Abstract

Telomere-specific clones are a valuable resource for the characterization of chromosomal rearrangements. We previously reported a first-generation set of human telomere probes consisting of 34 genomic clones, which were a known distance from the end of the chromosome (∼300 kb), and 7 clones corresponding to the most distal markers on the integrated genetic/physical map (1p, 5p, 6p, 9p, 12p, 15q, and 20q). Subsequently, this resource has been optimized and completed: the size of the genomic clones has been expanded to a target size of 100–200 kb, which is optimal for use in genome-scanning methodologies, and additional probes for the remaining seven telomeres have been identified. For each clone we give an associated mapped sequence-tagged site and provide distances from the telomere estimated using a combination of fiberFISH, interphase FISH, sequence analysis, and radiation-hybrid mapping. This updated set of telomeric clones is an invaluable resource for clinical diagnosis and represents an important contribution to genetic and physical mapping efforts aimed at telomeric regions.

Introduction

The telomeric regions of human chromosomes are enriched for CpG islands and genes and are believed to have the highest gene density in the entire genome (Saccone et al. 1992). Characterization of telomeric regions is important for our understanding of the relationship between chromosome structure and function (Flint et al. 1997a) and because chromosomal rearrangements involving telomeres result in a number of clinical conditions, including mental retardation (Knight et al. 1999; Holinski-Feder et al. 2000), recurrent miscarriage and hematological malignancies (Tosi et al. 1999). The ability to identify each chromosome end also aids in the characterization of known chromosomal abnormalities (Ning et al. 1996; Horsley et al. 1998). However, telomeric rearrangements are a challenge to detect using conventional clinical cytogenetics methods, since most terminal bands are G-band negative. Thus, alternative methodologies, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) array–based approaches, are required for high-resolution screening of telomeric regions. Furthermore, for mapping and sequencing efforts, it is imperative that the location of the telomere be known so that maps can be anchored and telomeric closure achieved.

The size and complexity of telomeric regions has made them extremely difficult to analyze at a molecular level. The high degree of sequence similarity between subtelomeric domains on different chromosomes, the presence of genes in subtelomeric DNA, and chromosomal rearrangements occurring within subtelomeric repeats all have important implications for screening strategies aimed toward assessment of subtelomeric integrity (Brown et al. 1990; Rouyer et al. 1990; Wilkie et al. 1991; Flint et al. 1997b; Monfouilloux et al. 1998; Trask et al. 1998). If chromosome unique (and, hence, more centromeric) sequences are used for screening, then rearrangements telomeric to the probe will be missed. If repetitive subtelomeric DNA sequences are used, then the exact chromosomal origin of the detected DNA will be uncertain. A practical solution to this problem is to use unique sequence probes, accepting that a small proportion of rearrangements may be missed.

The discovery that telomeres from human chromosomes can be cloned by functional complementation in yeast enabled the molecular characterization of subtelomeric repetitive and chromosome unique DNA (Brown et al. 1989; Cross et al. 1989; Riethman et al. 1989; Bates et al. 1990). When yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) vectors with only one functional telomere are ligated to human genomic DNA, clones survive in the yeast host cells if they are stabilized by the presence of a second telomere derived from the human genomic DNA (“half-YACs”) (Xiang et al. 1999). Characterization of half-YAC libraries produced in this way has resulted in the development of a valuable set of molecular resources for analyzing most, if not all, chromosome ends (National Institutes of Health et al. 1996; Rosenberg et al. 1997). As part of an international collaboration to identify a complete set of human telomere probes for use in FISH assays, we previously reported a first generation set of 41 clones consisting of 34 telomere clones that were a known distance from the end of each chromosome and 7 clones corresponding to the distal marker from the integrated map (1p, 5p, 6p, 9p, 12p, 15q, 20q) (National Institutes of Health et al. 1996). The total number of clones targeted for the complete set was 41 rather than 48, since no efforts were made to identify clones representing the short arm of the acrocentric chromosomes, and clones corresponding to the X and Y pseudoautosomal regions are shared. Most of the clones in the initial set were cosmid clones (35–40 kb), which are adequate in FISH experiments as a single probe, but frequently do not produce a sufficiently robust signal in multicolor experiments. In addition, some clones showed cross-hybridization to other chromosome regions by FISH. Seven chromosome arms were previously represented by distal markers, which were an unknown distance from the end of the chromosome. Subsequently, we have shown that clones corresponding to such distal markers can be as far as 1 Mb from the telomere, thus increasing the possibility that smaller telomeric rearrangements may be missed (Lese et al. 1999).

For these reasons, and to contribute to genome mapping and sequencing efforts, the first-generation telomere set has been refined. All cosmid probes have been replaced with more robust PAC, P1, or BAC clones and probes previously derived from the most distal markers on the Whitehead/MIT map have been converted into clones of known distance from the end of the chromosome. We describe here the isolation and detailed characterization of this second-generation set of human telomere clones.

Material and Methods

Isolation of Second Generation Set of Telomere-Specific Clones

PCR screening was carried out using sequence-tagged sites (STSs) developed from distal markers, telomeric sequence information, half-YAC vector-insert junction sequences or end sequences from telomeric clones. The methods for identifying half-YAC clones, isolating vector-insert junction fragments and obtaining sequence information have been described elsewhere (Cross et al. 1989; Riethman et al. 1989; Negorev et al. 1994), as have the method employed to make STSs from bacterial clones (Rosenberg et al. 1997). The software package Primer 3 was utilized to create primers from sequence information (see Electronic-Database Information). Primer pairs were tested and optimized on a monochromosomal hybrid panel (available from the Coriell Institute for Medical Research or from the United Kingdom Human Genome Mapping Project resource center) to identify conditions that produce chromosome specific PCR amplification for screening purposes. Standard PCR conditions with 1.5 mM MgCl2 and a 55°C annealing temperature were used for all newly developed STSs.

A (TTAGGG)n telomere probe and the STSs were used to screen PAC and BAC libraries (PAC library from Genome Systems and the Bacpac Web site [RPCI-1]; BAC libraries from Genome Systems and Research Genetics [CITB-978SK-B and CITB-HSP-C]). The letters RG or GS preceding a clone address identify that clone as being isolated from the Research Genetics library and the Genome Systems library, respectively. The presence of an STS in positive clones was confirmed by PCR amplification of the STS from a single colony of the PAC, P1, or BAC clone. A second hybridization screen confirmed (TTAGGG)n positive clones.

BAC End Sequencing

BAC DNA was isolated using an automated nucleic-acid isolation system (AutoGen 740, Integrated Separation Systems) and purified with Microcon 100 columns (Amicon). One microgram of BAC DNA and 40 pmol of T7 and SP6 primers were used for sequencing with the ABI PrismTM Big-Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (PE Applied Biosystems). The sequences of the T7 and SP6 primers and the sequencing reaction times have been previously reported (Matsumoto et al. 1997). Sequence analysis was completed on an ABI 377 automated DNA sequencer.

FISH Characterization/Testing of New Telomere Probes

DNA was isolated for FISH analysis using an Autogen 740 or a standard alkaline-lysis protocol (Sambrook et al. 1989). FISH analysis was carried out on normal metaphases cultured from peripheral blood to test each new probe identified. Probe and slide preparation, DNA hybridization, and analysis were carried out using methods described elsewhere (Buckle and Rack 1993; Chong et al. 1997). At least 10 cells were analyzed using direct microscopic visualization and digital-imaging analysis to verify probe location and chromosome specificity. Inverted DAPI staining was used to obtain a G-banded pattern for chromosome identification. A probe was characterized as unique only if the signal was telomere specific (i.e., no cross-hybridization to any other chromosomes), both directly visualized at the microscope and on the individual fluorochrome raw image. Probes were tested for common polymorphisms by analyzing the size and intensity of the FISH signals on at least five unrelated individuals.

Interphase FISH Analysis

Interphase distance measurements were carried out as described elsewhere (Lese et al. 1999). Briefly, dual-color FISH was used for measuring genomic distances between differentially labeled clones in interphase nuclei from G0 fibroblast cells. The distances measured were from the telomere clone of interest to a subtelomeric clone known to be contained within the relevant half-YAC. Actual genomic distances were calculated using the measure length command contained in the IP Lab Spectrum software package (version 3, Signal Analytics); the measure length command was calibrated using images from a Zeiss stage micrometer. Genomic distances were derived from a calibration curve that was produced in our laboratory (Lese et al. 1999). For each telomere, 50–100 interphase distances were measured.

For the telomeric region of 1p, interphase FISH mapping was performed using three-color ordering. FISH was carried out as described above. Probes were labeled with Spectrum Orange, biotin, or digoxigenin, and detection was carried out using avidin-Cy5 (for biotin-labeled probes) and anti-digoxigenin-FITC (for digoxigenin-labeled probes). Spectrum Orange–labeled nucleotides are directly incorporated into the DNA, and therefore antibody detection of was not necessary. The three labeled DNA probes were hybridized simultaneously to interphase cells from a chromosome 1 monochromosomal hybrid cell line (GM13139A, Coriell Institute for Medical Research). Images were captured using ViewPoint software (Vysis). Only cells that showed three hybridization signals in a linear formation were used for clone ordering. At least 30 cells were scored to determine the order that occurred with the greatest frequency.

Sequence Analysis

M13 bacteriophage libraries were created from the 5p, 6p, 12p, and 20q (TTAGGG)n positive PACS and were screened by hybridization and sequenced as described elsewhere (Flint et al. 1997a, 1998). After Alu and other repetitive DNA were excluded, the sequences obtained from the clones were screened against dbEST and EMBL with BLASTN, and against a nonredundant compilation of Swissprot, PIR and wormpep (Caenorhabditis elegans genes) with BLASTX. The BLAST outputs were filtered using MSPcrunch (Sonnhammer and Durbin 1994), requiring ⩾90% identity for dbEST and EMBL matches. BLASTN/MSPcrunch also was used to identify sequence matches between telomeres.

Radiation Hybrid (RH) Mapping

RH mapping makes use of a panel of somatic cell hybrids, with each cell line containing a random set of fragments of irradiated human genomic DNA in a hamster background. To obtain mapping data, our STSs were screened by PCR against the Genebridge4 radiation-hybrid screening panel at the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research/MIT Center for Genome Research. The STSs submitted for RH mapping are listed intable 1table 1. The PCR results were recorded as RH vectors of 1's and 0's, indicating the presence or absence, respectively, of the STS in each hybrid. The most likely chromosomal assignments and placements of the STSs were determined from the vector data by computational analysis. Two markers were considered to be linked if they had vectors of statistically significant similarity and if a measure of their separation was obtained from the analysis of the degree of difference between the two vectors. Map distances were calculated in units of centiRays (cR) (referring to the X-ray dosage used to construct the RH panel).

Table 1.

