Abstract

We analyzed the LKP fimbrial gene clusters of six piliated strains of a cryptic genospecies of Haemophilus isolated from the genital tracts of adult patients (five strains) and from an infected neonate. In a group of 19 genital strains, LKP-like genes have been found in only these 6 strains. In addition to the ghfA, ghfD, and ghfE genes previously described, we characterized two genes, designated ghfB and ghfC, encoding the putative chaperone and assembly platform proteins. All six strains had a complete and unique LKP-like gene cluster consisting of the five genes ghfA to ghfE, homologous to genes hifA to hifE of Haemophilus influenzae. The sequences of the coding and intergenic regions of the ghf clusters of the six strains were remarkably homologous. Unlike hif clusters, which are inserted between purE and pepN, the ghf cluster was inserted between purK and pepN on the chromosome. Analysis of the flanking regions of the ghf cluster identified a large deletion, identical in the 5′ end regions of all strains, including the whole purE gene and much of the purK gene. Ultrastructural observations, an attempt at enriching LKP fimbriae, and hemagglutination experiments demonstrated that none of the strains had LKP-type fimbriae. Nevertheless, reverse transcription (RT)-PCR showed that ghf genes were transcribed in four of the six strains. Sequencing of the intergenic ghfA-ghfB regions, including the ghf gene promoters, showed that the absence of transcripts in the remaining two strains was due to a decrease in the number of TA repeats (4 or 9 repeats rather than 10) between the −10 and −35 boxes of the two overlapping and divergent promoters. The other four strains, which had ghf transcripts, had the optimal 10 TA repeats (one strain) or 5 repeats associated with putative alternative −35 boxes (three strains). The absence of 10 repeated palindromic sequences of 44 or 45 nucleotides upstream of ghfB induces an increased instability of mRNA, as quantified by real-time RT-PCR, and may explain why the LKP fimbrial gene cluster is not expressed in these strains.

Haemophilus influenzae strains are gram-negative rods that colonize the human respiratory and genital mucosa and are responsible for respiratory tract infections, meningitis, and genital and neonatal infections (19, 30). A group of Haemophilus strains, almost all identified as nontypeable H. influenzae (NTHi) of biotype IV, have been specifically isolated from patients with neonatal, mother-infant, and genital tract infections (1, 16, 17, 22, 33). Genetic analysis showed that these strains constitute a cryptic genital genospecies that forms a monophyletic unit with Haemophilus haemolyticus and H. influenzae (20, 21, 23). These strains adhere more strongly to HeLa cells of genital origin than to HEp-2 cells of respiratory tract origin and do not cause the agglutination of human erythrocytes expressing the AnWj antigen (27). Most strains express peritrichous fimbriae that probably act as adhesins and that may enable the strain to survive in the genital tract.

Several morphologically and functionally different fimbriae have been observed in both type b (Hib) and nontypeable respiratory isolates of H. influenzae. Many NTHi strains express thin and hemagglutination-negative fimbriae (3, 4, 28). The principal fimbrial gene cluster studied in Hib and NTHi encodes long, thick, and hemagglutination-positive (LKP) fimbriae. The LKP fimbrial gene cluster contains five genes, hifA to hifE, and is regulated by two overlapping and inverted promoters located between hifA and hifB (8, 24, 31, 32). The first promoter initiates the transcription of hifA. The second promoter initiates the transcription of the four genes hifBCDE. In a previous study, we tried to identify several LKP-like fimbrial genes in a group of 19 strains genetically assigned to the cryptic genital Haemophilus genospecies. In six strains, we identified, by Southern blotting and PCR, three hif-like genes named ghfA, ghfD, and ghfE encoding the putative major pilus structural component and two minor proteins (9). Nevertheless, the fimbrial morphology on electron microscopy and the hemagglutination properties observed were not characteristic of LKP-type fimbriae (27). Similarly, in a recent study, Clemans et al. reported the presence of two hif genes in six genital and neonatal biotype IV NTHi strains but the absence of hif gene products and of hemagglutinating fimbriae (5). Thus, a complete study of the hif-like cluster of genital strains appeared to be necessary to evaluate the general organization of the cluster, its location, the sequence of each gene, the transcription of fimbrial genes, and the production of fimbriae.

In this study, we completed the identification of the LKP-like fimbrial-gene clusters of six piliated biotype IV NTHi genital strains. We described two genes, designated ghfB and ghfC, encoding the putative chaperone and assembly platform proteins, and the junction between the pilus gene cluster and the bordering genes. We analyzed the DNA sequence of the promoter region and investigated whether ghf gene trancripts were present in an attempt to determine the reason for the absence of LKP fimbriae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Eight Haemophilus strains were studied, including seven strains previously assigned to the cryptic genital Haemophilus genospecies on the basis of DNA-DNA hybridization and small-subunit ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequencing. Six strains (10U, 11PS, 26E, 2406, PIZ, and 15N) possess the hif-like genes ghfA, ghfD, and ghfE, and the strain 16N lacks ghf and hif genes (9). Strains 15N and 16N were isolated from infected neonates. The other five strains were isolated from the genital tracts of adult patients. An acapsular variant of Hib (strain 770235) harboring LKP fimbriae, kindly provided by L. van Alphen (Department of Medical Microbiology, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), was used as a control for hif genes (32). The strains were stored at −80°C in Schaedler-vitamin K3 broth (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) with 10% glycerol. The bacteria were grown for 12 to 24 h on chocolate agar plates (bioMérieux) or in Schaedler-vitamin K3 broth supplemented with 10% globular extract (Bio-Rad SA, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) at 37°C in 8% CO2-92% air.

Electron microscopy.

The presence and appearance of fimbriae were examined by electron microscopy before and after the procedure described by Connor and Loeb (6) for the enrichment of LKP fimbriae with human erythrocytes. The bacteria were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline and allowed to settle on 400-mesh copper grids coated with carbon film. They were negatively stained with 1.5% uranyl acetate in distilled water and then examined with a JEOL 1010 electron microscope at 80 kV.

