Abstract

CD8+ T-cell persistence can be seen in ganglia harboring latent herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. While there is some evidence that these cells suppress virus reactivation, this view remains controversial. Given that maintenance of latency by CD8+ T cells would necessitate ongoing exposure to antigen within this site, we sought evidence for such chronic stimulation. Initial experiments showed infiltration by activated but not naïve CD8+ T cells into ganglia harboring latent HSV infection. While such infiltration was independent of T-cell specificity, once recruited, only virus-specific T cells expressed high levels of preformed granzyme B, a marker of ongoing activation. Moreover, bone marrow replacement chimeras showed that these elevated granzyme levels were totally dependent on presentation by parenchymal cells within the ganglia. Overall, this study argues that activated CD8+ T cells are nonspecifically recruited into latently infected ganglia, and in this site they are exposed to ongoing antigen stimulation, most likely by infected neuronal cells.

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) latency was originally thought to be a “silent” infection during which all virus gene expression was shut down, with the exception of the latency-associated transcripts (LATs). It was thought that this silence led to a state that was largely invisible to the immune system. Evidence supporting LAT expression in the absence of lytic gene and protein expression was originally provided by both human (5, 14, 21) and animal studies (15, 51, 52) of latently infected ganglia. However, with the evolution of more sensitive detection methods, the transcription of several lytic genes has now been demonstrated in latently infected ganglia (22, 32), with evidence from murine studies suggesting some level of lytic protein expression in a small proportion of latently infected neurons (18).

Together with the demonstration of lytic gene expression during latency comes evidence of a persisting immune response within latently infected ganglia. Studies in humans, mice, and rabbits have shown the persistence of inflammatory cells and cytokines long after the clearance of infectious virus (12, 23, 35, 48, 54), although some have reported the eventual clearance of the immune infiltrate with time (10, 19). The presence of cytokines such as gamma interferon and the finding that persisting lymphocytes localize to neurons within the ganglia (29) has resulted in the proposal that continual or intermittent HSV-1 antigen expression is occurring during latency (10).

While the presence of activated CD8+ T cells within latently infected ganglia has been used to argue that these cells are involved in maintaining viral latency (29, 30), the mechanisms through which they remain activated has not been fully elucidated. Furthermore, little is known as to what influence antigen expression within latently infected ganglia may have on the persisting CD8+ T-cell population. We utilized the flank scarification model to study the infiltration and persistence of CD8+ T cells in the ganglia during HSV-1 infection, focusing on the importance of T-cell specificity and the role the neuronal parenchyma play in maintaining T-cell activation during latency. These experiments demonstrate that while both specific and nonspecific CD8+ T cells infiltrate and persist within HSV-infected sensory ganglia, only the former will maintain an activated phenotype consistent with their ongoing stimulation by the infected neuronal cells themselves.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and viruses.

C57BL/6, B6.SJL-PtprcaPep3b/BoyJ (B6.Ly5.1), gBT-I, gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1, OT-I, OT-I × B6.Ly5.1, and B6-H-2bm3 female mice were purchased from the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, The University of Melbourne Animal House, and housed in specific-pathogen-free conditions. C57BL/6 mice express the leukocyte surface antigen CD45.2 or Ly5.2, and B6.SJL-PtprcaPep3b/BoyJ (B6.Ly5.1) mice express the congenic marker CD45.1 or Ly5.1. The OT-I and gBT-I mice are T-cell receptor (TCR)-transgenic mice that recognize the H-2Kb-restricted ovalbumin (OVA)-derived epitope OVA257-264 (SIINFEKL) and the HSV-1 glycoprotein B (gB) epitope gB498-505 (SSIEFARL), respectively (27, 42). The gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1 and OT-I × B6.Ly5.1 mice are F1 generations of each respective cross; these mice have both the Ly5.1(CD45.1) and Ly5.2(CD45.2) alleles. B6-H-2bm3 mice are unable to present the HSV-1-derived gB498-505 epitope to gBT-I T-cells due to a mutation in the Kb molecule (43) and have the Ly5.2 allele. The KOS strain of HSV-1 (provided by S. Person, Johns Hopkins University) was grown and titrated by plaque assay on Vero cells (CSL, Parkville, Australia) in MEM10 (minimal essential medium with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum [FCS], 23.83 g/liter HEPES, 4 mM l-glutamine, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol [ME], and antibiotics). Stocks were stored at −70°C until required.

Generation of chimeras.

C57BL/6, B6.Ly5.1, and B6-H-2bm3 mice were irradiated with two doses of 550 cGray. The mice were immediately reconstituted via intravenous (i.v.) injection of 5 × 106 bone marrow cells obtained from the tibias and femurs of either B6.Ly5.1 or B6-H-2bm3 mice in a total volume of 150 μl Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS). Mice were kept in microisolator cages with sterile sawdust and food and were given water containing neomycin sulfate (25 mg/liter) and polymyxin B sulfate (76,900 U/liter). They were allowed to reconstitute for 8 weeks before use.

HSV-1 infections.

Mice were infected on the flank with 106 PFU of HSV-1 using the flank scarification method described previously (2, 58). In brief, mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (100 mg/kg of body weight) (Parnell Laboratories, Alexandria, Australia)-Ilium Xylazil-20 (20 mg/kg body weight) (Troy Laboratories, Smithfield, Australia) in saline. Hair was removed from the left flank of the animals, and a small area of skin, reproducibly located by means of visualizing the dorsal tip of the spleen under the intact skin, was abraded using a MultiPro power tool (Dremel, Racine, WI) with a grindstone attachment (3.2 mm) held on the skin for 15 s. A 10-μl aliquot of virus (106 PFU) was placed on the abraded skin and rubbed in with a cotton-tipped applicator soaked in phosphate-buffered saline. The inoculation site was covered with a piece of OpSite Flexigrid (Smith & Nephew, Hull, United Kingdom), and the mice were then bandaged with Micropore tape and then Transpore tape (3M Health Care, St. Paul, MN). The tape and Flexigrid were removed 48 h following infection.

Adoptive transfer of naïve CD8+ T cells.

Lymph node cells were obtained from naïve gBT-I, gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1, OT-I, or OT-I × B6.Ly5.1 mice. Approximately 5 × 104 CD8+ T cells, as determined by flow cytometry, were transferred into recipient mice via i.v. injection in a total volume of 200 μl HBSS at the times indicated.

Adoptive transfer of activated CD8+ T cells.

A total of 5 × 107 transgenic splenocytes (from gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1 and OT-I × B6.Ly5.1 mice) were cultured for 4 days with 5 × 107 C57BL/6 splenocytes pulsed with 0.1 μg of the relevant peptide, either gB498-505 or OVA257-264, in 40 ml of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 5 mM HEPES, 2 mM glutamine, 5 × 10−5 M 2-ME, antibiotics, and 6 μg lipopolysaccharide (Escherichia coli 0111:B4; Sigma). Cultures were diluted 1:2 on day 2 and again on day 3 with fresh medium containing 10 U/ml interleukin-2. On day 4, cells were collected, and 107 CD8+ T cells were transferred into recipient mice via i.v. injection in a total volume of 200 μl HBSS.