Second-Generation Telomere Clones and Their Location

| Telomere | Clone ID | CloneType | MaximumPhysicalDistancefromTelomere(kb) | Method | Fiber-FISH (kb)a | RHMapping(cR)b | Marker |

| 1p | GS-62-L8 | PAC | 200 | Interphase mapping from subtelomeric sequences | 7.69 tel | 1PTEL06 | |

| GS-232-B23 | BAC | 200 | Interphase mapping from subtelomeric sequences | CEB108/T7 | |||

| 1q | GS-160-H23 | PAC | 80 | Contig | <50 | 1QTEL19 | |

| GS-167-K11 | BAC | 270 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 1QTEL10, 1QTEL19, VIJ-YRM2123 | |||

| 2p | GS-892-G20 | PAC | 330 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 2PTEL27 | ||

| GS-8-L3 | BAC | 330 | RARE from YAC end sequence | VIJ-YRM2052 | |||

| 2q | GS-1011-O17 | PAC | 240 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 2QTEL47 | ||

| RG-172-I13 | BAC | 240 | RARE from YAC end sequence | VIJ-YRM2112 | |||

| 3p | GS-1186-B18 | PAC | 450 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 150–250 | 3PTEL25 | |

| RG-228-K22 | BAC | 450 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 3PTEL25 | |||

| 3q | 196-F4 | PAC | 450 | YAC clone size | 3QTEL06 | ||

| GS-56-H22 | BAC | 450 | YAC clone size | 3QTEL05 | |||

| 4p | GS-36-P21 | PAC | 73 | Sequence: Z95704 | 80–100 | 4PTEL04 | |

| GS-118-B13 | BAC | 101 | Sequence: Z95704; walk from 4PTEL01 | GS10K2/T7 | |||

| 4q | GS-963-K6 | PAC | 275–500 | Contig (vanGeel et al. 1999) | 2.9 tel | 4QTEL11 | |

| GS-31-J3 | BAC | 300–700c | Interphase distance from 4QTEL11 | AFMA224XH1 | |||

| 5p | GS-189-N21 | PAC | Unknown | 16.2 cen | 5PTEL48 | ||

| GS-24-H17 | BAC | Unknown | Distal marker of 5p contig | C84C11/T3 | |||

| 5q | GS-240-G13 | PAC | 245 | YAC clone size | 5QTEL70 | ||

| 6p | GS-62-I11 | PAC | 300 | Fiber FISH | <300 | 19.3 cen | 6PTEL48 |

| GS-196-I5 | BAC | 300 | 6PTEL48 | ||||

| 6q | GS-57-H24 | PAC | 280 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 6QTEL54 | ||

| 7p | GS-164-D18 | PAC | 255 | YAC clone size | ∼130 | 5.76 cen | 7PTEL03, VIJ-YRM2185 |

| 7q | GS-3K-23 | PAC | 7 | Sequence: AF027390 | 7QTEL20, VIJ-YRM2000 | ||

| 8p | GS-580-L5d | PAC | 250 | YAC clone size | NP | 8PTEL91 | |

| GS-77-L23 | BAC | 250–450c | Interphase distance from 8PTEL91 | AFM197XG5 | |||

| 8q | GS-489-D14 | PAC | 170 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 8QTEL11 | ||

| GS-261-I1 | BAC | 170 | RARE from YAC end sequence | VIJ-YRM2053 | |||

| 9p | GS-43-N6 | PAC | 600 | YAC clone size | <600 | 13.9 tel | 9PTEL30 |

| RG-41-L13 | BAC | 190 | YAC clone size | 305J7-T7 | |||

| 9q | GS-112-N13d | PAC | 65 | YAC clone size | NP | 9QTEL33 | |

| GS-135-I17 | BAC | 65 | YAC clone size | VIJ-YRM2241 | |||

| 10p | GS-306-F7 | PAC | 320 | YAC clone size | ∼100 | 10PTEL45 | |

| GS-23-B11 | BAC | 320 | YAC clone size | 10PTEL006 | |||

| 10q | GS-137-E24 | PAC | 270 | YAC clone size | ∼100 | 10QTEL24 | |

| GS-261-B16 | BAC | 270 | YAC clone size | 10QTEL24 | |||

| 11p | GS-908-H22d | PAC | 125 | YAC clone size | NP | 11PTEL03 | |

| GS-44-H16 | PAC | 125 | YAC clone size | VIJ-YRM2209 | |||

| 11q | GS-770-G7d | PAC | 65 | YAC clone size | NP | 11QTEL38 | |

| GS-26-N8 | PAC | 65 | YAC clone size | VIJ-YRM2072 | |||

| 12p | GS-496-A11d | PAC | Unknown | TTAGGG clone | NP | 27.8 cen | 12PTEL27 |

| GS-8-M16d | BAC | 100 | YAC clone size | TYAC-14 | |||

| GS-124-K20 | BAC | 100 | YAC clone size | 8M16/SP6 | |||

| 12q | GS-221-K18 | PAC | 190 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 100/600e | 12QTEL87, VIJ-YRM2196 | |

| 13q | GS-163-C9 | PAC | 170 | RARE from YAC end sequence | <20 | 13QTEL56 | |

| GS-1-L16 | PAC | 170 | RARE from YAC end sequence | VIJ-YRM2002 | |||

| 14q | GS-820-M16 | PAC | 200 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 14QTEL01 | ||

| GS-200-D12 | BAC | 200 | RARE from YAC end sequence | VIJ-YRM2006 | |||

| 15q | GS-124-05d | PAC | 300c | Interphase mapping from 15q YAC | NP | 24.46 tel | 15QTEL56 |

| GS-154-P1 | PAC | 300c | Interphase mapping from 15q YAC | WI-5214 | |||

| 16p | GS-121-I4 | PAC | 160 | Sequence: Z84721 | 16PTEL05 | ||

| RG-191-K2 | BAC | 160 | Sequence: Z84721 | 16PTEL05 | |||

| 16q | GS-240-G10 | PAC | 200 | YAC clone size | 17.91 tel | 16QTEL48 | |

| GS-191-P24 | PAC | 200 | YAC clone size | 16QTEL13 | |||

| 17p | GS-202-L17d | PAC | 60 | Contig (Xiang et al. 1999) | 30/100e | 17PTEL80 | |

| GS-68-F18 | BAC | 100–200 | Walk from 17PTEL80 | 282M15/SP6 | |||

| 17q | GS-362-K4d | PAC | 90 | YAC clone size | NP | 17QTEL13 | |

| GS-50-C4 | BAC | 100–300 | Interphase distance from 17QTEL13 | AFM217YD10 | |||

| 18p | GS-52-M11 | P1 | 220 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 18PTEL02 | ||

| GS-74-G18 | BAC | 220 | RARE from YAC end sequence | VIJ-YRM2102 | |||

| 18q | GS-964-M9 | PAC | 290 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 18QTEL11 | ||

| GS-75-F20 | BAC | 290 | RARE from YAC end sequence | VIJ-YRM2050 | |||

| 19p | GS-546-C11 | PAC | 250–500 | LLNL chromosome 19 contig | NP | 16.13 tel | 19PTEL29 |

| RG-129-F16 | BAC | 250–500 | LLNL chromosome 19 contig | 129F16/SP6 | |||

| 19q | GS-48-O23 | PAC | 250–500 | LLNL chromosome 19 contig | 11.65 tel | 19QTEL12 | |

| GS-325-I23 | BAC | 250–500 | LLNL chromosome 19 contig | D19S238E | |||

| 20p | GS-1061-L1 | PAC | 180 | YAC clone size | 20PTHY33 | ||

| GS-82-O2 | PAC | 180 | YAC clone size | 20PTEL18 | |||

| 20q | GS-81-F12d | PAC | 50 | Fiber FISH | <50 | 28.2 tel | 20QTEL14 |

| 21q | GS-63-H24 | PAC | 175 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 21QTEL07 | ||

| GS-2-H14d | P1 | 175 | RARE from YAC end sequence | VIJ-YRM2029 | |||

| 22q | GS-99-K24d | PAC | 120 | Sequence: (Dunham et al. 1999) | 150–200 | 12.6 tel | 22QTEL31 |

| GS-3018-K1 | BAC | 155 | Sequence: (Dunham et al. 1999) | 3018K1/T7 | |||

| XpYp | GS-98-C4 | PAC | 490 | STS map (Nagaraja et al. 1997) | DXYS28 | ||

| GS-839-D20 | BAC | 160 | STS map (Nagaraja et al. 1997) | DXYS129 | |||

| XqYq | GS-225-F6 | BAC | 100 | CDY16C07 | |||

| Xq | GS-202-M24 | PAC | 500 | STS map (Nagaraja et al. 1997) | DXS7059 |

NP = not possible, because of cross-hybridization.

cen = centromeric; tel = telomeric.

The distance given is the sum of the size of the relevant half-YAC and the estimated interphase FISH distance between the BAC clone and a subtelomeric clone known to be contained within the half-YAC.

Cross-hybridization visible by FISH; see table 3 for details.

Fiber-FISH indicates a size polymorphism.

FiberFISH

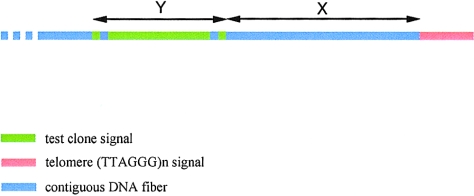

PAC DNAs were nick-translation labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim) according to a standard protocol (Buckle and Rack 1993). To obtain the (TTAGGG)n fluorescent probe, PCR was carried out in a 40-ml reaction containing 1 ng telomere probe (a plasmid containing 3 kb of canonical telomere sequence, kindly supplied by Dr. N. Royle), 1 mM oligonucleotide Tel1 (5′-TTAGGGTTAGGGTTAGGG-3′), 1 mM oligonucleotide Tel2 (5′-CTAACCCTAACCCTAACC-3′), 1 × PCR Buffer (10 × PCR +Mg stock, Boehringer Mannheim), 1 × dNTPs (100 × DNA polymerization mix, Pharmacia Biotech) and 4 U Taq polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim). The PCR conditions were 30 cycles of 96°C for 40 s, 65°C for 40 s, 70°C for 5 min. The products (300 bp–12 kb in size) were then purified using the Wizard PCR kit (Promega) and nick-translation labeled with biotin-11-dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim). For each slide to be hybridized, ∼60 ng labeled telomere probe and ∼60 ng labeled PAC DNA were vacuum dried with 15–20 mg COT-1 (Gibco-BRL), and the pellet was resuspended in 45 ml hybridization solution (65% formamide [Fluka], 1 × SSC , 10% dextran sulfate [molecular weight 500,000; BDH, Inc.]). DNA fibers were prepared on poly-L-lysine coated slides (Sigma), as described by Heiskanen et al. (1996). The prepared slides were washed in 2 × SSC for 5 min and then were dehydrated through a 70%, 90%, and 100% ethanol series for 3–5 min at each percentage. The slides were equilibrated on a 37°C hotblock, and the probe solution was added and was sealed in place with a 22-mm × 64-mm cover slip. The DNA and probes were denatured together on a 75°C hotblock for 1 min 35 s, and the slides were hybridized overnight in a slide box floating in an uncovered 37°C water bath. The slides were washed, and the probes were detected by fluorescently conjugated antibodies, as described elsewhere (Knight et al. 1997). The hybridized DNA fibers were viewed using an Olympus BX60 microscope, as described elsewhere (Knight et al. 1997). The (TTAGGG)n signals fluoresced red, and the PAC clone signals fluoresced green. The distances between the red and green signals were estimated on a linear scale, with the average size of a PAC being taken as ∼100 kb. To achieve this, the fiberFISH images were saved in TIFF format. They were then accessed using Adobe Photoshop 4.0, and two measurements were recorded in mm: Y, the length of the PAC signal (beginning to end of the green signal, including closely interrupted signals, but excluding any small isolated signals considered to be nonspecific); and X, the intervening distance between the green signal and the red signal. The distance from the most distal end of the PAC to the most proximal telomeric sequence was calculated in kb as 100(X/Y). A schematic representation of the derivation of fiberFISH distances is given in figure 3. To confirm the validity of the fiberFISH results, two control hybridizations using the 4p cosmid, B31, and the 16p cosmid, cGG4, which are known to be ∼70 kb and 81 kb, respectively, from their cognate telomeres (Flint et al. 1997a), were also performed.

