Abstract

Using tumor necrosis factor receptor type 2 (TNFR2)-deficient mice and generating bone marrow chimeras which express TNFR2 on either hematopoietic or nonhematopoietic cells, we demonstrated the requirement for TNFR2 expression on tissue cells to induce lethal cerebral malaria. Thus, TNFR2 on the brain vasculature mediates tumor necrosis factor-induced neurovascular lesions in experimental cerebral malaria.

Congested microvessels with sequestered parasitized erythrocytes and leukocytes are typical pathological findings in brain sections from patients with cerebral malaria (CM). Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) has been found to be a crucial mediator for the neurovascular lesions in both human (10, 13) and experimental CM (6). Activation of the brain's vascular endothelium has been demonstrated by the enhanced expression of intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) (8, 19) and TNF receptor type 2 (TNFR2) (14). The critical involvement of TNFR2 in the development of experimental CM has been clearly demonstrated by the use of TNFR2-deficient mice (4), which were protected from the lethal syndrome of CM and did not show enhanced ICAM-1 expression on brain microvascular endothelial cells (14). The role of TNFR2 in TNF-associated pathology is not fully understood but implicates activation of NF-κB, which is important for triggering the proinflammmatory cytokine cascades (1). NF-κB activation is crucially involved in autoimmune disease (3, 12, 16) and the mortality of sepsis (2). TNFR2 has been shown to be preferentially activated by membrane-bound TNF (11), and cell-associated TNF has been shown to be an essential mediator in CM (14). In addition to the infected erythrocytes and leukocytes sequestering in the microvasculature of the brain, platelet aggregates seem to contribute to the neurovascular lesions by plugging the microvessels (8; C. D. Mackenzie, R. A. Carr, A. K. Das, S. B. Lucas, N. G. Liomba, G. E. Grau, M. E. Molyneux, and T. E. Taylor, Abstr. 48th Annu. Meet. Am. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg., abstr. 780, p. 475, 1999). A number of platelet membrane molecules can possibly participate in the enhanced adhesion of platelets onto activated endothelium and white blood cells (reviewed in reference 15).

Since the previous work suggested that the interaction of TNF-producing blood cells with microvascular endothelial cells leads to the pathological lesions of CM, we were interested in identifying the cells which express the TNFR2 responsible for the development of the lethal CM syndrome induced in mice by intraperitoneal injection of 106 erythrocytes parasitized by Plasmodium berghei ANKA (7).

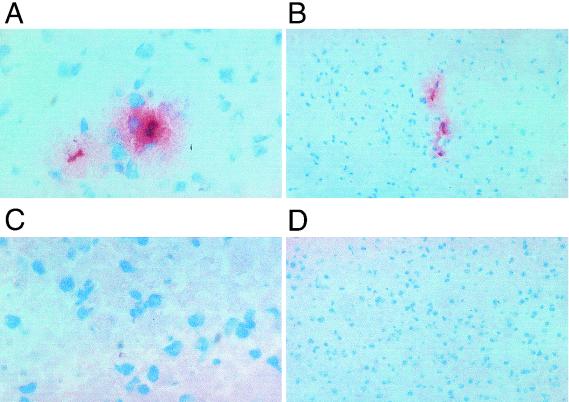

Earlier experiments have shown that the presence of TNFR2 is crucial for the development of experimental CM and that neutralization of leukocyte function-associated antigen-1, one of the ligands for ICAM-1, blocks platelet sequestration and prevents the damage of the brain microvasculature (9). Staining of frozen brain sections from mice with a monoclonal antibody specific for platelets (17) demonstrated that, similar to what has been seen in human pathological sections, platelet aggregation, sequestration, and extravasation, together with the presence of trapped leukocytes, were found to be associated with the brain microvessels of those mice which died with neurological symptoms (Fig. 1A and B). In contrast, no such platelet staining was seen in CM-resistant mice deficient for TNFR2 (4) (Fig. 1C and D). In fact, this platelet staining pattern is very supportive of the idea that plugging of the fine vessels by platelets might also contribute to the observed damage of the brain microvasculature, as was suggested previously (9).

FIG. 1.

Staining of sequestered platelets in brain microvessels during CM. (A and B) Platelet staining on brain sections from a malaria-infected mouse with cerebral symptoms at day 10 postinfection. (C and D) Platelet staining on brain sections from an infected Tnfr20 mouse with no cerebral symptoms at day 10 postinfection. Magnifications, ×400 (A and C) and ×650 (B and D).

