Abstract

Objective To determine the costs and benefits of interventions for maternal and newborn health to assess the appropriateness of current strategies and guide future plans to attain the millennium development goals.

Design Cost effectiveness analysis.

Setting Two regions classified by the World Health Organization according to their epidemiological grouping: Afr-E, those countries in sub-Saharan Africa with very high adult and high child mortality, and Sear-D, comprising countries in South East Asia with high adult and high child mortality.

Data sources Effectiveness data from several sources, including trials, observational studies, and expert opinion. For resource inputs, quantities came from WHO guidelines, literature, and expert opinion, and prices from the WHO choosing interventions that are cost effective database.

Main outcome measures Cost per disability adjusted life year (DALY) averted in year 2000 international dollars.

Results The most cost effective mix of interventions was similar in Afr-E and Sear-D. These were the community based newborn care package, followed by antenatal care (tetanus toxoid, screening for pre-eclampsia, screening and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria and syphilis); skilled attendance at birth, offering first level maternal and neonatal care around childbirth; and emergency obstetric and neonatal care around and after birth. Screening and treatment of maternal syphilis, community based management of neonatal pneumonia, and steroids given during the antenatal period were relatively less cost effective in Sear-D. Scaling up all of the included interventions to 95% coverage would halve neonatal and maternal deaths.

Conclusion Preventive interventions at the community level for newborn babies and at the primary care level for mothers and newborn babies are extremely cost effective, but the millennium development goals for maternal and child health will not be achieved without universal access to clinical services as well.

Introduction

Each year more than 500 000 women die during pregnancy or childbirth1 and more than 4 million babies die in the first 28 days of life, accounting for 38% of mortality in children aged less than 5 worldwide.2 The contrast between countries is stark. Of every 1000 children born in Africa and South East Asia, 44 and 38 die in the neonatal period, respectively, compared with four in high income countries. A similar gulf exists for maternal mortality, with rates in sub-Saharan Africa more than 2.5 times those in Asia, which are in turn more than 20 times those in developed countries.1 Effective interventions to reduce maternal and neonatal deaths exist,3 but they are not available to people living in the poorest parts of the world.4

The member countries of the United Nations agreed to reduce child mortality by two thirds and maternal mortality by three quarters by 2015 as part of the millennium development goals (goals 4 and 5, respectively). To aid decisions on how to more effectively reach these goals that have thus far shown poor progress, information on the costs and impact on health of current and possible new interventions is critical to show what improvements in health could be achieved with different options for expenditure.5 Cost effectiveness analyses of maternal and newborn interventions have, however, usually been restricted to the analysis of individual interventions,6-8 with considerable variation in the analytical methods used. This, combined with variability in the settings in which the analyses were undertaken, limits the value of the existing literature.

Recently, as part of a series on neonatal survival, the cost effectiveness of antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal interventions of proved benefit for reducing neonatal mortality was estimated.3 The series used standardised methods and a form of analysis that allows existing interventions to be evaluated at the same time as possible new interventions.3 We develop this work further by including a more comprehensive list of maternal interventions provided during pregnancy, childbirth, and the neonatal period.

We examined the costs and impact on health of interventions that target the health related millennium development goals. This paper provides policy makers with the necessary information to enable them to evaluate if they are using the resources currently available for maternal and neonatal conditions effectively and efficiently, and how they can best achieve millennium development goals 4 and 5 as new resources become available. A summary paper considers the overall implications of the results presented in this series.9

Methods

The paper by Evans et al provides details on the standardised methods of the WHO choosing interventions that are cost effective (CHOICE) project that were used in this analysis.10 Here we provide additional detail on methods exclusive to this paper.

Interventions

The analysis included 21 interventions and all possible combinations of interventions, taking into account interactions in costs or effectiveness when interventions are implemented together. Table 1 lists the interventions, categorised according to the level of care required to deliver them (first level maternal and newborn care, referral level maternal and newborn care, community based newborn care), and the period of implementation (antenatal, intrapartum, post partum, newborn).

Table 1.

