Abstract

A part (12 kb) of a plasmid containing the β-lactamase genes of Tn552, the disinfectant resistance gene qacA, and flanking DNA has been cloned from a Staphylococcus haemolyticus isolate and sequenced. This region was used to map the corresponding regions in six other multiresistant S. haemolyticus isolates of human and animal origin. The organizations of the genetic structures were almost identical in all isolates studied. The β-lactamase and qacA genes from S. haemolyticus have >99.9% identities at the nucleotide level with the same genes from S. aureus, demonstrating that various staphylococcal species able to colonize animal and human hosts can exchange the genetic elements involved in resistance to antibiotics and disinfectants. The use of antibiotics and disinfectants in veterinary practice and animal husbandry may also contribute to the selection and maintenance of resistance factors among the staphylococcal species. Different parts of the 12-kb section analyzed had high degrees of nucleotide identity with regions from several other different Staphylococcus aureus plasmids. This suggests the contribution of interplasmid recombination in the evolutionary makeup of this 12-kb section involving plasmids that can intermingle between various staphylococcal species. The lateral spread of resistance genes between various staphylococcal species is probably facilitated by the generation of large multiresistance plasmids and the subsequent interspecies exchange of them.

The coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) have traditionally been considered nonpathogenic commensals. In recent years bacteria within this group have become increasingly recognized as important pathogens associated with disease in both animals and humans (1, 7, 26). The coagulase-negative skin commensal Staphylococcus haemolyticus has been associated with a variety of infections in humans, and these infections particularly affect individuals with compromised host defenses and individuals with implanted foreign bodies (7, 20). The finding of S. haemolyticus in cases of bovine mammary gland infection is not uncommon (1, 10, 11), and the bacterium has been associated with canine urinary tract infection (26).

Resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents has frequently been found among clinical isolates of S. haemolyticus (32). In addition to being a potential pathogen, multiresistant S. haemolyticus could possibly also serve as a donor of resistance genes to the more virulent staphylococci such as coagulase-positive Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus intermedius. The finding of closely related plasmids and resistance elements among bacteria within the staphylococcal group suggests that horizontal gene transfer has taken place (28).

Production of β-lactamase is one of the mechanisms by which staphylococci become resistant to β-lactam antibiotics. The blaZ β-lactamase gene and two linked genes controlling its expression, blaI and blaR, have been identified on several different transposons (15, 23). Transposon Tn552 contains the three genes involved in β-lactamase production, and they constitute the right half of the transposon (the Tn552 bla gene module). The left half of Tn552 (the mobility module) comprises the genes p480, which encodes a transposase; p271, which encodes a potential ATP-binding protein; binL, which encodes a recombinase; and a resolution site, resL. Tn552 is flanked by inverted terminal repeats of 116 bp (TIRL and TIRR) (23, 24). The presence of intact transposons and insertion sequence (IS) elements may lead to a variety of genetic rearrangements including deletions, inversions, and translocations. The structure of naturally occurring staphylococcal plasmids indicates that a variety of large-scale rearrangements involving β-lactamase genes have occurred during evolution (23).

Increased tolerance to disinfecting agents can be caused by energy-dependent efflux pumps located in the cell membrane (6, 12, 14, 16). The genes encoding multidrug exporter proteins among staphylococci can be divided into two families on the basis of DNA homology and phenotypic properties (14, 18, 21). Members of the qacA-qacB family confer a resistance phenotype broader than that conferred by members of the smr family (13). The qacA and qacB genes are closely related and differ at the nucleotide level by seven nucleotides. A single amino acid alteration (Ala in qacB→Asp in qacA, codon 323) is probably responsible for the differences in phenotypic expression, which gives a broader resistance phenotype in isolates harboring qacA (18, 19).

In this study we have investigated the organization of Tn552 and derivatives of the transposon on large S. haemolyticus plasmids originating from animal and human sources. The nucleotide sequence of an approximately 12-kb section comprising β-lactamase genes, a disinfectant resistance gene, and flanking DNA has been determined. The sequence has been aligned with corresponding regions found in S. aureus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of seven multiresistant S. haemolyticus strains were included in this work. Four of the isolates (isolates NVH95A, NVH95B, NVH97A, and NVH97B) originated from the floors of animal cages in a small-animal veterinary clinic. These isolates belonged to a particular strain that had persisted for more than 1 year in the clinic, despite accurate routines concerning washing and disinfection (H. Oppegaard, M. S. Sidhu, T. P. Devor, and H. Sørum, submitted for publication). In addition, one isolate (isolate NVH98) from a wound of a cat being hospitalized at the small-animal clinic was included in the study. For comparison, two isolates from different sources were also included. One (isolate NVH407/97) originated from a dairy cow with a mammary gland infection, and the other (isolate NVHRH) originated from a human with septicemia. All isolates were identified as S. haemolyticus with the StaphZym kit (Rosco Diagnostica, Taastrup, Denmark).

