Abstract

Haemophilus ducreyi is the causative agent of chancroid, a sexually transmitted ulcerative disease. In the present study, the Neisseria gonorrhoeae lgtA lipooligosaccharide glycosyltransferase gene was used to identify a homologue in the genome of H. ducreyi. The putative H. ducreyi glycosyltransferase gene (designated lgtA) was cloned and insertionally inactivated, and an isogenic mutant was constructed. Structural studies demonstrated that the lipooligosaccharide isolated from the mutant strain lacked N-acetylglucosamine and distal sugars found in the lipooligosaccharide produced by the parental strain. The isogenic mutant was transformed with a recombinant plasmid containing the putative glycosyltransferase gene. This strain produced the lipooligosaccharide glycoforms produced by the parental strain, confirming that the lgtA gene encodes the N-acetylglucosamine glycosyltransferase.

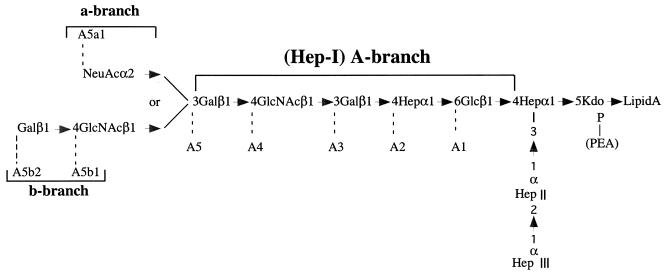

Haemophilus ducreyi is a fastidious gram-negative bacterium that causes the sexually transmitted disease, chancroid. The structure of the H. ducreyi strain 35000HP lipooligosaccharide (LOS) has been characterized in detail and is shown in Fig. 1. The nomenclature for the individual glycoforms and the branches of the LOS chain has been determined (4). The most complex glycoform of the A-branch, designated A5, contains a nonreducing terminal Galβ1-4GlcNAc. Approximately 30% of the terminal galactose residues in the A5 glycoform are substituted with sialic acid to form the a-branch glycoform designated A5a1. Small quantities of the A5 glycoform are substituted with GlcNAc to form the b-branch glycoform designated A5b1 or with Galβ1-4GlcNAc to form the b-branch glycoform designated A5b2 (Fig. 1). The sialyltransferase, both galactosyltransferases, the d-glycero-d-manno-heptose heptosyltransferase, and the glucosyltransferase have previously been identified and isogenic mutants constructed (4, 7, 9, 21, 22). The only unidentified glycosyltransferase necessary for synthesis of the A-branch of the LOS was the N-acetylglucosamine glycosyltransferase.

FIG. 1.

Structure of the LOS of H. ducreyi 35000HP. The nomenclature for the A, a, and b branches, as well as each glycoform has been previously reported (4).

We report here the characterization of the LOS glycoforms produced by an lgtA mutant of H. ducreyi, as well as the glycoforms produced when the mutation is complemented. The results indicate that the lgtA gene in H. ducreyi encodes the N-acetylglucosamine glycosyltransferase. In addition, the relative concentrations of the complex b-branch glycoforms are increased in the complemented strain, suggesting that the LgtA glycosyltransferase might also be the N-acetylglucosamine glycosyltransferase required for synthesis of the b-branch glycoforms.

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

H. ducreyi strains were grown at 35°C with 5% CO2 on chocolate agar (Becton Dickinson). Chocolate agar plates supplemented with streptomycin at 20 μg/ml, kanamycin at 20 μg/ml, and/or X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) at 40 μg/ml were prepared as previously described (9, 17). Brain heart infusion broth supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum, 0.0025% hemin chloride solution (Sigma; predissolved in 20 mM NaOH), and 1% IsoVitaleX (sBHI) was used for growth of H. ducreyi in liquid medium. Escherichia coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) plates or in LB broth supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. Kanamycin or streptomycin was used at 20 μg/ml and ampicillin was used at 50 μg/ml where appropriate. The bacterial strains and plasmids used in the present study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | Host strain used for cloning | Gibco-BRL |

