Abstract

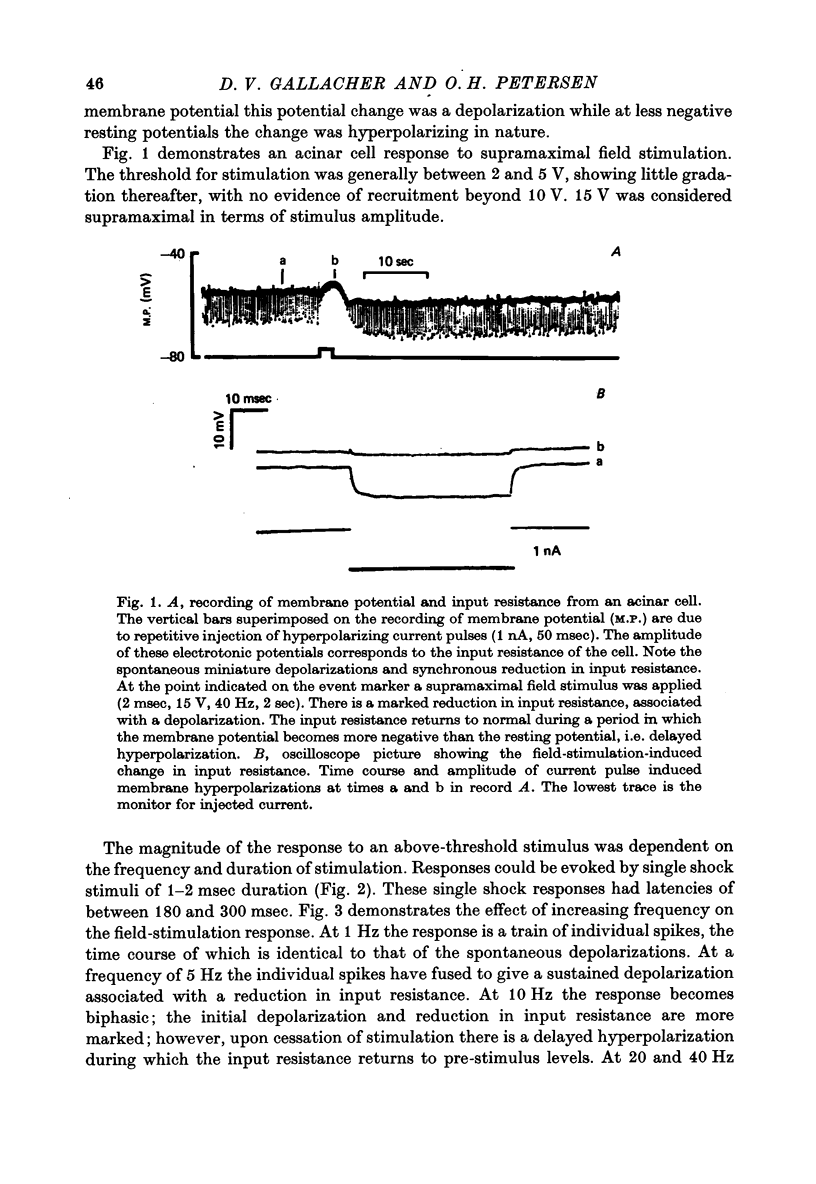

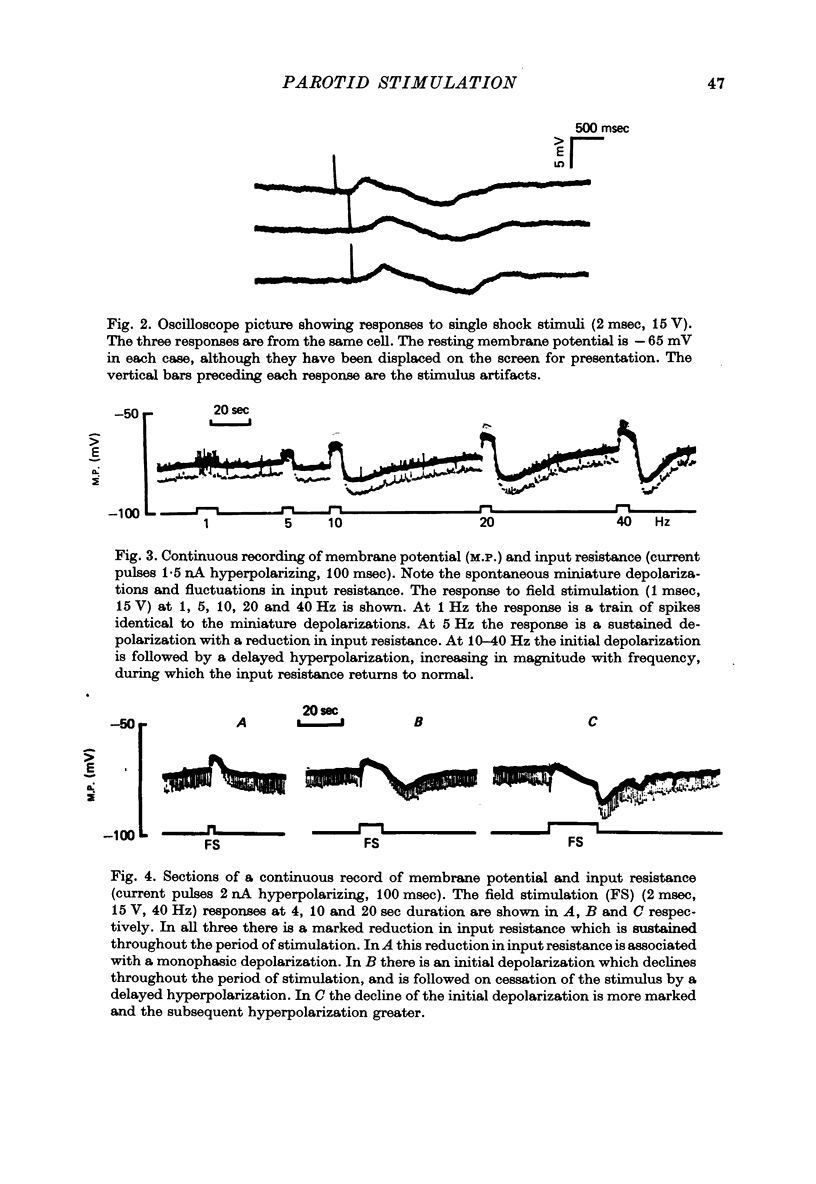

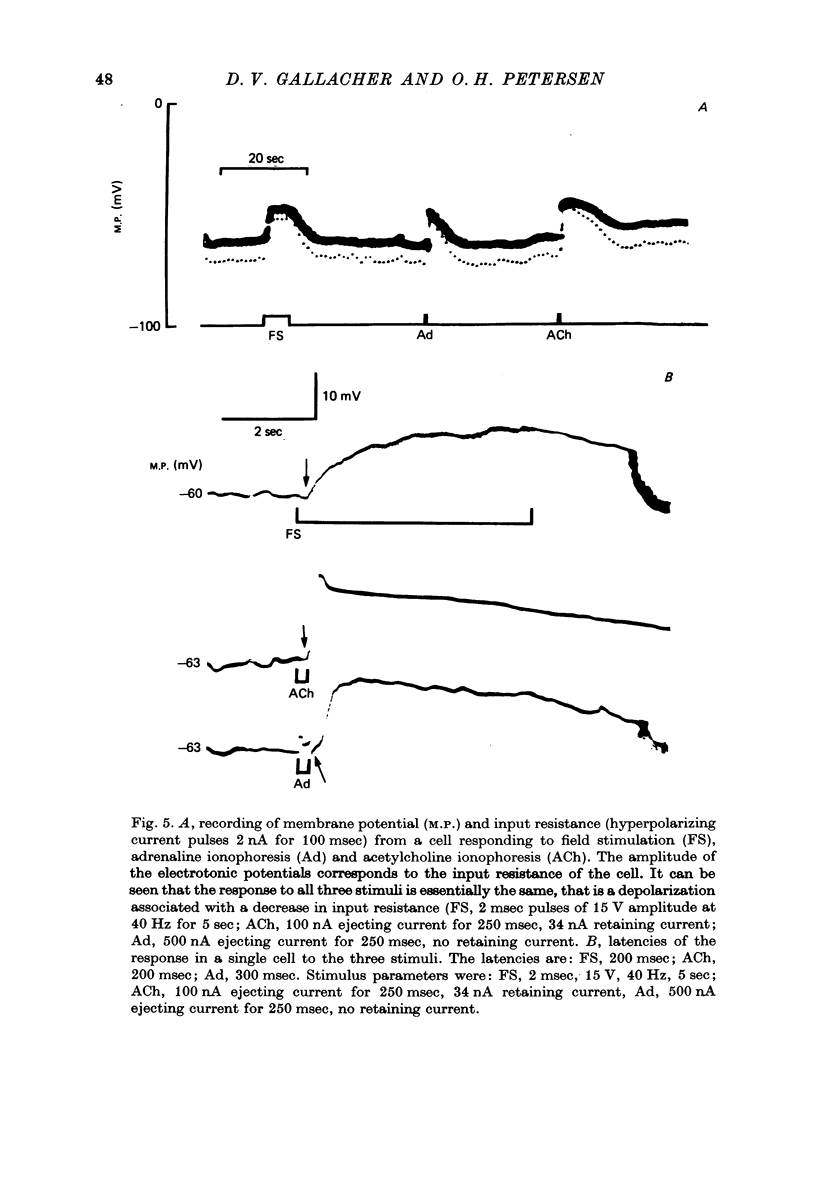

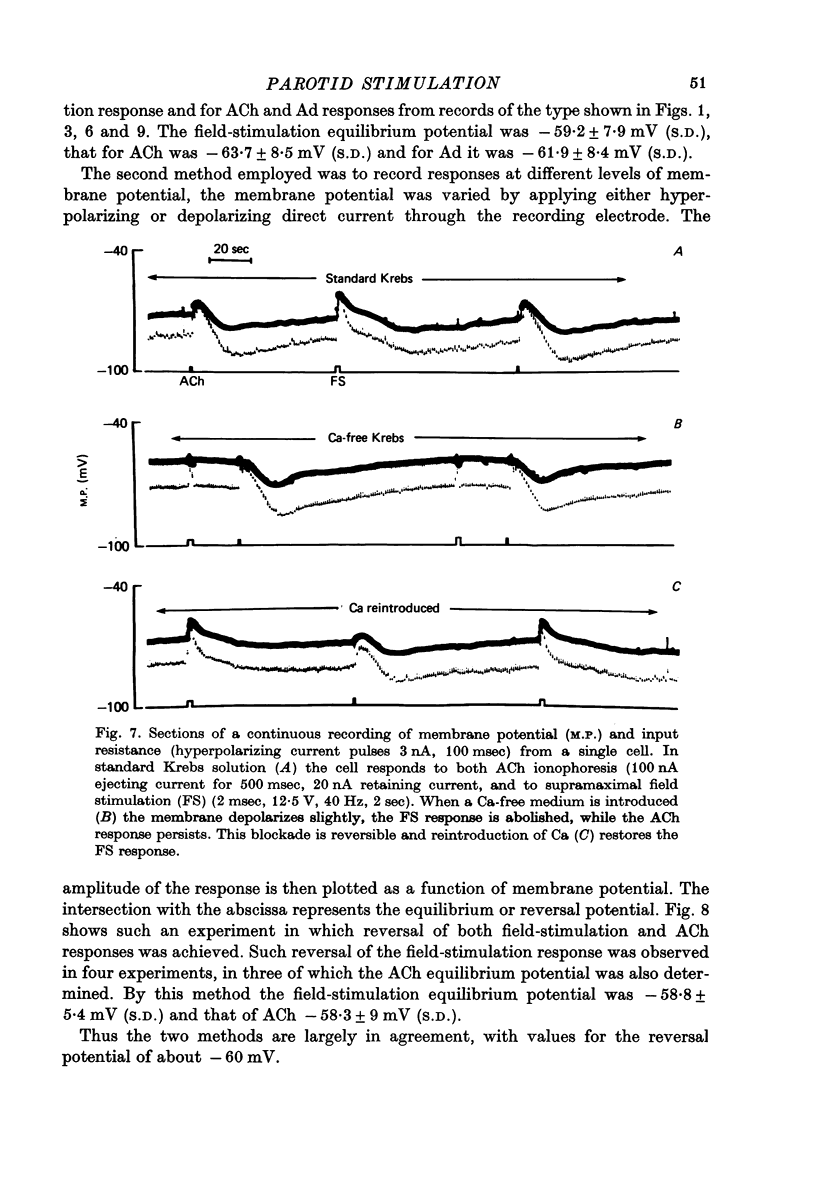

1. Intracellular micro-electrode recordings of membrane potential and input resistance were made from surface acini of mouse parotid glands placed in a Perspex tissue bath through which oxygenated physiological saline solutions were circulated. The acinar cells were stimulated by microionophoresis of both acetylcholine (ACh) and adrenaline (Ad) from extracellular micropipettes, and by electrical field stimulation via a pair of platinum electrodes. 2. The acinar cells had a mean resting membrane potential of -64.9 mV +/- 0.6 S.E. The input resistance of the unstimulated cell was 4.63 M omega +/- 0.19 S.E. In a number of cells spontaneous miniature depolarizations were observed, associated with synchronous reductions in input resistance. 3. The responses to ionophoresis of both ACh and Ad and the response to supra-maximal field stimulation were identical. Stimulation always evoked a marked decrease in input resistance associated with an initial potential change, generally followed by a delayed hyperpolarization during which the input resistance returned to normal. 