Abstract

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a highly proactive molecule that causes in vivo a systemic inflammatory response syndrome and activates in vitro the inflammatory pathway in different cellular types, including endothelial cells (EC). Because the proinflammatory status could lead to EC injury and apoptosis, the expression of proinflammatory genes must be finely regulated through the induction of protective genes. This study aimed at determining whether an LPS exposure is effective in inducing apoptosis in primary cultures of porcine aortic endothelial cells and in stimulating heat shock protein (Hsp)70 and Hsp32 production as well as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secretion. Cells between third and eighth passage were exposed to 10 μg/mL LPS for 1, 7, 15, and 24 hours (time-course experiments) or to 1, 10, and 100 μg/mL LPS for 7 and 15 hours (dose-response experiments). Apoptosis was not affected by 1 μg/mL LPS but significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner with the highest LPS doses. Furthermore, apoptosis rate increased only till 15 hours of LPS exposure. LPS stimulated VEGF secretion in a dose-dependent manner; its effect became significant after 7 hours and reached a plateau after 15 hours. Both Hsp70 and Hsp32 expressions were induced by LPS in a dose-dependent manner after 7 hours. Subsequent studies were addressed to evaluate the protective role of Hsp32, Hsp70, and VEGF. Hemin, an Hsp32 inducer (5, 20, 50 μM), and recombinant VEGF (100 and 200 ng/mL), were added to the culture 2 hours before LPS (10 μg/mL for 24 hours); to induce Hsp70 expression, cells were heat shocked (42°C for 1 hour) 15 hours before LPS (10 μg/mL for 24 hours). Hemin exposure upregulated Hsp32 expression in a dose-dependent manner and protected cells against LPS-induced apoptosis. Heat shock (HS) stimulated Hsp70 expression but failed to reduce LPS-induced apoptosis; VEGF addition did not protect cells against LPS-induced apoptosis at any dose tested. Nevertheless, when treatments were associated, a reduction of LPS-induced apoptosis was always observed; the reduction was maximal when all the treatments (HS + Hemin + VEGF) were associated. In conclusion, this study demonstrates that LPS is effective in evoking “the heat shock response” with an increase of nonspecific protective molecules (namely Hsp70 and Hsp32) and of VEGF, a specific EC growth factor. The protective role of Hsp32 was also demonstrated. Further investigations are required to clarify the synergic effect of Hsp32, Hsp70, and VEGF, thus elucidating the possible interaction between these molecules.

INTRODUCTION

Endothelial cells (EC) are involved in many pathological conditions as a consequence of their exposition in the vasculature (Cines et al 1998), and increasing evidences indicate that they play a pivotal role in the progression, control, and resolution of the inflammatory response (Keller et al 2003; Valujskikh and Heeger 2003). Exposition to proinflammatory stimuli induces EC activation and promotes vasoconstriction, leukocyte adhesion, coagulation, and thrombosis through the expression of proinflammatory genes. Because this situation could lead to EC injury and apoptosis, the proinflammatory gene expression must be tightly regulated through the induction of protective genes, among which are A20, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL, also known as antiapoptotic molecules (Bach et al 1997). The molecular events regulating the inhibition of apoptosis and the soluble mediators of EC cytoprotection are responsible for the “preconditioned” status, an adaptation condition effective in protecting vasculature against a wide array of insults (Carini and Albano 2003).

In this context, genes other than the well-described antiapototic ones, could exert protective effects. Among these, heat shock proteins (HSPs) have been reported to protect against environmental stressors and are considered as the first response in nonphysiological conditions (Morimoto et al 1994a; Hartl 1996). Members of the HSP70 family act as molecular chaperones, helping new synthesized proteins to be folded and transported across membranes. Members of the HSP70 family are widely distributed in many cellular compartments; some of them are constitutively expressed (Hsc70), whereas others are induced by several stressors (Hsp70) (Li et al 1991; Morimoto et al 1994a; Stege et al 1994). During a stress event, Hsp70s prevent misfolding and promote the proteolytic degradation of damaged proteins, thus acting as surviving factors and apoptosis inhibitors (Buzzard et al 1998).

Also Hsp32, or Hemeoxygenase (HO)-1, the rate-limiting enzyme in the heme catabolism, has been demonstrated to prevent inflammation and EC injury in different models (Otterbein et al 1999, 2003; Otterbein and Choi 2000; Duckers et al 2001; Bulger et al 2003). Therefore, both Hsp70 and Hsp32 exert protective effects and are putative candidates against inflammatory disorders because their induction is independent on the main proinflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor (NF)-κB activation (Stuhlmeier 2000).

Another important molecule involved in the control of inflammatory process is the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). It is well known that VEGF acts as a regulator of physiological and pathological angiogenesis as well as a permeability factor, effective in inducing vascular leakage (Ferrara et al 2003). Apart from these activities, VEGF acts as a survival signal, being effective in inhibiting the apoptosis process induced by a variety of stimuli such as hyperoxia (Alon et al 1995), growth-factor withdrawal, extracellular matrix disruption (Watanabe and Dvorak 1997), and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Munshi et al 2002).

LPS is a highly proactive molecule that causes in vivo a systemic inflammatory response syndrome in which vascular injury is responsible for most of the pathophysiological changes (Gotloib et al 1992; Goddard et al 1996). In vitro, LPS activates the inflammatory pathway in different cellular types, including EC (Bannerman and Goldblum 2003).

