Abstract

We determined the target enzyme interactions of garenoxacin (BMS-284756, T-3811ME), a novel desfluoroquinolone, in Staphylococcus aureus by genetic and biochemical studies. We found garenoxacin to be four- to eightfold more active than ciprofloxacin against wild-type S. aureus. A single topoisomerase IV or gyrase mutation caused only a 2- to 4-fold increase in the MIC of garenoxacin, whereas a combination of mutations in both loci caused a substantial increase (128-fold). Overexpression of the NorA efflux pump had minimal effect on resistance to garenoxacin. With garenoxacin at twice the MIC, selection of resistant mutants (<7.4 × 10−12 to 4.0 × 10−11) was 5 to 6 log units less than that with ciprofloxacin. Mutations inside or outside the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDR) of either topoisomerase IV, or gyrase, or both were selected in single-step mutants, suggesting dual targeting of topoisomerase IV and gyrase. Three of the novel mutations were shown by genetic experiments to be responsible for resistance. Studies with purified topoisomerase IV and gyrase from S. aureus also showed that garenoxacin had similar activity against topoisomerase IV and gyrase (50% inhibitory concentration, 1.25 to 2.5 and 1.25 μg/ml, respectively), and although its activity against topoisomerase IV was 2-fold greater than that of ciprofloxacin, its activity against gyrase was 10-fold greater. This study provides the first genetic and biochemical data supporting the dual targeting of topoisomerase IV and gyrase in S. aureus by a quinolone as well as providing genetic proof for the expansion of the QRDRs to include the 5′ terminus of grlB and the 3′ terminus of gyrA.

Two type II topoisomerases, DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, which are both involved in bacterial DNA synthesis, are the major targets of quinolones (11, 17). DNA gyrase is composed of two GyrA and two GyrB subunits, and topoisomerase IV is composed of two ParC and two ParE (in Staphylococcus aureus named GrlA and GrlB, respectively) subunits. One of the principal mechanisms of resistance to quinolones is that of point mutations in the genes encoding the target enzymes. These point mutations have classically been identified in distinct regions of gyrase and topoisomerase IV, named the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs), which are located at the 5′ terminus of gyrA and parC (grlA in S. aureus) and midportions of gyrB and parE (grlB in S. aureus) (21). Fluoroquinolones differ in their relative activities against these enzymes. A mutation in the more sensitive enzyme results in an increase in the MIC of a fluoroquinolone, whereas a mutation in the less sensitive enzyme generally causes resistance only in the presence of resistance mutations in the primary target (23, 41). A quinolone with similar affinities for both targets is little affected by a mutation in one of the enzymes, and concurrent mutations in both enzymes are necessary for resistance to develop. Although all fluoroquinolones have been reported to target DNA gyrase in gram-negative bacteria, the target can be either DNA gyrase or topoisomerase IV or in some cases both in Streptococcus pneumoniae (14, 19, 36-38, 47). Until recently, all the studied quinolones have been reported to have topoisomerase IV as their primary target in S. aureus (10, 11, 24, 25, 34, 52). Recently, nadifloxacin, a topical quinolone used in Japan, has been reported to select for first-step gyrase mutants (45), suggesting that gyrase is its primary target in S. aureus.

Since the introduction of the first member of the quinolone antimicrobial agents, nalidixic acid, the molecular structures of the quinolones have been extensively modified, with one of the aims being enhanced activity against a broad range of organisms (2). The potency of the first quinolones was greatly enhanced by the addition of a fluorine at position 6, which became a classical addition to the quinolone ring; until recently, research has focused largely on modifications at other positions of the fluoroquinolone ring (2, 7). However, garenoxacin is a novel des-fluoro(6) quinolone that lacks the classical C-6 fluorine and has a difluoromethoxy substituent at position 8, instead of a methoxy group, which has been shown to improve bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity and decrease the selection of resistant mutants (24, 25, 32, 55, 56). Garenoxacin has exceptional activity against gram-positive cocci including S. aureus (4, 16, 28); it is the most active quinolone against methicillin-susceptible and -resistant staphylococci, being more active than moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin (16), and it is 16- to >64-fold more active than ciprofloxacin against quinolone-resistant S. aureus (44). It is also highly selective for bacterial versus eukaryotic topoisomerases and has activity similar to that of ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin against S. aureus topoisomerase IV in assays of inhibition of DNA decatenation activity (31).

Given the activity of garenoxacin against S. aureus and its novel structure, we sought to determine its mechanism of action against this pathogen. We studied the effects of mutations in either DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV on the activity of garenoxacin by determining its activity against genetically defined strains of S. aureus, determining the frequency of selection of resistant mutants, and characterizing these mutants. Purified topoisomerase IV and gyrase from wild-type S. aureus and topoisomerase IV from a GrlA mutant were used to study and compare the inhibition of these enzymes by garenoxacin and ciprofloxacin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are shown in Table 1. Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium, and S. aureus strains were grown in brain heart infusion medium. All strains were grown at 37°C except for S. aureus strains with the thermosensitive plasmids derived from pCL52.2, which were grown at 30°C. Spectinomycin and ampicillin were used at 50 μg/ml, and tetracycline was used at 5 μg/ml, except during integration of plasmid pCL52.2 into the chromosome, when it was used at 3 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotypea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. aureus | ||

| ISP794 | 8325 pig-131 | 43 |

| MT5 | 8325 nov (gyrB142) hisG15 pig-131 | 46 |

| SS1 | 8325 pig-131 nov (gyrB142) gyrA (Ser84Leu) | 3 |

| MT5224c2 | 8325 nov (gyrB142) hisG15 pig-131 grlA552 | 34 |

| MT5224c3 | 8325 nov (gyrB142) hisG15 pig-131 grlA547 | 46 |

| MT111 | 8325 pig-131 grlA548 | 46 |

| MT5224c4 | 8325 nov (gyrB142) hisG15 pig-131 grlA542 (Ser80Phe) | 46 |

| MT5224c9 | 8325 nov (gyrB142) hisG15 pig-131 grlB543 (Asn470Asp) | 46 |

| MT23142 | 8325 pig-131 flqB Ω(chr::Tn916) 1108 | 34 |

| EN1252a | 8325 nov (gyrB142) hisG15 pig-131 grlA542 gyrA Ω1051 (Erm) Nov+ | 3 |

| P4 | ISP794 grlA563 (Arg43Cys) | 24 |

| P10 | ISP794 grlA555 (Ala176Thr) | 24 |

| P21 | ISP794 grlA556 (Asp69Tyr) | 24 |

| GB | ISP794 grlB560 (Pro25His) | 25 |

| B2 | ISP794 gyrA (Ser784Tyr) | This study; spontaneous garenoxacinr |

| B15 | ISP794 gyrA (Ser84Tyr) | This study; spontaneous garenoxacinr |

| B23 | ISP794 grlB564 (Asp33Tyr) gyrA (Arg530His) | This study; spontaneous garenoxacinr |

| B26 | ISP794 grlA565 (Thr292Ile) | This study; spontaneous garenoxacinr |

| BS1 | ISP794 (unidentified mutation) | This study; serial-passage mutant |

| BS2 | ISP794 gyrB (Gly486Val) | This study; serial-passage mutant |

| BS3 | ISP794 gyrB (Gly486Val) | This study; serial-passage mutant |

| BS4 | ISP794 gyrA (Ser84Leu) gyrB (Gly486Val) | This study; serial-passage mutant |

| BS5 | ISP794 gyrA (Ser84Leu) gyrB (Gly486Val) | This study; serial-passage mutant |

| BS6 | ISP794 grlA (Ser80Phe) gyrA (Ser84Leu) gyrB (Gly486Val) | This study; serial-passage mutant |

| DIB2 | ISP794 gyrA (Ser784Tyr) | This study; allelic exchange mutant |

| DIB23B | ISP794 grlB564 (Asp33Tyr) | This study; allelic exchange mutant |

| DIB23BA | ISP794 grlB564 (Asp33Tyr) gyrA (Arg530His) | This study; allelic exchange mutant |

| SS1B23B | ISP794 nov (gyrB142) gyrA (Ser84Leu) grlB564 (Asp33Tyr) | This study; allelic exchange mutant |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F− φ80d lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF) U169 deoR recA1 endA1 phoA hsdR17 (rK− mK−) supE44λ−thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | GIBCO-BRL |

| Plasmids | ||

| PGEM3-zf(+) | 3,199-bp cloning vector, Apr | Promega |

| pCL52.2 | 8,119-bp plasmid containing the replicon of pGB2, Spr (E. coli) and temperature-sensitive replicon of pE194, Tcr | 42 |

| PTrcHis A,B, and C | 4.4-kb expression vector, Apr | Invitrogen |

Abbreviations: Ap, ampicillin; Sp, spectinomycin; Tc, tetracycline.

