Abstract

Objectives To quantify and compare potential benefits (subjective reports of sleep variables) and risks (adverse events and morning-after psychomotor impairment) of short term treatment with sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia.

Data sources Medline, Embase, the Cochrane clinical trials database, PubMed, and PsychLit, 1966 to 2003; bibliographies of published reviews and meta-analyses; manufacturers of newer sedative hypnotics (zaleplon, zolpidem, zopiclone) regarding unpublished studies.

Selection criteria Randomised controlled trials of any pharmacological treatment for insomnia for at least five consecutive nights in people aged 60 or over with insomnia and otherwise free of psychiatric or psychological disorders.

Results 24 studies (involving 2417 participants) with extractable data met inclusion and exclusion criteria. Sleep quality improved (effect size 0.14, P < 0.05), total sleep time increased (mean 25.2 minutes, P < 0.001), and the number of night time awakenings decreased (0.63, P < 0.001) with sedative use compared with placebo. Adverse events were more common with sedatives than with placebo: adverse cognitive events were 4.78 times more common (95% confidence interval 1.47 to 15.47, P < 0.01); adverse psychomotor events were 2.61 times more common (1.12 to 6.09, P > 0.05), and reports of daytime fatigue were 3.82 times more common (1.88 to 7.80, P < 0.001) in people using any sedative compared with placebo.

Conclusions Improvements in sleep with sedative use are statistically significant, but the magnitude of effect is small. The increased risk of adverse events is statistically significant and potentially clinically relevant in older people at risk of falls and cognitive impairment. In people over 60, the benefits of these drugs may not justify the increased risk, particularly if the patient has additional risk factors for cognitive or psychomotor adverse events.

Introduction

Insomnia often affects the quality of life for older people.1-3 Acute episodes are usually treated with drugs.4 Between 5% and 33% of elderly people in North America and the United Kingdom are prescribed a benzodiazepine or a benzodiazepine receptor agonist (zolpidem, zopiclone, zaleplon) for sleep problems.5,6

Adverse events that are associated with sedative use, such as ataxia, falls, or memory impairment, are thought to be particularly detrimental for older people.7,8 Despite the widespread use of sedative hypnotics in older people, the risk-benefit relation is not known. This meta-analysis aims to study the benefits of sedative use, as determined by subjective reported changes in sleep variables, and the risks, as determined by adverse events.

Methods

Identification of studies

We searched Medline, Embase, the Cochrane clinical trials database, PubMed, and PsychLit from 1966 to 2003, using the keywords “elderly” or “aged” (Medline and Cochrane database only) and “sedatives” or “hypnotics” or “benzodiazepines” or “zolpidem” or “zaleplon” or “zopiclone” or “antihistamines” (PsychLit and Cochrane database only) or “diphenhydramine” or “sleep” (Cochrane database only) or “sleep disorders” (PsychLit and Cochrane database only). For each citation identified, we scanned titles or abstracts, or both, to identify randomised controlled trials that excluded patients under 60 years old. If studies included some patients who were under 60 years old, the mean age of participants had to be over 60. We searched bibliographies of published reviews and meta-analyses for relevant titles and asked Servier, Canada (manufacturer of zaleplon), Sanofi-Synthelab, US (maker of zolpidem), and ICN Canada (maker of zopiclone) about unpublished studies.

Inclusion criteria

We considered published randomised controlled trials of sedative hypnotics in English that compared active treatment against placebo or another active comparator. The active treatment phases of included studies were double blind.

In the included studies, participants had a mean age of at least 60 years and met predetermined diagnostic criteria for insomnia. Any study that included diagnostic criteria that were defined a priori was accepted.

Investigators must have excluded patients with psychiatric disorders, concurrent use of drugs affecting the central nervous system, and severe or acute physical illnesses that might disrupt sleep. As outcomes were subjective reports made by patients, investigators must have deemed that participants were cognitively able to perform the assessments (for example, by reporting appropriate score on a scale such as the mini-mental state examination9). Participants must have had a washout period after previous drug treatments, and studies with crossover designs need an appropriate washout period.

Interventions were pharmacological treatments for insomnia for at least five consecutive nights. Any sedative hypnotic currently used in clinical practice was included in the search, including over the counter medications such as antihistamines and prescription medications such as benzodiazepines and zolpidem, zopiclone, and zaleplon. We excluded studies of barbiturates and chloral hydrate or chloral hydrate derivatives as these are not recommended for elderly people.4,10

Study selection, data abstraction, and assessment of quality

Articles were selected on the basis of the inclusion criteria (JG) and verified by another investigator (UEB). Studies were included if data from at least one of the outcome variables could be extracted. Three investigators rated study quality using Jadad criteria,11 of whom two were blinded with respect to authors, author affiliation, date, and source of publication. Method of randomisation and allocation concealment were evaluated at this time while assessing the quality of the study. Two investigators (JG, UEB) abstracted data; UEB was blind to journal, authors, and date of publication. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus.