Hemagglutination assays.

The abilities of twofold dilutions of bacteria to hemagglutinate O+ human erythrocytes were determined in V-shaped microtiter trays, as described by Pichichero (18). The trays were incubated at room temperature for 1 h, and the highest dilution giving visible hemagglutination was recorded.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR.

Total cellular RNA was extracted from bacteria grown to mid-log phase by standard methods (29). To eliminate contaminating genomic DNA, 5 μg of total RNA was incubated with 10 U of DNase (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium) for 10 min at 25°C. Reverse transcription (RT) was performed with the Superscript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Cergy-Pontoise, France) using random hexamers and 300 ng of DNase-treated RNA according to the manufacturer's instructions. Identical aliquots of RNA were processed in parallel without the addition of reverse transcriptase to ensure that residual genomic DNA was not serving as the template in subsequent PCR amplification.

PCR assay.

Genomic DNA (20 ng), extracted and purified as previously described (9), or cDNA was used as the template for PCR. Primers (Eurogentec) (Table 1) were designed to correspond to conserved sequences in the hif genes of the Hib strain 770235 (32), in the flanking regions of the hif gene cluster (7, 32), in the ghf genes of genital strains of Haemophilus (9), and in 16S rDNA specific for the genital cryptic genospecies (23). The PCR mixture (20 μl) contained primers (0.5 μM each), deoxynucleoside triphosphates (100 μM each) (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), Taq DNA polymerase (0.3 U) (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Meylan, France), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.3), and 50 mM KCl. The PCR consisted of an initial 2.5-min hold at 94°C followed by 25 cycles, each of 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, 1 min of annealing at 55°C, and 2 min of elongation at 72°C, followed by a final 10-min elongation step (Cetus 9600; Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). For amplification of the total gene cluster, we used the conditions described by Mhlanga-Mutangadura et al. (15), with Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and the primer sets PURE451-PEPN7717rc and PURK1071-PEPN7717rc.

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide sequences of PCR primers

| Primera | Nucleotide sequence | Gene | Position | PCR product(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HB2087 | 5′ TTATGTTGAAATGGGGAAAACAAT 3′ | hifB | 2087-2110 | hifB and ghfB |

| HB2820rc | 5′ GTTATTTACGTTATTATTGTGCGA 3′ | hifB | 2820-2797 | |

| GB92 | 5′ CTGGCACCAGAGTGATTTATC 3′ | ghfB | 92-112 | Partial hifB and ghfB |

| GB446rc | 5′ CGATAAAACAACTTCAAACGTGA 3′ | ghfB | 446-424 | |

| GB177rc | 5′ TTGCACCAAGGCTGCCGAAT 3′ | ghfB | 177-158 | |

| HA654 | 5′ GTAAGCAATTTGGAAATCAACTGA 3′ | hifA | 654-677 | hifA and ghfA |

| HA1310rc | 5′ CTCTTTATGGAGCAATTTATTATG 3′ | hifA | 1310-1287 | |

| GA36 | 5′ GGCATTTGCGGGAAATGTGC 3′ | ghfA | 36-55 | Partial hifA and ghfA |

| GA122rc | 5′ CAGGTATTTTCAACAACCTTACC 3′ | ghfA | 122-100 | |

| GB651 | 5′ CAATAAATTGAAATGGGTGTTGG 3′ | ghfB | 651-673 | ghfC |

| GD43rc | 5′ TTTGATGGAAAAGTGCGGTTAAT 3′ | ghfD | 43-21 | |

| HA1251 | 5′ TGCCAATAAAATTAAGCTACCAAG 3′ | hifA | 1251-1274 | Promoter region |

| HB2157rc | 5′ CTGAAAATGCACAAAGTGCGGT 3′ | hifB | 2157-2136 | |

| PURE451 | 5′ CCATCACAACGGCAATTTGT 3′ | purE | 451-470 | Cluster 5′ flanking sequence |

| PURK1071 | 5′ CGCCCAATTTAATCCTGATTG 3′ | purK | 1071-1051 | |

| GA499 | 5′ GCAACTGAATTAAATGGTAAAACT 3′ | ghfA | 499-522 | |

| PEPN7717rc | 5′ CTGTGACCGTAAAATCTGGTT 3′ | pepN | 7717-7697 | Cluster 3′ flanking sequence |

| GE1249 | 5′ AGAGGCGATTTAACCGAAGG 3′ | ghfE | 1249-1268 |

Primers were named as follows: H corresponds to hif genes of Hib strain 770235; G corresponds to ghf genes of genital strains of Haemophilus; A, B, C, and D correspond to the respective genes (A for hifA, for example); rc indicates that primers were identical to the lagging strand; and the number corresponds to the position of the first nucleotide according to the authors' numbering system (9, 32). The PURE451, PURK1071, and PEPN7717rc primers were designed from the sequences of H. influenzae Rd genes (7).

Real-time PCR.

To quantify the mRNA, cDNA (20 ng) from the genital strains 16N and 26E and dilutions of cDNA (20, 10, 2, 1, and 0.2 ng) from the Hib strain 770235 were used as templates for fluorescence-based real-time PCR. Primers were designed, according to the manufacturer's instructions, in conserved sequences of the hif and ghf genes. The primer sets GA36-GA122rc and GB92-GB177rc (Table 1) were used to amplify an 85-bp fragment of the hifA and ghfA genes and of the hifB and ghfB genes, respectively. The PCR mixture (20 μl) was identical to that used for the PCR assay plus 0.13× SYBR Green I fluorescent dye (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). The PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2.5 min was followed by 30 cycles, each of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 2 min at 72°C, in an iCycler iQ apparatus (Bio-Rad). The fluorescence signal was measured during the elongation step of each cycle, and the threshold cycle (Ct) value was determined for each sample. Ct is defined as the point at which the fluorescence signal is first recorded as statistically significant above background. The specificity of the PCR was verified by ethidium bromide staining after electrophoresis on 3.5% agarose gels.

DNA sequencing.

