Abstract

Objectives To assess gestational length and prevalence of preterm birth among medically and naturally conceived twins; to establish the role of zygosity and chorionicity in assessing gestational length in twins born after subfertility treatment.

Design Population based cohort study.

Setting Collaborative network of 19 maternity facilities in East Flanders, Belgium (East Flanders prospective twin survey).

Participants 4368 twin pairs born between 1976 and 2002, including 2915 spontaneous twin pairs, 710 twin pairs born after ovarian stimulation, and 743 twin pairs born after in vitro fertilisation or intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

Main outcome measures Gestational length and prevalence of preterm birth.

Results Compared with naturally conceived twins, twins resulting from subfertility treatment had on average a slightly decreased gestational age at birth (mean difference 4.0 days, 95% confidence interval 2.7 to 5.2), corresponding to an odds ratio of 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8) for preterm birth, albeit confined to mild preterm birth (34-36 weeks). The adjusted odds ratios of preterm birth after subfertility treatment were 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) when controlled for birth year, maternal age, and parity and 1.6 (1.3 to 1.8) with additional control for fetal sex, caesarean section, zygosity, and chorionicity. Although an increased risk of preterm birth was therefore seen among twins resulting from subfertility treatment, the risk was largely caused by a first birth effect among subfertile couples; conversely, the risk of prematurity was substantially levelled off by the protective effect of dizygotic twinning.

Conclusions Twins resulting from subfertility treatment have an increased risk of preterm birth, but the risk is limited to mild preterm birth, primarily by virtue of dizygotic twinning.

Introduction

One in six couples attempting pregnancy fail to conceive naturally after 12 months of regular unprotected intercourse. Most of these couples eventually succeed, about half of them through subfertility treatment.1 Efforts to increase the success rates of subfertility treatment have been accompanied by an insidious rise in the rate of multifetal pregnancies.2 About half of medically conceived babies in the United States and Europe are now born as twins,3,4 and almost half of all twins result from subfertility treatment.2

In the face of this “multiple birth epidemic,” and despite widespread concern about the effects of medically aided conception on perinatal outcome, few studies have investigated outcomes in twins,5 and largely conflicting results have been reported.6 Fuller and more consistent data are needed to assess the impact of ovarian stimulation and assisted reproduction on pregnancy outcome.5

Twins tend to fare considerably worse than singletons, with much higher rates of perinatal mortality, neonatal morbidity, and long term neurological impairment.2 Adverse pregnancy outcome in turn relates to the high prevalence of preterm birth among twins and is exacerbated by monozygotic and monochorionic twinning.7-9 Whether subfertility treatment also impinges on gestational length in twins, as has been established among singletons,6,10 is unclear, as is the extent to which type of twinning interferes with perinatal outcome after subfertility treatment.11

In a population based cohort we compared gestational length and preterm birth rates between naturally and medically conceived twins. We also assessed the role of zygosity and chorionicity.

Methods

Study population

Multiple births in the East Flanders province of Belgium are recorded by the East Flanders prospective twin survey, through a collaborative network of 19 maternity units.8,9

Data collection

Methods of data collection have previously been described in detail.8,9 Briefly, for every multiple birth, a defined set of obstetric and perinatal data were recorded and placentas were collected and examined within 48 hours of delivery according to a standardised protocol. Zygosity and chorionicity were determined through sequential analysis of fetal sex, fetal membranes, and umbilical cord blood groups and by DNA fingerprinting based on allelic similarity within a twin pair of short tandem repeat loci on nine different chromosomes. Overall, zygosity and chorionicity were determined with an accuracy of over 99%.8,9

We estimated gestational length in number of days, principally on the basis of routine gestational dating combining last menstrual period and real time ultrasonography in early pregnancy, throughout the study period. In Flanders, more than 98% of women attend early in pregnancy and gestational dating is routinely confirmed or adjusted through ultrasound examination.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All twins with one of the children weighing at least 500 g were registered. From 1 January 1976 to 31 December 2002, 4989 twin pairs were recorded by the survey. We excluded 621 twin gestations from all analyses because data could not be ascertained for mode of conception (n = 53), maternal age (86), parity (52), gestational length (376), zygosity (69), birth weight (19 and 23), or infant sex (2 and 3).

