Abstract

Purpose

We determined the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) characteristics of normal clitoral anatomy.

Materials and Methods

A series of MRI studies of 10 healthy, nulliparous volunteers with no prior surgery and normal pelvic examination was studied and the key characteristics of clitoral anatomy were determined. A range of different magnetic resonance sequences was used without any contrast agent.

Results

The axial plane best revealed the clitoral body and its proximal continuation as the paired crura. The glans was seen more caudal than the body of the clitoris. The bulbs of the clitoris had the same signal as the rest of the clitoris in the axial plane and they related consistently to the other erectile structures. The bulbs, body and crura formed an erectile tissue cluster, namely the clitoris. In turn, the clitoris partially surrounded the urethra and vagina, forming a consistently observed tissue complex. Midline sagittal section revealed the shape of the body, although in this plane the rest of the clitoris was poorly displayed. The coronal plane revealed the relationship between the clitoral body and labia. The axial section cephalad to the clitoral body best revealed the vascular component of the neurovascular bundle to the clitoris. The fat saturation sequence particularly highlighted clitoral anatomy in healthy, premenopausal, nulliparous women.

Conclusions

Normal clitoral anatomy has been clearly demonstrated using noncontrast pelvic MRI.

Keywords: clitoris, magnetic resonance imaging, anatomy, premenopause, parity

Although there has been some recent progress, advances in understanding male sexual function and dysfunction have not been paralleled by similar advances in female sexual function, even in basic anatomy and physiology. A problem facing researchers in female sexuality is the fact that the clitoris is largely an internal structure relative to the external visibility of the penis. Clitoral anatomy based on cadaveric studies have been limited by the lack of access to younger specimens with most being from elderly, postmenopausal women in whom erectile structures were distorted by the absence of blood flow and by the embalming process.

Suh et al described detailed imagery of female genital anatomy using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with the blood pool contrast medium MS-325.1 Visualization was poor or absent on T1-weighted images prior to contrast medium use. Two other reports from the same center indicated that this is useful for evaluating female sexual arousal.2, 3 However, there is no comment on MRI obtained by the fat saturation technique and planes other than the axial plane are not provided. Prior studies also involved women in whom parity status was unknown. We present findings in a series of healthy, premenopausal, nulliparous volunteers and describe clitoral anatomy as seen in each plane using unenhanced MRI. Dissection studies revealed significant age related atrophy, and so we expected that clitoral tissues of premenopausal women would be more easily distinguished with MRI than would tissues from an unselected group of women.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An institutional review board approved MRI study was commenced at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor in 1994. This prospective study involved the MRI evaluation of 240 patients, specifically to evaluate the effects of a first birth. Among these women were a consecutive series of 10 healthy, nulliparous, premenopausal volunteers with no prior surgery and no abnormality on pelvic examination. They underwent several MRI sequences to test which of them best showed the pelvic floor structures. These scans form the basis of this study.

Scanning techniques included T2-weighted fast spin-echo (FSE), T1-weighted spin-echo and proton density FSE with or without fat saturation. A 1.5 Tesla magnet machine was used to create the images. For most scans 0.4 cm section thickness with a 1.0 cm space between sections and a matrix size of 256 × 256 were used. Each scan was first examined to determine the features present in each plane (axial, coronal and sagittal) with each type of scanning. In a few series 1.0 cm sections were used and the sections omitted anatomical detail. For the purpose of clarifying clitoral anatomy only images using 0.4 cm section thickness are shown. All scans were then reexamined to determine the consistency with each of the features identified. The consistent findings are detailed. Structure identification was based on our previous published cadaver studies.4

Prior to analysis all images were converted into digital files masking identifying features (name and date of birth) of the individual. No other modification of the images was made.

RESULTS

Clitoral anatomy was shown most clearly in the axial plane. The sagittal and coronal planes provided further details and they were complementary. Ultimately all components of the clitoris, crura, corpora, bulbs, glans and its neurovascular bundle could be clearly identified on MRI after the combination of the 3 planes was used. Each plane provided a different representation of the structure.

