Abstract

Hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum) accumulates benzoxazinones (Bxs) as defensive compounds. Previously, we found that five Bx biosynthetic genes, TaBx1-TaBx5, are located on each of the three genomes (A, B, and D) of hexaploid wheat. In this study, we isolated three homoeologous cDNAs of each TaBx gene to estimate the contribution of individual homoeologous TaBx genes to the biosynthesis of Bxs in hexaploid wheat. We analyzed their transcript levels by homoeolog- or genome-specific quantitative RT-PCR and the catalytic properties of their translation products by kinetic analyses using recombinant TaBX enzymes. The three homoeologs were transcribed differentially, and the ratio of the individual homoeologous transcripts to total homoeologous transcripts also varied with the tissue, i.e., shoots or roots, as well as with the developmental stage. Moreover, the translation products of the three homoeologs had different catalytic properties. Some TaBx homoeologs were efficiently transcribed, but the translation products showed only weak enzymatic activities, which inferred their weak contribution to Bx biosynthesis. Considering the transcript levels and the catalytic properties collectively, we concluded that the homoeologs on the B genome generally contributed the most to the Bx biosynthesis in hexaploid wheat, especially in shoots. In tetraploid wheat and the three diploid progenitors of hexaploid wheat, the respective transcript levels of the TaBx homoeologs were similar in ratio to those observed in hexaploid wheat. This result indicates that the genomic bias in the transcription of the TaBx genes in hexaploid wheat originated in the diploid progenitors and has been retained through the polyploidization.

Keywords: biosynthetic genes, homoeolog, polyploidization

Benzoxazinones (Bxs), major secondary metabolites in gramineous plants including wheat (Triticum aestivum), rye (Secale cereale), and maize (Zea mays), are involved in the chemical defense of plants against pathogens and insects (1, 2). The major Bxs are 2,4-dihydroxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one (DI-BOA) and its 7-methoxy analog (DIMBOA), which are constitutively present in the vacuole as glucosides (DIBOA-Glc and DIMBOA-Glc). The Bx-glucosides, whose amount reaches the maximum soon after germination and decreases thereafter to a constantly low level, are particularly important in defense during the juvenile stage of plant growth (3, 4).

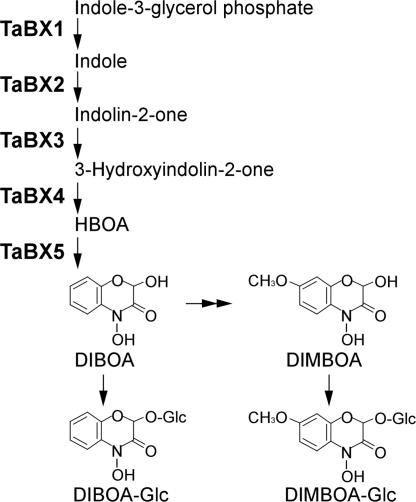

The biosynthetic pathway of Bxs branches off from that of tryptophan at indole-3-glycerol phosphate (5-8). Previously, we isolated five genes responsible for the Bx biosynthesis, TaBx1-TaBx5, from hexaploid wheat (9, 10). They are orthologous to the Bx1-Bx5 in maize (5, 11) and the HlBx1-HlBx5 in wild barley, Hordeum lechleri (12). A TaBX1 enzyme is involved in the conversion of indole-3-glycerol phosphate to indole, whereas TaBX2-TaBX5, which are cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs) belonging to the CYP71C subfamily, catalyze the successive oxidation reactions from indole to DIBOA (Fig. 1). DIMBOA was suggested to be synthesized by the hydroxylation and methylation at the C7-position of DIBOA, and a corresponding hydroxylase gene (Bx6) has been cloned in maize (13).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the Bx biosynthetic pathway showing enzymatic reactions catalyzed by the gene products of TaBx1-TaBx5 in hexaploid wheat.

Hexaploid bread wheat (T. aestivum, 2n = 6x = 42, genome constitution AABBDD) is an allopolyploid that was formed through hybridization and successive chromosome doubling of three ancestral diploid species (2n = 14), T. urartu (AA), Aegilops speltoides (SS≒BB), and Ae. squarrosa (DD) (14, 15). Chromosome mapping using aneuploid lines of hexaploid wheat revealed that the TaBx1 and TaBx2 genes coexist on homoeologous group-4 chromosomes, 4A, 4B, and 4D, and that the TaBx3, TaBx4, and TaBx5 genes are clustered on group-5 chromosomes, 5A, 5B, and 5D (10). The orthologs of TaBx1-TaBx5 also were found in the three ancestral diploid species (9, 10).