PCR products were purified with Microcon 100 (Millipore, St. Quentin-en-Yvelines, France). Nucleotide sequences were determined on both strands with a Thermo Sequenase II dye terminator cycle-sequencing kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Saclay, France) and PCR primers on an ABI Prism 377 sequencer (Perkin-Elmer) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ten additional primers designed from the sequence of hifC (34) were used to sequence ghfC.

Southern blot analysis.

Two micrograms of DNA from each strain was digested overnight with 25 U of HindIII, and the restriction fragments were resolved on a 1% agarose gel and vacuum transferred onto positively charged nylon membranes (Roche Diagnostics) before overnight hybridization at 55°C. A 350-base ghfB probe was prepared by amplification of the genomic DNA of genital strain 26E with primers GB92 and GB446rc (Table 1). It was heated at 90°C and labeled with alkaline phosphatase, using the AlkPhos direct-labeling and detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The hybridized probe was detected by chemiluminescence with the CDP-Star reagent. Light emission was recorded on Hyperfilm MP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences of the chaperone protein gene (ghfB) of strain 26 E, the platform assembly protein genes (ghfC) of strains 26E and 15N, and the ghf cluster of strain 26E have been deposited in the EMBL sequence database under accession numbers AJ414543, AJ414540, AJ414539, and AJ421028.

RESULTS

Identification of the fimbrial chaperone protein gene ghfB.

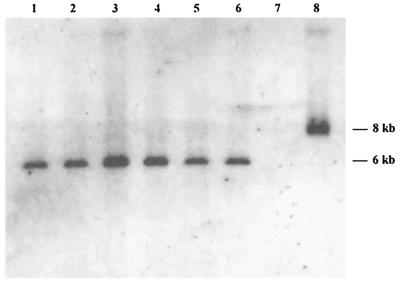

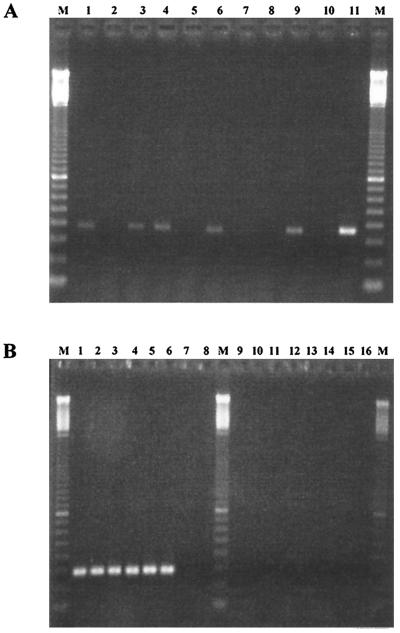

An amplified fragment of about 750 bp was obtained for each of the six genital strains possessing ghf genes and for the Hib control strain for hif genes, using the HB2087 and HB2820rc primers (Table 1), which bind to the extreme ends of the hifB gene of Hib strain 770235. The nucleotide sequences of the fragments amplified were determined for three genital strains (10U, PIZ, and 26E). They were strictly identical and included a 720-bp open reading frame (ORF), which we designated ghfB for genital Haemophilus fimbria gene B. ghfB was about 400 bp upstream of ghfA and oriented in the opposite direction. It was 93% identical to the hifB gene of the Hib control strain, 770235 (32). It encoded a 239-amino acid protein (GhfB), with a predicted signal sequence of 23 residues, that was 94% identical and 96% similar to the 770235 HifB chaperone protein for LKP fimbrial subunits. This protein also displayed sequence similarity to bacterial chaperone proteins of various fimbrial gene clusters. The highest levels of identity (40 to 43%) included those to FimB of Bordetella pertussis, F17a-D of Escherichia coli, and MrkB of Klebsiella pneumoniae (2, 12, 13). Southern blotting with an intragenic ghfB probe detected a single band in the seven strains possessing hif or ghf genes (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Southern blot obtained with part of the fimbrial chaperone protein gene (ghfB) of genital Haemophilus strain 26E labeled with alkaline phosphatase and used as a probe. A single band of hybridization was detected with HindIII-restricted DNA from the genital cryptic Haemophilus strains 15N, 10U, 11PS, 26E, PIZ, and 2406 (lanes 1 to 6) and the Hib control strain, 770235 (lane 8). No hybridization was observed with the genital cryptic Haemophilus strain 16N, which lacks hif and ghf genes (lane 7).

Identification of the fimbrial platform assembly protein gene ghfC.

For the six strains of Haemophilus possessing the ghf genes, amplicons of about 2,700 bp were obtained with the GB651 and GD43rc primers (Table 1), corresponding to the 3′ end of ghfB and the 5′ end of ghfD, respectively, that likely surround the putative pilus platform assembly gene. The PCR fragments included a 2,514-bp ORF, which we designated ghfC for genital Haemophilus fimbria gene C. This ORF was read on the same strand as ghfB, ghfD, and ghfE and started, as previously reported for hifC (24, 34), with a GTG codon 117 bp 3′ of the ghfB terminus. The TAA stop codon was located 13 bp upstream of the initiation codon of ghfD. The sequences of ghfC were identical for two strains (26E and 2406) and identical for the other four strains. These two ORFs were 99.2% identical and presented 19 base changes, with two of them leading to a Ser→Thr substitution at residues 127 and 205. They were 93 to 94% identical to the sequences of hifC genes described for various strains of H. influenzae (24, 32, 34). The consensus ORF encoded an 837-amino-acid protein of approximately 93 kDa named GhfC. The sequence of GhfC was 96 to 97% identical and 98% similar to those of the HifC usher proteins of LKP fimbriae and included four conserved cysteine residues at positions 89, 116, 813, and 833. The sequence included a predicted 26-amino-acid leader sequence identical to HifC leader sequences, with a Trp-Ala↑Glu-Asp cleavage site, typical of prokaryotic secreted proteins (35). It was also 30 to 42% identical to the pilus assembly platform proteins of other gram-negative rods, including the F17-C, SfaF, FocD, and FimD proteins of E. coli and MrkC of K. pneumoniae (2, 11, 12).