Identifying CD8+ T cells in the dorsal root ganglia (DRGs).

Mice were sacrificed and perfused with phosphate-buffered saline, and the ganglia innervating the site of cutaneous inoculation were removed with the aid of a dissecting microscope. The DRGs collected from a single mouse were pooled in 0.5 ml of collagenase type 3 (Worthington) at 3 mg/ml in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% FCS. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 1.5 h and dispersed into single-cell suspensions with trituration at both 1 and 1.5 h. Anti-CD8α-allophycyanin (APC) (53-6.7), anti-CD45.1-phycoerythrin (PE) (A20), and anti-CD45.2-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (104) were obtained from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1 and OT-I × B6.Ly5.1 CD8+ T cells were generally identified by staining with anti-CD8-APC and anti-CD45.1-PE (in chimera experiments these cells were identified by staining with anti-CD8-APC, anti-CD45.1-PE, and anti-CD45.2-FITC). Staining was performed on ice in the dark for 30 min. To identify OT-I CD8+ T cells, samples were first stained on ice with anti-CD8 and then at 37°C with OVA-specific tetramer, prepared as previously described (3) and provided by Martha Kotsifas (University of Melbourne). Prior to analysis, all samples received 5 μl EDTA (0.5 M) and 10 μl propidium iodine (50 μg/ml) to prevent clumping and enable exclusion of dead cells, respectively. A known quantity of blank calibration beads was also added to each sample in a total volume of 20 μl to enable the number of cells to be determined. Cells were analyzed on a FACScalibur using Cell ProQuest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

CD69 and intracellular granzyme B staining.

To determine CD69 expression, DRG samples were prepared as described above. Anti-CD8-APC (53-6.7), anti-CD69-PE (H1-2F3), anti-CD45.1-biotin (A20), and streptavidin-FITC were obtained from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Cells were stained on ice for 30 min first with anti-CD8-APC, anti-CD45.1-biotin, and anti-CD69-PE and then with streptavidin-FITC. Propidium iodine (10 μl at 50 μg/ml) for dead cell exclusion and the same number of blank calibration beads (approximately 2,000 beads) for cell number determination were added to all samples prior to analysis. Cells were analyzed on a FACScalibur using Cell ProQuest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). To determine the levels of preformed granzyme B, DRG samples were again prepared as described above. Blood was obtained from the tail vein of mice that had been warmed for 5 min on a light box and collected directly into microcentrifuge tubes containing 20 μl heparin. Red blood cells were lysed by diluting samples in 7.5 ml water followed by the immediate addition of 2.5 ml 4× saline. Anti-CD8-peridinin chlorophyll-a protein (PerCP) (53-6.7) was obtained from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA), and anti-human granzyme B-APC was obtained from Caltag (Burlingame, CA). Cells were stained with anti-CD8-PerCP, anti-CD45.1-PE, and anti-CD45.2-FITC on ice for 30 min. Cells were then fixed in 1% formaldehyde (Ajax, Queensland, Australia) for 20 min at room temperature and then stained with anti-human granzyme B-APC in the presence of 0.2% saponin (Sigma) for 1 h at 4°C. Blank calibration beads were added to each DRG sample to enable the number of cells to be determined. Cells were analyzed on a FACScalibur using Cell ProQuest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

RESULTS

HSV-specific CD8+ T cells persist in the ganglia of C57BL/6 mice during latency following HSV-1 flank scarification infection.

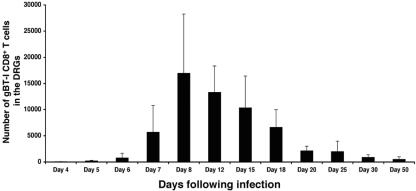

CD8+ T cells have been shown to persist in latently infected sensory ganglia in both animals and humans (29, 35, 54). Using a flank scarification model of infection, we had found that lytic virus is detected in those dorsal root ganglia (DRGs) innervating the site of cutaneous inoculation from days 2 to 7 postinfection (p.i.) (58). Virus replication was accompanied by a steady influx of T cells specific for a determinant from the glycoprotein B (gB498-505) found to be immunodominant in the C57BL/6 strain of mouse (9, 24, 59). Further experiments established that a latent infection persists within these DRGs capable of reactivation following ex vivo culture (data not shown). To determine whether the HSV-specific CD8+ T cells were being retained following clearance of infectious virus, C57BL/6 mice received naïve gBT-I CD8+ T cells prior to infection. These HSV-specific transgenic T cells are easily identified by their expression of the congenic marker Ly5.1 and allowed tracking of anti-viral CD8+ T cells. Mice were infected on the flank with HSV-1, and the ganglia innervating the site of cutaneous infection were analyzed via flow cytometry for the presence of gB-specific CD8+ T cells at various time points postinfection (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Persistence of CD8+ T cells in the DRGs during latent HSV-1 infection. A cohort of C57BL/6 mice received 5 × 104 resting gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1 CD8+ T cells 24 h prior to flank scarification infection. Groups of 4 to 12 mice were then sacrificed at various time points following infection, and the DRGs innervating the site of cutaneous infection were analyzed via flow cytometry for the presence of gB-specific CD8+ T cells. The average number of gB-specific CD8+ T cells obtained from an individual mouse is shown. Lytic virus has previously been shown to clear from the DRGs by days 7 to 8 postinfection, leaving a persistent latent infection.

As shown, low numbers of gB-specific CD8+ T cells were first detected in the DRGs on day 5 postinfection, indicating that ganglionic infiltration by the CD8+ T cells occurred during the lytic phase of infection, consistent with previous studies (35, 48, 58). The number of T cells within the DRGs reached a peak between days 8 and 12 postinfection just after elimination of infectious virus from this site, which occurs around days 7 to 8 (Fig. 1 and reference 58). This is effectively the start of the latent phase of infection. While there was considerable loss of infiltrating T cells from peak levels, a relatively stable number of gB-specific T cells could still be detected within the DRGs between 20 to 50 days postinfection, indicating that virus-specific T cells were retained during latency following flank scarification infection.

The antigen specificity and activation requirements for CD8+ T-cell infiltration within the peripheral nervous system.