It is of great interest to reveal how the expressions of homoeologous genes are regulated in hexaploid wheat. Although all three homoeologs of the majority of genes are assumed to be expressed in hexaploid wheat (16), it has been known that some homoeologous genes suffer from epigenetic silencing or that their gene expressions are altered during the polyploidization of wheat (16-19). This finding indicates that in hexaploid wheat we cannot reveal the degrees of contributions of the three genomes to the expression of a gene simply based on the expression level of individual homoeologous genes in the three diploid progenitors. Several studies have shown the unequal transcriptions of the three homoeologs of certain genes in hexaploid wheat (20-22). To our knowledge, however, no information is available on the differential transcriptions of the respective three homoeologs of multiple genes involved in the same metabolic pathway in hexaploid wheat. Moreover, there has been no comparative study both on the transcript levels of the three homoeologs of a gene and on the properties of their translation products in hexaploid wheat. The five genes involved in the Bx biosynthesis of hexaploid wheat are excellent targets for a study to reveal how the expressions of individual homoeologous genes are regulated in a complex metabolic pathway in polyploids, because all three homoeologous loci of those genes have been demonstrated to be retained in hexaploid wheat (10).

In this study, we investigated the transcript levels of the three homoeologs of TaBx1-TaBx5, and the enzymatic properties of their translation products, and estimated the contributions of the respective three homoeologs (or genomes) to the Bx biosynthesis in the young seedlings of hexaploid wheat. We also analyzed the transcript levels of their homoeologs in tetraploid wheat and in the three diploid progenitors of hexaploid wheat to reveal how the expression of the TaBx genes changed during the polyploid evolution of wheat.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials. A cultivar of hexaploid wheat (T. aestivum, 2n = 6x = 42, genomes AABBDD), Chinese Spring (CS), was used for cDNA cloning, genomic PCR, and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). We conducted the chromosomal assignment of the three homoeologous cDNAs of the TaBx1-TaBx5 genes by genomic PCR analysis using six lines of ditelosomic (DT) stocks of CS (DT4AL, DT4BS, DT4DS, DT5AL, DT5BL, and DT5DL) (23) and two (5BS-6 and 5BL-11) of the deletion stocks of CS (24). We also used an extracted tetraploid CS line that had been generated from a cross between CS and a tetraploid wheat (Tetra CS, 2n = 4x = 28, AABB) (25) for qRT-PCR analysis. For Northern blot analysis we used three diploid progenitors (2n = 14) of hexaploid wheat, T. urartu (Kyoto University seed stock accession no. KU199-6, genome AA), Ae. speltoides (accession no. KU5727, SS) and Ae. squarrosa (accession no. KU20-9, DD). All seed stocks used in this study were supplied by National BioResource Project-Wheat (Japan, www.nbrp.jp). Seeds were germinated and grown as described in ref. 9.

Preparation of Substrates for Enzyme Assay. Indole-3-glycerol phosphate was synthesized enzymatically from CdRP [1-(2-carboxyphenylamino)-1-deoxyribulose 5′-phosphate] by recombinant indole-3-glycerol phosphate synthase expressed in Escherichia coli (for details, see Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). 3-Hydroxyindolin-2-one, 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one, DIBOA, DIMBOA, DIBOA-Glc, and DIMBOA-Glc were prepared as described in ref. 9.

Isolation of Three Homoeologous cDNAs. We constructed a cDNA library of the 30-h-old CS shoots using the Uni-ZAP XR vector (Stratagene) and screened it with the TaBx1-TaBx5 cDNAs that had been isolated previously (9, 10). The full-length cDNAs were labeled with the AlkPhos Direct Labeling Kit (Amersham Biosciences). The plaque-lifted membrane was hybridized and washed at 55°C according to the manufacturer's instructions. The hybridization signal was generated with ECF (Amersham Biosciences) and detected with the FLA-2000 (Fujifilm). After the secondary screening, we randomly selected 20 positive clones for each TaBx gene and sequenced them.

Chromosomal Assignment of Three Homoeologous cDNAs. To determine the homoeoalleles from which the three homoeologous cDNAs were transcribed, we designed primers that would specifically amplify each of the cDNA homoeologs of TaBx1-TaBx5 genes that had been isolated from CS cDNA library. The forward primer sequences having interhomoeologous SNP sites at the 3′ ends were unique to the respective homoeologs, and the reverse ones were common to all homoeologs (see Fig. 5 and Table 3, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). To achieve homoeolog- or genome-specific amplification, we conducted PCR under highly stringent conditions as follows: 2 min at 94°C, followed by 40 cycles of amplification (30 s at 94°C, 1 min at 68°C) in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 50 ng of genomic DNA, 0.2 μM primers, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1.2 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 units of Platinum TaqDNA polymerase (Invitrogen). Aliquots (5 μl) of the mixture were electrophoresed on 2% (wt/vol) agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. Three homoeologous cDNAs were assigned to the respective chromosome arms (4AS, 4BL, and 4DL for TaBx1 and TaBx2 genes, and 5AS, 5BS, and 5DS for TaBx3-TaBx5 genes) based on the presence or absence of the PCR products in the CS aneuploid lines.

qRT-PCR Analysis. Total RNA was purified from the shoots and roots of 36-h-old (h36) and 5-day-old (d5) seedlings of CS and Tetra CS by using an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). After DNase treatment, RNA was purified again with an RNeasy column. Single-stranded cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA by using oligo(dT) primer with the Thermo Script RT-PCR system (Invitrogen) in a 20-μl reaction mixture. The qPCR was carried out with an Applied Biosystems PRISM 7000 sequence detection system by using 1 μl (equivalent to 50 ng) of the cDNA mixture as templates under the same conditions as described above except that the reaction mixture contained SYBR Green I. Fixed quantities of the cloned cDNAs were used for generating the standard curves for fluctuations of the respective cDNA homoeologs.

