Abstract

The existence of airborne mycotoxins in mold-contaminated buildings has long been hypothesized to be a potential occupant health risk. However, little work has been done to demonstrate the presence of these compounds in such environments. The presence of airborne macrocyclic trichothecene mycotoxins in indoor environments with known Stachybotrys chartarum contamination was therefore investigated. In seven buildings, air was collected using a high-volume liquid impaction bioaerosol sampler (SpinCon PAS 450-10) under static or disturbed conditions. An additional building was sampled using an Andersen GPS-1 PUF sampler modified to separate and collect particulates smaller than conidia. Four control buildings (i.e., no detectable S. chartarum growth or history of water damage) and outdoor air were also tested. Samples were analyzed using a macrocyclic trichothecene-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). ELISA specificity was tested using phosphate-buffered saline extracts of the fungal genera Aspergillus, Chaetomium, Cladosporium, Fusarium, Memnoniella, Penicillium, Rhizopus, and Trichoderma, five Stachybotrys strains, and the indoor air allergens Can f 1, Der p 1, and Fel d 1. For test buildings, the results showed that detectable toxin concentrations increased with the sampling time and short periods of air disturbance. Trichothecene values ranged from <10 to >1,300 pg/m3 of sampled air. The control environments demonstrated statistically significantly (P < 0.001) lower levels of airborne trichothecenes. ELISA specificity experiments demonstrated a high specificity for the trichothecene-producing strain of S. chartarum. Our data indicate that airborne macrocyclic trichothecenes can exist in Stachybotrys-contaminated buildings, and this should be taken into consideration in future indoor air quality investigations.

For the past 25 years, there has been growing concern about the presence of fungi and their adverse human health effects in indoor environments. Several genera of fungi, including Stachybotrys, Chaetomium, and Aspergillus, have raised particular concern because of their associated toxin production. To date, the majority of indoor air quality investigations have focused on analyses of mold growth on building materials (1, 18, 35, 40) and measurements of airborne particulate matter, including dust, fungal conidia (6, 20), and animal danders (13). These types of investigations cannot directly assess occupant exposure to mycotoxins. Exposure to these factors can influence allergic hypersensitivity responses (2, 9, 29) and symptoms of asthma in certain individuals (11, 30) but most likely does not account for often-reported symptoms such as nausea, dizziness, nose bleeds, physical and mental fatigue, and neurological disorders (28, 39) seen in subjects occupying sick buildings.

Among the many fungi isolated from contaminated indoor environments, Stachybotrys chartarum is one of the most well known. S. chartarum is a known producer of a number of potent mycotoxins, in particular the macrocyclic trichothecenes verrucarins B and J, roridin E, satratoxins F, G, and H, and isosatratoxins F, G, and H (23, 26). It has been proposed to be associated with adverse human health effects (8, 12, 14, 24, 25). The members of the macrocyclic trichothecene family of mycotoxins are known to be potent inhibitors of protein synthesis in eukaryotes (15, 38, 48). Goodwin et al. (16) and Murphy et al. (33) showed that when the nonmacrocyclic trichothecene mycotoxin diacetoxyscirpenol (also known as anguidine) was injected into human beings, the observed symptoms were nausea, vomiting, low blood pressure, drowsiness, ataxia, and mental confusion.

S. chartarum airborne mycotoxins have been studied in various laboratory settings (4, 34, 44, 47) and are known to be detrimental in several animal models (32, 37, 49). However, research that effectively demonstrates the presence of airborne S. chartarum trichothecene mycotoxins in native indoor environments is lacking. Studies have mostly focused on detecting these mycotoxins on bulk material (47) or in settled dust (43). The aim of this study was to determine if airborne macrocyclic trichothecene mycotoxins exist in indoor environments contaminated with Stachybotrys chartarum, with an emphasis on the development of simple and rapid collection/detection techniques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Indoor environments. (i) Test environments.

Eight mold-contaminated buildings encompassing 16 tested rooms and 40 air collections throughout the state of Texas were chosen for sampling. These were labeled test buildings 1 to 8. The buildings ranged in age from 10 years (buildings 1 to 3) to >20 years old (buildings 4 to 8). Total visible fungal growth and water damage ranged from <1 ft2 to >500 ft2. Further fungal growth was noted upon invasive inspection (i.e., hidden mold contamination). Prior to air sampling, fungi growing on visible surfaces were sampled using the adhesive tape technique (45). Microscopic identification was based on morphology and was performed by a trained technician in our laboratory. Rooms chosen for testing demonstrated the highest degree of visible fungal contamination and/or water damage present in the building. Buildings 1, 2, 7, and 8 were unoccupied. For the remaining buildings, occupants were instructed not to enter or disturb the test rooms during sampling. To prevent cross-contamination, sampled rooms were isolated from the rest of the building by shutting doors, or in cases of heavy contamination, were sealed with plastic sheeting and duct tape. A basic description of each test building is outlined in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Test building descriptions