All isolates except the isolate of human origin had previously been subjected to susceptibility testing (Oppegaard et al., submitted). The isolates produced β-lactamase and expressed resistance to a broad range of antibacterial agents like ampicillin, cefalexin, oxacillin, tetracycline, trimethoprim, sulfadiazine, and streptomycin. Isolate NVH95B also expressed resistance to gentamicin. The mecA determinant responsible for expression of methicillin resistance has been detected in the isolates (Oppegaard et al., submitted).

The human isolate (isolate NVHRH) was subjected to susceptibility testing in the present study by a standard microdilution method and a standard disk diffusion method. This isolate expressed resistance to the same antimicrobial compounds as isolate NVH95B.

Determination of MICs of disinfecting agents and ethidium bromide.

The MICs of benzalkonium chloride, chlorhexidine, and ethidium bromide were determined as described previously (31). S. haemolyticus DSM 20623 was included as a sensitive control.

Isolation of total DNA and plasmid DNA and curing of resistance plasmids pNVH97A and pNVH97B.

Total DNA and plasmid DNA were extracted by using the Easy-DNA extraction kit and the S. N. A. P. Miniprep kit, respectively, both of which were purchased from Invitrogen Corp. (Groningen, The Netherlands). Prior to the lysis step the staphylococcal cell walls were degraded by treatment with lysostaphin (Fluka Chemie, Buchs, Switzerland) for 90 min at 37°C. Strains NVH97A and NVH97B were cured of plasmids conferring resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds and ethidium bromide by using novobiocin (9). These strains are designated NVH97A(cured) and NVH97B(cured), respectively.

PCR.

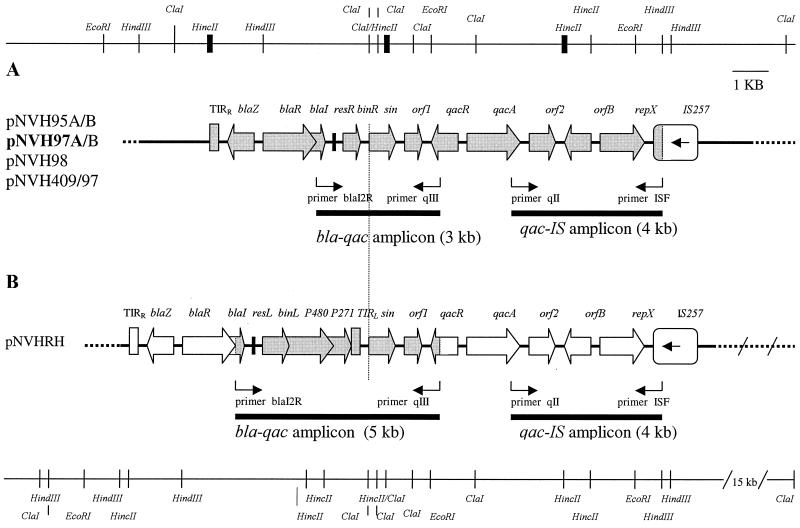

PCR was carried out for detection of the blaZ, blaI, blaR, and p480 genes as described previously (5, 33). The disinfectant resistance gene qacA/B was detected by PCR with the primers listed in Table 1. The cycling conditions were as follows: DNA denaturation at 95°C for 60 s and 30 cycles of 95°C for 60 s and 40°C for 30 s, followed by 72°C for 60 s. The GeneAmp XL PCR kit (Perkin-Elmer Cetus Corp, Norwalk, Conn.) was used for amplification of the DNA region between the β-lactamase genes and the disinfectant resistance gene qacA (the bla-qac amplicon obtained with primers blaI2R and qIII; see Fig. 1) and for amplification of the DNA region between qacA and staphylococcal insertion element IS257 (the qac-IS amplicon obtained with primers qII and ISF; see Fig. 1). The composition of each 50-μl PCR mixture was as recommended by the manufacturer, and the cycling conditions were as follows: DNA denaturation at 93°C for 2 min and 25 cycles of 93°C for 1 min, 45 or 47°C for 45 s, and 70°C for 5 min. After the last cycle, the temperature was kept at 72°C for 10 min. The annealing temperatures were 45°C with primers blaI2R and qIII and 47°C with primers qII and ISF.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in PCR experiments

| Oligonucleotide | Primer sequence (5′→3′) | Nucleotide position in published sequence | EMBL accession no. | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaI F | ATGTCTCGCAATTCTTCAA | 3190-3208 in blaI | X52734 | 24 |