Expression and Purification of TaBX Enzymes. The TaBx1 cDNA homoeologs were inserted into pET24b vector (Novagen) to be expressed in E. coli. The recombinant TaBX1 enzymes were expressed and purified as described in Supporting Text. The TaBX2-TaBX5 enzymes encoding membrane-bound cytochrome P450s were expressed in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). The coding sequences of the three homoeologs of TaBx2-TaBx5 were separately inserted into HindIII site of the vector pAAH5N (26), and the vector was introduced into S. cerevisiae AH22 strain. The culture of transformed yeast cells, preparation of recombinant microsome fractions, and determination of P450 contents were performed as described in ref. 9.

Enzyme Assay. The activity of the recombinant TaBX1 enzymes was measured in 0.1 M Tris·HCl buffer (pH 7.8) containing 1 mg/ml BSA, 0.04-0.5 μg of the enzyme, and 10-400 μM indole-3-glycerol phosphate in a final volume of 150 μl. The enzyme quantity and reaction time were set appropriately so that the reaction proceeded linearly. After incubation at 37°C, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 30 μl of n-propanol, and the product indole was quantified by HPLC [column, Wakosil II 5C18 HG (4.6 × 150 mm); elution, 20-80% (vol/vol) MeOH gradient (0-15 min) in 0.1% (vol/vol) HOAc; flow rate, 0.8 ml/min; temperature, 40°C; detection, 270 nm]. The activity of TaBX2, TaBX3, TaBX4, and TaBX5 enzymes was measured by using their respective substrates, indole, indolin-2-one, 3-hydroxyindolin-2-one, and 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one, as described in ref. 9. Apparent Michaelis constants (Km) and maximum velocities (Vmax) were determined from [s] vs. [s]/v plot.

Northern Analysis. Total RNA was isolated from the shoots and roots of h36 and d5 seedlings of diploid species by the AGPC (acid guanidium-phenol-chloroform) method (27). Total RNA (20 μg each) was electrophoresed on a 1% (wt/vol) agarose gel with 1× Mops buffer (pH 7.0) containing 2.2 M formaldehyde and was blotted onto Hybond N+ membrane. The membrane was hybridized with 32P-labeled cDNA probes (TaBx1A, TaBx2A, TaBx3A, TaBx4A, and TaBx5A) in Church buffer (pH 7.2) (28) at 65°C for 16 h. The membrane was washed at 65°C twice in 2× SSPE buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS for 15 min and once in 1× SSPE buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS for 30 min. The washed membrane was autoradiographed with an imaging plate (Fujifilm) and analyzed with the FLA-2000.

Extraction and HPLC Analysis of Bxs. We extracted Bxs from the seedlings of CS, Tetra CS, T. urartu, Ae. speltoides, and Ae. squarrosa every 12 h from 24 to 120 h after seeding. Shoots and roots excised from the seedlings were frozen in liquid nitrogen and were separately ground to a fine powder with a mortar and a pestle, followed by the extraction of Bxs with HOAc-MeOH (2:98, vol/vol). The extract was passed through a filter (Millex LG, Millipore) and subjected to HPLC [column, Wakosil II 5C18 HG (4.6 × 150 mm); elution, 22% (vol/vol) MeOH in 0.1% (vol/vol) HOAc; flow rate, 0.8 ml/min; temperature, 40°C; detection, 280 nm].

Results

Isolation and Chromosomal Assignment of the Three Homoeologous cDNAs of the Five TaBx Genes. We screened the CS cDNA library and isolated three kinds of homoeologous cDNA for each of the five TaBx genes (Table 1), including the TaBx cDNAs isolated previously (9, 10). The genomic PCR with the primer combinations TaBx1A5-2/TaBx1Co3-3, TaBx1B5-3/TaBx1Co3-3, and TaBx1D5-2/TaBx1Co3-3 amplified no PCR products in DT4AL, DT4BS, and DT4DS, respectively (see Fig. 6A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). This result indicated that the TaBx1A, TaBx1B, and TaBx1D cDNAs were transcribed from the alleles on 4AS, 4BL, and 4DL, respectively. The chromosomal origins of the other homoeologous TaBx cDNAs were revealed in the same manner (see Fig. 6 B-E and Table 1). Two paralogous loci each for TaBx3 (on 5BS and 5BL) and for TaBx5 (both on 5BS) are located on chromosome 5B (10). The fact that the TaBx3B-specific primers amplified PCR products in 5BL-11 (Fig. 6C) indicated that the TaBx3B cDNA was transcribed from the locus on 5BS, not 5BL. The absence of PCR amplification in 5BS-6 with the TaBx5B-specific primers (Fig. 6E) indicated that the TaBx5B cDNA was transcribed from the more distal locus of the two TaBx5 loci on 5BS. The TaBx3 and TaBx5 homoeologs at the other paralogous loci on 5B are probably not transcribed or at least are transcribed little because no corresponding cDNAs were isolated in the cDNA library screening.