| Building no. | Occupancy | Agea (yrs) | No. of rooms/no. of samples taken | Visible water damageb (ft2) | Total visible fungal contaminationc (ft2) | Identified fungal generad |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Empty | 10 | 3/11 | 200-300 | 50-100 | Stachybotrys, Chaetomium, Memnoniella, Nigrospora, Cladosporium |

| 2 | Empty | 10 | 2/7 | >500 | >500 | Stachybotrys, Aspergillus, Cladosporium, Penicillium, Alternaria, Chaetomium |

| 3 | Occupied | 10 | 1/4 | 1-10 | 10-20 | Chaetomium, Stachybotrys |

| 4 | Occupied | >20 | 1/1 | 1-10 | <10 | Stachybotrys |

| 5 | Occupied | >20 | 2/2 | 50-100 | 50-100 | Stachybotrys, Cladosporium, Aspergillus |

| 6 | Occupied | >20 | 2/4 | 100-200 | 20-50 | Chaetomium, Aspergillus |

| 7 | Empty | >20 | 4/8 | >500 | 200-300 | Memnoniella, Alternaria, Cladosporium, Aspergillus, Fusarium |

| 8 | Empty | >20 | 1/3 | 100-200 | 100-200 | Aspergillus, Alternaria, Stachybotrys, Penicillium, Fusarium, Chaetomium |

Approximate age during the time of sampling.

This estimate includes growth that was observed following invasive inspection.

Visible surface growth only. Assessment was made using the adhesive tape technique as described in the text.

Fungi are listed in order of prevalence (highest to lowest).

(ii) Control environments.

Four buildings (no visible fungal contamination or history of water incursion events) encompassing 14 tested rooms and 30 air collections in West Texas were chosen for control sampling. These were labeled control buildings 1 to 4. Building 2 was <10 years old, while buildings 1, 3, and 4 were >20 years old. Sampled rooms were randomly chosen. All buildings were occupied. Occupants were instructed not to enter or disturb the rooms during sampling. To prevent cross-contamination, sampled rooms were isolated by shutting the entry doors.

Air sampling. (i) Air samplers.

Two samplers were employed for the collection of airborne trichothecene mycotoxins, namely, a SpinCon PAS 450-10 bioaerosol sampler (Sceptor Industries, Inc., Kansas City, MO) and an Andersen GPS-1 polyurethane foam (PUF) high-volume air sampler (Thermo Electron Corporation, Cheswick, PA). The SpinCon sampler has been evaluated in the outdoor environment and has been determined to be a highly effective air sampling device (3, 5). From October 2001 to September 2002, the SpinCon sampler was employed for the collection of airborne Bacillus anthracis in buildings throughout the Washington, D.C., area following the well-known bioterrorism attack on that area (21). For our purposes, the machine was operated at a manufacturer-set flow rate of 450 liters per min (lpm). Entrained solids were collected and concentrated in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution (pH 7.4) to a final volume of 10 ml. Over the collection period, evaporated PBS was replaced by water in a standardized manner.

High-volume samplers incorporating polyurethane foam are generally designed for the collection of airborne pesticides and organic pollutants in the outdoor environment (27, 31, 42). To our knowledge, the Andersen PUF sampler has never been used for indoor air applications. For our purposes, the apparatus was modified to separate and collect particulates smaller than S. chartarum conidia through the incorporation of two sterile glass fiber filters of decreasing pore sizes placed in a series (Fig. 1). We have been able to show, using a similar filtration setup in a controlled setting, that conidia can be separated from minute particles that carry trichothecene mycotoxins (4). Large particles were captured using a 90-mm GF/D glass fiber filter (Whatman, Clifton, NJ) with a pore size of 2.7 μm in the upper chamber of the sampling module. Air leaks were prevented by using custom-made rubber gaskets (85- and 110-mm inner and outer diameters, respectively). To collect remaining particulate matter, a 90-mm Whatman EPM-2000 glass microfiber filter was fit immediately before the lower chamber of the sampling module. EPM filter material was selected by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as the standard for use in high-volume air sampling. According to the manufacturer, this material is 99.99% efficient for 0.3-μm dioctyl phthalate particles (standard particles for testing filter efficiencies) at a 5-cm/s flow rate. A metal screen was placed immediately after the filter to disperse the air pressure and prevent punctures and/or tearing. The machine was adjusted to collect at a flow rate of 150 lpm. The flow rate was based on a calibration curve that was determined with the filters in place using a manometer attached to the sampling module.