Figure 3.

Diagram showing the derivation of fiberFISH distances. The fiberFISH distance in kb (D) between the test clone signal and the telomere (TTAGGGital)n signal is given by D=Z(X/Y), where Z is the known size of the test clone in kb, Y is the length of the test-clone signal in mm and X is the distance between the test-clone signal and the telomere signal in mm.

RecA-Assisted Restriction Endonuclease (RARE) cleavage

RARE cleavage is a method used to perform sequence-specific cleavage of genomic DNA (Ferrin and Camarini-Otero 1991, 1994). It exploits the ability of the RecA protein of Escherichia coli to pair an oligonucleotide to its homologous sequence in duplex DNA and to form a three-stranded complex. The duplex in the complex is protected from methylation by site-specific DNA methyltransferases. Thus, when the three-stranded complex is exposed to site-specific DNA methyltransferases and the oligonucleotide and RecA protein are subsequently removed, the only sites which can be cleaved by methylation sensitive restriction endonucleases are the sites in the duplex which were previously protected from methylation. The major application of the RARE cleavage technique is in constructing long-range physical maps of genomic DNA, but it has also been adapted so that distances between a particular restriction endonuclease site and the respective telomere can be determined (Ferrin and Camerini-Otero 1994; Riethman et al. 1997).

The RARE results given intable 1table 1 were obtained using the method of Riethman et al. (1997) and have been reported previously (Macina et al. 1994, 1995; Negorev et al. 1994; Reston et al. 1995; National Institute of Health et al. 1996). In brief, sequence information from half-YAC vector-insert junction clones was used to design oligonucleotides that spanned known restriction endonuclease sites present in the insert sequences. The oligonucleotides were then used in RARE analyses of genomic DNA. The cleaved DNA was subjected to pulsed field gel electrophoresis, probed with single-copy sequences distal to the restriction endonuclease site and the distance of the restriction site from the telomere thereby inferred from the size of the hybridizing fragment.

Table 1.

Second-Generation Telomere Clones and Their Location

| Telomere | Clone ID | CloneType | MaximumPhysicalDistancefromTelomere(kb) | Method | Fiber-FISH (kb)a | RHMapping(cR) b | Marker |

| 1p | GS-62-L8 | PAC | 200 | Interphase mapping from subtelomeric sequences | 7.69 tel | 1PTEL06 | |

| GS-232-B23 | BAC | 200 | Interphase mapping from subtelomeric sequences | CEB108/T7 | |||

| 1q | GS-160-H23 | PAC | 80 | Contig | <50 | 1QTEL19 | |

| GS-167-K11 | BAC | 270 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 1QTEL10, 1QTEL19, VIJ-YRM2123 | |||

| 2p | GS-892-G20 | PAC | 330 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 2PTEL27 | ||

| GS-8-L3 | BAC | 330 | RARE from YAC end sequence | VIJ-YRM2052 | |||

| 2q | GS-1011-O17 | PAC | 240 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 2QTEL47 | ||

| RG-172-I13 | BAC | 240 | RARE from YAC end sequence | VIJ-YRM2112 | |||

| 3p | GS-1186-B18 | PAC | 450 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 150–250 | 3PTEL25 | |

| RG-228-K22 | BAC | 450 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 3PTEL25 | |||

| 3q | 196-F4 | PAC | 450 | YAC clone size | 3QTEL06 | ||

| GS-56-H22 | BAC | 450 | YAC clone size | 3QTEL05 | |||

| 4p | GS-36-P21 | PAC | 73 | Sequence: Z95704 | 80–100 | 4PTEL04 | |

| GS-118-B13 | BAC | 101 | Sequence: Z95704; walk from 4PTEL01 | GS10K2/T7 | |||

| 4q | GS-963-K6 | PAC | 275–500 | Contig (vanGeel et al. 1999) | 2.9 tel | 4QTEL11 | |

| GS-31-J3 | BAC | 300–700 c | Interphase distance from 4QTEL11 | AFMA224XH1 | |||

| 5p | GS-189-N21 | PAC | Unknown | 16.2 cen | 5PTEL48 | ||

| GS-24-H17 | BAC | Unknown | Distal marker of 5p contig | C84C11/T3 | |||

| 5q | GS-240-G13 | PAC | 245 | YAC clone size | 5QTEL70 | ||

| 6p | GS-62-I11 | PAC | 300 | Fiber FISH | <300 | 19.3 cen | 6PTEL48 |

| GS-196-I5 | BAC | 300 | 6PTEL48 | ||||

| 6q | GS-57-H24 | PAC | 280 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 6QTEL54 | ||

| 7p | GS-164-D18 | PAC | 255 | YAC clone size | ∼130 | 5.76 cen | 7PTEL03, VIJ-YRM2185 |

| 7q | GS-3K-23 | PAC | 7 | Sequence: AF027390 | 7QTEL20, VIJ-YRM2000 | ||

| 8p | GS-580-L5d | PAC | 250 | YAC clone size | NP | 8PTEL91 | |

| GS-77-L23 | BAC | 250–450 c | Interphase distance from 8PTEL91 | AFM197XG5 | |||

| 8q | GS-489-D14 | PAC | 170 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 8QTEL11 | ||

| GS-261-I1 | BAC | 170 | RARE from YAC end sequence | VIJ-YRM2053 | |||

| 9p | GS-43-N6 | PAC | 600 | YAC clone size | <600 | 13.9 tel | 9PTEL30 |

| RG-41-L13 | BAC | 190 | YAC clone size | 305J7-T7 | |||

| 9q | GS-112-N13d | PAC | 65 | YAC clone size | NP | 9QTEL33 | |

| GS-135-I17 | BAC | 65 | YAC clone size | VIJ-YRM2241 | |||

| 10p | GS-306-F7 | PAC | 320 | YAC clone size | ∼100 | 10PTEL45 | |

| GS-23-B11 | BAC | 320 | YAC clone size | 10PTEL006 | |||

| 10q | GS-137-E24 | PAC | 270 | YAC clone size | ∼100 | 10QTEL24 | |

| GS-261-B16 | BAC | 270 | YAC clone size | 10QTEL24 | |||

| 11p | GS-908-H22d | PAC | 125 | YAC clone size | NP | 11PTEL03 | |

| GS-44-H16 | PAC | 125 | YAC clone size | VIJ-YRM2209 | |||

| 11q | GS-770-G7d | PAC | 65 | YAC clone size | NP | 11QTEL38 | |

| GS-26-N8 | PAC | 65 | YAC clone size | VIJ-YRM2072 | |||

| 12p | GS-496-A11d | PAC | Unknown | TTAGGG clone | NP | 27.8 cen | 12PTEL27 |

| GS-8-M16d | BAC | 100 | YAC clone size | TYAC-14 | |||

| GS-124-K20 | BAC | 100 | YAC clone size | 8M16/SP6 | |||

| 12q | GS-221-K18 | PAC | 190 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 100/600e | 12QTEL87, VIJ-YRM2196 | |

| 13q | GS-163-C9 | PAC | 170 | RARE from YAC end sequence | <20 | 13QTEL56 | |

| GS-1-L16 | PAC | 170 | RARE from YAC end sequence | VIJ-YRM2002 | |||

| 14q | GS-820-M16 | PAC | 200 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 14QTEL01 | ||

| GS-200-D12 | BAC | 200 | RARE from YAC end sequence | VIJ-YRM2006 | |||

| 15q | GS-124-05d | PAC | 300c | Interphase mapping from 15q YAC | NP | 24.46 tel | 15QTEL56 |

| GS-154-P1 | PAC | 300c | Interphase mapping from 15q YAC | WI-5214 | |||

| 16p | GS-121-I4 | PAC | 160 | Sequence: Z84721 | 16PTEL05 | ||

| RG-191-K2 | BAC | 160 | Sequence: Z84721 | 16PTEL05 | |||

| 16q | GS-240-G10 | PAC | 200 | YAC clone size | 17.91 tel | 16QTEL48 | |

| GS-191-P24 | PAC | 200 | YAC clone size | 16QTEL13 | |||

| 17p | GS-202-L17d | PAC | 60 | Contig (Xiang et al. 1999) | 30/100e | 17PTEL80 | |

| GS-68-F18 | BAC | 100–200 | Walk from 17PTEL80 | 282M15/SP6 | |||

| 17q | GS-362-K4d | PAC | 90 | YAC clone size | NP | 17QTEL13 | |

| GS-50-C4 | BAC | 100–300 | Interphase distance from 17QTEL13 | AFM217YD10 |

Table 1 (Continued).

Second-Generation Telomere Clones and Their Location

| Telomere | Clone ID | CloneType | MaximumPhysicalDistancefromTelomere(kb) | Method | Fiber-FISH (kb)a | RHMapping(cR) b | Marker |

| Telomere | GS-1011-O17 | Clone | 250–450 c | Interphase distance from 17QTEL13 | Fiber-FISH | Mapping | 1QTEL10, 1QTEL19, VIJ-YRM2123 |

| 18q | GS-964-M9 | PAC | 290 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 18QTEL11 | ||

| GS-75-F20 | BAC | 290 | RARE from YAC end sequence | VIJ-YRM2050 | |||

| 19p | GS-546-C11 | PAC | 250–500 | LLNL chromosome 19 contig | NP | 16.13 tel | 19PTEL29 |

| RG-129-F16 | BAC | 250–500 | LLNL chromosome 19 contig | 129F16/SP6 | |||

| 19q | GS-48-O23 | PAC | 250–500 | LLNL chromosome 19 contig | 11.65 tel | 19QTEL12 | |

| GS-325-I23 | BAC | 250–500 | LLNL chromosome 19 contig | D19S238E | |||

| 20p | GS-1061-L1 | PAC | 180 | YAC clone size | 20PTHY33 | ||

| GS-82-O2 | PAC | 180 | YAC clone size | 20PTEL18 | |||

| 20q | GS-81-F12d | PAC | 50 | Fiber FISH | <50 | 28.2 tel | 20QTEL14 |

| 21q | GS-63-H24 | PAC | 175 | RARE from YAC end sequence | 21QTEL07 | ||

| GS-2-H14d | P1 | 175 | RARE from YAC end sequence | VIJ-YRM2029 | |||

| 22q | GS-99-K24d | PAC | 120 | Sequence: (Dunham et al. 1999) | 150–200 | 12.6 tel | 22QTEL31 |

| GS-3018-K1 | BAC | 155 | Sequence: (Dunham et al. 1999) | 3018K1/T7 | |||

| XpYp | GS-98-C4 | PAC | 490 | STS map (Nagaraja et al. 1997) | DXYS28 | ||

| GS-839-D20 | BAC | 160 | STS map (Nagaraja et al. 1997) | DXYS129 | |||

| XqYq | GS-225-F6 | BAC | 100 | CDY16C07 | |||

| Xq | GS-202-M24 | PAC | 500 | STS map (Nagaraja et al. 1997) | DXS7059 |

NP = not possible, because of cross-hybridization.

cen = centromeric; tel = telomeric.

