Abstract

Tessellation of nine free-base porphyrins into a 3 × 3 array is accomplished by the self-assembly of 21 molecular entities of four different kinds, one central, four corner, and four side porphyrins with 12 trans Pd(II) complexes, by specifically designed and targeted intermolecular interactions. Strikingly, the self-assembly of 30 components into a metalloporphyrin nonamer results from the addition of nine equivalents of a first-row transition metal to the above milieu. In this case each porphyrin in the nonameric array coordinates the same metal such as Mn(II), Ni(II), Co(II), or Zn(II). This feat is accomplished by taking advantage of the highly selective porphyrin complexation kinetics and thermodynamics for different metals. In a second, hierarchical self-assembly process, nonspecific intermolecular interactions can be exploited to form nanoscaled three-dimensional aggregates of the supramolecular porphyrin arrays. In solution, the size of the nanoscaled aggregate can be directed by fine-tuning the properties of the component macrocycles, by choice of metalloporphyrin, and the kinetics of the secondary self-assembly process. As precursors to device formation, nanoscale structures of the porphyrin arrays and aggregates of controlled size may be deposited on surfaces. Atomic force microscopy and scanning tunneling microscopy of these materials show that the choice of surface (gold, mica, glass, etc.) may be used to modulate the aggregate size and thus its photophysical properties. Once on the surface the materials are extremely robust.

With the increasing demand for the ability to sculpt matter into precise functioning devices of nanoscale dimensions, the molecular level design of functional materials is an overarching theme in much of the synthetic materials literature (1–7). Inspired by biological systems, the introduction of specific interactions is a route toward using the facile and energetically favorable production capabilities to self-assemble materials (8). Exploitation of nonspecific intermolecular interactions has resulted also in the formation of molecular electronic devices (9–11). We have used self-assembly to form a square planar array of nine porphyrins mediated by coordination of exocyclic pyridyl groups on three different porphyrins to 12 trans-palladium dichlorides (12, 13). In addition to modulating the size and distribution on surfaces, metalation of the porphyrin macrocycle enables one to design nanoscale systems with a host of photonic, magnetic, redox catalytic, and sensor capabilities. These functions have been well studied on metalloporphyrin monomers. Substitution of the peripheral R groups with long-chain hydrocarbons enables the design of nanoscale aggregates that, using nonspecific interactions, organize into two-dimensional arrays (refs. 14–20 and references therein). Here we present an overview of the design capabilities for materials and devices by using porphyrin supramolecular arrays.