| DH5αpcnB | pcnB, zad::Tn10 | G. Barcak (19) |

| H. ducreyi | ||

| 35000HP | Virulent wild-type strain, isolate from Winnipeg, human passaged | 1 |

| 35000HP-RSM210 | lgtB (galactosyltransferase II) mutant of strain 35000HP | 21 |

| 35000HP-RSM212 | LOS mutant derived from 35000HP by insertion of the ΩKm2 cassette into the N-acetylglucosamine glycosyltransferase gene (lgtA) | This study |

| 35000.4 | lbgA (galactosyltransferase I) mutant of strain 35000 | 20, 22 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pLS88 | Shuttle vector capable of replication in H. ducreyi and E. coli; Kanr Smr Sulr | 6 |

| pWKS30 | Low-copy-number plasmid vector | 25 |

| pCRBlunt II-TOPO | TA-cloning vector; Kanr | Invitrogen |

| pJRS102.0 | Source of the ΩKm2 cassette | 18 |

| pRSM2072 | Suicide vector for selection of H. ducreyi mutants | 3 |

| pRSM2377 | pRSM2072 with BamHI restriction site deleted | This study |

| pRSM2378 | PCRBlunt II-TOPO + 1.9-kb genomic DNA fragment containing the H. ducreyi lgtA gene | This study |

| pRSM2379 | pRSM2377 + 1.9-kb EcoRI fragment from pRSM2378 | This study |

| pRSM2380 | pRSM2379 with ΩKm2 insertion in the putative lgtA gene | This study |

| pRSM2391 | pLS88 + 1.9-kb EcoRI fragment from pRSM2378 | This study |

Kanr, kanamycin resistant; Smr, streptomycin resistant; Sulr, sulfonamide resistant.

Identification of the putative N-acetylglucosamine glycosyltransferase gene.

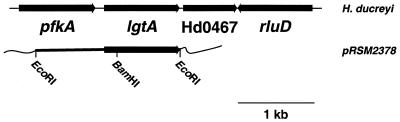

Both Neisseria gonorrhoeae and H. ducreyi infect human genital epithelium and have similar LOS oligosaccharide structures that include a Gal-GlcNAc (N-acetyllactosamine) disaccharide. The N-acetyllactosamine disaccharide is recognized by MAb 3F11. The LgtB glycosyltransferase in N. gonorrhoeae and its counterpart in H. ducreyi are responsible for transferring galactose to the reducing terminal GlcNAc (21). The lgtA gene encoding the N-acetylglucosamine glycosyltransferase is adjacent to the lgtB gene in N. gonorrhoeae. In contrast, the gene encoding the H. ducreyi N-acetylglucosamine glycosyltransferase is not adjacent to the H. ducreyi lgtB gene. We searched the unfinished H. ducreyi genome sequence with the tblastn program to identify genes with homology to N. gonorrhoeae LgtA. A previously unidentified putative glycosyltransferase gene was identified and designated lgtA. The sequence surrounding the putative N-acetylglucosamine glycosyltransferase gene was further characterized. Upstream of lgtA in H. ducreyi is the homologue of the 6-phosphofructose kinase gene, pfkA (Fig. 2). The first open reading frame downstream of lgtA, designated Hd0467, has homology with a hypothetical protein in H. influenzae Rd, Hi1626. Downstream of Hd0467 is the H. ducreyi pseudouridine synthase, designated rluD.

FIG. 2.

Structure of the lgtA region of the strain 35000HP genome and the cloned amplicon containing the lgtA gene (pRSM2378). A DNA fragment containing the lgtA gene was amplified by PCR and cloned into the PCRBlunt II-TOPO vector. The unique BamHI site was used for insertional inactivation of the lgtA gene.

