Abstract

The adaptive immune system relies on rare cognate lymphocytes to detect pathogen-derived antigens. Naïve lymphocytes recirculate through secondary lymphoid organs in search of cognate antigen. Here, we show that the naïve-lymphocyte recirculation pattern is controlled at the level of innate immune recognition, independent of antigen-specific stimulation. We demonstrate that inflammation-induced lymphocyte recruitment to the lymph node is mediated by the remodeling of the primary feed arteriole, and that its physiological role is to increase the efficiency of screening for rare antigen-specific lymphocytes. Our data reveal a mechanism of innate control of adaptive immunity: by increasing the pool of naïve lymphocytes for detection of foreign antigens via regulation of vascular input to the local lymph node.

To mount protective immunity, the adaptive immune system relies on the detection of foreign antigens by rare lymphocytes possessing appropriate antigenic specificity. After local infection, antigens from the pathogen are taken up by dendritic cells (DCs) (1). Concomitant recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) by the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) induces DC activation and migration into the draining lymph nodes (dLNs), where they present antigenic peptides on MHC molecules to naïve T lymphocytes (1–3). TLR-mediated recognition of PAMPs is required for the initiation of Th1 immunity (4–7), and incorporation of TLR agonists in vaccine adjuvants is often required for the generation of robust adaptive immunity. TLR signals contribute to the generation of adaptive immunity by several distinct mechanisms including the activation of antigen presenting cells (APC) (2) and stromal cells (7). TLR pathways are also required for the activation of adaptive responses by blocking the suppressive effect of regulatory T cells (8).

A major unresolved mystery of the adaptive immune system relates to how the rare cognate lymphocytes are screened for specificity toward pathogen-derived antigens in a timely manner. Although several in vivo studies have elegantly demonstrated the dynamic interactions of naïve cognate T cells and antigen-loaded DCs in the lymph node (LN) (9–12), to visualize such events, these experimental approaches often require introduction of a large number of lymphocytes bearing a specific T cell receptor. In a naïve mouse, each LN contains ≈106 cells, of which only 1 in 106 to 105 has the specificity for a given antigen. This screening process represents a daunting task for the antigen-presenting DC to seek out the rare cognate lymphocytes within the dLN. We hypothesized that a mechanism must exist that facilitates the search for cognate lymphocytes within the secondary lymphoid organs. In this regard, the encounter of cognate T cells with the APC can be enhanced in the dLN by several mutually nonexclusive processes. These include increases in (i) the motility of the APC and/or T cells within the dLN, (ii) the retention of naïve lymphocytes in the dLN, and (iii) the recruitment of additional naïve lymphocytes to the dLN. The latter two processes would result in cellular accumulation and enlargement of the dLN. Thus, we propose that an important immunological purpose of the LN hypertrophy is to facilitate screening for cognate lymphocytes during the initiation of adaptive immune responses. Moreover, in the face of invasion by a replicating pathogen, the search for lymphocytes that recognize the appropriate microbial peptides must occur rapidly to provide the host with survival advantage. Thus, we hypothesize that such a process must be inducible upon infection and regulated by the innate immune system.

In the present study, we tested these hypotheses using a combination of approaches involving minimal TLR agonists and a physiologically relevant model of mucosal viral infection with herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2). We report that during the initiation of an adaptive immune response, a large number of naïve lymphocytes are recruited specifically to the LNs draining the site of immunization or infection, a process we call “inflammation-induced recirculation.” We demonstrate that inflammation-induced naïve lymphocyte recruitment to the dLN occurs via remodeling of the primary arteriole feeding the LN to a larger diameter, and that its physiological role is to increase the efficiency of screening for rare antigen-specific lymphocytes.

Methods

Cells, Viruses, and Reagents. Thymidine kinase mutant HSV-2 strains 186TKΔKpn (13) were used to infect mice. Depo-Provera-treated female mice were infected intravaginally (ivag) with 106 PFU of HSV-2 or with uninfected Vero cell lysate (mock infection) as described in ref. 14. All antibodies were obtained from eBioscience. All other reagents were from Sigma, unless otherwise indicated.

Mice. Female C57BL6 × 129 F2, C57BL6, and BALB/c mice, 6–8 wk old, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. TLR9-/- (15) or TLR2-/- (16) mice were bred and maintained in our facilities under standard conditions. All procedures used in this study complied with federal guidelines and institutional policies set by the Yale animal care and use committee.

Immunization. TLR agonists CpG (50 μg) or LPS (5 μg) were injected into the hind footpad with or without OVA323–339 peptide in saline (Fig. 1A) or in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA) (Fig. 1B). Four days later, popliteal LNs were collected and analyzed.