Formation of the Free-Base Nonamer Supramolecular Array

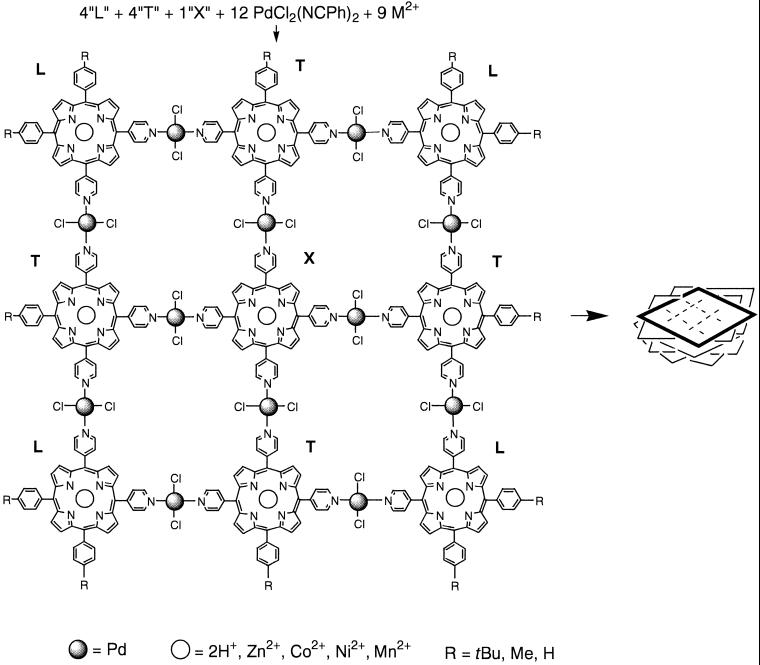

Earlier (12, 13), we reported the synthesis and characterization of a porphyrin nonamer that is self-assembled by the coordination of exocyclic pyridyl groups on nine porphyrins to 12 PdCl2 (Fig. 1). The predefined geometry of either the metallo or free-base porphyrins as well as the coordination geometry of the metal ion linker, all in the correct stoichiometry, dictates the final structure of the self-assembled arrays. In the case of the square planar nonamer, the 180° (trans) coordination geometry of the 12 PdCl2 species combines with four “L-shaped” 5,10-bis(4-pyridyl)-15,20-bis(4-alkylphenyl)porphyrins that serve as the corners, four “T-shaped” 5,10,15-Tris(4-pyridyl)-20-(4-alkylphenyl)porphyrins that constitute the sides, and one “X-shaped” tetrakis(4-pyridyl)porphyrin that resides in the center. Alternatively, the combination of two X-shaped and two L-shaped porphyrins with the 90° (cis) coordination geometry of six PtCl2 linkers results in linear tapes substantially weighted toward the tetramer (12, 13). All these self-assembled arrays were well characterized in solution. This earlier report also contained a preliminary atomic force microscopy (AFM) study that revealed nanoscaled aggregates of the nonameric arrays may be deposited on glass surfaces.

Figure 1.

The self-assembled 30-component metalloporphyrin nonamers (Left) subsequently self-organize into columnar stacks (Right, not to scale). For example, when r = t-butyl and the cobalt porphyrin is in the nonamer, the average height of the stacks on glass is nearly twice that of the stacks formed from the free-base nonamer.

As defined elsewhere (1), specific intermolecular forces are directional and have predefined donor-acceptor interactions such as hydrogen bonds and metal ion coordination, whereas nonspecific intermolecular forces usually have less directionality and no specifically designed donor-acceptor interactions such as electrostatic interactions. Herein we use the former to design and self-assemble discrete supramolecular entities and the latter to self-organize the supramolecules into hierarchical structures.

Differential Metalation

When nine equivalents of a divalent transition metal acetate [Mn(II), Ni(II), Co(II), or Zn(II)] dissolved in methanol is added simultaneously with 12 equivalents of PdCl2Bn2 in toluene to a <10 μM mixture of porphyrins in toluene at 40–50°C, the self-assembly of the 30-component metalloporphyrin nonamer is accomplished in ≈90% yield in 1–3 h, depending on the metal ion. This in situ is possible for several reasons. First it is well known that the kinetics and thermodynamics of porphyrin metalation by the first-row transition metals is substantially different than that of Pd(II) (21). The size of the metal ion, the lability of the counter ions, and the energetics of the metal-porphyrin interaction all affect the yield and rate of the reaction. Thus for most porphyrins the first-row transition metals can be inserted into the core in a few hours or less at temperatures <80°C by using an excess of the acetate salt dissolved in methanol, whereas Pd(II) insertion takes 8–12 h at >120°C. Yet, the efficiency observed for the self-assembly of the metalloporphyrin nonamer also suggests that there are additional considerations, because a stoichiometric quantity of the metal to be inserted is used. As we and others have observed, the insertion of Zn(II) into meso pyridyl porphyrins increases the basicity of the pyridyl nitrogen (12, 13, 22). This increased bacisity is indicated by a concomitant increase in the coordination bond energy between the pyridine moiety and both Pt(II) and Pd(II). The stability of dimers formed from free-base monopyridylporphyrins and either PtCl2 or PdCl2 in toluene is less than the same dimers composed of the zinc-metalated porphyrins by about a factor of two. Inversely, it is reasonable to expect that the exocyclic coordination of Pd(II) or Pt(II) by the pyridyl moieties may increase the binding constant and/or lower the barrier to Zn(II) insertion into the macrocycle via similar electronic effects. Therefore, there is a synergy, or cooperativity, between the metalation of the porphyrins and the formation of the nonameric array (23). Under these conditions, UV-visible spectra indicate that the nonamer is formed before complete metalation of the free-base porphyrins. This in situ result is supported by the observation of the same kinetics for porphyrin metalation of the preassembled nonamer under the same conditions. The electronic perturbation of the macrocycle by exocyclic ligand coordination to these square planar metals is demonstrated also by 2–5 nm red shifts observed in the visible spectra (12, 13, 22).