The predicted amino acid sequence of the lgtA gene of H. ducreyi is 42% identical to the derived amino acid sequences of the lgtA homologues in N. gonorrhoeae (11) (GenBank accession number U14554.1), N. meningitidis (14) (GenBank accession number U25839.1), and N. subflava (2) (GenBank accession number AF240672.1). Based on the analysis of mutant glycoforms and direct enzymatic assay, the N. meningitidis lgtA gene has been shown to encode a UDP-GlcNAc transferase (24). Based on the analysis of mutant glycoforms, the LgtA glycosyltransferase from N. gonorrhoeae is also thought to be a UDP-GlcNAc transferase (11). The H. ducreyi LgtA glycosyltransferase also has homology to the LgtD (UDP-GalNAc) glycosyltransferases of N. gonorrhoeae (11) (GenBank accession number U14554.1) and H. influenzae HI1578 (8, 13) (GenBank accession number H64130), as well as a putative glycosyltransferase of Pasteurella multocida (15) (GenBank accession number NP_246077). The homology data strongly suggest that the H. ducreyi lgtA gene encodes a glycosyltransferase.

Cloning of the H. ducreyi lgtA gene and construction of an lgtA mutant.

The H. ducreyi lgtA gene was amplified by PCR using the FailSafe PCR preMix selection kit (Epicenter Technologies). The pair of oligonucleotide primers were targeted to a 1.9-kb DNA fragment containing the lgtA gene and the majority of the pfkA gene (Fig. 2). The two oligonucleotide primers were GlcNAc-F (5′-CTCGGAAATTATTAACCGTGGTGGTAC-3′) and GlcNAc-R (5′-GAGCGGTTATTAATGTTAAATAACAGACGG-3′).

The amplified 1.9-kb DNA product was cloned into PCRBlunt II-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, La.). To lower the plasmid copy number, we transformed into the E. coli DH5αpcnB strain instead of the host strain supplied in the kit. One plasmid with an insert of the correct size was sequenced in both directions by using an ABI 377 DNA automated sequencer and dye terminator chemistries. Contig assembly and sequence analysis were performed with DNASTAR (Madison, Wis.) software. The insert had the correct sequence and the plasmid was designated pRSM2378.

An isogenic mutant was constructed in strain 35000HP by using the strategy of Bozue et al. (3). The insert in pRSM2378 has a unique BamHI site in the lgtA gene that was used to insertionally inactivate the gene (Fig. 2). First, the BamHI site from the suicide vector, pRSM 2072, was removed by digestion with BamHI, blunt ended with Klenow enzyme, religated, and transformed into DH5α. The modified plasmid was designated pRSM2377. The 1.9-kb EcoRI fragment from pRSM2378 was ligated to EcoRI and calf intestine alkaline phosphatase-treated pRSM2377 and then transformed into DH5αpcnB. The resulting plasmid was saved as pRSM2379. To inactivate the lgtA gene in the plasmid, pRSM2379 plasmid DNA was digested with BamHI and blunt ended with Klenow enzyme, and the purified linear plasmid DNA was ligated to the ΩKm2 element, which had been isolated as a SmaI fragment from pJRS102.0. The ligation mixture was transformed into DH5αpcnB, and clones were isolated on LB agar plates supplemented with kanamycin and ampicillin. A plasmid with the appropriate restriction map was saved as pRSM2380. To construct an isogenic lgtA mutant of H. ducreyi 35000HP, pRSM2380 DNA was electroporated into H. ducreyi 35000HP, and kanamycin-resistant clones were selected and then streaked for isolation on chocolate agar containing both kanamycin and X-Gal. Since the hydrolysis product of X-Gal is toxic to H. ducreyi, white clones that grew normally were presumptive mutants which had resolved the cointegrate and therefore were β-galactosidase deficient. Southern blotting was performed on the genomic DNA from several presumptive mutants to verify the allele exchange as well as the loss of plasmid sequences. One mutant, designated 35000HP-RSM212, was saved for further analysis. Growth curves of the mutant and parent strain were similar and the outer membrane protein profiles of the lgtA mutant and the parent strain were indistinguishable (data not shown).

Analysis of the LOS from the isogenic lgtA mutant of H. ducreyi.

