rSBA titer across vaccines and age groups in the 8- to 10-week post-MCC sample compared with the 4-week sample was 20.1% (95% CI, 1.7 to 35.0)

Correlation between MCC serogroup C antibody assays.

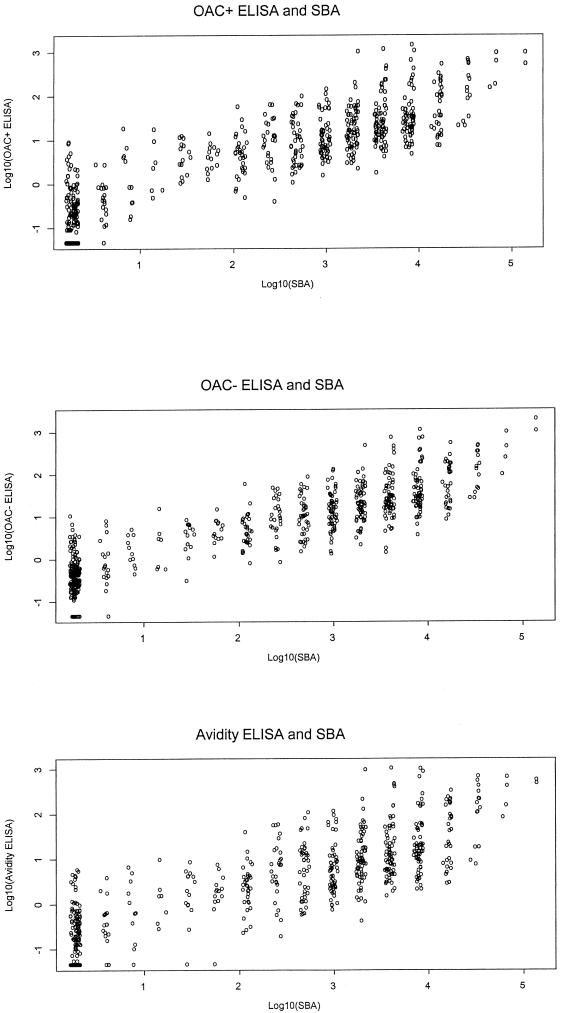

The rank correlation coefficient (r) between the three ELISAs and the rSBA was calculated for the 672 sera with results by all four assays. This included pre- and postvaccination sera and therefore covered the whole range of rSBA titers. The rank correlation was also calculated separately for the school entry and school leaver cohorts. The correlation with rSBA for the OAc+ ELISA (r = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.84 to 0.88) was similar to that for the OAc− ELISA (r = 0.87; 95% CI, 0.85 to 0.89). However, the correlation between SBA and the high-avidity ELISA was lower (r = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.81 to 0.85). The correlations between each of the three ELISAs and the rSBA are plotted in Fig. 3. The correlations were slightly higher in the school leaver cohort than in the school entry cohort (r = 0.87, 0.88, and 0.83 in school leaver cohort compared to 0.84, 0.84, and 0.81 in the school entry cohort for OAc+, OAc−, and high-avidity ELISAs, respectively). Within each vaccine, the correlations between the assays were found to be similar to the overall correlations.

FIG. 3.

Scatter plots showing results of the three ELISAs and SBA for the 672 paired sera.

Correlates of protection.

Based on SBA results generated with baby rabbit complement in clinical trials in United Kingdom infants and toddlers, a serological correlate of protection for MCC vaccines has been proposed, namely, an rSBA titer of ≥128 or an rSBA titer of 8 to 64 with a fourfold rise in rSBA titer (as used in the World Health Organization criteria for polysaccharide vaccines [17]) supported by evidence of the induction of immunologic memory (2). These rSBA criteria for protection have now been validated by postlicensure efficacy estimates for MCC vaccines which show that an rSBA titer of ≥128 is likely to be substantially higher than the threshold level for protection (12). Table 3 shows the rSBA results according to these validated criteria for the school entry and school leaver cohorts. In both groups <2% failed to achieve an rSBA titer of ≥8 and none in the 8 to 64 range with paired samples failed to develop a fourfold rise in titer. Of the 11 failing to achieve a titer of ≥8, 8 received Chiron vaccine, 2 received the Wyeth vaccine, and 1 received the Baxter vaccine.