Secondary Self-Organizing Processes

The initial self-assembly process, the formation of the nonamer, is directed by specifically designed intermolecular forces, stoichiometry, and an understanding of the complexities of the thermodynamics of the self-assembly process. The secondary, hierarchical self-organization of the porphyrin nonamers into columnar aggregates of low polydispersity arises from nonspecific interactions inherent in the supermolecule. The formation of the nanoscaled aggregates of porphyrin nonamers, as in the case of the formation of many nanoscaled colloidal particles, is driven partially by the minimization of surface area and surface energetics. The limited particle size is expected and is manifested in the fact that the aggregates have roughly the same dimensions in all three axes. Thus, the ≈6 × 6-nm square nonamer forms ≈4–6-nm tall columnar stacks (12, 13). Small stacking differences are observed by altering the various pendant R groups, -H, -CH3, and -t-butyl, which can be attributed to packing and somewhat to electronic effects on the π system.

The energetics of self-organization of the columnar stacks of porphyrin nonamers arise from the complex interplay between a variety of intermolecular forces. The π stacking of porphyrins to form face-to-face (H) or edge-to-edge (J) aggregates is a well known and understood phenomenon (12, 13). Electronic spectra indicate that both types of arrangements are present in the columnar aggregates (ref. 20 and references therein). Under the conditions described herein, however, neither solutions of individual porphyrins or a mixture of them nor the palladium complex results in any discernable aggregation as shown by absorption and emission spectra, dynamic light scattering, or AFM. Estimates of π-stacking interactions are between 3 and 5 kcal⋅mol−1 per porphyrin face for mesotetraphenylporphyrin (ref. 20 and references therein). Because the aryl groups are not coplanar with the porphyrin, these substituents also sterically prevent exact alignment of the two macrocycles.

A second internonamer interaction comes from the PdCl2 groups. The electrostatic and steric interactions arising from the Pd2+ and the Cl− ions would tend to place the Cl− from one nonamer over the vacant axial positions of the Pd2+ ions of the adjacent nonamer, over the pyrrole N-H, or in the case of the metalloporphyrins over the Zn(II). The nature of the R groups, and their position on the aryl ring, also influences the kinetics and size of the secondary assembly; small substituents on the para-position favor π stacking, whereas those on ortho and meta positions would prevent significant π stacking. In general, the kinetics are faster, and the resultant hierarchical assemblies are larger as one goes from r = t-butyl to methyl to H. After reaching equilibrium the respective average columnar heights by dynamic light scattering are 6, 7, and 10 nm, and by AFM on glass surfaces 5, 7, and 8 nm. Although the exact geometry of the nanoscaled aggregates is still under investigation, docking experiments suggest that one planar array may stack on top of another in one of either two ways: (i) one is rotated 30–60° relative to the next, or (ii) one is off set diagonally by a little more than half the diameter of a single porphyrin (≈0.6 nm).

Formation of Surface-Bound Structures as Device Precursors

To convert these materials into useful nanoscale devices, their organization and stability after surface deposition must be evaluated. A myriad of devices can be envisioned by using these materials as a platform for their formation. These devices include (i) chemical sensor arrays using changes in the optoelectronic properties of the materials for signaling, (ii) complex three-dimensional storage devices based on the ability of Co(II)-porphyrin nonamers to form organized nanoscale stacks of magnetic materials with varying magnetic properties depending on the number of nonamers in a stack, and (iii) photo-gated magnetic materials wherein the magnetism is gated on or off depending the metalloporphyrin used.

