Abstract

During intravascular hemolysis in human disease, vasomotor tone and organ perfusion may be impaired by the increased reactivity of cell-free plasma hemoglobin (Hb) with NO. We experimentally produced acute intravascular hemolysis in a canine model in order to test the hypothesis that low levels of decompartmentalized or cell-free plasma Hb will severely reduce NO bioavailability and produce vasomotor instability. Importantly, in this model the total intravascular Hb level is unchanged; only the compartmentalization of Hb within the erythrocyte membrane is disrupted. Using a full-factorial design, we demonstrate that free water–induced intravascular hemolysis produces dose-dependent systemic vasoconstriction and impairs renal function. We find that these physiologic changes are secondary to the stoichiometric oxidation of endogenous NO by cell-free plasma oxyhemoglobin. In this model, 80 ppm of inhaled NO gas oxidized 85–90% of plasma oxyhemoglobin to methemoglobin, thereby inhibiting endogenous NO scavenging by cell-free Hb. As a result, the vasoconstriction caused by acute hemolysis was attenuated and the responsiveness to systemically infused NO donors was restored. These observations confirm that the acute toxicity of intravascular hemolysis occurs secondarily to the accelerated dioxygenation reaction of plasma oxyhemoglobin with endothelium-derived NO to form bioinactive nitrate. These biochemical and physiological studies demonstrate a major role for the intact erythrocyte in NO homeostasis and provide mechanistic support for the existence of a human syndrome of hemolysis-associated NO dysregulation, which may contribute to the vasculopathy of hereditary, acquired, and iatrogenic hemolytic states.

Introduction

NO is continuously synthesized from endothelium and regulates homeostatic vascular functions such as vasodilation, inhibition of platelet activation and thrombosis, inhibition of endothelial adhesion molecule and endothelin-1 expression, and modulation of intimal and smooth muscle proliferation (1–5). A paradox and controversy in vascular biology surrounds the near diffusion-limited dioxygenation reaction of NO with oxyhemoglobin that oxidizes NO to nitrate, an inactive metabolite (Reaction 1).

Reaction 1

| 1 |

where HbFeII-O2 is ferrous oxyhemoglobin and HbFeIII is methemoglobin.

The rapid (107 M–1 s–1) and irreversible nature of this reaction in the context of an extremely high concentration of intravascular oxyheme groups (10,000 μM) suggests that endothelium-derived NO should be incapable of autocrine diffusion to smooth muscle secondary to rapid inactivation (6–9). Indeed, even hemoglobin (Hb; at 6 μM oxyheme) in buffer completely inhibits endothelium-dependent blood flow in aortic ring bioassays and produces vasoconstriction in vivo (10). It is believed that the compartmentalization of Hb within the erythrocyte limits this inactivation reaction. In vitro studies suggest that combined NO diffusional barriers along the endothelium in laminar flowing blood (11–13), in the unstirred layer around the erythrocyte (14, 15), and in the submembrane protein scaffolding of the erythrocyte (16, 17) reduce the reaction rate of NO with intracellular Hb by 100- to 1,000-fold. In addition to the formation of diffusional barriers, the erythrocyte limits Hb extravasation into the extracellular space (10).

While a physiological role for the erythrocyte in modulating the NO-Hb reaction is supported by the observed vasoconstrictive effects and systemic toxicity of cell-free, Hb–based blood substitutes (6, 7), and is consistent with the endothelial dysfunction recently described in sickle cell disease (18, 19), the idea that hemolysis producing levels of plasma Hb of only 20–150 μM (heme concentration) can significantly affect vascular physiology is not universally accepted. Indeed, a role for Hb in mediating NO scavenging and for the erythrocyte in limiting this process has been challenged on conceptual grounds (20–22). In addition, the primary mechanism for the vasoactivity of cell-free Hb–based blood substitutes remains controversial and has been attributed to both NO scavenging (23) and the premature delivery of oxygen to the systemic arterioles (24, 25), both of which mediate vasoconstriction.

In response to the uncertainty surrounding the relationship between Hb decompartmentalization and NO consumption, we have developed a canine model of intravascular hemolysis to test 3 major hypotheses: (a) simple cellular compartmentalization of Hb within the erythrocyte greatly limits the dioxygenation reaction of Hb with endothelially derived NO; (b) intravascular hemolysis produces a state of resistance to endogenously produced and exogenously delivered NO; and (c) inhaled NO gas will selectively oxidize the plasma HbFeII-O2 to methemoglobin, which will inhibit endogenous NO consumption and systemic vasoconstriction during hemolysis.

Results

Free water–induced intravascular hemolysis produces dose- and time-dependent increases in plasma HbFeII-O2, which stoichiometrically consumes NO and impairs systemic and renal perfusion.

Free water–induced hemolysis produces direct intravascular hemolysis, thereby maintaining the same intravascular concentration of Hb during hemolysis. Only the cellular compartmentalization of the Hb is disrupted in these experiments. Model-building experiments demonstrated that the amount of intravascular hemolysis was dependent on the rate and duration of free water infusion (Figure 1A). Infusion rates of 16 ml/kg/h produced steady rises in plasma Hb to concentrations of 200–300 μM (concentration in terms of heme) over a 6-hour infusion. During hemolysis, total Hb levels were unchanged and hematocrit (Hct) was unchanged, reflecting the fact that levels of plasma Hb of 200 μM represent hemolysis of only 2% of all erythrocytes. In this model, cell-free plasma Hb released from the erythrocytes remained 92% HbFeII-O2, and the plasma oxyhemoglobin concentration (in terms of heme) correlated with increased plasma NO consumption in a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio (Figure 1B).