Drug susceptibility determinations.

Garenoxacin was kindly provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., and ciprofloxacin was kindly provided by Bayer Corp. Nalidixic acid, novobiocin, and ethidium bromide were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). MICs were determined in duplicate at least twice on Trypticase soy agar containing serial twofold dilutions of antibiotics, and growth was scored after 24 and 48 h of incubation at 37°C. MICs of nalidixic acid were used to screen for gyrA mutations, MICs of novobiocin were used to screen for grlB mutations (12), and MICs of ethidium bromide were used to screen for NorA overexpression (29). In genetic tests when twofold differences were encountered, they were confirmed by repetitive testing.

Frequency of selection of mutants.

Mutants were selected by plating appropriate dilutions of overnight cultures of S. aureus ISP794 on brain heart infusion agar without any antibiotic or with garenoxacin or ciprofloxacin at concentrations one-, two-, four-, and eightfold the MIC of each drug. For selection with garenoxacin, large (150- by 15-mm) petri dishes were used to plate 1011 to 1012 CFU. Each plating was done in duplicate and repeated at least twice. Selection plates were incubated at 37°C. The frequency of selection of resistant mutants was calculated as the ratio of the number of resistant colonies at 48 h to the number of cells inoculated. Selected colonies were subcultured once on brain heart infusion agar plates containing the selecting concentration of garenoxacin and, if necessary, once more on brain heart infusion agar without any antibiotic and then stored at −70°C in 10% glycerol in brain heart infusion broth.

Stepwise selection of resistant mutants.

S. aureus ISP794 was serially passaged on brain heart infusion agar containing twofold-increasing concentrations of garenoxacin to define the highest level of resistance achievable. Selection began at the MIC of garenoxacin for ISP794. At each step, several mutant colonies were subcultured on brain heart infusion agar plates containing the selecting concentration of garenoxacin before being stored at −70°C and passaged at a twofold higher antibiotic concentration.

Sequence analysis.

Chromosomal DNA from various single-step and multiple-step mutants of S. aureus ISP794 was isolated using the Easy-DNA kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) after lysing the cells with lysostaphin (Ambi, Lawrence, N.Y.) at 0.1 mg/ml and was used as a template for PCRs. PCR amplification for the QRDRs of grlA, grlB, gyrA, gyrB, and the promoter region of norA was performed using Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.). PCR amplification for the QRDR of grlA was performed with previously published primers to encompass codons 23, 157, and 176, mutations that have been associated with quinolone resistance (24, 25). DNA sequencing of the PCR products was performed with the ABI Fluorescent System and Taq dye terminators (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). For strains in which no mutation was found in these regions, the entirety of the grlA, grlB, gyrA, and gyrB genes was amplified by PCR and sequenced by the same method.

Cloning and allelic exchange.

A 1,096-bp internal fragment of grlA was amplified by PCR with the upstream primer containing an engineered EcoRI site (5′-GAAGGAATTCAAGCAACAC-3′) (5′ nucleotide at position 2931 in the sequence published by Yamagishi et al. [52]) and the downstream primer containing an engineered BamHI site (5′-CTGGATCCGTATCTTGCGT-3′ (5′ nucleotide at position 4026). An annealing temperature of 50°C and an extension time of 70 s were used for this PCR. The primers and PCR conditions used to amplify a 652-bp internal fragment of grlB together with a 378-bp upstream region have been published previously (25). The entire gyrA gene was also amplified using primers with engineered EcoRI and BamHI sites (5′-GAGGAATTCTTGATGGCTGA-3′) (5′ nucleotide at position 2140 in the sequence published by Ito et al. [26]) and 5′-GTCTGGATCCTTATTATTCTTCATCTG-3′ (5′ nucleotide at position 4828), and the entire gyrB gene was amplified using primers with engineered BamHI and PstI sites (5′-TCATGGATCCCGCTAAATTGTAT-3′) (5′ nucleotide at position 119 in the sequence published by Ito et al. [26]) and 5′-CCATCTGCAGCCATTGAACCA-3′ (5′ nucleotide at position 2501). PCR conditions for gyrA and gyrB included annealing temperatures of 52 and 56°C and extension times of 170 and 150 s, respectively. PCR products were purified after gel extraction by using the Compass kit (American Bioanalytical, Natick, Mass.) and ligated into the EcoRI and BamHI or BamHI and PstI sites of pGEM3-zf(+). Recombinant plasmids were electroporated into E. coli DH5α. The insert for each mutant was sequenced to confirm that new mutations were not introduced by the DNA polymerase. The inserts were then ligated into pCL52.2, a thermosensitive shuttle vector, and the plasmids were again electroporated into E. coli DH5α, followed by electroporation to RN4220 and ISP794, as previously described (35). Allelic exchange was performed as previously described (24, 25). The resultant colonies were screened for susceptibility to tetracycline (MIC, ≤3 μg/ml) and change in susceptibility to garenoxacin (MIC, >0.064 μg/ml) or ciprofloxacin (MIC, >0.25 μg/ml). The MICs of ciprofloxacin and garenoxacin were determined for colonies that were tetracycline susceptible and had a changed susceptibility to garenoxacin or ciprofloxacin. Direct DNA sequencing of the PCR product of the appropriate region amplified from chromosomal DNA was used to confirm the presence of the expected mutations.

Plasmids expressing grlA, grlB, gyrA, and gyrB.

Vent polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) was used to amplify the grlA, grlB, gyrA, and gyrB genes from the wild-type strain, ISP794, as well as the grlA gene from the grlA mutant with the Ser80Phe mutation, MT5224c4. For amplification of grlA, the forward primer contained an engineered BamHI site and the reverse primer contained an engineered EcoRI site (5′-AAAAAAGGATCCTAGTGAGTGAAATA-3′ and 5′-AAAGAATTCCGTGATTGCATATAGTTTTTA-3′, respectively); for amplification of grlB, the forward primer contained an engineered XhoI site and the reverse primer contained an engineered EcoRI site (5′-GAAATCACTCGAGATGAATAAACA-3′ and 5′-GAATGAATTCACTCACTAGATTTCC-3′, respectively). The forward primer used for amplification of gyrA contained an engineered BamHI site (5′-GGAGGATCCCTTGATGGCTGAA-3′), and the reverse primer contained an engineered EcoRI site (5′-TTAGAATTCTTCATCTGATGATTGT-3′). Primers for gyrB amplification contained engineered BamHI and HindIII sites, respectively (forward primer, 5′-AAAGTAACAGGATCCGATGGTGAC-3′; reverse primer, 5′-AAAAAGCTTAGCGCTTAGAAGTCT-3′). PCR conditions were an initial denaturation at 94°C for 10 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 45 s, annealing at 53°C (for grlA and grlB), 49°C (for gyrA), or 52°C (gyrB) for 45 s, and extension at 72°C for 160 s (for grlA and gyrA), 135 s (for grlB), or 130 s (for gyrB); followed by a final extension of 10 min at 72°C. PCR products were gel extracted using the Compass kit, digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes, and ligated into appropriately digested expression vectors pTrcHis A, B or C (Invitrogen), for expression of recombinant proteins containing N-terminal His6 tags in E. coli. For cloning of grlA, pTrcHis C was used; for grlB, pTricHis A was used; and for gyrA and gyrB, pTricHis B was used. The resultant plasmids were electroporated into E. coli DH5α, and the inserts were sequenced to confirm correct nucleotide sequence as well as proper placement in the recombinant plasmids.

Protein overexpression and purification.