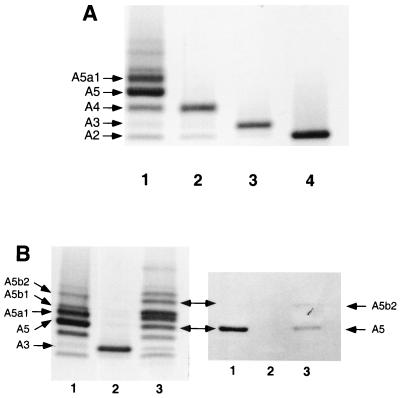

Crude LOS preparations from H. ducreyi wild-type 35000HP and mutant strains were prepared by a modified microphenol method (5), analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 14% acrylamide gel, and silver stained as previously reported (5). The most complex glycoform produced by the H. ducreyi galactosyltransferase II (lgtB) mutant is the A4 glycoform (21) (Fig. 3A, lane 2; see Fig. 1 for corresponding structure), and the most complex glycoform produced by the galactosyltransferase I (lbgA) mutant is the A2 glycoform (22) (Fig. 3A, lane 4; see Fig. 1 for corresponding structure). The most complex LOS glycoform produced by strain 35000HP-RSM212, the lgtA mutant (Fig. 3A, lane 3), ran with a mobility between the LOS glycoforms produced by the mutants deficient in the LgtB and LgbA glycosyltransferases. This result demonstrates that the lgtA gene likely encodes the N-acetylglucosamine glycosyltransferase.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of LOS preparations. (A) LOS preparations from 35000HP (lane 1), the lgtB mutant (lane 2), the lgtA mutant (lane 3), and the lbgA mutant (lane 4) were prepared by the microphenol technique, separated by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by silver staining. The corresponding structure for each glycoform is shown in Fig. 1. (B) Silver-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel and the corresponding Western blot. The gel contains LOS preparations from H. ducreyi 35000HP (lane 1), 35000HP-RSM212, the lgtA mutant (lane 2), and the complemented mutant, 35000HP-RSM212/pRSM2391 (lane 3). The blot, containing the same preparations, was probed with MAb 3F11. Glycoform A5 and glycoform A5b2 react with MAb 3F11. The A5b2 glycoform in the LOS preparation from strain 35000HP was too low in concentration to be observed in this blot.

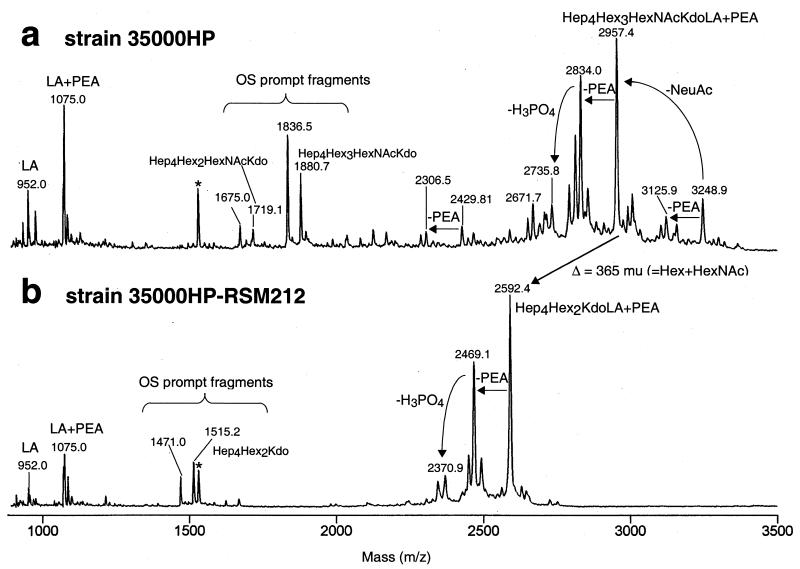

MS analysis of H. ducreyi LOS preparations from strain 35000HP and strain 35000HP-RSM212, the lgtA mutant.