Outcome measures

Benefits were measured by the participants' perceived change in sleep. The variables that we considered were sleep quality (soundness or depth of sleep); total sleep time (total amount of time participants perceive that they have slept, measured in minutes); sleep onset latency (measured in minutes) or ease of getting to sleep (qualitative measure, score on questionnaire); and number of awakenings during the night. Ratings were made by patients and not an observer. All variables were analysed separately.

To measure risks, we determined the total number of adverse events for treatment and placebo (including placebo run-in phases) and then categorised them as: cognitive adverse events (memory loss, confusion, disorientation); psychomotor-type adverse events (reports of dizziness, loss of balance, or falls); and morning hangover effects (residual morning sedation). We analysed morning impairment (as measured by performance tasks such as reaction time or hand-eye coordination tasks) separately from adverse events as a risk of sedative use.

Data synthesis

As no standard accepted instrument measures sleep quality, we used effect sizes of the change in scores. The equation for Cohen's d was used to estimate effect size: M1-M2/δ (where M1 = mean sleep quality score for the treatment group, M2 = mean sleep quality score for the control group, and δ = pooled standard deviations from either control or treatment or both groups). To minimise false positive results, we used the larger standard error, whether in the control group, treatment group, or all participants pooled. As more than one instrument had been used to measure psychomotor impairment, we also calculated effect sizes for morning-after performance. We assessed total sleep time, number of awakenings, and sleep onset latency as continuous variables.

If means were reported without variances, estimates were obtained from studies with similar methodology and patient population and a similar or smaller sample size.12 If the study did not have a placebo arm but did have a placebo run-in period, we used the run-in period as the control to preserve as much raw data as possible.

We obtained common odds ratios for all adverse events. All results used random effects models and 95% confidence intervals. We used χ2 analysis to test heterogeneity for all combined results.

We calculated numbers needed to treat and to harm by using the inverse of the absolute risk reduction (efficacy data) and the absolute risk increase (adverse event data).13,14

To assess publication bias and heterogeneity, we used funnel plots and Begg and Mazumdars' rank correlation test for all primary outcomes.15,16 If publication bias was detected, we used the “trim and fill” method to adjust the funnel plot and recalculated the results.17

Results

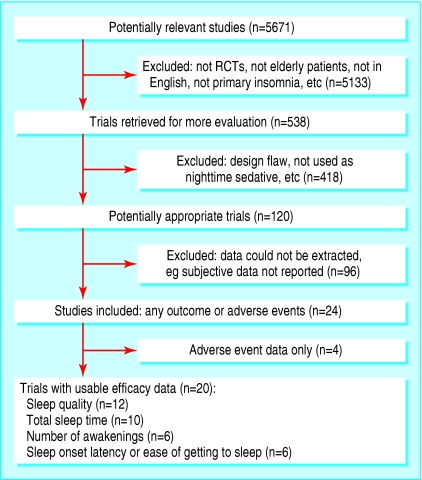

Of 120 studies identified, 20 satisfied inclusion and exclusion criteria and had extractable subjective data.18-37 Four further studies reported on adverse events only and have been included in the assessment of risk (fig 1).38-41

Fig 1.

Flowchart for identification of studies

A total of 830 participants were treated with a benzodiazepine, 106 with zopiclone, 384 with zolpidem, 609 with zaleplon, 14 with diphenhydramine, and 468 with placebo (not including placebo run-ins) (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Quality score* | No | Drug dose, length of treatment | Study population | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancoli-Israel 199918 | 4 | 549 | Zaleplon 5 mg, 10 mg; zolpidem 5 mg, 14 nights | Age range 65-91 (mean 71.67); outpatients; placebo responders excluded (enriched sample) | Parallel, multicentre |

| Bayer et al, 198319 | 3 | 40 | Loprazolam 1 mg, nitrazepam 5 mg, 7 nights | Age range 70-88 (mean 75.5); hospital inpatients, enriched sample | Parallel, single centre |

| Bayer et al, 198620 | 4 | 53 | Loprazolam 0.5 mg, 1 mg, 5 nights | Age range 68-89 (mean 77.8); hospital inpatients | Parallel, single centre |

| Bayer et al, 198638 | 4 | 53 | Triazolam 0.125 mg, chlormethiazole 384 mg, 9 weeks | Age range 70-91, nursing home and hospital inpatients | Parallel, single centre |

| Caldwell et al, 198239 | 4 | 57 | Quazepam 15 mg, 5 nights | Age range 60-81, outpatients | Parallel, single centre |

| Dehlin et al, 198321 | 3 | 40 | Triazolam 0.25 mg; nitrazepam 5 mg, 14 nights | Age range 66-91 (mean 83); residents of home for aged and hospital inpatients | Crossover, washout 7 nights, multicentre |