| blaI R | CTATGGCTGAATGGGAT | 3520-3504 in blaI | X52734 | 24 |

| blaI 2R | CAAAGAAATTGAAGAATTGCGA | 3195-3216 in blaI | X52734 | 24 |

| blaR F | CATCTGATAAATGTGTAGC | 3612-3630 in blaR | X52734 | 24 |

| blaR R | GGTATCTAACTCTTCTTGC | 5177-5159 in blaR | X52734 | 24 |

| blaZ 2F | GAGGCTTCAATGACATATAGTG | 5741-5762 in blaZ | X52734 | 24 |

| blaZ 2R | TCTATCTCATATCTAACTGG | 5874-5855 in blaZ | X52734 | 24 |

| p480 F | GGGCAAGCAATCTTTATCAAGC | 2244-2223 in p480 | X52734 | 24 |

| p480 R | CGTTTCTTGAGGTGAGTAACC | 936-956 in p480 | X52734 | 24 |

| qacA/B F | GCTGCATTTATGACAATGTTTG | 1692-1713 in qacA | X56628 | 18 |

| qacA/B R | AATCCCACCTACTAAAGCAG | 2321-2302 in qacA | X56628 | 18 |

| qII | CTGCTTTAGTAGGTGGGATT | 2302-2321 in qacA | X56628 | 18 |

| qIII | TTTAAATGGCGAATGGTGT | 267-249 in qacR | X56628 | 18 |

| IS F | CAACGAAGGTAGCAATGGC | 46122-46140 in IS257 | AF051917 | 4 |

| vga F | ATTCTATTGTCGTTTCATGACG | 9500-9521 | AJ400722 | This study |

| vga R | CCTCTCCCTTACTTTCGTTTG | 11276-11256 | AJ400722 | This study |

FIG. 1.

Physical map of the 12-kb region analyzed in this study containing the β-lactamase genes (the Tn552 bla gene module), antiseptic resistance gene qacA, and a vga-like plasmid inserted downstream of orf2. (A) Organization of bla genes, qacA, and surrounding genes in four strains isolated from the environment of a small-animal veterinary clinic and in two clinical isolates from animals. (B) Organization of bla genes, qacA, and surrounding genes in a clinical isolate of human origin. The bold lines on the restriction map at the top represent the borders of the two cloned HincII fragments of pNVH97A. Shaded genes represent the areas sequenced. pNVH97A (bold) is the only plasmid from which the 12-kb region was completely sequenced. The region was sequenced in four parts: the two HincII clones, the 3-kb bla-qac amplicon, and the 4-kb qac-IS amplicon. The organization of the genes in the remaining animal strains and the human strain was based on hybridization experiments (Table 2) and amplification and sequencing of the bla-qac amplicons of 3 and 5 kb, respectively.

The PCR products that were sequenced were cloned prior to the sequencing reaction by using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Amplification of the DNA region between the qacA gene and staphylococcal insertion element IS257 produced an amplicon of approximately 4 kb (the qac-IS amplicon; see Fig. 1) that was difficult to clone. Therefore, the amplicon was purified by using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and the purified DNA was directly used as the template in the sequencing reactions. An internal primer set was constructed on the basis of the sequences obtained, and these primers (primers vga F and vga R) were used in a nested PCR. The 1.8-kb PCR amplicon produced was cloned by using the TOPO TA cloning kit, and the insert was sequenced by standard procedures.

Hybridization experiments.

Plasmid DNA and restriction enzyme-digested total DNA from all isolates (as well as the two isolates cured of their plasmids conferring resistance to disinfecting agents) were blotted to nylon membranes (Hybond N+; Amersham International, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) by Southern blotting (25). The restriction enzymes used were HincII, HindIII, EcoRI, and ClaI from Gibco BRL (Gaithersburg, Md.). A 22-mer oligonucleotide probe specific for the qacA and qacB genes was used in the hybridization experiments as described elsewhere (8). PCR products amplified with primers specific for the genes blaZ, blaR, and blaI were labeled in vitro with [α-32P]dCTP (Amersham) by using a Random Primed DNA labeling kit (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and used as probes. Prehybridization, hybridization, and washings were carried out at 65°C. All prehybridizations were carried out for 2 h in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-5× Denhardt's solution, followed by hybridization for 18 h in 2× SSC-0.1% SDS-5× Denhardt's solution with 10% dextran sulfate. Washings were performed in 5× SSC-0.1% SDS for 1 h twice and then for 30 min twice. The membranes were finally exposed to autoradiography film (Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.) at −70°C.

Cloning of HincII fragments containing Tn552 and the qacA/B gene.

