Abstract

Integron carriage by 36 epidemiologically unrelated Acinetobacter baumannii isolates collected over an 11-year period from patients in six different Italian hospitals was investigated. Sixteen type 1 integron-positive isolates (44%) were found, 13 of which carried the same array of cassettes, i.e., aacC1, orfX, orfX′, and aadA1a. As ribotype analysis of the isolates demonstrated a notable genetic diversity, horizontal transfer of the entire integron structure or ancient acquisition was hypothesized.

Clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii are frequently resistant to a wide range of antibiotics (1), but, compared to other gram-negative bacteria, little is known about the mechanism(s) by which these bacteria acquire resistance genes. Recently, a major role in the dissemination and evolution of antimicrobial resistance in many gram-negative organisms has been attributed to integrons. These are genetic elements consisting of a gene encoding an integrase (intI) flanked by a recombination site, attI, where mobile gene cassettes, mostly containing antibiotic-resistance determinants, can be inserted or excised by a site-specific recombination mechanism catalyzed by the integrase (16). Different integron types have been recognized on the basis of the sequence of the integrase gene.

The presence of type 1 and type 2 integrons has already been described in members of the genus Acinetobacter of both clinical (2, 6, 8, 9, 14, 17-19, 23) and environmental (13) origin. In particular, epidemic strains of A. baumannii (9) were found to carry these elements with high frequency.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the diffusion of type 1 integrons among clinical isolates of A. baumannii from our country and to carry out a molecular characterization of their gene cassette arrays.

To this purpose, 36 epidemiologically unrelated clinical isolates of A. baumannii collected over an 11-year period from six Italian hospital settings were selected (Table 1). The isolate AC-54/97 was already known to carry two type 1 integrons with variable regions of similar size, of which one (In42) had been previously characterized (17). All isolates were identified by amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis (4) and were subjected to ribotyping to investigate their genetic relatedness. Genomic DNA was extracted (5), digested by SalI, EcoRI, or ClaI (Roche Diagnostics SpA, Monza, Italy), and processed as described by Gerner-Smidt (7). Banding patterns were analyzed by GelComparII software (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium) with the Dice coefficient for evaluating similarity. Isolates were included in the same ribotype when their similarity coefficient was equal or superior to 0.85.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the isolates with or without type 1 integrons

| Ribotype group | Isolate | Hospitala and year of isolation | Source | Sizeb of 5′CS-3′CS amplicons | Size of hybridized bandc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 88A | P, 1990 | Pus | —d | — |