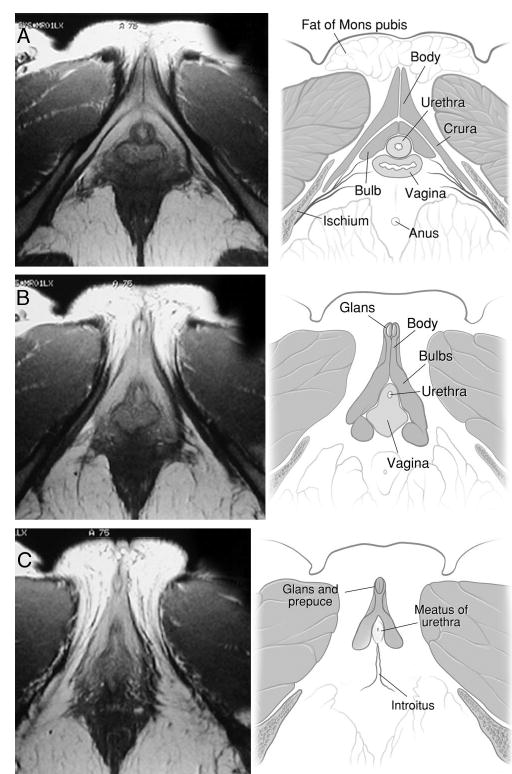

Figure 1, A shows a typical axial proton density scan without fat saturation. The clitoris is ventral to the urethra and vagina. Its body projects into the fat of the mons pubis. It is composed of 5 components, namely the paired corpora united in the midline and separated only by a fibrous septum, the bilateral (vestibular) bulbs and the single glans. The glans is a more caudal structure and, therefore, it was seen in more caudal sections (fig. 1, B and C). The corpora diverge and follow the pubic rami on each side, where they are called the crura. The clitoris is distinct from the urethra and vagina. In figure 1, A the target-like appearance of the urethra is particularly distinct with the urethral wall having a darker gray color than the surrounding clitoris. The bulbs flank the urethra and vagina laterally. This axial section lies directly caudal to the symphysis pubis. The fat in this sequence is the whitest structure, followed by the cavernous tissue of the clitoris, the urethral lumen, the vaginal wall, the urethral wall and finally muscle in decreasing order of intensity. Dorsally the clitoris, urethra and vagina are related to the ischiorectal fat and in the midline they are related to the anal canal. The body of the clitoris is an angled structure that projects inferiorly into the mons pubis fat with its most caudal part continuous with the glans clitoris. Figure 1, B shows an axial section 1.0 cm caudal to the figure 1, A section. Because of the shape of the clitoris, the glans is typically seen in a more caudal axial section than the rest of the clitoris. In this woman the glans is seen in 2 sections (fig. 1, B and C). In the more caudal sections the urethra and vagina are not distinct and the caudal limit of the bulbs is just visible lateral to the urethra. The glans is the most distinct clitoral structure in these sections. In some women the urethral meatus was also distinct in the most caudal section.

Fig. 1.

A, clitoris and its components, including bulbs, crura and corpora, are well demonstrated in axial plane. These structures lie ventral and lateral to urethra and vagina as cluster or complex. MRI specifications for this scan were FSE, TR:4000, TE:15/Ef, EC:1/1 16kHz, FOV: 16x16, 4.0thk/1.0sp, 30/04:16, 256x256/2 NEX, FCs/NP. B and C, next 2 sections caudal to section A in same volunteer. B, clitoral glans ventral to remainder of clitoris. Its midline septum and prepuce are evident. C, most caudal section reveals glans and caudal limit of urethra (urethral meatus), clitoral bulbs and vagina (introitus). In this perineal section clitoral body and crura are not present and urethral meatus and vaginal introitus are not distinct. MRI specifications were FSE, TR:4000, TE:15/Ef, EC:1/1 16kHz, FOV:16x16, 4.0thk/1.0sp, 30/04:16, 256x256/2 NEX, FCs/NP.

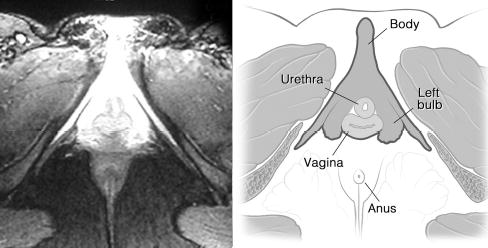

The cavernous or erectile tissue was highlighted using a fat saturation technique. In this type of scan the fat appeared black and the cavernous structures of the clitoris were bright white (fig. 2). The urethral wall and vagina were also highlighted with this technique, although to a lesser extent than cavernous tissue. Other surrounding tissues, muscle and bone appeared as dark structures, increasing the contrast with the centrally placed cavernous structures. In axial section the clitoris formed a triangular complex with the urethra and vagina, namely the clitorourethrovaginal complex.