| Dehlin et al, 199522 | 3 | 107 | Zopiclone 5 mg, flunitrazepam 1 mg, 14 nights | Age range 60-95 (mean 79); “geriatric clinic” patients | Parallel, multicentre |

| Elie et al, 199023 | 2 | 44 | Zopiclone, triazolam (dose adjusted to response), 21 nights | Age range 60-90 (mean 76); residents in homes for aged | Parallel, single centre |

| Fairweather et al, 199224 | 2 | 24 | Zolpidem 5 mg, 10 mg, 7 nights | Age range 63-80 (mean 71); outpatients | Crossover, washout 7 nights, single centre |

| Hedner et al, 200025 | 2 | 437 | Zaleplon, 5 mg, 10 mg, 14 nights | Age range 59-95 (mean 72.5); outpatients | Parallel, multicentre |

| Klimm et al, 198726 | 4 | 74 | Zopiclone 7.5 mg, nitrazepam 5 mg, 7 nights | Mean age 73.2; outpatients | Parallel, single centre |

| Lachnit et al, 198327 | 4 | 46 | Midazolam 15 mg, Vesperax†, 5 nights | Age range 57-90 (mean age 77); inpatients | Parallel, single centre |

| Leppik et al, 199728 | 4 | 335 | Zolpidem 5 mg, triazolam 0.125 mg, temazepam 15 mg, 28 nights | Age range 59-85 (mean 69); participant characteristics not reported | Parallel, multicentre |

| Mamelak et al, 198929 | 4 | 36 | Brotizolam 0.25 mg, flurazepam 15 mg, 14 nights | Age range 60-72, participants' characteristics not reported | Parallel, single centre |

| Meuleman et al, 198730 | 3 | 17 | Temazepam 15 mg, diphenhydramine 50 mg, 5 nights | Age range 56-97 (mean 71.1); nursing home patients | Crossover, washout 72 hr, single centre |

| Morin et al, 199931 | 4 | 40 | Temazepam 7.5-30 mg (dose adjusted to response), 2-7 times per week, 8 weeks | Mean age 65, outpatients | Parallel, single centre |

| Mouret et al, 199040 | 4 | 10 | Triazolam 0.25 mg, zopiclone 7.5 mg, 15 nights | Mean age 68.1, outpatients | Parallel, single centre |

| Murphy et al, 198232 | 6 | 18 | Nitrazepam 2.5 mg, triazolam 0.125 mg, 5 nights | Mean age 80.1; inpatients | Parallel, single centre |

| Overstall et al, 198733 | 4 | 62 | Lormetazepam 1 mg, chlormethiazole 384 mg, 7 nights | Mean age 80.7, inpatients | Parallel, single centre |

| Reeves, 197734 | 3 | 41 | Triazolam 0.25 mg, flurazepam 15 mg, 28 nights | Age range 63-78 (mean 68.6); outpatients | Parallel, single centre |

| Richards et al, 198835 | 4 | 145 | Lormetazepam 0.5 mg, 1 mg, 7 nights | Mean age 72.5; participant characteristics not reported | Parallel, multicentre |

| Roger et al, 199336 | 4 | 221 | Zolpidem 5 mg, 10 mg, triazolam 0.25 mg, 21 nights | Age range 58-98 (mean 81.1); inpatients | Parallel, multicentre |

| Roth et al, 199741 | 4 | 30 | Quazepam 7.5 mg, 15 mg, 7 nights | Mean age 65.9, outpatients | Parallel, single centre |

| Viukari et al, 198437 | 3 | 32 | Brotizolam 0.125 mg, nitrazepam 2.5 mg, 7 nights | Age range 62-98 (mean 81); residents in old people's home | Crossover, washout 7 nights, single centre |

Score out of 6, 1 for blinding+3 for method of randomisation and allocation concealment, 2 for follow-up (Jadad criteria).

Vesperax=hydroxyzine 50 mg, brallobarbital 50 mg, secobarbital 150 mg, not evaluated here.

Quality of sleep

Number needed to treat was derived from four studies that in which participants reported any improvement in sleep quality (considered “successes”) compared with no improvement or a worsening in sleep quality (“failures”). On the basis of four studies (1072 participants), the number of patients who would need to be treated with a sedative (zaleplon, brotizolam or nitrazepam, or loprazolam) for one to have an improvement in sleep quality is 13 (95% confidence interval 6.7 to 62.9).18,20,25,37