Description of maternal and neonatal intervention packages and components

| Intervention | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary level care, including outreach | |

| Antenatal care: | |

| Tetanus toxoid | Two tetanus toxoid Immunisations |

| Screening for pre-eclampsia | Blood pressure measurements for all pregnant women, urine test for proteinuria, and pre-referral care of women with pre-eclampsia or eclampsia |

| Screening and treatment | |

| Asymptomatic bacteriuria | Screening urine of all pregnant women at antenatal visits and treatment of bacteriuria with amoxicillin |

| Syphilis | Screening all pregnant women by rapid plasma reagin test and treatment of syphilis with benzathine penicillin |

| Skilled maternal care and immediate care of newborn (intrapartum): | |

| Normal delivery by skilled attendant | Includes safe delivery, cord care, identification of complications, first aid, and referral of complicated cases |

| Active management of third stage of labour | Administration of prophylactic oxytocin, cord clamping, and delivery of placenta by controlled cord traction |

| Initial management of post-partum haemorrhage | Management of postpartum haemorrhage with additional oxytocin, uterine massage, manual removal of placenta, repair of lacerations, and management of shock |

| Neonatal resuscitation | Detection of breathing problems and resuscitation of newborn when required |

| Referral level care | |

| Treatment of severe pre-eclampsia or eclampsia (antenatal and intrapartum)* | Inpatient care, including airway management, treatment with magnesium sulphate, treatment with antihypertensives, and care during labour when undelivered |

| Antibiotics for preterm premature rupture of membranes (antenatal and intrapartum)* | Administration of oral antibiotics to women with preterm premature rupture of membranes, and care during labour |

| Steroids for preterm births (antenatal and intrapartum)* | Administration of steroids and inpatient care of women with suspected preterm labour |

| Management of obstructed labour, breech presentation, and fetal distress* | External cephalic version for breech presentation; management of obstructed labour, persistent breech presentation, and fetal distress by operative delivery (vacuum extraction, forceps and vaginal breech delivery, and caesarean section) |

| Management of severe postpartum haemorrhage (intrapartum and post partum)* | Inpatient care of postpartum haemorrhage, including blood transfusion, treatment for shock, and hysterectomy |

| Management of maternal sepsis (intrapartum and post partum)* | Inpatient care of maternal sepsis, including treatment with intravenous or intramuscular antibiotics |

| Emergency neonatal care: | |

| Management of very low birthweight babies* | Inpatient care for very low birthweight babies, including special feeding support, additional warmth, close monitoring, and treatment with oxygen if necessary |

| Management of severe neonatal infections* | Inpatient care for severe neonatal infections, including treatment with intravenous or intramuscular antibiotics |

| Management of severe neonatal asphyxia* | Inpatient care for neonatal encephalopathy including treatment with oxygen |

| Management of neonatal jaundice* | Inpatient care for severe neonatal jaundice, including phototherapy |

| Community care of newborn | |

| Community newborn care package (first two components): | |

| Support for breastfeeding mothers (antenatal and neonatal) | Home visits to promote early and exclusive breast feeding provided by skilled care providers and community health workers |

| Support for low birthweight babies | Home visits to promote extra warmth for low birthweight babies and to support breastfeeding mothers provided by skilled care providers and community health workers |

| Community based management of neonatal pneumonia | Home visits for diagnosis and management of pneumonia in neonates and treatment with oral antibiotic therapy provided by community health workers |

Includes costs for transportation.

Intervention effects

The effectiveness of the interventions listed in table 1 and the estimated coverage levels in 2000 are listed in tables A and B on bmj.com. Effects are estimated through their impact on incidence, remission, and case fatality of the maternal and neonatal conditions specified in table D on bmj.com. We include the impact of interventions on maternal mortality and morbidity and on neonatal mortality, when available. A lack of reliable data prevents inclusion of the impact on neonatal morbidity or stillbirths, so the benefits of some interventions are under-estimated. Using the population model PopMod, we assessed the health effects on the population of the interventions compared with the no intervention scenario,11 with effects measured as the number of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) averted.

Intervention costs

The quantities of resources used for the interventions listed in table 1 are based on WHO evidence based guidelines12-15 as well as on information obtained from the studies used for the estimates of effectiveness (see table A on bmj.com), to ensure consistency between costs and effectiveness. When these could not be used, we sought expert opinion on the resources needed to introduce and run a programme. See table E on bmj.com for details on the costing methods and the main assumptions on use of resources.

