Abstract

The MICs of six fluoroquinolones as well as minocycline and cefotaxime for 46 clinical isolates of Vibrio vulnificus were determined by the agar dilution method. All the drugs tested had good activities against all isolates, with the MICs at which 90% of the isolates tested were inhibited (MIC90s) by five of the fluoroquinolones ranging between 0.03 and 0.06 μg/ml. The MIC90 of lomefloxacin, on the other hand, was 0.12 μg/ml. Time-kill studies were conducted with these agents and a clinical strain of V. vulnificus, VV5823. When approximately 5 × 105 CFU of V. vulnificus/ml was incubated with any one of the above-mentioned six fluoroquinolones at concentrations of two times the MIC, there was an inhibitory effect on V. vulnificus that persisted for more than 48 h with no noted regrowth. The efficacies of the fluoroquinolones were further evaluated in vivo in the mouse model of experimental V. vulnificus infection and compared to the efficacy of a combination therapy using cefotaxime plus minocycline. With an inoculum of 1.5 × 107 CFU, 28 (87.5%) of 32 mice in the cefotaxime-minocycline-treated group survived and 29 (91%) of the 32 mice in the moxifloxacin-treated group survived while none of the 32 mice in the control group did. With an inoculum of 3.5 × 107 CFU, the difference in survival rates among groups of 15 mice treated with levofloxacin (13 of 15), moxifloxacin (10 of 15), gatifloxacin (10 of 15), sparfloxacin (11 of 15), ciprofloxacin (12 of 15), or lomefloxacin (10 of 15) was not statistically significant while none of the 15 mice treated with saline survived. We concluded that the newer fluoroquinolones as single agents are as effective as the cefotaxime-minocycline combination in inhibiting V. vulnificus both in vitro and in vivo.

Vibrio vulnificus is a halophilic, gram-negative bacillus recovered from estuarine and seawaters (15). Many cases of V. vulnificus infections have been reported from the coastal areas of the United States (1, 2, 16), Asia (4, 5, 24; Y. C. Chuang, Letter, Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:1072, 1992), and Europe (10, 18). The high prevalence of hepatitis B infections in areas such as Taiwan may also contribute to the high incidence of severe V. vulnificus infections. V. vulnificus characteristically produces three discernible syndromes (2, 4, 5, 20, 25): primary sepsis, wound infection, and gastrointestinal illness. The mortality rates are up to 55% in septic patients and 25% in those with wound infections (5).

Most of the V. vulnificus isolates are susceptible in vitro to a variety of antibiotics (1, 3, 11, 13, 14; P. R. Hsueh, J. C. Chang, S. C. Chang, S. W. Ho, and W. C. Hsieh, Letter, Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 14:151-153, 1995). Tetracycline has been recommended as the antimicrobial agent of choice for the treatment of V. vulnificus infection because of the effectiveness of tetracycline for V. cholerae infections. More recently, our in vitro study showed that a combination of cefotaxime and minocycline had a synergistic effect against V. vulnificus (6). A further in vivo study showed that therapy with a combination of cefotaxime and minocycline is more advantageous than single-drug regimens with these agents for the treatment of severe experimental murine V. vulnificus infection (9). Ciprofloxacin has also been used successfully for the treatment of V. vulnificus wound infections (M. C. Meadors and G. A. Pankey, Letter, J. Infect. 20:88-89, 1990). In general, the newer fluoroquinolones developed over the past few years have greater potency, a broader spectrum of antimicrobial activity, greater in vitro efficacy against resistant organisms, and a better safety profile than other antimicrobial agents. Moreover, step-down therapy, a cost-saving alternative, has been claimed to be advantageous. For this reason, the activities of the new fluoroquinolones against V. vulnificus were evaluated in the present study both in vitro and in vivo in comparison with that of cefotaxime-minocycline.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Determination of the MICs of cefotaxime, minocycline, and six newer fluoroquinolones for 46 clinical isolates of V. vulnificus.