To evaluate the cell compartment of the host responsible for mediating the TNF-dependent mortality associated with CM, we generated chimeric mice by adoptive bone marrow transplantation (107 bone marrow cells were injected intravenously after lethal X-irradiation with 10 Gy). Either Tnfr20 mice (backcrossed six times to C57BL/6 mice) received wild-type (wt) bone marrow cells or wt mice received bone marrow cells from Tnfr20 donors, thus generating chimeric mice in which the phenotype of the hematopoietic cells differs from that of the rest of the mouse cells with respect to TNFR2 expression. To test for successful adoptive bone marrow cell transfer, the genotype of blood leukocytes in chimeric mice was determined 4 weeks after reconstitution by PCR. In all chimeric mice, specific bands of the donor genotype were detectable (data not shown). Previous experiments using the same bone marrow reconstitution protocol have shown that even though the hematopoietic cells were of mixed genotype after bone marrow reconstitution, such bone marrow transfer changed the phenotype in an immune reaction which was dependent on hematopoietic cells (18). Adoptive bone marrow transplantation restored the susceptibility of Tnfr10 mice to TNF-induced sequestration of leukocytes, whereas a host tissue cell-dependent event, TNF-induced tumor necrosis, was not restored, demonstrating the suitability of the method.

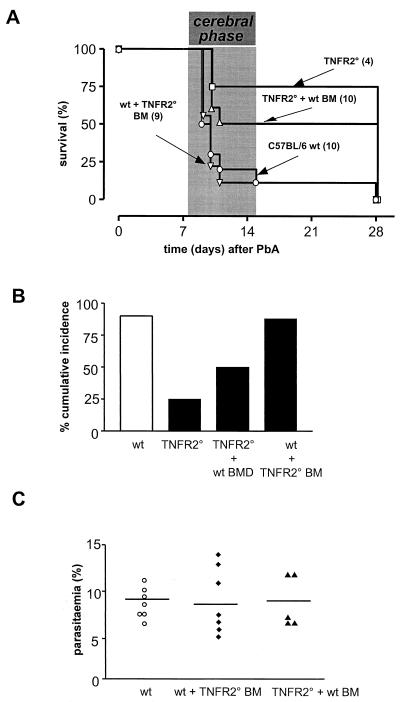

The susceptibilities to CM upon P. berghei ANKA infection were analyzed in chimeric mice of the wt background reconstituted with Tnfr20 bone marrow (n = 9) and in chimeric mice of the Tnfr20 background reconstituted with wt bone marrow (n = 10) and compared to those of wt mice (n = 10) and Tnfr20 mice (n = 4). The results of a survival study showed that the majority of the infected wt mice reconstituted with Tnfr20 bone marrow (8 out of 9) died as rapidly as the majority of the wt mice (9 out of 10), i.e., between days 7 and 15 postinfection (Fig. 2A). In contrast, half of the Tnfr20 mice reconstituted with wt bone marrow (5 out of 10) were protected and died after more than 3 weeks of infection, with severe anemia but no cerebral syndrome. As in the earlier study, the cumulative incidence of CM was significantly reduced in the Tnfr20 mice (P > 0.03, log rank statistic) and was not restored by transfer of wt bone marrow cells (P > 0.02, log rank statistic) (Fig. 2B). This demonstrates that the presence of TNFR2 on blood leukocytes is not sufficient to make mice susceptible to CM. Obviously, host tissue cells, i.e., those in the vasculature, need to be able to express TNFR2 for the brain pathology and the neurological syndrome to occur.

FIG. 2.

Susceptibility of chimeric mice to CM. (A) Survival of C57BL/6 mice (wt, n = 10), Tnfr20 mice (n = 4), wt mice reconstituted with Tnfr20 bone marrow cells (n = 9), and Tnfr20 mice reconstituted with wt bone marrow cells (n = 10) after P. berghei ANKA infection; (B) cumulative incidence of CM occurring between days 7 and 15; (C) degree of malarial infection in chimeric mice compared to that in C57BL/6 wt mice.

Comparison of the numbers of parasitized red blood cells of the individual mice from the different experimental groups revealed identical degrees of malarial infection (Fig. 2C). The levels of parasitemia on day 10 postinfection were not different among the chimeric and the wt mice. This demonstrates that the manipulation associated with the adoptive bone marrow transfer did not change the course of infection. Previous experiments have shown that TNF titers in serum reach the same levels in wt and TNFR1- and TNFR2-deficient mice during the course of infection with P. berghei ANKA (14).

These data support the hypothesis which has evolved from earlier studies that the interaction of membrane TNF on activated mononuclear leukocytes trapped in microvessels of the brain with TNFR2 on endothelial cells is the crucial event in CM (14). In Tnfr20 mice, contrary to what was seen in wt and Tnfr10 mice, a striking absence of sequestered leukocytes and a lack of ICAM-1 upregulation were observed in brain microvessels, events which correlate well with the susceptibility of those mice to CM (5, 8). In addition, we noted an absence of aggregated and sequestered platelets in the brain microvasculatures of mice lacking TNFR2 and found that TNFR2 on endothelial cells seems to be required for initiating the brain pathology of CM, indicating that the mouse model of CM might be suitable for further studies of the molecular events leading to the neurological symptoms.