Results

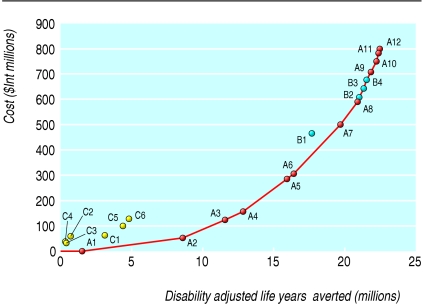

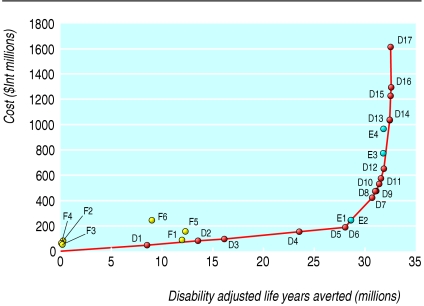

The costs, population health effects, and cost effectiveness for all 300 combinations of individual interventions analysed by WHO epidemiological subregions are available from www.who.int/choice. Tables F and G on bmj.com provide the full results for Afr-E (countries in sub-Saharan Africa with very high adult and high child mortality) and for Sear-D (countries in South East Asia with high adult and high child mortality). We present here the results of the most cost effective set of interventions. Tables 2 and 3 show the order in which interventions would be purchased at given levels of availability of resources, if cost effectiveness is the only consideration. This is called the “expansion path” (figs 1 and 2). The paper by Evans et al provides a detailed description on the construction and interpretation of the expansion path.10

Table 2.

Annual costs, effects, and cost effectiveness of intervention packages on optimal expansion path for Afr-E in 2000

| Intervention package | Description (coverage) of package | Yearly DALYs averted (millions) | Yearly cost ($Int millions) | ACER | ICER | Additional yearly resources required ($Int millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Community based management of neonatal pneumonia (95%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A2 | A1+community newborn care package (95%) | 9 | 58 | 7 | 8 | 57 |

| A3 | A2+tetanus toxoid (95%) | 12 | 125 | 11 | 22 | 67 |

| A4 | A3+ screening for pre-eclampsia, screening and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria, and screening and treatment of syphilis (95%) | 13 | 160 | 12 | 27 | 35 |

| A5 | A4+skilled maternal care and immediate care of newborn (95%) | 16 | 284 | 18 | 40 | 124 |

| A6 | A5+treatment of severe pre-eclampsia (95%) | 16 | 306 | 19 | 42 | 22 |

| A7 | A6+emergency neonatal care (95%) | 20 | 498 | 25 | 61 | 192 |

| A8 | A7+management of obstructed labour, breech presentation, and fetal distress | 21 | 589 | 28 | 73 | 91 |

| A9 | A8+steroids for preterm births (95%) | 22 | 706 | 32 | 117 | 117 |

| A10 | A9+management of maternal sepsis (95%) | 22 | 748 | 34 | 125 | 42 |

| A11 | A10+antibiotics for preterm premature rupture of membranes (95%) | 22 | 781 | 35 | 178 | 34 |

| A12 | A11+referral for postpartum haemorrhage (95%) | 22 | 801 | 36 | 223 | 19 |

DALY=disability adjusted life year; ICER=incremental cost effectiveness ratio; ACER=average cost effectiveness ratio; Afr-E=WHO defined region comprising countries in sub-Saharan Africa with very high adult and high child mortality.

Average gross domestic product per capita in Afr-E in 2000=Int$1576.

Community newborn care package=support for breastfeeding mothers and support for low birthweight babies.

Skilled maternal and immediate newborn care=normal delivery by skilled attendant, active management of third stage labour, initial management of postpartum haemorrhage, and neonatal resuscitation.

Emergency neonatal care=facility based care of very low birthweight babies, severe neonatal infections, severe neonatal asphyxia, and neonatal jaundice.

Table 3.

Annual costs, effects, and cost effectiveness of intervention packages on optimal expansion path for Sear-D in 2000

| Intervention package | Description (coverage) | Yearly DALYs averted (millions) | Yearly cost ($Int millions) | ACER | ICER | Additional yearly resources required ($Int millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | Support for breastfeeding mothers (50%) | 8 | 49 | 6 | 6 | 49 |

| D2 | Support for breastfeeding mothers (80%) | 14 | 80 | 6 | 6 | 31 |

| D3 | Support for breastfeeding mothers (95%) | 16 | 98 | 6 | 7 | 18 |

| D4 | Support for breastfeeding mothers+tetanus toxoid (80%) | 24 | 155 | 7 | 8 | 57 |