Promoter region and fimbria expression.

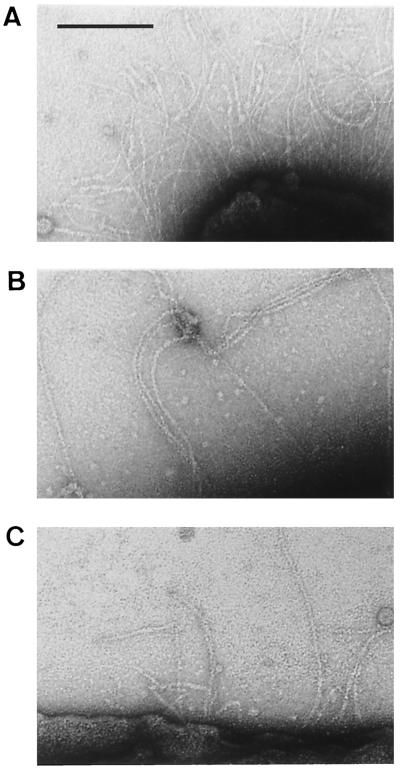

All genital strains were spontaneously abundantly fimbriated. The number and appearance of fimbriae were identical before and after five to seven enrichment cycles with human erythrocytes, according to the procedure described by Connor and Loeb for enrichment in LKP fimbriae (6). Four strains harbored thin (2-nm-diameter) and very flexible fimbriae (Fig. 2A) whose aspect was very different from that of the LKP fimbriae of Hib strain 770235 (Fig. 2B). The fimbriae of strains 11PS and PIZ (Fig. 2C) were long and thick (6-nm diameter) with horizontal striations indicative of a helical structure, similar to that of LKP fimbriae, but these strains did not agglutinate O+ human erythrocytes (hemagglutination titer, <1). Thus, no genital strain harbored LKP-type fimbriae.

FIG. 2.

Electron microscopy of Haemophilus strain fimbriae negatively stained with uranyl acetate. (A) Thin (2-nm-diameter) and very flexible fimbriae of genital Haemophilus strain 26E; (B) LKP fimbriae of H. influenzae strain 770235; (C) thick and rigid fimbriae of genital Haemophilus strain 11PS. Bar, 100 nm.

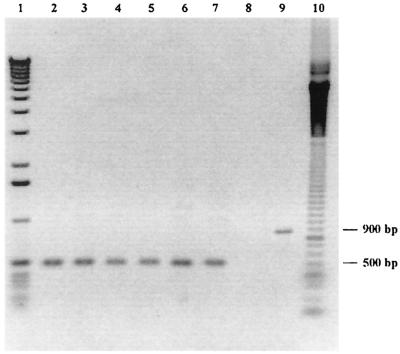

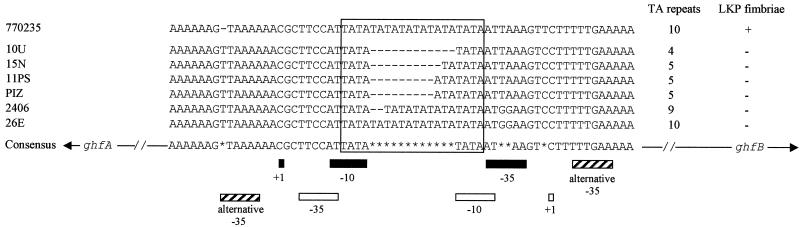

We studied the region between the ghfA and ghfB genes, which is supposed to include the ghf cluster promoters, by PCR with primers HA1251 and HB2157rc (Table 1), designed from the sequences of the hifA and hifB genes that surround the promoter region in Hib strain 770235 (32). Fragments of about 500 bp were amplified for the six genital strains possessing hif-like genes, and a fragment of about 900 bp was obtained for strain 770235 (Fig. 3). DNA sequencing showed that this difference in size was due to the presence in strain 770235 of 10 repeats of a palindromic sequence of 44 or 45 nucleotides, composed of noncoding DNA. These repeats are located upstream of hifB, between the hifB transcription start site and the ATG initiation codon for hifB. These repeats are thus contained on the transcript but are not translated. In the genital strains, the nucleotide sequence between the ghfA and ghfB ORFs comprised 376 to 389 bp. It included the ghfA and the ghfBCDE promoters (Fig. 4), which were divergent and overlapped in a zone including the −10 and −35 sequences of both promoters, separated by a string of TA dinucleotide repeats: strains 2406 and 26E had 9 and 10 repeats, respectively; strains 10U and 15N had only 4 and 5 repeats, respectively; and strains 11PS and PIZ had 5 TA repeats with an additional A. No difference in the number of TA repeats was observed before and after the LKP fimbria-enrichment procedure.

FIG. 3.

PCR products of the intergenic regions between ghfA and ghfB and between hifA and hifB obtained with primers HA1251 and HB2157rc for genital cryptic Haemophilus strains 15N, 10U, 11PS, 26E, PIZ, and 2406 (lanes 2 to 7) and the Hib control strain, 770235 (lane 9). No amplification was observed for the genital cryptic Haemophilus strain 16N, which lacks hif and ghf genes (lane 8). Lane 1, 1-kb ladder; lane 10, 100-bp ladder. The sizes of the PCR fragments are indicated on the right.

FIG. 4.

Alignment of the nucleotide sequences of the two overlapping promoters of the hif gene cluster of Hib strain 770235 and of the ghf gene clusters of the genital cryptic Haemophilus strains 10U, 15N, 11PS, PIZ, 2406, and 26E. The dashes correspond to missing nucleotides. The −35 and −10 sequences and the sites of initiation of transcription (+1) are indicated below the sequences by solid boxes for the promoters of ghfA and hifA genes and by open boxes for the promoters of the other ghf and hif genes. The alternative −35 boxes of strains 15N, 11PS, and PIZ are indicated by hatched boxes. The frame delimits the TA repeats between the −10 and −35 sequences. In the consensus sequence, the arrows indicate the direction of transcription and the asterisks indicate sequence differences. +, present; −, absent.