Table 1. Three homoeologous cDNAs of TaBx1-TaBx5 genes isolated from CS.

| Gene name | Chromosome arm location | CYP no. | Protein length (amino acids) | Accession no.* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaBx1A | 4AS | —† | 319 | AB094060‡ |

| TaBx1B | 4BL | —† | 319 | AB124849 |

| TaBx1D | 4DL | —† | 318 | AB124850 |

| TaBx2A | 4AS | CYP71C9v1 | 528 | AB042630§ |

| TaBx2B | 4BL | CYP71C9v2 | 528 | AB042631§ |

| TaBx2D | 4DL | CYP71C9v3 | 528 | AB124851 |

| TaBx3A | 5AS | CYP71C7v2 | 527 | AB042628§ |

| TaBx3B | 5BS | CYP71C7v3 | 527 | AB124853 |

| TaBx3D | 5DS | CYP71C7v1 | 527 | AB124852 |

| TaBx4A | 5AS | CYP71C6v2 | 528 | AB124854 |

| TaBx4B | 5BS | CYP71C6v3 | 528 | AB124855 |

| TaBx4D | 5DS | CYP71C6v1 | 528 | AB042627§ |

| TaBx5A | 5AS | CYP71C8v2 | 523 | AB042629§ |

| TaBx5B | 5BS | CYP71C8v1 | 524 | AB124856 |

| TaBx5D | 5DS | CYP71C8v3 | 523 | AB124857 |

The cDNA homoeologs of the TaBx genes showed a striking similarity in nucleotide sequence, ranging between 94.0% and 98.3% (see Table 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). They were also very similar in deduced amino acid sequences, ranging from 95.2% to 98.9%. Like the TaBx2-TaBx5 cDNAs isolated previously (9), the TaBx2-TaBx5 homoeologs isolated in this study had the heme-binding motif that is conserved near the C-termini of P450 enzymes (29). We deposited the amino acid sequences to obtain cytochrome P450 monooxygenase numbers (Table 1) from David Nelson (http://drnelson.utmem.edu/CytochromeP450.html).

Catalytic Activity of the TaBX Enzymes. The three recombinant TaBX1 enzymes expressed in E. coli were successfully purified from solubilized inclusion bodies. Microsome fractions of the recombinant yeast with each of the TaBx2-TaBx5 cDNA homoeologs showed the maximum absorption at 448 nm in reduced CO-difference spectra (data not shown). This result indicated that all homoeologs of the TaBx2-TaBx5 cDNAs were expressed as active P450 enzymes.

The kinetic parameters of the TaBX1-TaBX5 enzymes were determined (Table 2). The Km values of TaBX1-TaBX4 differed slightly between the three homoeologs, from 1.4-fold between TaBX4A and TaBX4D to 1.9 fold between TaBX2A and TaBX2B. Conversely, the Km value of TaBX5A was ≈13 and 16 times larger than that of TaBX5B and TaBX5D, respectively. On average, the Km values of TaBX2 and TaBX3 were smaller than those of the other TaBX enzymes. The difference in kcat value between the three homoeologs ranged from 2-fold between TaBX2A/B and TaBX2D to 13-fold between TaBX5A and TaBX5D. The average kcat value was the highest for TaBX1 and the lowest for TaBX5 enzymes. The kcat/Km values indicated that TaBX1B, TaBX2D, TaBX3A, TaBX4B, and TaBX5D had the highest reaction efficiency among the three homoeologs of the respective TaBX enzymes.

Table 2. Kinetic constants of the TaBX1-TaBX5 enzymes.