| D5 | Support for breastfeeding mothers+tetanus toxoid (95%) | 28 | 194 | 7 | 9 | 39 |

| D6 | Community care of newborn+tetanus toxoid (95%) | 28 | 195 | 7 | 20 | 1 |

| D7 | D6+normal delivery by skilled attendant+active management and initial treatment of postpartum haemorrhage (95%) | 31 | 426 | 14 | 88 | 231 |

| D8 | D7+screening for pre-eclampsia and screening for and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria (95%) | 31 | 476 | 15 | 123 | 49 |

| D9 | D8+community based management of neonatal pneumonia (95%) | 31 | 485 | 16 | 144 | 9 |

| D10 | D9+neonatal resuscitation+treatment of severe pre-eclampsia or eclampsia (95%) | 31 | 537 | 17 | 218 | 52 |

| D11 | D10+referral for postpartum haemorrhage (95%) | 32 | 571 | 18 | 261 | 34 |

| D12 | D11+management of maternal sepsis | 32 | 654 | 21 | 290 | 83 |

| D13 | D12+emergency neonatal care | 32 | 1039 | 32 | 614 | 385 |

| D14 | D13+screening and treatment of syphilis (95%) | 33 | 1049 | 32 | 699 | 9 |

| D15 | D14+management of obstructed labour, breech presentation, and fetal distress (95%) | 33 | 1234 | 38 | 2638 | 186 |

| D16 | D15+antibiotics for preterm premature rupture of membranes | 33 | 1299 | 40 | 2808 | 65 |

| D17 | D16+steroids for preterm births | 33 | 1619 | 50 | 16930 | 319 |

DALY=disability adjusted life year; ICER=incremental cost effectiveness ratio; ACER=average cost effectiveness ratio; Sear-D=WHO defined region comprising countries in South East Asia with high adult and child mortality.

Average gross domestic product per capita in Sear-D in 2000=$Int1449.

Emergency neonatal care=facility based care of very low birthweight babies, severe neonatal infections, severe neonatal asphyxia, and neonatal jaundice.

Fig 1.

Expansion path of most cost effective mix of interventions in Afr-E (countries in sub-Saharan Africa with very high adult and high child mortality) in 2000

Fig 2.

Expansion path of most cost effective mix of interventions in Sear-D (countries in South East Asia with high adult and high child mortality) in 2000

The expansion paths for both regions suggest that interventions for newborn care at the community level are highly cost effective (for example, promotion of breast feeding), followed by selected antenatal care interventions (for example, tetanus toxoid), interventions deliverable by a skilled attendant at birth in a health facility (for example, normal delivery care by a skilled attendant), then by more complex interventions that require referral to a higher level health facility. Important differences do, however, exist between the regions. Screening and treatment of syphilis in Sear-D is relatively less cost effective than in Afr-E owing to its lower prevalence. Community based management of neonatal pneumonia is relatively more cost effective in Afr-E than in Sear-D because of its higher prevalence.

The expansion path not only shows the relative cost effectiveness of interventions but also allows decision makers to see the absolute value of resources necessary to move to the next point on the expansion path. Sometimes, however, there may be insufficient resources to move to the next point. For example, if A9 is not affordable a decision maker may choose to implement a lower cost but less cost effective package such as B2 (referral care of postpartum haemorrhage), B3 (referral care of maternal sepsis and postpartum haemorrhage), or B4 (referral care of maternal sepsis and postpartum haemorrhage and antibiotics for preterm premature rupture of membranes). See tables H and I on bmj.com for further examples of alternative interventions for scaling up maternal and newborn health services in the event that the preferred intervention is unaffordable.

Considerable uncertainty surrounds the inputs used in this analysis, but rather than undertake a complex multivariate uncertainty analysis, for practical policy purposes we prefer to interpret the results by ICER (incremental cost effectiveness ratios) bands, using international dollars (a hypothetical unit of currency with the same purchasing power that the dollar has in the United States at a given time). For example, in Afr-E it is difficult to say with certainty that tetanus toxoid (ICER $Int22 per DALY averted) is more cost effective than other antenatal care interventions (ICER $Int27 per DALY averted). We can be more certain, however, that interventions costing less than $Int50 per DALY, such as community care of newborn babies, antenatal care (tetanus toxoid, screening for pre-eclampsia, screening and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria and syphilis), and skilled maternal and newborn care, are more cost effective than those costing more than $Int100 per DALY averted, such as antibiotics for preterm premature rupture of membranes. This means that the order in which the most cost effective interventions are introduced is up to the specific circumstances of a country. The important thing is to obtain high coverage with the group of cost effective interventions before implementing those of high cost and low effectiveness.