On the basis of all these considerations, this study aimed at determining whether a continuous LPS exposure is effective in inducing apoptosis and in stimulating Hsp70 and Hsp32 production and VEGF secretion in primary cultures of porcine aortic endothelial cells (PAEC); another aim was to verify whether these molecules are effective in modulating LPS-induced apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell isolation and culture

Thoracic aortic traits were collected from adult pigs at a local slaughterhouse. After collection, aortas were washed in sterile Dulbecco Phosphate Buffer Solution (DPBS, Cambrex Bio-Science INC, Wakersville, MA, USA), ligated at the ends, and transferred to the laboratory within 1 hour on ice. After ligation of all arterial side branches, aortas were canulated with modified syringe cones and silicone tubes to set up a closed system. The vessels were gently flushed with DPBS to remove residual blood, then they were filled with DPBS added with 0.2% collagenase (Sigma Chemical Company, St Louis, MO, USA) and clamped at both ends. After 20 minutes of incubation at 37°C, the collagenase solution was collected and the vessels were washed with DPBS. The solutions were pooled and centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 minutes. The cellular pellet was resuspended in 1 mL human endothelial basal growth medium (Gibco-Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Gibco-Invitrogen) and 1% antibiotics-antimicotics (Gibco-Invitrogen). Cell number and viability (85–90%) were determined using a Thoma chamber under a phase-contrast microscope after vital staining with trypan blue dye. Approximately 3 × 105 cells was placed in T-25 tissue culture flasks (T25-Falcon, Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 38.5°C. The cells were maintained in a logarithmic growth phase by routine passages every 2–3 days at a 1:3 split ratio.

To confirm their endothelial origin, cultured cells were grown in slide chambers (Falcon, Becton-Dickinson) for 24 hours, they were then fixed with ethanol:acetic acid (2: 1) and stained with 1:200 rabbit polyclonal anti-human factor VIII (Dako A/S, Glostrup, Denmark), 1:100 mouse monoclonal anti-porcine CD31 (Serotec LTD, Oxford, UK), and 1:25 rat monoclonal anti-porcine Caderine (Serotec LTD) antisera. Primary antibodies were added in a humidified chamber for 1 hour at room temperature (RT); fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibodies were then added (1:800 dilution in DPBS). The cells were then counterstained with propidium iodide and examined under an epifluorescence microscope (Eclipse E600 Nikon, Japan) equipped with fluorescein (FITC) and tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC) filters and with a Nikon digital camera.

Cell treatments

Cells between third and eighth passage were grown in a flat-bottom 24-well assay plate (Falcon, Becton-Dickinson) as described above. PAEC were exposed to 10 μg/mL LPS (E. coli 055:B5, Sigma) for 1, 7, 15, and 24 hours (time-course experiments) and to 1, 10, and 100 μg/mL LPS for 7 and 15 hours (dose-response experiments). Hemin, a widely recognized Hsp32 inducer (5, 20, 50 μM, H5533, Sigma), and recombinant VEGF (100 and 200 ng/ mL, V3513, Sigma), were added to the culture 2 hours before LPS (10 μg/mL for 24 hours). To induce Hsp70 expression, cells were heat shocked (42°C for 1 hour) 15 hours before adding LPS (10 μg/mL for 24 hours). Cells and media were then collected and stored until assays.

Cell apoptosis

Vybrant Apoptosis Assay Kits

The Vibrant™ Apoptosis Assay Kit no. 2 (Molecular Probes Europe, Leiden, The Netherlands) combines a fluorescent annexin V conjugate with other indicators of metabolic activity and plasma membrane permeability for the rapid detection of live, apoptotic, and dead cells. According to the manufacturer's instruction, cells were harvested, washed, and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 annexin V. Cells were counterstained with propidium iodide and incubated for 15 minutes at RT; cells were then deposited onto slides and observed under an epifluorescence microscope.

Sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for histone-associated DNA fragment

PAEC were plated (4 × 104/well) in a 24-multiwell plate and were grown to confluence. After each treatment, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Cell Death Detection ElisaPlus 1774425, Roche, Penzberg, Germany), cells were harvested in lysis buffer and the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were separated by centrifugation at 200 × g. Twenty microliters of supernatant (cytoplasmic fraction) was added to a streptavidin-coated microtiter plate. A biotin-labeled antihistone antibody was added, followed by a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated anti-DNA antibody. The photometric analysis of the reaction produced by the peroxidase and substrate permitted the quantification of the nucleosome-bound DNA fragments.

TUNEL Assay

The apoptosis-induced chromatin fragmentation in PAEC was evidenced by using the ApopTag Fluorescein in situ apoptosis detection Kit (S7110-Kit, Intergen Company, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. In brief, after each treatment, cells were fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol, then incubated first with terminal deoxynucleotide transferase enzyme for digoxigenin deoxynucleotide triphosphate (dNTP) incorporation (30 minutes at 37°C), and, after several washings, incubated with antidigoxigenin-fluorescein antibody (30 minutes at RT in the dark). Cells were counterstained with propidium iodide and observed under an epifluorescence microscope.