TABLE 3.

SBA titers in the school entry and school leaver cohorts combined, categorized according to rSBA criteria of protection

| rSBA titer | School entry cohort

|

School leaver cohort

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | (%) | No. | (%) | |

| <8 | 6 | (1.9) | 5 | (1.1) |

| 8-64 | ||||

| Without fourfold rise | 0 | 0 | ||

| With fourfold rise | 19 | (4.6) | 8 | (1.8) |

| No paired sera | 19 | (4.6) | 2 | (0.5) |

| ≥128 | 373 | (89.4) | 426 | (96.6) |

| Total | 417 | 441 | ||

Serological criteria with serogroup-specific IgG levels of >2 μg/ml have also been used for meningococcal polysaccharide vaccines (15), and fourfold rises in IgG are an established measure of response for other vaccines. Fourfold rises in rSBA are already accepted as measures of a protective response for meningococcal polysaccharide vaccines (17), but the suitability of using fourfold rises in IgG concentration for polysaccharide vaccines has not been formally assessed. Tables 4 and 5 assess the sensitivity and specificity of these IgG criteria against the rSBA correlate of protection, using the results obtained with the OAc+ ELISA for those sera where appropriate samples were tested by both rSBA and ELISA. The sensitivity of ≥4-fold rises in IgG with this assay was 294/305 (96.4%), with a specificity of 1/3 (33%) (Table 4). The sensitivity of the IgG assay using the criterion of >2 μg/ml was 749/771 (97.1%), with specificity of 5/11 (45.5%). Because of the paucity of sera with no protection as measured by rSBA, it was not possible to obtain an accurate estimate of the specificities of two IgG-based serological criteria, but the 95% CIs around the specificity estimate of 46% for the threshold of >2μg/ml are 17 to 77%, so at best the specificity may only be as high as 77%.

TABLE 4.

Fourfold rise in OAc+ serogroup C-specific IgG levels categorized by serological correlate criteria according to rSBA titer for school entry and school leaver children with paired sera tested by rSBA and OAc+ ELISA

| Fourfold rise in OAc+ IgG | No.

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Protecteda | Not protected | Total | |

| Yes | 294 | 2 | 296 |

| No | 11 | 1 | 12 |

| Total | 305 | 3 | 308 |

SBA titer of ≥128 or SBA titer of 8 to 64 with a fourfold rise in rSBA (excludes sera with rSBA titers of 8 to 64 and no prevaccination sample).

TABLE 5.

OAc+ serogroup C-specific IgG levels above or below 2 μg/ml categorized by serological correlate criteria according to rSBA titer for school entry and school leaver children combined

| OAc+ IgG level of >2 μg/ml | No.

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Protecteda | Not protected | Total | |

| Yes | 749 | 6 | 755 |

| No | 22 | 5 | 27 |

| Total | 771 | 11 | 782 |

SBA titer of ≥128 or SBA titer of 8 to 64 with a fourfold rise in rSBA (excludes sera with rSBA titers of 8 to 64 and no prevaccination sample).

Response to revaccination.

A total of 53 children, 29 in the preschool cohort and 23 in school leaver cohort, who failed to achieve an rSBA titer of ≥8 or a fourfold rise in OAc+ IgG with a post-MCC concentration of >2 μg/ml were offered a second dose of MCC vaccine and bled after revaccination. All children achieved a high rSBA titer after the booster dose (GMT for the school entry cohort, 993 [95% CI, 2,821 to 8,836]; GMT for the school leaver cohort, 7,046 [4,052 to 1,1251]). The GMCs for the two groups were 49.9 (19.7 to 126.4) and 35.1 (12.8 to 96.0), respectively.

Antibody responses to TT.

