Abstract

We have identified a Y-chromosomal lineage that is unusually frequent in northeastern China and Mongolia, in which a haplotype cluster defined by 15 Y short tandem repeats was carried by ∼3.3% of the males sampled from East Asia. The most recent common ancestor of this lineage lived 590 ± 340 years ago (mean ± SD), and it was detected in Mongolians and six Chinese minority populations. We suggest that the lineage was spread by Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) nobility, who were a privileged elite sharing patrilineal descent from Giocangga (died 1582), the grandfather of Manchu leader Nurhaci, and whose documented members formed ∼0.4% of the minority population by the end of the dynasty.

On a broad scale, patterns of human genetic variation reflect global events, such as the expansion out of Africa ∼50,000–70,000 years ago and Neolithic transitions <∼10,000 years ago, but sometimes they show substantial departures from these general trends because of local factors, such as drift in small populations or selection (Jobling et al. 2004). The Y chromosome is particularly sensitive to local events because of the reduced number of Y chromosomes in the population, compared with autosomes or X chromosomes, and because of the high variance in male reproductive success. Studies of Y-chromosomal variation are, therefore, well suited to detecting such effects and, indeed, reveal the effects of drift, both in populations known to have experienced it (e.g., Hedman et al. 2004) and in others (e.g., Zerjal et al. 2002). Y-chromosomal studies have also revealed evidence of selection, with one lineage now making up an estimated 0.5% of the world’s Y chromosomes, derived from a common ancestor ∼1,000 years ago and with a spread ascribed to the influence of Genghis Khan (Zerjal et al. 2003; Katoh et al. 2005). The importance of such social selection, however, remains to be established, and we have therefore examined Y-chromosomal data from East Asia for signs of further unusual lineages.

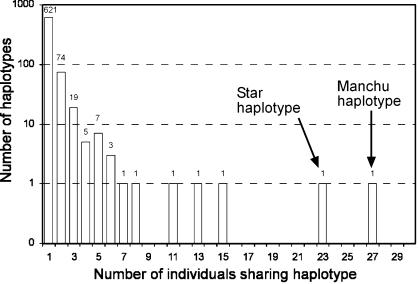

Previously, 1,003 males representing 28 populations from China, Mongolia, Korea, and Japan were typed with 16 Y STRs (Zerjal et al. 2003). The frequency distribution of 15-element haplotypes, constructed without DYS19 since duplications of this locus are common in this data set, shows that most haplotypes (621 [84%] of 736 ) are present in a single individual and that haplotypes shared by two or more individuals become progressively rarer, so that no haplotype is shared by nine individuals (fig. 1). Five haplotypes, however, fell outside this distribution pattern and were unexpectedly frequent in East Asian populations, having been found in 11, 13, 15, 23, and 27 individuals. The first three were found predominantly in a single population or two nearby populations and, thus, could have been spread by local drift in populations of small size. The other two, however, were more widespread. The haplotype present in 23 individuals was found in eight populations (and in more that are outside the area considered here) and is the “star cluster” described elsewhere (Zerjal et al. 2003). The most frequent haplotype in this sample, designated the “Manchu haplotype” for reasons described below, was present in 27 individuals belonging to seven populations. These two high-frequency haplotypes differ by only four steps, which raises the question of whether their prevalence might have a common cause. We show below, however, that they belong to different haplogroups and, thus, that their recent expansions must be independent. Here, we examine the distribution and likely origin of the second unusual haplotype.

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of Y-chromosomal haplotypes in East Asia. The two most frequent haplotypes identified by the 15 loci DYS388-DYS389I-DYS389b-DYS390-DYS391-DYS392-DYS393-DYS425-DYS426-DYS434-DYS435-DYS436-DYS437-DYS438-DYS439 are 14-10-16-25-10-11-13-12-11-11-11-12-8-10-10 (the star haplotype, present in 23 individuals) and 13-10-16-24-9-11-13-12-11-11-11-12-8-10-11 (the Manchu haplotype, present in 27 individuals).