Definitions

We defined preterm birth as birth at less than 37 completed weeks of gestation and low birth weight as weight at birth of less than 2500 g. The ovarian stimulation group included all women who conceived in vivo after any treatment regimen involving direct or indirect stimulation of ovulation, including regulation of the menstrual cycle, artificial induction of ovulation, or ovarian hyperstimulation without a subsequent in vitro procedure. The in vitro fertilisation/intracytoplasmic sperm injection group included all women who conceived (mostly after ovarian stimulation) through an in vitro procedure, generally referred to as assisted reproduction technology. The ovarian stimulation and in vitro fertilisation/intracytoplasmic sperm injection groups together comprise the subfertility group.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures were gestational length and rates of preterm birth according to mode of conception.

Statistical analyses

We first compared mean differences in continuous variables by using independent samples t tests and differences in prevalence rates by using χ2 tests with the Yates correction. We subsequently assessed differences in mean values and prevalence rates by fitting linear, marginal logistic, and ordinary logistic regression models. In a first set of models, we accounted for the pretreatment variables birth year, parity, and maternal age. Provided these were the only predictors associated with subfertility treatment, the resulting differences and odds ratios express the “overall effect” on the outcomes assessed. In a second set of models, we additionally removed the mediating effects of the post-treatment variables zygosity, chorionicity, intra-twin fetal sex combination, and caesarean section. Provided that no confounding variables remained that impinged on the intermediates or on the decision to apply subfertility treatment, the resulting differences and odds ratios express the “direct effect” of subfertility treatment. We corrected all analyses of birth weight for intra-twin correlation through generalised estimating equations with exchangeable working correlation.12

We used Lagrange multiplier tests for model comparisons. We used the conventional 5% level to assess significance. Analyses were done with SPSS version 12.0 and SAS version 8.02 statistical software.

Results

Study population

The population based cohort (n = 4368) comprised 2915 (66.7%) naturally conceived and 1453 (33.3%) medically conceived twin pairs, including 710 (16.3%) twin pairs born after ovarian stimulation and 743 (17.0%) twin pairs born after in vitro fertilisation or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (table 1). Women who had had subfertility treatment were on average older (P < 0.001) and less likely to have had a child previously (P < 0.001) than mothers in the natural conception group.

Table 1.

Maternal and perinatal characteristics of the study population. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

|

Natural conception group (n=2915)

|

Ovarian stimulation group (n=710)

|

IVF/ICSI group (n=743)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Value | P value | Value | P value | |

| Mean (SD) maternal age (years) | 28.6 (4.5) | 28.7 (3.7) | 0.08 | 31.5 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| Parity: | |||||

| 0

|

1309 (44.9)

|

437 (61.5)

|

<0.001 | 509 (68.5)

|

<0.001 |

| 1

|

977 (33.5)

|

216 (30.4)

|

200 (26.9)

|

||

| ≥2 | 629 (21.6) | 57 (8.0) | 34 (4.6) | ||

| Delivery mode: | |||||

| Caesarean

|

752 (25.8)

|

242 (34.1)

|

<0.001 | 315 (42.4)

|

<0.001 |

| Vaginal | 2163 (74.2) | 468 (65.9) | 428 (57.6) | ||

| Mean (SD) gestational age (days) | 257 (20) | 254 (19) | <0.001 | 252 (19) | <0.001 |

| Gestational age <37 weeks | 1314 (45.1) | 385 (54.2) | <0.001 | 441 (59.4) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SD) birth weight* (g) | 2440 (570) | 2390 (560) | 0.02 | 2375 (570) | 0.002 |

| Birth weight <2500 g† | 1803 (61.9) | 476 (67.0) | 0.009 | 515 (69.3) | <0.001 |

ICSI=intracytoplasmic sperm injection; IVF=in vitro fertilisation.

