Abstract

Objective To determine to what extent individuals with various family histories of colorectal cancer (from one to three or more affected first degree relatives) benefit from colonoscopic surveillance.

Design Prospective, observational study of high risk families, followed up over 16 years.

Setting Tertiary referral family cancer clinic in London.

Participants 1678 individuals from families registered with the clinic. Individuals were classified according to the strength of their family history: hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (if they fulfilled the Amsterdam criteria), and one, two, or three affected first degree relatives (moderate risk).

Interventions Colonoscopy was initially offered at five year intervals or three year intervals if an adenoma was detected.

Main outcome measures The incidence of adenomas with high risk pathological features or cancer. This was analysed by age, the extent of the family history, and findings on previous colonoscopies. The cohort was flagged for cancer and death. Incidence of colorectal cancer and mortality during over 15 000 person years of follow-up were compared with those expected in the absence of surveillance.

Results High risk adenomas and cancer were most common in families with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (on initial colonoscopy 5.7% and 0.9%, respectively). In the families with moderate risk, these findings were particularly uncommon under age 45 (1.1% and 0%) and on follow-up colonoscopy if advanced neoplasia was absent initially (1.7% and 0.1%). The incidence of colorectal cancer was substantially lower—80% in families with moderate risk (P = 0.00004), and 43% in families with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (P = 0.06)—than the expected incidence in the absence of surveillance when the family history was taken into account.

Conclusions Colonoscopic surveillance reduces the risk of colorectal cancer in people with a strong family history. This study confirms that members of families with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer require surveillance with short intervals. Individuals with a lesser family history may not require surveillance under age 45, and if advanced neoplasia is absent on initial colonoscopy, surveillance intervals may be lengthened. This would reduce the demand for colonoscopic surveillance.

Introduction

Individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer are at increased risk of developing colorectal cancer.1-6 This risk is greater when associated with early age of onset or multiple affected relatives. High penetrance dominant genes yielding clinical syndromes such as familial adenomatous polyposis and hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) account for 3-5% of colorectal cancers.7 Moderate familial clustering accounts for about a third of colorectal cancer but represents a heterogeneous group attributable to a combination of genes, environment, and chance.

Following well defined guidelines for colonoscopic surveillance has been shown to reduce incidence of and mortality due to colorectal cancer in individuals with a family history of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer. In individuals with less pronounced family histories, surveillance has been recommended from age 40 or 10 years before the age of diagnosis of the youngest relative.8 Evidence regarding the benefit of surveillance in such individuals is insufficient, and it is unclear in whom colonoscopy should be undertaken, from what age, and at what frequency.

In 1986, a family cancer clinic was opened in London to provide counselling and screening to patients at high risk.9 We report the outcome of initial and subsequent colonoscopies and the incidence of colorectal cancer during 16 years of follow-up.

Methods

Families are registered with the St Mark's Hospital Cancer Research UK family cancer clinic. Colonoscopic surveillance is offered to individuals with an empirical risk of death from colorectal cancer of at least one in 10.1,9 Examinations (excluding those in patients with an earlier cancer) between March 1987 and December 2003 are included here. All individuals have been flagged in the NHS central register providing information on cancer registration, death, and emigration.

The patient information advisory group of the Department of Health allowed flagging and tracing without Section 60 support as the patients were already directly under our clinical care. Patients consented to being included on the clinic's database.

When the clinic was started, surveillance was offered from age 25, at five year intervals or three year intervals if an adenoma was diagnosed. Later, individuals in a family with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer were offered colonoscopy every one to three years.10

Consultant physicians at St Mark's Hospital performed 85% of colonoscopies. Other results came from the relevant hospitals. Adenomas with villous histology, a diameter of at least 10 mm, or high grade dysplasia are defined as high risk. All other adenomas are termed simple. Advanced neoplasia is defined as a high risk adenoma or cancer. Family histories were classified into four groups. Group 1 comprises families in which colorectal cancer has been diagnosed in one first degree relative under age 45, with no other cases. Group 2 comprises families with two affected first degree relatives, or one first degree and one second degree relative, who are first degree relatives of each other. Group 3 comprises families with at least three individuals affected over two generations, one a first degree relative of the other two, but no cases diagnosed under age 50. Group 4 consists of families who fulfil the Amsterdam criteria (ACI or ACII)11 and families in whom a mutation for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer has been found regardless of family history. We refer to groups 1-3 collectively as having a moderate risk for familial colorectal cancer. We applied this classification to all first degree relatives of an affected individual, regardless of subsequent cancers in the family.