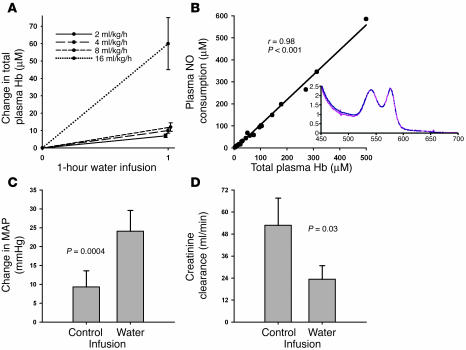

Figure 1.

Characteristics of the canine free water hemolysis model. (A) Increasing rates of free water infusion caused increased rates of hemolysis with higher total plasma Hb levels (concentration in terms of heme groups). (B) The amount of plasma Hb (concentration in terms of heme groups) released by free water–induced intravascular hemolysis remained ferrous (HbFeII-O2) and correlated with the ability of the plasma to consume NO in a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio (r = 0.98; P < 0.001). The inset represents a sample spectrum of the Hb species in the plasma, which demonstrates that the cell-free plasma Hb consists predominantly of oxyhemoglobin. (C and D) Compared with 6-hour control infusions (D5W and normal saline combined), 6-hour infusions of free water caused a significant increase in MAP (C; P = 0.0004) and a significant decrease in 6-hour creatinine clearance (D; P = 0.03) from time 0.

In paired 6-hour pilot experiments, the physiologic responses to 5% dextrose water (D5W) and normal saline were similar (P = NS) and produced no measurable intravascular hemolysis. D5W was chosen as the control fluid for the full-factorial design to control for the hypotonic effects of free water. Consistent with the observed stoichiometric consumption of NO by plasma Hb produced during free water infusion (Figure 1B), free water infusion produced significant increases in mean arterial pressure (MAP) (Figure 1C) and a significant decrease in creatinine clearance over a 6-hour infusion (Figure 1D) compared with control infusions (D5W and normal saline combined).

Effects of hemolysis and inhaled NO on cardiovascular physiology and end-organ function.

In order to test the effects of intravascular hemolysis on systemic perfusion and the role of Hb-based NO scavenging as a mechanism for hemodynamic perturbations, full-factorial experiments were performed using 4 experimental interventions (Figure 2). In these experiments, hemolysis produced increases in MAP and systemic vascular resistance index (SVRI) and a decrease in cardiac index (CI). Consistent with this effect being mediated by NO scavenging by plasma oxyhemoglobin, there was a significant interaction between the presence or absence of hemolysis and the effects of inhaled NO on MAP (P = 0.0003 for interaction of NO and hemolysis; Figures 3 and 4), SVRI (P = 0.0003 for interaction of NO and hemolysis; Figure 4), and CI (P = 0.02 for interaction of NO and hemolysis; data not shown). Inhaled NO attenuated hemolysis-induced increases in MAP and SVRI, and hemolysis induced decreases in CI. In contrast, inhaled NO did not change hemodynamic parameters in nonhemolyzing animals. These data indicate that the effects of inhaled NO during hemolysis were secondary to the direct attenuation of the vasomotor effects of cell-free plasma Hb on the vasculature and not to inhaled NO-induced systemic vasodilatation.

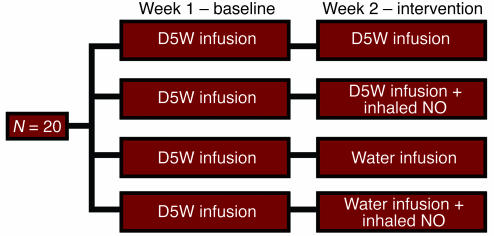

Figure 2.

Full-factorial study design of the effects of intravascular hemolysis and inhaled NO. In order to minimize variability and limit the number of animals necessary to perform these studies, each animal underwent a baseline and intervention experiment. During the first week, each animal underwent a 6-hour baseline study with an infusion of D5W to control for the effects of the fluid challenge. During the second week, animals underwent a 6-hour intervention study in which they were randomized to receive 1 of 4 treatments (D5W; D5W plus inhaled NO; free water; or free water plus inhaled NO). This design allowed for the comparison of differences across treatment groups by subtracting calculated differences within animals (from baseline to intervention) in each treatment group. Comparison of these differences of the differences allowed for analysis of the effects of hemolysis, the effects of inhaled NO, and detection of any interaction between the 2 interventions.

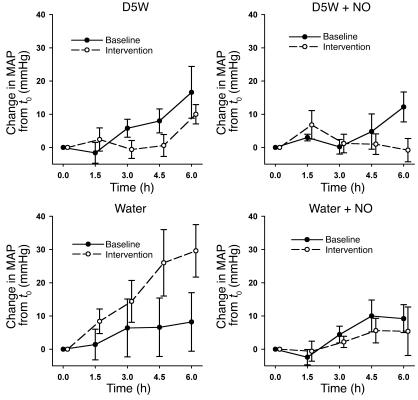

Figure 3.

Effects of hemolysis and inhaled NO on MAP. In paired experiments, all animals received a 6-hour D5W infusion during the baseline study and 1 week later were randomized to a 6-hour intervention study of either D5W, D5W plus NO, free water, or free water plus NO. Changes in MAP over the course of the 6-hour baseline (filled circles) and intervention studies (open circles) are shown. In all 4 groups of animals, there were statistically similar small increases in MAP during the 6-hour baseline D5W infusion. Compared with an equivalent infusion of D5W with or without NO (nonhemolyzing control groups), free water–induced intravascular hemolysis caused a significant increase in MAP, which was attenuated by the concurrent inhalation of NO gas (P = 0.0003 for interaction of NO and hemolysis).

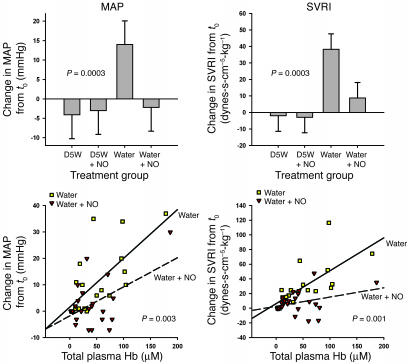

Figure 4.