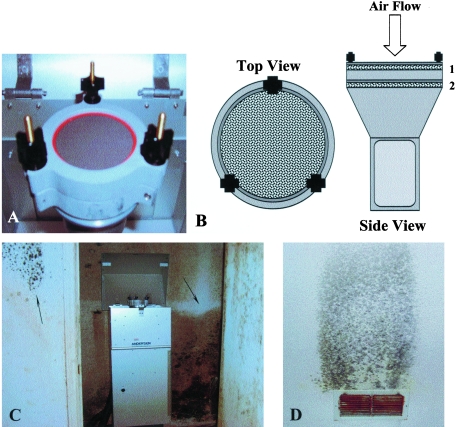

FIG. 1.

Andersen GPS-1 PUF high-volume air sampler setup. Panel A shows the collection module following a 24-hour sampling period. The top filter with a considerable amount of collected particulates is visible here. Panel B is a schematic of the collection module, with a top view on the left and a side view on the right. The module was modified to collect and separate particles using glass microfiber filters. Large particles, including most fungal conidia, were collected on 90-mm-diameter 2.7-μm-pore-size GF/D filters (1), while remaining particles able to pass through the first filter were collected on highly efficient EPM filters of the same diameter (2). A heavily mold-contaminated storage closet adjacent to the source of the water damage in test building 8 (shown in panel C) was chosen for sampling. Water-saturated air and ensuing fungal contamination were a result of major damage to the air-conditioning unit. The degree of the damage was evident by growth near the air exit grates throughout the building (D).

(ii) Controlled SpinCon setup.

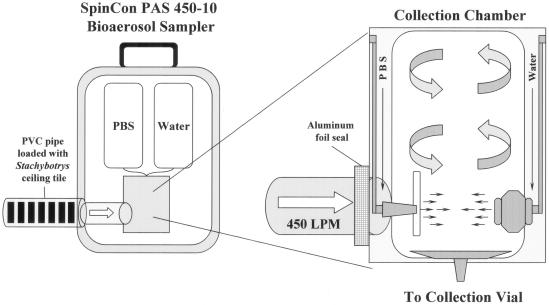

Prior to building sampling, controlled trials were performed to determine if the SpinCon bioaerosol sampler was capable of collecting airborne macrocyclic trichothecene mycotoxins. To do this, we constructed a setup whereby air was pulled over cellulose-containing ceiling tile with confluent S. chartarum growth directly into the collection chamber of the SpinCon sampler (Fig. 2). We have described the conditions and methods for the growth of S. chartarum on ceiling tile previously (4). For sampling, a 24-inch section of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipe filled with S. chartarum-contaminated ceiling tile (representing approximately 500 cm2 of growth) was attached to the air inlet of the SpinCon sampler. Potential leaks surrounding the inlet were covered by securely taping several layers of aluminum foil around the PVC pipe at that vicinity. All controlled trials were run in an outdoor environment. Sampling was performed for 10 and 30 min (n = 3 replicates for each time interval). For comparison purposes, collection was also performed using an equal area of sterile ceiling tile in the same manner. Results from the controlled SpinCon setup are shown in Table 2.

FIG. 2.

SpinCon PAS 450-10 bioaerosol sampler controlled setup. PVC pipe was filled with S. chartarum-contaminated ceiling tile and attached to the air inlet of the SpinCon sampler. Potential leaks surrounding the inlet were sealed with aluminum foil. Air passing over and through the ceiling tiles was directed into the collection chamber at a rate of 450 lpm. Aerosolized Stachybotrys chartarum conidia and other particulate matter were captured by a swirling column of PBS in the collection chamber. These trials were run in an outdoor environment. Sampling was performed for 10 and 30 min (n = 3 replicates for each time interval). For comparison purposes, collection was also performed using an equal area of sterile ceiling tile in the same manner.

TABLE 2.

Air sampling analyses from controlled SpinCon setup

| Sample | Sampling time (min) | Avg % ELISA inhibitiona | Avg trichothecene equivalentsb (ng/ml) | Avg trichothecene equivalents/ m3 of sampled airc (pg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sterile ceiling tile | 10 | 20.8 ± 5.8 | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 62.4 ± 12.8 |

| 30 | 47.4 ± 7.8 | 0.87 ± 0.34 | 64.4 ± 25.1 | |

| Stachybotrys-contaminated ceiling tile | 10 | 76.4 ± 0.6 | 6.7 ± 0.4 | 1.48 × 103 ± 91.3* |

| 30 | 87.6 ± 0.2 | 36.4 ± 1.6 | 2.69 × 103 ± 120* |

Means ± standard deviations of three individual runs. Values are based on that for PBS alone (average of eight separately run samples).