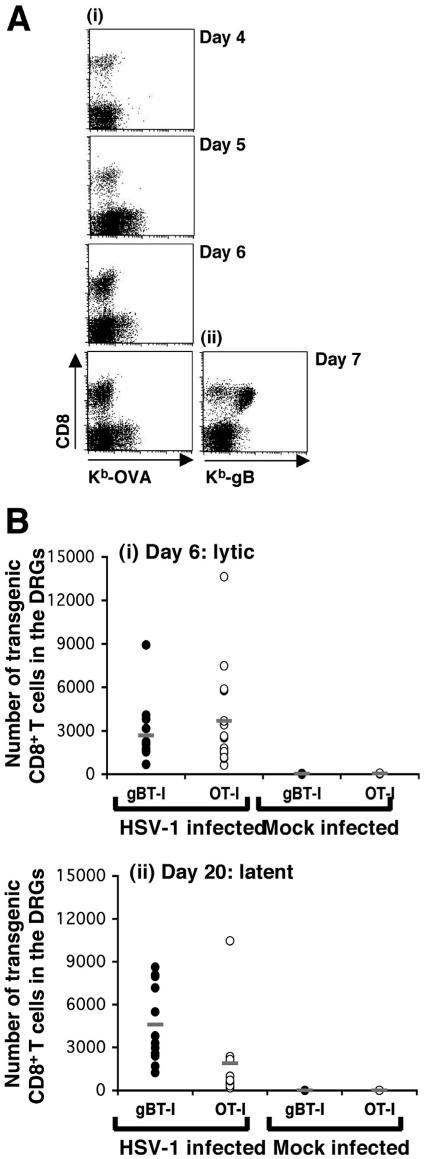

To determine the relative importance of antigen specificity to this T-cell infiltration, we used CD8+ T cells from OT-I mice which are specific for the OVA257-264 epitope from ovalbumin (OVA) and do not recognize the gB epitope from HSV-1 (56). We investigated the ability of both resting and activated OT-I CD8+ T cells to infiltrate the ganglia during acute infection and then be retained during latency. Initially, naive OT-I CD8+ T cells were transferred into recipient C57BL/6 mice 24 h prior to flank infection, and the DRGs were analyzed for T-cell infiltration on days 4 to 7. As shown in Fig. 2A, OVA-specific CD8+ T cells were not detected in the DRGs of these animals while gB-specific T cells were, showing that without prior activation, T cells of irrelevant specificity failed to infiltrate infected tissues.

FIG. 2.

Infiltration and persistence of OT-I CD8+ T cells in the DRGs following flank scarification infection. (A) A cohort of C57BL/6 mice received 5 × 104 resting OT-I CD8+ T cells 24 h prior to flank scarification infection. Groups of four mice were then sacrificed on days 4 to 7 p.i., and the DRGs innervating the site of cutaneous infection were analyzed via flow cytometry for the presence of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells. Cells were stained with anti-CD8 and Kb-OVA tetramer to identify the double-positive OT-I CD8+ T cells. A positive control group of four mice that had received resting gBT-I CD8+ T cells prior to flank infection were also analyzed on day 7 postinfection; these samples were stained with anti-CD8 and Kb-gB tetramer. (B) C57BL/6 mice were infected on the flank with HSV-1 and then received either 107 in vitro-activated gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1 or 107 in vitro-activated OT-I × B6.Ly5.1 CD8+ T cells on day 4 postinfection. Mice in each group were sacrificed on day 6 and day 20 p.i., lytic and latent time points, respectively. The DRGs innervating the site of cutaneous inoculation were removed from the mice at each time point and treated with collagenase, and the released cells were stained with anti-CD8 and anti-Ly5.1 and analyzed via flow cytometry for the presence of transgenic CD8+ T cells. The number of gB-specific (closed circles, n = 14 and 8 for infected and mock-infected mice, respectively) or OVA-specific (open circles, n = 17 and 8 for infected and mock-infected mice) CD8+ T cells in the DRGs on day 6 (i) and day 20 (n = 12 and 11 for gB and OVA specific T cells, respectively, into infected mice, and n = 4 for both sets of mock-infected mice) (ii) is shown for each mouse, with averages indicated (−). Mock-infected animals received in vitro-activated gB-specific or OVA-specific CD8+ T cells on day 4 p.i.

At face value, the preceding results argued that the OT-I T cells were unable to infiltrate infected ganglia. However, these cells are not primed during the infection, so a better assessment of their infiltrating capabilities involves the use of already activated OT-I cells. To this end, CD8+ T cells from OT-I mice and control gBT-I animals were stimulated in vitro for 4 days and then transferred into separate groups of C57BL/6 mice on day 4 after flank scarification infection. This timing mimics the normal release of virus-specific CD8+ T cells from draining lymph nodes following HSV-1 infection (13). The infiltration of these transferred cells into the DRGs was analyzed on day 6 postinfection, as was their presence on day 20, by which time all viral replication has subsided in these mice (58).

Figure 2B shows that similar numbers of activated gB- and OVA-specific CD8+ T cells infiltrated the ganglia during the acute infection. An average of 2,700 and 3,700 activated gBT-I and OT-I cells, respectively, were found to infiltrate infected ganglia at the acute day 6 time point compared to no infiltrating T cells in the mock-infected controls. T-cell infiltration was seen at day 20 postinfection, which is beyond the time required to clear infectious virus (58). The nonspecific OT-I infiltrate was reduced compared to the specific gBT (averages of 1,900 cells and 4,600 cells, respectively), although even this level of nonspecific infiltration was significantly greater than that seen in noninfected control mice, where again no infiltrating T cells were detected. Overall, the results in Fig. 1 and 2 suggested that T-cell infiltration into the DRGs, at least during the lytic phase of infection, does not appear to be dependent on antigen specificity but rather requires that the cells had undergone previous activation. Moreover, the results also suggested that specificity for virus is not required for the persistence of T-cell infiltration into the latent phase of infection, although virus recognition may result in elevated T-cell numbers at this time.

The infiltration of activated CD8+ T cells in sensory ganglia during latent infection.

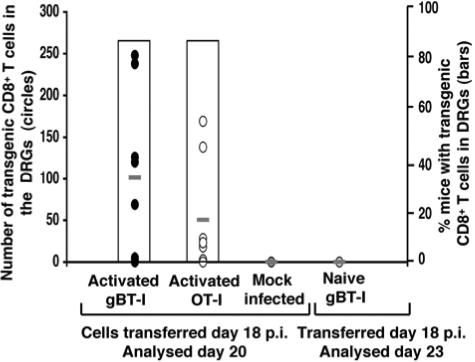

The infiltration of specific T cells and those of irrelevant specificities (bystander T cells) during latency could simply reflect carryover from the lytic phase of infection. We therefore sought to investigate whether these same cells could infiltrate the sensory ganglia during latency when no replicating virus was present. We infected a cohort of C57BL/6 mice and transferred in vitro-activated gBT-I or OT-I CD8+ T cells into separate groups of these mice on day 18 postinfection, when lytic virus had been cleared. We then analyzed the DRGs on day 20 postinfection (Fig. 3). Both activated gBT-I and OT-I cells infiltrated the ganglia of most latently infected mice. Slightly higher numbers of activated gBT-I T cells were detected, although the numbers for both populations were clearly lower than those seen during the lytic infection (Fig. 2B). No transgenic cells were seen in the ganglia of mock-infected mice, indicating a requirement for infection.

FIG. 3.