Mean birth weight within groups calculated from mean birth weights of twin pairs constituting each group.

Defined as at least one infant with birth weight below 2500 g.

The dizygotic:monozygotic twinning ratio was 95.2:4.8 among medically conceived twins and 53.8:46.2 in the natural conception group (P < 0.001) (table 2). The distribution of the intra-twin fetal sex combination differed significantly (P < 0.001) between naturally and medically conceived twins owing to differential zygosity, whereas the overall fetal sex distribution did not (P = 0.9).

Table 2.

Type of twinning according to mode of conception. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Natural conception group (n=2915) | Subfertility treatment group (n=1453) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monozygotic: | 1347 (46.2) | 70 (4.8) | <0.001 |

| Monochorionic | 885 (65.7) | 56 (80.0) | |

| Dichorionic | 462 (34.3) | 14 (20.0) | |

| Dizygotic: | 1568 (53.8) | 1383 (95.2) | <0.001 |

| Unlike sex* | 776 (49.5) | 688 (49.7) | 0.9 |

| Same sex, male | 410 (26.1) | 351 (25.4) | |

| Same sex, female | 382 (24.4) | 344 (24.9) |

Male-female or female-male twin pairs regardless of birth order.

Differences in gestational length and risk of preterm birth

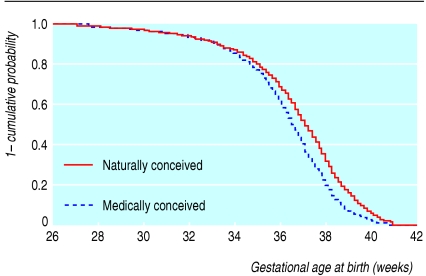

Subfertility treatment was associated with a small decrease in gestational age at birth compared with the natural conception group (tables 1 and 3; figure). This difference translated to an odds ratio of 1.6 (95% confidence interval 1.4 to 1.8) for preterm birth (table 4), albeit confined to mild preterm birth (≥ 34 weeks) (figure). Medically conceived twins were more likely to be preterm delivered by caesarean section (odds ratio 1.5, 1.2 to 1.9) but were also at higher risk of spontaneous preterm birth (odds ratio 1.6, 1.4 to 1.8). In agreement with the above, medically conceived twins had, on average, a slightly lower birth weight (table 1) and a slightly higher risk of low birth weight (odds ratio 1.2, 1.1 to 1.4) (table 5).

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted mean differences in gestational length between ovarian stimulation and IVF/ICSI groups of women, compared with natural conception group. Values are means (95% confidence intervals) unless stated otherwise

|

Observed effect

|

Overall effect*

|

Direct effect†

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Difference (days) | P value | Difference (days) | P value | Difference (days) | P value |

| Natural conception (n=2915) | Reference | - | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Ovarian stimulation (n=710) | 3.2 (1.6 to 4.9) | <0.001 | 1.9 (0.3 to 3.6) | 0.02 | 3.4 (1.7 to 5.2) | <0.001 |

| IVF/ICSI (n=743) | 4.6 (3.0 to 6.2) | <0.001 | 2.3 (0.5 to 4.1) | 0.01 | 3.9 (2.0 to 5.8) | <0.001 |

| Subfertility treatment‡ (n=1453) | 4.0 (2.7 to 5.2) | <0.001 | 2.1 (0.7 to 3.5) | 0.003 | 3.6 (2.2 to 5.1) | <0.001 |

ICSI=intracytoplasmic sperm injection; IVF=in vitro fertilisation.

Multivariable analysis accounting for birth year, maternal age, and parity (confounders).

Multivariable analysis accounting for birth year, maternal age, and parity (confounders) and for infant sex, caesarean delivery, zygosity, and chorionicity (mediating variables).