Means ± standard deviations of three individual runs are shown. Values were derived from an ELISA-based macrocyclic trichothecene standard curve.

Means ± standard deviations of three individual runs are shown. Estimated values are based on the average trichothecene equivalents for the entire collected sample, collection time, and flow rate of the SpinCon sampler. For example, a total of 13.5 m3 of air was collected for each 30-minute sample. Given a final working volume of 1 milliliter, trichothecene concentrations were then estimated from values obtained from ELISA testing. *, significantly different (P < 0.05) from sterile ceiling tile sampled in a similar manner.

(iii) Volumetric spore traps.

In each tested environment, airborne conidium counts (based on 5-minute samples) were evaluated prior to and during sampling using either an Allergenco MK-3 nonviable volumetric collector (Allergenco, San Antonio, TX) or a Burkard personal volumetric air sampler (Spiral Biotech, Inc., Norwood, MA). The collection characteristics of the Allergenco and Burkard samplers have been shown to be similar (36). One sample (referred to as a spore trap from here on) was collected per air sampling condition described below. For reference purposes, one spore trap was collected in the outdoor environment just prior to sampling of each building. An outdoor spore trap was not collected for building 7 because wet weather conditions did not allow for proper sampling. For each collection period, the samplers were placed at an elevation of 3 to 4 feet above the ground. Conidia and other airborne particulates were collected on glass microscope slides that had been coated with a thin layer of petroleum grease using a foam makeup applicator. Following sampling, conidia were identified to the genus level by a trained technician in our laboratory using an Olympus BH2-RFCA optical light microscope (Olympus America, Inc., Melville, NY). Airborne conidium concentrations were calculated using the following equation: number of conidia counted/{[conversion number for microscopic field (mm) and trace width (mm)] × [sampling flow rate (m3/min)] × [sampling time (min)]}. The conversion number was defined as the microscope objective diameter divided by the trace width. For our case, this number, for the 400× objective, was set at 0.409 (0.45 mm/1.1 mm). The sampling flow rate for both volumetric spore traps was 0.015 m3/min, and the sampling time was 5 minutes. For simplicity, airborne conidium concentrations were determined by dividing the conidium counts by 0.031. Based on these calculations, the lower limit of detection was set at 1 conidium per collected trace or 32 conidia/m3 of air. In addition to conidium characterization, levels of debris (unidentifiable particles) were qualitatively measured based on the approximate percentage of the viewed field covered by such particles, as follows: very light (<20%), light (21 to 40%), medium (41 to 60%), heavy (61 to 80%), and very heavy (>80%; approaching unreadable). Semiquantification of debris was important because it was composed mostly of highly respirable particles (<2 μm in diameter) and was viewed as a potential source of mycotoxins (i.e., the particles could serve as carriers of macrocyclic trichothecenes).

(iv) Sampling conditions.

The use of personal protective equipment was observed for all test areas. This included impervious full-body suits (Sunrise Industries, Inc., Guntersville, AL), full-face-piece respirators (3M, St. Paul, MN) equipped with organic vapor/acid gas cartridge/P100 filter cartridges (3M 60923), or a combination of the two.

Test buildings 1 to 7 were sampled using the SpinCon PAS 450-10 bioaerosol sampler. Collection was performed at an elevation of 3 to 4 feet above the ground. Air was sampled in each room under static and/or disturbed conditions for 10 min (n = 7 rooms and 9 samples under disturbed conditions), 20 min (n = 4 rooms and 4 samples under disturbed conditions), 30 min (n = 6 rooms and 6 samples under disturbed conditions), and/or 120 min (n = 14 rooms, with 14 samples under static conditions and 4 samples under disturbed conditions). For each room, collection was first performed under static conditions, followed by collection with air disturbance in the order of sampling times (longest to shortest). Following each sampling interval, rooms were left undisturbed for 20 to 30 min to allow the room air to return to precollection conditions. To prevent cross-contamination between samples, the SpinCon sampler was run through a rinse cycle, as instructed by the manufacturer, using a 5% (vol/vol) bleach solution followed by pure water. We have shown that rinsing with a dilute bleach solution is effective for the removal/inactivation of trichothecene mycotoxins (50). For those areas sampled with disturbance, 20-inch box fans (Lasko Products, Inc., West Chester, PA) set on “high” were placed in a manner that would circulate the air in the room (one in each corner of the room). The fans were allowed to run for 5 minutes prior to sample collection for the initial generation of particulate matter. One 5-minute volumetric spore trap was obtained for each test as already described. For static conditions, these samples were taken just prior to sampling. For disturbed conditions, the spore traps were collected 5 minutes prior to the end of collection. In addition, control buildings 1 to 4 were sampled in a similar manner under static and/or disturbed conditions for 10 min (n = 6 rooms and 6 samples under disturbed conditions) and 120 min (n = 14 rooms and 24 samples under static conditions). For reference, four outdoor air samples were collected using the SpinCon sampler for 30, 60, 90, and 120 min (n = 1 for each sampling period). Spore traps for these outdoor samples were taken just prior to sampling for the sole purpose of determining if S. chartarum conidia were present.

