Standards 2 and 3 of the national service framework for mental health outline the need to improve health care for patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.1 Healthcare workers in primary care are at the forefront of screening and managing these disorders. Assessment tools available to primary healthcare professionals can take a long time to administer and may need to be interpreted by specialists2; this may limit improvements in care. A screening tool was developed, but only to facilitate epidemiological research.3

The SCOFF questionnaire is a brief and memorable tool designed to detect eating disorders and aid treatment (see figure). It showed excellent validity in a clinical population and reliability in a student population.4,5 We assessed the SCOFF questionnaire in primary care.

Participants, methods, and results

We invited sequential women attenders (aged 18-50) at two general practices in southwest London to participate. We gave participants information sheets that described the study. Women who verbally consented to participate were asked the SCOFF questions in a separate room; this took about two minutes. A researcher blind to the woman's score on the SCOFF questionnaire conducted a clinical diagnostic interview lasting 10-15 minutes, based on criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fourth edition). Women identified by the interview as having an eating disorder were invited to discuss this and were offered the contact number for the Eating Disorders Association. The local research and ethics committee approved the study.

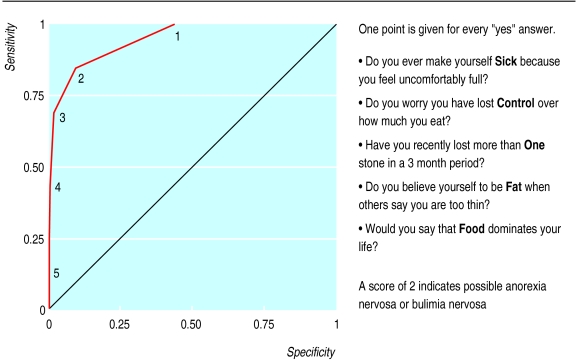

Of the 341 women who agreed to take participate, one (who had a body mass index of 17 (weight (kg)/height (m)2)) had anorexia nervosa, three had bulimia nervosa, and nine had an “eating disorder not otherwise specified.” A receiver operating curve set the optimal threshold for the questionnaire at two or more positive answers to the five questions. With this cut off, the SCOFF questionnaire detected all four cases of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa and seven of nine cases of eating disorders not otherwise specified (figure). The questionnaire had a sensitivity of 84.6% (95% confidence interval 54.6% to 98.1%). In the 328 women confirmed not to have an eating disorder, the questionnaire indicated 34 false positives. It had a specificity of 89.6% (86.3% to 92.9%), positive predictive value of 24.4% (12.9% to 39.5%), and negative predictive value of 99.3% (97.6% to 99.9%).

Comments

The SCOFF questionnaire detected all cases of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. It is an efficient screening tool for eating disorders.

Two missed cases of eating disorders not otherwise specified reflect the reality of clinical situations, in which denial or non-disclosure by patients may occur. One of the patients in whom the diagnosis was missed later disclosed disordered eating behaviour. It may be more difficult and perhaps less pertinent to detect patients who do not meet full criteria for anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa.

The positive predictive value of the questionnaire is low because of the low prevalence of eating disorders in this sample, which was consistent with the Western population as a whole. Overinclusion is acceptable for screening instruments designed for disorders with high mortality rates, particularly as the questionnaire is short and easy to administer. Positive results should be followed by further questioning rather than by automatic referral.

The SCOFF questionnaire is efficient at detecting cases of eating disorders in adult women in primary care. We recommend its use by healthcare professionals in primary care. Future work will assess the validity of the questionnaire in other populations, such as adolescents, in whom the prevalence may be higher.

Figure.

Receiver operating curve showing the effect of cut-off points (1 to 5) for the SCOFF questionnaire to detect cases and non-cases of eating disorders. 1 to 5=minimum number of positive responses to questionnaire

Acknowledgments

Study to be attributed to the Department of Psychiatry at St George's Hospital Medical School, University of London, London. We thank K Kennett for her help with data collection. We also thank Wandle Valley Surgery and Brocklebank Group Practice, particularly T Coffey, who provided study patients. We thank the volunteers for their kind participation.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Department of Health. A national service framework for mental health: modern standards and service models. London: Stationery Office; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garner DM, Olmstead MA, Polivy J. Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Int J Eat Disord. 1983;2:15–34. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beglin SJ, Fairburn CG. Evaluation of a new instrument for the detection of eating disorders in community samples. Psychiatry Res. 1992;44:191–201. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90023-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ. 1999;319:1467–1468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perry L, Morgan J, Reid F, O'Brien A, Brunton J, Luck A, et al. Oral versus written administration of the SCOFF. Int J Eating Disorders (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]