Infiltration of CD8+ T cells into the DRGs during HSV-1 latency. A cohort of C57BL/6 mice was infected on the flank with HSV-1. On day 18 p.i., when lytic virus had been cleared and latency established, the mice received either 107 in vitro-activated gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1 (n = 8) or 107 in vitro-activated OT-I × B6.Ly5.1 (n = 8). The mice were then sacrificed on day 20 p.i., and the DRGs innervating the site of cutaneous infection were analyzed for transgenic CD8+ T cells via flow cytometry. Cells were stained with anti-CD8 and anti-Ly5.1. The number of gB-specific (closed circles) or OVA-specific (open circles) CD8+ T cells is shown for each mouse, with averages indicated (−). The percentage of mice that were positive for transgenic T cells in their DRGs is also shown (open bars). Two negative control groups were included in this experiment. First, mock-infected animals that received 107 in vitro-activated gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1 or OT-I × B6.Ly5.1 CD8+ T cells on day 18 after mock infection. The DRGs from these mice were analyzed on day 20 postinfection. Second, HSV-1-infected C57BL/5 mice that received resting gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1 CD8+ T cells on day 18 p.i. The DRGs from these mice were analyzed for transgenic T-cell infiltration on day 23 p.i. (5 days posttransfer).

To demonstrate a requirement for activation, we additionally investigated whether gB-specific cells transferred in a naïve state would infiltrate the ganglia during latency, as shown during the acute infection (Fig. 1). Naïve gBT-I CD8+ T cells were transferred into C57BL/6 mice that had been infected on the flank with HSV-1 18 days earlier, and then DRGs were analyzed on day 23, 5 days after transfer (Fig. 3). In this case, no cells were detected in the sensory ganglion, suggesting that with the clearance of the lytic infection, naïve gBT-I T cells themselves could not enter the ganglia, nor could they be activated in vivo and then enter as activated cells.

The activation status of CD8+ T cells within the sensory ganglia during lytic and latent infection.

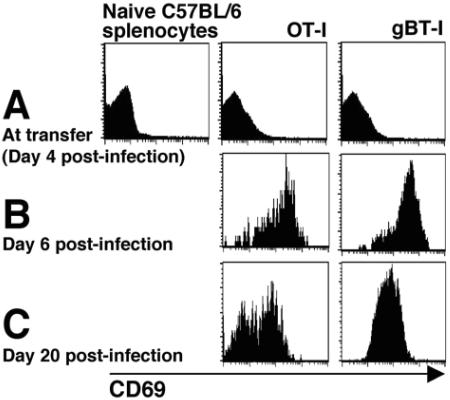

Previous reports have demonstrated that HSV-specific CD8+ T cells retained in the ganglia during latency exhibit an activated phenotype (29, 54). Since these earlier reports did not demonstrate that expression of activation markers was exclusive to virus-specific T cells within the DRGs, we sought to determine whether nonspecific infiltrates could also express acute activation markers.

Initially, we analyzed the expression of CD69, a marker used to support the idea that T cells retained within latently infected sensory ganglia are undergoing antigenic stimulation (29). In vitro-activated gBT-I and OT-I CD8+ T cells were transferred into C57BL/6 mice on day 4 following infection. The DRGs were removed on days 6 and 20 postinfection, and the infiltrating T cells were analyzed for their expression of CD69 (Fig. 4). At the lytic time point, day 6 postinfection (Fig. 4B), both the gB- and OVA-specific CD8+ T cells found within the sensory ganglia expressed high levels of CD69. It should be noted, however, that the T cells did not express CD69 at the time of transfer (Fig. 4A), therefore, this upregulation occurred in vivo. At the latent time point, day 20 postinfection (Fig. 4C), all the gBT-I CD8+ T cells and approximately 50% of the OT-I CD8+ T cells still expressed high levels of CD69.

FIG. 4.

CD69 expression on CD8+ T cells in HSV-infected DRGs. CD8+ T cells from gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1 and OT-I × B6.Ly5.1 mice were stimulated in vitro for 4 days. Following this stimulation, the cells were analyzed for their expression of the early activation marker, CD69, compared to naïve C57BL/6 CD8+ T cells (A). The activated T cells were then transferred into separate groups of C57BL/6 mice that had been infected on the flank with HSV-1 4 days earlier (107 cells per mouse). The gB-specific and OVA-specific CD8+ T cells that were isolated from the DRGs on day 6 p.i. (B) and day 20 p.i. (C) were analyzed for their expression of CD69.

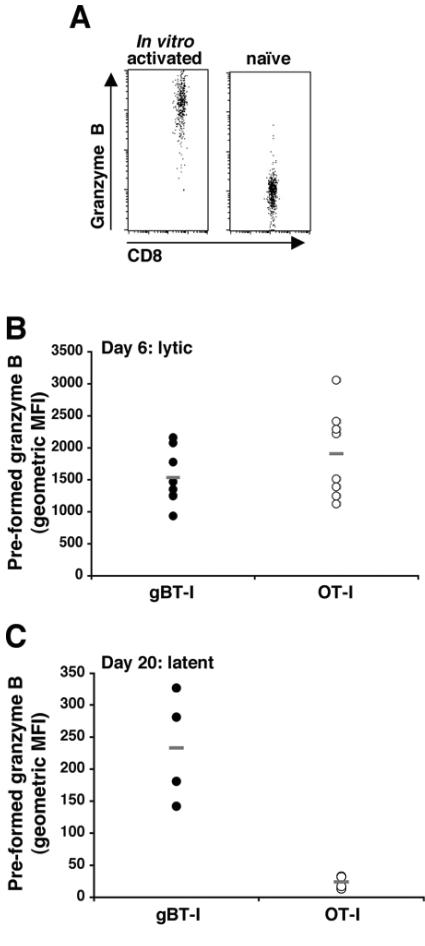

Wherry et al. (60) have shown that granzyme B levels rapidly decline during contraction into memory populations, and these levels are rapidly upregulated on encountering the target antigen (61). Given this, we analyzed the levels of preformed granzyme B in each cell population at the same time points. As controls, in vitro-activated and naïve gBT-I cells were shown to express high versus low levels of granzyme B, respectively (Fig. 5A), and subsequent analysis is expressed as the mean fluorescence intensity of granzyme B profiles. Similar to CD69 expression, both the gBT-I and OT-I CD8+ T cells within the DRGs had high levels of preformed granzyme B at the lytic time point, day 6 postinfection (Fig. 5B), although it should be noted that both populations were granzyme positive at transfer (an example is given in Fig. 5A for the gBT-I cells). Of the T cells retained in the DRGs at the latent time point, only the gB-specific T cells had high levels of preformed granzyme B (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that while both specific and nonspecific cells are retained within latently infected ganglia, the HSV-specific CD8+ T cells are preferentially maintained in an activated state as measured by granzyme B expression.

FIG. 5.