Fig. 2.

Using fat saturation highlighted cavernous tissue of clitoris surrounding urethra and vagina, while other structures appeared gray or black. Triangular clitorourethrovaginal complex was clearly seen using this sequence. MRI specifications were FSEIR, TR:4083, TE:22/Ef, EC:1/1 31.2kHz, TI:165, FOV20x20, 6.0thk/1.5sp, 15/06: 32, 256x192/4 NEX, NP/VB/SQ/SPF.

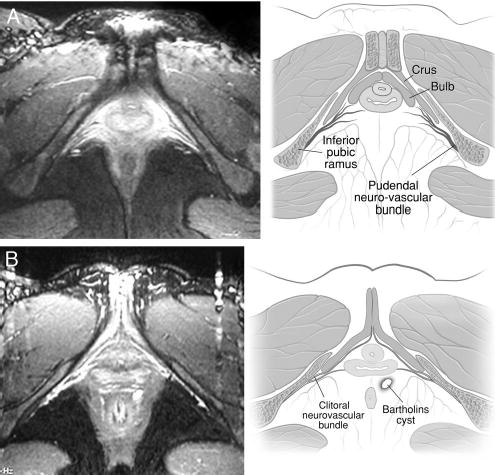

In figure 3, A the structures best seen are the vessels of the neurovascular bundles arising from the pelvic side wall, where the terminal component of the pudendal neurovascular bundle bifurcates into perineal and clitoral divisions to supply the clitorourethrovaginal complex. The perineal division is also best seen in figure 3, A, while the clitoral division, which ascends along the inferior pubic ramus adjacent to the crura, is best seen in figure 3, B. The neurovascular bundle is cranial to the clitoral body. The autonomic cavernous neurovascular supply to the clitoris is not visible on these MRI studies. The large clitoral neurovascular bundles on either side ascend along the ischiopubic ramus to the under surface of the pubic symphysis in the midline, from which they run along the cephalad surface of the clitoral body toward the glans. These bundles, which were easily seen using dissection techniques, were not large enough to be visible consistently on MRI, although fat saturation is known to highlight the vascular structures.

Fig. 3.

A, this axial section cephalad to image shown in figures 1 and 2 reveals divisions of pudendal neurovascular bundle (clitoral and perineal neurovascular bundles) supplying complex. Vascular structures of bundle and cavernous tissue are highlighted by fat saturation. Nerves are not shown by MRI but they are known from dissections to accompany vessels. B, another fat saturated section cephalad to clitoris highlights clitoral veins draining into pudendal neurovascular bundle attaching to pelvic side wall.

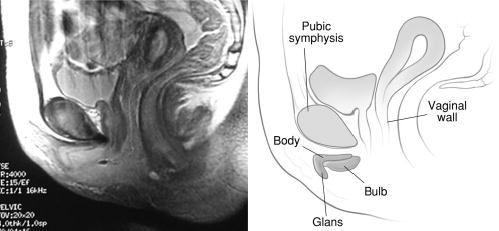

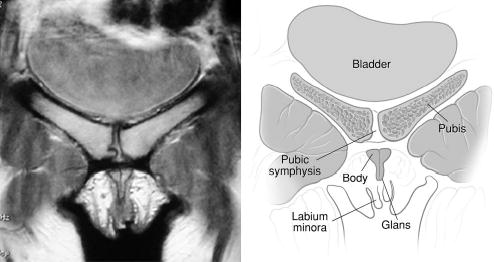

Sagittal scans demonstrated the angled clitoral body and glans projecting into the mons on the under surface of the symphysis pubis (fig. 4). The bulbs and crura were also visible in more lateral sections, although not well displayed. Coronal sections revealed the 2 corpora forming the body and ending as the glans clitoris (fig. 5). The body was seen attached to the under surface of the symphysis pubis. The labia minora and majora were well seen in this coronal section. The glans is visible extending more dorsal toward the anus because of its tendency to curve dorsal and caudal.

Fig. 4.