Comprises ovarian stimulation and IVF/ICSI groups.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier plot of gestational length in naturally conceived (n=2915) and medically conceived (n=1453) twins

Table 4.

Crude and adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) of preterm birth in ovarian stimulation and IVF/ICSI groups of women, compared with natural conception group

|

Observed effect

|

Overall effect*

|

Direct effect†

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Odds ratio | P value | Odds ratio | P value | Odds ratio | P value |

| Natural conception (n=2915) | Reference | - | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Ovarian stimulation (n=710) | 1.44 (1.22 to 1.70) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.07 to 1.50) | 0.007 | 1.42 (1.18 to 1.70) | <0.001 |

| IVF/ICSI (n=743) | 1.78 (1.51 to 2.10) | <0.001 | 1.38 (1.15 to 1.66) | <0.001 | 1.58 (1.30 to 1.92) | <0.001 |

| Subfertility treatment‡ (n=1453) | 1.61 (1.41 to 1.82) | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.14 to 1.51) | <0.001 | 1.49 (1.27 to 1.73) | <0.001 |

ICSI=intracytoplasmic sperm injection; IVF=in vitro fertilisation.

Multivariable analysis accounting for birth year, maternal age, and parity (confounders).

Multivariable analysis accounting for birth year, maternal age, and parity (confounders) and for infant sex, caesarean delivery, zygosity, and chorionicity (mediating variables).

Comprises ovarian stimulation and IVF/ICSI groups.

Table 5.

Crude and adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) of low birth weight in ovarian stimulation and IVF/ICSI groups of women, compared with natural conception group

|

Observed effect

|

Overall effect*

|

Direct effect†

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Odds ratio | P value | Odds ratio | P value | Odds ratio | P value |

| Natural conception (n=2915) | Reference | - | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Ovarian stimulation (n=710) | 1.20 (1.04 to 1.38) | 0.01 | 1.07 (0.93 to 1.24) | 0.4 | 1.26 (1.08 to 1.50) | 0.002 |

| IVF/ICSI (n=743) | 1.26 (1.10 to 1.45) | <0.001 | 1.09 (0.93 to 1.28) | 0.3 | 1.28 (1.09 to 1.47) | 0.004 |

| Subfertility treatment‡ (n=1453) | 1.23 (1.10 to 1.37) | <0.001 | 1.08 (0.96 to 1.22) | 0.2 | 1.27 (1.11 to 1.45) | <0.001 |

ICSI=intracytoplasmic sperm injection; IVF=in vitro fertilisation.

Multivariable analysis accounting for birth year, maternal age, and parity (confounders).

Multivariable analysis accounting for birth year, maternal age, and parity (confounders) and for infant sex, caesarean delivery, zygosity, and chorionicity (mediating variables).

Comprises ovarian stimulation and IVF/ICSI groups.

Adjusted differences in gestational length and risk of preterm birth

We estimated the overall effect of subfertility treatment by adjusting the outcomes for birth year, maternal age, and parity. The observed differences in gestational length (table 3) and rates of preterm birth (table 4) were clearly attenuated when we accounted for confounding; lower parity among women who conceived medically was the strongest confounder. The observed effects were, however, not entirely explained by these confounding effects. Assuming that no residual confounders remained, a minor but significant overall effect of subfertility treatment on gestational length could therefore not be ruled out on the basis of the observed data (tables 3 and 4), although this was not obvious from differences in birth weight (table 5).

To assess the direct effect of subfertility treatment, we additionally accounted for zygosity, chorionicity, fetal sex, and delivery mode (caesarean versus vaginal), which act on the pathway from conception to birth as intermediate variables to the outcomes assessed. When we accounted for this defined set of confounders and intermediates, the markedly higher effect size of the direct effect on gestational length (table 3) and preterm birth (table 4) over and above the overall effect was mainly attributable to the effect of zygosity. Chorionicity had a marginal effect on gestational length beyond zygosity, and caesarean delivery showed no effect at all after confounding was accounted for. According to our analyses, dizygotic twinning pertaining to iatrogenic pregnancy therefore proves a strong and advantageous mediator of gestational length (table 4), as is also apparent from the data on birth weight (table 5).