A sample (200 μl) of an overnight culture of E. coli DH5α with the recombinant plasmids in Luria-Bertani broth plus 50 μg of ampicillin per ml was used to inoculate 50 ml of fresh medium with the same antibiotic concentration. The cells were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 (mid-logarithmic phase), induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at a final concentration of 1 mM, and harvested by centrifugation at 4°C following 3 h of growth in the presence of IPTG. The cell pellets were resuspended in 6 ml of 1× phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and stored at −70°C until used for protein isolation. Isolation was carried out with the HisTrap kit (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.) as recommended by the manufacturer. The suspensions were thawed on ice, and lysozyme and Brij were added to final concentrations of 0.02 and 0.12%, respectively. Incubation was continued at 4°C for 30 min. Following centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min, the supernatant was filter sterilized using a 0.45-μm-pore-site filter and loaded on a nickel iminodiacetic acid-Sepharose column previously washed with 10 ml of Start buffer (1× phosphate buffer containing 10 mM imidazole [pH 7.4]). The column was again washed with 10 ml of Start buffer. The histidine-tagged GrlA, GrlB, GyrA, and GyrB proteins were eluted with increasing concentrations of imidazole, each in 5 ml of 1× phosphate buffer (imidazole concentrations of 20, 40, 60, 100, and 300 mM). The eluates were collected in 1-ml fractions, and the protein fractions were examined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Fractions containing purified protein were pooled to 2 to 3 ml and dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)-100 mM KCl-2 mM dithiothreitol-1 mM EDTA-10% glycerol. Purified proteins were flash frozen in aliquots and stored at −70°C. Protein concentrations were determined using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.).

Topoisomerase IV assay.

The reaction mixture (20 μl) for decatenation assays contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.7), 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 50 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml 250 mM potassium glutamate, 1 mM ATP, 100 ng of kinetoplast DNA (kDNA, from Crithidia fasciculata [TopoGEN, Inc., Columbus, Ohio]), and various amounts of GrlA and GrlB. Following incubation of the reaction mixtures at 37°C for 1 h, the reactions were terminated by addition of EDTA to a final concentration of 50 mM, and the products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide following electrophoresis.

DNA gyrase assay.

DNA supercoiling activity was assayed in buffer containing 75 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 7.5 mM MgCl2, 7.5 mM dithiothreitol, 2mM ATP, 75 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 30 mM KCl, 250 mM potassium glutamate, and 2 μg of tRNA with 0.5 μg of relaxed pBR322 as the substrate in a total volume of 20 μl. The reaction was carried out at 30°C for 1 h and stopped by addition of EDTA to a final concentration of 50 mM, and the products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose as for the topoisomerase IV assays.

RESULTS

Activities for genetically defined mutants.

As the initial step in determining the target specificity of garenoxacin, the susceptibilities of genetically defined mutants of S. aureus for garenoxacin were determined and compared with those for ciprofloxacin (Table 2). Ciprofloxacin MICs determined in this study were identical to or within one twofold dilution of those previously reported (24, 25). A gyrA mutation produced no more than a twofold change in the MIC of ciprofloxacin, but a mutation in either subunit of topoisomerase IV caused a four- to eightfold increase in the MIC of ciprofloxacin, patterns that are consistent with the its primary action targeting topoisomerase IV. Strains with mutations in both gyrA and topoisomerase IV genes were highly resistant to ciprofloxacin, with 64- to 128-fold increases in the MIC in comparison to the wild-type strain.

TABLE 2.

Activity of garenoxacin and ciprofloxacin against genetically defined mutants of S. aureus

| Strain | Mutation | MIC (μg/ml)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Garenoxacin | Ciprofloxacin | ||

| ISP794 | Wild type (parent) | 0.032 | 0.125-0.25 |

| MT5 | gyrB142 (Ile102Ser, Arg144Ile) | 0.032 | 0.125-0.25 |

| SS1 | gyrA (Ser84Leu) | 0.128 | 0.25 |

| MT5224c2 | grlA (Ala116Pro) | 0.064-0.128 | 1.0-2.0 |

| MT5224c3 | grlA (Ala116Glu) | 0.064-0.128 | 2.0 |

| MT111 | grlA (Ala116Glu) | 0.064-0.128 | 2.0 |

| MT5224c4 | grlA (Ser80Phe) | 0.128 | 1.0-2.0 |

| MT5224c9 | grlB (Asn470Asp) | 0.064-0.128 | 2.0 |

| P4 | grlA (Arg43Cys) | 0.064-0.128 | 1.0 |

| P21 | grlA (Asp69Tyr) | 0.064-0.128 | 1.0 |

| P10 | grlA (Ala176Thr) | 0.064-0.128 | 1.0 |

| GB | grlB (Pro25His) | 0.0128-0.256 | 1.0 |

| MT23142 | flqB (NorA overexpression) | 0.032-0.064 | 0.5-1.0 |

| EN1252a | grlA (Ser80Phe) gyrA (Ser84Leu) | 4.0 | 32 |

Garenoxacin was four- to eightfold more active than ciprofloxacin against wild-type S. aureus ISP794. The striking difference was in the response of the mutants to garenoxacin. Mutations in either gyrA or genes for either subunit of topoisomerase IV caused two- to fourfold increases in the MIC of garenoxacin, from 0.032 to 0.064 to 0.128 μg/ml. This finding suggested similar targeting of topoisomerase IV and gyrase by garenoxacin. Mutations in gyrA in combination with mutations in either grlA or grlB were needed for a substantial increase in resistance. Although this increment in the resistance of garenoxacin for double mutants was similar to that for ciprofloxacin (64- to 128-fold), garenoxacin remained 8- to 16-fold more active against these highly ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants (MIC, 4.0 μg/ml). Overexpression of the NorA efflux pump caused at most a twofold increase in the MIC of garenoxacin in comparison to a four- to eightfold increase in the MIC of ciprofloxacin.

Frequency of selection of mutants.

The frequencies of selection of single-step resistant mutants of wild-type strain ISP794 with garenoxacin and ciprofloxacin differed substantially (Table 3). Large numbers of bacteria had to be plated to be able to select for mutants using garenoxacin. Even at twice MIC, the selection frequency with garenoxacin was extremely low (<7.4 × 10−12 to 4.4 × 10−11), and there was at least a 5- to 6-log-unit difference between the selection frequencies of garenoxacin and ciprofloxacin at twice the MIC of each quinolone. Mutants could not be selected at fourfold the MIC of garenoxacin, whereas the frequency of selection at fourfold the MIC of ciprofloxacin was 3.0 × 10−8 to 6.1 × 10−8. Selection at the MIC of garenoxacin produced mutants at a frequency of 2.0 × 10−5 to 3.6 × 10−5, a 6-log-unit difference relative to selection at twice the MIC.

TABLE 3.

Frequency of selection of resistant mutants of strain ISP794

| Concn (μg/ml) of selecting drug | Factor of MIC of selecting drug

|

Frequency of selection of mutants

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garenoxacin | Ciprofloxacin | Garenoxacin | Ciprofloxacin | |

| 0.032 | 1 | ;@0017>2.0 × 10−5-3.6 × 10−5 | ||

| 0.064 | 2 | <7.4 × 10−12-4.0 × 10−11 | ||

| 0.128 | 4 | <7.4 × 10−12 | ||

| 0.5 | 2 | 2.8 × 10−6-1.5 × 10−5 | ||

| 1.0 | 4 | 3.0 × 10−8-6.1 × 10−8 | ||

| 2.0 | 8 | <4.5 × 10−11-2.8 × 10−9 | ||

Characterization of single-step mutants.