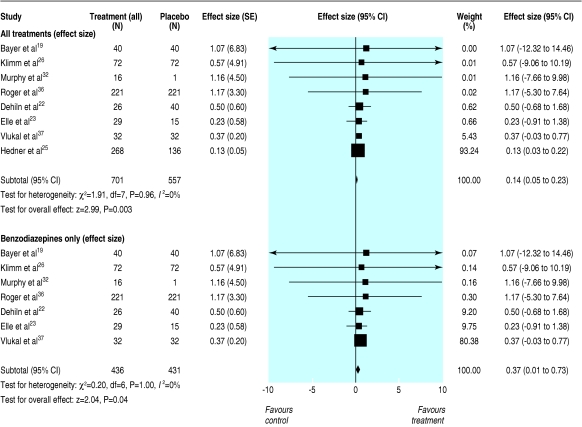

Eight studies (719 participants) had extractable sleep quality score data (means and standard deviations) for any sedative versus placebo, and we used these to determine the magnitude of effect.19,21,23,25,26,32,36,37 Reported sleep quality was significantly better with sedative use (mean effect size 0.14, 0.05 to 0.23; P < 0.005, fig 2). This effect size indicates a difference in mean scores on sleep quality for sedative versus placebo groups of 0.11. In the most heavily weighted study in the analysis,25 this would correspond to mean scores of 3.8 in the placebo group and 3.7 in the sedative group on a seven point scale.

Fig 2.

Mean effect size (95% confidence intervals) for subjective improvements in sleep quality with any sedative treatment and benzodiazepines only compared with placebo for at least five nights in people aged 60 or older with insomnia

Seven studies (277 participants) were combined to see the effect of benzodiazepines only versus placebo on sleep quality measures.19,21,23,26,32,36,37 A significant improvement in sleep quality improved significantly (mean effect size 0.37, 0.01 to 0.73; fig 2). This effect size corresponds to a difference of 0.46 between the treatment means—scores of 2.7 for placebo and 3.1 for drug, on the five point scale used by the most heavily weighted study in this analysis.37

Three studies (339 participants) comparing benzodiazepines with benzodiazepine receptor agonists (zaleplon, zolpidem, and zopiclone) found no significant difference in sleep quality (mean effect size 0.04, -1.11 to 1.19; test for heterogeneity P = 1.0).23,26,36

Two studies (116 participants) that reported sleep quality data for zopiclone versus placebo had a magnitude of effect of 0.41 (-0.76 to 1.58; test for heterogeneity P = 0.98).23,26 Data for zolpidem or zaleplon versus placebo were insufficient for inclusion.

Amount of sleep

In eight studies (601 participants) with extractable data, the increase in total sleep time with any sedatives compared with placebo was 25.2 minutes (12.8 to 37.8 minutes; P = 0.001; test for heterogeneity P = 0.10).20,21,27-29,31,34,37 In eight studies (524 participants) that compared benzodiazepines with placebo, the increase in total sleep time was 34.2 minutes (16.2 to 52.8 minutes, P < 0.01; test for heterogeneity P = 0.13).20,21,27-29,31,34,37

Data were insufficient to analyse sleep onset latency or ease of getting to sleep.

Number of awakenings

In six studies (441 participants) with extractable data, the mean number of awakenings decreased by 0.63 (-0.48 to -0.77, P < 0.0001; test for heterogeneity P = 0.71).20,22,27,29,34,36 In six studies with benzodiazepines versus placebo (296 participants) the mean number of awakenings decreased by 0.60 (-0.41 to -0.78, P < 0.0001; test for heterogeneity P = 0.58).20,22,27,29,34,36

Adverse events

On the basis of all adverse events reported in 16 studies (2220 participants), the number needed to harm for sedative hypnotics compared with placebo is 6 (4.7 to 7.1).18-28,30,34,37,39-41 The most common adverse events were drowsiness or fatigue, headache, nightmares, and nausea or gastrointestinal disturbances. As severity of adverse events was reported in only one study, pooled estimates could not be determined.

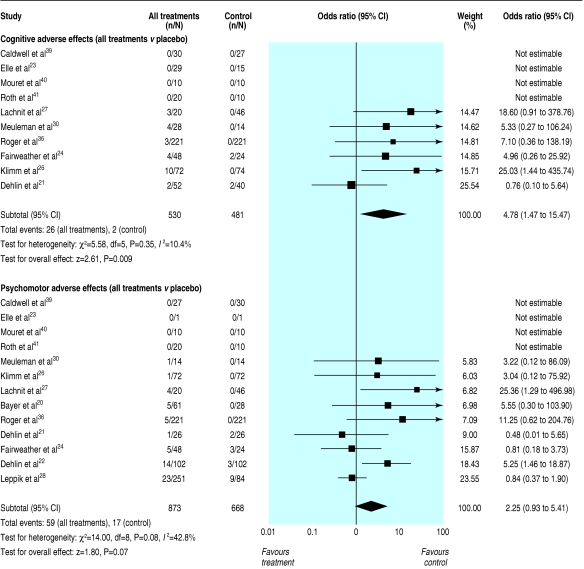

On the basis of 10 studies (712 participants), cognitive effects were significantly more common with sedative use than with placebo (odds ratio 4.78, 1.47 to 15.47, P < 0.01; test for heterogeneity P = 0.35, fig 3).21,23,24,26,27,30,36,39-41

Fig 3.