This midline sagittal section highlights almost boomerang-like appearance of clitoral body, crura and glans. MRI specifications were FSE, TR:4000, TE:15/Ef, EC:1/1 16kHz, FOV: 20x20, 4.0thk/1.0sp, 30/04:16, 256x256/2 NEX, FCf/NP.

Fig. 5.

Coronal section reveals paired clitoral corpora comprising clitoral body, located caudal to pubic symphysis. Caudal limit of body is glans. Relationship between glans and labia is seen. MRI specifications were FSE, TR:4000, TE:15/Ef, EC:1/1 16kHz, FOV:16x16, 4.0thk/1.0sp, 30/04:16, 256x256/2 NEX, FCf/NP.

Bulbar anatomy is best displayed in axial views and it was seen to a limited extent in sagittal and coronal views in all women. The bulbs met ventral to the urethra. Dissection studies have shown that they are not continuous across the midline.4 They descend on either side of the urethra and flank the lateral aspect of the distal vaginal wall bilaterally.4 The bulbs have a more consistent relationship with the clitoris and urethra than with the vestibule. Thus, in this study the bulbs are named the bulbs of the clitoris according to their consistent relationship to the clitoris.

DISCUSSION

MRI studies of the clitoris complement studies previously performed in cadavers4 and reveal the anatomy in healthy, premenopausal nullipara. No major differences were apparent between findings in the cadavers and on MRI, although in cadavers the structures appeared to be atrophic, as would be expected because of the advanced age of most specimens and other reasons.

Historical, social and scientific factors appear to be responsible for the poor presentation of clitoral anatomy even in current textbooks. Active deletion of the clitoris as a labeled structure from an early version of Gray’s Anatomy compared with subsequent versions indicates the influence of social factors over science.5 The medical profession has also had a major influence on female sexuality throughout history, particularly in the 19th century. The widespread practice in Western medicine of clitoridectomy for indications as diverse as epilepsy, hysteria and catalepsy is relatively recent.6 In addition to such factors, anatomists have compounded the poor display of clitoral anatomy by revealing it only in 1 plane. While the sagittal plane may suit the display of an essentially linear structure such as the penis, the clitoris is not well displayed in this plane. The axial plane is the most useful. As a multiplanar modality, MRI reveals each component of the clitoris and complements the information obtained at dissection.

This MRI study of the clitoris revealed each clitoral component in detail. The advantages of MRI over dissection based study are that it reveals anatomy in the living subject and it has the ability to enhance a given tissue because of its relative response to magnetic resonance. The MRI technique of fat saturation enhances cavernous tissue, of which the clitoris is composed. Fat saturation gives each clitoral structure a white appearance juxtaposed to all related structures, which are a shade of gray. Even the urethra and vagina, which are vascular structures, appear relatively gray by comparison to the clitoris. This indicates the highly vascular nature of the clitoris even in the nonaroused state.

Recent research has shown that MRI is capable of demonstrating vascular enhancement that may correlate with female sexual arousal, thereby, showing great promise for sexual function studies.1–3 The new, gadolinium based, blood pool contrast agent MS-325 administered intravenously has been found to provide an excellent depiction of the female genitalia in premenopausal and postmenopausal women.1 The same agent has been shown to be useful in studying changes in female genitalia that occur with sexual arousal. The exact superiority of this contrast enhanced, T1-weighted study over the unenhanced fat saturation technique is not clear. MRI with phased array pelvic and endorectal coils has been shown to be an excellent tool for studying the female urethra and periurethral diseases.7

Objective imaging techniques such as MRI and even photography help overcome the inaccuracies associated with diagrams. The structures least well described in anatomical textbooks to date are the bulbs. Typically their relationship to the clitoris and urethra is not acknowledged or in fact said not to exist.8 When depicted, the bulbs are usually drawn as if they pass alongside the vaginal introitus, forming the core of the labia. MRI clearly shows the extensive relationship between the urethra and bulbs, and also reveals how these structures are intimately related to the crura and corpora forming the root of the clitoris, an anatomical structure mentioned in some recent anatomical textbooks.9 The view of the bulbs afforded by MRI shows even more clearly than with dissection that the bulbs on either side continue anterior to the urethra and meet together in the midline without merging. The exact role of the bulbs in urethral support and sexual function is unclear. Recent study has suggested they have a significant role in urethral continence.10 The concept of the clitorourethrovaginal complex is not new, having been called by French investigators after ultrasound based studies the “ensemble uretro clitoridovulvaire.”11

Previous studies have used confusing terminology or techniques that have failed clearly to demonstrate clitoral anatomy. Recently MRI of couples copulating have been shown in sagittal section,12 the plane which in these studies least clearly displays the clitoris. In the same study the male subject only was administered sildenafil, relatively enhancing the signal intensity of the penis and further obscuring the clitoris. In another MRI study in which a woman with true hermaphroditism was depicted13 the term corpus spongiosum was used in reference to the bulbs. In this study the clitoris was noted to be barely visible, part of the difficulty again being the choice of plane, ie sagittal rather than axial, the latter being the plane of preference for clitoral anatomy.