LOS structures from H. ducreyi strain 35000HP and the N-acetylglucosamine glycosyltransferase mutant strain 35000HP-RSM212 were analyzed by mass spectrometry (MS). In each case, ca. 0.5 mg of LOS was treated with mild hydrazine for 30 min at 37°C (12) for conversion into the corresponding water-soluble O-deacylated LOS that is more amenable to MS analysis (10). O-deacylated samples were taken up in water and purified and/or desalted by drop dialysis with a 0.025-mm (pore-size) nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). The dialyzed sample was mixed in a 1:1 ratio with 320 mM 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid solution in acetone, desalted with cation-exchange resin beads (Dowex 50X; NH4+) (16), and then air dried on a stainless steel target. Samples were analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization MS (MALDI-MS) by using a PE Biosystems (Framingham, Mass.) Voyager DE time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer operated with a nitrogen laser (337 nm) in the negative-ion mode under delayed extraction conditions (23). The delay time was 175 ns, and the grid voltage was 93.5% of full acceleration voltage (20 to 30 kV). Spectra were acquired and averaged, and the mass was calibrated with an external calibrant consisting of an equimolar mixture of angiotensin II, bradykinin, LHRH, bombesin, α-MSH (CZE mixture; Bio-Rad) and ACTH 1-24 (Sigma). MALDI spectra of the O-deacylated LOS preparations from the two strains are shown in Fig. 4. In both spectra, one major singly deprotonated molecular ion peak (at m/z 2,957.4 and m/z 2,592.4, respectively) corresponding to the major intact LOS glycoforms was observed. A minor peak observed at m/z 3,248.9 in the preparation from the wild-type strain corresponds to the sialic acid-containing glycoform (Δ=291 mu). The loss of a phosphoethanolamine (PEA) group was observed for all glycoforms yielding peaks at 3,125.9, m/z 2,834.0, and m/z 2,306.5 in the case of the wild-type strain glycoforms and m/z 2,469.1 in the case of the mutant strain glycoforms.

FIG. 4.

Linear negative-ion MALDI-TOF spectra of the O-deacylated LOS preparations from strains 35000HP (a) and 35000HP-RSM212 (b). The observed molecular ions for the individual LOS species appear as unresolved clusters whose centroids correspond to the average mass. The peaks at m/z 1,532.2 that are labeled with an asterisk were found to be artifacts. All Kdo residues were replaced with phosphorylphosphoethanolamine.

Under linear TOF conditions, the molecular ions for the individual LOS species typically appear as unresolved isotopes whose centroids correspond to the average mass. Two of the smaller peaks with a lower mass than the intact LOS are due to “prompt fragmentation” such as the loss of H3PO4 (m/z 2,735.8 and m/z 2,370.9). Further fragmentation resulted in the peaks corresponding to the free lipid A (m/z 952.0), lipid A + PEA (m/z 1,075.0), the free oligosaccharides (m/z 1,880.7, m/z 1,719.1, and m/z 1,515.2, respectively), as well as peaks resulting from the instant loss of CO2 from a Kdo residue of the free OS (m/z 1,836.5, m/z 1,675.0, and m/z 1,471.0, respectively). These data and the corresponding proposed composition of the glycoforms are summarized in Table 2. The most complex glycoform produced by the mutant lacks N-acetylglucosamine, the result anticipated if the lgtA gene encodes the N-acetylglucosamine glycosyltransferase.

TABLE 2.