Preformed granzyme B in CD8+ T cells in HSV-infected DRGs. CD8+ T cells from gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1 and OT-I × B6.Ly5.1 mice were stimulated in vitro for 4 days and then analyzed for their levels of preformed granzyme B via flow cytometry. An example is shown of in vitro-activated gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1 compared to naïve C57BL/6 CD8+ T cells (A). The activated T cells were then transferred into separate groups of C57BL/6 mice that had been infected on the flank with HSV-1 4 days earlier (107 cells per mouse). The DRGs were removed from these mice on day 6 (B) and day 20 (C) p.i. The gB-specific (closed circles) and OVA-specific (open circles) CD8+ T cells that were isolated from the DRGs at each time point were analyzed for their levels of preformed granzyme B. The results are presented as the geometric mean of fluorescence intensity (MFI); averages are indicated (−). The difference in scale between the two time points is due to a different batch of anti-human granzyme B antibody being used.

The role of the parenchyma in the persistence of CD8+ T cells within the peripheral nervous system during HSV-1 latency.

The finding that HSV-specific CD8+ T cells were preferentially maintained in an activated state within latently infected sensory ganglia suggested that some form of antigen presentation must exist within those tissues harboring latent infection. Given this possibility, we wanted to verify the existence of such presentation and determine whether it involved the parenchymal cells within the ganglia or bone marrow-derived antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells. To investigate this, we utilized three different groups of chimeric mice: B6.Ly5.1 (donor) into C57BL/6 (recipient), termed B6.Ly5.1→B6; B6.Ly5.1 into B6-H-2bm3, termed B6.Ly5.1→bm3; and B6-H-2bm3 into B6.Ly5.1, termed bm3→B6.Ly5.1. The congenic difference at the Ly5.1 genetic locus between host and recipient cells allowed us to ensure that host mice had been fully reconstituted with the donor bone marrow. The B6.Ly5.1→B6 chimeras provided a situation where both the bone marrow-derived APCs and the host parenchyma were capable of presenting the gB epitope to gBT-I CD8+ T cells. The B6.Ly5.1→bm3 chimeras had APCs that could present the gB epitope to gBT-I CD8+ T cells but had parenchymal cells, including infected neuronal cells, that could not, due to a mutation in the H-2Kbm3 MHC class I molecule (43). Finally, in the bm3→B6.Ly5.1 chimeras the host parenchymal cells could present the gB epitope while the APCs could not, providing a situation whereby the HSV-1 infection would fail to activate the gB-specific T cells in the periphery, thus preventing their initial infiltration into the ganglia.

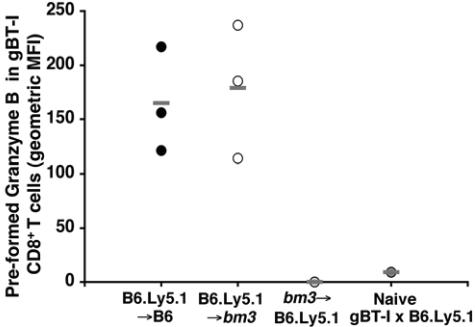

Prior to infection, the chimeras were seeded with naïve gBT-I CD8+ T cells expressing both Ly5.1 and Ly5.2, allowing their distinction from C57BL/6, B6.Ly5.1, and bm3 cells present in the chimeras. Blood from these animals was analyzed on day 9 postinfection to determine whether the transferred T cells were responding to the infection. As shown in Fig. 6, the transgenic gB-specific T cells were detected in the blood of the B6.Ly5.1→B6 and B6.Ly5.1→bm3 chimeric mice on day 9 postinfection and were found to contain high levels of preformed granzyme B compared to naïve gBT-I cells. The transgenic cells could not be detected in the blood of the bm3→B6.Ly5.1 chimeras, suggesting that, as expected, the gB-specific T cells were not responding to the HSV-1 infection in the absence of professional APCs bearing the responder Kb restriction element.

FIG. 6.

In vivo activation of gBT-I CD8+ T cells following flank scarification infection. B6.Ly5.1→B6, B6.Ly5.1→bm3, and bm3→B6.Ly5.1 bone marrow chimeras were seeded with 5 × 104 resting gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1 CD8+ T cells 24 h prior to flank scarification infection. On day 9 p.i., blood was collected from these mice and the gB-specific CD8+ T cells in the blood were analyzed for their level of activation, as determined by their level of preformed granzyme B. Blood from naïve gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1 mice was also analyzed as a negative control. The results are presented as the geometric mean of fluorescence intensity (MFI), with averages indicated (−).

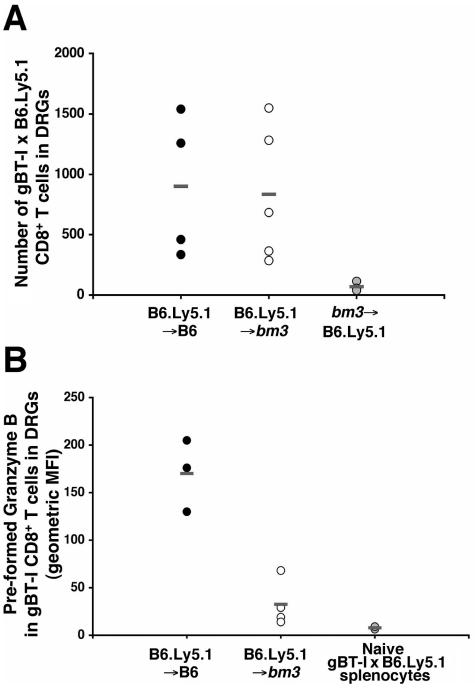

The infected chimeras were then left until 30 to 35 days postinfection, allowing the lytic infection to clear and latency to be established. At this point the DRGs were analyzed to determine transgenic T-cell numbers and their activation status, based on preformed granzyme B levels. As shown in Fig. 7A, similar numbers of transgenic T cells were seen in the ganglia of the B6.Ly5.1→B6 and B6.Ly5.1→bm3 chimeric mice, suggesting that presentation by the neuronal parenchyma was not required for T-cell infiltration during latency, consistent with our earlier results showing OT-I T-cell retention (Fig. 2B). As expected, no gB-specific T cells were seen in the ganglia of the bm3→B6.Ly5.1 mice, since the cells were not activated in this particular bone marrow replacement chimera. Interestingly, analysis of the activation status of the gB-specific T cells in the DRGs of the two infiltrated chimeras found that only the cells in B6.Ly5.1→B6 mice maintained high levels of preformed granzyme B (Fig. 7B), with T cells in the ganglia of B6.Ly5.1→bm3 mice losing granzyme B expression seen during acute infection (Fig. 6). These results suggested that maintenance of an activated phenotype by the specific T cells retained within latently infected ganglia was dependent on antigen expression by parenchymal cells within the ganglia.

FIG. 7.