4. Field-stimulation responses could be evoked to single shock (1-2 msec) and to low frequency (1-4 Hz) stimulation. The latency for this response was 245 msec +/- 12 S.E. 5. The field-stimulation response was shown to be susceptible to blockade of nerve conduction in sodium-free or tetrodotoxin- (TTX-) containing media; and to blockade of neurotransmitter release in calcium-free media. 6. The field-stimulation and ACh responses were recorded at different levels of membrane potential within the same cells by applying either hyperpolarizing or depolarizing direct current through the recording electrode. The membrane potential at which the initial potential change undergoes reversal, i.e. changes from a depolarization to a hyperpolarization, is known as the equilibrium or reversal potential, EFS and EACh respectively. The field-stimulation (FS) and ACh responses underwent simultaneous reversal at about -60 mV, i.e. EFS = EACh. Equilibrium potentials were also determined indirectly by analysis of the responses evoked by each stimulus in the manner described by Trautwein & Dudel (1958). Using this technique the equilibrium potentials of the responses to all three stimuli, field stimulation, ACh and Ad, were again about -60mV, i.e. EFS = EACh = EAd. 7. Both the field-stimulation and ACh responses were abolished by atrophine (10(-6) M) while the response to Ad persisted. Atropine also abolished all spontaneous activity. The alpha-adrenergic blocker phentolamine (10(-5) M) abolished the response to Ad but left the field-stimulation response unaffected. 8. Electrical field stimulation of isolated segments of salivary gland evoked release of endogenous neurotransmitter as a consequence of neural excitation. The technique of field stimulation thus makes it possible to investigate the functional innervation of a gland using the in vitro preparation. In the mouse parotid gland the field stimulus response was mediated by ACh released from parasympathetic nerve endings.

Full text

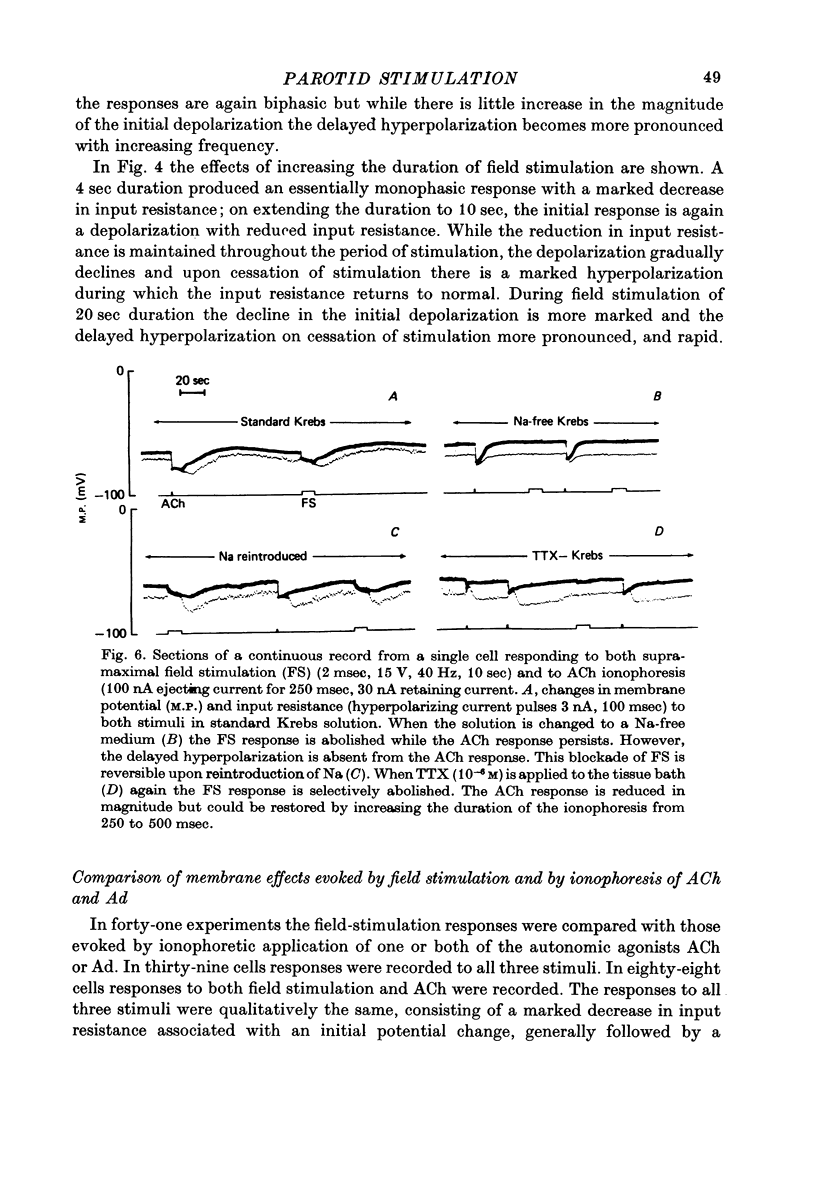

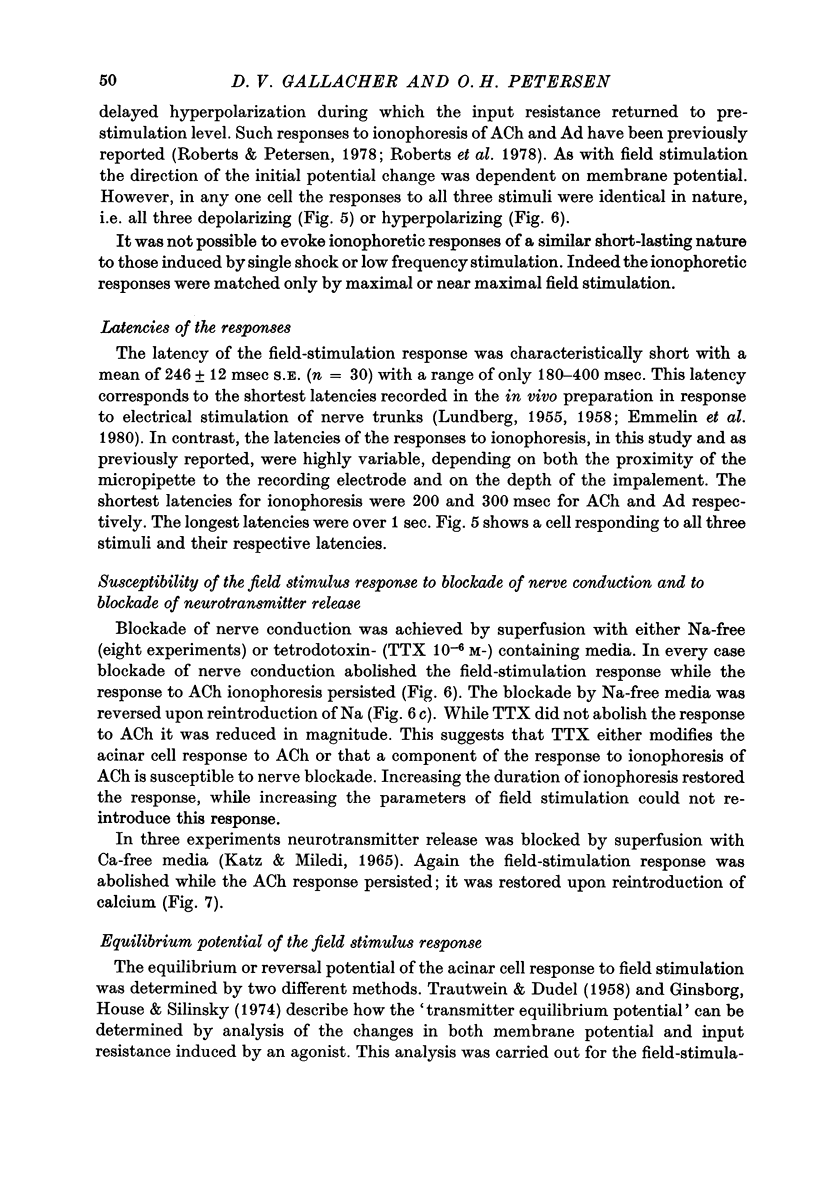

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

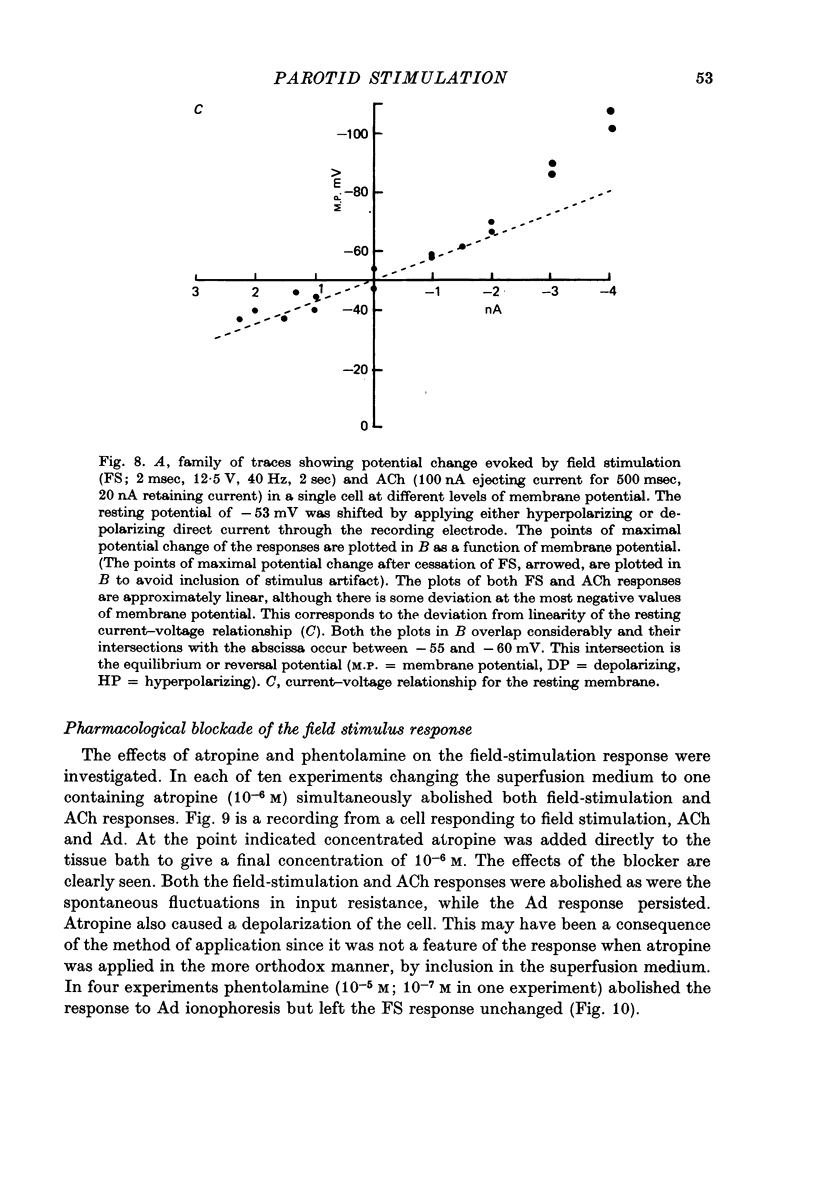

- Adrian R. H., Slayman C. L. Membrane potential and conductance during transport of sodium, potassium and rubidium in frog muscle. J Physiol. 1966 Jun;184(4):970–1014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

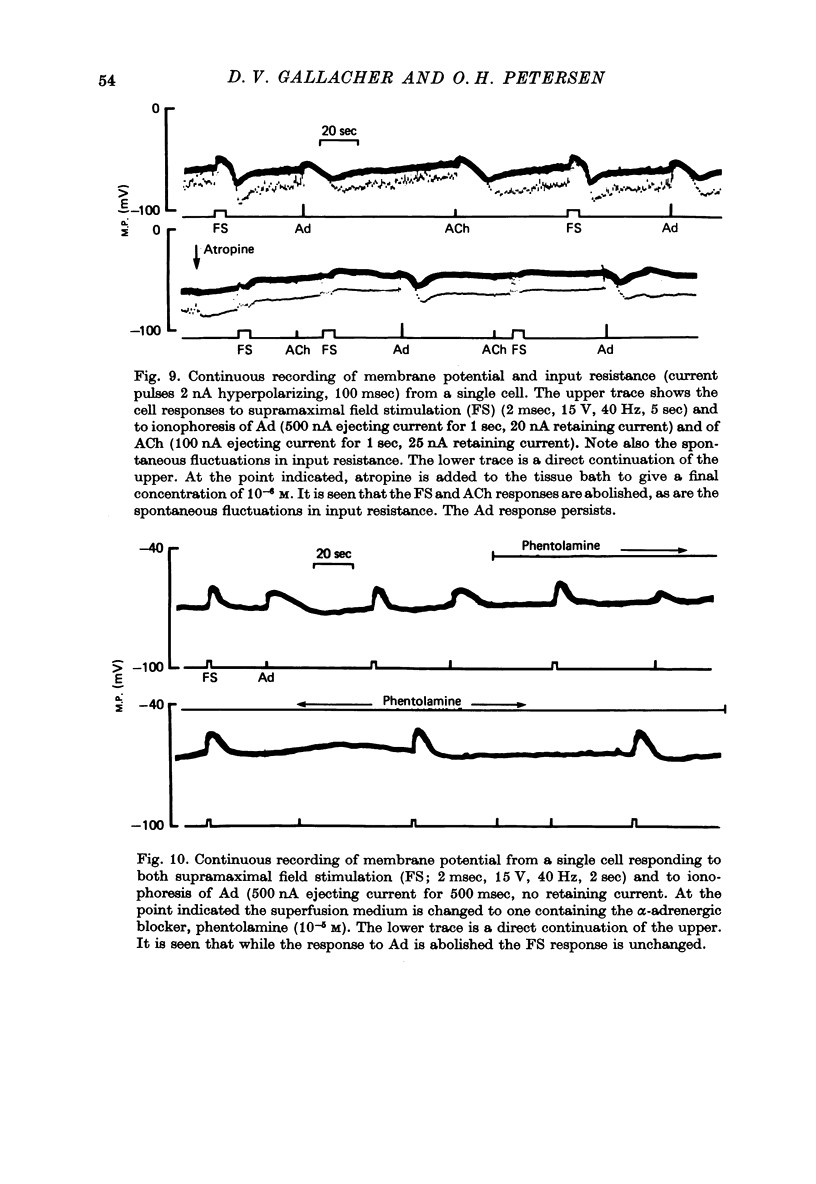

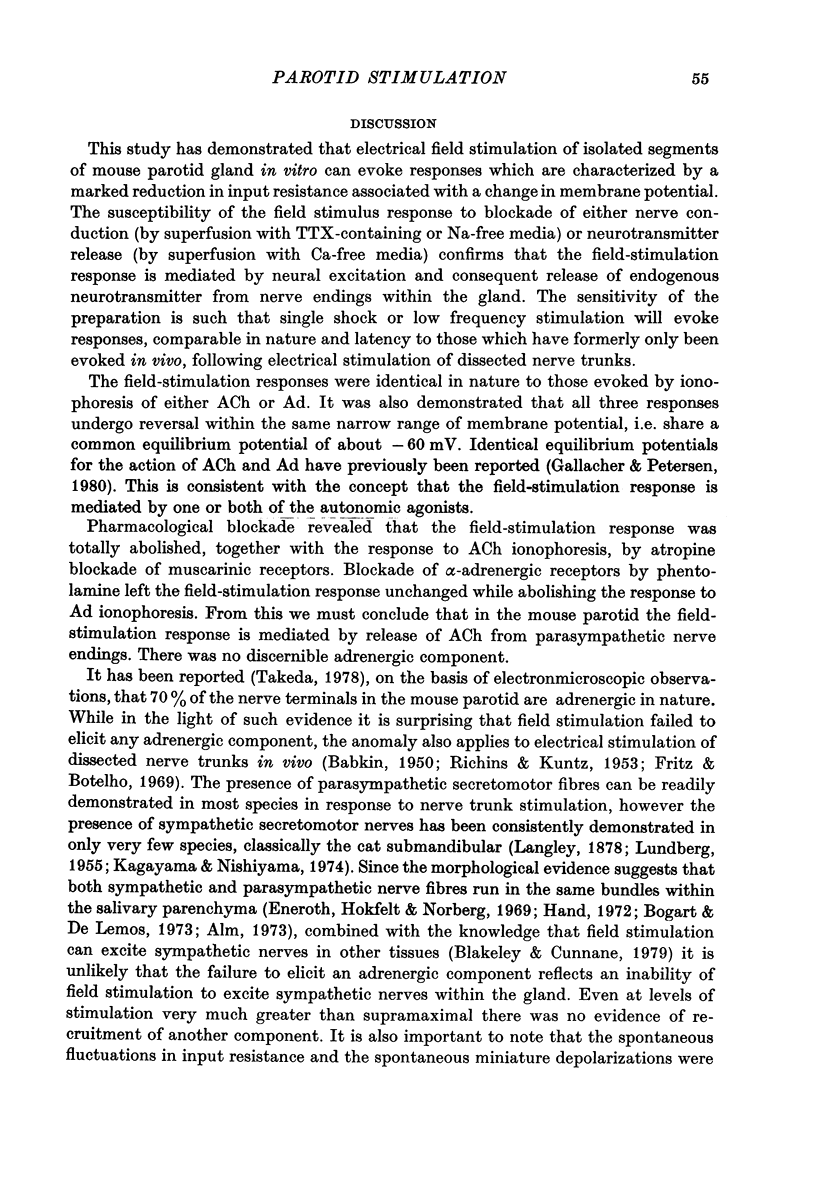