Test building 8 was sampled using an Andersen GPS-1 PUF high-volume air sampler modified as already described. The sampling inlet was at the manufacturer-set height of approximately 5 feet. Air was sampled in a heavily mold-contaminated closet (Fig. 1) under static conditions for 24, 48, and 72 h (n = 1 for each time period). A 5-minute Allergenco spore trap was taken prior to each sampling interval. In addition, one room in a control building was sampled for 24 h under static conditions. Volumetric spore traps were collected for each control area as described for test buildings.

Sample preparation.

Following collection, SpinCon samples (all 10 ml) were filtered using Fisher 13-mm-diameter nylon syringe filters with a 0.45-μm pore size (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). The loss of sample due to filter absorbance was minimal. The filtered fluid was sterilely transferred to 15-ml polypropylene conical centrifuge tubes, frozen at −80°C, and lyophilized using a VirTis Freezmobile (SP Industries, Inc., Gardiner, NY). The dried samples were individually resuspended in 1 ml of room-temperature (25°C) pyrogen-free water for immediate testing.

Filters obtained from the Andersen PUF sampler were removed immediately after testing and transferred individually to 50-ml polypropylene centrifuge tubes on-site. The filters were suspended in 40 ml of PBS, vortexed vigorously for 60 seconds, removed from the tubes using sterile forceps, and then discarded. The PBS extracts were filtered (as described above) into new 50-ml tubes. These were frozen at −80°C, lyophilized, and resuspended in 1 ml pyrogen-free water for immediate testing.

Macrocyclic trichothecene analysis.

Samples were analyzed for macrocyclic trichothecenes using a QuantiTox kit for trichothecenes (EnviroLogix, Portland, ME) as outlined by the manufacturer. This competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit incorporates trichothecene-specific antibodies immobilized in polystyrene microtiter wells (7). We have previously demonstrated that this assay is highly specific for macrocyclic trichothecene mycotoxins, particularly those produced by Stachybotrys chartarum (4). All reagents and antibody-coated wells were allowed to equilibrate to room temperature before use. For testing, samples or control mixtures were added to wells in triplicate. Following incubation, wells were read at 450 nm using an EL-312 microtiter plate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT). To ensure that the ELISA ran correctly, the macrocyclic trichothecene roridin A was used at a concentration of 50 ng/ml in PBS as a positive control for each set of tests. PBS alone was used as a negative control.

Fungal conidia and indoor allergen cross-reactivity.

The composition of indoor air is complex in that numerous types of particulates (fungal conidia, bacteria, animal dander, etc.) are present at any given time. Because of this, we tested our detection method (ELISA) against some of the most common indoor air constituents. The following 14 strains of fungi were tested: one macrocyclic trichothecene-producing Stachybotrys chartarum strain (ATCC 201212), four atranone-producing Stachybotrys chartarum strains (IBT 9633, IBT 9757, IBT 9293, and IBT 9290; IBT Culture Collection of Fungi, Mycology Group, BioCentrum DTU, Technical University of Denmark), Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus niger (ATCC 10575), Chaetomium globosum (ATCC 16021), Cladosporium cladosporioides, Fusarium sporotrichioides (ATCC 24630), Memnoniella echinata (ATCC 11973), Penicillium chrysogenum, Trichoderma viride, and one species of Rhizopus. Of the five S. chartarum strains tested, only strain 201212 produced macrocyclic trichothecenes (26). Fungi not purchased from a supplier were collected from outside samples, purified, and identified in our laboratory by a trained technician according to the methods of Sutton et al. (46) and de Hoog et al. (10). All fungi were maintained on potato dextrose agar (BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD) in 90-mm plastic petri dishes in a controlled 25°C incubator (Fisher Scientific Isotemp incubator; model 304).