Relationship between total cell-free plasma Hb and the physiologic effects of hemolysis and inhaled NO. Upper panels: The difference in response from 0 to 6 hours between baseline and intervention studies for each of the 4 treatment groups is shown for MAP and SVRI. In animals receiving D5W (nonhemolyzing control groups), inhaled NO had no net effect on MAP and SVRI. Compared with these nonhemolyzing controls, free water–induced intravascular hemolysis caused significant increases in MAP and SVRI, which were attenuated by the concurrent inhalation of NO gas (P = 0.0003 for interaction of NO and hemolysis for both variables). Lower panels: Relationship between change in MAP and SVRI and total plasma Hb levels (concentration in terms of heme groups) during the intervention studies in the hemolyzing groups (free water and free water plus NO groups). Despite similar total plasma Hb levels in these 2 groups, the relationships between change in MAP and SVRI and total plasma Hb levels were significantly different (P = 0.003 and P = 0.001, respectively). As total plasma Hb levels increased, MAP and SVRI increased more in the free water group than in the free water plus NO group.

The observed increases in total plasma Hb levels were similar in both groups of hemolyzing animals with and without NO gas inhalation. However, the relationship between increasing MAP and total plasma Hb concentration, and SVRI and total plasma Hb, differed based on the administration of NO gas (P = 0.003 and P = 0.001 respectively; Figure 4). Thus, as total plasma Hb levels increased, the associated increase in MAP and SVRI was blunted with NO gas inhalation. These results reveal that exogenous NO attenuates the hemodynamic vasopressor effects of hemolysis without changing cell-free Hb levels. This is consistent with an inhibition of the ability of circulating Hb to scavenge systemic NO in the presence of inhaled NO.

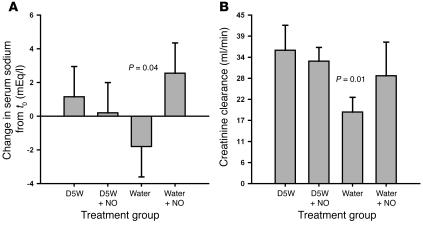

Hemolysis also reduced the ability of the kidneys to compensate for infusion-related hyponatremia and led to a decrease in creatinine clearance. This renal dysfunction was attenuated by inhaled NO (P = 0.04 for interaction of NO and hemolysis and P = 0.01 for ordering of the 4 treatment groups; Figure 5, A and B).

Figure 5.

Effects of hemolysis and inhaled NO on renal function. (A) The difference in response from 0 to 6 hours between baseline and intervention studies for each of the 4 treatment groups is shown for serum sodium levels. Compared with infusion of D5W with or without NO, free water–induced intravascular hemolysis caused a significant impairment in the ability of the kidneys to compensate for hyponatremia, which was attenuated by the concurrent inhalation of NO (P = 0.04). (B) Six-hour creatinine clearance values during the intervention studies for each of the 4 treatment groups are shown. Based on a priori hypotheses, the creatinine clearance values ordered as expected, with the free water group having the lowest clearance, the D5W and D5W plus NO groups having the highest clearances, and the free water plus NO group having an intermediate clearance approaching that of the D5W and D5W plus NO groups (P = 0.01).

In animals receiving free water infusion (with and without NO gas inhalation), plasma haptoglobin levels rapidly decreased to less than 33% of baseline values during the 6-hour infusion (measured by Western blotting; data not shown).

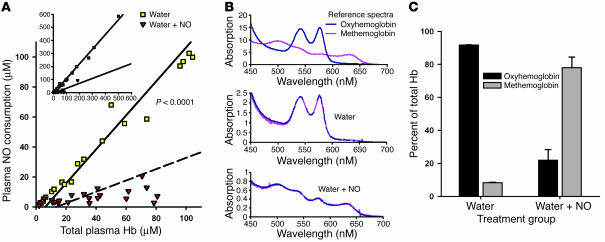

Vasopressor effects of hemolysis are mediated by the dioxygenation reaction of plasma oxyhemoglobin with NO and inhibited by conversion of plasma oxyhemoglobin to methemoglobin during NO inhalation.

During free water–induced hemolysis, plasma NO consumption increased in an approximate 1:1 ratio with total plasma Hb levels (Figure 6A). Spectral deconvolution of the plasma Hb species in hemolyzing animals demonstrated that the plasma Hb was 92% HbFeII-O2. In contrast, in hemolyzing animals treated with inhaled NO, there was limited plasma NO consumption despite increasing total Hb levels. Spectral deconvolution of plasma in these animals revealed that the plasma Hb consisted of predominantly methemoglobin in hemolyzing animals receiving inhaled NO. Therefore, inhaled NO attenuated the physiologic effects of free water–induced intravascular hemolysis by altering the ability of the plasma Hb to react with endogenous NO. During hemolysis, oxyhemoglobin consumes endothelium-derived NO and disrupts vasomotor balance. However, the administration of NO maintains vasomotor tone by converting oxyhemoglobin to methemoglobin, which does not consume endothelium-derived NO.

Figure 6.

Plasma NO consumption and plasma Hb levels. (A) A significantly different relationship exists between plasma NO consumption and total plasma Hb levels (concentration in terms of heme groups) in the free water and free water plus NO groups (P < 0.0001). The inset demonstrates the relationships over the entire range of measured Hb levels, whereas the main graph focuses on the physiologic range of hemolysis in human disease states. (B) Spectral deconvolution of the plasma Hb species. The upper spectrum represents reference tracings for canine oxyhemoglobin and methemoglobin. The middle and lower spectra represent characteristic samples from the free water and free water plus NO treatment groups, respectively. (C) Total plasma Hb composition in the free water and free water plus NO groups was significantly different at 6 hours (P = 0.03). In the free water group, the plasma contained predominantly oxyhemoglobin. In contrast, in the free water plus NO group, the plasma contained predominantly methemoglobin.