Clinical isolates of V. vulnificus were collected from Chi Mei Foundation Medical Center, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, and the National Taiwan University Hospital. These strains were originally isolated from blood or from wound or bullous fluid. All isolates were identified as V. vulnificus by conventional methods, as described previously (6). The organisms were stored at −70°C in Protect bacterial preservers (Technical Service Consultants Limited, Heywood, Lancashire, England) before being cultured on Luria-Bertani agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). V. vulnificus VV5823, originally isolated from a septicemic patient at National Cheng Kung University Hospital, was arbitrarily selected for both the time-kill and the in vivo studies. The MICs of the following antibiotics were determined by the agar dilution method as previously described (22): cefotaxime (Hoechst AG, Frankfurt, Germany), minocycline (American Cyanamid Co., Pearl River, N.Y.), moxifloxacin (Bayer AG, Frankfurt, Germany), gatifloxacin (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Humacao, Australia), sparfloxacin (Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan), levofloxacin (Daiichi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), ciprofloxacin (Bayer AG), and lomefloxacin (Shionogi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). The drugs were incorporated into the agar in serial twofold concentrations as follows: minocycline, 0.03 to 128 μg/ml; ciprofloxacin, 0.03 to 16 μg/ml; lomefloxacin, 0.03 to 16 μg/ml; moxifloxacin, 0.03 to 64 μg/ml; gatifloxacin, 0.03 to 128 μg/ml; cefotaxime, 0.03 to 64 μg/ml; sparfloxacin, 0.03 to 16 μg/ml; and levofloxacin, 0.03 to 16 μg/ml. The fluoroquinolone powder was dissolved in 0.05 M NaOH solution and diluted with sterile water to the required test concentration. The minocycline powder was dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH solution instead, while the cefotaxime was dissolved in sterile water to the required test concentration. The MIC was defined and the bacterial inocula were prepared as previously described (6), except that final inocula of approximately 104 CFU per spot of inoculum were applied to the plates and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used in each run as a control for susceptibility testing.

Determination by time-kill studies of the inhibitory effect of the cefotaxime-minocycline combination and six newer fluoroquinolones on V. vulnificus.

Bacterial concentrations were diluted in 125-ml conical glass flasks to around 5.0 × 105 CFU/ml in 25 ml of fresh Mueller-Hinton broth. Cefotaxime, minocycline, and the six newer fluoroquinolones were prepared and placed in flasks at the following concentrations: cefotaxime and minocycline, 0.03 μg/ml each; moxifloxacin, 0.015, 0.03, 0.06, 0.075, 0.09, and 0.12 μg/ml; gatifloxacin, 0.015, 0.03, 0.06, 0.075, 0.09, and 0.12 μg/ml; sparfloxacin, 0.015, 0.03, 0.06, 0.075, 0.09, and 0.12 μg/ml; levofloxacin, 0.075, 0.015, 0.03, 0.06, 0.075, and 0.09 μg/ml; ciprofloxacin, 0.015, 0.03, 0.045, 0.06, 0.075, and 0.09 μg/ml; and lomefloxacin, 0.06, 0.09, 0.12, 0.18, 0.25, and 0.36 μg/ml. Each flask was incubated under the aforementioned conditions. Duplicate samples were removed for determination of CFU at specified time intervals as described previously (6), except that Luria-Bertani agar plates were used and incubated at 37°C overnight. All the experiments were performed at least twice for confirmation of the results.

In vivo efficacies of combined cefotaxime-minocycline treatment and of six newer fluoroquinolones against experimental V. vulnificus infection in mice.

The marketed parenteral forms of cefotaxime, minocycline, and ciprofloxacin used in in vivo experiments were provided by Hoechst Taiwan Co., Ltd., Lederle Parenterals, Inc. (Carolina, Puerto Rico), and Bayer AG, respectively. Parenteral forms of moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, gatifloxacin, sparfloxacin, and lomefloxacin were not available in Taiwan, so their standard powders were diluted to the desired concentration for the experiments. Antibiotics were freshly diluted in sterile 0.85% saline on the morning of the day the experiment was conducted and delivered in sterile disposable plastic syringes.