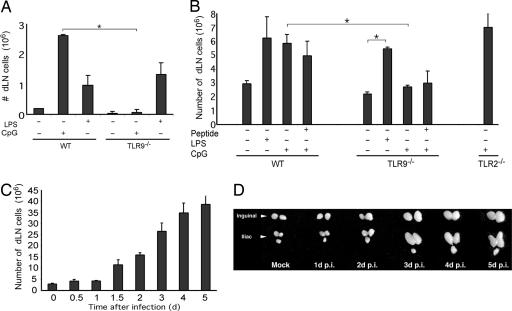

Fig. 1.

TLR agonists alone are sufficient to induce LN hypertrophy. (A) The number of cells in popliteal LN was measured in WT or TLR9-/- mice (n = 4 per condition) 4 days after footpad injection of TLR ligands in saline. (B) The number of cells in popliteal LN was measured in WT, TLR9-/-, or TLR2-/- mice (n = 3 per condition) 4 days after footpad injection of TLR ligands with or without OVA323–339 peptide in IFA. (C) The total cell number of dLNs (inguinal and iliac) after ivag HSV-2 (106 PFU) infection was measured at the indicated time points. (D) Photographic depiction of dLNs of HSV-2-infected mice. Similar results were obtained in five separate experiments. *, P < 0.05, significant difference between the indicated groups.

Measurement of Cell Proliferation. Mice were continuously fed BrdUrd at a concentration of 0.8 mg/ml in their drinking water for the duration of infection. All dLNs (inguinal and iliac) were harvested, and cell suspensions were stained for BrdUrd and surface lymphocyte markers according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Pharmingen). For analysis of DNA content, dLNs were harvested at indicated time points after HSV-2 infection, and single cells were labeled with propidium iodide according to a standard protocol. The percentage of cells incorporating propidium iodide at 2N (G1) or 4N (G2/M) was determined by flow cytometry according to the manufacturer's instructions (Becton Dickinson).

Adoptive Transfer. Single-cell suspensions were prepared from the LNs of WT or CD62L-/- mice. The cells were labeled with 0.5 μM carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimdyl ester (CFSE) (Molecular Probes), and 107 cells were transferred into the lateral tail vein of the recipient mice. Mice were infected 2 h after adoptive transfer and killed at 4 days postinfection (p.i.). In some experiments, the donor lymphocytes were pretreated with 200 ng/ml pertussis toxin for 45 min at 37°C, extensively washed, and labeled with CFSE before transfer at -1 day or +2 days of infection. The rates of lymphocyte entry were assessed by injecting 107 CFSE-labeled syngeneic naïve donor lymphocytes into mice that have been infected with HSV-2 for 2 days or 5 days and collecting dLNs (inguinal and iliac) and nondraining lymph nodes (ndLNs) (axillary and cervical) 2 h later. The rate of entry was calculated as the number of CFSE+ lymphocytes in the LN per hour. For OT-II transfer experiments, recipient C57BL6 mice were injected with 104, 105, 106, or 107 OT-II TCR-transgenic CD4+ T cells i.v., followed by immunization in the hind footpad with 100 μg of ovalbumin and 4 μg of LPS emulsified in IFA. CD4+ T cells were isolated from the dLNs (popliteal) at the indicated time points, and 105 dLN CD4+ T cells were restimulated for 72 h in vitro with 2 × 105 irradiated syngeneic splenocytes in the presence or absence of 1 μM OVA323–339 peptide. Cytokines were measured by ELISA.

Intravital Microscopy. These experiments were modeled after the method described by von Andrian (17) and evaluated with procedures as described in ref. 18 (see Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Statistical Analyses. All statistical analyses were performed with sigmastat 2.03 (SPSS, Chicago). Paired t tests and two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance were used to evaluate the effects of treatment, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Innate Signals Are Sufficient to Induce Lymph Node Hypertrophy. To test our hypothesis that selective accumulation of naïve lymphocytes to the dLN would facilitate screening for cognate lymphocytes during the initiation of an immune response, and that such process must be induced rapidly by the innate immune system, we first examined the nature of the stimulus required to promote cellular accumulation in the dLN. Specifically, we asked whether cellular accumulation depends on antigen, TLR signals, or both. Mice were injected s.c. with LPS or CpG, agonists for TLR4 and TLR9, respectively. This procedure resulted in LN hypertrophy and an increase in cellularity (Fig. 1A). Importantly, inoculation of TLR agonist alone induced cellular accumulation in the dLNs, revealing the sufficiency of innate signals in this process. These responses required the presence of a specific TLR, because mice deficient in TLR9 failed to accumulate cells in the dLNs after CpG injection. To test the contribution of the antigen-specific T cells in LN hypertrophy, an antigenic peptide OVA323–339 was co-injected with TLR agonists (Fig. 1B). Because productive activation of naïve T cells requires prolonged antigen exposure (19), these agents were emulsified in IFA. Although inoculation of IFA alone resulted in a measurable LN hypertrophy, LPS and CpG induced significant TLR-dependent increase in cellularity in the dLN (Fig. 1B). Importantly, inclusion of a highly immunogenic peptide did not result in additional increase in cellularity in the 4 days after injection. Thus, TLR-mediated innate recognition of PAMPs alone is sufficient to trigger LN hypertrophy, and antigen-specific T cell responses are not required for this process. How can this antigen-independent PAMP-induced accumulation of lymphocytes contribute to the generation of adaptive immunity?