As a precursor to the formation of such devices, we have investigated the adsorption of both free-base and metalloporphyrin nonamers on a variety of surfaces including glass, mica, graphite, and Au(111) thin films. The adsorption properties of the nonamers have been characterized by using a combination of AFM and scanning tunneling microscopy. The free-base materials have shown remarkable stability on glass surfaces and are found to remain intact for more than 1 year under ambient conditions from deposition with no apparent change in the photonic properties by UV-visible or fluorescence spectra.

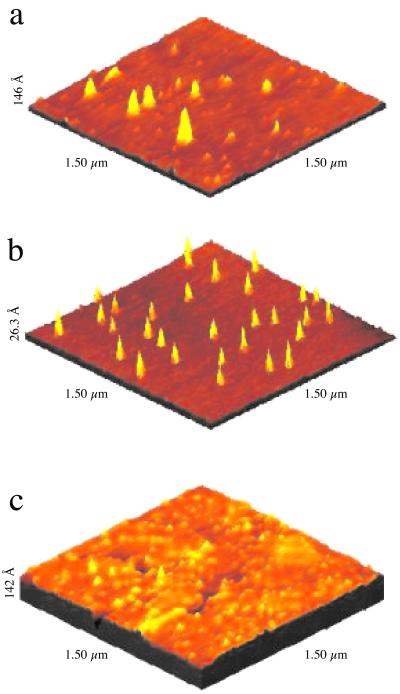

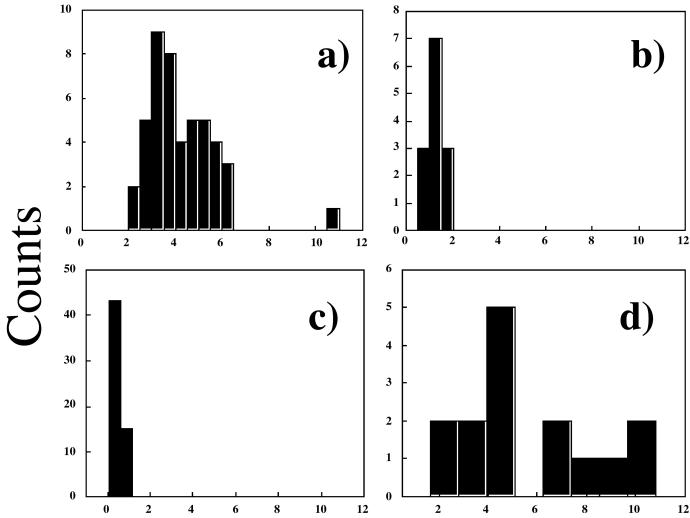

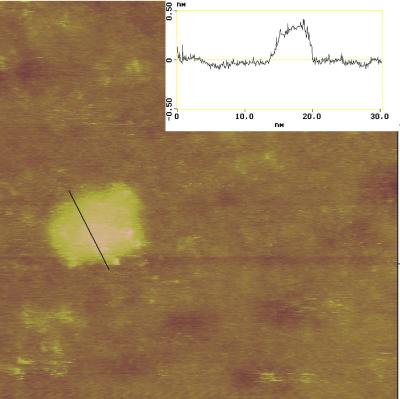

Earlier we reported that the free-base nonamer forms aggregates of ≈5–6 nm3 in size in solution, observed by dynamic light scattering, that remain intact when deposited on the glass surface (12, 13). The aggregate structure on surfaces has been observed by AFM where (caused by the 10–50-nm radius of curvature of the AFM tip), only the aggregate height may be reported. Nonamer aggregates on glass (Fig. 2a) are deposited fairly uniformly in density over the surface with heights of 2–6 nm (Fig. 3a), which corresponds to ≈4–12 stacked nonamer arrays. When the free-base nonamer aggregate is deposited on graphite, the stacks are found to cluster together and are generally shorter (data not shown). On surfaces such as mica (Fig. 3b) or the electron-rich gold surface (Fig. 3c), the nonamer aggregates break apart and form smaller structures of ≈3 nm in height on mica, down to single nonameric arrays (Fig. 3c) when the aggregates are deposited on gold. Scanning tunneling microscopy of the nonamer on gold (Fig. 4) shows that the array is ≈5 × 6 × 0.4 nm in size. Interestingly, single nonameric arrays appear almost exclusively on Au(111) terraces, whereas 2–3-nonamer-high stacks are found to bind to defects such as step edges on the gold surface. The appearance of stacks at defect sites suggests that the aggregate height, thus its optoelectronic properties, may be tuned at the level of single arrays by controlling the strength of the surface dipole of the metal arising from the Smoluchowski effect (24–26). Thus one can envision that the organization of these materials on metal nanoparticles of varying dimensions will exhibit tuned photonic properties because of the number of supermolecules stacked together is controlled by the varying surface dipoles.