The clinical isolate V. vulnificus VV5823 was used throughout the study. The bacterial inocula were prepared as previously described (9). Five- to six-week-old female inbred BALB/c mice (Animal Center, National Science Council, Taipei, Taiwan) weighing 20 g on average were used throughout the study. An inoculum size of 107 CFU was chosen for the animal experiments because large inoculum size was proven in our previous report to be more discriminatory for evaluation of the efficacy of the treatment regimens (9). In experiment 1, 1.5 × 107 CFU of V. vulnificus was injected subcutaneously at a point over the right thigh of each mouse. There were three groups, including the control, the cefotaxime-minocycline-treated, and the moxifloxacin-treated groups, with 32 mice in each group. Cefotaxime, minocycline, or moxifloxacin was given intraperitoneally in a 0.1-ml volume, beginning 2 h after the animal was infected. The doses of antibiotics were determined according to the recommendations of the pharmaceutical companies. A 30-mg dose of cefotaxime/kg of body weight was given every 6 h, and a loading dose of 4 mg of minocycline/kg followed by a maintenance dose of 2 mg of minocycline/kg was given every 12 h. The dose of moxifloxacin was as follows: a loading dose of 16 mg/kg, followed by a maintenance dose of 8 mg/kg every 24 h. Control animals received 0.1 ml of sterile 0.85% saline every 6 h. Antibiotics were given for a total of 42 h. The numbers of surviving mice were recorded at 6-h intervals beginning after the initial treatment and ending 120 h after treatment began. For humanitarian reasons, animals were euthanized when they were moribund even though they were still breathing. The experimental design of experiment 2 was identical to that of experiment 1 except that inocula of 3.5 × 107 CFU of V. vulnificus VV5853 were used and animals were treated for a total of 36 h. There were seven groups of 15 mice each, including six groups treated with fluoroquinolones and a saline-treated control group. The doses of the newer fluoroquinolones were as follows: for moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, and gatifloxacin, a loading dose of 16 mg/kg of body weight followed by a maintenance dose of 8 mg/kg every 24 h; for sparfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and lomefloxacin, loading doses of 10, 16, and 8 mg/kg, respectively, followed by maintenance doses of 5, 8, and 4 mg/kg, respectively, every 12 h. The antibiotics were given for a total of 36 h. The animal experiments have complied with all relevant national guidelines of the Republic of China and with the Chi Mei Foundation Medical Center Animal Use Policy.

RESULTS

MICs.

All antibiotics tested showed good in vitro activity against all isolates. The MICs at which 90% of the isolates were inhibited (MIC90s) by levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin were 0.03 μg/ml, and those of minocycline, cefotaxime, moxifloxacin, sparfloxacin, and gatifloxacin were 0.06 μg/ml. The MIC90 of lomefloxacin, on the other hand, was 0.12 μg/ml. The MICs of minocycline, cefotaxime, moxifloxacin, gatifloxacin, sparfloxacin, levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and lomefloxacin for strain VV5853 were 0.06, 0.06, 0.06, 0.03, 0.06, 0.03, 0.03, and 0.12 μg/ml, respectively.

Determination of the inhibitory effect of combined cefotaxime-minocycline treatment and of six newer fluoroquinolones on V. vulnificus in time-kill kinetics.