The role of parenchymal cells in the infiltration and activation of gB-specific CD8+ T cells in the peripheral nervous system during HSV-1 latency. B6.Ly5.1→B6, B6.Ly5.1→bm3, and bm3→B6.Ly5.1 bone marrow chimeras were seeded with 5 × 104 resting gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1 CD8+ T cells 24 h prior to flank scarification infection. On days 30 to 35 p.i. the mice were sacrificed and the DRGs innervating the site of cutaneous infection were removed. (A) The number of gB-specific CD8+ T cells in the DRGs of each mouse was determined using flow cytometry. The results for each individual mouse are shown with averages indicated (−). (B) The gB-specific CD8+ T cells within the DRGs were also analyzed for their levels of preformed granzyme B. The results are presented as the geometric mean of fluorescence intensity (MFI), with averages indicated (−). Resting gBT-I × B6.Ly5.1 CD8+ T cells were included in this analysis as a negative control. There was no granzyme B analysis for the bm3→B6.Ly5.1 chimeras, as gB-specific CD8+ T cells were not detected in the DRGs of these mice.

DISCUSSION

Skin infection with herpes simplex virus involves the activation of CD8+ T cells within draining lymph nodes followed by their migration to sites of infection, including the sensory ganglia, where they act to clear infectious virus (8, 13, 20, 33, 41, 49, 58). Here we show that these infiltrating T cells persist beyond the cessation of lytic infection, well into latency, consistent with other studies (29, 54). It has been suggested that some level of viral antigen expression occurs within ganglia harboring latent infection. This hypothesis was based on a number of findings. First, HSV-specific CD8+ T cells are retained within latently infected ganglia and exhibit an activated phenotype, namely CD69 expression (29) and cytokine production (10, 23). Second, viral replication and reactivation are not required to maintain the activated phenotype (12). Third, the retained T cells localize to the neurons within the ganglion (10, 29), previously shown to be the reservoir for latent virus within nervous tissue (40, 46). Our results demonstrate that the presence of at least partly activated T cells within ganglia is not sufficient to assume that viral antigen expression is occurring. Put simply, T cells bearing irrelevant specificities, otherwise known as bystander T cells, will infiltrate acutely infected ganglia and then be retained during latency, where they continue to express CD69.

With regard to the infiltration of T cells into the peripheral nervous system, our results suggest that the activation status of the cells is more important than their specificity, implying that the inflammation associated with HSV infection is a key stimulus for T-cell entry. This hypothesis is supported by a number of studies with other viruses that have provided evidence for infiltration of activated bystander T cells (7, 11, 26, 28, 55), confirming that it is indeed usual for such T cells to infiltrate sites of localized infection. Our results extend this notion of nonspecific infiltration beyond the lytic phase of HSV infection, suggesting that the entry stimuli exist in the absence of overt virus replication. At this time we are unable to determine whether ganglionic T cells are newly recruited from the circulation or self renewing within that latent ganglia. The ability of activated T cells to traffic into ganglia after lytic infection has subsided, seen in Fig. 3, argues that some level of replacement is possible even late in infection.

The observed bystander T-cell infiltration caused us initial concern, since it suggested that the mere presence of T cells during the period of latency did not automatically translate to ongoing T-cell stimulation and corresponding antigen expression. As a consequence, we thought it important to clearly establish that while both specific and nonspecific T cells persist in ganglia harboring latent HSV infections, only virus-specific T cells showed unequivocal evidence for continuing antigen-specific stimulation. Our results demonstrate this using granzyme B, since only the virus-specific T cells retained within latently infected ganglia expressed this activation marker. While CD69 is rapidly upregulated on TCR engagement (62), its expression on bystander OT-I T cells suggests caution should be exercised when attributing this solely to antigen-specific activation events. Other investigators have reported CD69 expression in persisting T-cell infiltrates, especially following infections of the central nervous system (25, 36, 37, 57). This was largely assumed to result from antigen expression below levels detectable using biochemical means. However, interferon-α/β can partially activate T cells in an antigen-independent manner resulting in CD69 expression (53), which could explain its presence on bystander cells during HSV latency. Also of interest in the context of HSV, other researchers have proposed that the pathology associated with herpetic stromal keratitis can be induced by infiltrating bystander transgenic T cells (4, 17), presumably as a result of some form of nonspecific activation within the eye that may be analogous to what is seen here in the infected ganglia.

The bone barrow chimeras reinforce that antigen-specific T-cell stimulation is maintained during the period of latent infection. Moreover, this effect appeared dependent on antigen presentation by the neuronal parenchyma, which includes the latently infected neurons. Thus, our results support the original hypothesis that antigen expression does persist into latency (10). The chimeras exclude the involvement of local bone marrow-derived antigen-presenting cells, most notably dendritic cells, in this prolonged activation. This exclusion is especially important, since Delamarre et al. (16) recently showed that dendritic cells appear to retain antigen for prolonged periods and thus could have provided ongoing local presentation carried over from the lytic phase of infection.

In total, our results argue that latency is far from silent as far as the adaptive immune response is concerned, although it is clearly different to the lytic phase of infection. The ability to prime new T-cell responses does not appear to extend beyond the third week of infection, since resting T cells, but not their activated counterparts, failed to enter ganglia at this time. This is well after the cessation of the early phase of infection with its period of overt virus replication. This lack of stimulation of naïve but not activated T cells within the ganglia fits with the notion that dendritic cells, critical for CD8+ T-cell priming (2, 6, 50), are no longer involved in T-cell activation, highlighting the immunological difference between the lytic and latent phases of infection.

At face value, the sheer presence of armed, virus-specific T cells apparently capable of destroying infected neurons and clearly reacting to ongoing antigen presentation appears at odds with the persistence of virus-infected cells within the ganglia. This has led to the proposal that neurons harboring latent infection are protected from the full force of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte recognition (31). Simmons and Tscharke (49) originally proposed the notion of nonlethal T-cell interaction with neurons and suggested that, if anything, more neurons died in the absence of CD8+ T cells. Features such as the observed low major histocompatibility complex class I expression on latently infected neurons (44), the proposed anti-apoptotic action of the LAT transcripts (1, 45), or other protective mechanisms could all contribute to cell survival and thus the persistence of latent virus in the face of a fully armed immune response.

While our findings do not directly address the role of activated T cells during latency, they suggest these cells are poised to rapidly deal with emerging virus during the early stages of HSV reactivation. Regardless of whether the persisting T cells limit reactivation as suggested by Khanna and colleagues (29, 34), they are unlikely to remain inert during this process since they are capable of shutting down lytic replication within the ganglia (20, 49, 58). Therefore, in order to permit replication to occur, these cells must be overwhelmed in some fashion by the reemerging virus. The ganglion-resident T cells are likely to be effector-memory cells, which are known to infiltrate peripheral tissues (38, 39, 47). Effector-memory cells reexpand poorly to further stimulation (60), and this sluggish ability to respond could explain their ineffective control of reactivating virus. Further studies on persisting T cells, focusing on their fate during this stage of HSV infection, will provide us with a better understanding of the mechanisms that lead to virus reactivation from its latent phase of infection.

.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NHMRC program grant 208981.