Discussion

Twins resulting from in vivo conception after ovarian stimulation or from in vitro conception with assisted reproduction technologies have on average a slightly decreased gestational age at birth and, accordingly, incur an increased risk of mild preterm birth compared with naturally conceived twins. According to our analyses, this is largely explained by a first birth effect among the subfertility groups of women; conversely, gestational length substantially benefits from predominantly dizygotic twinning after subfertility treatment.

Limitations of the study

The main shortcoming of this study is the lack of data on potential confounding by socioeconomic status. Despite liberal access to subfertility treatment in Belgium, including partial reimbursement, we cannot be sure that women of higher social classes were not over-represented in the subfertility group. If anything, such bias probably led to an underestimation of the effects attributed to subfertility treatment.

Overall, as in all observational studies, inferences in this study rely on a defined set of confounders. Our findings must be interpreted with caution, as we cannot be certain that residual confounders have not been accounted for.

We should further acknowledge that the study design is imperfect, to the extent that no inferences can be made on subfertility treatment as such, because we compared subfertile couples with naturally conceiving couples, and the former were thus exposed to both subfertility and treatment for subfertility. Similarly, as the ovarian stimulation and in vitro fertilisation/intracytoplasmic sperm injection groups of women probably differed in many respects, including cause of subfertility, no comparisons can be made between these in terms of subfertility treatment alone.

Finally, although gestational dating was undoubtedly prone to random inaccuracy, we have no reason to assume that systematic errors in gestational length assessment biased our results. This contention is further supported by the congruence between reported measures of gestational length and birth weight.

Strengths of the study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first population based twin study in which subfertility treatment per se, rather than (in vitro) assisted reproductive technologies alone, made up the exposure variable. Similarly, no previous study properly accounted for the role of zygosity and chorionicity in assessing perinatal outcomes after subfertility treatment through systematic determination of twinning type.

Subfertility treatment as a risk factor for preterm birth

The fact that subfertility has been consistently associated with adverse perinatal outcome in singleton gestation, although less so in twin gestations,6 challenges the prevailing paradigm that subfertile patients per se incur an increased obstetric risk.13 As a putative explanation, most medically aided pregnancies actually result from multiple conception, so those that continue as twin pregnancies may start off with a relative advantage.6,14 Although this is plausible, it is probably as much true for natural twin pregnancies, considering that only one in eight fetuses originating as a twin actually goes on to be born as a twin.15

It has further been postulated that predominantly dizygotic or dichorionic twinning also gives medically conceived twins an advantage, although this is not apparent from previous studies.6 Dizygotic twinning did prove an important protective feature pertaining to ovarian stimulation and assisted reproduction in our study.

Magnitude of the risk

Among singletons resulting from assisted reproduction, two recent meta-analyses showed a 5.3-6.2% excess rate of preterm birth (from 6.1% to 11.4%6 and from 5.3% to 11.5%10), corresponding to an odds ratio of 2.0. The odds ratios in our study were strikingly lower, but this contention should not be misconstrued,16 considering the 10-fold higher prevalence of preterm birth among twins compared with singletons. In particular, we observed an excess preterm birth rate of 11.7%, which is about twice the excess rate reported in singletons. The effects of subfertility treatment on preterm birth rates are therefore certainly not smaller than those among singletons. The effects on mean gestational length, and therefore on the degree or severity of prematurity, on the contrary are markedly less pronounced than in singletons,6 by virtue of dizygotic twinning after subfertility treatment.

