The national chief of the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples is “pleasantly surprised” by a new Statistics Canada survey dealing with the health of off-reserve Aboriginal people, but it's not the results that surprised Chief Dwight Dorey — it's the fact that the study was done. Although 800 000 Aboriginal Canadians live off reserves and only 230 000 live on them, Dorey said it is the latter population that is usually studied. His group represents off-reserve Indians and Métis people living across Canada.

The 2000/01 Canadian Community Health Survey, The Health of the Off- reserve Aboriginal Population, found that natives living away from reserves are more likely to have chronic health conditions and long-term restrictions on their activity levels than their non- Aboriginal counterparts. They are also more likely to be depressed.

The survey determined that 60.1% of off-reserve natives reported having at least 1 chronic condition, compared with 49.6% of their non-Aboriginal counterparts. The 3 most prevalent conditions were arthritis (26.4%), hypertension (15.4%) and diabetes (8.7%), with diabetes being twice as common as in the non-Aboriginal population; 23.1% of off-reserve Aboriginal people perceived their health as being only fair or poor, a rate 1.9 times higher than in the non-Aboriginal population.

The survey also looked at health determinants and found that the off-reserve population had lower levels of education (43.9% of respondents had not graduated from high school, compared with 23.1% of non-Aboriginal Canadians) and income. More of them smoked (51.4% vs. 26.5%), were obese (24.7% vs. 14.0%) and were heavy drinkers (22.6% vs. 16.1%). On the positive side, more had quit drinking alcohol (22.7% vs. 11.9%).

Aboriginals living on reserves have concerns similar to those living off them: 8% of men have diabetes, and 44% of people live below the poverty line.

Dorey speculates that “a culture of despair” may be at the root of some of his community's difficulties. Part of the problem, he said, is that governments do not accept responsibility for off-reserve native people. “In some ways, Aboriginal peoples off reserve are in the worst of all possible positions — we carry the unhealthy legacy of Aboriginal policies and dysfunctional backgrounds, without the support and encouragement of an Aboriginal community around us.”

And not only do studies tend to focus on natives who live on reserves, a large percentage of government funding is directed at them. Of the $58 million in a 5-year federal program aimed at combating diabetes among Aboriginal people, the congress says that only $14.5 million is being spent on the off-reserve population.

Dorey said the report is welcome because it focuses on people who are often forgotten. “This will help make Canadians more aware of what the real situation is.” — Barbara Sibbald, CMAJ

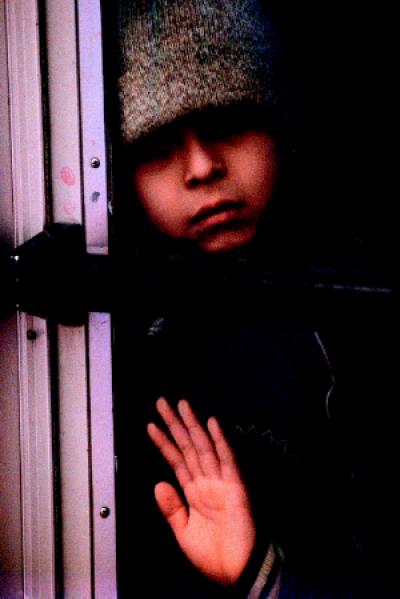

Figure. A forgotten population? Photo by: Health Canada