For testing purposes, conidia were collected from plates that had reached confluence (approximately 7 to 14 days), using sterile cotton swabs. To collect the conidia, swabs were gently rolled over the surface of the fungal growth. The amount of culture swabbed was variable, as certain fungi do not sporulate as readily as others (e.g., Alternaria versus Aspergillus). The cotton tips of the swabs were placed in 1 ml of sterile room-temperature (25°C) PBS in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes and vortexed for approximately 1 minute to remove conidia. The conidia were then counted using a hemacytometer and diluted in PBS (pH 7.4) to concentrations that were based on what we observed in sampled buildings (Table 3). For example, the highest concentration of Cladosporium conidia collected in any given test building was approximately 1.2 × 106 total conidia (1,871 conidia/m3 of sampled air collected at 150 lpm for 72 h). Other dilutions were as follows: 5 × 105 for S. chartarum 201212, 7 × 105 for A. alternata, 4.7 × 106 for A. niger, 1.6 × 106 for C. globosum, 7 × 105 for M. echinata, and 4.7 × 106 for P. chrysogenum. Fungi that were in low abundance (<1 × 104 total collected conidia) in the indoor environments were tested at 106, 105, and 104 conidia/ml. These included F. sporotrichioides, Rhizopus spp., and Trichoderma spp. Similarly, the atranone-producing strains of Stachybotrys were diluted to 1 × 106 conidia/ml. Two 10-fold dilutions were made in PBS (pH 7.4) from these suspensions, resulting in three test concentrations for each organism.

TABLE 3.

Airborne conidium types and counts isolated from outdoor air and test buildings for each sampling time and condition

| Test build- inga | Roomb | Sampling time (min), conditionsc | Airborne fungal genus (conidium count per m3 of air)d

|

Debris counte | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alt | Asco | Bip | Clado | Curv | Fus | Memn | Nigro | Pen/Asp | Stachy | ||||

| 1 | ODA | NA | 774 | 1,065 | <LDL | 2,548 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 65 | 12,226 | <LDL | Medium |

| Kitchen | 120, static | 32 | 5 | <LDL | 1,645 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 11,226 | <LDL | Very light | |

| 30, disturbed | 3,710 | 32 | <LDL | 161 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 3,710 | <LDL | Very light | ||

| 10, disturbed | 97 | 581 | <LDL | 1,355 | <LDL | 161 | <LDL | <LDL | 10,677 | 452 | Medium | ||

| TV room | 120, static | 548 | 1,484 | <LDL | 1,548 | 65 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 48,613 | 1,226 | Heavy | |

| 120, disturbed | 323 | 4,065 | <LDL | 1,000 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 65 | 17,129 | 5,032 | Medium | ||

| 30, disturbed | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 97 | <LDL | 32 | <LDL | 32 | 3,935 | <LDL | Very light | ||

| 10, disturbed | 161 | 2,452 | <LDL | 710 | <LDL | 226 | <LDL | <LDL | 28,290 | 2,710 | Medium | ||

| Bedroom | 120, static | 258 | 1,161 | <LDL | 161 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 9,419 | <LDL | Medium | |

| 120, disturbed | 226 | 3,355 | <LDL | 1,323 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 32 | 3,968 | <LDL | Medium | ||

| 30, disturbed | 258 | 806 | <LDL | 1,065 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 6,065 | <LDL | Light | ||

| 10, disturbed | 355 | 5,677 | <LDL | 2,355 | 97 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 7,935 | <LDL | Medium | ||

| 2 | ODA | NA | 129 | 258 | <LDL | 355 | 194 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 3,161 | <LDL | Medium |

| Main entry | 120, static | 226 | 1,548 | <LDL | 1,000 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 32 | 5,806 | 1,161 | Heavy | |

| 120, disturbed | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | THTC | ||

| 30, disturbed | 129 | 613 | <LDL | 1,387 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 65 | 6,581 | 323 | Medium | ||

| 10, disturbed | 65 | 710 | <LDL | 1,065 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 5,839 | 226 | Heavy | ||

| Kitchen | 120, static | 226 | 774 | <LDL | 194 | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 2,387 | 3,097 | Heavy | |

| 120, disturbed | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | THTC | ||

| 30, disturbed | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | THTC | ||

| 3 | ODA | NA | 677 | 871 | <LDL | 3,129 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 32 | 3,226 | <LDL | Light |

| Laundry room | 120, static | 194 | 129 | <LDL | 65 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 4,032 | 8,839 | Medium | |