| Enzyme | Km, μM | kcat, s−1 | kcat/Km, s−1/mM |

|---|---|---|---|

| TaBX1A | 82 | 0.887 | 11 |

| TaBX1B | 45 | 8.325 | 185 |

| TaBX1D | 53 | 3.631 | 69 |

| TaBX2A | 3.2 | 0.078 | 24 |

| TaBX2B | 1.7 | 0.078 | 46 |

| TaBX2D | 2.2 | 0.160 | 73 |

| TaBX3A | 2.7 | 0.181 | 67 |

| TaBX3B | 4.6 | 0.215 | 47 |

| TaBX3D | 3.4 | 0.040 | 12 |

| TaBX4A | 38 | 0.047 | 1.2 |

| TaBX4B | 32 | 0.124 | 3.9 |

| TaBX4D | 28 | 0.047 | 1.7 |

| TaBX5A | 188 | 0.0008 | 0.0043 |

| TaBX5B | 14 | 0.0029 | 0.21 |

| TaBX5D | 12 | 0.010 | 0.83 |

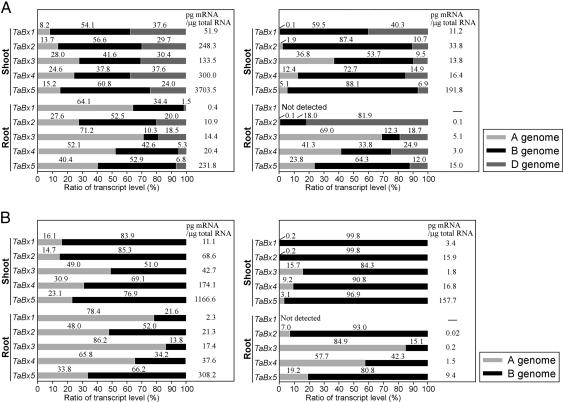

Transcript Levels of the Three Homoeologous TaBx Genes in Hexaploid Wheat. We investigated the transcript profiles of the three homoeologs of the TaBx1-TaBx5 genes in h36 and d5 CS seedlings by the genome-specific qRT-PCR (Fig. 2A). Both in shoots and roots, the TaBx5 homoeologous genes had the highest transcript levels, and the TaBx1 homoeologous genes had the lowest. The transcript levels of the TaBx genes in roots were much lower than those in the shoots. The transcripts of the TaBx1-TaBx5 decreased in amount from 36 h to 5 days after seeding both in shoots and in roots. The decrease was more evident for TaBx1 and TaBx2 than for TaBx3-TaBx5 in roots.

Fig. 2.

Transcript profiles of individual homoeologs of the TaBx1-TaBx5 genes in the h36 (Left) and d5 (Right) seedlings of CS (A) and Tetra CS (B). The ratios of the amounts of transcripts of the individual homoeologs to the total amounts of homoeologous transcripts are plotted.

The biased transcription of the three homoeologs was observed for all TaBx genes. In the h36 shoots, the transcript levels were in descending order of B-genome homoeolog, D-genome homoeolog, and A-genome homoeolog for all TaBx1-TaBx5 genes. In the d5 shoots, the A- and D-genome homoeologs were transcribed relatively less, and the B-genome homoeologs were transcribed relatively more, with the exception of relatively higher levels of TaBx1D and TaBx3A.

In the h36 plants, the ratio of transcripts to the total homoeologous transcripts (simply called “the ratio” hereafter) of the transcripts of the A-genome homoeologs was higher, and the ratio of the D-genome homoeologs was lower in the roots than in the shoots. The ratios of the A- and D-genome homoeologs in the d5 roots were similar to those in the h36 roots, in contrast to their time-dependent decrease in the shoots, with the exception of TaBx2.

Transcript Levels of the Two Homoeologous TaBx Genes in Tetraploid Wheat. The transcript level of each homoeolog of the TaBx genes in the Tetra CS seedlings was analyzed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 2B). As observed in CS, TaBx5 showed the highest transcript level and TaBx1 showed the lowest in both shoots and roots, with the exception of lower transcription of TaBx3 than TaBx1 in the d5 shoots. The total amount of the transcripts was generally smaller than that of hexaploid CS except for the h36 roots.

The transcript profile of the A- and B-genome TaBx homoeologs in Tetra CS was similar to that in CS. In the h36 shoots, every homoeolog of the TaBx genes was transcribed more in the B-genome than in the A-genome, and the ratio of the transcript levels of A-genome homoeologs was higher than that of the B-genome homoeologs in the roots than in the shoots. In the d5 shoots, the ratio of the transcripts of the A-genome homoeologs decreased greatly, and the transcripts of the B-genome homoeologs accounted for almost the entire TaBx transcripts. In contrast, the ratio of the transcripts of A-genome homoeologs in TaBx3 and TaBx4 remained unchanged in the h36 and the d5 roots, and the transcripts of the A-genome TaBx2 and TaBx5 homoeologs decreased moderately with age in the roots compared with that in the shoots. In the roots, during the period from 36 h to 5 days after seeding, the TaBx1 and TaBx2 transcripts decreased more rapidly than the TaBx3-TaBx5 transcripts.