Figure 2.

The size of the columnar stack of free-base porphyrin nonamers (r = t-butyl) is determined also by the nature of the surface. On glass (a) aggregates of ≈5–27-nonamer-high stacks are predominantly found, on mica (b) the aggregate density increases as the size decreases (≈5–8-nonamer-high stacks), whereas on Au(111) (c) single nonameric arrays are found typically on the terraces with stacks containing 2–3 arrays at step defects.

Figure 3.

Histograms of the stacking heights taken from topographic AFM measurements for the free-base nonamer (r = t-butyl) on glass (a), mica (b), and gold (c). In an experiment that used 20% less Co(II) than needed to fully metallate the porphyrin nonamer (d), one observes two populations of columnar stacks on glass surfaces as expected. One height is nearly equivalent to the free base, and one is about twice this height, which suggests that the Co(II) nonamers aggregate into larger columnar stacks because of an additional magnetic or electrostatic attraction between the layers.

Figure 4.

Scanning tunneling microscope constant current (I = 250 pA, V = 1.2V) image (29 × 29 nm) of a single nonamer on the Au(111) surface. The line trace (Inset) shows that the nonamer is ≈5–6 nm wide and ≈0.4 nm high.

With metalation, the Zn(II) and Co(II) porphyrin nonamers deposited on glass exhibit divergent properties. In general the Zn(II) nonamers show smaller stack heights on glass than the free base. Preliminary results on Co(II) nonamers, however, show a height distribution nearly double the stack height of the free base (≈9 ± 1 nm), suggesting that the Co(II) porphyrin nonamers have an increased proclivity for stacking. Perhaps the formation of the larger aggregates is caused by the addition of a magnetic attraction between the nonamer layers in the aggregates (Fig. 3d). Preliminary magnetic force microscopy measurements employing cobalt-coated AFM tips suggest that the cobalt nonamers have net magnetic dipoles oriented perpendicular to the surface with the dipole facing out from the surface. Here again, it is expected that the tunability of the stack height dictated by the surface chemistry and electronic properties will afford the controlled formation of nanoscale aggregates with designed magnetic properties.

Conclusions

The height of the columnar aggregates is determined by a balance between the porphyrin π-stacking forces, the electrostatics of the PdCl2 units, and the steric interactions between the meso substituents. These aggregates are remarkably robust and may be deposited on a variety of surfaces, which also affords a means to modulate the particle size, where they have been characterized by scanning probe microscopy. The metalation of the porphyrins in the nonamer can be accomplished either in the self-assembly process or in situ after the formation of the array. Because there are three different porphyrins in the nonameric array, four T, four L, and one X, each type of macrocycle can contain a different metal ion. The advantage of metalating the porphyrins before self-assembly is that up to three different metals can be used and they will reside in predetermined sites in the supermolecule. The metalation state and type of metal ion in the porphyrin are powerful means to modulate the photophysical properties and the chemical reactivity of the nonamers and the nanoscale aggregates. This work dovetails well with other recent work on nanoscaled materials based in inorganic, organic, and organometallic systems (27–33).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support from National Science Foundation Grants CHE-9732950, DGE-9972892, CHE-0095649, and DMR-9809687 and the Professional Staff Congress-City University of New York. Hunter College chemistry department infrastructure is supported partially by National Institutes of Health RCMI program GM3037. H.S. was supported by the National Science Foundation-Research Experience for Undergraduates Program in Polymers and Biopolymers at College of Staten Island (CHE-0097446).