The distance given is the sum of the size of the relevant half-YAC and the estimated interphase FISH distance between the BAC clone and a subtelomeric clone known to be contained within the half-YAC.

Cross-hybridization visible by FISH; see table 3 for details.

Fiber-FISH indicates a size polymorphism.

Results

Large-Format Clone Conversion

The telomere clones identified in this study are shown in table 1table 1, along with the evidence for telomeric localization. The corresponding primer sets used for library screening and newly developed STSs are listed in table 2 table 2. The map positions of the clones in relation to the telomere are derived from a combination of sequenced contig results, physical mapping, half-YAC sizes (determined by pulsed field gel electrophoresis), RARE analysis, radiation hybrid mapping of STSs, interphase FISH, and fiberFISH. Where complete sequence is available, the distance between the associated STS and the telomere is given. Since the physical distance from the telomere is not yet known for all STSs derived from half-YACs, the maximum distance given is the size of the half-YAC. However, clones isolated with the half-YAC vector-insert junction are expected to be more centromeric than those isolated with telomeric STSs, since the latter are derived from sequences telomeric to the vector-insert junction.

Table 2.

STSs for Telomere Clones

|

Primer(5′→3′) |

||||||

| Chromosome | Marker | Reference | ProductSize(bp) | Forward | Reverse | Clones |

| 1p | 1PTEL06 | This article | 121 | AGTCTGAAGGTGACAGCGGT | AGTGCTCGGAGCCTGGA | GS-62-L8 |

| 1p | CEB108/T7 | This article | 104 | GCCTTTAACAGAGACTGCGG | GAGGAGGAGGAAGGTTGAGG | GS-232-B23 |

| 1q | 1QTEL19 | D1S3739 | 156–189 | GGAGTTAAGGTTGAAGAGCC | TTCACGTACAACAGTATCTC | GS-160-H23 |

| 1q | 1QTEL10 | D1S3738 | 120 | GATCCATTCCTGTATGATGG | ACTCATTCTACGAAGTCAGC | GS-167-K11 |

| 2p | 2PTEL27 | D2S2983 | 230–242 | TATATACATTAGGAATAATAGGAGT | GTCCTCTCCATGTATAGA | GS-892-G20 |

| 2p | VIJ-YRM2052 | GenBank U32389 | 120 | GATCTCACTGCAATTTCTACA | TCCATTTTCTCCAAGTTATCA | GS-8-L3 |

| 2q | 2QTEL47 | D2S2983 | 146–162 | GTGAGGTCAGGAACGCTAAG | CTGTCATCGCTATGAGCCAG | GS-1011-O17 |

| 2q | VIJ-YRM2112 | D2S447 | 227 | AATTTACAGTGGCATTTCAGGC | CACACACAGCAGGGACGAC | RG-172-I13 |

| 3p | 3PTEL25 | D3S4559 | 182–190 | GCTAGCATGAGAATGTATAG | TACGCCTAATGAGATAACAG | GS-1186-B18, RG-228-K22 |

| 3q | 3QTEL06 | D3S1272 | 262–276 | TCACAAGGGAAATAACTGTTTTAC | TTCCTGTAACCCTCCAAAAT | GS-196-F4 |

| 3q | 3QTEL05 | D3S4560 | 150–164 | TCACAGTGGCCAAGATATCA | TCCATGTTGCTGCAAATGAC | GS-56-H22 |

| 4p | 4PTEL04 | D4S3360 | 166–182 | CTAGCTTTGATTCTATTGACC | GGTCTAAATCAATGACCTAAGC | GS-36-P21 |

| 4p | GS10K2/T7 | This article | 273 | TCAGAAGGACTGGGAGATGG | TAGAGTCCAGCCAGAAACCC | GS-118-B13 |

| 4q | 4QTEL11 | This article | 239–243 | AGGCAGTGAGAAAGGAATGG | TGCGTGTAAGTGTGTGCAAG | GS-963-K6 |

| 4q | AFMA224XH1 | D4S2930 | 219 | CCTCATGGTAGGTTAATCCCACG | TATTGAATGCCCGCCATTTG | GS-31-J3 |

| 5p | 5PTEL48 | This article | 219–231 | TAATTACCCTTGGCTACAGG | AGGCCTTGGAGGGAAGATTC | GS-189-N21 |

| 5p | C84C11/T3 | This article | 136 | GTTCTCATGTGTGACTCCCG | GGGGAGACACAGCCCATAG | GS-24-H17 |

| 5q | 5QTEL70 | D5S2097 | 191 | CTATTTTTATTTCAGTTGGCTGTTT | AAGGAAACGTTCCTCTAAGTTATTA | GS-40-G13 |

| 5q | GS35O8/T7 | This article | 150 | CTGCCTTTTGGGGAAGACC | TATGGAATGGAAGTGGTGCC | GS-240-G13 |

| 6p | 6PTEL48 | This article | 268–296 | GATAGGCCTAGAACTGTGAG | GTTTGTCCCTTTACCTCCCC | GS-62-L11, GS-196-I5 |

| 6q | 6QTEL54 | D6S2522 | 206–210 | CAGAACAGATTAAGACTCAG | GCATTTATCAACTTGTGTCC | GS-57-H4 |

| 6q | VIJ-YRM2158 | GenBank U11835 | 95 | TTTTGCACCAACATTATCAAGG | GCTGTGCAGGTCCTTGTTG | GS-57-H24b |

| 7p | 7PTEL03 | This article | 132 | ACCACCAGGCCTAAAGTGTG | CCGAGCTTAGTGTCCCAGAG | GS-164-D18 |

| 7p | VIJ-YRM2185 | GenBank G31341 | 357 | CCTGGGTGTGCCGTAAAC | TCACTGAGCTTGCTGGCTTA | GS-164-D18 |

| 7q | 7QTEL20 | This article | 217–235 | GCCCAGCCTGTGTATGGTTA | CTAAAGGAAGTTCTACAGG | GS-3K-23 |

| 7q | VIJ-YRM2000 | GenBank G31340 | 204 | CTCAATATCACACAACAGTG | GCTGAAAGGAAAACTGATTG | GS-3K-23 |

| 8p | 8PTEL91 | D8S2333 | 144 | CCCAGCATCTGACATGAGAA | TTATCGCTCAAGAAGTAGAC | GS-580-L5 |

| 8p | AFM197XG5 | D8S504 | 200 | ACTGGGTCACGAGGGA | CATGCCCATTTTCCAG | GS-77-L23 |

| 8q | 8QTEL11 | D8S1925 | 94–112 | TGAGATCTGTCTCTATACAC | CTACAGGTGTGTGCTACCAT | GS-489-D14 |

| 8q | VIJ-YRM2053 | GenBank U11829 | 75 | ATTCTCCTATGTTTCCTGGTGC | GTTCACCACTTCCCACTCTTG | GS-261-I1 |

| 9p | 9PTEL30 | This article | 241–245 | TCTCCGTCACTGCACTCCAG | CTGGCAGTGAGCCGAGATCG | GS-43-N6 |

| 9p | 305J7-T7 | GenBank AF170276 | 128 | TTACATTCCCTTTCATCACC | CACTGCACTCCAGTTTGG | RG-41-L13 |

| 9q | 9QTEL33 | D9S2168 | 122–130 | ATCTGTGTTGGATTCTTGGC | ACTGAACACACCTGTACAGG | GS-112-N13 |

| 9q | VIJ-YRM2241 | D9S325 | 90 | GGGAGTCCTACATCTGGAAGC | TGTGAAACTCACTCTACCAGCG | GS-135-I17 |

| 10p | 10PTEL45 | D10S2488 | 186–198 | TGGGTAACAGAGTGAGACTGTCTC | AGTACACTGATGATTTCATTTCCT | GS_306-F7 |

| 10p | 10PTEL006 | GenBank Z96139 | 167 | CTTCTAGCAAAACAGGTTGC | ACTGTCTTTTCATCCTACGC | GS-23-B11 |

| 10q | 10QTEL24 | D10S2490 | 163 | CTCCAAGGGTAACATTGAAC | CGTAAACGTTGTGAGATGGT | GS-137-E24, GS-261-B16 |

| 11p | 11PTEL03 | D11S2071 | 168–202 | AGGGCAATGAGGACATGAAC | ATGTGGCTGGTCCACCTG | GS-908-H22, GS-44-H16 |

| 11q | 11QTEL38 | D11S4974 | 158 | AGGGTCTAAGCTACCCAAAG | TATGCAGGTTCACAGTCACG | GS-770-G7 |

| 11q | VIJ-YRM2072 | 83 | AGCTCACTCCCTGTTAAGGTAA | CCTGGGCCACCATTTACTAG | GS-26-N8 | |

| 12p | 12PTEL27 | This article | 209 | ATGCCTCAGTTTGTCTTGGC | TGCCCAGAAGGTTTAACTGG | GS-496-A11 |

| 12p | TYAC-14 | Vocero-Akbani et al. (1996) | 140 | CCTCGGTTTAGCAGAGCAGC | GGGAGAATGGGGTCTCTCC | GS-8-M16 |