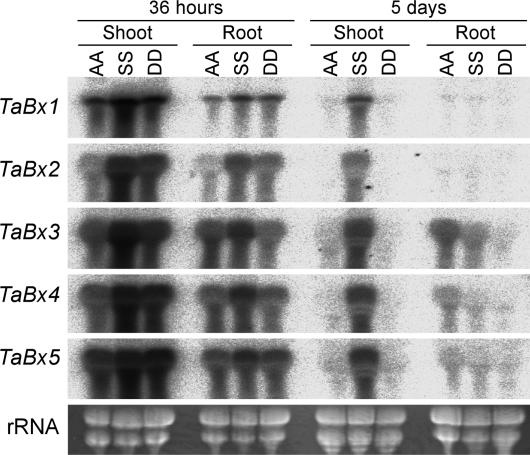

Transcript Levels of the TaBx Homoeologs in Diploid Wheats. We investigated the transcript levels of the TaBx genes in the three diploid progenitors of hexaploid wheat to reveal whether the differential transcript levels of the three homoeologs in hexaploid wheat reflect the respective transcription of those in diploid species (Fig. 3). The transcript profiles in the three diploids resembled those in the three genomes of hexaploid wheat. In the h36 shoots, the five TaBx genes were strongly transcribed in all diploid species. For every TaBx gene the transcript level was in the order of Ae. speltoides (SS≒BB) > Ae. squarrosa (DD) > T. urartu (AA). In the d5 shoots, the transcript levels of the A- and D-genome species decreased to a trace, whereas the S-genome species retained the high transcript level.

Fig. 3.

Northern blot analysis using the h36 and d5 seedlings of diploid wheats with the TaBx1-TaBx5 probes. AA, SS, and DD represent T. urartu, Ae. speltoides, and Ae. squarrosa, respectively. Ethidium bromide-stained rRNA is used as a loading control.

In the h36 roots, the transcript level of every TaBx gene was the highest in the S-genome species. This result is slightly different from the cases of CS and Tetra CS in which the A-genome homoeologs were predominantly transcribed for the TaBx1, TaBx3, and TaBx4 genes. In the d5 roots, TaBx3 and TaBx4 were transcribed slightly higher in the A-genome species than in the S- and D-genome species, just like the A-genome TaBx3 and TaBx4 homoeologs were transcribed slightly more than the B- and D-genome homoeologs in CS and Tetra CS. As observed in the d5 roots of CS and Tetra CS, the transcripts of TaBx1 and TaBx2 genes decreased to traces in all diploid species.

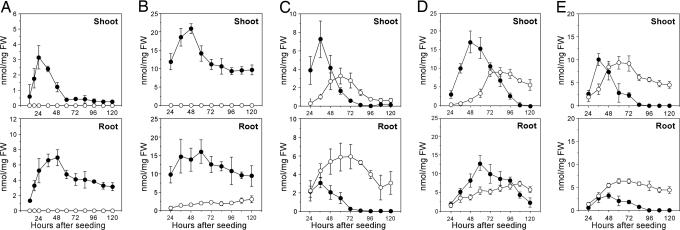

Fluctuation in the Amount of Bxs. In all wheat species and strains investigated, the Bxs increased soon after germination and gradually decreased to a constantly low level with the decrease in the transcript levels of the TaBx genes (Fig. 4). Either of the Bxs, DIBOA or DIMBOA, became predominant, depending on the species, tissue, and developmental stage.

Fig. 4.

Changes in the amounts of Bxs in the seedlings of T. urartu (A), Ae. speltoides (B), Ae. squarrosa (C), Tetra CS (D), and CS (E). Filled circle, DIBOA-Glc; open circle, DIMBOA-Glc. The average values of three to five replications are plotted together with SD (±SD).

In both shoots and roots on all stages, Ae. speltoides accumulated more Bxs than T. urartu and Ae. squarrosa (Fig. 4 A-C). This finding is consistent with the fact that the TaBx genes were transcribed constantly higher in Ae. speltoides than in T. urartu and Ae. squarrosa (Fig. 3), except for the d5 roots.

In both shoots and roots, the total amount of Bxs in CS was slightly less than or similar to that in Tetra CS (Fig. 4 D and E). This result is inconsistent with the fact that the TaBx genes were constantly transcribed more in CS than in Tetra CS except for the h36 roots.

Discussion

Contribution of the Three Genomes of Hexaploid Wheat to the Bx Biosynthesis Was Estimated from Difference in the Transcript Level and Catalytic Property. Polyploidization is accompanied by changes in genome structure and gene expression, including the loss of gene sequences, silencing, and down-/up-regulation of some homoeologs (16-19, 30-39). We found that the loci of the five Bx biosynthetic genes are retained in all three genomes of hexaploid wheat (10) and isolated three homoeologous cDNAs each for TaBx1-TaBx5 genes in this study, showing that neither the loss nor the epigenetic silencing of the TaBx genes had occurred during the polyploidization.

Because of the high degree of nucleotide identity among the three homoeologs of all TaBx genes in hexaploid wheat, we cannot separately detect the transcripts of individual homoeolog by hybridization-based methods such as Northern or cDNA microarray analysis. We developed a genome-specific qRT-PCR method and analyzed the transcript levels of the three homoeologs of each of the five TaBx genes. To our knowledge, this work presents a previously unreported analysis of the transcript levels of three homoeologs that encode the enzymes catalyzing sequential reactions involving a metabolic pathway in hexaploid wheat.