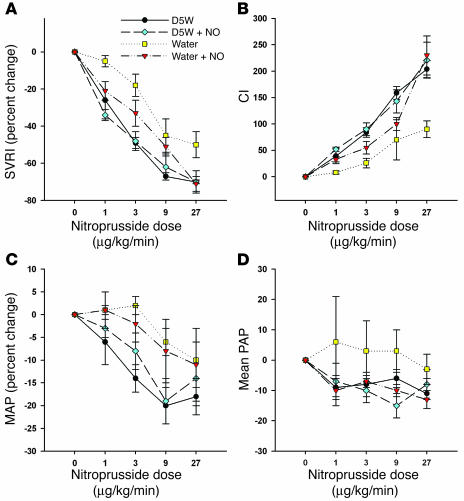

Effects of hemolysis and inhaled NO on hemodynamic responses to sodium nitroprusside, an infused NO donor.

Sodium nitroprusside was administered to all animals during intervention experiments of the full-factorial study of inhaled NO and intravascular hemolysis in order to provide further evidence that plasma Hb released during hemolysis reacts with intravascular NO, thereby leading to systemic vasoconstriction. Sodium nitroprusside decreased SVRI and increased CI in a dose-dependent manner. The presence of hemolysis attenuated the expected vasodilatory response to escalating doses of sodium nitroprusside; however, concomitant inhalation of NO gas restored the expected nitroprusside response toward that of the nonhemolytic controls (P = 0.005 and 0.02 for SVRI and CI, respectively; Figure 7). Similar but not statistically significant patterns of response to increasing doses of sodium nitroprusside in the 4 treatment groups were also demonstrated for MAP, pulmonary artery pressure (PAP), heart rate (HR), central venous pressure (CVP), and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP). In fact, all 7 hemodynamic variables demonstrated the expected ordered responses to nitroprusside (P = 0.008 for 7/7 variables having the same response pattern). These diminished responses of sodium nitroprusside during hemolysis support the hypothesis that cell-free plasma Hb consumes NO within the vasculature during intravascular hemolysis. These results may also, in part, be explained by the direct reaction of sodium nitroprusside with oxyhemoglobin (26).

Figure 7.

Physiologic effects of sodium nitroprusside during hemolysis with and without inhaled NO. Percent change in SVRI (A) and CI (B) in response to increasing doses of sodium nitroprusside during the intervention studies for each of the 4 treatment groups. Compared with D5W and D5W plus NO, free water–induced hemolysis led to blunted hemodynamic effects of escalating doses of sodium nitroprusside, which were restored with inhaled NO therapy and oxidation of plasma Hb (P = 0.005 and P = 0.02 for SVRI and CI, respectively). Similar but not statistically significant patterns of response to increasing doses of sodium nitroprusside in the 4 treatment groups were also demonstrated for MAP (C), PAP (D), heart rate, CVP, and PCWP. In fact, all 7 hemodynamic variables demonstrated the expected ordered responses to nitroprusside (P = 0.008 for 7/7 variables having the same response pattern).

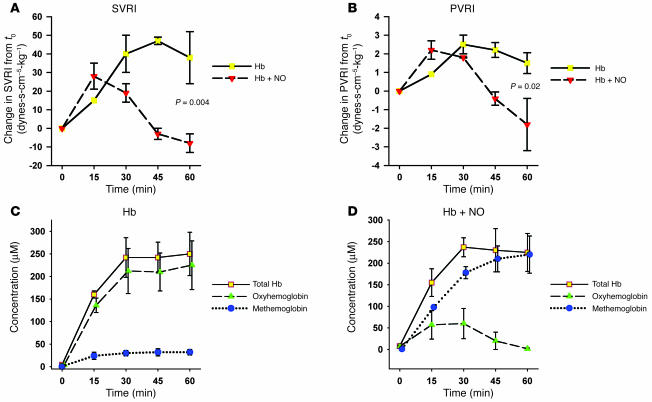

Physiologic effects of Hb infusions are attenuated by inhaled NO.

In a second model using direct infusions of canine Hb preparations, plasma Hb significantly increased SVRI and pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI), and inhaled NO attenuated Hb-induced increases in SVRI and PVRI (Figure 8). In animals breathing air, plasma Hb remained predominantly oxyhemoglobin over the course of the infusion. In contrast, in animals breathing NO, the plasma Hb was converted to predominantly methemoglobin over the course of the infusion. In the animals breathing NO, there was a higher concentration of methemoglobin in the systemic arterial circulation than in the pulmonary circulation (mean difference, 4.5%; 95% confidence interval, –0.6% to 9.7%; P = 0.07), suggesting that the conversion of oxyhemoglobin to methemoglobin was occurring in the pulmonary circulation at the site of NO inhalation.

Figure 8.

Effects of Hb infusions with and without inhaled NO. Infusion of cell-free Hb led to increases in SVRI and pulmonary vascular resistance index that were attenuated by inhaled NO (A and B). In animals breathing air (n = 2), the cell-free Hb remained predominantly oxyhemoglobin (C). In contrast, in animals breathing NO (n = 2), the cell-free Hb was converted to methemoglobin (D).