The MICs of garenoxacin and ciprofloxacin for four single-step mutants selected at twice the MIC of garenoxacin indicated two patterns (Table 4), an increase in the MIC of garenoxacin but not ciprofloxacin for two mutants (fourfold for mutant B2 and eightfold for B15) and an increase in the MIC of both garenoxacin and ciprofloxacin for two other mutants (eightfold and twofold, respectively, for mutant B23 and eightfold for both quinolones for mutant B26). Since this pattern of resistance in S. aureus was new, the entire sequences of grlA, grlB, gyrA, and gyrB were determined. In two of the mutants for which only the MICs of garenoxacin were increased, mutations in gyrA were found. One of these mutations was a conventional mutation in the QRDR, near the 5′ end of gyrA, encoding a Ser84Leu mutation; the other, however, was a novel mutation near the 3′ end of the gene, at codon 784, encoding Ser784Tyr. The MIC of nalidixic acid, which has been used as an indicator of gyrA mutations, was increased only for the strain with the conventional gyrA mutation. The MIC of ethidium bromide for mutant B2 with the novel gyrA mutation was not increased, and the sequence of the norA promoter region, mutations in which have been associated with resistance to quinolones by genetic studies (33), contained no mutation.

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of single-step mutants of S. aureus ISP794 selected with garenoxacin

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

Mutation(s) ind:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garenoxacin | CIP | NOV | NA | EB | grlA | grlB | gyrA | gyrB | norAb | |

| ISP794 | 0.032 | 0.125-0.25 | 0.064-0.128 | 64-128 | 2.0-4.0 | |||||

| B2 | 0.128 | 0.25 | 0.064 | 128 | 4.0 | None | None | Ser784Tyr | None | None |

| B15 | 0.256 | 0.25 | 0.064-0.128 | 256 | 2.0-4.0 | None | None | Ser84Leu | None | NDc |

| B23 | 0.256 | 0.25-0.5 | 0.064-0.128 | 128-256 | 2.0-4.0 | None | Asp33Tyr | Asn529Asn, Arg530His | None | ND |

| B26 | 0.256 | 2.0 | 0.064 | 128 | 4.0-8.0 | Thr292Ile | None | None | None | None |

CIP, ciprofloxacin; NOV, novobiocin; NA, nalidixic acid; EB, ethidium bromide.

Promoter region of norA.

ND, not done.

The indicated mutations in gyrA resulted from the following nucleotide changes: Ser784→Tyr, TCT→TAT; Ser84→Leu, TCA→ TTA; Asn529→Asn; AAC→AAT; Arg530His, CGT→CAT. The indicated mutations in grlB and grlA resulted from the following nucleotide changes, respectively: Asp33Tyr, GAT→TAT; Thr292→Ile, ACT→ATT.

Of the mutants for which the MICs of both quinolones were increased, mutant B23 had an interesting pattern in which the MIC of garenoxacin had increased, relatively more than that of ciprofloxacin (eight- and twofold, respectively). The MIC of nalidixic acid was also twofold higher for this strain. Interestingly, sequencing of all four genes for this strain showed two novel mutations outside the QRDRs, a mutation in grlB, encoding Asp33Tyr and a mutation in gyrA encoding Arg530His, together with a silent mutation at codon 529 of gyrA (Asn529, AAC→ AAT). The relatively higher increase in resistance to garenoxacin in comparison to ciprofloxacin suggested that these novel mutations had different effects on resistance to different quinolones; however, at this step, we could not determine if both mutations contributed to resistance to both quinolones. The only mutation found in the last mutant studied, B26 (eightfold increase in MICs of both quinolones) was a conservative mutation in grlA outside the QRDR, encoding Thr292Ile. The MIC of novobiocin, hypersusceptibility to which has been associated with selected grlA or grlB mutations, was not changed for these two mutants. Although the MIC of ethidium bromide was increased twofold for mutant B26, no mutation in the promoter region of norA was found.

Selection and characterization of serial-passage mutants.

Mutants selected by serial passage on garenoxacin and their characteristics are shown in Table 5. The MICs of garenoxacin and ciprofloxacin for the first-step mutant selected at twice the MIC of garenoxacin (0.064 μg/ml) were increased only twofold, and there was no change in the MICs of nalidixic acid, novobiocin, or ethidium bromide. For the second-step mutant (BS2), which was selected at 0.125 μg/ml, a higher increase in the MIC of garenoxacin was observed. The MIC of ciprofloxacin increased 4- to 8-fold (up to 1.0 μg/ml), and the MIC of garenoxacin increased 16-fold (up to 0.5 μg/ml). Also, the MIC of nalidixic acid increased fourfold. DNA sequencing of all of grlA and grlB did not reveal any mutation. When all of gyrA and gyrB were sequenced, only a novel mutation was found at codon 486 of gyrB, encoding Gly486Val, a mutation not present in the first-step mutant. Since there were no mutations in topoisomerase IV or gyrA in the second-step mutant and any mutation in the first-step mutant should be carried on to the second-step mutant, complete sequencing of these genes in the first-step mutant was not performed. Since the MIC of garenoxacin for the second-step mutant (BS2) had increased more than fourfold, it grew readily on the next selecting concentration of garenoxacin, 0.25 μg/ml. Therefore, mutants BS2 and BS3 appear to be the same. Further selection occurred at step 3 at 0.5 μg/ml, producing a mutant (BS4-5) for which there was a fourfold increase in the MIC of garenoxacin to 2.0 μg/ml but no change in the MIC of ciprofloxacin. Absence of an increase in the MIC of ciprofloxacin for this third-step mutant suggested a mutation in DNA gyrase, and sequencing of the entire gyrA and gyrB genes revealed a commonly encountered mutation in the QRDR of gyrA, encoding Ser84Leu. The QRDRs of both grlA and grlB were also sequenced, and no mutation was found. The fourth-step selection at a garenoxacin concentration of 2 μg/ml produced a mutant (BS6) for which there was 500-fold increase in the MIC of garenoxacin (up to 16 μg/ml) and a 125- to 250-fold increase in the MIC of ciprofloxacin (up to 32 μg/ml). The MIC of novobiocin for this mutant did not change. Sequencing of the QRDRs of all four genes revealed a conventional mutation in only grlA, encoding Ser80Phe, in addition to the mutations identified in earlier steps. More resistant mutants could not be selected on higher concentrations of garenoxacin. Thus, high-level resistance to garenoxacin was reached after four steps of selection. Mutants with ethidium bromide resistance, indicating overexpression of the NorA efflux pump, were not selected in any of the steps.

TABLE 5.

Characteristics of serial-passage mutants of S. aureus ISP794 selected with garenoxacin

| Strain (selecting concn, μg/ml) | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

Mutation(s) inc:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garenoxacin | CIP | NOV | NA | EB | grlA | grlB | gyrA | gyrB | |

| ISP794 | 0.032 | 0.125-0.25 | 0.064-0.128 | 64-128 | 2.0-4.0 | ||||

| BS1 (0.064) | 0.064 | 0.25-0.5 | 0.128 | 64 | 4.0 | Noneb | Noneb | Noneb | None |

| BS2 (0.125) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.128 | 256 | 4.0 | ||||

| BS3 (0.25) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.128 | 256 | 4.0 | None | None | None | Gly486Val |

| BS4 (0.5) | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.064 | 256 | 2.0 | Noneb | Noneb | Ser84Leu | Gly486Val |

| BS5 (1.0) | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.064 | 256 | 2.0 | ||||

| BS6 (2.0) | 16 | 32 | 0.064 | 256 | 2.0 | Ser80Pheb | Noneb | Ser84Leu | Gly486Val |

CIP, ciprofloxacin; NOV, novobiocin; NA, nalidixic acid; EB, ethidium bromide.

QRDR.

The indicated mutations resulted from the following nucleotide changes: Gly486→Val in gyrB, GGT→GTT; Ser84→Leu in gyrA, TCA→TTA; Ser80→Phe in grlA, TCC→TTC.

Confirmation of the role of novel mutations in resistance by allelic exchange.

Allelic exchange experiments were performed for all five novel mutations. Since the MIC of garenoxacin for the genetically defined mutant SS1 with the Ser84Leu GyrA mutation had previously been determined and the result was similar (twofold difference) to that for the single-step mutant B15 with the same mutation, an allelic exchange experiment was not performed with B15. For allelic exchange experiments, after growing the cells at permissive temperature for excision of the plasmid pCL52.2, cells were screened for susceptibility to tetracycline and resistance to garenoxacin. For mutant B2, only 2 of 1,000 colonies were tetracycline susceptible and garenoxacin resistant. The MICs of garenoxacin (0.128 μg/ml) and ciprofloxacin (0.25μg/ml) for the original and the allelic exchange mutants (B2 and DIB2) were identical. DNA sequencing confirmed the presence of gyrA (Ser784Tyr) in DIB2. We were unable to identify any quinolone-resistant colonies following three separate grlA and gyrB allelic exchange experiments with mutants B26 and BS3, respectively, including screening of at least 1,000 candidate allelic exchange transformants in each experiment.