To address this question in the context of a physiological infection, we used a mouse model of genital herpes. Ivag infection of mice with HSV-2 represents an ideal model to dissect immune inductive mechanisms because the location and the kinetics of cell-mediated immune responses have been well defined (14, 20, 21). We confirmed that hypertrophy occurs in the inguinal and iliac LNs draining the infected genital mucosa, both in terms of the increase in cellularity (Fig. 1C) and gross organ enlargement (Fig. 1D). Thus, we decided to use this model of physiological mucosal HSV-2 infection to address key questions regarding how adaptive immune responses are initiated within the defined sets of dLNs.

Inflammation Induces Recruitment of Nondividing Naïve Lymphocytes to the dLN. Because TLR agonists alone are sufficient to induce LN hypertrophy, this process likely reflects the accumulation of non-specific naïve lymphocytes rather than antigen-induced proliferation. To determine whether the increase in cellularity is caused by the proliferation of lymphocytes within the dLNs or accumulation of nondividing lymphocytes, we gave mice a continuous dose of BrdUrd and measured the number of proliferating lymphocytes in the dLNs after ivag HSV-2 infection. There was a marked increase in all lymphocyte subsets. We found that >95% of the cells found in the dLNs at 4 days p.i. were nondividing lymphocytes (Fig. 2A). This finding was also confirmed by measuring DNA content in the dLN cells by propidium iodide staining at various time points after HSV-2 infection (Fig. 2B). Thus, these data indicated that LN hypertrophy occurs as a result of the accumulation of nondividing lymphocytes and is not due to the proliferation of activated lymphocytes.

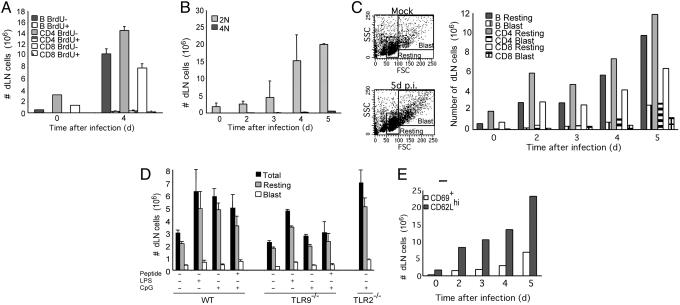

Fig. 2.

dLN enlargement is caused by the accumulation of nonproliferating, resting naïve lymphocytes. (A) Cumulative BrdUrd incorporation by lymphocytes in the dLNs (inguinal and iliac) during 4 days of HSV-2 infection was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of BrdUrd+ vs. BrdUrd- lymphocyte subsets. (B) The number of dividing cells was determined by propidium iodide labeling of the dLN cells at the indicated time points after HSV-2 infection. Each bar represents an average of five mice in each group. (C) The resting vs. blast phenotype of the dLN cells after HSV-2 infection was assessed by forward scatter vs. side scatter analysis of the lymphocyte subsets. (D) The number of resting vs. blast cells in popliteal LN was measured in WT, TLR9-/-, or TLR2-/- mice (n = 3 per condition) 4 days after footpad injection of TLR agonists in IFA with or without OVA323–339 peptide (100 μg) as in Fig. 1B. (E) dLN cells from HSV-2-infected mice were collected and analyzed for surface expression of CD69 and CD62L. The bar depicts the number of CD69+ and CD62Lhi cells at various time points after infection. These data are representative of three similar experiments. *, P < 0.05, significant difference between control and infected groups.

The nature of the nondividing lymphocytes that accumulate in the dLNs early postinfection was further examined. The majority of these cells had a small resting naïve lymphocyte phenotype (Fig. 2C), even at the peak of HSV-2-specific Th1 responses (14). Similarly, small resting lymphocytes constituted the majority of the dLN cells after TLR agonist inoculation (Fig. 2D). To confirm the activation status of these small resting lymphocytes, they were analyzed for several cell surface markers for naïve and activated lymphocytes. The majority of the lymphocytes in the dLNs were CD62Lhi and CD69- until day 5 after HSV-2 infection (Fig. 2E). Similar accumulation of naïve resting lymphocytes was observed in the dLNs of mice infected ivag with HSV-1, as well as postimmunization with antigen emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant (see Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These data suggested that LN hypertrophy in general is due to the accumulation of naïve lymphocytes.