Discussion

We developed 2 canine models of intravascular hemolysis in order to obtain mechanistic insight into the relationship among cell-free plasma Hb, NO bioavailability, and the systemic manifestations that can occur with Hb-mediated NO consumption. Importantly, in the first model, the total intravascular Hb level is unchanged; only the compartmentalization of Hb within the erythrocyte membrane is disrupted. These experiments demonstrated that hemolysis produces dose-dependent vasoconstriction and impaired renal function secondary to the stoichiometric oxidation of endogenous and exogenous NO by cell-free plasma oxyhemoglobin. Importantly, 80 ppm inhaled NO gas oxidized 85–90% of the plasma oxyhemoglobin to methemoglobin, which inhibited endogenous NO scavenging, prevented systemic vasoconstriction, and restored responsiveness to systemically infused NO donors. This observation confirms that the observed physiological effects of hemolysis are directly mediated by the dioxygenation reaction of ferrous oxyhemoglobin and NO (Reaction 1). These studies provide evidence for the existence of a syndrome of hemolysis-associated endothelial dysfunction and suggest a potential therapeutic role of inhaled NO for iatrogenic, acquired, and hereditary hemolytic diseases. Specifically, the consumption and loss of NO activity during intravascular hemolysis may contribute to clinical signs and symptoms attributable to vasomotor instability that may be ameliorated by NO gas inhalation.

The levels of plasma Hb produced in the present study (with concentration expressed in terms of heme group) are within the ranges observed in human disease states. For example, in patients with sickle cell disease, the levels of plasma oxyheme range from 2 to 20 μM, with mean levels of 4 μM (18). During vasoocclusive crisis, levels can rise to 20–40 μM (27). Intravascular hemolysis in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria produces abdominal pain, gastric and esophageal dystonia, and erectile dysfunction, with levels of plasma Hb ranging from 30 to 120 μM (in heme concentration) and up to 600 μM during paroxysms of hemolysis (28). During cardiopulmonary bypass, the levels of plasma oxyheme can rise to 150 μM (29–32). The present studies suggest that these pathologically relevant levels of hemoglobinemia may be associated with endogenous NO inhibition, a vasopressor effect, and impaired organ function.

The biochemical and physiologic disturbances that occur during intravascular hemolysis are related to the disruption of diffusional barriers that typically regulate the reaction of intra-erythrocytic Hb with NO (11–17). Cell-free plasma Hb can react with endothelial cell–produced NO at nearly diffusion-limited rates, resulting in the rapid dioxygenation of NO by Hb with the formation of nitrate and methemoglobin (6–9). These rapid reactions greatly limit the diffusion of NO from endothelium to smooth muscle. Consequently, smooth muscle guanylyl cyclase is not activated, and vascular relaxation and vasodilation are inhibited (33). Additionally, cell-free plasma Hb can rapidly extravasate into the spaces between endothelial and smooth muscles cells and further scavenge NO, thereby prohibiting it from diffusing into smooth muscle cells (10). This mechanism is supported by the observed decrease in hypertensive effects of the Hb-based blood substitutes as molecular weight increases (7, 23) and the decrease in NO scavenging effects of the high-molecular-weight haptoglobin-Hb complex, compared with non–haptoglobin-bound Hb (34). We have proposed that the formation of Hb-haptoglobin high-molecular-weight multimers serves to limit such extravasation during physiologic intravascular hemolysis (35).

NO scavenging by cell-free plasma Hb may have contributed to the increased morbidity and mortality observed in studies of stroma-free Hb artificial blood substitute solutions (7). The administration of the blood substitute solutions in preclinical and clinical trials led to pulmonary and systemic hypertension, increased systemic vascular resistance, decreased organ perfusion, gastrointestinal spasm and dysmotility, and death (7, 36–43). While studies of new generation Hb-based blood substitutes with heme pocket mutations designed to decrease the heme reactivity with NO have shown reduced vasopressor effects (6), other investigators have suggested that the vasoconstrictor effects of Hb-based blood substitutes occur secondarily to premature oxygen unloading at the precapillary sphincter (24, 25). The current study provides additional evidence that NO consumption by oxyhemoglobin is a mechanism of cell-free Hb–mediated vasoconstriction and may contribute to the adverse effects observed in the blood substitute trials and during intravascular hemolysis in human disease.

In chronic hereditary hemolytic diseases such as sickle cell anemia, clinical complications such as pulmonary hypertension, priapism, leg ulcerations, and stroke may be in part related to repeated episodes of intravascular hemolysis with consequent increased NO scavenging, vasoconstriction, and end-organ hypoperfusion (18, 19, 44). In patients with sickle cell disease, chronic hemolysis leads to the destruction of approximately 10% of the circulating erythrocytes every 24 hours, with 30% of this hemolysis estimated to be intravascular (18, 45). The Hb scavenging system in these patients becomes saturated, as indicated by undetectable plasma haptoglobin levels, and cell-free plasma Hb accumulates, as has been demonstrated by increased levels of plasma Hb in patients with sickle cell disease compared with normal patients (18). The plasma of these patients consumes significantly more NO than the plasma of normal patients, and the amount of NO consumption correlates with the plasma heme levels (18). Consistent with an NO-scavenging effect of increased cell-free plasma Hb, the vasodilatory responses to nitroprusside, nitroglycerin, and other NO donors are significantly blunted in sickle cell patients and in sickle cell transgenic mouse models (18, 19, 46–48). Scavenging of NO by cell-free plasma Hb may be involved in the pathophysiologic vasculopathy and prothrombotic state that occur in many chronic hereditary hemolytic diseases such as sickle cell disease and thalassemia (18, 19, 46–54) and acute hemolytic disease states, such as prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, and malaria. These studies provide further evidence that inhaled NO therapy may attenuate the NO-scavenging effects of cell-free plasma Hb and may be able to block the pathophysiologic changes that occur during iatrogenic (cardiopulmonary bypass) or disease-specific (sickle cell pain crisis, malaria, etc.) intravascular hemolysis in many human diseases. Further research is required to assess the contribution of hemolysis and therapeutic utility of inhaled NO therapy in hereditary and iatrogenic hemolytic disorders.

In conclusion, these data provide controlled in vivo evidence that NO scavenging by cell-free plasma Hb during intravascular hemolysis disrupts endothelial NO-dependent vasomotor function and produces systemic physiologic changes and organ dysfunction, which are attenuated by inhaled NO therapy. These biochemical and physiological studies support the existence of a syndrome of hemolysis-associated endothelial dysfunction, which may contribute to the vasculopathy of hereditary, acquired, and iatrogenic hemolytic states. Furthermore, these studies support a potential therapeutic role for NO donor agents in preventing the end-organ injury associated with these disease states.