Eliminating discounting for health benefits resulted in about 2.5 times more DALYs averted, whereas removing age weighting decreased DALYs averted by 10-15% (data not shown). Costs were 5-20% higher without discounting. Although removing age weighting and discounting of DALYs favours interventions for newborn babies over those for mothers, the ranking of interventions and the expansion path, on the whole, remains the same.

Implementation of all the interventions covered in this analysis at 95% coverage would avert 52% of the year 2000 neonatal deaths and 51% of maternal deaths in Afr-E, and 56% of neonatal deaths and 51% of maternal deaths in Sear-D.

Discussion

Overall, community based and antenatal care packages to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality in two regions classified by the World Health Organization according to their epidemiological grouping (Ar-E, countries in sub-Saharan Africa with very high adult and high child mortality, and Sear-D, countries in South East Asia with high adult and high child mortality) were highly cost effective. However, it is only with accessible and good quality clinical services that most maternal and neonatal deaths will be averted—for example, skilled attendance to allow appropriate early recognition and treatment of complications, along with appropriate, timely referral to hospitals for more complex care. Although these services require considerably more resources than community based and antenatal care packages, they are effective in reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and, as such, are also highly cost effective. Sustained efforts to scale up coverage of skilled attendance at birth from the 44% in Afr-E and 28% in Sear-D (in 2000) are therefore crucial to meet the millennium development goals for maternal and child health (see table B on bmj.com). In addition, although increasing efforts have been directed towards improving antenatal coverage,4 implementation of key components such as tetanus toxoid remains suboptimal (51% in Afr-E and 77% in Sear-D). Furthermore, in regions where pneumonia is a leading cause of neonatal mortality, coverage of community based management of neonatal pneumonia is also low (13% in Afr-E).3 When availability of resources is unlikely to increase in the near future it may be worthwhile to scale down implementation of less cost effective interventions such as antibiotics for preterm premature rupture of membranes and antenatal steroids for preterm births (in Sear-D), and to reallocate these resources to more cost effective options such as community based newborn packages, selected antenatal care, and skilled attendance. This analysis has several strengths that increase the value of the information for decision making. Firstly, the methods explicitly account for the total cost of a package of interventions being often less than the sum of the costs of each component evaluated separately. On the whole, packages of maternal and newborn interventions proved more cost effective than individual interventions, largely due to synergies on costs. This highlights the importance of considering effective integration of services and implementation of maternal and newborn interventions in parallel, particularly those interventions with common delivery modes.

Secondly, the method allows the cost effectiveness of interventions that are currently implemented to be evaluated as well as those that could be introduced if new resources became available. It identifies whether the health of mothers and newborn babies could be improved by scaling down some interventions while scaling up others, even without additional resources.

As decisions on the allocation of resources are not based solely on considerations of cost effectiveness, the results presented here should not be used in a formulaic way, but rather cost effectiveness information should be considered alongside other health system goals such as equity and acceptability to stakeholders. Of particular importance is the need to consider the feasibility of implementing these interventions. Clinical services for maternal health, in particular, require well functioning health systems, appropriate human resources, timely referral systems, and institutional infrastructure.

In line with accepted practice for cost effectiveness studies, the resources used to provide the interventions were valued from an economic perspective. They should not therefore be interpreted as the extra cash that countries will have to pay to provide the intervention. But taking a financial perspective, the incremental costs of scaling up maternal and newborn health services, from the current coverage level of 43% with a limited package of care to 73% in 2015 with a full package of care, was estimated recently for 75 countries to require an initial investment of $0.22 (£0.12; €0.18) per capita in 2006 rising to $1.18 per capita by 2015.4

As with any cost effectiveness analysis, possible limitations of the analysis need to be carefully considered. Owing to the paucity of large scale effectiveness trials as well as the difficulty of measuring efficacy of some of the key interventions (particularly those done in combination), many of the interventions we analysed are based on limited efficacy trials or expert opinion. These sources of treatment efficacy are often derived from studies of good quality services provided by highly skilled professionals in developed settings, and caution needs to be exercised when extrapolating to less developed countries. In these circumstances, feasibility studies are recommended before wider implementation is undertaken. The lack of information on neonatal morbidity and stillbirths meant that we could only include the impact of interventions on neonatal mortality in the DALY estimates (although we were able to include the impact on maternal morbidity). As a result, our analysis underestimates the total benefits of some of the interventions.