| 121A | P, 1989 | Blood | — | — | |

| II | 92A | P, 1990 | Blood | — | — |

| III | 27B | T, 1997 | Bronchial aspirate | — | — |

| IV | 7B | T, 1996 | Bronchial aspirate | 2.5 | 23.0 |

| V | 3B | T, 1996 | Bronchial aspirate | — | — |

| VI | 2B | T, 1996 | Urine | 2.5 | 23.0 |

| 24B | T, 1997 | Bronchial aspirate | 2.5 | 23.0 | |

| VII | 100B | T, 2000 | Urine | 2.5 | 18.0 |

| 108B | U, 2000 | Bronchial aspirate | 2.5 | 18.0 | |

| 109B | U, 2000 | Urine | 2.5 | 15.0 | |

| VIII | 105B | A, 1997 | Blood | — | — |

| IX | 56A | P, 1990 | Blood | — | — |

| X | 39A | P, 1990 | Blood | — | — |

| XI | 178A | R, 1993 | Urine | — | — |

| XII | 204A | T, 1995 | Pus | 0.8 | 15.0 |

| XIII | 176A | R, 1993 | Pus | — | — |

| XIV | 31B | T, 1997 | Blood | — | — |

| XV | 118A | P, 1989 | Bronchial aspirate | — | — |

| XVI | 124A | P, 1989 | Urine | — | — |

| 129A | P, 1990 | Wound | — | — | |

| XVII | 17A | P, 1990 | Pus | — | — |

| XVIII | AT1 | A, 1996 | Urine | — | — |

| XIX | AC-54/97e | V, 1997 | Bronchial aspirate | 2.5, 2.4 | 16.0, 5.0 |

| XX | F1 | A, 1995 | Blood | — | — |

| XXI | 132A | P, 1989 | Bronchial aspirate | — | — |

| XXII | 110B | U, 2000 | Pharingeal swab | — | — |

| XXIII | 179A | R, 1993 | Unknown | 2.5 | 11.0 |

| 133A | P, 1989 | Bronchial aspirate | 2.5 | 11.0 | |

| 60A | P, 1990 | Pus | 2.5 | 11.0 | |

| XXIV | 1B | T, 1996 | Urine | 2.5 | 10.5 |

| XXV | 23B | T, 1997 | Urine | 2.2 | 3.0 |

| 200A | T, 1995 | Urine | 2.2 | 3.0 | |

| XXVI | 141A | P, 1989 | Bronchial aspirate | — | — |

| XXVII | 24A | T, 1997 | Urine | 2.5 | 11.0 |

| XXVIII | 114A | P, 1989 | Pus | 2.5 | 12.5 |

A, Aviano; P, Padua; R, Rome; T, Trieste; U, Udine; V, Verona.

Size is expressed in kilobases.

The size (in kilobases) of the hybridization band obtained with the intI1 probe after digestion of genomic DNA with ClaI is shown.

Dashes indicate isolates that do not carry a type 1 integron.

This isolate carries two type 1 integrons.

By combining the results obtained with the three enzymes, all the isolates could be divided into 28 groups, each of them displaying a unique combination of ribotypes (Table 1). Results of this analysis overall indicated a notable genetic diversity of the selected isolates.

The presence of intI1-related sequences was initially investigated by dot blot hybridization of genomic DNAs with an intI1 digoxigenin-labeled probe that was prepared by amplification of a 250-bp segment of the intI1 gene from plasmid R46 (3, 16) with primers Int2F (11) and Int2R (5′-TGGCTTCAGGAGATCGGA-3′ [this work]).

A positive hybridization signal was obtained with 16 (44%) isolates. The majority of them (12 of 16) were collected during the second half of the considered period (from 1995 on), thus suggesting an increase in the prevalence of integron-positive A. baumannii over time (Table 1).

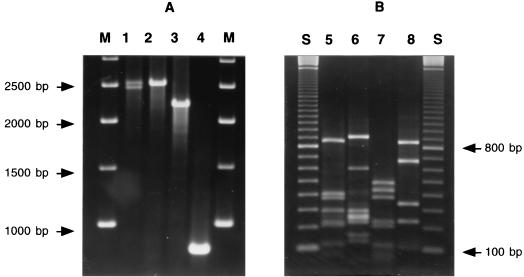

To detect inserted gene cassettes, the variable regions of type 1 integrons, carried by the 16 intI1-positive isolates, were amplified with primers 5′CS and 3′CS, which annealed with the DNA regions flanking the recombination site attI (10) by using the Expand long template PCR system (Roche Diagnostics SpA). A single amplification product of approximately 2.5 kb was obtained from 13 isolates belonging to 10 different ribotype groups; among them, AC-54/97 also gave a second, slightly smaller amplification product, which corresponded to that of the previously characterized In42 (17) (Fig. 1A, Table 1, and data not shown). Of the remaining intI1-positive isolates, two (of an identical ribotype group) gave an amplification product of approximately 2.2 kb while one yielded an amplification product of approximately 0.8 kb (Fig. 1A and Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Amplification products obtained from the variable regions of type 1 integrons (A) and results of their restriction analysis (B). Panel A shows amplicons obtained with primers 5′CS and 3′CS from representative isolates. Lane 1, isolate AC-54/97 (amplicons of 2.5 and 2.4 kb); lane 2, isolate 7B (amplicon of 2.5 kb); lane 3, isolate 200A (amplicon of 2.2 kb); lane 4, isolate 204A (amplicon of 0.8 kb); M, kilobase pair ladder (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Milan, Italy). Panel B shows digestion with AluI (lanes 5 and 7) or MspI (lanes 6 and 8) of a representative amplicon of 2.5 kb (isolate 7B [lanes 5 and 6]) or 2.2 kb (isolate 200A [lanes 7 and 8]). DNA fragments were separated on a 2% agarose gel. Lane S, 100-bp ladder (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