Methods

Experimental design.

All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Clinical Center of the NIH. In all, 32 purpose-bred beagles (12–28 months, 9–12 kg) were studied.

All procedures were performed after the induction of anesthesia with halothane (1–4%) and the initiation of mechanical ventilation. Once all procedures were finished, the halogenated gas was terminated, and 100% oxygen administered until the dog emerged from anesthesia. The dog was then maintained on continuous sedation with intravenous medetomidine (2–5 μg/kg/h) and received continuous intravenous analgesia with fentanyl (5–15 μg/kg/h). The animals were monitored continuously, and all signs of pain and distress were evaluated immediately and the infusions adjusted appropriately.

Model development.

A canine model of free water–induced intravascular hemolysis was developed to determine the optimal dose of free water administration that produced clinically relevant levels of cell-free plasma Hb (20–300 μM heme), simulating an acute hemolytic episode. Increasing rates of free water (2, 4, 8, 16 ml/kg/h) were administered intravenously through a central venous catheter to 4 animals over 6 hours in order to characterize the relationship between the rate of free water infusion and plasma concentration of cell-free Hb. Subsequent experiments were performed (n = 8) to determine the ideal control fluid to be used in the full-factorial design as well as to delineate the biochemical and pathophysiologic effects of acute intravascular hemolysis in our model. In these pilot experiments, each animal received a 6-hour baseline infusion of 1 of 2 potential control group fluids through the central venous catheter (n = 4, 0.9% sodium chloride; n = 4, D5W) followed 1 week later by a 6-hour infusion of free water through a central venous catheter. Based on these pilot experiments, a free water infusion rate of 16 ml/kg/h was chosen to achieve the desired rate of intravascular hemolysis. While there was no difference in the hemodynamic responses to either control fluid, 0.9% sodium chloride or D5W, we chose the latter to control for any potential hypotonic effects of free water infusion.

Full-factorial study design.

This set of experiments examined the effects of inhaled NO gas and oxidation of plasma oxyhemoglobin to methemoglobin on the biochemical and physiologic changes caused by intravascular hemolysis. Paired experiments were performed in 20 tracheostomized animals (5 per group) and included a 6-hour baseline study with infusion of D5W through a central venous catheter followed 1 week later by a 6-hour intervention study with infusion of either D5W or free water through a central venous catheter with or without inhaled NO (Figure 1). All animals received 21% fraction inspired oxygen (FiO2) through tracheostomy using an air/oxygen blender. Eighty ppm NO gas with 21% FiO2 was simultaneously administered to animals randomized to receive NO therapy. In order to determine the vascular responsiveness to exogenous NO in the presence and absence of hemolysis and inhaled NO, all animals received a 20-minute infusion of escalating doses of sodium nitroprusside, a direct NO donor (1, 3, 9, and 27 μg/kg/min) at 5-minute intervals prior to the conclusion of the study.

Data collection.

For all studies, femoral arterial (20-gauge) and external jugular venous (8 French) catheters (Maxxim Medical) were placed percutaneously under anesthesia using aseptic sterile technique. MAP and HR were obtained from the femoral artery catheter tracing. Additionally, a pulmonary artery thermodilution catheter (7 French; Abbott Critical Care Systems, Abbott Laboratories) was introduced through the external jugular vein catheter in order to obtain cardiac output (CO), CI, PAP, PCWP, and CVP measurements. Urinary catheters (12 French) were placed during each study under anesthesia using aseptic technique. All catheter placements were performed under general anesthesia. At the end of the first week’s fluid control experiments, all catheters were removed, and the animals recovered. At the end of the second week’s intervention experiments, all animals were euthanized.

In all experiments, hemodynamic measurements (MAP, CVP, PAP, CO, and PCWP) and laboratory studies (analysis of Hct, Hb, and serum chemistries; arterial blood gas analysis; spectrophotometric-based quantification of cell-free Hb concentration; and chemiluminescence-based assays of NO consumption) were obtained at 0-, 1.5-, 3.0-, 4.5-, and 6.0-hour time points. Urine was collected from 0 to 6 hours to measure 6-hour creatinine clearances. Hemodynamic measurements were also obtained at the end of each 5-minute interval of sodium nitroprusside infusion at doses of 1, 3, 9, and 27 μg/kg/min.

Confirmatory Hb infusion experiments.

The contribution of cell-free Hb to the physiologic findings in our water infusion model cannot be completely isolated, because this model simulates an acute episode of intravascular hemolysis with the release of erythrocyte membrane and all cellular contents into the plasma. Also, the hypotonic swelling of the erythrocytes in our model does not always lead to cell lysis and may have contributed to the physiologic alterations in our model. Therefore, to confirm and extend the findings of the intravascular water infusion model, additional experiments were performed with infusion of 99% pure Hb solutions directly into the animals. Canine whole blood was collected and diluted with PBS buffer (1:2). The blood was frozen and thawed 3 times and then centrifuged at 82,000 g for 1 hour at 4°C to remove the membrane fraction. The supernatant was collected and filtered (0.22 μM). Hb concentrations were measured, and the solutions were stored at 4°C until infusion. Prior to infusion, each solution underwent a second filtration (0.22 μM). These additional experiments allowed for direct measurements of the physiologic and biochemical effects of cell-free Hb infusion with and without inhaled NO exposure. Hb solutions were infused into animals breathing air (n = 2) or 80 ppm NO (n = 2) for 1 hour. Serial physiologic and biochemical measurements were obtained.

Plasma Hb, NO consumption, and haptoglobin assays.