Naïve lymphocyte accumulation can be mediated by increase in their retention or recruitment to the dLN. To test whether greater numbers of naïve lymphocytes are recruited from the peripheral blood, we examined the rate of lymphocyte entry into the dLNs. CFSE-labeled naïve lymphocytes were injected i.v. into mice that had been infected with HSV-2 for 2 or 5 days, and the rate of entry into iliac and inguinal nodes was measured (Fig. 3). The rate of entry of the transferred naïve lymphocytes into the dLNs increased steadily, reaching a 5-fold increase by day 5 p.i. compared with that of noninfected mice or to the ndLNs of the infected mice (Fig. 3A). The rate of entry was proportional to the total cellularity in the dLN or the ndLN (Fig. 3B). Thus, these data indicated that during the first few days of priming, there is a dramatic increase in the rate of naïve lymphocyte recruitment from the peripheral blood pool, consistent with previous observations (22–25). Thus, the recirculation pattern of the naïve lymphocytes is significantly altered so as to recruit more naïve lymphocytes selectively to the LNs draining the site of infection. Moreover, because naïve resting lymphocytes constitute the majority of the dLN cells after TLR agonist inoculation (Fig. 2D), innate recognition of PAMPs is sufficient to induce this altered recirculation.

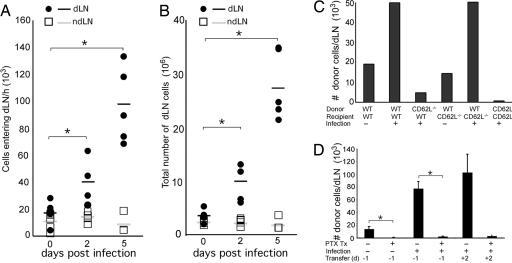

Fig. 3.

Inflammation-induced recirculation utilizes CD62L and Giα-dependent pathway. The rate of cell entry into the dLN was measured by adoptive transfer of CFSE-labeled naïve lymphocytes into mice at days 2 and 5 after HSV-2 infection. Two hours later, cells were collected from either the dLNs or ndLNs, and the number of CFSE+ cells (A) and the total number of cells (B) were measured. Each bar represents an individual mouse. Data are representative of two separate experiments. (C) Lymphocytes from WT or CD62L-/- mice were labeled with CFSE and adoptively transferred into WT or CD62L-/- recipients. Mice were either infected or not infected with HSV-2 ivag, and 4 days later, CFSE+ cells were enumerated in the dLNs. Data represents the average number of cells per dLN. (D) Donor lymphocytes were treated with pertussis toxin or with PBS, labeled with CFSE, and adoptively transferred to mice at -1 day or +2 days p.i. with HSV-2. The number of CFSE+ donor cells was analyzed in the dLN at 4 days p.i. and plotted as the average number of donor cells per dLN. These data are representative of three similar experiments. *, P < 0.05.

Inflammation-Induced Recirculation Occurs via the High Endothelial Venule (HEV). To determine the molecular requirement for the inflammation-induced recirculation, we examined the entry of naïve lymphocytes deficient in specific molecules known to be involved in homeostatic recirculation. During homeostatic recirculation, naïve lymphocytes enter the LNs by transendothelial migration across the HEVs (26, 27). This process requires (i) the interaction of CD62L with its ligand, molecules collectively known as the peripheral node addressins (PNAd), and (ii) the stimulation of cells through the chemokine receptor CCR7 by chemokines (CCL19 and CCL21), which induces conformational changes in the integrins such as LFA-1 (26). Whereas WT lymphocytes migrated into the LNs draining HSV-2 infection site, those lacking CD62L failed to accumulate in the dLNs (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, pretreatment of naïve lymphocytes by pertussis toxin, an inhibitor of Giα signaling, rendered cells incapable of accumulating into the dLNs (Fig. 3D). These data showed that inflammation-induced recirculation requires both CD62L and chemokine responsiveness through G protein-coupled receptors.