Statistical methods

We report the most advanced lesion on a given examination. Outcomes of initial colonoscopies are presented as directly standardised proportions. We used multinomial logistic regression to adjust the proportions of different outcomes on follow-up. We standardised and adjusted for age, sex, and family history, as appropriate. P values are from (multinomial) logistic regression, adjusting for confounders and taking account of dependence between related individuals. Rates of advanced neoplasia use the time between the first and last surveillance.

We used sex specific and age specific rates from England for 1997 to calculate expected numbers of cancers.12 We used incidence rates and survival proportions (for colorectal cancer diagnosed in 1997 in England) rather than mortality data to calculate expected numbers of deaths.13

We applied three sets of familial, age specific, relative risks corresponding to our best estimate and what we consider to be the lowest and highest reasonable estimate (see table A on bmj.com) to the population rates.

Results

Initial colonoscopies

Altogether 1678 individuals (1055 women) had colonoscopies during the study period (table 1). The median age at the initial colonoscopy was 41. Individuals from group 4 (fulfilling the Amsterdam criteria) and from group 1 (families with one case diagnosed under age 45, and no other cases) were on average five to eight years younger than from groups 2 and 3. Ninety seven per cent of examinations reached the caecum. The others were either repeated or the patient was given a barium enema.

Table 1.

Characteristics of individuals undergoing surveillance at initial colonoscopy

|

No (%) female (n=1055)

|

Median age in years at first colonoscopy (range)

|

No (%) of individuals in age group

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family risk | No of families | No of individuals | 20-34 | 35-44 | 45-64 | ≥65 | ||

| Group 4 (Amsterdam criteria) | 290 | 554 | 344 (62) | 38 (20-82) | 213 (38.5) | 158 (28.5) | 164 (29.6) | 19 (3.4) |

| Group 3* | 242 | 391 | 257 (66) | 46 (25-79) | 68 (17.4) | 109 (27.9) | 190 (48.6) | 24 (6.1) |

| Group 2† | 379 | 536 | 317 (59) | 42 (20-78) | 145 (27.1) | 171 (31.9) | 201 (37.5) | 19 (3.5) |

| Group 1‡ | 148 | 197 | 137 (70) | 37 (20-68) | 82 (41.6) | 57 (28.9) | 53 (26.9) | 5 (2.5) |

| Total | 1059 | 1678 | 1055 (63) | 41 (20-82) | 508 (30.3) | 495 (29.5) | 608 (36.2) | 67 (4.0) |

Includes families with colorectal cancer in at least three individuals affected over two generations, one a first degree relative of the other two, but no cases diagnosed under age 50.

Includes families with two affected first degree relatives, or one first degree and one second degree relative, who are first degree relatives of each other.

Includes families in which colorectal cancer has been diagnosed in one first degree relative under age 45, with no other cases.

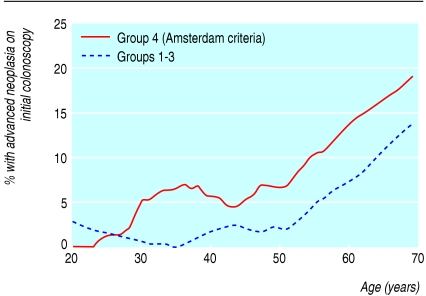

Table 2 presents the results of the initial colonoscopies: three quarters were normal, and 9% found only metaplastic polyps. The likelihood of finding an adenoma or cancer increased with age (P < 0.0001). Advanced neoplasia was seen in 3.8% overall, increasing from 2.0% in people younger than 35 to 14.9% in those aged 65 and older (fig 1). Cancer was found in five individuals (four from group 4—Amsterdam, and one from group 3—three or more affected individuals, but no cases diagnosed under age 50). The adjusted proportion with advanced neoplasia was highest in group 4 and lowest in individuals from group 1 (χ23 = 16.7, P = 0.0008, table 2). Individuals from group 1 were also least likely to have simple adenomas (7.8% compared with 12.8-16.5% in the other groups).

Table 2.