| 12p | 8M16/SP6 | This article | 333 | GTATTGAAATCCAATCTATGCCACC | CTCTCAAGTAATTCATATTCTTTGGG | GS-124-K20 |

| 12q | 12QTEL87 | D12S2343 | 170–174 | TGAGACTGCAGTGAACCATG | TCTTTCTTGAAGAGGAAGCC | GS-221-K18 |

| 12q | VIJ-YRM2196 | GenBank U11838 | 116 | GATGAGGGAGTTTGGGGG | AAGCCATTT CCACTCCTCCT | GS-221-K18b |

| 13q | 13QTEL56 | D13S1825 | 162–166 | TTGCAGTGAGCTGATATCGC | TAACAGGATCTCTGTAAGCG | GS-163-C9 |

| 13q | VIJ-YRM2002 | D13S327 | 210 | CAGAGGTAGCTTCATAAAG | CTATCTGCAACTTATTTA CC | GS-1-L16 |

| 14q | 14QTEL01 | D14S1420 | 174–182 | GTGCCTGTAGGTATCTATGC | GCTCCCTATTTGCAAGATAC | GS-820-M16 |

| 14q | VIJ-YRM2006 | D14S308 | 321 | GGCGTTTCTGATGTTTTTAAGC | GAGACGATGGAGGAGTGAGC | GS-200-D12 |

| 15q | 15QTEL56 | This article | 145 | CCATCTAGCCCGTCATGTTTT | AACTGAAAGCCACCACTTGG | GS-124-05 |

| 15q | WI-5214 | D15S936 | 124 | GTGGAAAATGATTTCCCTACTG | CATAACACATAACAGGCCCC | GS-154-P1a |

| 16p | 16PTEL05 | D16S3400 | 170–182 | AGCTGAGATCACGCCATTGC | TGTGAGGAGACAGGAAAGAG | GS-121-I4, RG-191-K2 |

| 16q | 16QTEL48 | This article | 94 | GCAGAGTTACAGACGGAGGC | TCTGGCCAAAGGGAATAAAA | GS-240-G10 |

| 16q | 16QTEL013 | GenBank Z96319 | 221 | AAAGCTCTCAGAACCTCCCC | AGAGGTTCCCATGTAGTTCC | GS-191-P24 |

| 17p | 17PTEL80 | D17S2199 | 190 | ACGCACATGCTTTCACGAAC | CCTGCCTTAGTGTTCCTGAG | GS-202-L17 |

| 17p | 282M15/SP6 | This article | 225 | GTGATGACTGTGGAAGACAGAGGAAG | CACAGTCTCAGAAATATGTTCTCC | GS-68-F18 |

| 17q | 17QTEL13 | D17S2200 | 233–235 | CGTGCCACTCAAATATAAAC | CAAAATAAAAACTGCAAGCAATATA | GS-36-K4 |

| 17q | AFM217YD10 | D17S928 | 150 | TAAAACGGCTACAACACATACA | ATTTCCCCACTGGCTG | GS-50-C4 |

| 18p | 18PTEL02 | D18S1389 | 220 | TCATTTATATGAAATTTCAAGGGAT | AAAAATAAAGCAATTGCTCATAGAA | GS-52-M11 |

| 18p | VIJ-YRM2102 | D18S552 | 103 | GGTAGGAGAGGAGGAAAAAAGC | CTGTCTTTGAGCCAGAAAGTCC | GS-74-G18 |

| 18q | 18QTEL11 | D18S1390 | 155 | CCTATTTAAGTTTCTGTAAGG | ATGGTGTAGACCCTGTGGAA | GS-964-M9 |

| 18q | VIJ-YRM2050 | NIH (1996) | 151 | GTGCCACGAGAACGTGAAC | ATTCCATCACCTAAAACATGGC | GS-75F-20 |

| 19p | 19PTEL29 | This article | 202 | AACAGGAAGACGGGAGTCCT | TGCAGACAACAGCAGGTACC | GS-546-C11 |

| 19p | 129F16/SP6 | LLNL Chromosome 19 map | 254 | ACTCAGCACCTCCCTCACAG | GTGTTT CCT GCTTCTCTGCC | RG-129-F16 |

| 19q | 19QTEL12 | This article | 148 | CACTACAGCCTGGCAGATGA | AACAAGCAAAGTCCACCTGG | GS-48-O23 |

| 19q | D19S238E | Ashworth et al. (1995) | 107 | TGCTCCAGGAAATTGGAGTT | CGAAGCACCACGCTGGTGCA | GS-325-I23 |

| 20p | 20PTHY33 | D20S502 | 245–261 | GGTTCAATGCTACTCAATGGC | AACCACACTGACATCGTAGTGG | GS-1061-L1 |

| 20p | 20PTEL18 | D20S1157 | 139–141 | GATAGTCACTTCAACAGATGG | GTTTGCCAGGCTCACATTTA | GS-82-O2 |

| 20q | 20QTEL14 | This article | 161 | CCAGCCTAGGTGACAAGAGC | AATGTCAGTGCCTCAACCCT | GS-81-F12 |

| 21q | 21QTEL07 | D21S1575 | 311–343 | GAAACCCATCTCACATGCAG | GAAGTGCTCTAAGAACTTGC | GS-63-H24 |

| 21q | VIJ-YRM2029 | (Reston et al. 1995) | 116 | AGGATAATATGTGATGGGCAGG | AGTCTTCTGTGTCCCTCAGCA | GS-2-H14b |

| 22q | 22QTEL31 | D22S1726 | 183 | TGCATTAGGTAGATGCTGGG | TACACTAGACCCAGGTGAAG | GS-99-K24 |

| 22q | 3018K1/T7 | GenBank AQ093314 | GS-3018-K1 | |||

| XpYp | DXYS28 | 275 | GGAACTGGCTTTTCATTTCC | AGGTCACCTGGATGGTCAGT | GS-98-C4 | |

| XpYp | DXYS129 | 164 | ATACTATGCAGTTTAAAGCG | AAGCTGGTGTTCAGCTGAAA | GS-839-D20 | |

| XqYq | CDY16C07 | GenBank Z43206 | 122 | AATATGTAGTAGAGGGGGTGG | AAACACTTTTCCCACACTACC | GS-225-F6 |

| Xq | DXS7059 | 187 | TAAATGTCATAGGCCGAAAGAATG | GTACCTAATCGCAAGAAACACTGT | GS-202-M24 | |

Table 2.

STSs for Telomere Clones

|

Primer(5′→3′) |

||||||

| Chromosome | Marker | Reference | ProductSize (bp) | Forward | Reverse | Clones |

| Chromosome | AFMA224XH1 | Vocero-Akbani et al. | Product | GTGATGACTGTGGAAGACAGAGGAAG | CTCTCAAGTAATTCATATTCTTTGGG | GS-1186-B18, RG-228-K22 |

| 1p | 1PTEL06 | This article | 121 | AGTCTGAAGGTGACAGCGGT | AGTGCTCGGAGCCTGGA | GS-62-L8 |

| 1p | CEB108/T7 | This article | 104 | GCCTTTAACAGAGACTGCGG | GAGGAGGAGGAAGGTTGAGG | GS-232-B23 |

| 1q | 1QTEL19 | D1S3739 | 156–189 | GGAGTTAAGGTTGAAGAGCC | TTCACGTACAACAGTATCTC | GS-160-H23 |

| 1q | 1QTEL10 | D1S3738 | 120 | GATCCATTCCTGTATGATGG | ACTCATTCTACGAAGTCAGC | GS-167-K11 |

| 2p | 2PTEL27 | D2S2983 | 230–242 | TATATACATTAGGAATAATAGGAGT | GTCCTCTCCATGTATAGA | GS-892-G20 |

| 2p | VIJ-YRM2052 | GenBank U32389 | 120 | GATCTCACTGCAATTTCTACA | TCCATTTTCTCCAAGTTATCA | GS-8-L3 |

| 2q | 2QTEL47 | D2S2983 | 146–162 | GTGAGGTCAGGAACGCTAAG | CTGTCATCGCTATGAGCCAG | GS-1011-O17 |

| 2q | VIJ-YRM2112 | D2S447 | 227 | AATTTACAGTGGCATTTCAGGC | CACACACAGCAGGGACGAC | RG-172-I13 |

| 3p | 3PTEL25 | D3S4559 | 182–190 | GCTAGCATGAGAATGTATAG | TACGCCTAATGAGATAACAG | GS-1186-B18, RG-228-K22 |

| 3q | 3QTEL06 | D3S1272 | 262–276 | TCACAAGGGAAATAACTGTTTTAC | TTCCTGTAACCCTCCAAAAT | GS-196-F4 |

| 3q | 3QTEL05 | D3S4560 | 150–164 | TCACAGTGGCCAAGATATCA | TCCATGTTGCTGCAAATGAC | GS-56-H22 |

| 4p | 4PTEL04 | D4S3360 | 166–182 | CTAGCTTTGATTCTATTGACC | GGTCTAAATCAATGACCTAAGC | GS-36-P21 |

| 4p | GS10K2/T7 | This article | 273 | TCAGAAGGACTGGGAGATGG | TAGAGTCCAGCCAGAAACCC | GS-118-B13 |

| 4q | 4QTEL11 | This article | 239–243 | AGGCAGTGAGAAAGGAATGG | TGCGTGTAAGTGTGTGCAAG | GS-963-K6 |

| 4q | AFMA224XH1 | D4S2930 | 219 | CCTCATGGTAGGTTAATCCCACG | TATTGAATGCCCGCCATTTG | GS-31-J3 |

| 5p | 5PTEL48 | This article | 219–231 | TAATTACCCTTGGCTACAGG | AGGCCTTGGAGGGAAGATTC | GS-189-N21 |

| 5p | C84C11/T3 | This article | 136 | GTTCTCATGTGTGACTCCCG | GGGGAGACACAGCCCATAG | GS-24-H17 |

| 5q | 5QTEL70 | D5S2097 | 191 | CTATTTTTATTTCAGTTGGCTGTTT | AAGGAAACGTTCCTCTAAGTTATTA | GS-40-G13 |

| 5q | GS35O8/T7 | This article | 150 | CTGCCTTTTGGGGAAGACC | TATGGAATGGAAGTGGTGCC | GS-240-G13 |

| 6p | 6PTEL48 | This article | 268–296 | GATAGGCCTAGAACTGTGAG | GTTTGTCCCTTTACCTCCCC | GS-62-L11, GS-196-I5 |

| 6q | 6QTEL54 | D6S2522 | 206–210 | CAGAACAGATTAAGACTCAG | GCATTTATCAACTTGTGTCC | GS-57-H4 |

| 6q | VIJ-YRM2158 | GenBank U11835 | 95 | TTTTGCACCAACATTATCAAGG | GCTGTGCAGGTCCTTGTTG | GS-57-H24b |

| 7p | 7PTEL03 | This article | 132 | ACCACCAGGCCTAAAGTGTG | CCGAGCTTAGTGTCCCAGAG | GS-164-D18 |

| 7p | VIJ-YRM2185 | GenBank G31341 | 357 | CCTGGGTGTGCCGTAAAC | TCACTGAGCTTGCTGGCTTA | GS-164-D18 |

| 7q | 7QTEL20 | This article | 217–235 | GCCCAGCCTGTGTATGGTTA | CTAAAGGAAGTTCTACAGG | GS-3K-23 |

| 7q | VIJ-YRM2000 | GenBank G31340 | 204 | CTCAATATCACACAACAGTG | GCTGAAAGGAAAACTGATTG | GS-3K-23 |

| 8p | 8PTEL91 | D8S2333 | 144 | CCCAGCATCTGACATGAGAA | TTATCGCTCAAGAAGTAGAC | GS-580-L5 |

| 8p | AFM197XG5 | D8S504 | 200 | ACTGGGTCACGAGGGA | CATGCCCATTTTCCAG | GS-77-L23 |

| 8q | 8QTEL11 | D8S1925 | 94–112 | TGAGATCTGTCTCTATACAC | CTACAGGTGTGTGCTACCAT | GS-489-D14 |

| 8q | VIJ-YRM2053 | GenBank U11829 | 75 | ATTCTCCTATGTTTCCTGGTGC | GTTCACCACTTCCCACTCTTG | GS-261-I1 |

| 9p | 9PTEL30 | This article | 241–245 | TCTCCGTCACTGCACTCCAG | CTGGCAGTGAGCCGAGATCG | GS-43-N6 |

| 9p | 305J7-T7 | GenBank AF170276 | 128 | TTACATTCCCTTTCATCACC | CACTGCACTCCAGTTTGG | RG-41-L13 |

| 9q | 9QTEL33 | D9S2168 | 122–130 | ATCTGTGTTGGATTCTTGGC | ACTGAACACACCTGTACAGG | GS-112-N13 |

| 9q | VIJ-YRM2241 | D9S325 | 90 | GGGAGTCCTACATCTGGAAGC | TGTGAAACTCACTCTACCAGCG | GS-135-I17 |

| 10p | 10PTEL45 | D10S2488 | 186–198 | TGGGTAACAGAGTGAGACTGTCTC | AGTACACTGATGATTTCATTTCCT | GS_306-F7 |

| 10p | 10PTEL006 | GenBank Z96139 | 167 | CTTCTAGCAAAACAGGTTGC | ACTGTCTTTTCATCCTACGC | GS-23-B11 |

| 10q | 10QTEL24 | D10S2490 | 163 | CTCCAAGGGTAACATTGAAC | CGTAAACGTTGTGAGATGGT | GS-137-E24, GS-261-B16 |

| 11p | 11PTEL03 | D11S2071 | 168–202 | AGGGCAATGAGGACATGAAC | ATGTGGCTGGTCCACCTG | GS-908-H22, GS-44-H16 |

| 11q | 11QTEL38 | D11S4974 | 158 | AGGGTCTAAGCTACCCAAAG | TATGCAGGTTCACAGTCACG | GS-770-G7 |

| 11q | VIJ-YRM2072 | 83 | AGCTCACTCCCTGTTAAGGTAA | CCTGGGCCACCATTTACTAG | GS-26-N8 | |

| Chromosome | AFMA224XH1 | Vocero-Akbani et al. | Product | GTGATGACTGTGGAAGACAGAGGAAG | CTCTCAAGTAATTCATATTCTTTGGG | GS-1186-B18, RG-228-K22 |