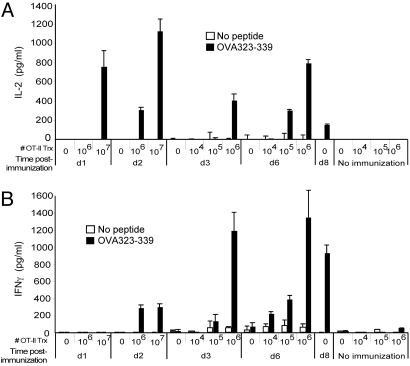

The Cognate Lymphocyte Number Controls the Onset of Th1 Immunity. Our data indicated that local LNs are designed to collect a large number of naïve lymphocytes during the initiation of an immune response. A major potential advantage of such a system is that by allowing more naïve lymphocytes to specifically survey the LNs draining the site of infection, it provides a larger repertoire from which to screen for lymphocytes with specificity to the microbial antigens. Because only 1 in 106 to 105 lymphocytes has the specificity for a given antigen, selective increase in the total number of naive lymphocytes in the dLNs would facilitate the screening process for cognate lymphocytes. This would provide a significant immunological advantage because unchecked pathogen replication can proceed exponentially in the infected host, and the survival of the host critically depends on the timely generation of effector responses. To test whether the total number of naive cognate CD4+ lymphocytes in the dLNs affects the onset of Th1 immunity, we examined the time course of Th1 generation in mice that had been injected with defined numbers of antigen-specific CD4+ T lymphocytes. Mice were adoptively transferred with 104, 105, 106, or 107 OT-II TCR-transgenic CD4+ T cells and subsequently immunized in the footpad with ovalbumin plus LPS in IFA. CD4+ T cells from the dLNs were isolated at various time points and restimulated in vitro with irradiated syngeneic splenocytes in the presence or absence of the cognate OVA323–339 peptide. We found that the onset of the effector cytokine secretion by CD4+ T cells depended on the number of OT-II cells transferred (Fig. 4). Mice that received 107 OT-II cells generated an IL-2 response in the dLNs as early as 1 day postimmunization. The onset of IFN-γ secretion occurred as early as day 2 postimmunization in mice receiving 106 or 107 OT-II cells, whereas those that received 105 OT-II cells had a delay in the onset of effector responses until day 6. Mice that did not receive OT-II cells failed to induce Th1 response until day 8 postimmunization. These data indicated that the time required to generate Th1 response is inversely proportional to the number of cognate lymphocytes present in the LN. Thus, an immunological purpose of the inflammation-induced recirculation is to facilitate the induction of adaptive immune responses by increasing the total number of naïve lymphocytes that enter and survey the incoming antigens within the dLNs.

Fig. 4.

The total number of cognate T cells determines the onset of Th1 responses. C57BL6 mice injected i.v. with the indicated number of OT-II CD4+ T cells were immunized in the hind footpad with ovalbumin (100 μg) and LPS (4 μg) in IFA. dLN CD4+ T cells were restimulated and assayed for IL-2 (A) and IFN-γ (B) secretion in the presence (filled bar) or absence (open bar) of OVA323–339 peptide. Data are representative of four similar experiments.

Mechanism of Inflammation-Induced Recirculation. Enhanced recruitment of naïve lymphocytes into dLNs can be mediated by a change in the ability of the HEV to allow immigration of more naïve lymphocytes per given surface area and/or by an increase in vascularity (28) leading to increase in the number of HEVs. To this end, we examined the number and size of the HEVs in the dLNs. Quantitative analysis of serial tissue sections revealed that although the density of HEVs in the dLNs stayed constant, the total number of HEVs in the dLN increased proportional to the LN size (see Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These results indicated that the increased input of naïve lymphocytes to the dLN is at least in part mediated by a rapid increase in the number of HEVs. We reasoned that the increase in lymphocyte recruitment through additional HEVs must be achieved by an increase in blood supply into the LNs, as suggested by previous studies in larger animals (24, 29, 30). If so, the arteriole feeding the dLN must expand to accommodate an increase in blood flow.

To test this hypothesis, we measured the diameter of the arteriole feeding the inguinal LN by intravital microscopy. This analysis revealed that by day 3 p.i., the arteriole feeding the inguinal LN was enlarged by nearly 50% (Fig. 5A, Resting). The increase in vessel diameter can be caused by either a loss of basal tone or by structural remodeling of the arteriole. To distinguish these possibilities, we examined the effect of local administration of a nitric oxide (NO) donor, SNP, which induces maximal vessel dilation. If the feed arteriole of the dLN was simply dilated because of loss of tone, the SNP-induced maximal diameters will be the same between the infected and the control groups. However, after SNP administration, the arteriole feeding the dLN in the infected mice exhibited greater maximum diameter (161 ± 3 μm) compared with the control (128 ± 5 μm), indicating that arteriolar enlargement occurred as a result of vascular remodeling (Fig. 5A, +SNP).

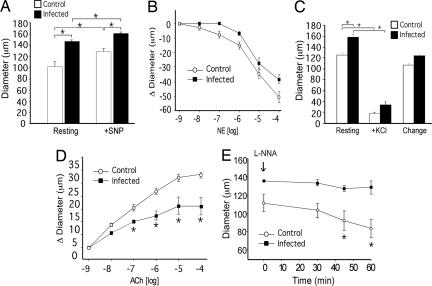

Fig. 5.