Colonoscopic findings (most neoplastic lesion for each individual) at initial surveillance colonoscopy by family risk group and age. Values are numbers (percentages) of patients

| Risk group by age | Normal finding | Metaplastic polyp | Simple adenoma | Multiple simple adenomas | High risk adenoma | Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 4 (Amsterdam criteria): | ||||||

| 20-34 (n=213) | 176 (83.2) | 13 (5.9) | 14 (6.4) | 2 (0.9) | 6 (2.7) | 2 (0.9) |

| 35-44 (n=158) | 115 (72.8) | 10 (6.3) | 23 (14.5) | 1 (0.6) | 8 (5.1) | 1 (0.6) |

| 45-64 (n=164) | 89 (53.8) | 26 (16.0) | 31 (19.1) | 5 (3.1) | 12 (7.4) | 1 (0.6) |

| ≥65 (n=19) | 11 (55.8) | 1 (5.5) | 3 (16.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (17.0) | 1 (5.1) |

| Overall*

|

391 (68.7)

|

50 (9.3)

|

79 (15.4)

|

34 (6.6)

|

||

| Group 3†: | ||||||

| 20-34 (n=68) | 65 (95.4) | 1 (1.5) | 2 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 35-44 (n=109) | 83 (76.5) | 10 (9.0) | 15 (13.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| 45-64 (n=190) | 112 (57.9) | 15 (8.1) | 48 (25.9) | 6 (3.2) | 9 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| ≥65 (n=24) | 13 (54.2) | 4 (16.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.3) | 4 (16.6) | 1 (4.2) |

| Overall*

|

273 (72.9)

|

30 (7.2)

|

73 (16.5)

|

15 (3.3)

|

||

| Group 2†: | ||||||

| 20-34 (n=145) | 118 (82.4) | 14 (9.1) | 11 (7.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| 35-44 (n=171) | 136 (79.6) | 11 (6.4) | 20 (11.7) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| 45-64 (n=201) | 144 (72.1) | 18 (8.8) | 26 (12.7) | 5 (2.5) | 8 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| ≥65 (n=19) | 6 (33.3) | 4 (20.5) | 7 (35.9) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Overall*

|

404 (76.2)

|

47 (8.5)

|

71 (12.8)

|

14 (2.5)

|

||

| Group 1†: | ||||||

| 20-34 (n=82) | 72 (86.3) | 8 (11.0) | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 35-44 (n=57) | 51 (90.0) | 3 (5.0) | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| 45-64 (n=53) | 40 (74.4) | 5 (9.9) | 8 (15.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ≥65 (n=5) | 3 (57.1) | 1 (22.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Overall* | 166 (81.8) | 17 (9.8) | 13 (7.8) | 1 (0.6) | ||

Group 2 includes families with two affected first degree relatives, or one first degree and one second degree relative, who are first degree relatives of each other. Group 1 includes families in which colorectal cancer has been diagnosed in one first degree relative under age 45, with no other cases.

Percentages may not correspond with the absolute numbers because of standardisation.

Standardised by age.

Group 3 includes families with colorectal cancer in at least three individuals affected over two generations, one a first degree relative of the other two, but no cases diagnosed under age 50.

Fig 1.

Advanced neoplasia and age at initial colonoscopy. The proportion at each age was calculated by using a locally linear smoother.14 This is a more sophisticated version of a running mean

Follow-up colonoscopies

During the study, 1143 individuals (from 740 families) had at least two colonoscopies: 652 had three or more. Altogether 8865 person years elapsed between the initial and the final colonoscopy (3020 in group 4 and 5845 in groups 1-3). The sex and age distribution at first colonoscopy in individuals who had two or more colonoscopies was similar to that in all 1678 individuals, but individuals with strong family histories were more likely to have been rescreened. The median number of years between successive colonoscopies was 3.3 in group 4, 4.6 in group 3, 5.1 in group 2, and 5.1 in group 1.

Incidence of neoplasia on follow-up colonoscopy

When adjusted for age and sex, adenomas were seen on follow-up (colonoscopies after the initial examination) in 26% of group 4, 25% of group 3, 21% of group 2, and 13% of group 1. The adjusted proportions of high risk adenomas and cancer were both greatest in group 4—Amsterdam criteria (5.0% and 1.0%, respectively) compared with 1.7% and 0.1% in groups 1-3—moderate risk (P = 0.005 and P = 0.048, respectively). Advanced neoplasia below the age of 50 on follow-up was most common in group 4 (4.6%). It was 0.5% in individuals from group 3, 0.4% in those from group 2, and 2.2% in those from group 1 (compared with group 4; P = 0.03, P = 0.014, P = 0.32, respectively).