- Alm P. Adrenergic and cholinergic nerves of bovine, guinea pig and hamster salivary glands. A light and electron microscopic study. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1973 Apr 17;138(3):407–420. doi: 10.1007/BF00307102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakeley A. G., Cunnane T. C. Packeted transmitter release in the mouse vas deferens; an electrophysiological study [proceedings]. J Physiol. 1979 Oct;295:44P–45P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart B. I., De Lemos C. L. Adrenergic innervation of the rat submandibular and parotid glands. An electron microscopic autoradiographic study of the uptake of tritiated norepinephrine. Anat Rec. 1973 Oct;177(2):219–223. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091770204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casteels R., Droogmans G., Hendrickx H. Active ion transport and resting potential in smooth muscle cells. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1973 Mar 15;265(867):47–56. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1973.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean P. M., Matthews E. K. Pancreatic acinar cells: measurement of membrane potential and miniature depolarization potentials. J Physiol. 1972 Aug;225(1):1–13. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmelin N., Grampp W., Thesleff P. Sympathetically evoked secretory potentials in the parotid gland of the cat. J Physiol. 1980 May;302:183–195. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eneroth C. M., Hökfelt T., Norberg K. A. The role of the parasympathetic and sympathetic innervation for the secretion of human parotid and submandibular glands. Acta Otolaryngol. 1969 Nov;68(5):369–375. doi: 10.3109/00016486909121575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FATT P., KATZ B. Spontaneous subthreshold activity at motor nerve endings. J Physiol. 1952 May;117(1):109–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz M. E., Botelho S. Y. Membrane potentials in unstimulated parotid gland of the cat. Am J Physiol. 1969 May;216(5):1180–1183. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1969.216.5.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallacher D. V. Parotid acinar cells: membrane potential changes induced by electrical field stimulation [proceedings]. J Physiol. 1979 Oct;295:46P–47P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallacher D. V., Petersen O. H. Substance P increases membrane conductance in parotid acinar cells. Nature. 