Inflammation-induced recirculation occurs through remodeling of the arteriole feeding the dLN. The internal vessel diameter of the primary arteriole feeding the dLN was measured in naïve or HSV-2-infected mice at 3 days p.i. by using intravital microscopy. (A) Resting and maximal (+SNP) diameters of the arteriole proximal to dLN in noninfected control (open bar; n = 7) vs. infected (filled bar; n = 5) mice. (B) Vasoconstriction of the arteriole after application of varying doses of norepinephrine (NE). (C) Smooth muscle function of the arteriole feeding the dLN was measured in uninfected control (n = 6) and HSV-2-infected (n = 5) mice. Maximal vasoconstriction was measured after depolarization of vascular smooth muscle with potassium chloride. Change is calculated as the difference between resting and KCl treatment. (D) Vasodilatation of the arteriole was measured after administration of varying doses of ACh. (E) The effect of NOS inhibition by Nω-nitro-l-arginine (L-NNA) on vascular diameter was assessed over time. Data represent mean diameter (A, C, and E) or change in diameter (B and D) ± SEM. *, P < 0.05.

Vascular remodeling can result in altered function of the arteriolar smooth muscle cells and/or the endothelial cells. The nature of adaptation was investigated by topical administration of agonists that are selective for respective cell types. Vasoconstriction to norepinephrine (a smooth muscle agonist) revealed normal responsiveness of the arteriolar smooth muscle cells (Fig. 5B). Moreover, depolarization of smooth muscle cells with KCl demonstrated similar, dramatic arteriolar constriction in both infected and control mice (Fig. 5C). Collectively, these data indicated that the smooth muscle function in the enlarged dLN arteriole is not affected by inflammation. To examine whether remodeling was associated with altered endothelial cell function, responses to ACh (endothelium-dependent vasodilator via NO production) were evaluated. Remarkably, the arteriole feeding the dLN underwent much reduced dilation in response to ACh, contrasting with the pronounced vasodilation observed in control mice (Fig. 5D). This reduced responsiveness to ACh by the dLN feed arteriole suggested that the endothelial cells are defective in NO production. To test for the constitutive activity of endothelial NOS, Nω-nitro-l-arginine (an inhibitor of NOS) was administered topically. Unlike the progressive vasoconstriction observed in control mice, arteriole of the infected mice failed to constrict in response to Nω-nitro-l-arginine (Fig. 5E), indicating a defect in NO synthesis by the dLN arteriolar endothelium. Collectively, these results revealed that a rapid remodeling and expansion of the primary feed vessel to the dLN takes place during the initiation of the adaptive immune responses, and that this process is accompanied by the modification of the vascular endothelial but not smooth muscle function.

Discussion

Owing to their strategic location and architectural design (31), the LNs serve as optimal site for the induction of adaptive immune responses. Naïve lymphocytes recirculate through the LNs in search of cognate antigens. Upon infection, DCs are activated by recognition of PAMPs and are induced to migrate from the site of infection to the LN via the afferent lymph (1). After interaction with activated DCs, antigen-specific T cells are preferentially retained within the LN by down-regulating their sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor (32). This process prevents cognate T cells from exiting via the efferent lymph, thus allowing them to maintain contact with the APC. Such prolonged interactions with the APC induce T cells to undergo proliferation and differentiation into effector cells. However, although these events become detectable within the dLN after 5 days p.i., in animals with a natural TCR repertoire, the majority of the cells that constitute the hypertrophic LN at earlier time points were naïve resting lymphocytes (Fig. 2). Here, we showed that through the recruitment of a large number of naïve lymphocytes, the LN allows productive surveillance and rapid induction of effector responses. This altered recirculation of the naïve lymphocytes is induced by innate signals alone (Fig. 1) and leads to an increase in the rate of naïve lymphocyte entry specifically to the dLN (Fig. 3). Furthermore, enhanced recruitment of naïve lymphocytes is mediated by remodeling of the arteriole feeding the LN to a larger diameter (Fig. 5), which will increase the blood flow and delivery of circulating lymphocytes.

Our study demonstrates a process by which the innate immune recognition of pathogens controls the generation of adaptive immune responses via remodeling of the arteriolar vessel. According to the Poiseuille–Hagen equation, the volumetric flow rate through a cylindrical blood vessel is proportional to the forth power of the vessel radius. Thus, with constant arterial perfusion pressure, the increase in arteriolar diameter from 101 ± 9 μm (naïve) to 147 ± 3 μm (day 3 p.i.) leads to a 4.5-fold increase in the rate of naïve lymphocyte flow rate through the dLNs. This conclusion is consistent with an earlier study showing that there is a 4-fold increase in the cardiac output into the LN draining the site of inflammation at 3 days after oxazolone painting (22). Thus, the net capacity for naïve cognate lymphocyte screening increases from 3 × 106 per LN per day (17) to 14 × 106 per LN per day after 3 days of infection (see calculation in Supporting Text). Whereas transient reduction in the egress of lymphocytes, or “lymphocyte shutdown,” occurs within 6–18 h after challenge, cell output in the efferent lymph actually rises rapidly, reaching a 3-fold increase over the steady-state levels by day 3 (33). Thus, the gross effect of the contribution of the enlarged arteriole in cell input to the dLN is likely underestimated because of the mass egress via the efferent lymph. Combined with the 10-fold increase in the total number of lymphocytes in the local dLNs at day 3 p.i. (Fig. 1), the increase in the total number of lymphocytes that transit the relevant LNs greatly enhances the chance for encounter of naïve lymphocytes with cognate antigens. Consistent with this interpretation, by artificially introducing differing numbers of cognate lymphocytes, we show that indeed the increase in the total number of cognate CD4+ T lymphocytes dramatically accelerates the onset of Th1 response induction. Because s.c. injected antigens reach the dLNs within 15–30 min (34, 35), with ample cognate T cells in the LN, a Th1 response developed within 48 h of immunization with ovalbumin and LPS (Fig. 4). These results indicated that the rate-limiting step in the generation of Th1 effector responses is not the time required for naïve T cells to undergo activation and differentiation but, rather, the time required for the rare lymphocytes to find their cognate antigen presented by the appropriate DCs in the LN.