Total DNA from isolate NVH97A was restricted with HincII, and separation of the DNA fragments was performed in 0.7% low-melting-point agarose (Amersham). Fragments ranging from approximately 4 to 6 kb were excised from the gel and ligated into pUC18 digested with SmaI-bacterial alkaline phosphatase (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) in the slabs of the low-melting-point agarose gel as described by Sambrook et al. (25). T4 DNA ligase buffer (5×) and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from Gibco BRL. The ligation mixture was used to transform electrocompetent Escherichia coli (ElectroMAX DH10B; Gibco BRL) by electroporation with a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser apparatus. One microliter of the ligation mixture was added to 40 μl of cells in 0.2-cm cuvettes (Bio-Rad). The following Gene Pulser parameters were used: voltage, 2.5 kV; capacitance, 25 μF; and pulse controller, 200 Ω. After a single pulse, 1 ml of Super broth (3% tryptone, 2% yeast extraction, 1% morpholinepropanesulfonic acid [MOPS]) was added to the cells, followed by incubation at 37°C for 1 h before plating of the cells on Luria agar containing 50 μg of ampicillin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) per ml. Colony blots containing DNA from the transformants were made as described elsewhere (25). Prior to hybridization the membranes were washed in 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8)-1 mM NaCl-1 mM EDTA-0.01% SDS for 1 h at 37°C, followed by prehybridization and hybridization as described earlier. The probes used were labeled qacA/B and blaI amplicons. Strongly hybridizing colonies were picked, plasmids were isolated, and plasmid DNA was used as the template in sequencing reactions.

Nucleotide sequencing.

Nucleotide sequences were determined with an ABI Prism Big Dye Terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (Perkin-Elmer, Oslo, Norway) with synthetic oligonucleotide primers (primer walking) and/or M13 forward and reverse primers. The sequencing reactions were run on a Perkin-Elmer ABI Prism 377 automatic sequencer. The nucleotide sequences were analyzed by using the Sequencher software package (version 3.0; Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, Mich.) and the GCG Sequence Analysis Software package (version 8; Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported in this study has been assigned accession number AJ400722 in the GenBank/EMBL database.

RESULTS

MICs of disinfecting agents and ethidium bromide.

The strains included in the study had decreased susceptibilities to benzalkonium chloride, chlorhexidine, and ethidium bromide, with MICs of ≥5, ≥1.5, and ≥300 μg/ml, respectively. The MICs of the same three compounds for the control strain were ≤1, ≤0.5, and ≤50 μg/ml, respectively.

PCR and hybridization experiments.

The blaZ, blaI, and blaR β-lactamase genes were detected by PCR in all isolates. The transposase gene of Tn552, p480, was detected only in the strain of human origin (strain NVHRH). PCR with primers specific for the qacA/B disinfectant resistance gene produced amplicons of the expected size (628 bp) with templates derived from all isolates. Sequence analysis of the qacA/B-specific amplicons demonstrated that the qacA gene was present in all isolates. The qacA and β-lactamase genes were not detected in the two isolates cured of their plasmids conferring resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds and ethidium bromide.

Hybridization experiments showed that qacA and blaZ, blaI, and blaR were located on a plasmid of approximately 45 kb in all strains. The isolates NVH97A(cured) and NVH97B(cured) did not contain the 45-kb plasmid, and total DNA from these strains did not hybridize to any of the probes specific for the β-lactamase and qacA genes.

All strains from the animal clinic, the strain from the hospitalized cat, and the strain from the dairy cow had identical hybridization patterns, whereas the strain of human origin had a distinct hybridization pattern. This is illustrated in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Overview of the different isolates and their hybridization patterns after hybridization of total DNA to blaZ, blaR, blaI, and qacA-qacB probesa

| Isolate(s) | Hybridization pattern (fragment size [kb])

|

Enzymes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaZ | blaR | blaI | qacA-qacB | ||

| NVH95A, NVH95B, NVH97A, NVH97B, NVH98, NVH409/97 | 3.5, 9, 5, 5.5 | 12, 9, 5, 5.5 | 12, 9, 5, 5.5 | 12, 5.5, 5, 9 | HindIII, EcoRI, HincII, ClaI |

| NVHRH | 4 + 1.7, 10, 5.5, 9 | 14, 10, 5.5, 9 | 14, 10, 5.5, 9 | 14, 5.5, 9, 23 | HindIII, EcoRI, HincII, ClaI |

| NVH97A(cured), NVH97B(cured) | HindIII, EcoRI, HincII, ClaI | ||||

Notice the identical hybridization pattern for all isolates except human isolate NVHRH.

Genetic organization of the β-lactamase and qacA genes in isolate NVH97A.