| 10, Agg 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 16,968 | Very heavy | ||

| 10, Agg 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 14,355 | Very heavy | ||

| 10, Agg 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | THTC | ||

| 4 | ODA | NA | 454 | 194 | 65 | 1,452 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 1,871 | <LDL | Light |

| Living room | 30, Agg | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | THTC | |

| 5 | ODA | NA | 97 | 129 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 355 | <LDL | Very light |

| Front bathroom | 120, Static | 32 | 32 | <LDL | 323 | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 1,129 | <LDL | Light | |

| Back bathroom | 120, static | 65 | 548 | <LDL | 65 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 355 | <LDL | Light | |

| 6 | ODA | NA | 129 | 97 | <LDL | 1,710 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 32 | 1,645 | <LDL | Light |

| Kitchen | 120, static | <LDL | 32 | <LDL | 226 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 1,581 | <LDL | Light | |

| 10, disturbed | <LDL | 419 | <LDL | 129 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 2,548 | 32 | Light | ||

| Garage | 120, static | <LDL | 161 | <LDL | 419 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 4,677 | <LDL | Medium | |

| 10, disturbed | 65 | 516 | <LDL | 1,065 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 10,871 | <LDL | Medium | ||

| 7 | Hall 1 | 120, static | <LDL | 32 | <LDL | 97 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 1,516 | <LDL | Light |

| 20, disturbed | <LDL | 452 | <LDL | 161 | <LDL | <LDL | 4,387 | <LDL | 3,548 | <LDL | Medium | ||

| Hall 2 | 120, static | 32 | 65 | <LDL | 65 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 2,774 | <LDL | Light | |

| 20, disturbed | <LDL | 65 | <LDL | 258 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 13,806 | <LDL | Light | ||

| Room 253 | 120, static | <LDL | 11,387 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 12,839 | <LDL | 1,258 | <LDL | Light | |

| 20, disturbed | <LDL | 6,387 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 18,323 | <LDL | 2,226 | <LDL | Heavy | ||

| Room 259 | 120, static | 97 | 65 | <LDL | 129 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 2,065 | <LDL | Light | |

| 20, disturbed | <LDL | 65 | <LDL | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 6,935 | <LDL | Medium | ||

| 8 | ODA | NA | 355 | 258 | <LDL | 1,258 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 2,548 | <LDL | Light |

| Closet | 24 h, static | 32 | 129 | <LDL | 1,387 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 1,867 | <LDL | Light | |

| 48 h, static | 161 | 3,710 | <LDL | 807 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 10,774 | <LDL | Light | ||

| 72 h, static | 32 | 129 | <LDL | 1,871 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 1,677 | <LDL | Light | ||

Buildings 1 to 7 were sampled with the SpinCon PAS 450-10 bioaerosol sampler. Building 8 was sampled with the Andersen GPS-1 PUF high-volume air sampler modified as described in the text.

Outdoor air (ODA) was considered normal and served as a control for sampling. An outdoor air sample was not available for building 7 because wet weather conditions did not allow for the collection of a sample.

Rooms were sampled under static and/or disturbed conditions for the noted times. Air disturbance was accomplished using 20-inch box fans on a “high” setting. Disturbance was allowed for 5 minutes prior to starting the SpinCon collection. Agg, collections taken during aggresive sampling; NA, not applicable.

Five-minute volumetric spore traps were taken to assess airborne fungal conidium types and concentrations as well as to qualify the amount of debris present. Calculations are described in the text. Building 5 was sampled using a Burkard personal volumetric air sampler. All other buildings were tested using an Allergenco MK-3 nonviable volumetric collector. For static conditions, samples were taken just prior to collection. For disturbed conditions, spore traps were started 5 minutes prior to the end of the sampling period. Key: Alt, Alternaria; Asco, ascospores (most likely Chaetomium, but we were unable to confirm); Bip, Bipolaris; Clado, Cladosporium; Curv, Curvularia; Fus, Fusarium; Memn, Memnoniella; Nigro, Nigrospora; Pen/Asp, Penicillium/Aspergillus-like (unable to confirm); Stachy, Stachybotrys; NA, not applicable as debris counts were too high; <LDL, less than the lower detection limit of 32 conidia/m3 of air.

Debris was defined as unidentifiable particles and was qualified based on the approximate percentage of the viewed field covered by such particles, as follows: very light (<20%), light (21 to 40%), medium (41 to 60%), heavy (61 to 80%), and very heavy (>80%). THTC, too heavy to count.