Abbreviation

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

Footnotes

This paper results from the Arthur M. Sackler Colloquium of the National Academy of Sciences, “Nanoscience: Underlying Physical Concepts and Phenomena,” held May 18–20, 2001, at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, DC.

References

- 1.Alivisatos A P, Barbara P F, Castleman A W, Chang J, Dixon D A, Klein M L, McLendon G L, Miller J S, Ratner M A, Rossky P J, Stupp S I, Thompson M E. Adv Mater. 1998;10:1297–1336. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aviram A, Ratner M. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;852:1–349. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehn J-M. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1990;29:1304–1319. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stang P J, Olenyuk B. Acc Chem Res. 1997;30:502–518. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindsey J S. New J Chem. 1991;15:153–180. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujita M, editor. Structure and Bonding. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reed M A. MRS Bull. 2001;26:113–120. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ball P. Nature (London) 2001;409:413–416. doi: 10.1038/35053198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drain C M, Mauzerall D. Biophys J. 1992;63:1556–1563. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81739-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drain C M, Mauzerall D. Bioelectrochem Bioenerg. 1990;24:263–266. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drain C M, Christensen B, Mauzerall D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6959–6962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.6959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drain C M, Nifiatis F, Vasenko A, Batteas J D. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1998;37:2344–2347. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980918)37:17<2344::AID-ANIE2344>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drain C M, Nifiatis F, Vasenko A, Batteas J D. Angew Chem. 1998;110:2478–2481. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980918)37:17<2344::AID-ANIE2344>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox M A. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarno D M, Jiang B, Grosfeld D, Afriyie J O, Matienzo L J, Jones W E., Jr Langmuir. 2000;16:6191–6199. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiu X, Wang C, Zeng Q, Xu B, Yin S, Wang H, Xu S, Bai C. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:5550–5556. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu C-Y, Pan H-I, Fox M A, Bard A J. Science. 1993;261:897–899. doi: 10.1126/science.261.5123.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chambron J-C, Heitz V, Sauvage J-P. In: The Porphyrin Handbook. Kadish K M, Smith K M, Guilard R, editors. Vol. 6. New York: Academic; 2000. pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou J-H, Kosal M E, Nalwa H S, Rakow N A, Suslick K S. In: The Porphyrin Handbook. Kadish K M, Smith K M, Guilard R, editors. Vol. 6. New York: Academic; 2000. pp. 43–133. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter C A, Sanders J K M. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:5525–5534. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buchler J W. In: Porphyrins and Metalloporphyrins. Smith K M, editor. New York: Elsevier; 1975. pp. 157–224. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Drain, C. M. & Lehn, J.-M. (1994) Chem. Commun. 2313–2315.

- 23.Sharma C V K, Broker G A, Huddleston J G, Baldwin J W, Metzger R M, Rogers R D. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:1137–1144. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCarty G S, Weiss P S. Chem Rev (Washington, DC) 1999;99:1983–1990. doi: 10.1021/cr970110x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smoluchowski R. Phys Rev Lett. 1941;60:661–674. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schenning A P H J, Benneker F B G, Geurts H P M, Liu X Y, Nolte R J M. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:8549–8552. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puntes V F, Krishnan K M, Alivisatos A P. Science. 2001;291:2115–2117. doi: 10.1126/science.1057553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banfield J F, Welch S A, Zhang H Z, Ebert T T, Penn R L. Science. 2000;289:751–754. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zubarev E R, Pralle M U, Sone E D, Stupp S I. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:4105–4106. doi: 10.1021/ja015653+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diaz J D, Storrier G D, Bernhard S, Takada K, Abruña H D. Langmuir. 1999;15:7351–7354. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung T A, Schlitter R R, Gimzewski J K. Nature (London) 1997;386:696–698. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wurthner F, Thalacker C, Sautter A. Adv Mater. 1999;11:754–758. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurth D G, Lehmann P, Schutte M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5704–5707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.5704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]