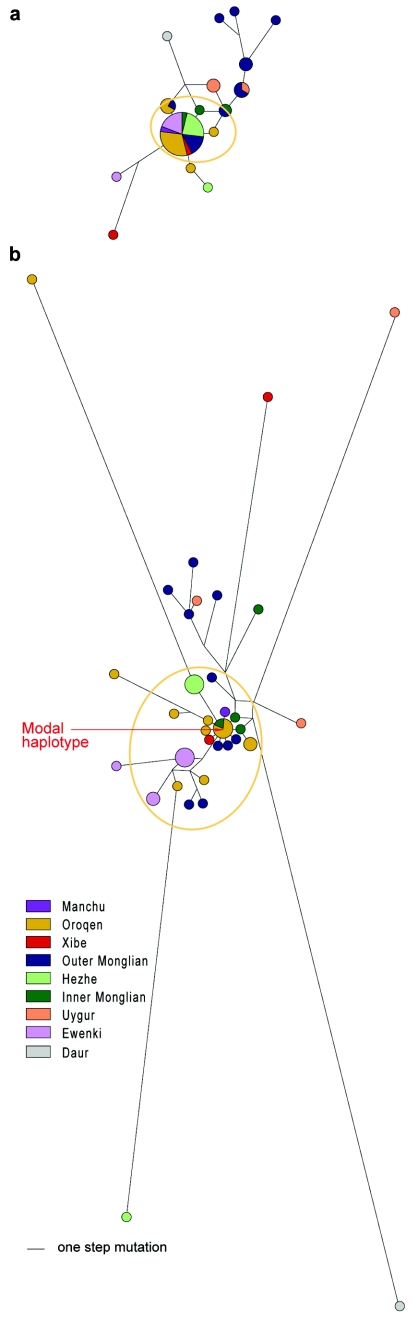

The 1,003 males were tested with 45 binary markers representing the known Y-chromosomal SNP variation in this part of the world (Zerjal et al. 2003; results not shown), and all Manchu haplotype chromosomes were found to carry the derived allele of M48 and, thus, fall into haplogroup C3c. A median-joining network (Bandelt et al. 1999) of this haplogroup showed that closely related chromosomes that might share a common origin were also present, forming a “Manchu cluster” (fig. 2a; data in a tab-delimited ASCII file [online only] that can be imported into a spreadsheet). However, it was not obvious where the boundaries of this cluster lay—chromosomes zero, one, two, three, four, and five steps away from the center were present 27, 7, 3, 5, 3, and 3 times, respectively, showing a decrease in frequency but not a discontinuity. We wished to define the cluster so that we could then map its geographical distribution and estimate its time to the most recent common ancestor (TMRCA), so we needed a definition independent of geography and assumed diversity. We therefore typed the C3c chromosomes with 46 new simple Y STRs (Kayser et al. 2004). The resulting 61-STR network shows, as was expected because of the larger number of markers, considerable resolution within the Manchu cluster and population-specific substructure (fig. 2b). We defined the Manchu cluster as the set of chromosomes linked to the modal haplotype (arrow in fig. 2b), allowing a run of up to three empty nodes. According to this definition, the cluster contains 33 chromosomes: 27/27 at the center of the 15-element network, 5/7 one step away, 1/3 two steps away, and none of the more distant chromosomes (fig. 2a). With this definition, we could examine the distribution and time depth of the cluster.

Figure 2.

Median-joining network of haplogroup C3c Y chromosomes from East Asia. a, Network constructed using 15 Y STRs (Network 4.1.0.9; ASCII file [online only]). The most frequent haplotype is 13-10-16-24-9-11-13-12-11-11-11-12-8-10-11 (DYS388-DYS389I-DYS389b-DYS390-DYS391-DYS392-DYS393-DYS425-DYS426-DYS434-DYS435-DYS436-DYS437-DYS438-DYS439). b, Network constructed using 61 Y STRs (ASCII file [online only]). The modal haplotype (arrow) is 8-12-13-11-8-9-13-14-9-11-10-9-11-16-12-13-10-10-11-10-11-12-11-10-8-11-9-13-15-10-9-10-11-11-10-11-10-10-11-10-9-12-12-15-9-14-13-10-16-24-9-11-13-12-11-11-11-12-8-10-11 (DYS472-DYS508-DYS487-DYS531-DYS583-DYS579-DYS488-DYS589-DYS578-DYS580-DYS636-DYS590-DYS533-DYS617-DYS594-DYS505-DYS641-DYS638-DYS476-DYS492-DYS540-DYS537-DYF406S1-DYS568-DYS480-DYS572-DYS485-DYS490-DYS495-DYS567-DYS494-DYS575-DYS565-DYF390S1-DYS569-DYS618-DYS511-DYS643-DYS556-DYS573-DYS530-DYS491-DYS549-DYS640-DYS554-DYS497-DYS388-DYS389I-DYS389b-DYS390-DYS391-DYS392-DYS393-DYS425-DYS426-DYS434-DYS435-DYS436-DYS437-DYS438-DYS439). In panels a and b, the area of each circle is proportional to the number of chromosomes and line length is proportional to the number of mutations separating haplotypes. The Manchu cluster is circled.