VEGF determination

VEGF concentrations in culture media of both kinetic and dose-response experiments were determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, Quantikine; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) previously validated for the measurement of porcine VEGF (Mattioli et al 2001; Galeati et al 2003). The sensitivity of the assay was 5 pg/mL, and the intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were less than 6% and 10%, respectively.

Western blot analysis

Cells from dose-response and time-dependence experiments were harvested and lysated in sodium dodecil sulphate (SDS) buffer (Tris-HCl 62.5 mM, pH 6.8; SDS 2%, glicerol 20%). Protein content of cell lysates was determined by a protein assay kit (Sigma). Aliquots containing 10 μg of proteins were separated on NuPage 10% Bis-Tris Gel (Gibco) for 50 minutes at 200 V. Proteins were then electrophoretically transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Blots were washed in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and protein transfer was checked by staining the nitrocellulose membranes with 0.2% Ponceau Red and the gels with Comassie Blue. Nonspecific protein binding on nitrocellulose membranes was blocked with 3% milk powder in PBS–0.1% Tween-20 (T20) for 3 hours at RT. The membranes were then incubated with a 1:1000 dilution of an anti-Hsp70 (SPA 810, Stressgen, Victoria, BC, Canada) monoclonal antibody or with a 1:2000 dilution of an anti-Hsp32 (SPA 896, Stressgen) polyclonal antibody in tris-buffered saline–T20 (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 0.1% T-20) overnight at 4°C. After several washings with PBS-T20, the membranes were incubated with the secondary biotin-conjugate antibody and then with a 1:1000 dilution of an antibiotin HRP-linked antibody. The Western blots were developed using a chemiluminescent substrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for β-tubulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) to normalize the results. The relative protein content was determined by the density of the resultant bands and expressed in arbitrary units relative to the β-tubulin content, using the Quantity One Software (Bio-Rad).

Statistical analysis

Each treatment was replicated 3 or 6 times. Data were analyzed using the one-way analysis of variance by the SPSS program version 8.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. A probability of at least P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Three to five PAEC flasks (T-25) were obtained on average from 15 cm aorta trait. The cells reached confluence (106 cells/flask) in 2–3 days. Virtually almost all the cells were stained positively for the 3 antibodies with a correct immunolocalization (pictures not shown), thus demonstrating to be endothelium derived.

LPS-induced apoptosis in PAEC

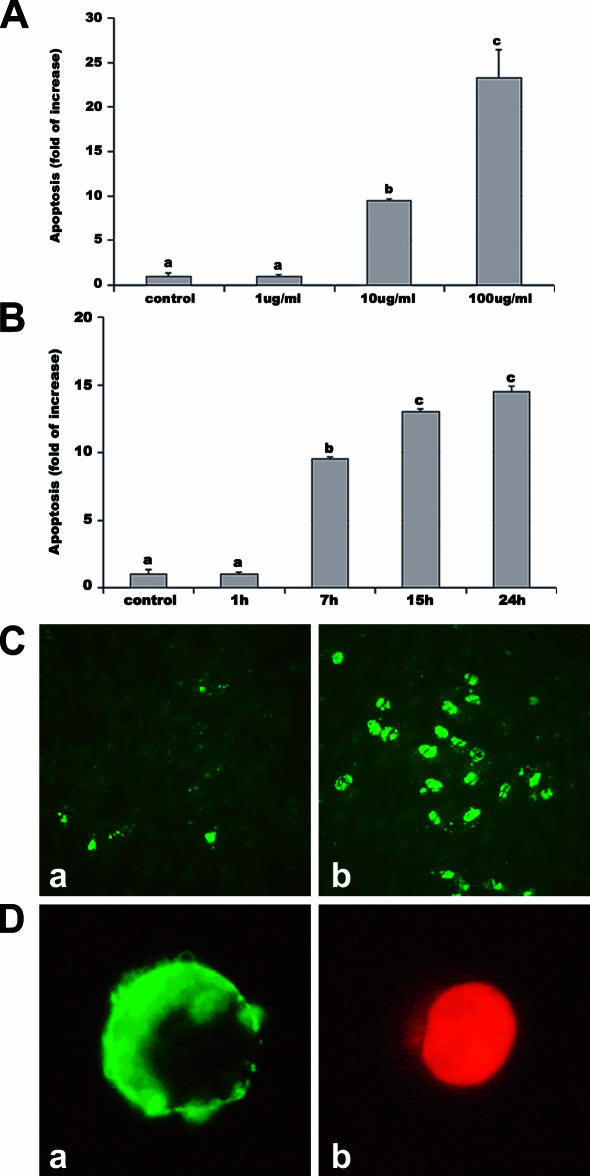

Both dose-response and time-course experiments demonstrated that LPS induces apoptosis in PAEC. The results obtained by the 3 methods used (Fig 1) were coincident and showed that EC death was due to apoptosis, being necrotic cells less than 2% as indicated by both TUNEL and annexin tests (Fig 1C, D). EC apoptosis was not affected by 1 μg/mL LPS but was significantly (P < 0.001) stimulated in a dose-dependent manner by the higher doses (Fig 1A). When exposed to 100 μg/mL LPS for 15 hours, EC showed a massive apoptosis death, so these data were excluded. The time-course experiment showed that the percentage of apoptotic EC increased with time, becoming significantly (P < 0.001) higher than controls after 7 hours (Fig 1B).