Although it is reassuring that among twins the risk is confined to mild preterm birth, preterm delivery at any given gestational age is a more hazardous event to twins than it is to singletons.17 Overall, mild preterm birth still makes an important contribution to infant deaths.18

Comparison with other studies

We identified no similar population based studies in which gestational length in twins was rigorously compared according to fertility status or mode of conception. A recent authoritative review reiterated that the absence of registry based data on treatments involving ovarian stimulation without a subsequent in vitro procedure continues to hamper the study of multiple births resulting from subfertility treatment.19 Previous studies may therefore also be affected by substantial misclassification bias through allocating women who conceived after ovarian stimulation to the natural conception group, as has been acknowledged by Schieve et al in their nationwide US population based study.20 Similarly, in the large Danish population based cohort of twins, it was estimated that some 15-20% of women in the twin reference population actually conceived after induction of ovulation.7

Regarding the role of zygosity and chorionicity, we have previously documented that duration of pregnancy and birth weight is highest in dizygotic twins, lower in monozygotic dichorionic twins, and further impaired in monozygotic monochorionic twins.9 At least five previous studies attempted to partially control for zygosity by confining the analyses to twins of unlike sex,7,14,21-23 as an incomplete proxy for zygosity, which may explain why the effect of zygosity was not apparent.6 Recognition of zygosity and chorionicity is a labour intensive procedure involving examination of the placentas and DNA typing,15 so data on type of twinning are usually not available from birth or twin registries.

Conclusions and recommendations

From a public health perspective, subfertility treatment is associated with a certain degree of prematurity over and above the intrinsic preterm birth risk of multiplicity. This is important to the extent that an ever increasing number of babies result from subfertility treatment, half of these being twins, while on the whole twins contribute disproportionately to the prematurity related disease burden.

For scientific and clinical understanding on the other hand, it is equally important to recognise that gestational length after subfertility treatment tends to be largely determined by maternal characteristics, whereas primarily dizygotic twinning pertaining to subfertility treatment seems to be a strong and clinically advantageous feature of medically conceived twins.

We suggest that apposite consideration of altered zygosity distributions after subfertility treatment, as well as ascertainmentof mode of conception, is imperative to future research on perinatal outcome and infant health in twins. Finally, although huge efforts are now being made to counteract multifetal pregnancy rates through elective single embryo transfer, the multiple birth epidemic may continue as a result of the wide use of ovulation inducing agents.

What is already known on this topic

Half of all children resulting from subfertility treatment are born as twins; most of these are dizygotic

Unlike singletons, twins resulting from subfertility treatment are not deemed to have worse perinatal outcome than their naturally conceived counterparts

What this study adds

Twins conceived through artificial induction of ovulation with or without subsequent in vitro fertilisation had on average a slightly decreased gestational age at birth

This difference corresponded to a 60% increased odds of preterm birth after subfertility treatment compared with natural conception

The risk was confined to mild preterm birth at 34-36 weeks, primarily by virtue of dizygotic twinning with subfertility treatment

We thank all East Flemish maternity facilities and gynaecologists for their longstanding and continued support for the survey. We also thank midwives Lut De Zeure and Ingeborg Berckmoes for their excellent fieldwork and technical assistance.

Contributors: HV participated in the conception and design of the study, in the analysis and interpretation of the data, and in the drafting of the article. MT and EG participated in the conception and design of the study, in the interpretation of the data, and in providing critical revision for important intellectual content of the article. SG and SV participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data and in the drafting of the article. CD participated in the conception and design of the study, in the collection and interpretation of the data, and in providing critical revision for important intellectual content of the article. RD participated in the conception and design of the study and in providing critical revision for important intellectual content of the article. HV and SG made an equal overall contribution to the study. HV and MT are the guarantors.

Funding: From its inception, the East Flanders prospective twin survey has been partly supported by grants from the Fund of Scientific Research, Flanders, and by the Association for Scientific Research in Multiple Births (vzw Twins). This study was supported through grants from the Ghent University Research Fund (HV) and the Institute for the Promotion of Innovation through Science and Technology in Flanders (IWT-Vlaanderen) (SG). As the main funding sources, the Ghent University Research Fund and the Institute for the Promotion of Innovation through Science and Technology were not involved in designing the study, the conduct of the study, drafting the manuscript, or the decision to publish. SV is a postdoctoral research fellow of the Fund for Scientific Research, Flanders.EG is also adjunct associate professor, Department of Biostatistics, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Ghent University hospital ethical board approved the study protocol.