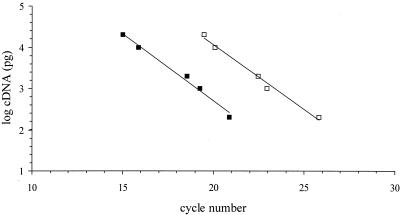

We investigated whether the ghfA and ghfB genes were transcribed by performing RT-PCR with total cellular RNA extracted from the genital cryptic Haemophilus strains and from the Hib control strain, 770235, in mid-log-phase growth (Fig. 5). As a positive control for RT-PCR, we carried out an amplification reaction with the products of RT and primers HCRY164 (5′ ATTAAAGTGTGGGACCTTCG 3′) and HCRY445 (5′ TGTACTATTAGCACACATCC 3′), which are specific for the rRNA genes of the genital genospecies (23). As expected, a PCR product was obtained with the cDNAs from all genital strains but not with the cDNA of the Hib strain 770235 (Fig. 5B). With primers GB92 and GB446rc, internal to the hifB and ghfB genes, an amplicon was obtained with the cDNA of the Hib control strain, 770235; with the cDNAs of four genital strains (26E, PIZ, 11PS, and 15N); and with the genomic DNAs of all strains used as controls (Fig. 5A). Identical results were obtained using primers HA654 and HA1310rc, internal to the hifA and ghfA genes (data not shown). We checked that extracted RNA was not contaminated by DNA by performing PCR with the three sets of primers, using the RNAs of all strains as a template, in the absence of reverse transcriptase; no amplification product was obtained. To compare the stabilities of the mRNAs from the genital strain 26E and from Hib strain 770235, we used fluorescence-based real-time PCR to quantify cDNAs from these two strains. Dilutions of cDNA from Hib strain 770235 were used to generate standard curves with each primer set (Fig. 6). The Ct values for genital strain 26E were then compared with the calibrator Ct values. cDNA from strain 16N, which lacks the ghf and hif genes, was used as a negative control. With primers GA36 and GA122rc, which are specific to ghfA and hifA, the Ct values of strains 26E and 770235 were very similar (Table 2), indicating that the amounts of cDNA corresponding to these genes are similar for the two strains. With primers GB92 and GB177rc, which are specific to ghfB and hifB, the Ct value was higher for strain 26E than for strain 770235 (Table 2). The standard curve showed that strain 26E contained five times less cDNA for this gene than did the Hib strain. As expected, no amplification product was obtained with the cDNA from the genital strain 16N with either primer set.

FIG. 5.

(A) PCR products for ghfB and hifB genes obtained with cDNA from genital cryptic Haemophilus strains 15N, 10U, 11PS, 26E, 2406, and PIZ (lanes 1 to 6) and cDNA and DNA from the Hib positive-control strain, 770235 (lanes 9 and 11). As a negative control, PCR was performed with RNAs of strains 26E, PIZ, and 770235 (lanes 7, 8, and 10) incubated as for RT-PCR but in the absence of reverse transcriptase. Lanes M, 100-bp ladders. (B) As a control for RT-PCR, 16S rDNA from genital cryptic Haemophilus was amplified with cDNAs from genital strains 15N, 10U, 11PS, 26E, 2406, and PIZ (lanes 1 to 6) and with cDNA from Hib strain 770235 (lane 7). As a negative control, PCR was performed with RT products obtained in the absence of reverse transcriptase from the same strains (lanes 9 to 15) and with no template (lanes 8 and 16). Lanes M, 100-bp ladders.

FIG. 6.

Standard curves generated from Ct values obtained by real-time PCR with dilutions of cDNA (20, 10, 2, 1, and 0.2 ng) of Hib strain 770235. The Ct values are indicated by solid squares for real-time PCR performed with primers GA36 and GA122rc, specific to ghfA and hifA, and by open squares for PCR with primers GB92 and GB177rc, specific to ghfB and hifB.

TABLE 2.

Threshold cycle values obtained by real-time PCR for ghfA and hifA genes and for ghfB and hifB genes

| Strain | Quantity of cDNA used as template (ng) | Cta values obtained with primers:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| GA36 and GA122rc | GB92 and GB177rc | ||

| 770235 | 20 | 15.02 | 19.51 |

| 770235 | 10 | 15.87 | 20.09 |

| 770235 | 2 | 18.56 | 22.45 |

| 770235 | 1 | 19.27 | 22.96 |

| 770235 | 0.2 | 20.88 | 25.81 |

| 26E | 20 | 15.47 | 21.04 |

| 16N | 20 | -b | - |

Ct is defined as the point at which the fluorescent signal is first recorded as statistically significant above background. The more cDNA present at the beginning of the reaction, the fewer cycles it takes to reach this point.

A dash indicates that no signal was obtained after 30 cycles of amplification.

Junctions of the pilus gene cluster.