Fig 1.

LPS-induced apoptosis in PAEC. Apoptosis was assessed by 3 methods: the sandwich ELISA for histone-associated DNA fragments, the Vybrant Apoptosis Assay Kit, and the TUNEL method. Apoptosis is represented as fold of increase vs control on the basis of ELISA results. Apoptosis after exposure for 7 hours to different LPS doses (A) and after exposure to 10 μg/mL LPS for different periods (B). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 6 replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.001). (C) Representative TUNEL: cells with green fluorescence represent apoptotic cells. (a) control; (b) 24 hours of LPS. (D) Representative Annexin test: membranes of apoptotic cells showed a strong green labeling (a), whereas necrotic cells present both weak membrane Annexin V and strong nuclear propidium staining (b). ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PAEC, porcine aortic endothelial cells

LPS-induced Hsp70 and Hsp32 expression and VEGF secretion

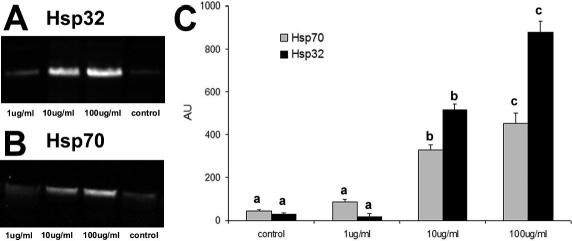

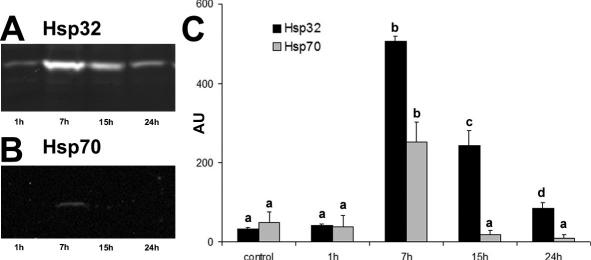

Western blot for Hsp70 and Hsp32 showed a single band of expected molecular weight for both proteins (Figs 2A, B and 3A, B). As shown in Figure 2, in control cells, Hsp70 and Hsp32 were always detected at basal levels. Hsp70 and Hsp32 expression was unaffected by 1 μg/ mL LPS but was stimulated by 10 and 100 μg/mL LPS in a dose-dependent manner after 7 hours (Fig 2C). In the time-course experiments with 10 μg/mL LPS, both Hsp70 and Hsp32 expressions reached the maximum level after 7 hours of LPS exposure; after 15 hours of stimulation, Hsp70 expression returned to basal level, whereas Hsp32 expression decreased more slowly (Fig 3C).

Fig 2.

Hsp32 and Hsp70 expression in PAEC treated with increasing doses (1, 10, 100 μg/mL) of LPS for 7 hours. Representative Western blot of Hsp32 (A), Hsp70 (B), and relative Hsp70 and Hsp32 content (AU, Arbitrary Units) (C). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). Hsp, heat shock protein; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PAEC, porcine aortic endothelial cells

Fig 3.

Hsp32 and Hsp70 expression in PAEC exposed to 10 μg/ mL LPS for different periods (1, 7, 15, and 24 hours). Representative Western blot of Hsp32 (A), Hsp70 (B), and relative Hsp70 and Hsp32 content (AU, Arbitrary Units) (C). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). Hsp, heat shock protein; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PAEC, porcine aortic endothelial cells

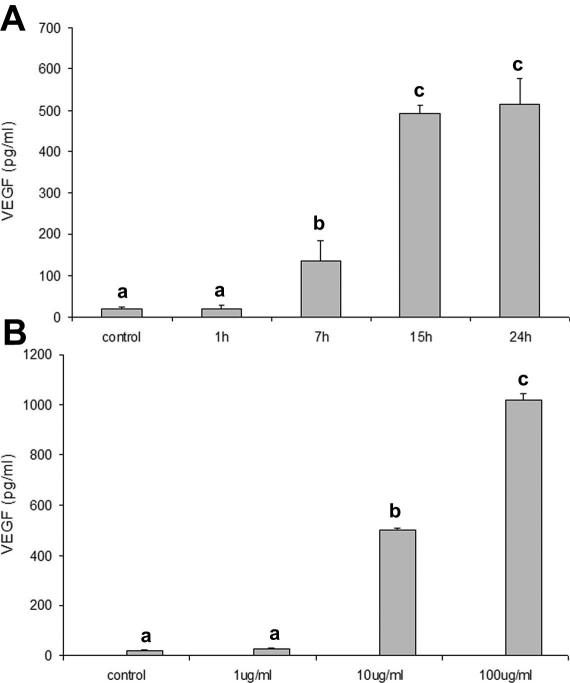

VEGF concentration in culture media of LPS-stimulated cells was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than that in control after 7 hours and reached a plateau after 15 hours (Fig 4A). LPS stimulated VEGF secretion in a dose-dependent manner after 7 hours (Fig 4B).

Fig 4.