Theoretical and observed mass data and proposed compositions

| Strain | Mass observed (m/z) | Mass theoretical (m/z) | Proposed compositiona |

|---|---|---|---|

| 35000HP | 3,248.9 | 3,247.8 | NeuAcHep4Hex3HexNAc Kdo(PPEA) LA + PEA |

| 3,125.9 | 3,124.8 | NeuAcHep4Hex3HexNAc Kdo(PPEA) LA | |

| 2,957.4 | 2,956.5 | Hep4Hex3HexNAc Kdo(PPEA) LA + PEA | |

| 2,834.0 | 2,833.5 | Hep4Hex3HexNAc Kdo(PPEA) LA | |

| 2,671.7 | 2,671.4 | Hep4Hex2HexNAc Kdo(PPEA) LA | |

| 2,429.8 | 2,429.0 | Hep4Hex2 Kdo(PPEA) LA + PEA | |

| 2,306.5 | 2,306.0 | Hep4Hex1 Kdo(PPEA) LA | |

| 1,880.7 | 1,880.5 | Hep4Hex3HexNAc Kdo(PPEA)b | |

| 35000HP-RSM212 | 2,592.4 | 2,591.2 | Hep4Hex2 Kdo(PPEA) LA + PEA |

| 2,469.1 | 2,468.2 | Hep4Hex2 Kdo(PPEA) LA | |

| 1,515.2 | 1,515.2 | Hep4Hex2 Kdo(PPEA)b |

LA, diphosphoryl-O-deacylated lipid A; Kdo (PPEA), 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid replaced with phosphorylphosphoethanolamine.

Oligosaccharide prompt fragment.

Complementation of the lgtA mutation in strain 35000HP-RSM212.

The lgtA gene was cloned into the EcoRI site of the shuttle vector pLS88 and transformed into strain 35000HP-RSM212. Expression of the LOS glycoforms produced by this strain were examined by using silver-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel and Western blot analyses. Western blot analysis conditions with murine monoclonal antibody (MAb) 3F11 were similar to the colony blot assay as described previously (9) with the following modification. Briefly, samples separated on a polyacrylamide gel were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane filter by using a Bio-Rad Western blot apparatus at 100 V for 2 h. Blots were then blocked in 2% gelatin (dissolved in buffer A [10 mM Tris-HCl, 1.5 M NaCl; pH 7.4]) for 2 h and incubated overnight with 3F11 MAb diluted 1:1,000 in 1% gelatin. After being washed with buffer A, the filter was incubated with a sheep anti-mouse immunoglobulin G-alkaline phosphatase conjugate. Color development was carried out in BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate) and nitroblue tetrazolium in AP buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2; pH 9.5). It is known that H. ducreyi can add either neuraminic acid or a N-acetyllactosamine to the terminal N-acetyllactosamine structure on the LOS core (Fig. 1), but the predominant LOS glycoform produced by the wild-type strain is A5 (Fig. 3). Interestingly, overexpression of the wild-type lgtA gene on the multicopy plasmid pLS88 dramatically changed the LOS expression pattern, as shown in the silver-stained SDS-PAGE gel (Fig. 3B, left). The A5a1 and A5b1 glycoforms are more abundant than the A5 glycoform in the LOS from the complemented mutant (compare lanes 1 and 3 in Fig. 3B [left]). Additionally, the quantity of the A3 glycoform is decreased relative to that produced by the parental strain. It is possible that the addition of GlcNAc residue in the LOS core is the rate-limiting biosynthetic step and, as a consequence, overexpression of the LgtA glycosyltransferase leads to a relative increase in the abundance of the A5 glycoform, which is then efficiently converted to more complex glycoforms. MAb 3F11 only binds to terminal Galβ1-4GlcNAc. The addition of a distal sugar or neuraminic acid moiety blocks this reactivity. As shown in Fig. 3B, right, neither the A5b1 nor A5a1 glycoforms react with MAb 3F11, as shown by Western blot. The A5 and A5b2 glycoforms contain a terminal N-acetyllactosamine disaccharide that reacts with MAb 3F11. The reactivity of the A5b2 glycoform is most readily visualized in the LOS from the complemented strain that contains a higher concentration of the A5b2 glycoform compared to LOS from the parental strain. It is interesting that the A5b1 glycoform is also present at a high concentration in this complemented strain compared to the parental strain. Another unknown glycoform with a slower mobility than the A5b2 glycoform also exists in this strain. The abundance of this glycoform is similar to that of the A5b2 glycoform. A glycoform with this mobility exists in the wild-type strain as well, but with a very low abundance.