1980 Jan 24;283(5745):393–395. doi: 10.1038/283393a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsborg B. L., House C. R., Silinsky E. M. Conductance changes associated with the secretory potential in the cockroach salivary gland. J Physiol. 1974 Feb;236(3):723–731. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hand A. R. Adrenergic and cholinergic nerve terminals in the rat parotid gland. Electron microscopic observations on permanganate-fixed glands. Anat Rec. 1972 Jun;173(2):131–139. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091730202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsuki N., Petersen O. H. Membrane potential, resistance, and intercellular communication in the lacrimal gland: effects of acetylcholine and adrenaline. J Physiol. 1978 Feb;275:507–520. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATZ B., MILEDI R. THE EFFECT OF CALCIUM ON ACETYLCHOLINE RELEASE FROM MOTOR NERVE TERMINALS. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1965 Feb 16;161:496–503. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1965.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagayama M., Nishiyama A. Membrane potential and input resistance in acinar cells from cat and rabbit submaxillary glands in vivo: effects of autonomic nerve stimulation. J Physiol. 1974 Oct;242(1):157–172. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUNDBERG A. Electrophysiology of salivary glands. Physiol Rev. 1958 Jan;38(1):21–40. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1958.38.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUNDBERG A. The electrophysiology of the submaxillary gland of the cat. Acta Physiol Scand. 1955 Dec 22;35(1):1–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1955.tb01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel I. D., Zengo A., Katz R., Wotman S. Effect of adrenergic agents on salivary composition. J Dent Res. 1975 Jun;54(SPEC):B27–B33. doi: 10.1177/00220345750540022001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama A., Petersen O. H. Membrane potential and resistance measurement in acinar cells from salivary glands in vitro: effect of acetylcholine. J Physiol. 1974 Oct;242(1):173–188. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen G. L., Petersen O. H. Membrane potential measurement in parotid acinar cells. J Physiol. 1973 Oct;234(1):217–227. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen O. H. The dependence of the transmembrane salivary secretory potential on the external potassium and sodium concentration. J Physiol. 1970 Sep;210(1):205–215. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M. L., Iwatsuki N., Petersen O. H. Parotid acinar cells: ionic dependence of acetylcholine-evoked membrane potential changes. Pflugers Arch. 1978 Sep 6;376(2):159–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00581579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M. L., Petersen O. H. Membrane potential and resistance changes induced in salivary gland acinar cells by microiontophoretic application of acetylcholine and adrenergic agonists. J Membr Biol. 1978 Mar 20;39(4):297–312. doi: 10.1007/BF01869896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAUTWEIN W., DUDEL J. Zum Mechanismus der Membranwirkung des Acetylcholin an der Herzmuskelfaser. Pflugers Arch. 1958;266(3):324–334. doi: 10.1007/BF00416781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda M. Electron microscopy of the adrenergic and cholinergic nerve terminals in the mouse salivary glands. Arch Oral Biol. 1978;23(10):857–864. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(78)90287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]