We thank Claerwen Jones for careful review of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ahmed, M., M. Lock, C. G. Miller, and N. W. Fraser. 2002. Regions of the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript that protect cells from apoptosis in vitro and protect neuronal cells in vivo. J. Virol. 76:717-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allan, R. S., C. M. Smith, G. T. Belz, A. L. van Lint, L. M. Wakim, W. R. Heath, and F. R. Carbone. 2003. Epidermal viral immunity induced by CD8α+ dendritic cells but not by Langerhans cells. Science 301:1925-1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altman, J. D., P. A. Moss, P. J. Goulder, D. H. Barouch, M. G. McHeyzer-Williams, J. I. Bell, A. J. McMichael, and M. M. Davis. 1996. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science 274:94-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee, K., P. S. Biswas, U. Kumaraguru, S. P. Schoenberger, and B. T. Rouse. 2004. Protective and pathological roles of virus-specific and bystander CD8+ T cells in herpetic stromal keratitis. J. Immunol. 173:7575-7583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baringer, J. R., and P. Swoveland. 1973. Recovery of herpes-simplex virus from human trigeminal ganglions. N. Engl. J. Med. 288:648-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belz, G. T., C. M. Smith, D. Eichner, K. Shortman, G. Karupiah, F. R. Carbone, and W. R. Heath. 2004. Cutting edge: conventional CD8α+ dendritic cells are generally involved in priming CTL immunity to viruses. J. Immunol. 172:1996-2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergmann, C. C., J. D. Altman, D. Hinton, and S. A. Stohlman. 1999. Inverted immunodominance and impaired cytolytic function of CD8+ T cells during viral persistence in the central nervous system. J. Immunol. 163:3379-3387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaney, J. E., Jr., E. Nobusawa, M. A. Brehm, R. H. Bonneau, L. M. Mylin, T. M. Fu, Y. Kawaoka, and S. S. Tevethia. 1998. Immunization with a single major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted cytotoxic T-lymphocyte recognition epitope of herpes simplex virus type 2 confers protective immunity. J. Virol. 72:9567-9574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonneau, R. H., L. A. Salvucci, D. C. Johnson, and S. S. Tevethia. 1993. Epitope specificity of H-2Kb-restricted, HSV-1-, and HSV-2-cross-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocyte clones. Virology 195:62-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantin, E. M., D. R. Hinton, J. Chen, and H. Openshaw. 1995. Gamma interferon expression during acute and latent nervous system infection by herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 69:4898-4905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, A. M., N. Khanna, S. A. Stohlman, and C. C. Bergmann. 2005. Virus-specific and bystander CD8 T cells recruited during virus-induced encephalomyelitis. J. Virol. 79:4700-4708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, S. H., D. A. Garber, P. A. Schaffer, D. M. Knipe, and D. M. Coen. 2000. Persistent elevated expression of cytokine transcripts in ganglia latently infected with herpes simplex virus in the absence of ganglionic replication or reactivation. Virology 278:207-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coles, R. M., S. N. Mueller, W. R. Heath, F. R. Carbone, and A. G. Brooks. 2002. Progression of armed CTL from draining lymph node to spleen shortly after localized infection with herpes simplex virus 1. J. Immunol. 168:834-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Croen, K. D., J. M. Ostrove, L. J. Dragovic, and S. E. Straus. 1988. Patterns of gene expression and sites of latency in human nerve ganglia are different for varicella-zoster and herpes simplex viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:9773-9777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deatly, A. M., J. G. Spivack, E. Lavi, and N. W. Fraser. 1987. RNA from an immediate early region of the type 1 herpes simplex virus genome is present in the trigeminal ganglia of latently infected mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:3204-3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delamarre, L., M. Pack, H. Chang, I. Mellman, and E. S. Trombetta. 2005. Differential lysosomal proteolysis in antigen-presenting cells determines antigen fate. Science 307:1630-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deshpande, S., M. Zheng, S. Lee, K. Banerjee, S. Gangappa, U. Kumaraguru, and B. T. Rouse. 2001. Bystander activation involving T lymphocytes in herpetic stromal keratitis. J. Immunol. 167:2902-2910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman, L. T., A. R. Ellison, C. C. Voytek, L. Yang, P. Krause, and T. P. Margolis. 2002. Spontaneous molecular reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 latency in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:978-983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gebhardt, B. M., and J. M. Hill. 1988. T lymphocytes in the trigeminal ganglia of rabbits during corneal HSV infection. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 29:1683-1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghiasi, H., G. Perng, A. B. Nesburn, and S. L. Wechsler. 1999. Either a CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell function is sufficient for clearance of infectious virus from trigeminal ganglia and establishment of herpes simplex virus type 1 latency in mice. Microb. Pathog. 27:387-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon, Y. J., B. Johnson, E. Romanowski, and T. Araullo-Cruz. 1988. RNA complementary to herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP0 gene demonstrated in neurons of human trigeminal ganglia. J. Virol. 62:1832-1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green, M. T., R. J. Courtney, and E. C. Dunkel. 1981. Detection of an immediate early herpes simplex virus type 1 polypeptide in trigeminal ganglia from latently infected animals. Infect. Immun. 34:987-992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halford, W. P., B. M. Gebhardt, and D. J. Carr. 1996. Persistent cytokine expression in trigeminal ganglion latently infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Immunol. 157:3542-3549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanke, T., F. L. Graham, K. L. Rosenthal, and D. C. Johnson. 1991. Identification of an immunodominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte recognition site in glycoprotein B of herpes simplex virus by using recombinant adenovirus vectors and synthetic peptides. J. Virol. 65:1177-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawke, S., P. G. Stevenson, S. Freeman, and C. R. Bangham. 1998. Long-term persistence of activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes after viral infection of the central nervous system. J. Exp. Med. 187:1575-1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hickey, W. F., B. L. Hsu, and H. Kimura. 1991. T-lymphocyte entry into the central nervous system. J. Neurosci. Res. 28:254-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hogquist, K. A., S. C. Jameson, W. R. Heath, J. L. Howard, M. J. Bevan, and F. R. Carbone. 1994. T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell 76:17-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irani, D. N., and D. E. Griffin. 1996. Regulation of lymphocyte homing into the brain during viral encephalitis at various stages of infection. J. Immunol. 156:3850-3857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khanna, K. M., R. H. Bonneau, P. R. Kinchington, and R. L. Hendricks. 2003. Herpes simplex virus-specific memory CD8+ T cells are selectively activated and retained in latently infected sensory ganglia. Immunity 18:593-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khanna, K. M., A. J. Lepisto, V. Decman, and R. L. Hendricks. 2004. Immune control of herpes simplex virus during latency. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 16:463-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khanna, K. M., A. J. Lepisto, and R. L. Hendricks. 2004. Immunity to latent viral infection: many skirmishes but few fatalities. Trends Immunol. 