The ability of plasma to consume NO was measured with a previously published and validated NO consumption assay using an NO chemiluminescence analyzer (Sievers 280i NO analyzer; GE Analytical Instruments) as previously described (35). Total plasma Hb concentration (expressed in terms of heme groups; division by 4 gives Hb concentration) was measured by visible absorbance spectrophotometry (HP8453 UV-Vis Diode Array Spectrophotometer; Hewlett-Packard). The concentrations of oxyhemoglobin and methemoglobin were analyzed by deconvoluting the spectrum into components from basis spectra of canine Hb composed of oxyhemoglobin and methemoglobin in PBS buffer using a least-square method similar to that previously described, with subtraction of background plasma scattering (55). Plasma haptoglobin levels were measured using a polyclonal anti-human haptoglobin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) as previously described (18).

Statistics.

Pilot data were analyzed using ANOVA, with main effects for study (baseline and hemolysis), time, and animal, and a 2-way interaction between study and time. The full-factorial treatment experiments were analyzed using ANOVA, with main effects for study (baseline and intervention), 4 treatment arms, time, and animal (nested within each of the 4 arms). Two- and 3-way interactions, not involving animal, were included in the model. Analysis of responses to sodium nitroprusside were performed using ANOVA on percent change in hemodynamic variables with increasing dose in the intervention study with main effects for the 4 treatment arms, dose, and animal (nested within each of the 4 arms). Two-way interactions, not involving animal, were included in the model. Analysis of differences in creatinine clearance during the intervention study was performed using a nonparametric test for ordered alternatives based on the a priori hypothesis that free water would decrease creatinine clearance and that inhaled NO would attenuate this decrease (Jonckheere-Terpstra test) (56). Comparisons of the 2 groups of animals in the confirmatory Hb infusion experiments were performed with ANOVA with main effects for treatment group and time and a 2-way interaction term. All values are represented in the figures as mean ± SEM, and all Hb concentrations are expressed in terms of heme groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by intramural sources at the NHLBI and the Critical Care Medicine Department, Clinical Center at the NIH. We gratefully thank INO Therapeutics for supplying the NO gas and delivery systems for this study.

Footnotes

Peter C. Minneci and Katherine J. Deans contributed equally to this work.