The gyrA (Arg530His) and grlB (Asp33Tyr) mutations from strain B23 were introduced independently into the chromosome of wild-type ISP794. No gyrA transformant could be identified on screening for garenoxacin resistance, but, in contrast, the grlB mutation (Asp33Tyr) could be introduced independently of the gyrA mutation, and the MICs of ciprofloxacin and garenoxacin for the resultant allelic exchange transformant (DIB23B) both increased twofold, for ciprofloxacin reaching the MIC of ciprofloxacin for the original mutant (0.5 μg/ml). The MIC of garenoxacin for the transformant DIB23B (0.064 μg/ml) was, however, fourfold lower than the MIC for the original mutant, B23, with the double mutation (0.256 μg/ml). This finding suggested that the novel mutation in gyrA, in the presence of the grlB mutation, should be contributing to resistance to garenoxacin but not to ciprofloxacin. To investigate this hypothesis, the novel mutation in gyrA (encoding Arg530His) from strain B23 was introduced into transformant DIB23B by allelic exchange, yielding transformant DIB23BA. The MIC of garenoxacin increased another fourfold following the introduction of the gyrA mutation (up to 0.256 μg/ml), increasing to same value as for the original mutant, B23. Interestingly, this novel gyrA mutation did not cause an increase in the MIC of ciprofloxacin in the presence of the grlB mutation. Thus, the individual contributions of the two mutations to the resistance phenotype seen in the double mutant were able to be reconstructed.

We also introduced the novel grlB mutation into strain SS1 (gyrA Ser84Leu). For the resultant transformants with double mutations [grlB (Asp33Tyr) gyrA (Ser84Leu)], the MIC of garenoxacin increased fourfold (up to 0.5 μg/ml) and the MIC of ciprofloxacin increased twofold (up to 0.5 μg/ml) in comparison to their MICs for SS1. In contrast, the MICs of both quinolones for a double mutant with conventional mutations in grlA and gyrA (EN1252a) were substantially higher (Table 2). Thus, grlB (Asp33Tyr) contributes additively less of an increment in resistance to gyrA (Ser84Leu) than does grlA (Ser80Phe).

Comparative activity of garenoxacin and ciprofloxacin against purified topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase.

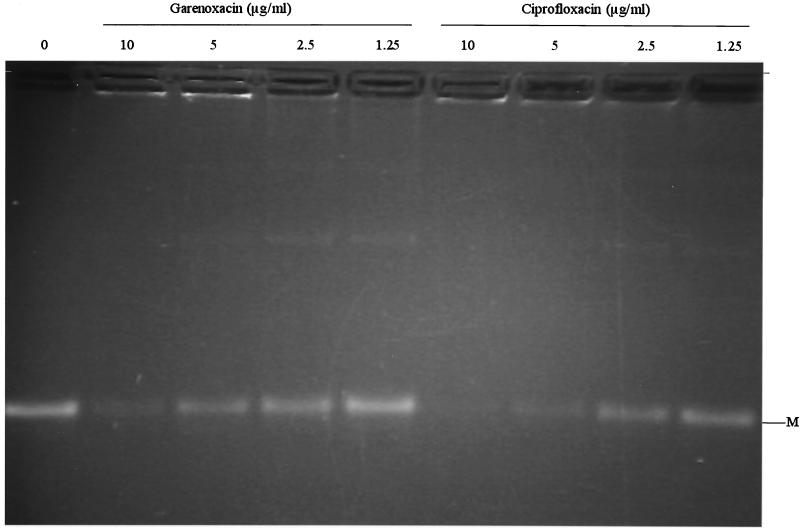

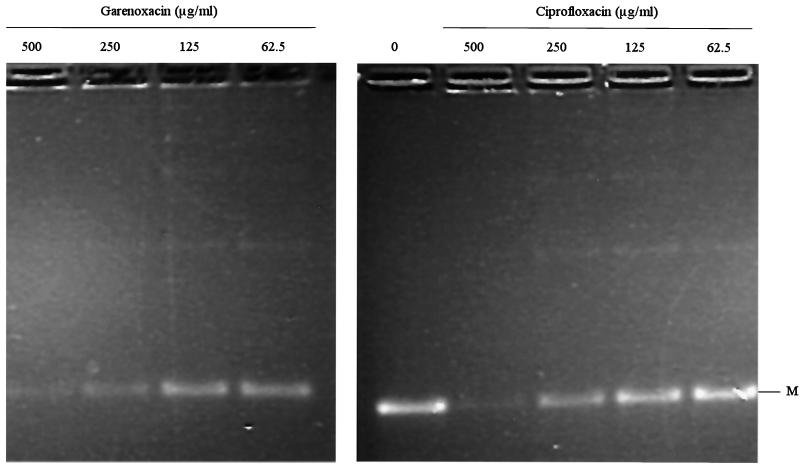

The subunits of topoisomerase IV were purified separately as histidine-tagged proteins. Individual subunits appeared >90% homogeneous by SDS-PAGE (data not shown). Specific activities of individual subunits of topoisomerase IV were determined in the presence of an excess of the complementing wild-type subunit. One unit was defined to be the amount of enzyme that produces half-maximal decatenation of 0.2 μg of kDNA. Specific activities of the GrlA and GrlB proteins of ISP794 used in the decatenation assays were determined to be 1.8 × 105 and 5.3 × 105 U/mg, respectively, and the specific activity of the GrlA protein from mutant MT5224c4 (Ser80Phe) was 3.6 × 105 U/mg. GrlA and GrlB subunits just sufficient to fully decatenate the kDNA minicircles (usually 2 U) were used for decatenation assays, and reactions were carried out in the presence and absence of increasing concentrations of garenoxacin or ciprofloxacin to determine 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50), defined as the concentration of drug that reduces the intensity of the kDNA minicircle band by half. Both quinolones resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of decatenation. The IC50s of garenoxacin and ciprofloxacin for the wild-type topoisomerase IV were similar (1.25 to 2.5 and 2.5 to 5.0 μg/ml, respectively) (Fig. 1), and both increased similarly, about 100-fold for the grlA mutant (125 to 250 μg/ml for garenoxacin and 250 μg/ml for ciprofloxacin) (Fig. 2; Table 6).

FIG. 1.

Decatenation of kDNA by wild-type GrlA and GrlB in the presence of garenoxacin and ciprofloxacin. Assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. M, minicircles.

FIG. 2.

Decatenation of kDNA by GrlA (Ser80Phe) and wild-type GrlB in the presence of garenoxacin and ciprofloxacin. M, minicircles.

TABLE 6.

Inhibitory effects of garenoxacin and ciprofloxacin on wild-type and mutant (grlA) topoisomerase IV and wild-type gyrase

| Enzyme | Subunits

|

IC50

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GrlA | GrlB | GyrA | GyrB | Garenoxacin | Ciprofloxacin | |