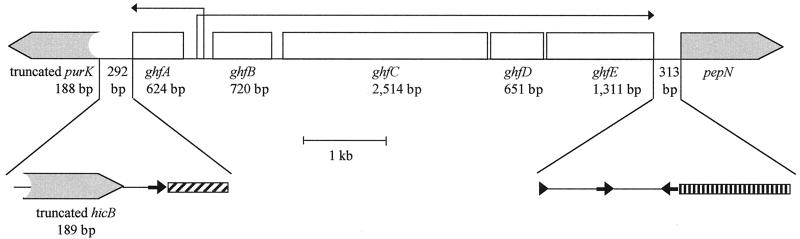

For the genital strains, no amplicon was obtained with primer PURE451, used with primer GA499 or PEPN7717rc (Table 1). Identical results were obtained with seven different primers designed from the sequences of the purE genes of strains Rd and 770235 (7, 32), suggesting that purE is not the 5′ gene bordering the ghf cluster in the genital strains. New primers were designed corresponding to purK, the gene adjacent to purE in H. influenzae (7). With the PURK1071-PEPN7717rc primer set, the amplicon obtained was about 7 kb in size for the six genital strains and about 8.5 kb for Hib strain 770235 (data not shown). The sequence of the 650-bp amplicons obtained from the genital strains with the PURK1071-GA499 primer set confirmed that a fragment of about 1.4 kb found at the 5′ end of the hif cluster in strain 770235 was absent from all of the genital strains. The missing sequence included the purE gene and most of the adjacent purK gene (Fig. 7). The intergenic sequence between purK and ghfA comprised 292 bp and was strictly identical for the six genital strains. It included three sequences homologous to sequences described at the 5′ junction of hif clusters in several strains of H. influenzae: a 189-bp copy of hicB with a 5′ deletion, a 46-bp sequence homologous to the conserved junction sequences of strains GA2078 and F3031, and a 21-bp sequence homologous to the intergenic dyad sequence (IDS) described by Geluk et al., Mhlanga-Mutangadura et al., and Read et al. (8, 15, 25).

FIG. 7.

Genital Haemophilus LKP-like cluster. The shaded boxes represent nonfimbrial genes, and the open boxes represent fimbrial genes. The long thin arrows show the directions of transcription from the two overlapping promoters. Flanking the ghf cluster, the vertically hatched bar indicates a 133-bp direct repeat including the regulatory region of the pur operon, and the diagonally hatched bar indicates a 46-bp conserved junction sequence. The thick arrows indicate 21-bp repeated sequences (IDSs). The directions of the arrows indicate their orientations. The arrowhead indicates a truncated IDS. The ghf genes are drawn to scale.

The nucleotide sequences between the 3′ end of the ghf cluster and the bordering gene were determined by sequencing the PEPN7717rc-GE1249 amplification products. The sequences of the six genital strains were strictly identical. ghfE was separated from pepN by a 313-bp sequence including, as shown in Fig. 7, two complete IDSs, one incomplete IDS, and a 133-bp sequence homologous to the extended direct-repeat sequence previously described in several Haemophilus strains, which includes the pur regulatory region (purR box) (8, 15, 25, 32).

DISCUSSION

In a previous study, we described three genes, ghfA, ghfD, and ghfE, encoding the major and two minor fimbrial proteins and belonging to the ghf fimbrial gene cluster, which were present in six piliated genital strains of Haemophilus (9). In this work, we characterized in these six strains the remaining two fimbrial genes, ghfB and ghfC. Their nucleotide sequences were at least 93% identical to those of the LKP fimbrial genes hifB and hifC described in Hib, NTHi, and Hi biogroup aegyptius strains (24, 32, 34), with no clear major difference. These results suggest that ghfB and ghfC may encode efficient chaperone and platform assembly proteins, which are involved in the assembly of pili in these genital strains of Haemophilus. Southern blots for the genes ghfB (this work), ghfA, ghfD, and ghfE (9) showed hybridization of a single band for each gene and were thus consistent with the presence of a unique LKP-like fimbrial gene cluster.

In all genital strains studied, the general organization of the coding regions of the ghf cluster was well conserved and similar to that of the hif cluster. All five LKP-like genes (ghfA to ghfE) required for pilus biogenesis were present on the chromosomes of the six strains, and their homology with the five hif genes suggested that they were probably functional. However, hemagglutination properties and ultrastructural studies demonstrated that although fimbriae were present in the six strains, none were of the LKP type. The findings of a recent study by Clemans et al. are consistent with this observation. Despite the presence of hifA and hifE genes in six biotype IV NTHi strains from genital and neonatal specimens, none of the strains expressed the corresponding proteins and no hemagglutinating fimbriae were observed by these authors (5). The primary amino acid sequence of the GhfE protein (9) was 51 to 59% identical to those of various HifE putative pilus tip adhesins of H. influenzae (14, 26). The identity was stronger in the C-terminal one-third implicated in chaperone binding, and the three short highly conserved domains which are thought to be implicated in adhesion to mammalian cells were also conserved in the N-terminal half of GhfE. Thus, it is unlikely that the inability of fimbriae from genital strains to cause hemagglutination is related to the primary amino acid sequence of GhfE. Nevertheless, as the sequence of the binding pocket of the adhesin and the sequence responsible for the integration of HifE into the mature pilus have not been clearly identified, we cannot exclude the possibility that the differences between GhfE and HifE modify the adhesion properties.

In the LKP fimbrial gene cluster of Haemophilus, there are no separate genes regulating fimbria expression. Transcription is therefore purely dependent on the promoter region located between the hifA and hifB genes (32). The major alterations of the intergenic ghfA-ghfB region observed in the genital strains may account for the absence of LKP fimbria expression. It has been shown in Hib and NTHi strains that LKP fimbria expression depends on the number of TA repeats constituting the region of overlap between the promoters of the divergently transcribed hifA and hifBCDE genes. Transcription was optimal when 10 TA repeats were spacing the −10 and −35 boxes of the two promoters. The level of transcription was lower if there were 11 or 12 repeats, and transcription was totally inhibited if there were 9 or 4 repeats (8, 24, 31). As expected, RNA transcripts were detected for the fimbrial genes ghfA and ghfB for the only genital strain possessing 10 TA repeats, and no ghf transcripts were detected for the two strains possessing 4 or 9 TA repeats. Surprisingly, we obtained ghf transcripts for the three genital strains possessing only five TA repeats or the sequence TATAATATATA. Closer examination of the nucleotide sequences revealed putative alternative −35 boxes on each strand (TTCAAA and TTAAAA) for these three strains (Fig. 4). These −35 boxes were found 17, 18, and 19 bp upstream of the −10 promoter sequences, with 4 nucleotides of 6 matching the consensus nucleotide sequence of E. coli promoters (10), thus fulfilling all the conditions for this region to form ghfA and ghfBCDE functional promoters.