Effects of LPS on VEGF secretion by PAEC. (A) Effects of different periods of exposure to 10 μg/mL LPS. (B) Effects of 7 hours exposure to different LPS doses. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PAEC, porcine aortic endothelial cells; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor

LPS-induced apoptosis as modulated by Hsp32, Hsp70, and VEGF

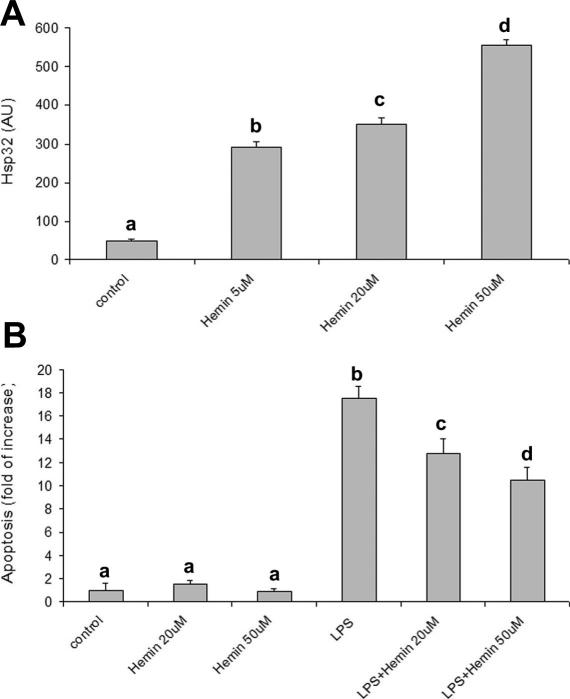

Hemin exposure upregulated Hsp32 expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 5A), with maximum effect at 50 μM. As shown in Figure 5B, hemin (20 and 50 μM) significantly (P < 0.001) reduced LPS-induced apoptosis. Heat shock upregulated Hsp70 expression (Fig 6A) but failed to reduce LPS-induced apoptosis (Fig 6B).

Fig 5.

Effects of hemin on Hsp32 expression and on LPS-induced apoptosis. (A) Hemin (5, 20, or 50 μM) upregulates Hsp32 expression after 15 hours exposure. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). (B) Hemin reduces LPS-induced apoptosis. Apoptosis is represented as fold of increase vs control on the basis of the sandwich ELISA for histone-associated DNA fragments. Hemin (20 or 50 μM) was added to the culture medium 2 hours before LPS exposure (10 μg/mL for 24 hours). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 6 replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.001). ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; Hsp, heat shock protein; LPS, lipopolysaccharide

Fig 6.

Effect of (HS) treatment on Hsp70 expression and LPS-induced apoptosis. (A) Heat shock stimulates Hsp70 expression. The cells were heat shocked (HS = 42°C for 1 hour) and recovered at different times (1, 7, 15, 24 hours). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). (B) Hsp70 stimulation fails to reduce LPS-induced apoptosis. Apoptosis is represented as fold of increase vs control on the basis of the sandwich ELISA for histone-associated DNA fragments. The cells were heat shocked (HS = 42°C for 1 hour) and then cultured in standard conditions for 15 hours before LPS exposure (10 μg/mL for 24 hours). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 6 replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.001). ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HS, heat shock; Hsp, heat shock protein; LPS, lipopolysaccharide

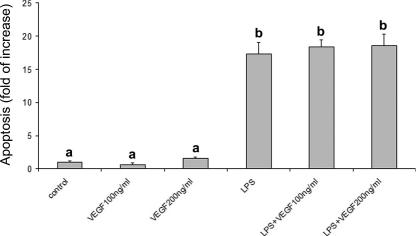

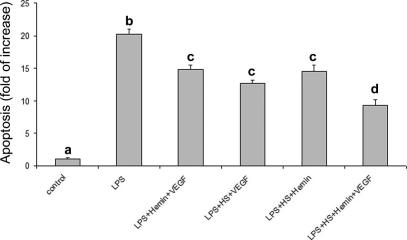

VEGF addition did not protect cells against LPS-induced apoptosis at any dose tested (Fig 7); nevertheless, when treatments were associated, a reduction of LPS-induced apoptosis was always observed (Fig 8). The reduction was maximal when all the treatments (HS + hemin + VEGF) were associated.

Fig 7.

Effect of recombinant VEGF on LPS-induced apoptosis. VEGF fails to reduce LPS-induced apoptosis. Apoptosis is represented as fold of increase vs control on the basis of the sandwich ELISA for histone-associated DNA fragments. Recombinant VEGF (100 or 200 ng/mL) was added to the culture media 2 hours before LPS exposure (10 μg/mL for 24 hours). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 6 replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.001). ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor

Fig 8.

Effect of treatment association on LPS-induced apoptosis. The maximum protective effect was obtained by the association of the 3 treatments (VEGF, hemin, heat shock). Apoptosis is represented as fold of increase vs control on the basis of the sandwich ELISA for histone-associated DNA fragments. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 6 replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.001). ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor

DISCUSSION

EC injury is a common finding in the pathogenesis of several diseases including atherosclerosis (Chen and Keaney 2004), hypertension (Blann 2000), and congestive heart failure (Katz 1997). During bacterial sepsis, EC death is the final step of a process beginning when quiescent ECs are induced to express procoagulant, proadhesive, and vasoconstrictive factors. EC activation has been extensively studied in in vitro models, but this experimental approach needs to be carefully monitored because of the tendency of EC to lose specific functions as culture time increases (Cines et al 1998). For this reason, we set up a protocol of PAEC isolation and culture and we used only cells from the third to the eighth passage.