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Baeuerle, P. A., and D. Baltimore. 1996. NF-κB: ten years after. Cell 87:13-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohrer, H., F. Qiu, T. Zimmermann, Y. Zhang, T. Jllmer, D. Männel, B. W. Bottiger, D. M. Stern, R. Waldherr, H. D. Saeger, R. Ziegler, A. Bierhaus, E. Martin, and P. P. Nawroth. 1997. Role of NFκB in the mortality of sepsis. J. Clin. Investig. 100:972-985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bondeson, J., B. Foxwell, F. Brennan, and M. Feldmann. 1999. Defining therapeutic targets by using adenovirus: blocking NF-kappaB inhibits both inflammatory and destructive mechanisms in rheumatoid synovium but spares anti-inflammatory mediators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:5668-5673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erickson, S. L., F. J. de Sauvage, K. Kikly, K. Carver-Moore, S. Pitts-Meek, N. Gillett, K. C. Sheehan, R. D. Schreiber, D. V. Goeddel, and M. W. Moore. 1994. Decreased sensitivity to tumour-necrosis factor but normal T-cell development in TNF receptor-2-deficient mice. Nature 372:560-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falanga, P. B., and E. C. Butcher. 1991. Late treatment with anti-LFA-1 (CD11a) antibody prevents cerebral malaria in a mouse model. Eur. J. Immunol. 21:2259-2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grau, G. E., L. F. Fajardo, P. F. Piguet, B. Allet, P. H. Lambert, and P. Vassalli. 1987. Tumor necrosis factor (cachectin) as an essential mediator in murine cerebral malaria. Science 237:1210-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grau, G. E., P. F. Piguet, H. D. Engers, J. A. Louis, P. Vassalli, and P. H. Lambert. 1986. L3T4+ T lymphocytes play a major role in the pathogenesis of murine cerebral malaria. J. Immunol. 137:2348-2354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grau, G. E., P. Pointaire, P. F. Piguet, C. Vesin, H. Rosen, I. Stamenkovic, F. Takei, and P. Vassalli. 1991. Late administration of monoclonal antibody to leukocyte function-antigen 1 abrogates incipient murine cerebral malaria. Eur. J. Immunol. 21:2265-2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grau, G. E., F. Tacchini-Cottier, C. Vesin, G. Milon, J. N. Lou, P. F. Piguet, and P. Juillard. 1993. TNF-induced microvascular pathology: active role for platelets and importance of the LFA-1/ICAM-1 interaction. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 4:415-419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grau, G. E., T. E. Taylor, M. E. Molyneux, J. J. Wirima, P. Vassalli, M. Hommel, and P. H. Lambert. 1989. Tumor necrosis factor and disease severity in children with falciparum malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 320:1586-1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grell, M., E. Douni, H. Wajant, M. Lohden, M. Clauss, B. Maxeiner, S. Georgopoulos, W. Lesslauer, G. Kollias, and K. Pfizenmaier. 1995. The transmembrane form of tumor necrosis factor is the prime activating ligand of the 80 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell 83:793-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilliard, B., E. B. Samoilova, T. S. Liu, A. Rostami, and Y. Chen. 1999. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in NF-κB-deficient mice: roles of NF-κB in the activation and differentiation of autoreactive T cells. J. Immunol. 163:2937-2943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwiatkowski, D., A. V. Hill, I. Sambou, P. Twumasi, J. Castracane, K. R. Manogue, A. Cerami, D. R. Brewster, and B. M. Greenwood. 1990. TNF concentration in fatal cerebral, non-fatal cerebral, and uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Lancet 336:1201-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucas, R., P. Juillard, E. Decoster, M. Redard, D. Burger, Y. Donati, C. Giroud, C. Monso-Hinard, T. De Kesel, W. A. Buurman, M. W. Moore, J. M. Dayer, W. Fiers, H. Bluethmann, and G. E. Grau. 1997. Crucial role of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 2 and membrane-bound TNF in experimental cerebral malaria. Eur. J. Immunol. 27:1719-1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Männel, D. N., and G. E. Grau. 1997. Role of platelet adhesion in homeostasis and immunopathology. Mol. Pathol. 50:175-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neurath, M. F., C. Becker, and K. Barbulescu. 1998. Role of NF-κB in immune and inflammatory responses in the gut. Gut 43:856-860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nieswandt, B., B. Echtenacher, F. P. Wachs, J. Schröder, J. E. Gessner, R. E. Schmidt, G. E. Grau, and D. N. Männel. 1999. Acute systemic reaction and lung alterations induced by an antiplatelet integrin gpIIb/IIIa antibody in mice. Blood 94:684-693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoelcker, B., B. Ruhland, T. Hehlgans, H. Bluethmann, T. Luther, and D. N. Männel. 2000. Tumor necrosis factor induces tumor necrosis via tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1-expressing endothelial cells of the tumor vasculature. Am. J. Pathol. 156:1171-1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willimann, K., H. Matile, N. A. Weiss, and B. A. Imhof. 1995. In vivo sequestration of Plasmodium falciparum-infected human erythrocytes: a severe combined immunodeficiency mouse model for cerebral malaria. J. Exp. Med. 182:643-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]