The enlargement of the regional LN is a hallmark of infection with a variety of pathogens, and as with any other biologically important processes, it is likely mediated by multiple mechanisms invoked by innate stimuli. After bacterial challenge in the skin, TNF-α produced by mast cells has been shown to mediate LN hypertrophy (36). We observed normal LN hypertrophy in TNF-α-deficient mice after HSV-2 infection (data not shown), suggesting that distinct and/or multiple pathways for LN hypertrophy are triggered by viral infection in the vaginal mucosa. We showed that the accumulation of naïve lymphocytes to the local LN is mediated by innate signals alone in the absence of antigenic stimulation. TLR agonists either can directly bind to the vascular endothelial cells and induce remodeling or may activate DCs, which in turn will activate the feed arteriole. TLR stimulation by PAMPs represents a key, but not exclusive, innate signal that induces naïve lymphocyte accumulation. In the case of HSV-2 infection, MyD88-/- mice underwent similar LN enlargement compared with WT mice (data not shown), suggesting that multiple pathways (TLR-dependent and -independent) contribute to mediating this process after live viral infection. This finding is consistent with our previous observation that MyD88-dependent pathways critically control Th1 differentiation but not T cell migration into the dLNs (7).

After natural infection or immunization, our data suggest that the 6–7 days required for the generation of observable Th1 immunity in the local LNs reflect the time required for the rare lymphocytes to be screened for its specificity to microbial antigens. The present findings show that this screening process is augmented by the increase in the recruitment of naïve lymphocytes specifically to the dLN via remodeling of its arterioles, and not simply due to loss of vascular tone. These results demonstrate that remodeling of the feed arteriole occurs with LN hypertrophy, revealing an important link between the microvascular and immune systems. Moreover, enlargement of the feed arteriole is associated with an impaired NO production by endothelium while smooth muscle function is preserved. This loss of NOS function is particularly intriguing, given the known role of the endothelial NO in maintaining homeostatic vasodilation. Thus, this change in endothelial function likely reflects a unique stage in vascular remodeling. Furthermore, increase in LN cellularity was accompanied by the increase in the HEV within the dLNs (Fig. 7). Although the details of the sequence of events leading to this rapid remodeling of both the arterioles and HEV remain to be elucidated, our study demonstrates a key control of microcirculation by the innate immune system. Thus, our data provide evidence that the innate immune system not only enhances the generation of adaptive immune responses through the activation of DCs and lymphocytes, but also through increasing the efficiency of screening for cognate lymphocytes within the dLN by enlarging the primary arteriole feeding the dLN.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. J. Pober and W. Sessa for insightful discussions. K.A.S. was supported by the National Institutes of Health Minority Supplement CA16885S1, and A.S. was supported by a James Hudson Brown–Alexander Brown Coxe postdoctoral fellowship. A.I. is a recipient of the Wyeth–Lederle Vaccine Young Investigator Award and a grant from the Ethel F. Donaghue Women's Health Investigator Program at Yale University, and is a Burroughs Wellcome Investigator in Pathogenesis of Infectious Diseases. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AI054359 (to A.I.), AI062428 (to A.I.), and R21 AG19347 (to S.S.S.).