The sequence similarity among the 2.5-kb amplicons obtained from the 13 isolates was investigated by restriction analysis. For AC-54/97, which yielded two amplicons, the restriction profiles of the 2.5-kb amplicon were generated from a product obtained by using pMLR54G, a recombinant plasmid that carries a cloned copy of the corresponding integron, as a template (17). All amplicons gave identical restriction patterns following digestion with MspI or with AluI and, with either enzyme, the sum of the sizes of the restriction fragments was consistent with the size of the undigested amplicon (Fig. 1B and data not shown). These results indicated that the variable regions of the integrons carried by the above isolates were identical or very similar.

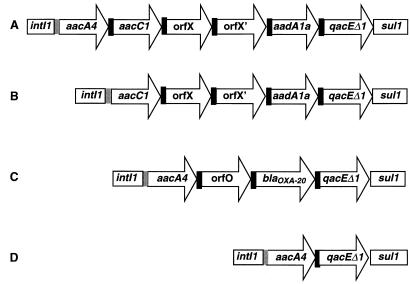

The nucleotide sequence of the cloned integron from AC-54/97, carried by pMLR54G, was determined with crude PCR products as previously described (17). Sequence analysis was carried out by the BLAST program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and revealed the presence of four gene cassettes (Fig. 2), the first of which contains an aacC1 determinant encoding an AAC(3)-Ia aminoglycoside acetyltransferase (20). This is followed by two open reading frames (ORFs) coding for unknown products that are carried by two cassettes, in the first of which the ORF overlaps almost entirely with the attC site. The fourth cassette contains an aadA1a determinant encoding an AAD(3")-Ia aminoglycoside adenyltransferase (20). Identical results were obtained from direct sequencing of the amplicon obtained from isolate 7B. Interestingly, the same array of gene cassettes has been described also as part of a larger variable region contained in type 1 integrons from Klebsiella oxytoca (15), Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium (21, 24), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (unpublished EMBL/GenBank accession no. AF282595). However, in all those cases, the variable region also contained an additional cassette, with the aacA4 determinant in the first position (Fig. 2). An apparently truncated version of the same structure, containing only part of the third and fourth cassette, was recently reported to be present in A. baumannii from South Africa (B. G. Elisha and R. Thomas, 5th Int. Symp. Biol. Acinetobacter, p.14, 2000).

FIG. 2.

Structure of the variable region of type 1 integrons detected in this study in A. baumannii and comparison with that of a similar integron previously characterized from other species. Coding sequences are indicated by arrows with the corresponding names; the attC and attI sites are indicated by black and gray filled rectangles, respectively. (A) Structure of the integron found in IncL/M plasmids from K. oxytoca (15) and S. enterica serotype Typhimurium (21, 24). The same sequence was also deposited in EMBL/GenBank under accession no. AF282595 (unpublished). (B through D) Amplicons of 2.5, 2.2, and 0.8 kb, respectively, found in this work.

Restriction analysis with MspI and AluI yielded identical patterns, with the 2.2-kb amplicons obtained from isolates 200A and 23B, and, with either enzyme, the sum of the restriction fragments was consistent with the size of the undigested amplicon (Fig. 1B and data not shown).

Direct sequencing of the amplicon from isolate 200A revealed the presence of three gene cassettes (Fig. 2), the first containing an aacA4 allele encoding an AAC(6′)-Ib aminoglycoside acetyltransferase (20), the second containing an ORF coding for a yet undetermined product named orfO and found also in other integrons (14), and the third containing the blaOXA-20 gene (12).

The same cassette array was found also in type 1 integrons of clinical A. baumannii isolates from France (14) and Spain (unpublished EMBL/GenBank accession no. AY007784,). In the latter case, however, the blaOXA gene, named blaOXA-31, exhibits some differences and, since the deposited sequence terminates at the end of the third cassette, the presence of additional cassettes cannot be ruled out.