Cognitive and psychomotor adverse events, odds ratios, z scores, and test for heterogeneity for any sedative hypnotics taken for at least five nights in people aged 60 or older with insomnia

Psychomotor-type side effects such as reported dizziness or loss of balance were reported in 13 studies (1016 participants) and were more common after treatment with a sedative, but this result did not reach significance (odds ratio 2.25, 0.93 to 5.41, P = 0.07; test for heterogeneity P = 0.08, fig 3).20-24,26-28,30,36,39-41 Of the 59 psychomotor effects that were reported, seven were serious events (six falls and one motor vehicle crash). Three resulted in broken bones: a fall resulting in a broken hip after five nights of 15 mg temazepam,30 a fall resulting in a broken femur after 0.125 mg triazolam,38 and one case of hip fracture while taking placebo.28 A motor vehicle crash after a single dose of temazepam 15 mg was reported.28

There were significantly more subjective reports of morning or daytime fatigue (seven studies, 829 participants) after treatment than after placebo (odds ratio 3.82, 1.88 to 7.80, P < 0.001).20,21,26,28,30,36,38

Impairment on performance tasks the morning after sedative use (four studies, 251 participants) was significantly greater than after placebo (d = 0.14, 0.11 to 0.16; test for heterogeneity P = 0.57).20,21,24,29

Six studies (648 participants) that compared benzodiazepine receptor agonists and benzodiazepine reported little difference in numbers of adverse events (odds ratio 1.11, 0.59 to 2.07, P = 0.75; test for heterogeneity P = 0.07).22,23,26,28,36,40 Studies of zaleplon, zopiclone and zolpidem (combined) versus benzodiazepines found no significant difference in cognitive adverse events (four studies, 268 participants; odds ratio 1.12, 0.16 to 7.76, P = 0.91; test for heterogeneity P = 0.35)23,26,36,40 or psychomotor-type adverse events (six studies, 625 participants; odds ratio 1.48, 0.75 to 2.93; test for heterogeneity P = 0.46).22,23,26,28,36,40

Publication bias

Funnel plot analyses indicated a possible publication bias on outcomes of sleep quality and total sleep time favouring positive results (rs = 0.78, P ≤ 0.05). The mean effect size did not change after “trim and fill” to correct estimates of effect size, and the result was still significant in favour of sedatives (d = 0.14, P ≤ 0.05 for sleep quality; mean increase in total sleep time = 15 minutes, P ≤ 0.05).

Discussion

Treatment with sedative hypnotics improves the quality of sleep, evaluated subjectively. The effect size (0.14) is small according to the classification by Cohen (in which a small effect size is about 0.2).42 Sleep quality is a measure of efficacy for sleep medications and also a measure of patient satisfaction. Findings for both total sleep time and number of night time awakenings showed significant although small improvements in patients who took a sedative rather than placebo.

Risk of adverse events

The risk of adverse events was higher with sedative treatment. Most adverse events were reported to be reversible and not severe.18,20-28,34,37,39,41 Patients who took sedatives had a higher incidence of falls and motor vehicle crashes.

Numbers needed to treat versus numbers needed to harm

The number needed to treat for improved sleep quality was 13 and the number needed to harm for any adverse event was 6. This ratio indicates that an adverse event is more than twice as likely as enhanced quality of sleep. This ratio can be used as a rough indicator only, as more than double the number of participants contributed to the “harm” data than to the “effectiveness” data (2220 v 1072). The effectiveness estimate is less precise (the confidence interval is wider).

Comparison with the literature

Although meta-analyses have examined the effects of benzodiazepines and the new benzodiazepine-receptor agonists, they have not examined their effects in older people. Nowell et al combined five studies that included people under 65 with insomnia and found a positive effect size of 0.62 (0.45 to 0.79) for benzodiazepines and zolpidem versus placebo for sleep quality scores.43 Smith et al found an effect size of 1.2 when pharmacotherapy was compared with placebo in their meta-analysis of studies including both younger and older adults, using effect size that was weighted using studies' sample sizes.44 These studies describe greater overall effects of sedative on sleep quality than we found. Although our results for sleep quality were heavily weighted by one study that had a large sample size (n = 404) and small standard error,25 removing this study from the analysis resulted in a mean effect size that was still lower than those reported by previous meta-analyses (d = 0.37).