Follow-up findings in individuals at moderate risk were related to initial findings (table 3). Advanced neoplasia on follow-up was most common (12%) in individuals with advanced neoplasia on initial colonoscopy. Seven of the 12 individuals with multiple adenomas on initial colonoscopy had an additional adenoma on follow-up, but none had advanced neoplasia. The incidence of advanced neoplasia during follow-up in people without advanced neoplasia initially depends on family history (P = 0.002) and increases (P = 0.044) with age (table 4). Incidence of advanced neoplasia in people with advanced neoplasia initially was high: 56 per 1000 years in individuals with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer and 28 per 1000 years in individuals with moderate risk (table 4).

Table 3.

Most advanced neoplastic lesion on follow-up surveillance colonoscopy in individuals at moderate familial risk (groups 1-3). Values are numbers (percentages) of patients

|

Most advanced lesion on follow-up colonoscopy

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most advanced lesion on initial colonoscopy | Normal | Metaplastic polyp | Simple adenoma | Multiple simple adenomas | High risk adenoma | Colorectal cancer |

| Normal (n=545) | 406 (73) | 53 (10) | 78 (15) | 3 (1) | 5 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Metaplastic polyp (n=67) | 34 (52) | 17 (25) | 13 (19) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Simple adenoma (n=112) | 51 (49) | 16 (14) | 35 (30) | 6 (5) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Multiple simple adenomas (n=12) | 3 (29) | 2 (18) | 5 (41) | 2 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| High risk adenoma (n=23) | 4 (26) | 4 (21) | 8 (34) | 3 (7) | 4 (12) | 0 (0) |

Percentages are of the number with each initial finding and are adjusted for age and sex.

Table 4.

Rates of advanced neoplasia (absolute number/person years of follow up) on follow-up surveillance colonoscopy, per 1000 person years

| Age at next colonoscopy | Moderate risk (groups 1-3) | Amsterdam citeria (group 4) |

|---|---|---|

|

No advanced neoplasia on first colonoscopy

|

|

|

| 20-34 | 0.0 (0/462) | 3.6 (2/561) |

| 35-44 | 1.2 (2/1646) | 5.0 (4/803) |

| 45-64 | 2.3 (7/3045) | 6.7 (9/1351) |

| 65+ | 4.0 (2/500) | 19.7 (2/101) |

|

Advanced neoplasia on first colonoscopy

|

|

|

| All ages | 27.6 (4/144.8) | 56.5 (7/124.0) |

Cancer incidence and mortality

In addition to six cancers detected at initial colonoscopy, 11 subsequent cancers occurred (eight were detected on surveillance), eight of these in individuals with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer. In three cases, the colonoscopic interval was over five years. Six individuals died within 36 months of diagnosis; the other five patients were alive on 31 December 2002 (3.5-15 years after diagnosis).

Analysis of all cause mortality shows that death certification is complete up to December 2002. By that time, five patients had died from colorectal cancer during 13 347 years of follow-up. The death rate due to colorectal cancer in individuals at moderate risk is close to what one would have expected in the general population, but for group 4 (Amsterdam citeria) the observed mortality is nearly five times greater than in the general population. Despite these discouraging observations, our best estimates of the underlying risk in our cohort yields significant reduction in mortality: 81% in moderate-risk and 72% in group 4 (table 5).

Table 5.

Observed number of cases of and deaths from colorectal cancer with expected numbers using the best estimate (plausible range) of risk based on family history

|

Best estimate

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | Standardised risk ratio† | Plausible range of standardised risk ratio‡ | |

|

Deaths from colorectal cancer

|

(followed to 31 December 2002)

|

|

||

| Moderate risk | 2 | 10.7 | 0.19** | 0.10***-0.38 |

| Group 4§ | 3 | 10.9 | 0.28* | 0.20***-0.59 |

|

Cases of colorectal cancer

|

|

|

|

|

| Between first and last colonoscopy (excluding those detected on first colonoscopy)

| ||||

| Moderate risk | 1 | 13.4 | 0.08*** | 0.04***-0.15* |

| Group 4§ | 8 | 16.5 | 0.49* | 0.35***-1.04 |

| In individuals followed for at least 3 years (to 31 December 2001)

|

|

|||

| Moderate risk | 4 | 19.9 | 0.20*** | 0.11***-0.41 |

| Group 4§ | 11 | 19.2 | 0.57 | 0.41***-1.23 |

| In individuals followed for at least 3 years (to 31 December 2003)

|

|

|||

| Moderate risk | 4 | 26.5 | 0.15*** | 0.08***-0.30** |

| Group 4§ | 11 | 26.6 | 0.41** | 0.30***-0.89 |

*One sided P<0.025. **One sided P<0.005. ***One sided P<0.0005.