Direct sequencing of the 0.8-kb amplicon obtained from isolate 204A revealed the presence of a single gene cassette that contained an aacA4 allele (Fig. 2) encoding an aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase AAC(6′)-Ib which was identical to that found in the integrons from isolates 200A and 23B.

To investigate the location of the integrons found in this study, Southern blot analysis of the genomic DNAs, either undigested or after digestion with ClaI (which does not cut into intI1), was carried out with the intI1 probe. Results of these experiments revealed the following. (i) Although one or more plasmids were clearly visible after the electrophoretic separation of the genomic DNA of many isolates, in all of them a positive hybridization signal was detectable only in correspondence with undigested chromosomal DNA. On the contrary, the hybridization signal of the control strain Escherichia coli J53/R46 was detected in correspondence to the migration distance of plasmid R46 (data not shown). (ii) In all isolates, except AC-54/97, a single hybridization band of variable size (Table 1) was observed after digestion with ClaI, suggesting the presence of a single copy of the integrase gene. AC-54/97 yielded two bands, in agreement with previous data indicating the presence of two integrons (17). (iii) Hybridization bands of isolates belonging to the same ribotype group generally had the same size, thus confirming the genetic relatedness of the isolates within the group; in contrast, isolates belonging to different groups often had different band sizes (Table 1). Overall, the results obtained from Southern blot analysis are suggestive of the presence of a single integron in all isolates except AC-54/97, and the most likely location of the integrons appears to be the chromosome. The heterogeneity of the hybridization bands obtained following the restriction of genomic DNA with ClaI renders unlikely the hypothesis that the integrons are located on a plasmid comigrating with the chromosome in all isolates.

In conclusion, our study confirms the high prevalence of integrons found in A. baumannii by other authors (14, 19) and indicates that integron structures with the same variable region can be retrieved from genotypically distinguishable strains. In particular, a remarkable number of genotypically different isolates carry a type 1 integron with the same variable region, yielding an amplicon of 2.5 kb. This integron appears to be widely diffused, being present in isolates collected over a long period of time from five of the six Italian hospitals included in this study (Table 1). A similar finding suggests that horizontal transfer of the entire integron structure could have taken place on different occasions and that, once acquired, the integron was remarkably stable. Strain differentiation may also have occurred after integron acquisition. Interestingly, a very similar integron structure was previously described in Enterobacteriaceae (15, 21, 24), suggesting interspecies transfer. As the widely diffused integron described in this study is apparently not carried by a plasmid, we do not know at present how it is transferred from one strain to another. Natural transformation, which is known to occur in acinetobacters (22), could have played a relevant role in this instance.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences reported in this work have been assigned the following EMBL/GenBank accession numbers: isolate 200A, AJ319747; isolate 204A, AJ313334; isolate AC-54/97, AJ310480.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Giuseppe Satta, who donated some of the isolates. We also thank P. De Paoli (Aviano), R. Fontana (Verona), and P. Lanzafame (Udine) for the gift of some isolates and D. Pirulli for partially sequencing isolate 7B.