Similarly, in a meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in adults with insomnia, Holbrook et al found a significant increase in total sleep time of 48.4 minutes with benzodiazepine use.12 Smith et al reported a significant increase in total sleep time of 40.5 minutes with pharmacotherapy compared with placebo and a decrease in the number of awakenings experienced during the night (-1.17).44 These results are more positive than those in the present meta-analysis. This may indicate that sedative medications, particularly benzodiazepines, may benefit older patients less than younger adults. These differences may be due to differences in subjective reporting or in the studies that have been included as no direct comparisons have been made between younger and older adults.

Holbrook et al found a significant increase in adverse events with benzodiazepine use (odds ratio 1.8, 1.4 to 2.4). The increase in psychomotor-type side effects found with sedative use in our study (odds ratio 2.61) is similar to the increase in reports of dizziness and lightheadedness found in the Holbrook meta-analysis after benzodiazepine use (odds ratio 2.6, 0.7 to 10.3). Holbrook et al also report a significant increase in reports of daytime fatigue with benzodiazepine use (odds ratio 2.4, 1.8 to 3.4).12 This is lower than our reported odds ratio for subjective reports of daytime fatigue after night time sedative use (odds ratio 3.82). This may indicate that older people have similar or greater potential for risks such as adverse events than younger adults.

Loss of memory and confusion have been reported with older sedative hypnotics such as triazolam and newer sedatives such as zolpidem in patients of all ages.45,46 The risk for these events may be even higher in elderly patients. Although investigators in the studies we included stated that patients were not cognitively impaired, they did not always use validated scales such as the mini-mental state examination to support these claims. Any pre-existing cognitive impairment may exacerbate confusion or memory problems.47

An increased risk for adverse events is consistent with reported risks for falls and motor vehicle crashes or household incidents.48 Older people may be at greater risk for adverse effects because of pharmacokinetic considerations, such as reduced clearance of certain sedative hypnotics.49-51 There is also some evidence of pharmacodynamic differences such as increased sensitivity to peak drugs effects.51

We found that the impairment of performance tasks the morning after sedatives are used, though significant, is small. This may indicate that, even when fatigue is reported, reaction time or hand-eye coordination after sedative use does not deviate greatly from normal.

Epidemiological evidence shows an increased risk of car crashes in elderly people who are using long acting sedatives (nitrazepam or flurazepam, for example) but not with short acting sedatives (such as triazolam or temazepam).52 Impairment depends on dose and time since dosing.53 The small effects of morning after impairment that we found may be due to the heterogeneous half lives and doses of the drugs tested, as well as the variable times of testing after dosing.

Limitations of this study

Interpretation of this meta-analysis must take into account that all sedatives or all benzodiazepines were grouped together for analyses, irrespective of differences in half life, potency, or dosage. As well, no standard method of collecting subjective sleep variables is available. The studies used various measures: ordinal scales (three, five, or seven point), visual analogue scales, and combined scales. Though subjective reports create more variable results than objective measures, we focused on subjective ratings of sleep variables as the primary outcome measure because consumption of healthcare resources is driven by subjective report rather than objective measures of sleep.

Another potential source of variability was the health status of the participants in the studies. Some were community dwelling ambulatory patients attending a health clinic and others were inpatients on a geriatric ward. Differences in environment or health status may affect how people respond to subjective assessments. Furthermore, although studies were double blind, the psychotropic effects of sedative hypnotics may be cues that compromise blinding, which may in turn affect subjective reports.

In some cases, such as when studies did not have placebo arms, placebo run-in scores were used as control scores (see table). Sleep has improved over time during clinical studies with self monitoring and recording patterns, and after tips for improving sleep hygiene have been given.43,54 Two studies excluded placebo responders, leading to an enriched sample.18,19 Using placebo run-in scores or enriched samples might lead to underestimated placebo effects and inflated estimates of treatment effects.

Dependence and habituation are some of the major concerns with sedative use, but were not addressed directly in any of the studies. These factors also weigh on the risk-benefit relation, but their role could not be determined in this study.

What is already known on this topic

Benzodiazepines and newer benzodiazepine receptor agonists are thought to be efficacious for sleep disturbances in elderly people

They are associated with risks that are particularly detrimental in elderly people, such as ataxia, cognitive effects, and falls

Little is known about how the risks and benefits compare for non-prescription sedative hypnotics

What this study adds

In people over 60, the benefits associated with sedative use are marginal and are outweighed by the risks, particularly if patients are at high risk for falls or cognitive impairment

Conclusions

Although the improvements in sleep variables obtained from prescription sedative hypnotics are statistically significant, the effect size is small, and the clinical benefits may be modest at best. The added risk of an adverse event may not justify these benefits, particularly in a high risk elderly population. These factors should be considered when sedative hypnotics are prescribed for older patients. Non-pharmacological therapies such as cognitive behaviour therapy have been shown to be as efficacious as pharmacotherapy for insomnia in older people.44,55 Because fewer risks are associated with behavioural therapies,31,44,56 they may be a viable treatment alternative in a healthy elderly population with no cognitive impairment.