van Ham et al. demonstrated that LKP fimbria expression was also related to the presence of multiple (10 or 11) adjacent repeats of 44- or 45-nucleotide palindromic sequences upstream of hifB. These sequences, which are transcribed but not translated, create a large number of secondary structures at the 5′ end of mRNA due to the formation of successive hairpins. These hairpins probably stabilize the large (5.3-kb) and particularly unstable transcript of the hifB, hifC, hifD, and hifE genes, ensuring that it is expressed before the rapid degradation of the mRNA occurs (31, 32). We showed that the Hib strain 770235 contains less hifB mRNA than hifA mRNA (Table 2), thus confirming that this large transcript is naturally unstable. The length of the region between the ghfB gene and its promoter, identical for all genital strains, was 430 bp shorter than that of Hib strain 770235 due to the absence of 10 of the 44- or 45-nucleotide-long repetitive palindromic extragenic sequences. We showed that strains 26E and Hib 770235 contain similar amounts of hifA and ghfA mRNA but five times less ghfB than hifB mRNA. These results suggest that although ghf genes are transcribed in some strains, the 430-bp deletion induces an increased instability of mRNA that prevents gene expression.

At both ends of the cluster, we found short inverted repeats homologous to those described as IDSs (25), repetitive extragenic palindromic sequences (15), or short inverted sequences (8). As suggested for hif clusters of various Haemophilus strains, the ghf gene cluster may initially have been present on a mobile element that was inserted into the chromosome, using the short inverted repeats as a site of recombination. The gene bordering the ghf cluster on the 3′ side was pepN, and the 3′ flanking region of the ghf cluster included conserved sequences such as IDS and the purR box, as previously described in various Haemophilus strains (8, 15, 25, 32). The 5′ junction of the ghf cluster was identical for all genital strains, contrasting with the marked diversity reported for sequences flanking the 5′ end of the hif cluster of H. influenzae strains (8, 15, 25). These results again demonstrate considerable homogeneity within this particular group of genital strains. At the 5′ end of the cluster, we observed an unusual feature that has never before been described: the absence of the purR box, of the whole purE gene, and of most of purK, the adjacent gene on the 5′ side. Mhlanga-Mutangadura et al. suggested that a hypothetical Haemophilus progenitor strain acquired, by horizontal transfer, the extended LKP fimbrial gene cluster between purE and pepN genes, including a purR box, and the two hif-contiguous ORFs hicA and hicB at the 5′ junction of the gene cluster. Various deletions then occurred, leading to variants with partial or total hif deletions (15). According to this model, it may be supposed that purK, purE, and the purR box were initially present in genital strains but were then eliminated by a large deletion so that only the five ghf genes and part of hicB remained.

In conclusion, the ghf cluster described here in six genital Haemophilus strains was probably initially present on a mobile element and is similar to the hif clusters for LKP fimbriae of H. influenzae. The remarkable identity of the coding and noncoding sequences of the six strains, including the 3′ and 5′ flanking regions of the ghf cluster, contrasts with the diversity of several regions in hif clusters. We describe a new feature consisting of the truncation of a 1.4-kb fragment at the 5′ cluster junction. The results obtained suggest that although the five hif-like genes of the ghf cluster are present and complete, no genital strain of Haemophilus produces LKP fimbriae, probably due to the major alterations observed in the intergenic ghfA-ghfB region, which includes the promoters. Therefore, other genes remain to be identified to account for the piliation observed by electron microscopy on genital Haemophilus strains possessing or not possessing LKP-like fimbrial genes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pierre-Yves Sizaret for electron microscopy.