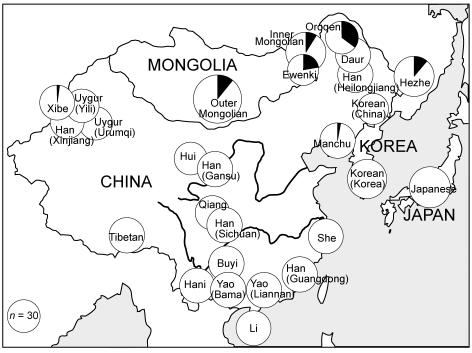

Manchu cluster chromosomes were present in seven populations: Xibe, Outer Mongolians, Inner Mongolians, Ewenki, Oroqen, Manchu, and Hezhe (fig. 3). With the exception of the Xibe, these populations are all located in northeastern China or Mongolia, and the Xibe migrated to their present location in western China from northeastern China in 1764 (Du and Yip 1993). These findings, therefore, suggest that the cluster originated and spread locally in northeastern China/Mongolia and that this happened before the time of the Xibe migration. A more precise estimate of TMRCA (mean ± SD) of the Manchu cluster, from the program Network 4.1.0.9 (Bandelt et al. 1999), was 590 ± 340 years or 220 ± 130 years, depending on whether the inferred (Zhivotovsky et al. 2004) or observed (Kayser et al. 2000; Dupuy et al. 2004) mutation rates were used. The former rate is calibrated for time periods of ∼1,000 years, and the latter is a direct measurement over single-generation times, so the most likely TMRCA is intermediate between these values and will be referred to as ∼500 years.

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of Manchu cluster chromosomes. Circles, Populations sampled, with area proportional to sample size. Filled sectors, Manchu clusters.

We then wished to know whether the haplotype sharing between populations and the rapid expansion were characteristics of the populations as a whole, resulting from the general demography of the area, or were specific to the Manchu cluster. The proportion of 15-STR haplotypes (excluding the Manchu cluster) shared between populations and the ρ distance (the number of steps between a 15-element haplotype in one population and the closest haplotype in a second population, averaged over all haplotypes [Helgason et al. 2000]) were therefore calculated for Mongolian and northeastern Chinese populations (table 1). These measures were not significantly different between populations that carried the Manchu cluster and those that lacked it, showing that the Manchu cluster is exceptional, in that its sharing between populations is a lineage-specific phenomenon rather than a general feature of all lineages in these populations.

Table 1.

Comparisons of Y-STR Lineages (Excluding the Manchu Cluster) in Northern Populations

| Comparison | Lineage Sharinga | ρ Distanceb |

| Between popluations that carry the Manchu cluster | .018 ± .018 | 3.94 ± .63 |

| Between populations that carry the Manchu cluster and those that lack it | .019 ± .019 | 4.28 ± .96 |

| Between populations that lack the Manchu cluster | .012 ± .022 | 4.83 ± 1.01 |

Proportion (mean ± SD) of lineages in a pair of populations that are shared between the populations, averaged over all population pairs.

ρ Distance (mean ± SD) between pairs of populations, averaged over all pairs.

We reasoned that the events leading to the spread of this lineage might have been recorded in the historical record, as well as in the genetic record. The spread must have occurred after the cluster’s TMRCA (∼500 years ago, corresponding to about a.d. 1500) and, most likely, before the Xibe migration in 1764. Notable features are the occurrence of the lineage in seven different populations but its apparent absence from the most populous Chinese ethnic group, the Han. A major historical event took place in this part of the world during this period—namely, the Manchu conquest of China and the establishment of the Qing dynasty, which ruled China from 1644 to 1912. This dynasty was founded by Nurhaci (1559–1626) and was dominated by the Qing imperial nobility, a hereditary class consisting of male-line descendants of Nurhaci’s paternal grandfather, Giocangga (died 1582), with >80,000 official members by the end of the dynasty (Elliott 2001). The nobility were highly privileged; for example, a ninth-rank noble annually received ∼11 kg of silver and 22,000 liters of rice and maintained many concubines. A central part of the Qing social system was the army, the Eight Banners, which was made up of separate Manchu, Mongolian, and Chinese (Han) Eight Banners. The nobility occupied high ranks in the Manchu Eight Banners but not in the Mongolian or Chinese Eight Banners; the Manchu Eight Banners were recruited from the Manchu, Mongolian, Daur, Oroqen, Ewenki, Xibe, and a few other populations. A social mechanism was thus established that would have led to the increase of the specific Y lineage carried by Giocangga and Nurhaci and to its spread into a limited number of populations. We suggest that this lineage was the Manchu lineage.