25:230-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kramer, M. F., and D. M. Coen. 1995. Quantification of transcripts from the ICP4 and thymidine kinase genes in mouse ganglia latently infected with herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 69:1389-1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lang, A., and J. Nikolich-Zugich. 2005. Development and migration of protective CD8+ T cells into the nervous system following ocular herpes simplex virus-1 infection. J. Immunol. 174:2919-2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu, T., K. M. Khanna, X. Chen, D. J. Fink, and R. L. Hendricks. 2000. CD8+ T cells can block herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) reactivation from latency in sensory neurons. J Exp. Med. 191:1459-1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu, T., Q. Tang, and R. L. Hendricks. 1996. Inflammatory infiltration of the trigeminal ganglion after herpes simplex virus type 1 corneal infection. J. Virol. 70:264-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marten, N. W., S. A. Stohlman, R. D. Atkinson, D. R. Hinton, J. O. Fleming, and C. C. Bergmann. 2000. Contributions of CD8+ T cells and viral spread to demyelinating disease. J. Immunol. 164:4080-4088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marten, N. W., S. A. Stohlman, and C. C. Bergmann. 2000. Role of viral persistence in retaining CD8+ T cells within the central nervous system. J. Virol. 74:7903-7910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masopust, D., and L. Lefrancois. 2003. CD8 T-cell memory: the other half of the story. Microbes Infect. 5:221-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masopust, D., V. Vezys, A. L. Marzo, and L. Lefrancois. 2001. Preferential localization of effector memory cells in nonlymphoid tissue. Science 291:2413-2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mehta, A., J. Maggioncalda, O. Bagasra, S. Thikkavarapu, P. Saikumari, T. Valyi-Nagy, N. W. Fraser, and T. M. Block. 1995. In situ DNA PCR and RNA hybridization detection of herpes simplex virus sequences in trigeminal ganglia of latently infected mice. Virology 206:633-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milligan, G. N., D. I. Bernstein, and N. Bourne. 1998. T lymphocytes are required for protection of the vaginal mucosae and sensory ganglia of immune mice against reinfection with herpes simplex virus type 2. J. Immunol. 160:6093-6100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mueller, S. N., W. Heath, J. D. McLain, F. R. Carbone, and C. M. Jones. 2002. Characterization of two TCR transgenic mouse lines specific for herpes simplex virus. Immunol. Cell Biol. 80:156-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nathenson, S. G., J. Geliebter, G. M. Pfaffenbach, and R. A. Zeff. 1986. Murine major histocompatibility complex class-I mutants: molecular analysis and structure-function implications. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 4:471-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pereira, R. A., and A. Simmons. 1999. Cell surface expression of H2 antigens on primary sensory neurons in response to acute but not latent herpes simplex virus infection in vivo. J. Virol. 73:6484-6489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perng, G. C., C. Jones, J. Ciacci-Zanella, M. Stone, G. Henderson, A. Yukht, S. M. Slanina, F. M. Hofman, H. Ghiasi, A. B. Nesburn, and S. L. Wechsler. 2000. Virus-induced neuronal apoptosis blocked by the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript. Science 287:1500-1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramakrishnan, R., M. Levine, and D. J. Fink. 1994. PCR-based analysis of herpes simplex virus type 1 latency in the rat trigeminal ganglion established with a ribonucleotide reductase-deficient mutant. J. Virol. 68:7083-7091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sallusto, F., D. Lenig, R. Forster, M. Lipp, and A. Lanzavecchia. 1999. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature 401:708-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimeld, C., J. L. Whiteland, S. M. Nicholls, E. Grinfeld, D. L. Easty, H. Gao, and T. J. Hill. 1995. Immune cell infiltration and persistence in the mouse trigeminal ganglion after infection of the cornea with herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Neuroimmunol. 61:7-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simmons, A., and D. C. Tscharke. 1992. Anti-CD8 impairs clearance of herpes simplex virus from the nervous system: implications for the fate of virally infected neurons. J. Exp. Med. 175:1337-1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith, C. M., G. T. Belz, N. S. Wilson, J. A. Villadangos, K. Shortman, F. R. Carbone, and W. R. Heath. 2003. Cutting edge: conventional CD8α+ dendritic cells are preferentially involved in CTL priming after footpad infection with herpes simplex virus-1. J. Immunol. 170:4437-4440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spivack, J. G., and N. W. Fraser. 1987. Detection of herpes simplex virus type 1 transcripts during latent infection in mice. J. Virol. 61:3841-3847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steiner, I., N. Mador, I. Reibstein, J. G. Spivack, and N. W. Fraser. 1994. Herpes simplex virus type 1 gene expression and reactivation of latent infection in the central nervous system. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 20:253-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sun, S., X. Zhang, D. F. Tough, and J. Sprent. 1998. Type I interferon-mediated stimulation of T cells by CpG DNA. J. Exp. Med. 188:2335-2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Theil, D., T. Derfuss, I. Paripovic, S. Herberger, E. Meinl, O. Schueler, M. Strupp, V. Arbusow, and T. Brandt. 2003. Latent herpesvirus infection in human trigeminal ganglia causes chronic immune response. Am. J. Pathol. 163:2179-2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Topham, D. J., M. R. Castrucci, F. S. Wingo, G. T. Belz, and P. C. Doherty. 2001. The role of antigen in the localization of naive, acutely activated, and memory CD8+ T cells to the lung during influenza pneumonia. J. Immunol. 167:6983-6990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Turner, S. J., S. C. Jameson, and F. R. Carbone. 1997. Functional mapping of the orientation for TCR recognition of an H2-Kb-restricted ovalbumin peptide suggests that the β-chain subunit can dominate the determination of peptide side chain specificity. J. Immunol. 159:2312-2317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van der Most, R. G., K. Murali-Krishna, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Prolonged presence of effector-memory CD8 T cells in the central nervous system after dengue virus encephalitis. Int. Immunol. 15:119-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Lint, A., M. Ayers, A. G. Brooks, R. M. Coles, W. R. Heath, and F. R. Carbone. 2004. Herpes simplex virus-specific CD8+ T cells can clear established lytic infections from skin and nerves and can partially limit the early spread of virus after cutaneous inoculation. J. Immunol. 172:392-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wallace, M. E., R. Keating, W. R. Heath, and F. R. Carbone. 1999. The cytotoxic T-cell response to herpes simplex virus type 1 infection of C57BL/6 mice is almost entirely directed against a single immunodominant determinant. J. Virol. 73:7619-7626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wherry, E. J., V. Teichgraber, T. C. Becker, D. Masopust, S. M. Kaech, R. Antia, U. H. von Andrian, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Lineage relationship and protective immunity of memory CD8 T cell subsets. Nat. Immunol. 4:225-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wolint, P., M. R. Betts, R. A. Koup, and A. Oxenius. 2004. Immediate cytotoxicity but not degranulation distinguishes effector and memory subsets of CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 199:925-936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yokoyama, W. M., F. Koning, P. J. Kehn, G. M. Pereira, G. Stingl, J. E. Coligan, and E. M. Shevach. 1988. Characterization of a cell surface-expressed disulfide-linked dimer involved in murine T cell activation. J. Immunol. 141:369-376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]