The GMT antibody responses to TT are shown in Table 6. In all groups there were higher responses in the school leavers than in the school entry cohort (P < 0.001). There were also higher levels in males than in females, with an average 1.32-fold difference (P < 0.001); this difference did not vary significantly by vaccine, group, or age. There was no evidence that giving MCC with or before DT or Td reduced the response to TT, with high antibody levels being seen in the post-DT or -Td samples in all three groups (Table 6). All but seven children, five in the school entry cohort and two in the school leaver cohort, achieved antibody levels of >0.1 IU/ml.

TABLE 6.

GMTs and 95% CIs of antibody responses to TT in school entry and school leaver children according to vaccine and schedule

| Group | Vaccine | Childrena | Pre-DT or Td

|

1 mo post-DT or Td

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | GMT (95% CI) | No. | GMT (95% CI) | |||

| 1 (DT or Td, then MCC) | Chiron MCC-CRM | SE | NAb | NA | 92 | 12.5 (10.1-15.5) |

| SL | NA | NA | 107 | 19.7 (16.3-23.7) | ||

| Wyeth MCC-CRM | SE | NA | NA | 57 | 10.7 (8.2-14.0) | |

| SL | NA | NA | 76 | 19.0 (16.1-22.3) | ||

| Baxter MCC-TT | SL | NA | NA | 86 | 13.6 (10.5-17.7) | |

| SL | NA | NA | 112 | 18.4 (14.9-22.9) | ||

| 2 (MCC, then TD or Td) | Chiron MCC-CRM | SE | 78 | 0.13 (0.10-0.18) | 78 | 8.9 (6.4-12.4) |

| SL | 99 | 0.30 (0.23-0.40) | 99 | 16.9 (13.3-21.5) | ||

| Wyeth MCC-CRM | SE | 60 | 0.08 (0.06-0.11) | 60 | 9.5 (7.2-12.4) | |

| SL | 96 | 0.30 (0.23-0.39) | 96 | 21.1 (17.5-25.4) | ||

| Baxter MCC-TT | SE | 78 | 6.9 (5.1-9.3) | 78 | 15.9 (13.2-19.2) | |

| SL | 100 | 18.1 (14.4-22.7) | 100 | 18.0 (14.6-22.2) | ||

| 3 (MCC with TD or Td) | Chiron MCC-CRM | SE | 92 | 0.13 (0.10-0.16) | 92 | 11.9 (9.99-14.3) |

| SL | 104 | 0.24 (0.20-0.28) | 104 | 17.2 (14.3-20.6) | ||

| Wyeth MCC-CRM | SE | 65 | 0.10 (0.07-0.15) | 65 | 14.9 (11.8-18.8) | |

| SL | 99 | 0.28 (0.22-0.36) | 99 | 18.3 (15.9-21.2) | ||

| Baxter MCC-TT | SE | 93 | 0.08 (0.06-0.10) | 93 | 12.6 (9.9-16.1) | |

| SL | 100 | 0.39 (0.31-0.49) | 100 | 34.5 (29.6-40.2) | ||

SE, school entry cohort; SL, school leaver cohort.

NA, sample not available.

High antibody levels were also seen in group 2 in the pre-DT or -Td sample taken after the Baxter-TT vaccine. In school leavers the response to MCC-TT was similar to that after Td vaccine, but in school entry children the tetanus response to MCC-TT was lower than that to DT. In the school leaver cohort no further increase occurred in group 2 Baxter vaccine recipients when they were given Td vaccine 1 month later. However, when MCC-TT was given at the same time as Td vaccine, the antibody response was considerably augmented (GMT, 34.5) compared with the response when the two vaccines were separated by a month (GMT, 18.0). No augmentation was seen in the school entry cohort when DT and MCC-TT were given together.

Antibody responses to diphtheria toxoid.

The GMT antibody responses to diphtheria toxoid in all the groups are shown in Table 7. In group 1, higher antibody levels were achieved by the DT vaccine in the preschool cohort than by the Td vaccine in the school leaver cohort (P < 0.001), consistent with the difference in diphtheria potency of the two vaccines. Antibody levels were higher in males than in females, with an average 1.24-fold difference (P < 0.001); this difference did not vary significantly by vaccine, group, or age. There was no evidence that giving MCC with or before DT or Td reduced the response to diphtheria toxoid, with high antibody levels being seen in the post-DT or -Td samples in all three groups (Table 6). All but five children, two in the school entry cohort and three in the school leaver cohort, achieved antibody levels of >0.1 IU/ml.