| 12p | 12PTEL27 | This article | 209 | ATGCCTCAGTTTGTCTTGGC | TGCCCAGAAGGTTTAACTGG | GS-496-A11 |

| 12p | TYAC-14 | Vocero-Akbani et al. (1996 ) | 140 | CCTCGGTTTAGCAGAGCAGC | GGGAGAATGGGGTCTCTCC | GS-8-M16 |

| 12p | 8M16/SP6 | This article | 333 | GTATTGAAATCCAATCTATGCCACC | CTCTCAAGTAATTCATATTCTTTGGG | GS-124-K20 |

| 12q | 12QTEL87 | D12S2343 | 170–174 | TGAGACTGCAGTGAACCATG | TCTTTCTTGAAGAGGAAGCC | GS-221-K18 |

| 12q | VIJ-YRM2196 | GenBank U11838 | 116 | GATGAGGGAGTTTGGGGG | AAGCCATTT CCACTCCTCCT | GS-221-K18b |

| 13q | 13QTEL56 | D13S1825 | 162–166 | TTGCAGTGAGCTGATATCGC | TAACAGGATCTCTGTAAGCG | GS-163-C9 |

| 13q | VIJ-YRM2002 | D13S327 | 210 | CAGAGGTAGCTTCATAAAG | CTATCTGCAACTTATTTA CC | GS-1-L16 |

| 14q | 14QTEL01 | D14S1420 | 174–182 | GTGCCTGTAGGTATCTATGC | GCTCCCTATTTGCAAGATAC | GS-820-M16 |

| 14q | VIJ-YRM2006 | D14S308 | 321 | GGCGTTTCTGATGTTTTTAAGC | GAGACGATGGAGGAGTGAGC | GS-200-D12 |

| 15q | 15QTEL56 | This article | 145 | CCATCTAGCCCGTCATGTTTT | AACTGAAAGCCACCACTTGG | GS-124-05 |

| 15q | WI-5214 | D15S936 | 124 | GTGGAAAATGATTTCCCTACTG | CATAACACATAACAGGCCCC | GS-154-P1a |

| 16p | 16PTEL05 | D16S3400 | 170–182 | AGCTGAGATCACGCCATTGC | TGTGAGGAGACAGGAAAGAG | GS-121-I4, RG-191-K2 |

| 16q | 16QTEL48 | This article | 94 | GCAGAGTTACAGACGGAGGC | TCTGGCCAAAGGGAATAAAA | GS-240-G10 |

| 16q | 16QTEL013 | GenBank Z96319 | 221 | AAAGCTCTCAGAACCTCCCC | AGAGGTTCCCATGTAGTTCC | GS-191-P24 |

| 17p | 17PTEL80 | D17S2199 | 190 | ACGCACATGCTTTCACGAAC | CCTGCCTTAGTGTTCCTGAG | GS-202-L17 |

| 17p | 282M15/SP6 | This article | 225 | GTGATGACTGTGGAAGACAGAGGAAG | CACAGTCTCAGAAATATGTTCTCC | GS-68-F18 |

| 17q | 17QTEL13 | D17S2200 | 233–235 | CGTGCCACTCAAATATAAAC | CAAAATAAAAACTGCAAGCAATATA | GS-36-K4 |

| 17q | AFM217YD10 | D17S928 | 150 | TAAAACGGCTACAACACATACA | ATTTCCCCACTGGCTG | GS-50-C4 |

| 18p | 18PTEL02 | D18S1389 | 220 | TCATTTATATGAAATTTCAAGGGAT | AAAAATAAAGCAATTGCTCATAGAA | GS-52-M11 |

| 18p | VIJ-YRM2102 | D18S552 | 103 | GGTAGGAGAGGAGGAAAAAAGC | CTGTCTTTGAGCCAGAAAGTCC | GS-74-G18 |

| 18q | 18QTEL11 | D18S1390 | 155 | CCTATTTAAGTTTCTGTAAGG | ATGGTGTAGACCCTGTGGAA | GS-964-M9 |

| 18q | VIJ-YRM2050 | NIH (1996) | 151 | GTGCCACGAGAACGTGAAC | ATTCCATCACCTAAAACATGGC | GS-75F-20 |

| 19p | 19PTEL29 | This article | 202 | AACAGGAAGACGGGAGTCCT | TGCAGACAACAGCAGGTACC | GS-546-C11 |

| 19p | 129F16/SP6 | LLNL Chromosome 19 map | 254 | ACTCAGCACCTCCCTCACAG | GTGTTT CCT GCTTCTCTGCC | RG-129-F16 |

| 19q | 19QTEL12 | This article | 148 | CACTACAGCCTGGCAGATGA | AACAAGCAAAGTCCACCTGG | GS-48-O23 |

| 19q | D19S238E | Ashworth et al. (1995) | 107 | TGCTCCAGGAAATTGGAGTT | CGAAGCACCACGCTGGTGCA | GS-325-I23 |

| 20p | 20PTHY33 | D20S502 | 245–261 | GGTTCAATGCTACTCAATGGC | AACCACACTGACATCGTAGTGG | GS-1061-L1 |

| 20p | 20PTEL18 | D20S1157 | 139–141 | GATAGTCACTTCAACAGATGG | GTTTGCCAGGCTCACATTTA | GS-82-O2 |

| 20q | 20QTEL14 | This article | 161 | CCAGCCTAGGTGACAAGAGC | AATGTCAGTGCCTCAACCCT | GS-81-F12 |

| 21q | 21QTEL07 | D21S1575 | 311–343 | GAAACCCATCTCACATGCAG | GAAGTGCTCTAAGAACTTGC | GS-63-H24 |

| 21q | VIJ-YRM2029 | (Reston et al. 1995) | 116 | AGGATAATATGTGATGGGCAGG | AGTCTTCTGTGTCCCTCAGCA | GS-2-H14b |

| 22q | 22QTEL31 | D22S1726 | 183 | TGCATTAGGTAGATGCTGGG | TACACTAGACCCAGGTGAAG | GS-99-K24 |

| 22q | 3018K1/T7 | GenBank AQ093314 | GS-3018-K1 | |||

| XpYp | DXYS28 | 275 | GGAACTGGCTTTTCATTTCC | AGGTCACCTGGATGGTCAGT | GS-98-C4 | |

| XpYp | DXYS129 | 164 | ATACTATGCAGTTTAAAGCG | AAGCTGGTGTTCAGCTGAAA | GS-839-D20 | |

| XqYq | CDY16C07 | GenBank Z43206 | 122 | AATATGTAGTAGAGGGGGTGG | AAACACTTTTCCCACACTACC | GS-225-F6 |

| Xq | DXS7059 | 187 | TAAATGTCATAGGCCGAAAGAATG | GTACCTAATCGCAAGAAACACTGT | GS-202-M24 |

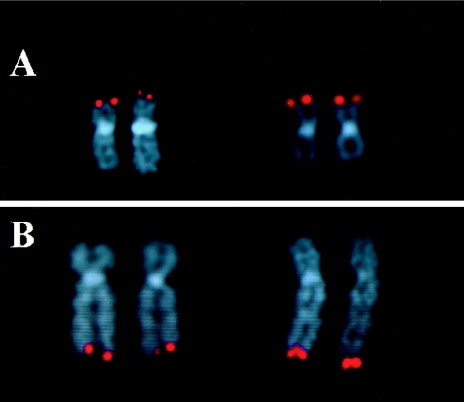

Figure 1 shows a comparison of metaphase FISH results obtained with a cosmid clone compared to those obtained with a BAC clone. As is evident, the BAC clone produces a larger hybridization signal that is more easily visualized than the cosmid clone. Images for other telomere BAC, PAC, and P1 clones can be viewed at the University of Chicago Department of Human Genetics Web page. The PAC polymorphism and cross-hybridization profiles are provided in table 3. The 2q PAC (1011-O17) still detects the common polymorphism encountered previously, but the stronger hybridization signal reduces the likelihood of misinterpretation compared to the original 2112b2 cosmid. The XpYp PAC (98-C4) does not contain the polymorphism previously encountered with the first-generation cosmid. Overall, the larger clones are more robust for multiplex FISH assays where more than one telomere clone is used per hybridization area. Larger–format clones are also better suited for other genomewide scanning methods, such as comparative genome hybridization (CGH) to microarrays, where larger insert sizes are expected to give improved signals because there are more sequences to which the labeled target DNA can hybridize.

Figure 1.

Comparison of FISH results obtained with a cosmid clone compared to a BAC clone for the 19p and 10q telomeres. All probes are labeled with digoxigenin and detected with antidigoxigenin rhodamine (red). A, Hybridization of cosmid clone, cF20643 (left), and BAC clone, RG129F16 (right), corresponding to the 19p telomere. B, Hybridization of cosmid clone, c2136c3 (left), and BAC clone, GS261B16 (right), corresponding to the 10q telomere. In both A and B, notice the difference in signal intensity between the two telomere clones; the BAC clone shows a larger signal compared to that of the cosmid clone.

Table 3.