Standardised risk ratio: O/E=observed/expected.

O/E based on the expected number of cases when the highest and the lowest reasonable values for the familial risk are used.

Families meeting the Amsterdam criteria.

Analysis of the incidence of all cancers (excluding colorectal and endometrial cancer) shows that follow-up was complete up to December 2001. Fifty five cancers were found compared with 48.2 expected, with no decrease in the rate for 2001 compared with 2000.

Excluding cancers detected on the initial colonoscopy (prevalent cancers), eight colorectal cancers were diagnosed during active surveillance in individuals from group 4. That is nine times greater than expected from a “normal” population. By contrast, the one cancer in the group at moderate risk compares to 2.3 expected in a “normal” population. However, the eight cancers in group 4 are still fewer than half the number expected when we use our best estimate of the cancer rates in unscreened relatives of individuals with suspected hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (P = 0.03, table 5).

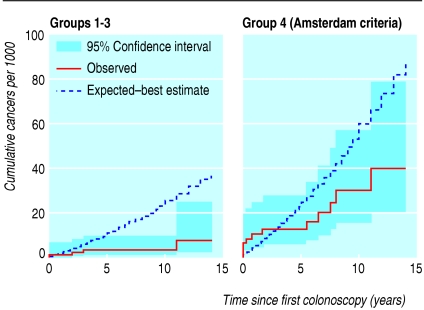

Figure 2 shows the cumulative incidence curve as a function of time since first colonoscopy together with the expected curve based on the best estimates. The prevalent cancers detected during screening cause a jump in the observed cumulative incidence at time zero. It is 0.5 years before the curves cross for the moderate risk group and three years for group 4.

Fig 2.

Observed cumulative incidence curve as a function of time (in years) since first colonoscopy together with the expected curve based on the best estimates

Analysis including all cancers diagnosed up to 31 December 2003 in individuals first screened before 31 December 2000 yields similar results to the analysis excluding prevalent cancers. Both analyses show a reduction in the incidence of cancer compared with our best estimate of the underlying risk. However, particularly in individuals at moderate risk, the inclusion of prevalent cancers reduces the magnitude of the benefit of colonoscopic surveillance on the incidence of cancer.

Discussion

Colonoscopic surveillance is effective in preventing colorectal cancer in individuals from families with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (group 4) and in individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer that does not meet the Amsterdam criteria. However, colonoscopic surveillance in the families at moderate risk seems not indicated until age 45 (or even 50), and this is true even for the relatives of young patients. Furthermore, surveillance intervals of more than five years may be appropriate in individuals with a moderate risk family history (groups 1-3) in whom no advanced pathology is found. This study also confirms the need for frequent colonoscopic surveillance from a young age in families with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer.

Limitations of the study

A potential limitation of the study is that there may be further unreported cases of cancer. This has been minimised by intense efforts to trace all individuals via their general practitioner and all individuals enrolled in the clinic have been flagged on the NHS central register, so that information on emigration, cancer, and death (including cause of death) are available. Analysis of non-colorectal cancers shows that little or no under-reporting occurred. The main weakness is the lack of a robust control group (but randomising individuals to no surveillance would be unethical). Instead we estimated expected outcomes by using concurrent population rates and published estimates of relative risk with respect to family history.

Strengths of the study

Prospective data on the outcome of colonoscopy in individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer, particularly from families at moderate risk, are sparse. One of the main strengths of this paper is that the study group is large and has been followed up for 15 years (resulting in over 11 000 person years of follow-up) and includes a substantial number of individuals from families at moderate risk

In some previous studies, individuals with colorectal cancer on initial colonoscopy were excluded from analysis.6,15 This biases results in favour of colonoscopy. The analyses here take into account prevalent cases, avoiding this bias.