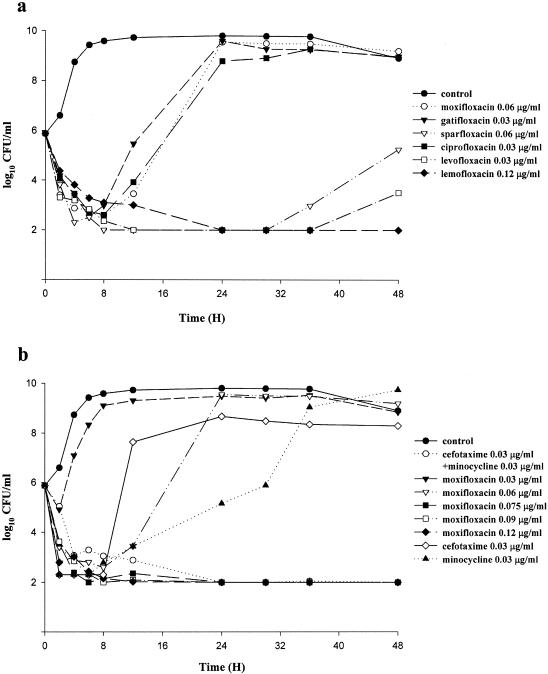

When approximately 5 × 105 CFU of V. vulnificus/ml was incubated with gatifloxacin, moxifloxacin, ciprofloxacin, sparfloxacin, and levofloxacin at MICs, the bacterial growth was inhibited during the initial 6, 8, 8, 12, and 36 h, respectively, and thereafter, V. vulnificus regrew (Fig. 1a). When subinhibitory concentrations of cefotaxime (0.03 μg/ml, one-half the MIC) and minocycline (0.03 μg/ml, one-half the MIC) were combined in the same culture, the inhibitory effect on V. vulnificus persisted for more than 48 h with no regrowth noted (Fig. 1b). The same result was observed when the following drugs were used at the concentrations indicated: moxifloxacin, 0.075 μg/ml (five-fourths the MIC) (Fig. 1b); gatifloxacin, 0.06 μg/ml (two times the MIC) (data not shown); sparfloxacin, 0.09 μg/ml (five-fourths the MIC); levofloxacin, 0.045 μg/ml (one and a half times the MIC); ciprofloxacin, 0.06 μg/ml (two times the MIC); and lomefloxacin, 0.12 μg/ml (MIC) (Fig. 1a). The MICs of sparfloxacin, levofloxacin, and lomefloxacin were equivalent to the minimal bactericidal concentrations of these drugs (Fig. 1a).

FIG. 1.

(a) Inhibition of growth curves of V. vulnificus VV5823 (inoculum size, 5 × 105 CFU/ml) after incubation with different fluoroquinolones at MICs. The lower limit of detection was set at 10 colonies (100 CFU/ml). (b) Inhibition of growth curves of V. vulnificus VV5823 (inoculum, 5 × 105 CFU/ml) after incubation with minocycline, cefotaxime alone, a combination of cefotaxime and minocycline, or different concentrations of moxifloxacin. MICs of cefotaxime, minocycline, and moxifloxacin were 0.06 μg/ml.

In vivo study.

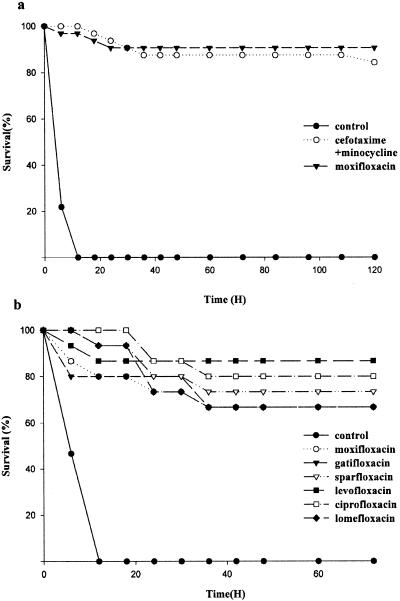

In experiment 1, with an inoculum of 1.5 × 107 CFU, all the mice in the control group died within 12 h (Fig. 2a). The survival rates recorded at the end of the experiment were 87.5 and 91% for the minocycline-cefotaxime-treated group and the moxifloxacin-treated group, respectively. Both antibiotic-treated groups had significantly higher survival rates than the saline-treated group (P < 0.001, by log rank test), while the difference between the two antibiotic-treated groups was insignificant. In experiment 2, with an inoculum of 3.5 × 10 7 CFU and antibiotic treatment for 36 rather than 42 h, survival rates among mice treated with the fluoroquinolones (13, 10, 10, 11, 12, and 10 out of 15 mice in levofloxacin-, moxifloxacin-, gatifloxacin-, sparfloxacin-, ciprofloxacin-, and lomefloxacin-treated groups, respectively) were significantly higher than that of the saline-treated control group (0 of 15) (P < 0.01, log rank test) but not significantly different from each other (Fig. 2b).

FIG. 2.

(a) Survival rates of mice (n = 15) subcutaneously injected with 1.5 × 107 CFU of V. vulnificus following treatment with a cefotaxime-minocycline combination, moxifloxacin, or saline. The differences between moxifloxacin- and saline-treated groups and between cefotaxime-minocycline-treated and saline-treated groups were significant (P < 0.001) by log rank test, while that between cefotaxime-minocycline-treated and moxifloxacin-treated groups was not significant. (b) With an inoculum of 3.5 × 10 7 CFU and antibiotic treatment for 36 rather than 42 h, survival rates among mice (n = 15) treated with the fluoroquinolones were significantly higher than that of the saline-treated control group (P < 0.01, log rank test) but not significantly different from one another.