Editor: V. J. DiRita

REFERENCES

- 1.Albritton, W. L., J. L. Brunton, M. Meier, M. N. Bowman, and L. A. Slaney. 1982. Haemophilus influenzae: comparison of respiratory tract isolates with genitourinary tract isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 16:826-831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen, B. L., G. F. Gerlach, and S. Clegg. 1991. Nucleotide sequence and functions of mrk determinants necessary for expression of type 3 fimbriae in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 173:916-920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakaletz, L. O., B. M. Tallan, T. Hoepf, T. F. DeMaria, H. G. Birck, and D. J. Lim. 1988. Frequency of fimbriation of nontypable Haemophilus influenzae and its ability to adhere to chinchilla and human respiratory epithelium. Infect. Immun. 56:331-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brinton, C. C., Jr., M. J. Carter, D. B. Derber, S. Kar, J. A. Kramarik, A. C. C. To, S. C. M. To, and S. W. Wood. 1989. Design and development of pilus vaccines for Haemophilus influenzae diseases. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 8:S54-S61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clemans, D. L., C. F. Marrs, R. J. Bauer, M. Patel, and J. R. Gilsdorf. 2001. Analysis of pilus adhesins from Haemophilus influenzae biotype IV strains. Infect. Immun. 69:7010-7019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connor, E. M., and M. R. Loeb. 1983. A hemadsorption method for detection of colonies of Haemophilus influenzae type b expressing fimbriae. J. Infect. Dis. 148:855-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleischmann, R. D., M. D. Adams, O. White, R. A. Clayton, E. F. Kirkness, A. R. Kerlavage, C. J. Bult, J.-F. Tomb, B. A. Dougherty, J. M. Merrick, K. McKenney, G. Sutton, W. FitzHugh, C. Fields, J. D. Gocayne, J. Scott, R. Shirley, L.-I. Liu, A. Glodek, J. M. Kelley, J. F. Weidman, C. A. Phillips, T. Spriggs, E. Hedblom, M. D. Cotton, T. R. Utterback, M. C. Hanna, D. T. Nguyen, D. M. Saudek, R. C. Brandon, L. D. Fine, J. L. Fritchman, J. L. Fuhrmann, N. S. M. Geoghagen, C. L. Gnehm, L. A. McDonald, K. V. Small, C. M. Fraser, H. O. Smith, and J. C. Venter. 1995. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science 269:496-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geluk, F., P. P. Eijk, S. M. van Ham, H. M. Jansen, and L. van Alphen. 1998. The fimbria gene cluster of nonencapsulated Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Immun. 66:406-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gousset, N., A. Rosenau, P. Y. Sizaret, and R. Quentin. 1999. Nucleotide sequences of genes coding for fimbrial proteins in a cryptic genospecies of Haemophilus spp. isolated from neonatal and genital tract infections. Infect. Immun. 67:8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawley, D. K., and W. R. McClure. 1983. Compilation and analysis of Escherichia coli promoter DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:2237-2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klemm, P., and G. Christiansen. 1990. The fimD gene required for cell surface localization of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbriae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 220:334-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krogfelt, K. A. 1991. Bacterial adhesion: genetics, biogenesis, and role in pathogenesis of fimbrial adhesins of Escherichia coli. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13:721-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Locht, C., M. C. Geoffroy, and G. Renauld. 1992. Common accessory genes for the Bordetella pertussis filamentous hemagglutinin and fimbriae share sequence similarities with the papC and papD gene families. EMBO J. 11:3175-3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCrea, K. W., J. L. St. Sauver, C. F. Marrs, D. Clemans, and J. R. Gilsdorf. 1998. Immunologic and structural relationships of the minor pilus subunits among Haemophilus influenzae isolates. Infect. Immun. 66:4788-4796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mhlanga-Mutangadura, T., G. Morlin, A. L. Smith, A. Eisenstark, and M. Golomb. 1998. Evolution of the major pilus gene cluster of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 180:4693-4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy, T. F., C. Kirkham, and D. J. Sikkema. 1992. Neonatal, urogenital isolates of biotype 4 nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae express a variant P6 outer membrane protein molecule. Infect. Immun. 60:2016-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musser, J. M., S. J. Barenkamp, D. M. Granoff, and R. K. Selander. 1986. Genetic relationships of serologically nontypable and serotype b strains of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Immun. 52:183-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pichichero, M. E. 1984. Adherence of Haemophilus influenzae to human buccal and pharyngeal epithelial cells: relationship to piliation. J. Med. Microbiol. 18:107-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quentin, R., A. Goudeau, E. Burfin, G. Pinon, C. Berger, J. Laugier, and J. H. Soutoul. 1987. Infections materno-foetales à Haemophilus influenzae. Press. Med. 16:1181-1184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quentin, R., A. Goudeau, R. J. Wallace, Jr., A. L. Smith, R. K. Selander, and J. M. Musser. 1990. Urogenital, maternal and neonatal isolates of Haemophilus influenzae: identification of unusually virulent serologically non-typable clone families and evidence for a new Haemophilus species. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136:1203-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quentin, R., C. Martin, J. M. Musser, N. Pasquier-Picard, and A. Goudeau. 1993. Genetic characterization of a cryptic genospecies of Haemophilus causing urogenital and neonatal infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:1111-1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quentin, R., J. M. Musser, M. Mellouet, P. Y. Sizaret, R. K. Selander, and A. Goudeau. 1989. Typing of urogenital, maternal, and neonatal isolates of Haemophilus influenzae and Haemophilus parainfluenzae in correlation with clinical source of isolation and evidence for a genital specificity of H. influenzae biotype IV. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:2286-2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quentin, R., R. Ruimy, A. Rosenau, J. M. Musser, and R. Christen. 1996. Genetic identification of cryptic genospecies of Haemophilus causing urogenital and neonatal infections by PCR using specific primers targeting genes coding for 16S rRNA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1380-1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Read, T. D., M. Dowdell, S. W. Satola, and M. M. Farley. 1996. Duplication of pilus gene complexes of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius. J. Bacteriol. 178:6564-6570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Read, T. D., S. W. Satola, and M. M. Farley. 2000. Nucleotide sequence analysis of hypervariable junctions of Haemophilus influenzae pilus gene clusters. Infect. Immun. 68:6896-6902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Read, T. D., S. W. Satola, J. A. Opdyke, and M. M. Farley. 1998. Copy number of pilus gene clusters in Haemophilus influenzae and variation in the hifE pilin gene. Infect. Immun. 66:1622-1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenau, A., P. Y. Sizaret, J. M. Musser, A. Goudeau, and R. Quentin. 1993. Adherence to human cells of a cryptic Haemophilus genospecies responsible for genital and neonatal infections. Infect. Immun. 61:4112-4118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sirakova, T., P. E. Kolattukudy, D. Murwin, J. Billy, E. Leake, D. Lim, T. DeMaria, and L. Bakaletz. 1994. Role of fimbriae expressed by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in pathogenesis of and protection against otitis media and relatedness of the fimbrin subunit to outer membrane protein A. Infect. Immun. 62:2002-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Summers, W. C. 1970. A simple method for extraction of RNA from E. coli utilizing diethylpyrocarbonate. Anal. Biochem. 33:459-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turk, D. C. 1984. The pathogenicity of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Med. Microbiol. 18:1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Ham, S. M., L. van Alphen, F. R. Mooi, and J. P. M. van Putten. 1993. Phase variation of H. influenzae fimbriae: transcriptional control of two divergent genes through a variable combined promoter region. Cell 73:1187-1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Ham, S. M., L. van Alphen, F. R. Mooi, and J. P. M. van Putten. 1994. The fimbrial gene cluster of Haemophilus influenzae type b. Mol. Microbiol. 13:673-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallace, R. J., C. J. Baker, F. J. Quinones, D. G. Hollis, R. E. Weaver, and K. Wiss. 1983. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (biotype 4) as a neonatal, maternal, and genital pathogen. Rev. Infect. Dis. 5:123-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watson, W. J., J. R. Gilsdorf, M. A. Tucci, K. W. McCrea, L. J. Forney, and C. F. Marrs. 1994. Identification of a gene essential for piliation in Haemophilus influenzae type b with homology to the pilus assembly platform genes of gram-negative bacteria. Infect. Immun. 62:468-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu, H. C. 1986. Proteolytic processing of signal peptides, p. 33-59. In A. W. Strauss, I. Boime, and G. Kreil (ed.), Protein compartmentalization. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y.