The glycosyltransferase responsible for addition of GlcNAc to the A5 glycoform and the glycosyltransferase responsible for the addition of galactose to the A5b1 glycoform remain to be identified. However, in this biosynthetic pathway, GlcNAc is always added to an LOS glycoform containing a nonreducing terminal galactose, and the resulting GlcNAc-Gal linkage is always β1-3. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that the addition of GlcNAc to both the A3 and the A5 glycoforms is catalyzed by the same N-acetylglucosamine glycosyltransferase, the lgtA gene product. Similarly, the addition of galactose to the A4 and A5b1 glycoforms may be catalyzed by the same galactosyltransferase (LgtB).

In summary, we have identified the glycosyltransferase responsible for addition of N-acetylglucosamine to the A-branch of H. ducreyi LOS. Expression of the lgtA gene on the plasmid pLS88 complements the mutation and also results in an increased concentration of the b-branch glycoforms containing additional GlcNAc or GalGlcNAc. This result suggests that LgtA may also be responsible for addition of GlcNAc to the A5 glycoform.

Nucleotide sequence accession number. The sequence for lgtA has been assigned GenBank accession number AF536817.

Acknowledgments

We thank Huachun Zhong for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AI38444 (to R.S.M.) and R01 AI31254 (to B.W.G.) and by Applied Biosystems, Framingham, Mass., which kindly provided instrumentation to B.W.G. DNA sequence was determined by the Core Facility at Children's Research Institute that was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant HD34615.