The transcript levels of the three homoeologs were different for all TaBx genes. In addition, the catalytic activity of the TaBX1-TaBX5 enzymes differed, depending on the homoeolog. This result suggests that the ratio of transcript levels of the three homoeologs (Fig. 2) does not directly represent their contribution to the Bx biosynthesis. TaBX1B, TaBX2D, TaBX3A, TaBX4B, and TaBX5D showed the highest reaction efficiency (kcat/Km) among the three homoeologs and therefore should have contributed to the Bx biosynthesis much more than expected from the amount of their transcripts. For example, of the total transcripts of TaBx1 genes in the h36 seedlings, TaBx1A, TaBx1B, and TaBx1D, respectively, accounted for 8.2%, 54.1%, and 37.6% in shoots and for 64.1%, 34.4%, and 1.5% in roots. The reaction efficiency (kcat/Km) of TaBX1B is ≈17 times and 3 times higher than those of TaBX1A and TaBX1D, respectively. Thus, we can estimate that TaBX1B contributes much more to the reaction than the other two homoeologous enzymes in both shoots and roots. Moreover, the extremely low kcat/Km value of the TaBX5A enzyme (50 and 190 times lower than TaBX5B and TaBX5D) made the A-genome contribution to the biosynthetic reaction negligible, although TaBx5A was substantially transcribed. We can safely assume that the B-genome generally contributes the most to the Bx biosynthesis in hexaploid wheat.

There are some studies demonstrating the difference in the level of transcripts among homoeologs in polyploid plants (20-22, 35, 38). However, there have been no studies on the proteins encoded by individual homoeologs. The slight difference in amino acid sequence caused a great difference in the enzymatic properties of the homoeologous TaBX enzymes. Thus, both efficiency of gene transcription and performance of the gene products need to be considered in the estimation of the contribution of different genomes to certain biochemical processes in allopolyploids.

Variation of Genome-Specific Transcripts in Hexaploid Wheat Originated in the Diploid Progenitors. In allopolyploids no global genomic bias in gene expression has been reported, and therefore genomes in which preferentially expressed homoeoalleles exist are implied to be different from gene to gene (35). However, we found that the ratio of the genome-specific transcripts fluctuated in a similar manner in general for all of the TaBx1-TaBx5 genes. Namely, the transcription of the TaBx genes in the same genome seems to be controlled in a coordinated way.

In the shoots, the same TaBx genes in CS, Tetra CS, and three diploid species showed similar patterns of time-dependent changes in the transcript levels according to homoeologs (Figs. 2 and 3). In addition, time-dependent decreases in the transcript level in roots were more drastic in TaBx1 and TaBx2 than in TaBx3, TaBx4, and TaBx5 in all wheats. These facts suggest that the genomic bias in terms of the transcription of the TaBx genes in hexaploid wheat originated in the diploid progenitors and has been retained through the polyploidization.

Discrepancy Between the Levels of Bxs and the TaBx Transcripts Implies an Intergenomic Regulation of Gene Expression. In the three diploid species, the transcript levels of the TaBx genes directly correlated with the amount of Bxs, although the predominant Bx was different from species to species (Fig. 4 A-C). In the h36 shoots and in the d5 shoots and d5 roots, the amounts of the TaBx transcripts were higher in CS than in Tetra CS, but in the d5 shoots and d5 roots the Bx production in CS was similar to that in Tetra CS. This discrepancy might be explained in terms of the reduction of translation efficiency caused by the increase of the TaBx transcripts in hexaploid wheat. Polyploidization might increase total transcription of genes, but, conversely, it might cause reduction in translation by some mechanisms, like small RNA-mediated or homology-dependent gene silencing as observed in plants with an overexpressing transgene homologous to the endogenous gene (40, 41).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Chihiro Tanaka for instrumental support in DNA sequencing; Dr. Toshiyuki Sakaki and Raku Shinkyo for instrumental support and helpful suggestions in measuring absorption spectra of P450 proteins; and Dr. Shuhei Nasuda for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Radioisotope Research Center, Kyoto University, for instrumental support in radioisotope experiments. This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research No. 16000377 (to T.N.).

Author contributions: T.N. and H.I. designed research; T.N. and R.C.Y. performed research; T.N. and A.I. analyzed data; and T.N., A.I., and T.R.E. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: Bx, benzoxazinone; CS, Chinese Spring; DIBOA, 2,4-dihydroxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one; DIMBOA, 7-methoxy analog of DIBOA; DT, ditelosomic; qRT-PCR, quantitative RT-PCR; h36, 36-h-old; d5, 5-day-old.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. AB124849-AB124857).