This work was supported by grants from the Italian MIUR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergogne-Bérézin, E., and K. J. Towner. 1996. Acinetobacter spp. as nosocomial pathogens: microbiological, clinical, and epidemiological features. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:148-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu, Y.-W., M. Afzal-Shah, E. T. S. Houang, M.-F. I. Palepou, D. J. Lyon, N. Woodford, and D. M. Livermore. 2001. IMP-4, a novel metallo-β-lactamase from nosocomial Acinetobacter spp. collected in Hong Kong between 1994 and 1998. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:710-714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Couturier, M., F. Bex, P. L. Bergquist, and W. K. Maas. 1988. Identification and classification of bacterial plasmids. Microbiol. Rev. 52:375-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dijkshoorn, L., B. van Harsselaar, I. Tjernberg, P. J. M. Bouvet, and M. Vaneechoutte. 1998. Evaluation of amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis for identification of Acinetobacter genomic species. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21:33-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dolzani, L., E. Tonin, C. Lagatolla, L. Prandin, and C. Monti-Bragadin. 1995. Identification of Acinetobacter isolates in the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex by restriction analysis of the 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer sequences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1108-1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallego, L., and K. J. Towner. 2001. Carriage of class I integrons and antibiotic resistance in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii from northern Spain. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:71-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerner-Smidt, P. 1992. Ribotyping of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:2680-2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez, G., K. Sossa, H. Bello, M. Dominguez, S. Mella, and R. Zemelman. 1998. Presence of integrons in isolates of different biotypes of Acinetobacter baumannii from Chilean hospitals. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 161:125-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koeleman, J. G. M., J. Stoof, M. W. Van der Bijl, C. M. J. E. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, and P. H. M. Savelkoul. 2001. Identification of epidemic strains of Acinetobacter baumannii by integrase gene PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lévesque, C., L. Piché, C. Larose, and P. H. Roy. 1995. PCR mapping of integrons reveals several novel combinations of resistance genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:185-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez-Freijo, P., A. C. Fluit, F.-J. Schmitz, V. S. C. Grek, J. Verhoef, and M. E. Jones. 1998. Class I integrons in gram-negative isolates from different European hospitals and association with decreased susceptibility to multiple antibiotic compounds. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 42:689-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naas, T., W. Sougakoff, A. Casetta, and P. Nordmann. 1998. Molecular characterization of OXA-20, a novel class D β-lactamase, and its integron from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2074-2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen, A., L. Guardabassi, A. Dalsgaard, and J. E. Olsen. 2000. Class I integrons containing a dhfrI trimethoprim resistance gene cassette in aquatic Acinetobacter spp. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 182:73-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ploy, M.-C., F. Denis, P. Courvalin, and T. Lambert. 2000. Molecular characterization of integrons in Acinetobacter baumannii: description of a hybrid class 2 integron. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2684-2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Preston, K. E., C. C. A. Radomski, and R. A. Venezia. 1999. The cassettes and 3′ conserved segment of an integron from Klebsiella oxytoca plasmid pACM1. Plasmid 42:104-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Recchia, G. D., and R. M. Hall. 1995. Gene cassettes: a new class of mobile element. Microbiology 141:3015-3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riccio, M. L., N. Franceschini, L. Boschi, B. Caravelli, G. Cornaglia, R. Fontana, G. Amicosante, and G. M. Rossolini. 2000. Characterization of the metallo-β-lactamase determinant of Acinetobacter baumannii AC-54/97 reveals the existence of blaIMP allelic variants carried by gene cassettes of different phylogeny. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1229-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seward, R. J., T. Lambert, and K. J. Towner. 1998. Molecular epidemiology of aminoglycoside resistance in Acinetobacter spp. J. Med. Microbiol. 47:455-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seward, R. J., and K. J. Towner. 1999. Detection of integrons in worldwide nosocomial isolates of Acinetobacter spp. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 5:308-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaw, K. J., P. N. Rather, R. S. Hare, and G. H. Miller. 1993. Molecular genetics of aminoglycoside resistance genes and familial relationships of the aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes. Microbiol. Rev. 57:138-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tosini, F., P. Visca, I. Luzzi, A. M. Dionisi, C. Pezzella, A. Petrucca, and A. Carattoli. 1998. Class I integron-borne multiple-antibiotic resistance carried by IncFI and IncL/M plasmids in Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:3053-3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Towner, K. J. 1996. Biology of Acinetobacter spp., p.13-36. In E. Bergogne-Bérézin, M. L. Joly-Guillou, and K. J. Towner (ed.), Acinetobacter: microbiology, epidemiology, infections, management. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 23.Vila, J., M. Navia, J. Ruiz, and C. Casals. 1997. Cloning and nucleotide sequence analysis of a gene encoding an OXA-derived β-lactamase in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2757-2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villa, L., C. Pezzella, F. Tosini, P. Visca, A. Petrucca, and A. Carattoli. 2000. Multiple-antibiotic resistance mediated by structurally related IncL/M plasmids carrying an extended-spectrum β-lactamase gene and a class 1 integron. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2911-2914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]