Total DNA from isolate NVH97A (from the small-animal clinic) was restricted with HincII and cloned into pUC18. The nucleotide sequences of two different clones hybridizing to blaI- and qacA/B-specific probes revealed the following organization of the genetic structures involved: a derivative of Tn552, consisting of the Tn552 bla gene module (right half of the transposon), was localized adjacent to a resolution site (resR), followed by resolvase gene binR, open reading frame orf1, and recombinase-encoding gene sin. The qacA gene was situated downstream of sin and was flanked by its regulatory gene, qacR, and open reading frame orf2. The organization and contents of the two HincII clones are shown in Fig. 1A. PCR with primers hybridizing to specific regions within the two HincII fragments was carried out (data not shown) in order to prove that the two fragments were joined. An amplicon of the expected size was produced and subsequently sequenced.

Detection of IS257, orfB, and repX downstream of qacA in isolate NVH97A.

Staphylococcal insertion element IS257 (22) was found to be located approximately 4 kb away from and downstream of the qacA gene. This was detected by XL-PCR (with primers qII and IS F), which generated an amplicon of approximately 4 kb (the qac-IS amplicon). Nucleotide sequencing revealed that the orfB (3) and repX (3) genes were situated between IS257 and orf2, as illustrated in Fig. 1A.

Mapping of bla-qacA region and flanking DNA in the remaining strains.

The three other strains from the animal clinic (strains NVH95A, NVH95B, and NVH97B), the strain from a cat (strain NVH98), and the strain from a dairy cow (strain NVH409/97) contained a 12-kb section equal to the one described from pNVH97A (Fig. 1A). These findings were based on the results of hybridization experiments (Table 2) and amplification of the regions between blaI and qacR (the bla-qac amplicon) and between qacA and IS257 (the qac-IS amplicon) (Fig. 1A). The bla-qac amplicons from all strains were partially sequenced. The isolate of human origin (strain NVHRH) contained a section nearly identical to the one found in the other strains except for the presence of a complete Tn552 sequence (Fig. 1B). The transposon was inserted with the mobility module (the left half) adjacent to sin, orf1, qacR, and qacA. The findings were based on hybridization experiments (Table 2) and amplification of the bla-qac and qac-IS amplicons (Fig. 1B). A complete nucleotide sequence was determined for the bla-qac amplicon from NVHRH.

Sequence alignment of the bla-qacA region in three strains of diverse origins.

A complete nucleotide sequence was also determined for the region between blaI and qacR in the strain of bovine origin (by sequencing of the bla-qac amplicon). A comparison of the sequence with the corresponding regions in the strain of human origin (strain NVHRH) and in strain NVH97A showed that the blaI, sin, orf1, and qacR sequences (approximately 3 kb) were 100% identical in all three strains.

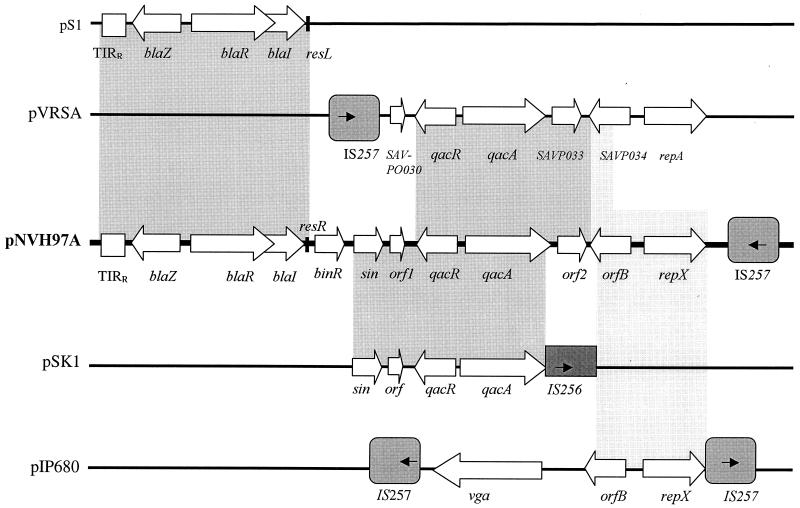

DNA identity with S. aureus sequences.