| Topoisomerase IV | Wild type | Wild type | 1.25-2.5 | 2.5-5.0 | ||

| Topoisomerase IV | Phe80 | Wild type | 125-250 | 250 | ||

| Gyrase | Wild type | Wild type | 1.25 | 10 | ||

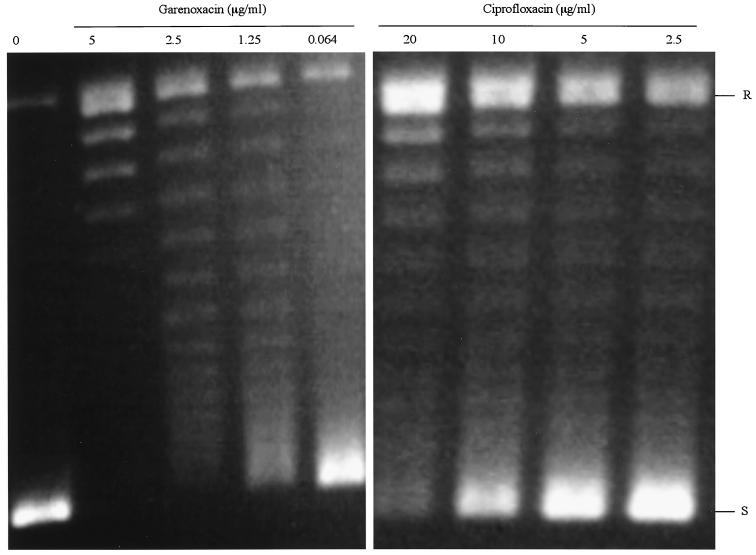

The GyrA and GyrB subunits were purified similarly to histidine-tagged proteins and exhibited >90% homogeneity by SDS-PAGE (data not shown). Specific activities were also determined for GyrA and GyrB proteins from the wild-type S. aureus ISP794. For DNA gyrase, 1 U was defined as the amount of enzyme that produces half-maximal supercoiling of 0.5 μg of relaxed pBR322 DNA, and the specific activities of GyrA and GyrB were determined as 1.1 × 104 and 5.2 × 103 U/mg, respectively. The IC50 for DNA gyrase supercoiling activity was determined in the presence of amounts of GyrA and GyrB just sufficient to fully supercoil the relaxed substrate DNA (often 2 u) and was defined as the concentration of drug that reduces the intensity of the most supercoiled DNA band by half. DNA supercoiling was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner, and the IC50 of garenoxacin for wild-type gyrase (1.25 μg/ml) was the same or twofold lower than its IC50 for topoisomerase IV and about eightfold lower than the IC50 of ciprofloxacin for wild-type gyrase (10 μg/ml) (Fig. 3; Table 6). The conditions for the decatenation and supercoiling assays were optimized to obtain maximum activity of each enzyme. The most striking difference between garenoxacin and ciprofloxacin was the >10-fold increase in the potency of garenoxacin against S. aureus DNA gyrase.

FIG. 3.

DNA-supercoiling activity of gyrase in the presence of of garenoxacin and ciprofloxacin. R and S, relaxed and supercoiled DNA, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Garenoxacin has been reported to be 4- to 16-fold more active than ciprofloxacin against clinical isolates of methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (15, 16, 44, 50). We found garenoxacin to be four- to eightfold more active than ciprofloxacin against a genetically defined strain of S. aureus. Classically, MICs of quinolones increase for mutants with a mutation in the more sensitive (primary) target of the quinolone, and mutations in the less sensitive (secondary) target are silent unless in the presence of resistance mutations in the primary target. For resistance mutations in the primary target, the increment in resistance may be determined by the level of sensitivity of the second (or less sensitive) target. Thus, the level of resistance due to mutation in the primary target should decrease as the level of sensitivity of the second target approaches that of the primary target. If a quinolone has equal potencies against both targets, mutations in both target enzymes should be necessary for resistance (23). It has been well established that ciprofloxacin has topoisomerase IV as the primary target in S. aureus (11, 34, 52). The similar two- to fourfold increases in the MICs of garenoxacin for genetically defined gyrA or topoisomerase IV mutants suggested that garenoxacin targets both enzymes similarly. Other nonfluorinated quinolones have also been reported to target both enzymes more evenly than ciprofloxacin, as evident from MIC studies performed with some of the same genetically defined mutants used in this study (39). MICs of garenoxacin for first-step topoisomerase IV or gyrase mutants (0.064 to 0.128 μg/ml) are substantially below the drug concentrations achievable in serum after single doses of 400 and 800 mg (6.4 and 10.9 μg/ml, respectively) (18). These findings suggest that the frequency of selection of resistant mutants from wild-type strains of S. aureus would be unlikely with the use of garenoxacin in clinical settings (22).

Garenoxacin, which has been reported to be little affected by the PmrA efflux pump in S. pneumoniae (4), also seems to be a poor substrate for the homologous NorA efflux pump in S. aureus; overexpression of the NorA efflux pump had minimal effect on the MIC of garenoxacin, and no mutants with ethidium bromide resistance or mutations in the promoter region of norA were selected with either single-step or serial-step selection. Recent data indicate that sparfloxacin, a fluoroquinolone whose activity is not affected by NorA overexpression, interacts with NorA differently from ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin, which are substrates of this efflux pump (54). Kinetic competition experiments of NorA transport of the dye Hoechst 33342 indicate that sparfloxacin binds NorA at a site different from that to which ciprofloxacin or norfloxacin binds, suggesting the possibility that garenoxacin might also interact with NorA in a way that is nonproductive for transport.

Since susceptibilities of existing genetically defined mutants suggested that garenoxacin targeted both enzymes similarly but could not clearly differentiate a preferred target, we selected single- and serial-step mutants with garenoxacin. First, selection of mutants proved to be difficult above the MIC. At twice the MIC of garenoxacin for ISP794, the highest concentration at which mutants could be selected, the selection frequency of resistant mutants was extremely low. Such extremely low frequencies of selection of mutants have previously been reported for clinafloxacin, which targets both gyrase and topoisomerase IV in S. pneumoniae (37), and for other nonfluorinated quinolones in S. aureus (39). Second, the characterization of single-step mutants yielded interesting results in that two of the mutants had gyrA mutations, one had a grlA mutation, and one (B23) had mutations in both grlB and gyrA. These findings also suggested that gyrase and topoisomerase IV were similarly targeted by garenoxacin in vivo. The finding of dual mutations with single-step selections, as has also been previously reported with premafloxacin (24) and moxifloxacin (27), however, emphasizes the need for genetic exhange experiments to link genotype and phenotype definitively.

We thus performed allelic exchange experiments for the grlB (Asp33Tyr) and gyrA (Arg530His) mutations in the B23 double mutant independently to determine their roles in resistance. Despite repeated attempts with mutant gyrA (Arg530His), no transformants resistant to garenoxacin could be identified. The grlB mutation, however, was itself sufficient to cause low-level but reproducible resistance to garenoxacin, suggesting that topoisomerase IV behaved as the primary target for this mutation. The introduction of the second mutation in gyrA reproduced the phenotype of the original dual mutant.

Allelic exchange experiments provided evidence that garenoxacin targets gyrase as well. The increase in the MIC of garenoxacin following introduction of the Ser784Tyr mutation in gyrA from one of the single-step mutants (B2) into the wild-type S. aureus chromosome showed that a mutation in gyrase selected by garenoxacin was responsible alone for the resistance phenotype. Furthermore, the selection of a conventional Ser84Leu mutation in gyrA in another single-step mutant and the increase in the MIC of garenoxacin for our previously constructed mutant of ISP794 (SS1) with the gyrA (Ser84Leu) mutation provided additional genetic data for primary targeting of gyrase by garenoxacin in intact cells. Thus, genetic experiments provide evidence of targeting of both topoisomerase IV and gyrase by garenoxacin. Although there is evidence of dual targeting, there appears to be a slight preference for gyrase, since the magnitude of the effect on resistance of the gyrA mutations selected was greater than that of the grlB mutation selected, and the only grlA mutation singly selected with garenoxacin could not be confirmed. Others have also suggested a preference of garenoxacin for gyrase as a primary target (6).

We have for the first time demonstrated the similarity of the activity of garenoxacin against both wild-type target enzymes in S. aureus in vitro, although gyrase was slightly more sensitive than topoisomerase IV, perhaps accounting for an apparent slight preference for gyrase as a primary target in vivo. Although assay conditions optimized for activity in vitro may not necessarily reflect conditions in vivo, in this case the biochemical results are concordant with the genetic results for both ciprofloxacin and garenoxacin. Interestingly, purified topoisomerase IV reconstituted with the mutant GrlA subunit (Phe80) produced a 100-fold increase in resistance to garenoxacin relative to the wild-type topoisomerase IV. In contrast, the strain with same mutation exhibited only a fourfold increase in the MIC of garenoxacin, further supporting the concept that the level of resistance in vivo is limited by the level of drug sensitivity of the second-target enzyme (51). Because quinolones act by stabilization of cleavable complexes which are thought to be the cytotoxic lesions leading to their antibacterial action, future comparison of the formation of enzyme DNA cleavage complexes by garenoxacin and ciprofloxacin may be informative in correlating activities in vitro and in vivo (30).