Results from this study demonstrate that LPS induces apoptosis in primary PAEC culture; these findings are in agreement with those obtained in other species both in vitro (bovine: Frey and Finlay 1998; ovine: Hoyt et al 1995; human: Pohlman and Harlan 1989) and in vivo (murine: Koshi et al 1993; rabbit: McCuskey et al 1996; ovine: Meyrick 1986).

Our data indicate that the increase of apoptosis is time-course dependent till 15 hours, whereas the apoptotic rate increase after this time is not significant, possibly as a consequence of the synthesis of protective molecules. A wide range of nonphysiological conditions, including heat, UV light, ionizing radiation, toxic chemicals, and heavy metals, have been demonstrated to be effective in inducing the well-known “heat shock response” by stimulating cells to synthesize Hsps (Morimoto et al 1994a). Among these, Hsp70 and Hsp32 show cytoprotective effects and are putative candidates against inflammatory disorders because their induction is independent on the main proinflammatory transcription factor NF-κB activation (Stuhlmeier 2000).

LPS ability to induce HSPs expression is contradictory. In an in vivo mouse model, LPS alone failed to induce Hsp70 and Hsp32 expression (Morikawa et al 1998), whereas Fujiwara et al (1999) demonstrated a differential induction of Hsp32 and Hsp70 in rat brain after intraperitoneal LPS injection. Results from this study show an LPS-induced upregulation of both Hsp70 and Hsp32, with Hsp70 less induced than Hsp32. Moreover, LPS failed to induce a continuous protein synthesis, and both Hsp70 and Hsp32 decreased after a peak. We may hypothesize that HSPs increase during the first period of treatment could protect the cells by reducing the amount of factors, as denaturated proteins, effective in activating heat shock genes (Morimoto et al 1994a). A sort of preconditioning mechanism may be hypothesized: HSPs increase during the first hours of LPS exposure could be responsible for the later cellular protection, as recently described in many in vivo models (Rosenzweig et al 2004; Wang et al 2004). Therefore, to verify whether Hsp70 and Hsp32 may be, at least in part, responsible for cellular protection against LPS-induced apoptosis, we induced their expression with specific stimuli (heat shock for Hsp70 and hemin for Hsp32) before challenging cells with LPS. In our model, Hemin strongly upregulated Hsp32 expression and protected cells against LPS-induced apoptosis. These results are in agreement with those of Chen et al (2004), who demonstrated that HO-1 stimulation protects porcine renal epithelial cells against Escherichia coli toxin–mediated apoptosis.

On the contrary, Hsp70 induction failed to reduce apoptosis. These data are conflicting with those of Komarova et al (2004), who evidenced Hsp70 ability to suppress apoptosis through binding the precursors of both caspase-3 and caspase-7. It should be taken into account that LPS has been shown to be effective in stimulating many different caspases, including 3, 6, and 8 (Bannermann and Goldblum 2003), it is likely that, in our model, Hsp70 induction did not counterbalance multiple LPS-induced apoptotic signals. Because of the well-known thermoinducibility of other HSPs such as small HSPs (Morimoto et al 1994b), our results could also suggest that these molecules are not involved in the protection mechanism(s) against LPS-induced apoptosis.

Other molecules, such as VEGF, could possibly contribute to reduce LPS-induced apoptosis, as demonstrated by Munshi et al (2002). For this reason, we determined VEGF secretion and we observed an increase in VEGF production by LPS-stimulated PAEC. These results are in agreement with those obtained by others, reporting a VEGF production by LPS-stimulated macrophages (Itaya et al 2001) and myocites (Sugishita et al 2000). Interestingly, a Hsp32-mediated VEGF upregulation has been reported by Jozkowicz et al (2003); this finding agrees well with our findings showing a different time-course response between VEGF and Hsp32, with Hsp32 expression preceding VEGF secretion. Also, because a VEGF-induced HSP32 expression has been reported in vivo (Bussolati et al 2004), a positive feedback between these 2 molecules may be hypothesized. To test its effective protective role, we added recombinant VEGF to the culture media before LPS exposure, but, quite surprisingly, we did not observe any protective effect. Interestingly, although recombinant VEGF and Hsp70 alone failed to reduce LPS-induced apoptosis, their association exerted a positive effect; nevertheless, further investigation is required to elucidate the possible interaction between these molecules. Finally, multiple treatments always induced a protective effect; in particular, the combination of VEGF, heat shock, and hemin resulted in the maximal LPS-induced apoptosis reduction, thus suggesting that these molecules could act through different pathways with a possible synergic effect.

Taken together, the present data demonstrate that LPS is effective in inducing apoptosis in PAEC and in evoking the heat shock response with an increase of nonspecific protective molecules (namely, Hsp70 and Hsp32) and of a specific EC growth factor, VEGF; the protective role of Hsp32 was also demonstrated. Further investigations are required to clarify the synergic effect of Hsp32, Hsp70, and VEGF by elucidating the possible interaction between these molecules.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Ministero della Salute, D. LGs. 502/1922 art 12 (Regione Veneto/2002) and by MIUR PRIN grants.