Moreover, some interventions that are potentially beneficial were not included in this analysis. Exclusion of these interventions was largely due to a lack of information on either effectiveness of the intervention or disease burden necessary for cost effectiveness analysis, but this does not imply that they are cost ineffective. They include, among others, safe abortion, family planning, and surfactant therapy for respiratory distress syndrome.16-18 Several interventions, such as the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV, the prevention and treatment of malaria, maternal and infant supplementation with micronutrients and macronutrients, and vaccine preventable diseases are covered elsewhere in the series, as well as in previously published analyses for the WHO choosing interventions that are cost effective project.19-23 These other interventions should be delivered in an integrated manner along with the ones covered in this paper, to ensure a better coverage of care as well as to maximise on economies of scale and cost effectiveness.

What is already known on this topic

Over 500 000 women die during pregnancy or childbirth annually and more than 4 million babies die in the first 28 days of life

Most of these deaths can be averted by available and effective health interventions

What this study adds

Interventions at community and primary care levels to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality are highly cost effective, but current coverage is insufficient

Most hospital based interventions are also highly cost effective and without universal access to these the millennium development goals for maternal and child health will not be met

Universal access to the maternal and neonatal health interventions covered here would halve deaths in Afr-E and Sear-D

We found that while effective and efficient maternal and newborn health services are available at different resource levels, and that preventive, community based interventions are highly cost effective, universal access to the clinical facility based health services covered here are required to halve current levels of maternal and newborn mortality. These results agree with those recently advanced in a neonatal survival series3 and with available evidence for the cost effectiveness of single interventions—for example, promotion of breast feeding.24 Although the interventions covered here will go some way to achieving the millennium development goals for reducing child and maternal mortality (goals 4 and 5, respectively), they are by themselves not enough to reach the targets. A coordinated and intersectoral response with other child and reproductive health services as well as non-health sectors to reduce poverty and improve education is needed. Although not insubstantial resources are required, the interventions outlined here are highly cost effective, which highlights the importance of overcoming other barriers to attaining millennium development goals 4 and 5 such as strengthening of the health system and financial commitment as well as the moral and political will to do so.

Supplementary Material

Additional tables are on bmj.com

Additional tables are on bmj.com

We thank Lara Wolfson for technical input for modelling the effectiveness of tetanus toxoid intervention, Jeremy A Lauer for his input in modelling the effectiveness of the breastfeeding intervention, David B Evans for his comments on several drafts of this paper, Quazi Monirul Islam and Ornella Lincetto for their critical review of the inputs and results, and the other members of the WHO choosing interventions that are cost effective (CHOICE) Millennium Development Goals Team including Tessa Tan Torres-Edejer, Rob Baltussen, Ben Johns, Dan Chisholm, Josh Salomon, and Daniel Hogan.

Contributors: TA and SSL were responsible for the planning, conduct, analysis, and reporting of the work. SM contributed to the planning, conduct, and analysis of maternal interventions. ZAB and GLD were responsible for defining the effectiveness and coverage parameters for neonatal interventions as well the assumptions involved in costing. HF, MM, and JZ provided input on effectiveness and cost parameters for maternal interventions. All authors contributed to the selection of interventions. Other contributors include Luc de Bernis, Paul Van Look, Metin Gulmezoglu, Dale Huntington, and Joy Lawn, who served as expert panel to refine data inputs and assumptions required for the analysis. SSL prepared the first draft of the paper. Subsequent revisions were done by SSL and TA with input from all authors. TA and SSL are the guarantors. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily of the institutions they represent.

Funding: SSL and SM received funding from WHO for this work.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

This article is part of a series examining the cost effectiveness of strategies to achieve the millennium development goals for health

References

- 1.World Health Organization (Department of Reproductive Health and Research). Maternal mortality in 2000: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA. Geneva: WHO, 2004.