References

- 1.Taylor A. ABC of subfertility: extent of the problem. BMJ 2003;327: 434-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blondel B, Kaminski M. Trends in the occurrence, determinants, and consequences of multiple births. Semin Perinatol 2002;26: 239-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright VC, Schieve LA, Reynolds MA, Jeng G. Assisted reproductive technology surveillance—United States, 2000. MMWR Surveil 2003;52: 1-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nyboe Andersen A, Gianaroli L, Nygren KG, European IVF-monitoring programme, European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2000: results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod 2004;19: 490-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blondel B, Macfarlane A. Rising multiple maternity rates and medical management of subfertility: better information is needed. Eur J Public Health 2003;13: 83-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helmerhorst FM, Perquin DA, Donker D, Keirse MJ. Perinatal outcome of singletons and twins after assisted conception: a systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ 2004;328: 261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinborg A, Loft A, Rasmussen S, Schmidt L, Langhoff-Roos J, Greisen G, et al. Neonatal outcome in a Danish national cohort of 3438 IVF/ICSI and 10,362 non-IVF/ICSI twins born between 1995 and 2000. Hum Reprod 2004;19: 435-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derom C, Derom R. The East Flanders prospective twin survey. In: Blickstein I, Keith LG, eds. Multiple pregnancy: epidemiology, gestation and perinatal outcome. 2nd ed. Oxon: Taylor and Francis, 2005: 39-47.

- 9.Loos R, Derom C, Vlietinck R, Derom R. The East Flanders prospective twin survey (Belgium): a population-based register. Twin Res 1998;1: 167-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson RA, Gibson KA, Wu YW, Croughan MS. Perinatal outcomes in singletons following in vitro fertilization: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103: 551-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machin GA. Why is it important to diagnose chorionicity and how do we do it? Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2004;18: 515-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diggle PJ, Liang K, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. (Oxford Statistical Science series, No 13.)

- 13.Basso O, Baird DD. Infertility and preterm delivery, birth weight, and caesarean section: a study within the Danish national birth cohort. Hum Reprod 2003;18: 2478-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhont M, De Sutter P, Ruyssinck G, Martens G, Bekaert A. Perinatal outcome of pregnancies after assisted reproduction: a case-control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;181: 688-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall JG. Twinning. Lancet 2003;362: 735-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies HT, Crombie IK, Tavakoli M. When can odds ratios mislead? BMJ 1998;316: 989-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrett JF. Delivery of the term twin. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2004;18: 625-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer MS, Demissie K, Yang H, Platt RW, Sauve R, Liston R. The contribution of mild and moderate preterm birth to infant mortality. JAMA 2000;284: 843-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fauser BC, Devroey P, Macklon NS. Multiple birth resulting from ovarian stimulation for subfertility treatment. Lancet 2005;365: 1807-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schieve LA, Meikle SF, Ferre C, Peterson HB, Jeng G, Wilcox LS. Low and very low birth weight in infants conceived with use of assisted reproductive technology. N Engl J Med 2002;346: 731-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moise J, Laor A, Armon Y, Gur I, Gale R. The outcome of twin pregnancies after IVF. Hum Reprod 1998;13: 1702-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koudstaal J, Bruinse HW, Helmerhorst FM, Vermeiden JP, Willemsen WN, Visser GH. Obstetric outcome of twin pregnancies after in-vitro fertilization: a matched control study in four Dutch university hospitals. Hum Reprod 2000;15: 935-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lambalk CB, van Hooff M. Natural versus induced twinning and pregnancy outcome: a Dutch nationwide survey of primiparous dizygotic twin deliveries. Fertil Steril 2001;75: 731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]