REFERENCES

- Alon T, Hemo I, Itin A, Pe'er J, Stone J, Keshet E. Vascular endothelial growth factor acts as a survival factor for newly formed retinal vessels and has implications for retinopathy of prematurity. Nat Med. 1995;1:1024–1028. doi: 10.1038/nm1095-1024.1078-8956(1995)001[1024:VEGFAA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach FH, Hancock WW, Ferran C. Protective genes expressed in endothelial cells: a regulatory response to injury. Immunol Today. 1997;18:483–486. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01129-8.0167-5699(1997)018[0483:PGEIEC]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blann AD. Endothelial cell activation, injury, damage and dysfuction: separate entities or mutual terms? Blood Coag Fibrynolysis. 2000;11:623–630. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200010000-00006.0957-5235(2000)011[0623:ECAIDA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulger EM, Garcia I, Maier RV. Induction of heme-oxygenase 1 inhibits endothelial cell activation by endotoxin and oxidant stress. Surgery. 2003;134:146–152. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.215.0039-6060(2003)134[0146:IOHIEC]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussolati B, Ahmed A, Pemberton H, Landis RC, Di Carlo F, Haskard DO, Mason JC. Bifunctional role for VEGF-induced heme oxygenase-1 in vivo: induction of angiogenesis and inhibition of leukocytic infiltration. Blood. 2004;103:761–766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1974.0006-4971(2004)103[0761:BRFVHO]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzzard KA, Giaccia AJ, Killender M, Anderson RL. Heat shock protein 72 modulates pathways of stress-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17147–17153. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.17147.0021-9258(1998)273[17147:HSPMPO]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carini R, Albano E. Recent insights on the mechanisms of liver pre-conditioning. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1480–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.05.005.0016-5085(2003)125[1480:RIOTMO]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Keaney J. Reactive oxygen species-mediated signal transduction in the endothelium. Endothelium. 2004;11:109–121. doi: 10.1080/10623320490482655.1062-3329(2004)011[0109:ROSSTI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Bao W, Aizman R, Huang P, Aspevall O, Gustafsson LE, Ceccatelli S, Celsi G. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase mediates apoptosis induced by uropathogenic Escherichia coli toxins via nitric oxide synthase: protective role of heme oxygenase-1. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:127–135. doi: 10.1086/421243.0022-1899(2004)190[0127:AOESKM]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cines DB, Pollak ES, and Buck CA. et al. 1998 Endothelial cells in physiology and in the pathophysiology of vascular disorders. Blood. 91:3527–3561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckers HJ, Boehm M, and True AL. et al. 2001 Heme oxygenase-1 protects against vascular constriction and proliferation. Nat Med. 7:693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCourter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669.1078-8956(2003)009[0669:TBOVAI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey EA, Finlay BB. Lipopolysaccharide induces apoptosis in a bovine endothelial cell line via a soluble CD14 dependent pathway. Microb Pathog. 1998;24:101–109. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0178.0882-4010(1998)024[0101:LIAIAB]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T, Takahashi T, Suzuki T, Yamasaki A, Hirakawa M, Akagi R. Differential induction of brain heme oxygenase-1 and heat shock protein 70 mRNA in sepsis. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 1999;105:55–66.1078-0297(1999)105[0055:DIOBHO]2.0.CO;2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeati G, Spinaci M, Govoni N, Zannoni A, Fantinati P, Seren E, Tamanini C. Stimulatory effects of fasting on vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production by growing pig ovarian follicles. Reproduction. 2003;126:647–652.0034-4958(2003)126[0647:SEOFOV]2.0.CO;2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard CM, Allard MF, Hogg JC, Walley KR. Myocardial morphometric changes related to decreased contractility after endotoxin. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H1446–H1452. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.4.H1446.0002-9513(1996)270[H1446:MMCRTD]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotloib L, Shostak A, Galdi P, Jaichenko J, Fudin R. Loss of microvascular negative charges accompanied by interstitial edema in septic rats' heart. Circ Shock. 1992;36:45–56.0092-6213(1992)036[0045:LOMNCA]2.0.CO;2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl FU. Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding. Nature. 1996;381:571–579. doi: 10.1038/381571a0.0028-0836(1996)381[0571:MCICPF]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt DG, Mannix RJ, Rusnak JM, Pitt BR, Lazo JS. Collagen is a survival factor against LPS-induced apoptosis in cultured sheep pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:L171–L177. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.269.2.L171.0002-9513(1995)269[L171:CIASFA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itaya H, Imaizumi T, Yoshida H, Koyama M, Suzuki S, Satoh K. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human monocyte/macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide. Tromb Haemost. 2001;85:171–176.0340-6245(2001)085[0171:EOVEGF]2.0.CO;2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jozkowicz A, Huk I, Nigisch A, Weigel G, Dietrich W, Motterlini R, Dulak J. Heme oxygenase and angiogenic activity of endothelial cells: stimulation by carbon monoxide and inhibition by tin protoporphyrin-IX. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003;5:155–162. doi: 10.1089/152308603764816514.1523-0864(2003)005[0155:HOAAAO]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz SD. Mechanisms and implications of endothelial dysfunction in congestive heart failure. Curr Opin Cardiol. 1997;12:259–264. doi: 10.1097/00001573-199705000-00007.0268-4705(1997)012[0259:MAIOED]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller TT, Mairuhu AT, and de Kruif MD. et al. 2003 Infections and endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res. 60:40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova EY, Afanasyeva EA, Bulatova MM, Cheetham ME, Margulis BA, Guzhova IV. Downstream caspases are novel targets for the antiapoptotic activity of the molecular chaperone hsp70. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2004;9:265–275. doi: 10.1379/CSC-27R1.1.1466-1268(2004)009[0265:DCANTF]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshi R, Mathan VI, David S, Mathan MM. Enteric vascular endothelial response to bacterial endotoxin. Int J Exp Pathol. 1993;74:593–601.0959-9673(1993)074[0593:EVERTB]2.0.CO;2 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GC, Li LG, Liu YK, Mak JY, Chen LL, Lee WM. Thermal response of rat fibroblast stably transfected with the human 70 heat shock protein-encoding gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:1681–1685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1681.0027-8424(1991)088[1681:TRORFS]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattioli M, Barboni B, Turriani M, Galeati G, Zannoni A, Castellani G, Berardinelli P, Scapolo PA. Follicle activation involves vascular endothelial growth factor production and increased blood vessel extension. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:1014–1019. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.4.1014.0006-3363(2001)065[1014:FAIVEG]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCuskey RS, Urbaschek R, Urbaschek B. The microcirculation during endotoxemia. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32:752–763.0008-6363(1996)032[0752:TMDE]2.0.CO;2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyrick BO. Endotoxin-mediated pulmonary endothelial cell injury. Fed Proc. 1986;45:19–24.0014-9446(1986)045[0019:EPECI]2.0.CO;2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa A, Kato Y, Sugiyama T, Koide N, Kawai M, Fukada M, Yoshida T, Yokochi T. Altered expression of constitutive type and inducible type heat shock proteins in response of D-galactosamine-sensitized mice to lipopolysaccharide as an experimental endotoxic shock model. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1998;21:37–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01147.x.0928-8244(1998)021[0037:AEOCTA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto RI, Tissieres A, and Georgopoulos C 1994a Progress and perspectives on the biology of heat shock proteins and molecular chaperones. In: The Biology of Heat Shock Proteins and Molecular Chaperones, ed Morimoto RI, Tissieres A, Georgopoulos C. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, NY, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto RI, Tissieres A, and Georgopoulos C 1994b Expression and function of the low-molecular-weight heat shock proteins. In: The Biology of Heat Shock Proteins and Molecular Chaperones, ed Morimoto RI, Tissieres A, Georgopoulos C. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, NY, 335–373. [Google Scholar]