Supplementary Material

Contributors: JG wrote the protocol with input from all authors, did the initial searches and study selection, data abstraction, and data analyses including graphics, and wrote the paper. She is guarantor. UEB helped write the protocol and establish the inclusion and exclusion criteria, evaluated study quality, carried out data abstraction, and edited the final manuscript. KLL helped write the protocol, assisted and reviewed data analyses and statistical analyses, graphing, and interpretation of results, and edited the final report. NH helped write the protocol, gave clinical input into the study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, evaluated study quality, and edited the final manuscript. BAS provided input on the protocol, including clinical input, commented on interim results, and reviewed and edited results (including graphs and tables) and the final manuscript.

Funding: None. This study was part of a PhD thesis for JG.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

References

- 1.Brostrom A, Stromberg A, Dahlstrom U, Fridlund B. Sleep difficulties, daytime sleepiness, and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2004;19: 234-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byles JE, Mishra GD, Harris MA, Nair K. The problems of sleep for older women: changes in health outcomes. Age Ageing 2003;32: 154-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev 2002;6: 97-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holbrook AM, Crowther R, Lotter A, Cheng C, King D. The diagnosis and management of insomnia in clinical practice: a practical evidence-based approach. CMAJ 2000;162: 206-10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aparasu RR, Mort JR, Brandt H. Psychotropic prescription use by community-dwelling elderly in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51: 671-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig D, Passmore AP, Fullerton KJ, Beringer TR, Gilmore DH, Crawford VL, et al. Factors influencing prescription of CNS medications in different elderly populations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2003;12: 383-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbone F, McMahon AD, Davey PG, Morris AD, Reid IC, McDevitt DG, et al. Association of road-traffic accidents with benzodiazepine use. Lancet 1998;352: 1331-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neutel CI, Perry S, Maxwell C. Medication use and risk of falls. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2002;11: 97-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12: 189-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleming JAE. Insomnia. In: Gray J, ed. Therapeutic choices. Ottawa: Canadian Pharmacists Association, 2003: 54-62.

- 11.Jadad A, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17: 1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holbrook A, Crowther R, Lotter A, Cheng C, King D. Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of insomnia. CMAJ 2000;162: 225-33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McAlister FA, Straus SE, Guyatt GH, Haynes RB. Users' guides to the medical literature. XX. Integrating research evidence with the care of the individual patient. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 2000;283: 2829-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Craen AJ, Vickers AJ, Tijssen JG, Kleijnen J. Number-needed-to-treat and placebo-controlled trials. Lancet 1998;351: 310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50: 1088-101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cochrane collaboration open learning material. Module 15. 2002. www-cochrane-net.org/openlearning/HTML/mod15/htm (accessed Mar 2004).