Previous reports of MIC results, frequency of selection of resistant mutants, cell growth inhibition, or introduction of mutations in grlAB on a plasmid into wild-type or mutant S. aureus have suggested that sparfloxacin (12, 52), sitafloxacin (DU6859a) (12), pazufloxacin, moxifloxacin, clinafloxacin (45), and some nonfluorinated quinolones (39, 40) target topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase similarly in S. aureus. The combination of our genetic data on selection of both topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase mutations in first-step mutants and biochemical data on similar inhibition of both enzymes in vitro indicates the dual targeting of gyrase and topoisomerase IV in S. aureus by garenoxacin as well.

Selections using quinolones with increasing potency against S. aureus have generated a striking diversity of mutants. We have previously reported that gatifloxacin and premafloxacin select for novel mutations outside the QRDR of S. aureus, necessitating the expansion of the QRDR in grlA to include codons 23 to 176 and in grlB to include codon 25 in addition to the midportions of the gene (24, 25). Moxifloxacin also selects for a novel mutation (His103Tyr) outside the QRDR of parE in S. pneumoniae (27), and a mutation in codon 51 of gyrA in E. coli has been reported to be responsible for resistance to quinolones (13).

In this study, we have selected five novel mutations, all outside the classical QRDRs of either subunit of topoisomerase IV or DNA gyrase. The mutation in GrlB (Asp33Tyr) is distant from the midportion of the protein, where previously identified mutations are clustered, and is in the domain involved in ATPase activity (5). Amino acid residues 2 to 15 of GyrB in E. coli extend from the ATPase domain surface to form dimer contacts with the other monomers that are required for ATP hydrolysis (48, 49). We have also previously reported a quinolone resistance mutation in codon 25 in grlB (Pro25His) selected with gatifloxacin in S. aureus, which causes a fourfold increase in the MICs of ciprofloxacin and gatifloxacin (25). Whether these two mutations impair the dimerization of the ATPase domains required for ATP hydrolysis or cause resistance by another mechanism is unknown.

Other novel mutations in GyrA, Ser784Tyr and Arg530His, which contribute to resistance to garenoxacin, are located in the carboxy-terminal region. The C terminus of E. coli gyrase A and yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and Drosophila DNA topoisomerase II are known to be dispensible for the catalysis of DNA transport (5, 48). Also, the similarity of the C-terminal domains of type II enzymes in closely related species is localized to the amino-proximal half of this domain (5). The C-terminal fragment of E. coli GyrA is involved in the right-handed wrapping of DNA around the enzyme, necessary for negative supercoiling (5, 48). In S. cerevisiae topoisomerase II, the C-terminal domain is involved in nuclear targeting and interactions with other proteins (5). Amino acid residues near the C terminus have been suggested to play an important role in drug-enzyme interactions (8) and formation of stable ternary complexes to arrest replication fork progression (20). The mechanism by which the Ser784Tyr and Arg530His garenoxacin-selected mutations cause resistance is as yet unknown but might possibly be related to alterations in the formation of ternary complexes of drug, enzyme, and DNA.

For the other two novel mutations (Thr292Ile in GrlA and Gly486Val in GyrB), no resistant transformants could be identified following allelic exchange despite extensive efforts. Thus, the role of GrlA (Thr292Ile) and GyrB (Gly486Val) in resistance to garenoxacin remains unclear. The novel mutation at position 292 of GrlA is located in the β12 sheet of the enzyme, and the amino acid at position 292 is not conserved in either E. coli gyrase or yeast topoisomerase II. The mutation at position 486 in GyrB, which is located in the α3 helix of gyrase B (corresponding to the conserved glycine 503 of yeast topoisomerase II), is close to the highly conserved PLRGKMLNV region of yeast topoisomerase II between residues 473 and 481 (12). Structures of various enzyme conformations suggest that this highly conserved region might come in proximity to the classical gyrase A QRDR to form a putative quinolone binding pocket (9). Quinolone resistance mutations at positions 426 and 447 in E. coli GyrB (53) and positions 437 and 458 in S. aureus GyrB are associated with resistance (26). Roychoudhury et al. have selected another novel mutation in gyrB in codon 477 (Glu477Val), in addition to other novel mutations, with PGE 9509924, another nonfluorinated quinolone (39). The role of the these mutations in the resistance phenotype, however, has not yet been shown definitively by allelic exchange (39). Because quinolones cause DNA damage in bacteria and because DNA repair responses can be error prone (1), additional mutations not contributing to the resistance phenotype can occur with quinolone exposure and selection, indicating the importance of genetic studies of novel mutations to confirm their role in resistance.