DISCUSSION

The results show that minocycline, cefotaxime, and a variety of newer fluoroquinolones have good in vitro activities against all the clinical isolates of V. vulnificus. The MIC90s were as low as 0.03 μg/ml. In the time-kill studies, there was no significant difference in antibacterial effects among the six newer fluoroquinolones. At concentrations less than or equal to two times the MIC, the inhibitory effects of all the newer fluoroquinolones persisted for more than 48 h, with no regrowth noted. These findings indicate that the fluoroquinolones are generally bactericidal, with a very small minimal bactericidal concentration/MIC ratio. These inhibitory activities are as effective as that of the combination of cefotaxime and minocycline, which were shown in the previous study to have a synergistic effect against V. vulnificus (6). The in vivo study shows that newer fluoroquinolones alone have the same efficacy as the combination of cefotaxime and minocycline in the treatment of severe experimental murine V. vulnificus infection. Based on the time-kill results, it would appear that levofloxacin is the most active. This also appears to be the case in the in vivo study, although the differences in activities among the various fluoroquinolones are not statistically significant.

Because of the sporadic occurrence of V. vulnificus infections, there are virtually no randomized clinical trials to determine which antibiotic is most effective for treatment. Morris and Tenney (20; J. G. Morris, Jr., and J. Tenney, Letter, JAMA 253:1121-1122, 1985) stressed the superiority of tetracycline over cefotaxime based on the study of a mouse model conducted by Bowdre et al. (3). Fang (F. C. Fang, Letter, Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:1071-1072, 1992) advocated the use of tetracycline to treat V. vulnificus infections because an antibiotic which inhibits protein synthesis was thought to be preferable to one which damages the cell wall and may cause the release of an increased level of toxic microbial proteins. On the other hand, other reports of clinical experiences suggest that the expanded-spectrum cephalosporins may be superior to tetracycline for treating V. vulnificus infections (5; Chuang, letter). A previous in vitro study showed the synergistic effect of cefotaxime and minocycline against V. vulnificus (6). A further in vivo study showed that therapy with a combination of cefotaxime and minocycline was more efficacious than single-drug therapy with these antibiotics for the treatment of severe experimental murine V. vulnificus infection (9).

The mouse model of V. vulnificus infection used in the present study was previously shown to cause necrotizing fasciitis, bacteremia, and death within 24 h, mimicking V. vulnificus bacteremia in humans (7). V. vulnificus can produce mutiple extracellular cytolytic or cytotoxic toxins and enzymes that are associated with extensive tissue damage and may play a major role in the development of sepsis (7, 8, 12, 17, 19, 23). More than 50% of cases of V. vulnificus infections lead to either primary or secondary severe soft tissue involvement manifesting as hemorrhagic bullae or necrotizing fasciitis (5, 16). The clinical course of V. vulnificus infection in a septicemic patient is fulminant, and over 50% of such patients die within 48 h of hospitalization (5, 16). The skin manifestations usually develop at the time of admission or within 24 h of hospitalization. This condition can worsen rapidly, within hours (5). In the case of severe wound infection, especially in necrotizing fasciitis, widespread obliterative vasculitis and vascular necrosis are the major features of the skin lesion and can seriously compromise the blood supply. An antibiotic with good tissue penetration ability is urgently needed in these clinical situations. Müller et al. showed that moxifloxacin was promising in the treatment of skin and soft tissue infections (21). This is because the drug concentrations attained in the fluid in the interstitial spaces in humans and in skin blisters following a single dose of 400 mg exceeded the MIC90s for most clinical isolates (22). The unique site of action and the good tissue penetration abilities of the newer fluoroquinolones may be related to their efficacy in clinical use. In view of the difference in pharmacokinetic parameters between mice and humans, the question of whether or not all the results of animal model studies can be extrapolated in clinical situations has yet to be answered.

Taken together and in comparison to a combination of cefotaxime and minocycline, the newer fluoroquinolones, such as levofloxacin, are potentially useful as monotherapy for severe V. vulnificus soft tissue infections. Further clinical trials with these agents in treating human V. vulnificus infections are warranted.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anthony W. Chow for his critical review of this article.