TABLE 7.

GMTs and 95% CIs of antibody responses to diphtheria toxin in school entry and school leaver children according to vaccine and schedule

| Group | Vaccine | Childrena | Pre-DT or Td

|

1 mo post-DT or Td

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | GMT (95% CI) | No. | GMT (95% CI) | |||

| 1 (DT or Td, then MCC) | Chiron MCC-CRM | SE | NAb | NA | 92 | 14.1 (11.5-17.3) |

| SL | NA | NA | 107 | 4.3 (3.6-5.1) | ||

| Wyeth MCC-CRM | SE | NA | NA | 58 | 12.4 (9.3-16.4) | |

| SL | NA | NA | 76 | 4.7 (4.0-5.5) | ||

| Baxter MCC-TT | SE | NA | NA | 87 | 12.3 (9.6-15.7) | |

| SL | NA | NA | 112 | 4.5 (3.8-5.5) | ||

| 2 (MCC, then DT or Td) | Chiron MCC-CRM | SE | 78 | 7.1 (15.4-9.2) | 78 | 15.2 (12.1-19.1) |

| SL | 99 | 9.4 (7.2-12.3) | 99 | 10.9 (8.7-13.7) | ||

| Wyeth MCC-CRM | SE | 61 | 5.4 (3.6-8.2) | 61 | 12.4 (9.5-16.3) | |

| SL | 96 | 13.5 (10.0-18.2) | 96 | 15.4 (12.4-19.1) | ||

| Baxter MCC-TT | SE | 78 | 0.08 (0.07-0.10) | 78 | 9.7 (7.4-12.8) | |

| SL | 100 | 0.43 (0.33-0.56) | 100 | 4.4 (3.5-2.7) | ||

| 3 (MCC with DT or Td) | Chiron MCC-CRM | SE | 92 | 0.07 (0.05-0.09) | 92 | 15.3 (12.6-18.5) |

| SL | 104 | 0.20 (0.16-0.25) | 104 | 10.4 (9.4-13.8) | ||

| Wyeth MCC-CRM | SE | 65 | 0.06 (0.04-0.08) | 65 | 15.0 (12.1-18.7) | |

| SL | 99 | 0.21 (0.17-0.27) | 99 | 18.7 (15.1-23.2) | ||

| Baxter MCC-TT | SE | 93 | 0.06 (0.05-0.08) | 93 | 10.4 (8.0-13.6) | |

| SL | 100 | 0.36 (0.27-0.46) | 100 | 4.3 (3.8-5.0) | ||

SE, school entry cohort; SL, school leaver cohort.

NA, sample not available.

In the school leaver cohort, the antibody responses were substantially augmented by prior or simultaneous administration of the two MCC-CRM vaccines. In group 2, the antibody levels after the two MCC-CRM vaccines were significantly higher than after the Td vaccine in group 1. In the preschool children the titers after the two MCC-CRM vaccines were lower than those after the DT vaccine. These responses are consistent with the diphtheria antigen content of the vaccines (DT > MCC-CRM > Td).

For the subset of 43 sera selected at random from pre- and postvaccination sera and tested by Vero cell assay for anti-diphtheria toxin antibodies, correlation with ELISA was high (r = 0.9); however, the results by Vero cell assay were about 28% higher on average.

DISCUSSION

The primary aim of this study was to determine whether, in preschool children and school leavers, administration of diphtheria and tetanus booster vaccines at the same time, before, or after meningococcal conjugate vaccine had an effect (positive or negative) on the immune responses to any vaccine. No clinically relevant negative interactions were identified, and in all groups immune responses that were indicative of protection developed against the diphtheria, tetanus, and meningococcal antigens in all or almost all children.