In summary, garenoxacin interacts similarly with both DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV and has generated novel mutations expanding the range of the QRDR to both the amino-terminal domain of GrlB and the carboxy-terminal domain of GyrA. This novel desfluoroquinolone, with its high potency and low frequency of selection of resistant mutants, may thus prove advantageous in clinical settings, decreasing the possibility of selection of new resistant mutants. Strains with previously selected multiple quinolone resistance mutations, as is now common with methicillin-resistant clinical isolates of S. aureus, however, exhibit cross-resistance to garenoxacin that may limit the utility of this antibiotic for treatment of strains with established resistance to earlier quinolones.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Y. Lee for plasmid pCL52.2.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the U.S. Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health (R01 AI23988 to D.C.H.), and a grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb Co (to D.C.H.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Baguley, B. C., and L. R. Ferguson. 1998. Mutagenic properties of topoisomerase-targeted drugs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Struct. Expression 1400:213-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball, P. 2000. Quinolone generations: natural history or natural selection? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisognano, C., P. E. Vaudaux, D. P. Lew, E. Y. W. Ng, and D. C. Hooper. 1997. Increased expression of fibronectin-binding proteins by fluoroquinolone-resistant Staphylococcus aureus exposed to subinhibitory levels of ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:906-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boswell, F. J., J. M. Andrews, and R. Wise. 2001. Comparison of the in vitro activities of BMS-284756 and four fluoroquinolones against Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:446-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Champoux, J. J. 2001. DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:369-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Discotto, L. F., L. E. Lawrence, K. L. Denbleyker, and J. F. Barrett. 2001. Staphylococcus aureus mutants selected by BMS-284756. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3273-3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Domagala, J. M. 1994. Structure-activity and structure-side-effect relationships for the quinolone antibacterials. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 33:685-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elsea, S. H., Y. Hsiung, J. L. Nitiss, and N. Osheroff. 1995. A yeast type II topoisomerase selected for resistance to quinolones. Mutation of histidine 1012 to tyrosine confers resistance to nonintercalative drugs but hypersensitivity to ellipticine. J. Biol. Chem. 270:1913-1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fass, D., C. E. Bogden, and J. M. Berger. 1999. Quaternary changes in topoisomerase II may direct orthogonal movement of two DNA strands. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:322-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrero, L., B. Cameron, and J. Crouzet. 1995. Analysis of gyrA and grlA mutations in stepwise-selected ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1554-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrero, L., B. Cameron, B. Manse, D. Lagneaux, J. Crouzet, A. Famechon, and F. Blanche. 1994. Cloning and primary structure of Staphylococcus aureus DNA topoisomerase IV: a primary target of fluoroquinolones. Mol. Microbiol. 13:641-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fournier, B., and D. C. Hooper. 1998. Mutations in topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase of Staphylococcus aureus: novel pleiotropic effects on quinolone and coumarin activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:121-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman, S. M., T. Lu, and K. Drlica. 2001. Mutation in the DNA gyrase A gene of Escherichia coli that expands the quinolone resistance-determining region. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2378-2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukuda, H., and K. Hiramatsu. 1999. Primary targets of fluoroquinolones in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:410-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fung-Tomc, J., L. Valera, B. Minassian, D. Bonner, and E. Gradelski. 2001. Activity of the novel des-fluoro(6) quinolone BMS-284756 against methicillin-susceptible and -resistant staphylococci. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:735-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fung-Tomc, J. C., B. Minassian, B. Kolek, E. Huczko, L. Aleksunes, T. Stickle, T. Washo, E. Gradelski, L. Valera, and D. P. Bonner. 2000. Antibacterial spectrum of a novel des-fluoro(6) quinolone, BMS-284756. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3351-3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hane, M. W., and T. H. Wood. 1969. Escherichia coli K-12 mutants resistant to nalidixic acid: genetic mapping and dominance studies. J. Bacteriol. 99:238-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartman-Neumann, S., K. Denbleyker, L. A. Pelosi, L. E. Lawrence, J. F. Barrett, and T. J. Dougherty. 2001. Selection and genetic characterization of Streptococcus pneumoniae mutants resistant to the des-F(6) quinolone BMS-284756. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2865-2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heaton, V. J., J. E. Ambler, and L. M. Fisher. 2000. Potent antipneumococcal activity of gemifloxacin is associated with dual targeting of gyrase and topoisomerase IV, an in vivo target preference for gyrase, and enhanced stabilization of cleavable complexes in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3112-3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiasa, H., and M. E. Shea. 2000. DNA gyrase-mediated wrapping of the DNA strand is required for the replication fork arrest by the DNA gyrase-quinolone-DNA ternary complex. J. Biol. Chem. 275:34780-34786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hooper, D. C. 1999. Mechanisms of quinolone resistance. Drug Resist. Updates 2:38-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hooper, D. C. 2000. Mechanisms of action and resistance of older and newer fluoroquinolones. Clin. Infect. Dis. 31:S24-S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hooper, D. C. 2001. Mechanisms of action of antimicrobials: focus on fluoroquinolones. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:S9-S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ince, D., and D. C. Hooper. 2000. Mechanisms and frequency of resistance to premafloxacin in Staphylococcus aureus: novel mutations suggest novel drug-target interactions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3344-3350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ince, D., and D. C. Hooper. 2001. Mechanisms and frequency of resistance to gatifloxacin in comparison to AM-1121 and ciprofloxacin in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2755-2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito, H., H. Yoshida, M. Bogaki-Shonai, T. Niga, H. Hattori, and S. Nakamura. 1994. Quinolone resistance mutations in the DNA gyrase gyrA and gyrB genes of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:2014-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janoir, C., E. Varon, M. D. Kitzis, and L. Gutmann. 2001. New mutation in ParE in a pneumococcal in vitro mutant resistant to fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:952-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones, R. N., M. A. Pfaller, and M. Stilwell. 2001. Activity and spectrum of BMS 284756, a new des-F(6) quinolone, tested against strains of ciprofloxacin-resistant Gram-positive cocci. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 39:133-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaatz, G. W., and S. M. Seo. 1995. Inducible NorA-mediated multidrug resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2650-2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khodursky, A. B., and N. R. Cozzarelli. 1998. The mechanism of inhibition of topoisomerase IV by quinolone antibacterials. J. Biol. Chem. 273:27668-27677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawrence, L. E., P. Wu, L. Fan, K. E. Gouveia, A. Card, M. Casperson, K. Denbleyker, and J. F. Barrett. 2001. The inhibition and selectivity of bacterial topoisomerases by BMS-284756 and its analogues. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:195-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu, T., X. L. Zhao, and K. Drlica. 1999. Gatifloxacin activity against quinolone-resistant gyrase: allele-specific enhancement of bacteriostatic and bactericidal activities by the C-8-methoxy group. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2969-2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ng, E. Y., M. Trucksis, and D. C. Hooper. 1994. Quinolone resistance mediated by norA: physiologic characterization and relationship to flqB, a quinolone resistance locus on the Staphylococcus aureus chromosome. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1345-1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng, E. Y., M. Trucksis, and D. C. Hooper. 1996. Quinolone resistance mutations in topoisomerase IV: relationship of the flqA locus and genetic evidence that topoisomerase IV is the primary target and DNA gyrase the secondary target of fluoroquinolones in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1881-1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Novick, R. P. 1991. Genetic systems in staphylococci. Methods Enzymol. 204:587-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan, X. S., and L. M. Fisher. 1997. Targeting of DNA gyrase in Streptococcus pneumoniae by sparfloxacin: selective targeting of gyrase or topoisomerase IV by quinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:471-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan, X. S., and L. M. Fisher. 1998. DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV are dual targets of clinafloxacin action in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2810-2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan, X. S. and L. M. Fisher. 1999. Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV: overexpression, purification, and differential inhibition by fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1129-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roychoudhury, S., C. E. Catrenich, E. J. McIntosh, H. D. McKeever, K. M. Makin, P. M. Koenigs, and B. Ledoussal. 2001. Quinolone resistance in staphylococci: activities of new nonfluorinated quinolones against molecular targets in whole cells and clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1115-1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roychoudhury, S., T. L. Twinem, K. M. Makin, M. A. Nienaber, C. Y. Li, T. W. Morris, B. Ledoussal, and C. E. Catrenich. 2001. Staphylococcus aureus mutants isolated via exposure to nonfluorinated quinolones: detection of known and unique mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3422-3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanders, C. C. 2001. Mechanisms responsible for cross-resistance and dichotomous resistance among the quinolones. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:S1-S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sau, S., J. W. Sun, and C. Y. Lee. 1997. Molecular characterization and transcriptional analysis of type 8 capsule genes in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 179:1614-1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stahl, M. L., and P. A. Pattee. 1983. Confirmation of protoplast fusion-derived linkages in Staphylococcus aureus by transformation with protoplast DNA. J. Bacteriol. 154:406-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takahata, M., J. Mitsuyama, Y. Yamashiro, M. Yonezawa, H. Araki, Y. Todo, S. Minami, Y. Watanabe, and H. Narita. 1999. In vitro and in vivo antimicrobial activities of T-3811ME, a novel des-F(6)-quinolone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1077-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takei, M., H. Fukuda, R. Kishii, and M. Hosaka. 2001. Target preference of 15 quinolones against Staphylococcus aureus, based on antibacterial activities and target inhibition. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3544-3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trucksis, M., J. S. Wolfson, and D. C. Hooper. 1991. A novel locus conferring fluoroquinolone resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 173:5854-5860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Varon, E., C. Janoir, M. D. Kitzis, and L. Gutmann. 1999. ParC and GyrA may be interchangeable initial targets of some fluoroquinolones in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:302-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, J. C. 1998. Moving one DNA double helix through another by a type II DNA topoisomerase: the story of a simple molecular machine. Q. Rev. Biophys. 31:107-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wigley, D. B., G. J. Davies, E. J. Dodson, A. Maxwell, and G. Dodson. 1991. Crystal structure of an N-terminal fragment of the DNA gyrase B protein. Nature 351:624-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu, P., L. E. Lawrence, K. L. Denbleyker, and J. F. Barrett. 2001. Mechanism of action of the des-F(6) quinolone BMS-284756 measured by supercoiling inhibition and cleavable complex assays. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3660-3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yague, G., J. E. Morris, X. S. Pan, K. A. Gould, and L. M. Fisher. 2002. Cleavable-complex formation by wild-type and quinolone-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae type II topoisomerases mediated by gemifloxacin and other fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:413-419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamagishi, J. I., T. Kojima, Y. Oyamada, K. Fujimoto, H. Hattori, S. Nakamura, and M. Inoue. 1996. Alterations in the DNA topoisomerase IV grlA gene responsible for quinolone resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1157-1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshida, H., M. Bogaki, M. Nakamura, L. M. Yamanaka, and S. Nakamura. 1991. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrB gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1647-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu, J.-L., L. L. Grinius, and D. C. Hooper. 2002. NorA functions as a multidrug transporter in everted membrane vesicles and proteoliposomes. J. Bacteriol. 184:1370-1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao, B. Y., R. Pine, J. Domagala, and K. Drlica. 1999. Fluoroquinolone action against clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: effects of a C-8 methoxyl group on survival in liquid media and in human macrophages. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:661-666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao, X. L., J. Y. Wang, C. Xu, Y. Z. Dong, J. F. Zhou, J. Domagala, and K. Drlica. 1998. Killing of Staphylococcus aureus by C-8-methoxy fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:956-958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]