The blaZ, blaR, and blaI β-lactamase genes on pNVH97A showed very high levels of identity at the nucleotide level (identities of coding regions, >99.9%) with the β-lactamase genes on S. aureus plasmids pS1 (EMBL accession no. X52734) and pI258 (EMBL accession no. M62650 [34]). The nucleotide sequence of the putative recombinase-encoding gene, sin, was 100% identical to those of the sin genes on S. aureus plasmids pSK1 (EMBL accession no. L23109 [17]) and pSR1 (EMBL accession no. AF 167161). The nucleotide sequence of orf1, situated between sin and qacR, was 100% identical to those of orf4 on pSR1 and orf on pSK1. The nucleotide sequence of the qacR gene on pNVH97A was 100% identical to those of qacR on pSK1 (EMBL accession no. X56628 [21]) and qacR on pVRSA (EMBL accession no. AP 003367 [12]). The nucleotide sequence of qacA from S. haemolyticus was 100% identical to that of qacA on pVRSA and 99% identical to that of qacA on pSK1. The nucleotide sequence of orf2 was 100% identical to that of SAVP033 on pVRSA, except for a nucleotide change (position 8505 in our sequence) that resulted in an open reading frame that is nine amino acids shorter. The first 290 nucleotides of orf2 were also 100% identical to the nucleotide sequence of orf186 on S. aureus plasmid pSK156 (EMBL accession no. AF 053771).

The nucleotide sequence of repX on pNVH97A is approximately 88% identical to that of repX on S. aureus plasmid pIP680 (EMBL accession no. AF117259 [3]). Plasmid pIP680 carries streptogramin resistance genes, and repX is localized adjacent to the putative open reading frame orfB and the vga gene, which encodes an ATP-binding protein (Fig. 2) (3). The nucleotide sequences of the genes on pNVH97A are to some degree different from those on the corresponding region on pIP680: the homology between the first 170 amino acids of the two orfB genes is significant. However, the following 20 amino acids are very different between the two orfB genes. The coding region of orfB on pIP680 ends there, whereas orfB on pNVH97A encodes 55 more amino acids. On pNVH97A an approximately 100-bp sequence identical to the sequence of a region prior to the coding region of the vga gene was found downstream of orfB, whereas the rest of the vga gene was absent.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the approximately 12-kb sequence of pNVH97A to other known plasmid sequences (represented by thin lines). Grey boxes represent regions with high levels of sequence identity (from about 90% for the boxes in light grey to more than 98% for the boxes in darker grey), arrows in IS256 and IS257 denote the directions of the respective transposases, while wider arrows denote the different genes and the directions of those genes. Sources: pIP680, EMBL accession no. AF117259; pS1, EMBL accession no. X52734; pVRSA, EMBL accession no. AP003367; pSK1, EMBL accession nos. X56628 and L23109.

Our investigation shows that several sections within the 12-kb region that we analyzed have high degrees of identity at the nucleotide level with regions from several other S. aureus plasmids. This is illustrated in Fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

The strains included in this study originated from different sources and distant geographic areas, and all strains were found to harbor a 45-kb plasmid with a 12-kb region containing a cluster of resistance determinants. The organizations of the genetic structures within this region were almost identical in all strains. The nucleotide sequences of part of blaI, sin, orf1, and qacR (constituting 3 kb) in strains from the small-animal clinic (strain NVH97A), a dairy cow (strain NVH407/97), and a human (strain NVHRH) were 100% identical when they were aligned. This suggests that these genes are related and probably have a common origin of recent date. Investigations recently carried out by Oppegaard et al. (submitted) revealed that the strains of animal origin were closely related and perhaps represent clonal derivatives. The human strain was distinct from the other isolates and thus represented another clone. The fact that the nucleotide sequences of different clones of S. haemolyticus were 100% identical suggests that horizontal DNA transfer might have occurred between these clones and between strains able to colonize human and animal hosts. The use of antibiotics and disinfectants in veterinary practice and animal husbandry may also contribute to the selection and maintenance of resistance factors among the various staphylococcal species.

It has been proposed that large staphylococcal multiresistance plasmids have developed by cointegration of smaller resistance plasmids within a preexisting conjugative plasmid (4, 29). Staphylococcal insertion element IS257 has played a central role in such cointegration events. Large conjugative plasmid pSK41 has integrated several small plasmids, and the cointegrated plasmids within pSK41 are all flanked by copies of IS257 (4). Staphylococcal plasmids carrying the three genes conferring streptogramin resistance, vat, vgb, and vga (2), have been detected in staphylococcal strains belonging to three different taxa (3). All these streptogramin resistance plasmids had in common a 12.1-kb fragment carrying the three genes involved in conferring streptogramin resistance. It is proposed that the creation of this 12.1-kb region is a result of cointegration of two smaller plasmids in which one of the precursor plasmids was a functional vga plasmid (Fig. 2) (3). We have identified in our strains a plasmid region that to a great extent corresponds to a part of a vga-like plasmid. These findings suggest that cointegration of a vga-like plasmid might have taken place downstream of orf2 on the large S. haemolyticus plasmids described in this study. The absence of the vga gene except for a 100-bp stretch prior to the coding region supports the theory that a rearrangement event has taken place within this area. In addition, orf2 has 100% sequence identity with SAVP033 on pVRSA, except that orf2 is nine amino acids shorter than SAV033, confirming that a recombination has taken place within the area.