- 2.Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. 4 million neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why? Lancet 2005;365: 891-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, Adam T, Walker N, de Bernis L. Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet 2005;365: 977-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. The world health report 2005: make every mother and child count. Geneva: WHO, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Evans DB, Adam T, Tan-Torres Edejer T, Lim SS, Cassels A, Evans TG, et al. Achieving the millennium development goals for health: Time to reassess strategies for improving health in developing countries? BMJ 2005;331: 1133-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terris-Prestholt F, Watson-Jones D, Mugeye K, Kumaranayake L, Ndeki L, Weiss H, et al. Is antenatal syphilis screening still cost effective in sub-Saharan Africa. Sex Transm Infect 2003;79: 375-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffiths UK, Wolfson LJ, Quddus A, Younus M, Hafiz RA. Incremental cost-effectiveness of supplementary immunization activities to prevent neonatal tetanus in Pakistan. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82: 643-51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakhaee N, Mirahmadizadeh AR, Gorji HA, Mohammadi M. Assessing the cost-effectiveness of contraceptive methods in Shiraz, Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J 2002;8: 55-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans DB, Lim SS, Adam T, Tan-Torres Edejer T, the WHO-CHOICE Millennium Development Goals Team. Achieving the millennium development goals for health: Evaluation of current health intervention strategies and future priorities in developing countries. BMJ 2005. Nov 10; epub ahead of print (doi: 10.1136/bmj.38658.675243.94). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Evans DB, Tan-Torres Edejer T, Adam T, Lim S, the WHO-CHOICE Millennium Development Goals Team. Achieving the millennium development goals for health: Methods to assess the costs and health effects of interventions for improving health in developing countries. BMJ 2005;331: 1137-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lauer JA, Rohrich K, Wirth H, Charette C, Gribble S, Murray CJL. PopMod: a longitudinal population model with two interacting disease states. Cos Eff Resour Alloc 2003; 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.World Health Organization. Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth: a guide for midwives and doctors. WHO document WHO/RHR/00.7. Geneva: WHO, 2003.

- 13.World Health Organization. Pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum and newborn care: a guide for essential practice. Geneva: WHO, 2003. [PubMed]

- 14.World Health Organization. Managing newborn problems: a guide for doctors, nurses and midwives. Geneva: WHO, 2003.

- 15.World Health Organization. WHO antenatal care randomized trial: manual for the implementation of the new model. WHO document WHO/RHR/01.30. Geneva: WHO, 2002.

- 16.Stevens TP, Blennow M, Soll RF. Early surfactant administration with brief ventilation vs selective surfactant and continued mechanical ventilation for preterm infants with or at risk for respiratory distress syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;3: CD003063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulier R, Gumodoka AM, Hofmeyr GJ, Cheng LN, Campana A. Medical methods for first trimester abortion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;2: CD002855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nanda G, Switlick K, Lule E. Accelerating progress towards achieving the MDG to improve maternal health: a collection of promising approaches. Health, Nutrition and Population (HNP) discussion paper. Washington, DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the World Bank, 2005.

- 19.Baltussen R, Knai C, Sharan M. Iron fortification and iron supplementation are cost-effective interventions to reduce iron deficiency in four subregions of the world. J Nutr 2004;134: 2678-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan-Torres Edejer T, Aikins M, Black R, Wolfson L, Hutubessy R, Evans DB. Achieving the millennium development goals for health: Cost effectiveness analysis of strategies in developing countries for child health. BMJ 2005. Nov 10; epub ahead of print (doi: 10.1136/bmj.38652.550278.7C ). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Baltussen R, Floyd K, Dye C. Achieving the millennium development goals for health: Cost effectiveness analysis of strategies for tuberculosis control in developing countries. BMJ 2005. Nov 10; epub ahead of print (doi: 10.1136/bmj.38645.660093.68). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Morel C, Lauer J, Evans DB. Achieving the millennium development goals for health: Cost effectiveness analysis of strategies to combat malaria in developing countries. BMJ 2005. Nov 10; epub ahead of print (doi: 10.1136/bmj.38639.702384.AE). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Hogan DR, Baltussen R, Hayashi C, Lauer JA, Salomon JA. Achieving the millennium development goals for health: Cost effectiveness analysis of strategies to combat HIV/AIDS. BMJ 2005. Nov 10; epub ahead of print (doi: 10.1136/bmj.38643.368692.68). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Horton S, Sanghvi T, Phillips M, Fiedler J, Perez-Escamilla R, Lutter C, et al. Breastfeeding promotion and priority setting in health. Health Policy Plan 1996;11: 156-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.