Cross-hybridization and Polymorphisms of Second-Generation PACs

| Telomere | Probe |

| Polymorphisms: | |

| 2q | GS-1011-O17 |

| Cross-hybridizations: | |

| 8p with 1p and 3q (both faint) | GS-580-L5 |

| 9q with 10p and 16p, 18p, XqYq (faint) | GS-112-N13 |

| 11p with 17p | GS-908-H22 |

| 11q with 12q (interstitial) | GS-770-G7 |

| 12p with 6p and 20q (both faint) | GS-496-A11 |

| 12p with 6p and 20q (both faint) | GS-8-M16 |

| 15q with 1q (interstitial) and 15q (interstitial) | GS-124-O5 |

| 17p with 17q (two interstitial sites) | GS-202-L17 |

| 17q with 1p and 6q (both faint) | GS-362-K4 |

| 20q with 6p (faint) | GS-81-F12 |

| 22q with 2q (interstitial) | GS-99-K24 |

New Telomere Clones

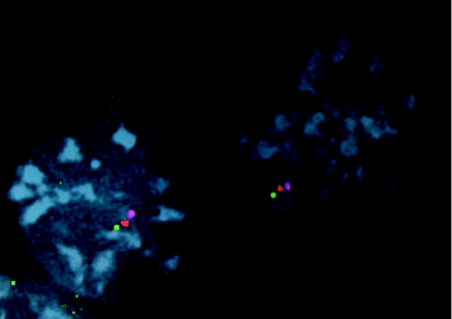

New telomere clones for 1p, 5p, 6p, 9p, 12p, 15q, and 20q were isolated using multiple strategies. To identify a telomeric clone for 1p, we first generated an STS from the cosmid clone CEB108 (National Institutes of Health et al. 1996) and identified large insert clones, including the BAC clone GS-232-B23. We then used three-color interphase FISH to determine the relationship of this BAC clone with respect to the telomere. This was achieved by use of two other clones, PAC GS-63-M14 and BAC GS-145-I23. GS-63-M14 is derived from the 8p telomere but contains subtelomeric sequences with homology to 1p (observed as cross-hybridization by metaphase FISH) and GS-145-I23 is derived from the 17q telomere but shows cross-hybridization to multiple telomeres, including 1p. The cross-hybridization of GS-145-I23 to multiple telomeres indicates that it is more telomeric than GS-63-M14, which only cross-hybridizes to 1p (Flint et al. 1997b). Hence, for the three-color interphase FISH, GS-145-I23 served as the telomeric anchor to determine the order and distance of GS-232-B23 with respect to GS-63-M14. By using a monochromosomal hybrid cell line containing only human chromosome 1, the cross-hybridization signals from the other subtelomeric repeat sequences were eliminated, thus allowing a more clear interpretation. As shown in figure 2, interphase ordering showed tel-GS-145-I23-GS63M14-GS232B23-cen. The genomic distance between GS-63-M14 and GS-232-B23 was estimated to be <200 kb using interphase FISH measurements on G0 fibroblasts.

Figure 2.

Three-color interphase FISH ordering at the human 1p telomere. Interphase cells from a chromosome 1 monochromosomal hybrid cell line were hybridized with three probes from the telomeric region of chromosome 1p. GS-232-B23 is labeled with biotin and detected with avidin-Cy5 (purple), PAC GS-63-M14 is labeled with Spectrum Orange (red) and BAC GS-145-I23 is labeled with digoxigenin and detected with anti-digoxigenin FITC (green). The order of these clones was determined to be tel-GS145I23-GS63M14-GS232B23-cen.

In our first-generation set of telomere clones, the telomeric region of chromosome 5p was represented by cosmid 84C11 (National Institutes of Health et al. 1996). At that time, no link (such as a half-YAC clone) to the telomere of 5p was available, and, therefore, cosmid 84C11 was utilized, because it was the most distal clone yet identified. Since that report, despite many efforts, we have been unable to find unequivocal evidence of telomeric localization for the chromosome 5p clones; a 5p half-YAC clone has not been identified, and no subtelomeric clones have shown cross-hybridization to the 5p region, which could anchor the telomeric end of the chromosome. Peterson et al. (1999) recently published an integrated physical map for chromosome 5p. They used a somatic cell hybrid panel of 5p, created from patients with 5p deletions, to approximate the location of the 5p telomere. The most distal STS on their map of 5p is derived from the end sequence from cosmid 84C11. Therefore, end-sequence from cosmid 84C11 was used to identify PAC GS24H17; both ends of the cosmid are contained within the PAC clone.

The identification of telomere clones for 9p, 12p, and 15q was previously reported (Lese et al. 1999) and thus are briefly summarized here. STSs designed from half-YAC vector-insert junction sequences were used to isolate clones for the 9p and 12p telomeres. For the 15q telomere, PAC GS-154-P1 (isolated with distal marker, WI-5214) was shown to be <100 kb from a chromosome 19–derived subtelomeric clone, GS-196-D24. GS-196-D24 was isolated using the vector-insert junction sequence from half-YAC yRM2001, and it contains 15q and other telomeric sequences, observed as cross-hybridization in a FISH assay.

To identify the remaining telomere clones (6p and 20q), a total genomic PAC library was screened by hybridization using an oligonucleotide for the telomeric repeat sequence (TTAGGG)n, thereby identifying 75 clones. FISH showed that seven of these were telomere-specific, hybridizing to 5p, 6p, 8p, 10p, 12p, 20q, and 22q. Of the remaining (TTAGGG)n positive PACs, 39 hybridized to multiple telomeres, whereas 7 mapped to multiple centromeres and 19 were located in interstitial regions.

Using interphase FISH, the distance of the 6p PAC clone, 62I11, from the most distal marker utilized previously (PAC GS-36-I2, AFMA339YD9) was estimated to be >1.5 Mb. This result demonstrates a substantial gap in the integrated physical and genetic maps for the telomeric region of chromosome 6p. At low-stringency washes, PAC GS-62I-11 showed faint cross-hybridization to the 20q telomere, and, therefore, sequence information from this clone was used for further library screening. This resulted in the isolation of clone GS-196-I5 which hybridized only to the 6p telomere. The distance of four of the new clones from their cognate telomeres (1p, 5p, 6p, and 20q) was unknown and was estimated by RH mapping and fiberFISH.

RH Mapping

RH mapping was used to localize STSs generated from (1) the TTAGGG positive clones (5p, 6p, 12p, and 20q), (2) unmapped first-generation clones, and (3) from unmapped half-YAC derived clones (1p, 4q, 7p, 9p, 15q, 16q, 19p, 19q, and 22q). The results of the radiation-hybrid mapping studies are shown intable 1table 1. All STSs mapped telomeric to the most distal framework markers currently on the RH map with LOD scores >13, with the exception of those from the 5p, 6p, 7p, and 12p PACs.

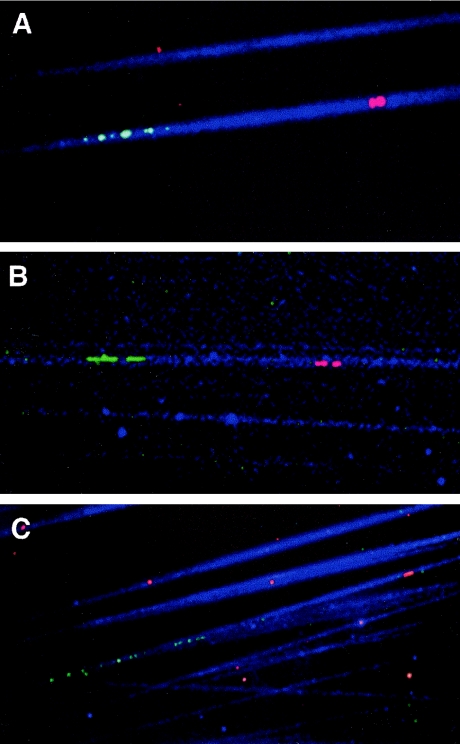

FiberFISH

FiberFISH confirmed the telomeric localization of 13 PAC clones and enabled the distance between each of these and the canonical (TTAGGG)n repeat to be estimated (table 1table 1). An explanation of the derivation of fiberFISH distances is given in figure 3. An example of the fiberFISH images obtained for the control probes for 4p (cosmid B31) and 16p (cosmid GG4), and an image for the second generation 7p PAC clone is given in figure 4. The control probe for 4p is known to lie ∼70 kb from the telomere, and the fiberFISH distance shown in figure 4 was calculated to be ∼80 kb. For 16p, the control probe lies 81 kb from the telomere, and the fiberFISH distance shown was calculated to be ∼100 kb. These results confirmed the validity of the fiberFISH approach for estimation of the distances between the new telomere clones and their respective telomeres.

Figure 4.

FiberFISH results showing telomere-specific probe signals in green and (TTAGGG)n probe signals in red. A, Control hybridization showing 4p cosmid (B31: ∼33 kb insert) ∼80 kb from the (TTAGGG)n repeat sequence. B, control hybridization showing 16p cosmid (cGG4: ∼36 kb insert) ∼100 kb from the (TTAGGG)n repeat. C, test hybridization showing 7p PAC (164-D18) ∼130 kb from the (TTAGGG)n repeat.

At the 12q and 17p telomeres, two different fiberFISH size estimates were obtained on the same DNA sample. The DNA strands of different lengths occurred at equal frequency on the slide, indicating the presence of an allelic difference. We interpret this as evidence for large-scale size polymorphisms on 12q and 17p, as has already been documented for 16p (Wilkie et al. 1991).

Discussion

We have developed a second-generation set of telomere-specific BAC, PAC, and P1 clones that have been characterized using a combination of FISH (metaphase, interphase, and fiber), sequence analysis, and RH mapping. A combined approach was taken because no single method of characterization was informative in all situations. With the exception of 5p, telomeric evidence has been provided for each clone. The updated set of human telomere clones provides a resource for investigating the frequency and mechanism of telomeric rearrangements, as well as more detailed biological studies of the architecture and evolution of human telomeres. Telomeric clones are available to the research community via the Bacpac Web site or from Genome Systems or Research Genetics. We have provided a PCR assay for each clone, making it simple to check that the correct clone has been obtained. The FISH probes are also available commercially through Vysis or Cytocell.

In the absence of accurate physical maps of each telomere, our estimates of the distance from the telomere to each clone are still approximate, but the data indicate that the clones are within 500 kb of each telomere. Where possible, we have mapped clones by fiberFISH. However, in many cases, the clones showed weak cross-hybridization to other chromosomes, making it difficult to discriminate between the cognate signals and those of homologous chromosomes in a fiberFISH assay. In other cases, results were not obtained, either because the (TTAGGG)n target sequence was too short to give a clear, interpretable signal (telomere sizes range from 2–20 kb) or because the resolution of the fibers was not sufficiently high. For the majority of cases, the former of these is considered the most likely, since characterization of the same clones (e.g., the 8p and 8q PACs) by alternative methods indicated distances <300 kb from the telomere, a resolution within the means of fiberFISH (table 1table 1). We observed fibers extending beyond the telomere-specific hybridization signals (fig. 4), which we interpret as being caused by fibers from different chromosomal regions remaining together and overlapping as they were pulled across the microscope slide.

We previously reported the characterization of physical gap sizes for 9 human telomeres by measuring the distance between each telomere clone and the corresponding most distal marker (Lese et al. 1999). Gaps in the physical/genetic maps, ranging from <100 kb to >1 Mb, were identified. For clinical testing purposes, these data demonstrate that clones corresponding to distal markers would miss smaller telomeric rearrangements. Thus, clones that are a known distance from the end of the chromosome are the optimal reagents for identifying subtle telomeric rearrangements. Furthermore, the fact that some gaps are ⩾1 Mb underscores the importance of more-targeted mapping efforts in these regions to facilitate gene identification and obtain telomeric closure.

As with the first-generation probes, in developing the second-generation set of telomere-specific clones, the need for the clones to be close enough to the telomere to detect rearrangements was balanced with the need for chromosome specificity. Hence, a number of the clones show cross-hybridization with other chromosomes (table 3). With the exception of the cross-hybridization of 9q with 16q, the signals from the homologous chromosomal regions were much weaker than the cognate telomeric signal. The 2q PAC still detects a polymorphism, but the stronger hybridization signal, resulting from the large insert size, reduces the likelihood of misinterpretation in comparison to the original 2112b2 cosmid. For the XpYp clone, the problem of polymorphism was overcome.