Evidence exists that colorectal cancer in people with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer can be reduced substantially with colonoscopic surveillance,8 but, although colonoscopic surveillance has been recommended for individuals with moderate familial risk, no previous prospective studies have been undertaken. In individuals with a moderate risk family history, very little advanced neoplasia occurred below the age of 45, and these findings are in line with recent studies.5-17

Role of colonoscopic polypectomy

Colonoscopic polypectomy has been shown to decrease the incidence of colorectal cancer in a large cohort study6 as well as in clinical practice18 and to decrease both the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer in individuals with a family history of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer. It is also considered by some to be a safe tool for population screening.19 Clear guidelines exist for colorectal surveillance in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer families,20 but guidelines and practices for individuals at moderate risk on the basis of their family history are heterogeneous.21-25

Concerns exist about colonoscopic surveillance in individuals with a moderate risk family history, as some will not be at increased risk. Dunlop et al calculated that if surveillance were offered to individuals aged 30-70 who have two direct relatives affected or one under age 45 then 235 000 individuals would be eligible in the United Kingdom.25 Even if the age of initiating surveillance is raised, the potential burden on resources is immense. Colonoscopy is associated with a small risk of serious complications, and this may substantially outweigh any benefits in people at low risk.

Importance of findings

In this study, only one incident cancer was detected on surveillance in an individual with a moderate risk family history during 9281 person years of follow-up. In families at moderate risk, advanced neoplasia is very rare below the age of 45 and, if not seen initially, it remains uncommon (under age 65) if follow-up colonoscopy is carried out within six years. These findings are important because individuals with a moderate risk family history who are under age 65 with no advanced neoplasia can be considered to be at low risk and extended surveillance intervals may be sufficient. Individuals with a moderate risk family history in whom advanced neoplasia is seen on initial colonoscopy should continue with colonoscopy every three years. The low yield of advanced neoplasia under the age of 45 is true also of those with a first degree relative affected under age 45. Only 4% of 139 individuals in group 1—families with one case of colorectal cancer diagnosed under age 45, and no other cases—screened under age 45 (mean age 33) had an adenoma of any description. Despite the increased risk of colorectal cancer in this group1-3 individuals' absolute risk therefore remains small and the benefit of screening seems minimal below the age of 45.

The greatest benefit of surveillance colonoscopy is in families with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, although even with surveillance incidence of colorectal cancer is greater in this group than in the general population. Advanced neoplasia was seen in all age groups in these families, which supports the recommendation of colonoscopic surveillance from the age of 20-25. The high incidence of colorectal cancers within three years of a colonoscopy is further evidence that progression from adenoma to carcinoma may be accelerated in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer.26,27

What is already known on this topic

Individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer are themselves at increased risk, and colonoscopic surveillance is recommended

Well defined guidelines exist for colonoscopic surveillance in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer

Prospective studies have shown that surveillance reduces the incidence of and mortality due to colorectal cancer

Evidence regarding the benefit of surveillance in individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer who do not meet the Amsterdam criteria for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer is insufficient

It is unclear in whom colonoscopy should be undertaken, from what age, and at what frequency

What this study adds

Colonoscopic surveillance is effective in preventing colorectal cancer in individuals with a history of colorectal cancer in a first degree relative even if this does not meet the Amsterdam criteria for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer syndrome

Surveillance in these families does not seem to be indicated until the age of 45 (or even 50), and in the absence of substantial pathology intervals of more than five years may be appropriate

Supplementary Material

Statistical methods and a supplemental table are on bmj.com

Statistical methods and a supplemental table are on bmj.com

We thank Helen Crowne, Steve Edmeades, and Linda Godfrey from Cancer Research UK clinical information systems for setting up the Bobby Moore database and John Northover and Joan Slack, who established the family cancer clinic. We also thank Christopher Williams and other members of the Wolfson endoscopy unit at St Mark's Hospital for their contributions to the colonoscopic surveillance; Maggie Stevens and Julie Stokes for their administrative input; and nurses Carole Cummings and Sheila Goff for their help with the patients. We thank the Office for National Statistics for accessing the information from the NHS central register. Finally we thank all the individuals and families who have taken part in this study.

Contributors: IDE wrote the first draft of the paper. PS supervised the analysis of the data. JA analysed the data and coordinated the writing of the paper. HJWT is responsible for the clinical management of the patients at the family cancer group and initiated the analysis of the follow-up colonoscopies. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper. HJWT is the guarantor. He accepts full responsibility for the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: North Thames Regional Health Authority Responsive Funding R&D Committee provided the salary of a research fellow (IDE).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Harrow Research Ethics Committee, for “flagging on NHS Central Register of family cancer clinic patients undergoing colonoscopic surveillance.”