References

- 1.Niemeyer, H. M. (1988) Phytochemistry 27, 3349-3358. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sicker, D., Frey, M., Schulz, M. & Gierl, A. (2000) Int. Rev. Cytol. 198, 319-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakagawa, E., Amano, T., Hirai, N. & Iwamura, H. (1995) Phytochemistry 38, 1349-1354. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebisui, K., Ishihara, A., Hirai, N. & Iwamura, H. (1998) Z. Naturforsch. 53c, 793-798. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frey, M., Chomet, P., Glawischnig, E., Stettner, C., Grün, S., Winklmair, A., Eisenreich, W., Bacher, A., Meeley, R. B., Briggs, S. P., et al. (1997) Science 277, 696-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frey, M., Stettner, C., Paré, P. W., Schmelz, E. A., Tumlinson, J. H. & Gierl, A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 14801-14806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melanson, D., Chilton, M.-D., Masters-Moore, D. & Chilton, W. S. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 13345-13350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gierl, A. & Frey, M. (2001) Planta 213, 493-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nomura, T., Ishihara, A., Imaishi, H., Endo, T. R., Ohkawa, H. & Iwamura, H. (2002) Mol. Genet. Genomics 267, 210-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nomura, T., Ishihara, A., Imaishi, H., Ohkawa, H., Endo, T. R. & Iwamura, H. (2003) Planta 217, 776-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frey, M., Kliem, R., Saedler, H. & Gierl, A. (1995) Mol. Gen. Genet. 246, 100-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grün, S., Frey, M. & Gierl, A. (2005) Phytochemistry 66, 1264-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frey, M., Huber, K., Park, W. J., Sicker, D., Lindberg, P., Meeley, R. B., Simmons, C. R., Yalpani, N. & Gierl, A. (2003) Phytochemistry 62, 371-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang, S., Sirikhachornkit, A., Faris, J. D., Su, X., Gill, B. S., Haselkorn, R. & Gornicki, P. (2002) Plant Mol. Biol. 48, 805-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang, S., Sirikhachornkit, A., Su, X., Faris, J., Gill, B., Haselkorn, R. & Gornicki, P. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 8133-8138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wendel, J. F. (2000) Plant Mol. Biol. 42, 225-249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kashkush, K., Feldman, M. & Levy, A. A. (2002) Genetics 160, 1651-1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He, P., Friebe, B. R., Gill, B. S. & Zhou, J.-M. (2003) Plant Mol. Biol. 52, 401-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Islam, N., Tsujimoto, H. & Hirano, H. (2003) Proteomics 3, 549-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Himi, E. & Noda, K. (2004) J. Exp. Bot. 55, 365-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mochida, K., Yamazaki, Y. & Ogihara, Y. (2003) Mol. Genet. Genomics 270, 371-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Podkowinski, J., Jelenska, J., Sirikhachornkit, A., Zuther, E., Haselkorn, R. & Gornicki, P. (2003) Plant Physiol. 131, 763-772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sears, E. R. & Sears, L. M. S. (1978) in Proceedings of the Fifth International Wheat Genetics Symposium, ed. Ramanujam, S. (Indian Society of Genetics and Plant Breeding, New Delhi), pp. 389-407.

- 24.Endo, T. R. & Gill, B. S. (1996) J. Heredity 87, 295-307. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang, Y. F., Furuta, Y., Nagata, S. & Watanabe, W. (1999) Genes Genet. Syst. 74, 67-70. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oeda, K., Sakaki, T. & Ohkawa, H. (1985) DNA 4, 203-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chomczynski, P. & Sacchi, N. (1987) Anal. Biochem. 162, 156-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Church, G. M. & Gilbert, W. (1984) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81, 1991-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuler, M. A. (1996) Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 15, 235-284. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Comai, L., Tyagi, A. P., Winter, K., Holmes-Davis, R., Reynolds, S. H., Stevens, Y. & Byers, B. (2000) Plant Cell 12, 1551-1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, H.-S. & Chen, Z. J. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 6753-6758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozkan, H., Levy, A. A. & Feldman, M. (2001) Plant Cell 13, 1735-1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaked, H., Kashkush, K., Ozkan, H., Feldman, M. & Levy, A. A. (2001) Plant Cell 13, 1749-1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madlung, A., Masuelli, R. W., Watson, B., Reynolds, S. H., Davison, J. & Comai, L. (2002) Plant Physiol. 129, 733-746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams, K. L., Cronn, R., Percifield, R. & Wendel, J. F. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 4649-4654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kashkush, K., Feldman, M. & Levy, A. A. (2003) Nat. Genet. 33, 102-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osborn, T. C., Pires, J. C., Birchler, J. A., Auger, D. L., Chen, Z. J., Lee, H.-S., Comai, L., Madlung, A., Doerge, R. W., Colot, V., et al. (2003) Trends Genet. 19, 141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams, K. L., Percifield, R. & Wendel, J. F. (2004) Genetics 168, 2217-2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, J., Tian, L., Madlung, A., Lee, H.-S., Chen, M., Lee, J. J., Watson, B., Kagochi, T., Comai, L. & Chen, Z. J. (2004) Genetics 167, 1961-1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pickford, A. S. & Cogoni, C. (2003) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 60, 871-882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams, K. L. & Wendel, J. F. (2005) Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 8, 135-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.