The size of the clones (on average 100–200 kb) means that, in general, they provide a stronger FISH signal than does the first-generation set of cosmids. Moreover, they are still small enough to detect rearrangements involving the terminal 200 kb of a chromosome (Wong et al. 1997). The identification of this updated set of human telomere clones provides a valuable new set of tools for clinical diagnosis and for studies of telomere structure and function. Already some of the PACs have been used in conjunction with the first-generation set of clones to confirm that submicroscopic, subtelomeric rearrangements are found in 7.4% of individuals with previously undiagnosed, moderate-to-severe mental retardation (Knight et al. 1999). The clones represent a major step in the generation of molecular tools, which will expedite telomeric gap closure and will help us to elucidate telomere structure and function, ultimately leading to the identification of dosage-sensitive genes involved in human genetic disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a National Research Service Award (1 F32 HG00174-01 to C.M.L.), through the National Human Genome Research Institute, and by grants from the March of Dimes (6-FY99-641 to D.H.L.), the National Institutes of Health (1-R01-HD36715-01 to D.H.L.), the Wellcome Trust (to J.F. and S.J.L.K.), Cytocell Ltd. (to J.F.), and Vysis, Inc. (to D.H.L.). The authors would like to thank Dr. Nicola Royle for the (TTAGGG)n plasmid and primers and Dr. Gilles Vergnaud for providing cosmids from 1p. The authors would also like to acknowledge Judith Fantes, Ph.D., for critical scientific discussions and Jessica Roseberry and Alyssa Gross for excellent technical assistance. D.H.L. serves as a consultant and member of the scientific advisory board for Vysis, Inc.

Electronic-Database Information

Accession numbers and URLs for data in this article are as follows:

- Bacpac Web site, http://www.chori.org/bacpac/home.htm

- Comprehensive genetic map, http://www.marshmed.org/genetics/ (for distal marker identification)

- GenBank, http://www.ncbi.nlm.gov/Genbank/GenbankSearch.html (for primers and sequence information)

- Généthon map, http://www.genethon.fr/genethon_en.html (for distal marker identification)

- Genome Database, http://gdbwww.gdb.org/ (for primer information)

- Integrated physical map, http://carbon.wi.mit.edu:8000/cgi-bin/contig/phys_map (for distal marker identification)

- Lawrence Livermore chromosome 19 map, http://www.bio.llnl.gov/genome/html/chrom_map.html (for chromosome 19p and 19q markers)

- Primer 3, http://www.genome.wi.mit.edu/genome_software/other/primer3.html (for primer development)

- TIGR end-sequence database, http://www.tigr.org/tdb/humgen/bac_end_search/bac_end_search.html (used to identify 22q telomere BAC clone)

- University of Chicago, Department of Human Genetics, http://www.genes.uchicago.edu (for additional pictures of human telomere clones)

References

- Ashworth LK, Batzer MA, Brandriff B, Branscomb E, de Jong P, Garcia E, Garnes JA, et al (1995) An integrated metric physical map of human chromosome 19. Nat Genet 11:422–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates GP, MacDonald ME, Baxendale S, Sedlacek Z, Youngman S, Romano D, Whaley WL, et al (1990) A yeast artificial chromosome telomere clone spanning a possible location of the Huntington's disease gene. Am J Hum Genet 46:762–775 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WRA (1989) Molecular cloning of human telomeres in yeast. Nature 338:774–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WRA, MacKinnon PJ, Villasanté A, Spurr N, Buckle VJ, Dodson MJ (1990) Structure and polymorphism of human telomere-associated DNA. Cell 63:119–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckle VJ, Rack K (1993) Fluorescent in situ hybridization. In: Davies KE (ed) Human genetic diseases: a practical approach. IRL Press, Oxford, pp 59–80 [Google Scholar]

- Chong SS, Pack SD, Roschke AV, Tanigami A, Carrozzo R, Smith AC, Dobyns WB, et al (1997) A revision of the lissencephaly and Miller-Dieker syndrome critical regions in chromosome 17p13.3. Hum Mol Genet 6:147–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross SH, Allshire RC, McKay SJ, McGill NI, Cooke HJ (1989) Cloning of human telomeres by complementation in yeast. Nature 338:771–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham I, Shimizu N, Roe BA, Chissoe S, Dunham I, Hunt AR, Collins JE, et al (1999) The DNA sequence of human chromosome 22. Nature 402:489–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrin LJ, Camerini-Otero RD (1991) Selective cleavage of human DNA: RecA-assisted restriction endonuclease (RARE) cleavage. Science 254:1494–1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ——— (1994) Long-range mapping of gaps and telomeres with RecA-assisted restriction endonuclease (RARE) cleavage. Nat Genet 6:379–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint J, Bates GP, Clark K, Dorman A, Willingham D, Roe BA, Micklem G, et al (1997b) Sequence comparison of human and yeast telomeres identifies structurally distinct subtelomeric domains. Hum Mol Genet 6:1305–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint J, Sims M, Clark K, Staden R, Thomas K (1998) An oligo-screening strategy to fill gaps found during shotgun sequencing projects. DNA Seq 8:241–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint J, Thomas K, Micklem G, Raynham H, Clark K, Doggett NA, King A, et al (1997a) The relationship between chromosome structure and function at a human telomeric region. Nat Genet 15:252–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiskanen M, Kallioniemi O, Palotie A (1996) Fiber-FISH: experiences and a refined protocol. Genet Anal 12:179-184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holinski-Feder E, Reyniers E, Uhrig S, Golla A, Wauters J, Kroisel P, Bossuyt P, et al (2000) Familial mental retardation syndrome ATR-16 due to an inherited cryptic subtelomeric translocation, t(3;16)(q29;p13.3). Am J Hum Genet 66:16–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsley SW, Knight SJL, Nixon J, Huson S, Fitchett M, Boone RA, Hilton Jones D, et al (1998) Del(18p) shown to be a cryptic translocation using a multiprobe FISH assay for subtelomeric chromosome rearrangements. J Med Genet 35:722–726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight SJL, Horsley SW, Regan R, Lawrie NM, Maher EJ, Cardy DLN, Flint J, et al (1997) Development and clinical application of an innovative fluorescence in situ hybridization technique which detects submicroscopic rearrangements involving telomeres. Eur J Hum Genet 5:1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight SJL, Regan R, Nicod A, Horsley SW, Kearney L, Homfray T, Winter RM, et al (1999) Subtle chromosomal rearrangements in children with unexplained mental retardation. Lancet 354:1676–1681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lese CM, Fantes JA, Riethman HC, Ledbetter DH (1999) Characterization of physical gap sizes at human telomeres. Genome Res 9:888–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macina RA, Morii K, Hu XL, Negorev DG, Spais C, Ruthig LA, Riethman HC (1995) Molecular cloning and RARE cleavage mapping of human 2p, 6q, 8q, 12q, and 18q telomeres. Genome Res 5:225–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macina RA, Negorev DG, Spais C, Ruthig LA, Hu XL, Riethman HC (1994) Sequence organization of the human chromosome 2q telomere. Hum Mol Genet 3:1847–1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto N, Soeda E, Ohashi H, Fujimoto M, Kato R, Tsujita T, Tomita H, et al (1997) A 1.2-megabase BAC/PAC contig spanning the 14q13 breakpoint of t(2; 14) in a mirror-image polydactyly patient. Genomics 45:11–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monfouilloux S, Avet Loiseau H, Amarger V, Balazs I, Pourcel C, Vergnaud G (1998) Recent human-specific spreading of a subtelomeric domain. Genomics 51:165–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraja R, MacMillan S, Kere J, Jones C, Griffin S, Schmatz M, Terrell J, et al (1997) X chromosome map at 75-kb STS resolution, revealing extremes of recombination and GC content. Genome Res 7:210–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health, Institute of Molecular Medicine Collaboration, Ning Y, Roschke A, Smith AC, Macha M, Precht K, et al (1996) A complete set of human telomeric probes and their clinical application. Nat Genet 14:86–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negorev DG, Macina RA, Spais C, Ruthig LA, Hu X-L, Riethman HC (1994) Physical analysis of the terminal 270 kb of DNA from human chromosome 1q. Genomics 22:569–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Y, Rosenberg M, Biesecker LG, Ledbetter DH (1996) Isolation of the human chromosome 22q telomere and its application to detection of cryptic chromosomal abnormalities. Hum Genet 97:765–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson ET, Sutherland R, Robinson DL, Chasteen L, Gersh M, Overhauser J, Deaven LL, et al (1999) An integrated physical map for the short arm of human chromosome 5. Genome Res 9:1250–1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reston JT, Hu XL, Macina RA, Spais C, Riethman HC (1995) Structure of the terminal 300 kb of DNA from human chromosome 21q. Genomics 26:31–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riethman H, Birren B, Gnirke A (1997) Preparation, manipulation and mapping of high molecular weight DNA. In: Birren B, Green E, Klapholz S, Meyers R, Roskams J (eds) Genome analysis: a laboratory manual. Vol. 1: Analyzing DNA. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp 83–248 [Google Scholar]

- Riethman HC, Moyzis RK, Meyne J, Burke DT, Olson MV (1989) Cloning human telomeric DNA fragments into Saccharomyces cerevesiae using a yeast artificial chromosome vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86:6240–6244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M, Hui L, Ma JL, Nusbaum HC, Clark K, Robinson L, Dziadzio L, et al (1997) Characterization of short tandem repeats from thirty-one human telomeres. Genome Res 7:917–923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouyer F, de la Chapelle A, Andersson M, Weissenbach J (1990) An interspersed repeated sequence specific for human subtelomeric regions. EMBO J 9:505–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccone S, De Sario A, Della Valle G, Bernardi G (1992) The highest gene concentrations in the human genome are in telomeric bands of metaphase chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:4913–4917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T (ed) (1989) Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- Sonnhammer E, Durbin R (1994) An expert system for processing sequence homology data. Proc Int Soc Mol Biol 94:363–368 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosi S, Scherer SW, Giudici G, Czepulkowski B, Biondi A, Kearney L (1999) Delineation of multiple deleted regions in 7q in myeloid disorders. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 25:384–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask BJ, Friedman C, Martin Gallardo A, Rowen L, Akinbami C, Blankenshi-J, Collins C, et al (1998) Members of the olfactory receptor gene family are contained in large blocks of DNA duplicated polymorphically near the ends of human chromosomes. Hum Mol Genet 7:13–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanGeel M, Heather LJ, Lyle R, Hewitt JE, Frants RR, deJong PJ (1999) The FSHD region on human chromosome 4q35 contains potential coding regions among pseudogenes and a high density of repeat elements. Genomics 61:55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vocero-Akbani A, Helms C, Wang JC, Sanjurjo FJ, Korte-Sarfaty J, Veile RA, Liu L, et al (1996). Mapping human telomere regions with YAC and P1 clones: chromosome-specific markers for 27 telomeres including 149 STSs and 24 polymorphisms for 14 proterminal regions. Genomics 36:492–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie AOM, Higgs DR, Rack KA, Buckle VJ, Spurr NK, Fischel-Ghodsian N, Ceccherini I, et al (1991) Stable length polymorphism of up to 260 kb at the tip of the short arm of human chromosome 16. Cell 64:595–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong ACC, Ning Y, Flint J, Clark K, Dumanski JP, Ledbetter DH, McDermid HE (1997) Molecular characterization of a 130-kb terminal microdeletion in a child with mild mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet 60:113–120 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Z, Hu XL, Flint J, Riethman HC (1999) A sequence-ready map of the human chromosome 17p telomere. Genomics 58:207–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]