- Munshi N, Fernandis AZ, Cherla RP, Park IW, Ganju RK. Lipopolysaccharide-induced apoptosis of endothelial cells and its inhibition by vascular endothelial growth factor. J Immunol. 2002;168:5860–5866. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5860.0022-1767(2002)168[5860:LAOECA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein LE, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase: colors of defense against cellular stress. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L1029–L1037. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1029.1040-0605(2000)279[L1029:HOCODA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein LE, Lee PJ, Chin BY, Petrache I, Camhi SL, Alam J, Choi AM. Protective effects of heme oxygenase-1 in acute lung injury. Chest. 1999;116:61S–63S. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.suppl_1.61s-a.0012-3692(1999)116[61S:PEOHOI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein LE, Soares MP, Yamashita K, Bach FH. Heme oxygenase-1 unleasing the protective properties of heme. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:449–455. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00181-9.1471-4906(2003)024[0449:HOUTPP]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlman TH, Harlan JM. Human endothelial cell response to lipopolysaccharide, interleukin-1, and tumor necrosis factor is regulated by protein synthesis. Cell Immunol. 1989;119:41–52. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(89)90222-0.0008-8749(1989)119[0041:HECRTL]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig HL, Lessov NS, Henshall DC, Minami M, Simon RP, Stenzel-Poore MP. Endotoxin preconditioning prevents cellular inflammatory response during ischemic neuroprotection in mice. Stroke. 2004;35:2576–2581. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000143450.04438.ae.0039-2499(2004)035[2576:EPPCIR]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stege GJ, Li GC, Li L, Kampinga HH, Konings AW. On the role of hsp72 in heat-induced intranuclear protein aggregation. Int J Hyperthermia. 1994;10:659–674. doi: 10.3109/02656739409022446.0265-6736(1994)010[0659:OTROHI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuhlmeier KM. Activation and regulation of Hsp32 and Hsp70. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:1161–1167. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01112.x.0014-2956(2000)267[1161:AAROHA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugishita Y, Shimizu T, and Yao A. et al. 2000 Lipopolysaccharide augments expression and secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor in rat ventricular myocites. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 268:657–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valujskikh A, Heeger PS. Emerging roles of endothelial cells in transplant rejection. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:493–498. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00110-9.0952-7915(2003)015[0493:EROECI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Meng X, Tsai B, Wang JF, Turrentine M, Brown JW, Meldrum DR. Preconditioning up-regulates the soluble TNF receptor I response to endotoxin. J Surg Res. 2004;121:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.02.017.0022-4804(2004)121[0020:PUTSTR]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Dvorak HF. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor inhibits anchorage-disruption-induced apoptosis in microvessel endothelial cells by inducing scaffold formation. Exp Cell Res. 1997;233:340–349. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3583.0014-4827(1997)233[0340:VPVEGF]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]