Editor: B. B. Finlay

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Tawfiq, J. A., A. C. Thornton, B. P. Katz, K. R. Fortney, K. D. Todd, A. F. Hood, and S. M. Spinola. 1998. Standardization of the experimental model of Haemophilus ducreyi infection in human subjects. J. Infect. Dis. 178:1684-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arking, D., Y. Tong, and D. C. Stein. 2001. Analysis of lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis in the Neisseriaceae. J. Bacteriol. 183:934-941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bozue, J. A., L. Tarantino, and R. S. Munson, Jr. 1998. Facile construction of mutations in Haemophilus ducreyi using lacZ as a counterselectable marker. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 164:269-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bozue, J. A., M. V. Tullius, J. Wang, B. W. Gibson, and R. S. Munson, Jr. 1999. Haemophilus ducreyi produces a novel sialyltransferase: identification of the sialyltransferase gene and construction of mutants deficient in the production of the sialic acid-containing glycoform of the lipooligosaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 274:4106-4114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campagnari, A. A., L. M. Wild, G. E. Griffiths, R. J. Karalus, M. A. Wirth, and S. M. Spinola. 1991. Role of lipooligosaccharides in experimental dermal lesions caused by Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect. Immun. 59:2601-2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon, L. G., W. L. Albritton, and P. J. Willson. 1994. An analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of the Haemophilus ducreyi broad-host-range plasmid pLS88. Plasmid 32:228-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filiatrault, M. J., B. W. Gibson, B. Schilling, S. Sun, R. S. Munson, Jr., and A. A. Campagnari. 2000. Construction and characterization of Haemophilus ducreyi lipooligosaccharide (LOS) mutants defective in expression of heptosyltransferase III and β1,4-glucosyltransferase: identification of LOS glycoforms containing lactosamine repeats. Infect. Immun. 68:3352-3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleischmann, R. D., M. D. Adams, O. White, R. A. Clayton, E. F. Kirkness, A. R. Kerlavage, C. J. Bult, J. F. Tomb, B. A. Dougherty, J. M. Merrick, et al. 1995. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science 269:496-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson, B. W., A. A. Campagnari, W. Melaugh, N. J. Phillips, M. A. Apicella, S. Grass, J. Wang, K. L. Palmer, and R. S. Munson, Jr. 1997. Characterization of a transposon Tn916-generated mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi 35000 defective in lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 179:5062-5071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibson, B. W., J. J. Engstrom, C. M. John, W. Hines, and A. M. Falick. 1997. Characterization of bacterial lipooligosaccharides by delayed extraction matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 8:645-658. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotschlich, E. C. 1994. Genetic locus for the biosynthesis of the variable portion of Neisseria gonorrhoeae lipooligosaccharide. J. Exp. Med. 180:2181-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helander, I. M., K. Nummila, I. Kilpelainen, and M. Vaara. 1995. Increased substitution of phosphate groups in lipopolysaccharides and lipid A of polymyxin-resistant mutants of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 392:15-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hood, D. W., A. D. Cox, W. W. Wakarchuk, M. Schur, E. K. Schweda, S. L. Walsh, M. E. Deadman, A. Martin, E. R. Moxon, and J. C. Richards. 2001. Genetic basis for expression of the major globotetraose-containing lipopolysaccharide from H. influenzae strain Rd (RM118). Glycobiology 11:957-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jennings, M. P., D. W. Hood, I. R. Peak, M. Virji, and E. R. Moxon. 1995. Molecular analysis of a locus for the biosynthesis and phase-variable expression of the lacto-N-neotetraose terminal lipopolysaccharide structure in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol. 18:729-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.May, B. J., Q. Zhang, L. L. Li, M. L. Paustian, T. S. Whittam, and V. Kapur. 2001. Complete genomic sequence of Pasteurella multocida, Pm70. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:3460-3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nordhoff, E., A. Ingendoh, R. Cramer, A. Overberg, B. Stahl, M. Karas, F. Hillenkamp, and P. F. Crain. 1992. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry of nucleic acids with wavelengths in the ultraviolet and infrared. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 6:771-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmer, K. L., W. E. Goldman, and R. S. Munson, Jr. 1996. An isogenic haemolysin-deficient mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi lacks the ability to produce cytopathic effects on human foreskin fibroblasts. Mol. Microbiol. 21:13-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perez-Casal, J., M. G. Caparon, and J. R. Scott. 1991. Mry, a trans-acting positive regulator of the M protein gene of Streptococcus pyogenes with similarity to the receptor proteins of two-component regulatory systems. J. Bacteriol. 173:2617-2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierson, V. L., and G. J. Barcak. 1999. Development of E. coli host strains tolerating unstable DNA sequences on ColE1 vectors. Focus 21:18-19 [Online.] http://www.invitrogen.com:80/Content/Focus/211018.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens, M. K., J. Klesney-Tait, S. Lumbley, K. A. Walters, A. M. Joffe, J. D. Radolf, and E. J. Hansen. 1997. Identification of tandem genes involved in lipooligosaccharide expression by Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect. Immun. 65:651-660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun, S., B. Schilling, L. Tarantino, M. V. Tullius, B. W. Gibson, and R. S. Munson, Jr. 2000. Cloning and characterization of the lipooligosaccharide galactosyltransferase II gene of Haemophilus ducreyi. J. Bacteriol. 182:2292-2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tullius, M. V., N. J. Phillips, N. K. Scheffler, N. M. Samuels, R. S. J. Munson, E. J. Hansen, M. Stevens-Riley, A. A. Campagnari, and B. W. Gibson. 2002. The lbgAB gene cluster of Haemophilus ducreyi encodes a β1,4 galactosyltransferase and an α1,6 dd-heptosyltransferase involved in lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis. Infect. Immun. 70:2853-2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vestal, M. L., P. Juhasz, and S. A. Martin. 1995. Delayed extraction matrix-assisted laser desorption time-of flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 9:1044-1050. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakarchuk, W., A. Martin, M. P. Jennings, E. R. Moxon, and J. C. Richards. 1996. Functional relationships of the genetic locus encoding the glycosyltransferase enzymes involved in expression of the lacto-N-neotetraose terminal lipopolysaccharide structure in Neisseria meningitidis. J. Biol. Chem. 271:19166-19173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, R. F., and S. R. Kushner. 1991. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene 100:195-199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]