The presence of large plasmids on which the Tn552 bla gene module and the binR and sin genes are organized in a way similar to the way in which they are organized on S. aureus plasmids pI258 and pI1066 (5) is demonstrated in S. haemolyticus (Fig. 1A). This suggests that these genetic structures have a common organization and that large plasmids containing them have a widespread distribution among different staphylococcal species. The qacA gene has previously been detected among CoNS (13) and among S. aureus isolates, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus isolates (6, 12, 14, 16, 18, 21, 27, 28). The localization of the qacA/B genes in close association with β-lactamase transposons seems to be common, as this has been detected on several S. aureus plasmids. We have shown that such an organization also appears in CoNS.

The β-lactamase and qacA genes from S. haemolyticus have >99.9% identities at the nucleotide level with the same genes from S. aureus, indicating that various staphylococcal species that are able to colonize both animal and human hosts can exchange genetic elements involved in resistance to antibiotics and disinfectants.

The selection of multiresistant commensals is critical, as such bacteria might represent a reservoir of resistance genes that can be transmitted to other bacteria. This study demonstrates the existence of multiresistant commensals containing resistance determinants identical to those found in clinical isolates of S. aureus, thus demonstrating that staphylococcal commensals can be regarded as a reservoir of resistance genes. The striking similarity between the DNA sequences from S. haemolyticus and a methicillin-resistant S. aureus strain with vancomycin resistance (pVRSA in Fig. 2) (12) strengthens the theory that CoNS have contributed resistance factors to the creation of highly resistant S. aureus isolates.

The 12-kb fragment analyzed in this work demonstrates a remarkable clustering of both intact and partial resistance determinants within a limited region. Different areas within this 12-kb section have a high degree of nucleotide sequence identity with regions from several other different S. aureus plasmids, as illustrated in Fig. 2. This suggests the contribution of interplasmid recombination in the evolutionary makeup of this 12-kb section involving plasmids that can intermingle among various staphylococcal species.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Egil Lingaas, Rikshospitalet, Oslo, Norway, for donating strain NVHRH.

This work was partly supported by a grant from the Norwegian Research Council (grant 117131/112).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarestrup, F. M., H. C. Wegener, V. T. Rosdahl, and N. E. Jensen. 1995. Staphylococcal and other bacterial species associated with intramammary infections in Danish dairy herds. Acta Vet. Scand. 36:475-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allignet, J., S. Aubert, A. Morvan, and N. El Solh. 1996. Distribution of genes encoding resistance to streptogramin A and related compounds among staphylococci resistant to these antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2523-2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allignet, J., and N. El Solh. 1999. Comparative analysis of staphylococcal plasmids carrying streptogramin-resistance genes. Plasmid 42:134-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg, T., N. Firth, S. Apisiridej, A. Hettiaratchi, A. Leelaporn, and R. A. Skurray. 1998. Complete nucleotide sequence of pSK41: evolution of staphylococcal conjugative multiresistance plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 180:4350-4359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derbise, A., K. G. H. Dyke, and N. El Solh. 1995. Rearrangements in the staphylococcal β-lactamase encoding plasmid, pIP1066, including a DNA inversion that generates two alternative transposons. Mol. Microbiol. 17:769-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillespie, M. T., J. W. May, and R. A. Skurray. 1986. Plasmid-encoded resistance to acriflavine and quaternary ammonium compounds in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 34:47-51. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gunn, B. A. 1989. Comparative virulence of human isolates of coagulase-negative staphylococci tested in an infant mouse weight retardation model. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:507-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heir, E., G. Sundheim, and A. L. Holck. 1995. Resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds in Staphylococcus spp. isolated from the food industry and nucleotide sequence of the resistance plasmid pST827. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 79:149-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heir, E., G. Sundheim, and A. Holck. 1998. The Staphylococcus qacH gene product: a new member of the SMR family encoding multidrug resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 163:49-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarp, J. 1991. Classification of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from bovine clinical and subclinical mastitis. Vet. Microbiol. 27:151-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jonsson, P., and T. Wadström. 1993. Staphylococcus, p. 21-35. In C. L. Gyles and C. O. Thoen (ed.), Pathogenesis of bacterial infections in animals, 2nd ed. Iowa State University Press, Ames.