Mark T. Gladwin and Steven B. Solomon are co-senior authors.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: CI, cardiac index; CVP, central venous pressure; D5W, 5% dextrose water; Hb, hemoglobin; HbFeII-O2, ferrous oxyhemoglobin; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; SVRI, systemic vascular resistance index.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Furchgott RF, Zawadzki JV. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature. 1980;288:373–376. doi: 10.1038/288373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ignarro LJ, Buga GM, Wood KS, Byrns RE, Chaudhuri G. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor produced and released from artery and vein is nitric oxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1987;84:9265–9269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ignarro LJ, Byrns RE, Buga GM, Wood KS. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor from pulmonary artery and vein possesses pharmacologic and chemical properties identical to those of nitric oxide radical. Circ. Res. 1987;61:866–879. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.6.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer RM, Ferrige AG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature. 1987;327:524–526. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmer RM, Ashton DS, Moncada S. Vascular endothelial cells synthesize nitric oxide from L-arginine. Nature. 1988;333:664–666. doi: 10.1038/333664a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doherty DH, et al. Rate of reaction with nitric oxide determines the hypertensive effect of cell-free hemoglobin. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998;16:672–676. doi: 10.1038/nbt0798-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dou Y, Maillett DH, Eich RF, Olson JS. Myoglobin as a model system for designing heme protein based blood substitutes. Biophys. Chem. 2002;98:127–148. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gladwin MT, Lancaster JR, Freeman BA, Schechter AN. Nitric oxide’s reactions with hemoglobin: a view through the SNO-storm. Nat. Med. 2003;9:496–500. doi: 10.1038/nm0503-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schechter AN, Gladwin MT. Hemoglobin and the paracrine and endocrine functions of nitric oxide. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1483–1485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr023045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakai K, et al. Inhibition of endothelium-dependent relaxation by hemoglobin in rabbit aortic strips: comparison between acellular hemoglobin derivatives and cellular hemoglobins. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1996;28:115–123. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199607000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaughn MW, Kuo L, Liao JC. Effective diffusion distance of nitric oxide in the microcirculation. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:H1705–H1714. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.5.H1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butler AR, Megson IL, Wright PG. Diffusion of nitric oxide and scavenging by blood in the vasculature. . Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998; 1425:168–176. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao JC, Hein TW, Vaughn MW, Huang KT, Kuo L. Intravascular flow decreases erythrocyte consumption of nitric oxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:8757–8761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coin JT, Olson JS. The rate of oxygen uptake by human red blood cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:1178–1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, et al. Diffusion-limited reaction of free nitric oxide with erythrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:18709–18713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaughn MW, Huang KT, Kuo L, Liao JC. Erythrocytes possess an intrinsic barrier to nitric oxide consumption. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:2342–2348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang KT, et al. Modulation of nitric oxide bioavailability by erythrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:11771–11776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201276698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reiter CD, et al. Cell-free hemoglobin limits nitric oxide bioavailability in sickle-cell disease. Nat. Med. 2002;8:1383–1389. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaul DK, Liu XD, Chang HY, Nagel RL, Fabry ME. Effect of fetal hemoglobin on microvascular regulation in sickle transgenic-knockout mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:1136–1145. doi:10.1172/JCI200421633. doi: 10.1172/JCI21633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gow AJ, Luchsinger BP, Pawloski JR, Singel DJ, Stamler JS. The oxyhemoglobin reaction of nitric oxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:9027–9032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaston BM, Hare JM. Hemoglobin and nitric oxide [letter] N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:402–405; author reply 402–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pawloski JR. Hemoglobin and nitric oxide [letter] N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:402–405; author reply 402–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olson JS, et al. NO scavenging and the hypertensive effect of hemoglobin-based blood substitutes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004;36:685–697. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rohlfs RJ, et al. Arterial blood pressure responses to cell-free hemoglobin solutions and the reaction with nitric oxide. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:12128–12134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarthy MR, Vandegriff KD, Winslow RM. The role of facilitated diffusion in oxygen transport by cell-free hemoglobins: implications for the design of hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers. Biophys. Chem. 2001;92:103–117. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(01)00194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kruszyna H, Kruszyna R, Rochelle LG, Smith RP, Wilcox DE. Effects of temperature, oxygen, heme ligands and sulfhydryl alkylation on the reactions of nitroprusside and nitroglycerin with hemoglobin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1993;46:95–102. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90352-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naumann HN, Diggs LW, Barreras L, Williams BJ. Plasma hemoglobin and hemoglobin fractions in sickle cell crisis. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1971;56:137–147. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/56.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartmann RC, Jenkins DE, Jr, McKee LC, Heyssel RM. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: clinical and laboratory studies relating to iron metabolism and therapy with androgen and iron. Medicine (Baltimore). 1966;45:331–363. doi: 10.1097/00005792-196609000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis CL, Kausz AT, Zager RA, Kharasch ED, Cochran RP. Acute renal failure after cardiopulmonary bypass in related to decreased serum ferritin levels. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1999;10:2396–2402. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10112396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murakami F, et al. Clinical study of totally roller pumpless cardiopulmonary bypass system. Artif. Organs. 1997;21:803–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1997.tb03747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pepper JR, Mumby S, Gutteridge JM. Transient iron-overload with bleomycin-detectable iron present during cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. Free Radic. Res. 1994;21:53–58. doi: 10.3109/10715769409056556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimono T, et al. Silicone-coated polypropylene hollow-fiber oxygenator: experimental evaluation and preliminary clinical use. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1997;63:1730–1736. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pohl U, Lamontagne D. Impaired tissue perfusion after inhibition of endothelium-derived nitric oxide. Basic Res. Cardiol. 1991;86(Suppl. 2):97–105. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72461-9_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edwards DH, Griffith TM, Ryley HC, Henderson AH. Haptoglobin-haemoglobin complex in human plasma inhibits endothelium dependent relaxation: evidence that endothelium derived relaxing factor acts as a local autocoid. Cardiovasc. Res. 1986;20:549–556. doi: 10.1093/cvr/20.8.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, et al. Biological activity of nitric oxide in the plasmatic compartment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:11477–11482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402201101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winslow RM. alphaalpha-crosslinked hemoglobin: was failure predicted by preclinical testing? Vox Sang. 2000;79:1–20. doi: 10.1159/000031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hess JR, MacDonald VW, Brinkley WW. Systemic and pulmonary hypertension after resuscitation with cell-free hemoglobin. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993;74:1769–1778. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.4.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hess JR, Macdonald VW, Gomez CS, Coppes V. Increased vascular resistance with hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers. Artif. Cells Blood Substit. Immobil. Biotechnol. 1994;22:361–372. doi: 10.3109/10731199409117867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.LaMuraglia GM, et al. The reduction of the allogenic transfusion requirement in aortic surgery with a hemoglobin-based solution. J. Vasc. Surg. 2000;31:299–308. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(00)90161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lamy ML, et al. Randomized trial of diaspirin cross-linked hemoglobin solution as an alternative to blood transfusion after cardiac surgery. The DCLHb Cardiac Surgery Trial Collaborative Group. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:646–656. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200003000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Przybelski RJ, et al. Phase I study of the safety and pharmacologic effects of diaspirin cross-linked hemoglobin solution. Crit. Care Med. 1996;24:1993–2000. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199612000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Savitsky JP, Doczi J, Black J, Arnold JD. A clinical safety trial of stroma-free hemoglobin. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1978;23:73–80. doi: 10.1002/cpt197823173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sloan EP, et al. Diaspirin cross-linked hemoglobin (DCLHb) in the treatment of severe traumatic hemorrhagic shock: a randomized controlled efficacy trial. JAMA. 1999;282:1857–1864. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.19.1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nolan, V.G., Wyszynski, D.F., Farrer, L.A., and Steinberg, M.H. 2005. Hemolysis associated priapism in sickle cell disease. Blood. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-04-1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Bensinger TA, Gillette PN. Hemolysis in sickle cell disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 1974;133:624–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaul DK, Liu XD, Fabry ME, Nagel RL. Impaired nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation in transgenic sickle mouse. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000;278:H1799–H1806. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.6.H1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eberhardt RT, et al. Sickle cell anemia is associated with reduced nitric oxide bioactivity in peripheral conduit and resistance vessels. Am. J. Hematol. 2003;74:104–111. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nath KA, et al. Mechanisms of vascular instability in a transgenic mouse model of sickle cell disease. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2000;279:R1949–R1955. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.6.R1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aessopos A, et al. Pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure in patients with beta- thalassemia intermedia. Chest. 1995;107:50–53. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Du ZD, Roguin N, Milgram E, Saab K, Koren A. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with thalassemia major. Am. Heart J. 1997;134:532–537. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Derchi G, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with thalassemia major [letter] Am. Heart J. 1999;138:384. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grisaru D, et al. Cardiopulmonary assessment in beta-thalassemia major. Chest. 1990;98:1138–1142. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.5.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koren A, Garty I, Antonelli D, Katzuni E. Right ventricular cardiac dysfunction in beta-thalassemia major. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1987;141:93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zakynthinos E, et al. Pulmonary hypertension, interstitial lung fibrosis, and lung iron deposition in thalassaemia major. Thorax. 2001;56:737–739. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.9.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang Z, et al. Nitric oxide binding to oxygenated hemoglobin under physiological conditions. . Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001; 1568:252–260. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(01)00227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lehmann, E.L. 1975. Nonparametrics: statistical methods based on ranks. Holden-Day. San Francisco, California, USA. 457 pp.