References

- 1.Lovett E. Family studies in cancer of the colon and rectum. Br J Surg 1976;63: 13-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Speizer FE, Willett WC. Prospective study of family history and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 1994;331: 1669-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.St John DJ, McDermott FT, Hopper JL, Debney EA, Johnson WR, Hughes ESR. Cancer risk in relatives of patients with common colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med 1993;118: 785-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarvinen HJ, Aarnio M, Mustonen H, Aktan-Collan K, Aaltonen LA, Peltomaki P, et al. Controlled 15-year trial on screening for colorectal cancer in families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2000;118: 829-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradshaw N, Holloway S, Penman I, Dunlop MG, Porteous ME. Colonoscopy surveillance of individuals at risk of familial colorectal cancer. Gut 2003;52: 1748-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy: The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med 1993;334: 82-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lynch HT, de la Chapelle A. Genetic susceptibility to non-polyposis colorectal cancer. J Med Genet 1999;36: 801-18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burt RW. Colon cancer screening. Gastroenterology 2000;119: 837-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houlston RS, Murday V, Harocopos C, Williams CB, Slack J. Screening and genetic counselling for relatives of patients with colorectal cancer in a family cancer clinic. BMJ 1990;301: 366-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber T. Clinical surveillance recommendations adopted for HNPCC. Lancet 1996;348: 465. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasen HFA, Watson P, Mecklin J-P, Lynch HT. New clinical criteria for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, Lynch syndrome) proposed by the International Collaborative Group on HNPCC. Gastroenterology 1999;116: 1453-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Statistics. Cancer statistics—registrations 1995-1997. Series MN1 no 28. London: Stationery Office, 2001.

- 13.Sasieni P. The expected number of deaths from cancer during follow-up of an initially cancer-free cohort. Epidemiology 2003;14: 108-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sasieni P. Symmetric nearest neighbour linear smoothers. Stata Tech Bull 1995;24: 10-4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atkin WS, Morson DM, Cuzick J. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer after excision of rectosigmoid adenomas. N Engl J Med 1992;326: 658-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dowling DJ, St John DJ, Macrae FA, Hopper JL. Yield from colonoscopic screening in people with a strong family history of common colorectal cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000;15: 939-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindgren G, Liljegren A, Jaramillo E, Rubio C, Lindblom A. Adenoma prevalence and cancer risk in familial non-polyposis colorectal cancer. Gut 2002;50: 228-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Citarda F, Tomaselli G, Capocaccia R. Efficacy in standard clinical practice of colonoscopic polypectomy in reducing colorectal cancer incidence. Gut 2001;48: 812-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imperiale TF, Wagner DR, Lin CY, Larkin GN, Rogge JD, Ransohoff DF. Results of screening colonoscopy among persons 40 to 49 years of age. N Engl J Med 2002;346: 1781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burke W, Petersen G, Lynch P, Botkin J, Daly M, Garber J, et al. Consensus statement. Recommendations for follow-up care of individuals with an inherited predisposition to cancer. I. Hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. JAMA 1997;277: 915-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byers T, Levin B, Rothernberger D, Dodd GD, Smith RA. American Cancer Society guidelines for screening and surveillance for early detection of colorectal polyps and cancer: update 1997. CA Cancer J Clin 1997;47: 154-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodgson SV, Bishop DT, Dunlop MG, Evans DRG, Northover JMA. Suggested screening guidelines for familial colorectal cancer. J Med Screen 1995;2: 45-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ivanovich JL, Thomas MS, Read E, Ciske DJ, Kodner IJ, Whelan AJ. A practical approach to familial and hereditary colorectal cancer. Am J Med 1999;107: 68-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology 1997;112: 594-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunlop MG. Screening for people with a family history of colorectal cancer. BMJ 1997;314: 1779-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lynch HT, Smyrk T, Jass JR. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and colonic adenomas: Aggressive adenomas? Semin Surg Oncol 1995;11: 406-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rijcken FEM, Hollema H, Kleibucker JH. Proximal adenomas in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer are prone to rapid malignant transformation. Gut 2002;50: 382-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.