Author contributions: K.A.S., G.W.P., R.M., S.S.S., and A.I. designed research; K.A.S., G.W.P., A.S., and A.I. performed research; K.A.S., G.W.P., A.S., and A.I. analyzed data; and G.W.P., S.S.S., and A.I. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: ACh, acetylcholine; APC, antigen-presenting cells; CFSE, carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimdyl ester; DC, dendritic cell; dLN, draining lymph node; HEV, high endothelial venule; IFA, incomplete Freund's adjuvant; ivag, intravaginal(ly); LN, lymph node; ndLN, nondraining LN; NOS, NO synthase; PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular pattern; p.i., postinfection; SNP, sodium nitroprusside; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

References

- 1.Banchereau, J. & Steinman, R. M. (1998) Nature 392, 245-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwasaki, A. & Medzhitov, R. (2004) Nat. Immunol. 5, 987-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Itano, A. A. & Jenkins, M. K. (2003) Nat. Immunol. 4, 733-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jankovic, D., Kullberg, M. C., Hieny, S., Caspar, P., Collazo, C. M. & Sher, A. (2002) Immunity 16, 429-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muraille, E., De Trez, C., Brait, M., De Baetselier, P., Leo, O. & Carlier, Y. (2003) J. Immunol. 170, 4237-4241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schnare, M., Barton, G. M., Holt, A. C., Takeda, K., Akira, S. & Medzhitov, R. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2, 947-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato, A. & Iwasaki, A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 16274-16279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasare, C. & Medzhitov, R. (2003) Science 299, 1033-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bousso, P. & Robey, E. (2003) Nat. Immunol. 4, 579-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller, M. J., Wei, S. H., Parker, I. & Cahalan, M. D. (2002) Science 296, 1869-1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoll, S., Delon, J., Brotz, T. M. & Germain, R. N. (2002) Science 296, 1873-1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mempel, T. R., Henrickson, S. E. & Von Andrian, U. H. (2004) Nature 427, 154-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones, C. A., Taylor, T. J. & Knipe, D. M. (2000) Virology 278, 137-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao, X., Deak, E., Soderberg, K., Linehan, M., Spezzano, D., Zhu, J., Knipe, D. M. & Iwasaki, A. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 197, 153-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemmi, H., Takeuchi, O., Kawai, T., Kaisho, T., Sato, S., Sanjo, H., Matsumoto, M., Hoshino, K., Wagner, H., Takeda, K. & Akira, S. (2000) Nature 408, 740-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeuchi, O., Hoshino, K., Kawai, T., Sanjo, H., Takada, H., Ogawa, T., Takeda, K. & Akira, S. (1999) Immunity 11, 443-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Andrian, U. H. (1996) Microcirculation 3, 287-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Payne, G. W., Madri, J. A., Sessa, W. C. & Segal, S. S. (2004) FASEB J. 18, 280-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaech, S. M., Wherry, E. J. & Ahmed, R. (2002) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 251-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milligan, G. N. & Bernstein, D. I. (1995) Virology 212, 481-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parr, M. B., Kepple, L., McDermott, M. R., Drew, M. D., Bozzola, J. J. & Parr, E. L. (1994) Lab. Invest. 70, 369-380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ottaway, C. A. & Parrott, D. M. (1979) J. Exp. Med. 150, 218-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cose, S. C., Jones, C. M., Wallace, M. E., Heath, W. R. & Carbone, F. R. (1997) Eur. J. Immunol. 27, 2310-2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mackay, C. R., Marston, W. & Dudler, L. (1992) Eur. J. Immunol. 22, 2205-2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palframan, R. T., Jung, S., Cheng, G., Weninger, W., Luo, Y., Dorf, M., Littman, D. R., Rollins, B. J., Zweerink, H., Rot, A. & von Andrian, U. H. (2001) J. Exp. Med. 194, 1361-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell, D. J., Kim, C. H. & Butcher, E. C. (2003) Immunol. Rev. 195, 58-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Andrian, U. H. & Mempel, T. R. (2003) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 867-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herman, P. G., Yamamoto, I. & Mellins, H. Z. (1972) J. Exp. Med. 136, 697-714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Csanaky, G., Kalasz, V. & Pap, T. (1991) Acta Morphol. Hung. 39, 251-257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hay, J. B. & Hobbs, B. B. (1977) J. Exp. Med. 145, 31-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gretz, J. E., Anderson, A. O. & Shaw, S. (1997) Immunol. Rev. 156, 11-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matloubian, M., Lo, C. G., Cinamon, G., Lesneski, M. J., Xu, Y., Brinkmann, V., Allende, M. L., Proia, R. L. & Cyster, J. G. (2004) Nature 427, 355-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cahill, R. N., Frost, H. & Trnka, Z. (1976) J. Exp. Med. 143, 870-888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gretz, J. E., Norbury, C. C., Anderson, A. O., Proudfoot, A. E. & Shaw, S. (2000) J. Exp. Med. 192, 1425-1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Itano, A. A., McSorley, S. J., Reinhardt, R. L., Ehst, B. D., Ingulli, E., Rudensky, A. Y. & Jenkins, M. K. (2003) Immunity 19, 47-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLachlan, J. B., Hart, J. P., Pizzo, S. V., Shelburne, C. P., Staats, H. F., Gunn, M. D. & Abraham, S. N. (2003) Nat. Immunol. 4, 1199-1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.