- 17.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000;56: 455-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ancoli-Israel S, Walsh JK, Mangano RM, Fujimori M. Zaleplon A. Novel nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic, effectively treats insomnia in elderly patients without causing rebound effects. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 1999;1: 114-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bayer AJ, Pathy MS, Ankier SI. An evaluation of the short-term hypnotic efficacy of loprazolam in comparison with nitrazepam in elderly patients. Pharmatherapeutica 1983;3: 468-74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayer A, Pathy MSJ. Clinical and psychometric evaluation of 2 doses of loprazolam and placebo in geriatric patients. Curr Med Res Opinion 1986;10: 17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dehlin O, Bjornson J. Triazolam as a hypnotic for geriatric patients. Act Psychiatr Scand 1983;67: 290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dehlin O, Rubin B, Rundgren A. Double-blind comparison of zopiclone and flunitrazepam in elderly insomniacs with special focus on residual effects. Curr Med Res Opinion 1995;13: 317-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elie R, Frenay M, Le Morvan P, Bourgouin J. Efficacy and safety of zopiclone and triazolam in the treatment of geriatric insomniacs. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1990;5(suppl 2): 39-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fairweather DB, Kerr JS, Hindmarch I. The effects of acute and repeated doses of zolpidem on subjective sleep, psychomotor performance and cognitive function in elderly volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1992;43: 597-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedner J, Yaeche R, Emilien G, Farr I, Salinas E. Zaleplon shortens subjective sleep latency and improves subjective sleep quality in elderly patients with insomnia. The Zaleplon Clinical Investigator Study Group. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000;15: 704-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klimm H, Dreyfus JF, Delmotte M. Zopiclone vs. nitrazepam: a double-blind comparative study of efficacy and tolerance in elderly patients with chronic insomnia. Sleep 1987;10: 73-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lachnit K, Proszolowski E, Rieder L. Midazolam in the treatment of sleep disorders in geriatric patients. Br J Clin Pharmac 1983;16 (suppl): 173-7S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leppik I, Roth-Schecheter GB, Gray GW, Cohn MA, Owens D. Double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of zolpidem, triazolam, and temazepam in elderly patients with insomnia. Drug Dev Res 1997;40: 230-8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mamelak M, Csima A, Buck L, Price V. A comparative study on the effects of brotizolam and flurazepam on sleep and performance in the elderly. J Clin Psychopharm 1989;9: 260-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meuleman JR, Nelson RC, Clark RL Jr. Evaluation of temazepam and diphenhydramine as hypnotics in a nursing-home population. Drug Intell Clin Pharm 1987;21: 716-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morin C, Colecchi C, Stone J, Sood R, Brink D. Behavioural and pharmacological therapies for late-life insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1999;281: 991-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy P, Hindmarch I, Hyland CM. Aspects of short-term use of two benzodiazepine hypnotics in the elderly. Age Ageing 1982;11: 222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Overstall P, Oldman PN. A comparative study of lormetazepam and chlormethiazole in elderly in-patients. Age Ageing 1987;16: 45-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reeves R. Comparison of triazolam, flurazepam, and placebo as hypnotics in geriatric patients with insomnia. J Clin Pharmacol 1977;17: 319-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richards HH, Valle-Jones CJ. A double-blind comparison of two lormetazepam doses in elderly insomniacs. Curr Med Res Opin 1988;11: 48-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roger M, Attali R, Coquelin JP. Multicentre, double-blind, controlled comparison of zolpidem and triazolam in elderly patients with insomnia. Clin Therapeutics 1993;15: 127-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viukari M, Vartio T, Verho E. Low doses of brotizolam and nitrazepam as hypnotics in the elderly. Neuropsychobiol 1984;12: 130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bayer A, Bayer EM, Pathy MSJ, Stoker MJ. A double-blind controlled study of chlomethiazole and triazolam as hypnotics in the elderly. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1986;73: 104-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caldwell JR. Short-term quazepam treatment of insomnia in geriatric patients. Pharmatherapeutica 1982;3: 278-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mouret J, Ruel D, Maillard F, Bianchi M. Zopiclone versus triazolam in insomniac geriatric patients: a specific increase in delta sleep with zopiclone. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1990;5(suppl 2): 47-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roth T, Roehrs TA, Ksohorek GL, Greenblatt DJ, Rosenthal LD. Hypnotic effects of low doses of quazepam in older insomniacs. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997;17: 401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Earlbaum, 1988.

- 43.Nowell PM, Mazumdar S, Buysse DJ, Dew MA, Reynolds CF 3rd, Kupfer DJ. Benzodiazepines and zolpidem for chronic insomnia: a meta-analysis of treatment efficacy. JAMA 1997;278: 2170-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith MT, Perlis ML, Park A, Smith MS, Pennington J, Giles DE, et al. Comparative meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy for persistent insomnia. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159: 5-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wysowski D, Barash D. Adverse behavioural reactions attibuted to triazolam in the Food and Drug Administration's spontaneous reporting system. Arch Intern Med 1991;151: 3003-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.American Sleep Disorders Association. International classification of sleep disorders diagnostics and coding manual. Rochester, MN: ASDA, 1990.

- 47.Mort JR, Aparasu RR. Prescribing of psychotropics in the elderly: why is it so often inappropriate? CNS Drugs 2002;16: 99-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kallin K, Jensen J, Olsson LL, Nyberg L, Gustafson Y. Why the elderly fall in residential care facilities, and suggested remedies. J Fam Pract 2004;53: 41-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greenblatt D, Harmatz JS, Shapiro L, Engelhardt N, Gouthro TA, Shader RI. Sensitivity to triazolam in the elderly. N Engl J Med 1991;324: 1691-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Greenblatt D, Shader RI, Harmatz JS. Implications of altered drug disposition in the elderly: studies of benzodiazepines. J Clin Pharmacol 1989;29: 866-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greenblatt DJ, Harmatz JS, von Moltke LL, Wright CE, Shader RI. Age and gender effects on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of triazolam, a cytochrome P450 3A substrate. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2004;76: 467-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hemmelgarn B, Suissa S, Huang A, Boivin J, Pinard G. Benzodiazepine use and the risk of motor vehicle crash in the elderly. JAMA 1997;278: 27-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ray W. Safety and mobility of the older driver. JAMA 1997;278: 66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kripke DF, Hauri P, Ancoli-Israel S, Roth T. Sleep evaluation in chronic insomniacs during 14-day use of flurazepam and midazolam. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1990;10(suppl): 32-43S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morin C, Culbert JP, Schwartz SM. Nonpharmacological interventions for insomnia: a meta-analysis of treatement efficacy. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151: 1172-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murtagh D, Greenwood KM. Identifying effective psychological treatments for insomnia: a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63: 79-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.