The only adverse effect on immunogenicity of the MCC vaccines arising from an interaction was seen with the MCC-TT vaccine, where rSBA and IgG levels were reduced (although not below the protective threshold) by prior and, to a lesser extent, by concomitant administration of DT or Td vaccine. This phenomenon, termed carrier-induced epitopic suppression, has previously been described in the context of conjugate vaccines (1) and is thought to be due to the expansion of carrier-specific B cells (TT in this case) and subsequent intramolecular antigenic competition between polysaccharide and tetanus epitopes.

Significant increases in diphtheria antitoxin levels were generated by the MCC-CRM vaccines, and significant tetanus antitoxin responses were generated by the MCC-TT vaccine. In general, the responses to diphtheria toxin corresponded to the amount of antigen given. The tetanus responses were higher in school leavers than in school entry children for all tetanus-containing vaccines and were not related to the antigen content of the vaccine. This may reflect a stronger boosting in an older population or the effect of the earlier booster given at school entry.

All three MCC vaccines were highly immunogenic after a single dose in both the school entry and school leaver cohorts, with 94 and 98%, respectively, achieving protective titers by rSBA criteria. When vaccines in group 2 (MCC and then DT or Td) were compared, the Baxter vaccine was consistently the most immunogenic; it has been noted that stability problems may lead to reduced immunogenicity of some CRM vaccines (9).

The large number of children in the study provided an ideal opportunity to determine whether, as claimed (8), avidity ELISAs correlate better with rSBA than do conventional ELISAs. For the two age groups and three conjugate vaccines studied, the standard ELISA (whether with OAc+ or OAc− polysaccharide) showed a marginally higher correlation with rSBA than the avidity ELISA. It is possible that conjugate vaccines in the age groups we studied induce predominantly high-avidity antibodies. Low-avidity antibodies, which account for major differences in titers between standard and avidity ELISAs, may be induced in younger age groups and/or with nonconjugated vaccines, and the avidity ELISA may therefore correlate better with SBA under these circumstances. We intend to measure avidity indices (i.e., the strength with which antibodies bind to their target antigen) in the sera from the present study and to compare these with the avidity indices in toddlers and adults following MCC vaccine administration already published for these two age groups (6, 16).

Compared with rSBA criteria, putative correlates of protection based on fourfold rises in meningococcal serogroup C IgG or on IgG levels of >2 μg/ml had high sensitivity (96.4 and 97.1%, respectively), but it was difficult to assess specificity due to the small number of sera that failed to meet the rSBA protective titer. Without information on specificity of IgG criteria, it is important that reliance continues to be placed on functional antibody measurements as indicators of protective efficacy.

However, for phase 2 immunogenicity studies designed, for example, to establish batch-to-batch variability, the use of ELISAs that have a strong correlation with SBA for the particular age group and vaccines to which they will be applied would seem to be adequate. In our study, for example, in group 2 (MCC and then DT or Td) the ELISAs showed a pattern of immunogenic responses across the three vaccines similar to that seen with rSBA, and all identified the interfering effect of prior or concomitant administration of DT or Td vaccines on the response to MCC-TT. Given the constraints in conducting large numbers of SBAs, our study indicates that the use of a validated ELISA for phase 2 studies designed to establish immunological equivalence or to identify clinically important interactions would be appropriate.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study nurses in Hertfordshire and Gloucestershire who recruited, vaccinated, and followed up the study children; Rhonwen Morris for her help in organizing the study at the Gloucestershire site; and Pauline Waight, Joan Vurdien, and Teresa Gibbs for their help in study administration and data management. We thank David Salisbury for support of the study.

This study was funded by the Research and Development Directorate of the United Kingdom Department of Health, grant reference number 1216520.