- 12.Kuroda, M., T. Ohta, I. Uchiyama, T. Baba, H. Yuzawa, I. Kobayashi, L. Cui, A. Oguchi, K. Aoki, Y. Nagai, J. Lian, T. Ito, M. Kanamori, H. Matsumaru, A. Maruyama, H. Murakami, A. Hosoyama, Y. Mizutani-Ui, N. Kobayashi, T. Sawano, R. Inoue, C. Kaito, K. Sekimizu, H. Hirakawa, S. Kuhara, S. Goto, J. Yabuzaki, M. Kanehisa, A. Yamashita, K. Oshima, K. Furuya, C. Yoshino, T. Shiba, M. Hattori, N. Ogasawara, H. Hayashi, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Whole genome sequencing of the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 357:1225-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leelaporn, A., I. T. Paulsen, J. M. Tennent, T. G. Littlejohn, and R. A. Skurray. 1994. Multidrug resistance to antiseptics and disinfectants in coagulase-negative staphylococci. J. Med. Microbiol. 40:214-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Littlejohn, T. G., I. T. Paulsen, M. T. Gillespie, J. M. Tennent, M. Midgley, I. G. Jones, A. S. Purewal, and R. A. Skurray. 1992. Substrate specificity and energetics of antiseptic and disinfectant resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 74:259-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyon, B. R., and R. Skurray. 1987. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus: genetic basis. Microbiol. Rev. 51:88-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noguchi, N., M. Hase, M. Kitta, M. Sasatsu, K. Deguchi, and M. Kono. 1999. Antiseptic susceptibility and distribution of antiseptic-resistance genes in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 172:247-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paulsen, I. T., M. T. Gillespie, T. G. Littlejohn, O. Hanvivatvong, S.-J. Rowland, K. G. H. Dyke, and R. A. Skurray. 1994. Characterization of sin, a potential recombinase-encoding gene from Staphylococcus aureus. Gene 141:109-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paulsen, I. T., M. H. Brown, T. G. Littlejohn, B. A. Mitchell, and R. A. Skurray. 1996. Multidrug resistance proteins QacA and QacB from Staphylococcus aureus: membrane topology and identification of residues involved in substrate specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:3630-3635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paulsen, I. T., M. H. Brown, and R. A. Skurray. 1998. Characterization of the earliest known Staphylococcus aureus plasmid encoding a multidrug efflux system. J. Bacteriol. 180:3477-3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters, G. 1988. New considerations in the pathogenesis of coagulase-negative staphylococcal foreign body infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 21(Suppl. C):139-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rouch, D. A., D. S. Cram, D. DiBerardino, T. G. Littlejohn, and R. A. Skurray. 1990. Efflux-mediated antiseptic resistance gene qacA from Staphylococcus aureus: common ancestry with tetracycline- and sugar-transport proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 4:2051-2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rouch, D. A., and R. A. Skurray. 1989. IS257 from Staphylococcus aureus: member of an insertion sequence superfamily prevalent among gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Gene 76:195-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowland, S.-J., and K. G. H. Dyke. 1989. Characterization of the staphylococcal β-lactamase transposon Tn552. EMBO J. 8:2761-2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rowland, S.-J., and K. G. H. Dyke. 1990. Tn552, a novel transposable element from Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 4:961-975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 26.Schwarz, S., and M. Cardoso. 1991. Molecular cloning, purification, and properties of a plasmid-encoded chloramphenicol acetyltransferase from Staphylococcus haemolyticus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1277-1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skurray, R. A., D. A. Rouch, B. R. Lyon, M. T. Gillespie, J. M. Tennent, M. E. Byrne, L. J. Messerotti, and J. W. May. 1988. Multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus: genetics and evolution of epidemic Australian strains. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 21(Suppl. C):19-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skurray, R. A., and N. Firth. 1997. Molecular evolution of multiply-antibiotic-resistant staphylococci. Ciba Found. Symp. 207:167-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sohail, M., and K. G. H. Dyke. 1995. Sites for co-integration of large staphylococcal plasmids. Gene 162:63-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song, M. D., M. Wachi, M. Doi, F. Ishino, and M. Matsuhashi. 1987. Evolution of an inducible penicillin-target protein in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by gene fusion. FEBS Lett. 221:167-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sundheim, G., T. Hagtvedt, and R. Dainty. 1992. Resistance of meat associated staphylococci to a quaternary ammonium compound. Food Microbiol. 9:161-167. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabe, Y., A. Nakamura, T. Oguri, and J. Igari. 1998. Molecular characterization of epidemic multiresistant Staphylococcus haemolyticus isolates. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 32:177-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomayko, J. F., K. K. Zscheck, K. V. Singh, and B. E. Murray. 1996. Comparison of the β-lactamase gene cluster in clonally distinct strains of Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1170-1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, P.-J., S. J. Projan, and R. P. Novick. 1991. Nucleotide sequence of beta-lactamase regulatory genes from staphylococcal plasmid pI258. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:4000.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]