This work was partly supported by grants (DOH-91-DC-1015, CMFHR 9116) from the Center for Disease Control, the Department of Health, and Chi Mei Medical Center, Tainan, Taiwan, Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blake, P. A., M. H. Merson, R. E. Weaver, D. G. Hollis, and P. C. Heublein. 1979. Disease caused by a marine Vibrio: clinical characteristics and epidemiology. N. Engl. J. Med. 300:1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonner, J. R., A. S. Coker, C. R. Berryman, and H. M. Pollock. 1983. Spectrum of vibrio infections in a gulf coast community. Ann. Intern. Med. 99:464-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowdre, J. H., J. H. Hull, and D. M. Cocchetto. 1983. Antibiotic efficacy against Vibrio vulnificus in the mouse: superiority of tetracycline. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 225:595-598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chuang, Y. C., C. Young, and C. W. Chen. 1989. Vibrio vulnificus infection. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 21:721-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chuang, Y. C., C. Y. Yuan, C. Y. Liu, C. K. Lan, and A. H. M. Huang. 1992. Vibrio vulnificus infection in Taiwan: report of 28 cases and review of clinical manifestations and treatment. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:271-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chuang, Y.-C., J.-W. Liu, W.-C. Ko, K.-Y. Lin, J.-J. Wu, and K.-Y. Huang. 1997. In vitro synergism between cefotaxime and minocycline against Vibrio vulnificus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2214-2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chuang, Y. C., H. M. Sheu, W. C. Ko, T. M. Chang, M. C. Chang, and K. Y. Huang. 1997. Mouse skin damage caused by a recombinant extracellular metalloprotease from Vibrio vulnificus and by V. vulnificus infection. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 96:677-684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chuang, Y. C., T. M. Chang, and M. C. Chang. 1997. Cloning and characterization of the gene (empV) encoding extracellular metalloprotease from Vibrio vulnificus. Gene 189:163-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuang, Y.-C., W.-C. Ko, S.-T. Wang, J.-W. Liu, C.-F. Kuo, J.-J. Wu, and K.-Y. Huang. 1998. Minocycline and cefotaxime in the treatment of experimental murine Vibrio vulnificus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1319-1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalsgaard, A., N. Frimodt-Møller, B. Bruun, L. H/oi, and J. L. Larsen. 1996. Clinical manifestations and molecular epidemiology of Vibrio vulnificus infections in Denmark. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 15:227-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.French, G. L., M. L. Woo, Y. W. Hui, and K. Y. Chan. 1989. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of halophilic vibrios. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 24:183-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray, L. D., and A. S. Kreger. 1989. Detection of Vibrio vulnificus cytolysin in V. vulnificus-infected mice. Toxicon 27:439-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkins, R. D., and J. M. Johnston. 1986. Inland presentation of Vibrio vulnificus primary septicemia and necrotizing fasciitis. West. J. Med. 144:78-80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly, M. T., and D. M. Avery. 1980. Lactose-positive Vibrio in seawater: a cause of pneumonia and septicemia in a drowning victim. J. Clin. Microbiol. 11:278-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly, M. T., F. W. Hickman-Brenner, and J. J. Farmer III. 1991. Vibrio, p. 384-395. In A. Balows, W. J. Hausler, Jr., K. L. Herrmann, H. D. Isenberg, and H. J. Shadomy (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 5th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 16.Klontz, K. C., S. Lieb, M. Schreiber, H. T. Janowski, L. M. Baldy, and R. A. Gunn. 1988. Syndromes of Vibrio vulnificus infections: clinical and epidemiologic features in Florida cases, 1981-1987. Ann. Intern. Med. 109:318-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linkous, D. A., and J. D. Oliver. 1999. Pathogenesis of Vibrio vulnificus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 174:207-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melhus, Å., T. Holmahl, and I. Tjernberg. 1995. First documented case of bacteremia with Vibrio vulnificus in Sweden. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 27:81-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyoshi, S. I., Y. Hirata, K. I. Tomochika, and S. Shinoda. 1994. Vibrio vulnificus may produce a metalloprotease causing an edematous skin lesion in vivo. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 121:321-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris, J. G., Jr., and R. E. Black. 1985. Cholera and other vibrioses in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 312:343-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Müller, M., H. Staß, M. Brunner, J. G. Möller, E. Lackner, and H. G. Eichler. 1999. Penetration of moxifloxacin into peripheral compartments in humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2345-2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1999. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed. Approved standard M7-A4. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 23.Oliver, J. D., J. E. Wear, M. B. Thomas, M. Warner, and K. Linder. 1986. Production of extracellular enzymes and cytotoxicity by Vibrio vulnificus. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 5:99-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park, S. D., H. S. Shon, and N. J. Joh. 1991. Vibrio vulnificus septicemia in Korea: clinical and epidemiologic findings in seventy patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 24:397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tacket, C. O., F. Brenner, and P. A. Blake. 1984. Clinical features and an epidemiological study of Vibrio vulnificus infections. J. Infect. Dis. 149:558-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]