Editor: J. D. Clements

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrington, T., M. Skettrup, L. Jual, and C. Heilman. 1993. NM-epitope specific suppression of antibody response to Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine by preimmunization with vaccine components. Infect. Immun. 61:432-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borrow, R., N. Andrews, D. Goldblatt, and E. Miller. 2001. Serological basis for use of meningococcal serogroup C conjugate vaccines in the United Kingdom: a reevaluation of correlates of protection. Infect. Immun. 69:1568-1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borrow, R., E. Longworth, S. J. Gray, and E. B. Kaczmarski. 2000. Prevalence of de-O-acetylated serogroup C meningococci before the introduction of meningococcal serogroup C conjugate vaccines in the United Kingdom. FEMS. Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 28:189-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borrow, R., P. Richmond, E. B. Kaczmarski, A. Iverson, S. L. Martin, J. Findlow, M. Acuna, E. Longworth, R. O'Connor, J. Paul, and E. Miller. 2000. Meningococcal serogroup C-specific IgG antibody responses and serum bactericidal titres in children following vaccination with a meningococcal A/C polysaccharide vaccine. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 28:79-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gheesling, L. L., G. M. Carlone, L. Pais, L. B. Pais, P. F. Holder, S. E. Maslanka, B. D. Plikaytis, M. Achtman, P. Densen, C. E. Frasch, H. Käyhty, J. P. Mays, L. Nencioni, C. Peeters, D. C. Phipps, J. T. Poolman, E. Rosenqvist, G. R. Siber, B. Thiesen, J. Tai, C. M. Thompson, P. P. Vella, and J. D. Wenger. 1994. Multicenter comparison of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup C anti-capsular polysaccharide antibody levels measured by a standardized enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1475-1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldblatt, D., R. Borrow, and E. Miller. 2002.. Natural and vaccine induced immunity and immunological memory to Neisseria meningitidis serogroup C in young adults. J. Infect. Dis. 185:397-400. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Goldschneider, I., E. C. Gotschilich, and M. S. Artenstein. 1969. Human immunity to the meningococcus. I. The role of humoral antibodies. J. Exp. Med 129:1307-1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granoff, D. M., S. E. Maslanka, G. M. Carlone, B. D. Plikaytis, G. F. Santos, A. Mokatria, and H. V. Raff. 1998. A modified enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for measurement of antibody responses to meningococcal C polysaccharide that correlate with bactericidal responses. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 5:479-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho, M. M., B. Bolgiano, and M. J. Corbel. 2001. Assessment of stability and immunogenicity of meningococcal polysaccharide C-CRM 197 conjugate vaccines. Vaccine 19:716-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holder, P. K., S. E. Maslanka, L. B. Pais, J. Dykes, B. D. Plikaytis, and G. M. Carlone. 1995. Assignment of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A and C class-specific anticapsular antibody concentrations to the new standard reference. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2:132-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maslanka, S. E., L. L. Gheesling, D. E. LiButti, K. B. J. Donaldson, H. S. Harakeh, J. K. Dykes, F. F. Arhin, S. J. N. Devi, C. E. Frasch, J. C. Huang, P. Kris-Kuzemenska, R. D. Lemmon, M. Lorange, C. C. A. M. Peeters, S. Quataert, J. Y. Tai, and G. M. Carlone. 1997. Standardization and a multilaboratory comparison of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A and C serum bactericidal assays. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4:156-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller, E., D. Salisbury, and M. Ramsay. 2002. Planning, registration, and implementation of an immunisation campaign against meningococcal serogroup C disease in the UK: a success story. Vaccine 20:S58-S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramsay, M. E., N. Andrews, E. B. Kaczmarski, and E. Miller. 2001. Efficacy of meningococcal serogroup C vaccine in teenagers and toddlers in England. Lancet 357:195-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redhead, K., D. Sesardic, S. E. Yost, A. M. Atwell, C. S. Hoy, J. E. Plumb, and M. J. Corbel. 1994. Interaction of Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines with diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine in control tests. Vaccine 12:1460-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richmond, P., R. Borrow, D. Goldblatt, J. Findlow, S. Martin, R. Morris, K. Cartwright, and E. Miller. 2001. Ability of three different meningococcal C conjugate vaccines to induce immunological memory after a single dose in UK toddlers. J. Infect. Dis. 183:160-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richmond, P. C., R. Borrow, E. Miller, S. Clark, F. Sadler, A. J. Fox, N. T. Begg, R. Morris, and K. A. V. Cartwright. 1999. Meningococcal serogroup C conjugate vaccine is immunogenic in infancy and primes for memory. J. Infect. Dis. 179:1569-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. 1976. Requirements for meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine. World Health Organization Technical Report series, no. 594. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.