CONCLUSIONS

We observed that normal clitoral anatomy in healthy volunteers can be well displayed by MRI using fat saturation techniques without using any contrast agent. The bright erectile tissue of the clitoris surrounds the urethrovaginal complex anterolaterally. The bulbs are recognized as parts of the clitoris and they should be preferably called bulbs of clitoris rather than vestibular bulbs. Axial views are more useful for depicting most of the clitoris, and the sagittal and coronal planes are complementary. This study complements cadaveric studies of clitoral anatomy and provides further insights into the role and scope of MRI for demonstrating normal anatomy.

Professor John Hutson, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne supervised the dissection based female urogenital anatomy project.

APPENDIX

Each MRI study is accompanied by a diagram to highlight the clitoris: the anatomy of its components, neurovascular supply and the related structures, the urethra and vagina.

Footnotes

Study received institutional review board approval.

Supported by the Bruce Pearson Fellowship of the Urological Foundation of Australia and National Institute of Health Grants DK51405 and HD 38665.

References

- 1.Suh DD, Yang CC, Cao Y, Garland PA, Maravilla KR. Magnetic resonance imaging anatomy of the female genitalia in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. J Urol. 2003;170:138. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000071880.15741.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maravilla KR, Cao Y, Heiman JR, Garland PA, Peterson BT, Carter WO, et al. Serial MR imaging with MS-325 for evaluating female sexual arousal response: determination of intrasubject reproducibility. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;18:216. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deliganis AV, Maravilla KR, Heiman JR, Carter WO, Garland PA, Peterson BT, et al. Female genitalia: dynamic MR imaging with use of MS-325: initial experiences evaluating female sexual response. Radiology. 2002;225:791. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2253011160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Connell HE, Hutson JM, Anderson CR, Plenter RJ. Anatomical relationship between urethra and clitoris. J Urol. 1998;159:1892. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore LJ, Clarke AE. Clitoral conventions and transgressions: graphic representations in anatomy texts, c1900–1991. Feminist Studies. 1995;21:255. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheehan E. Victorian clitoridectomy: Isaac Baker Brown and his harmless operative procedure. Med Anthropol Newsl. 1981;12:9. doi: 10.1525/maq.1981.12.4.02a00120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegelman ES, Banner MP, Ramchandani P, Schnall MD. Multicoil MR imaging of symptomatic female urethral and periurethral disease. Radiographics. 1997;17:349. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.17.2.9084077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bannister LH, Dyson M. Reproductive organs of the female. Vagina; female sexual organs. In: Gray’s Anatomy, 38th ed. Edited by P. L. Williams, L. H. Bannister, M. M. Berry, P. Collins, M. Dyson, J. E. Durrek et al. New York: Churchill Livingstone, sect. 14, pp. 1875–1877, 1995

- 9.Snell RS. The perineum. In: Clinical Anatomy for Medical Students, 5th ed. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., chapt. 8, pp. 347–379, 1955

- 10.Baggish MS, Steele AC, Karram MM. The relationship of the vestibular bulb and corpora cavernosa to the female urethra: a microanatomic study. Part 2 J Gynecol Surg. 1999;15:171. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenck LC, Vanneuville G, Monnet JP, Harmand Y. Sphincter urétral (point G). Corrélations anatomocliniques. Rev Fr Gynec Obst. 1992;87:65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schultz WW, van Andel P, Sabelis I, Mooyaart E. Magnetic resonance imaging of male and female genitals during coitus and female sexual arousal. Br Med J. 1999;319:1596. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hricak H, Chang YC, Thurnher S. Vagina: Evaluation with MRI imaging. Part I Normal anatomy and congenital anomalies. Radiology. 1988;169:169. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.1.3420255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]