Our hypothesis could be tested by examining the descendants of the Qing nobility (Li 1997). Unfortunately, extensive warfare during the 20th century and the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) led to enormous social upheaval, during which descent from the nobility was usually hidden and relevant documents were destroyed. As a result, very few well-attested descendants are known, and they were not available for testing. Thus, our hypothetical explanation remains unproven. Nevertheless, it has strong circumstantial support. The 80,000 nobility at the end of the Qing Dynasty would have represented ∼0.8% of the non-Han population of China at that time and, at this frequency, should contribute ∼5 chromosomes to our sample. The number of males carrying this chromosome would have greatly exceeded the officially recognized number of nobility, so the number 5 should be multiplied several times, and the nobility’s chromosomes should be distributed among the Manchu Eight Banner populations. The lineage should, therefore, be detectable in our data set as a widespread, high-frequency northern haplotype. The Manchu cluster is the only lineage that meets these requirements.

It is notable that the two Chinese dynasties that were established by non-Han populations, the Yuan (1279–1368, by Mongolians) and the Qing, both apparently left detectable genetic imprints on the modern Chinese Y-chromosomal pool: the star cluster and the Manchu cluster. No other Y lineages have spread on this scale in this part of the world (fig. 1), but it is likely that major expansions elsewhere, and more local events here, remain to be elucidated.

Acknowledgments

We thank all sample donors for taking part in this study. The work was supported by a joint project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Royal Society and by the Wellcome Trust.

Web Resources

The URL for data presented herein is as follows:

- Network 4.1.0.9, http://www.fluxus-engineering.com/sharenet.htm/

References

- Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Röhl A (1999) Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 16:37–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du R, Yip VF (1993) Ethnic groups in China. Science Press, Beijing [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy BM, Stenersen M, Egeland T, Olaisen B (2004) Y-chromosomal microsatellite mutation rates: differences in mutation rate between and within loci. Hum Mutat 23:117–124 10.1002/humu.10294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MC (2001) The Manchu way: the eight banners and ethnic identity in late imperial China. Stanford University Press, Stanford [Google Scholar]

- Hedman M, Pimenoff V, Lukka M, Sistonen P, Sajantila A (2004) Analysis of 16 Y STR loci in the Finnish population reveals a local reduction in the diversity of male lineages. Forensic Sci Int 142:37–43 10.1016/j.forsciint.2003.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgason A, Sigurðardóttir S, Nicholson J, Sykes B, Hill EW, Bradley DG, Bosnes V, Gulcher JR, Ward R, Stefánsson K (2000) Estimating Scandinavian and Gaelic ancestry in the male settlers of Iceland. Am J Hum Genet 67:697–717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobling MA, Hurles ME, Tyler-Smith C (2004) Human evolutionary genetics. Garland Science, New York [Google Scholar]

- Katoh T, Munkhbat B, Tounai K, Mano S, Ando H, Oyungerel G, Chae GT, Han H, Jia GJ, Tokunaga K, Munkhtuvshin N, Tamiya G, Inoko H (2005) Genetic features of Mongolian ethnic groups revealed by Y-chromosomal analysis. Gene 346:63–70 10.1016/j.gene.2004.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser M, Kittler R, Erler A, Hedman M, Lee AC, Mohyuddin A, Mehdi SQ, Rosser Z, Stoneking M, Jobling MA, Sajantila A, Tyler-Smith C (2004) A comprehensive survey of human Y-chromosomal microsatellites. Am J Hum Genet 74:1183–1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser M, Roewer L, Hedman M, Henke L, Henke J, Brauer S, Kruger C, Krawczak M, Nagy M, Dobosz T, Szibor R, de Knijff P, Stoneking M, Sajantila A (2000) Characteristics and frequency of germline mutations at microsatellite loci from the human Y chromosome, as revealed by direct observation in father/son pairs. Am J Hum Genet 66:1580–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z (1997) Ai Xin Jue Luo Jia Zu Quan Shu [in Chinese]. Ji Lin Ren Min Press, Changchun [Google Scholar]

- Zerjal T, Wells RS, Yuldasheva N, Ruzibakiev R, Tyler-Smith C (2002) A genetic landscape reshaped by recent events: Y-chromosomal insights into central Asia. Am J Hum Genet 71:466–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerjal T, Xue Y, Bertorelle G, Wells RS, Bao W, Zhu S, Qamar R, Ayub Q, Mohyuddin A, Fu S, Li P, Yuldasheva N, Ruzibakiev R, Xu J, Shu Q, Du R, Yang H, Hurles ME, Robinson E, Gerelsaikhan T, Dashnyam B, Mehdi SQ, Tyler-Smith C (2003) The genetic legacy of the Mongols. Am J Hum Genet 72:717–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhivotovsky LA, Underhill PA, Cinnioglu C, Kayser M, Morar B, Kivisild T, Scozzari R, Cruciani F, Destro-Bisol G, Spedini G, Chambers GK, Herrera RJ, Yong KK, Gresham D, Tournev I, Feldman MW, Kalaydjieva L (2004) The effective mutation rate at Y chromosome short tandem repeats, with application to human population-divergence time. Am J Hum Genet 74:50–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]