For ELISA testing, the fungal spore suspensions were centrifuged at 14,500 rpm for 1 min to pellet the conidia. Care was taken not to disturb the conidium pellet, and only the top 80% of the supernatant was used for ELISA testing. Each sample was run in duplicate wells on two separate occasions.

The following three common indoor allergens (Indoor Biotechnologies, Charlottesville, VA) were also tested: Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus allergen 1 (dust mite allergen; Der p 1), Felis domesticus allergen 1 (cat hair extract; Fel d 1), and Canis familiaris allergen 1 (dog hair extract; Can f 1). Allergens were received in 50% glycerol, and for ELISA testing purposes, they were individually diluted in PBS to 50 ng/ml, 5 ng/ml, and 500 pg/ml. Samples were tested in triplicate wells.

ELISA interpretation.

ELISA results for building samples were converted into percentages of inhibition and relative trichothecene concentrations based on the raw data (absorbance readings at 450 nm). The percentages of inhibition represent the degrees of inhibition the test samples had on the capability of the satratoxin G-horseradish peroxidase conjugate to bind to the immobilized antibody. They were calculated as done by Schick et al. (41), using the following equation: % inhibition = 100 × 1 − [(optical density at 450 nm of sample − background)/(optical density at 450 nm of control − background)]. A higher percent inhibition corresponds to a greater concentration of trichothecenes in the sample.

To obtain relative trichothecene concentrations, an ELISA-based macrocyclic trichothecene standard curve was developed and previously described by our laboratory (4). Briefly, a mixture of four macrocyclic trichothecenes (satratoxins G and H, roridin A, and verrucarin A) in equal amounts was diluted to 12 test concentrations (500 to 0.1 ng/ml) and tested via ELISA as already described. Satratoxins G and H were purified in our laboratory as described by Hinkley and Jarvis (23). Roridin A and verrucarin A were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO). Average ELISA absorbance readings at 450 nm were plotted against toxin concentrations (n = 3 replicates per concentration) to generate a standard curve. Using this curve, an approximate trichothecene amount was determined for each sample (in ng/ml). Taking into account the collection rate of the air samplers and assuming 100% air sampling efficiency, a semiquantitative estimate of the amount of airborne trichothecenes for each tested area was then determined (in pg/m3). Cross-reactivities to fungal extracts and allergens were expressed only as percentages of inhibition.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using Sigma Stat 2.0 software (Systat Software, Inc., Point Richmond, CA). Controls were grouped based on the sampling time. Test samples were individually compared to control groups (e.g., each 120-minute static test was compared to the 120-minute static control group) by Student's t test. Statistical significance was defined as having a P value of <0.05. All conditions of normality were met for these analyses. Because 20-, 30-, and 120-min disturbed sampling was not performed in control environments, these samples were compared to environments sampled for 120 min under static conditions.

Additionally, test samples were grouped and compared to control groups. Test buildings where Stachybotrys chartarum was not clearly identified using our survey methods were excluded from statistical analyses because they were not applicable for trichothecene determination. These included five rooms (all rooms in building 7 and the upstairs bedroom in building 1). Thirty-minute samples (n = 15 data points) and 2-hour samples (n = 27 data points under static conditions and 9 data points under disturbed conditions) were compared to 2-hour static controls (n = 69 data points) using a Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on ranks. Ten-minute test samples taken under disturbed conditions (n = 24 data points) were compared to similarly sampled controls (n = 9 data points) using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Statistical significance for these analyses was reported for P values of < 0.001.

Data obtained from samples collected by the Andersen PUF sampler (n = 3 data points for each filter type and collection period) were normalized and compared using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc analysis. Test filters were compared to corresponding filter types that were used for 24-hour sampling in a control environment. Statistical significance was defined as having a P value of <0.05.

All ELISA cross-reactivities (as percentages of inhibition) for fungal extracts and allergens were compared to PBS alone using a one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

Airborne conidium types and counts.

Airborne conidium types and concentrations for test and control buildings are shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Marked differences were seen between buildings, individual rooms within the same building, sampling times, and disturbance conditions. Overall airborne conidium types and counts were higher in test buildings than in control buildings. In control buildings and outdoor environments, airborne conidium types and counts, in a generalized order of prevalence, were as follows: Penicillium/Aspergillus-like, Cladosporium, Alternaria, ascospores (likely Chaetomium, but unable to confirm due to the absence of fruiting bodies), Bipolaris, Nigrospora, and Curvularia. Fusarium, Memnoniella, and Stachybotrys conidia were not isolated from these environments. In test buildings, airborne conidium types and counts, in order of prevalence, were as follows: Penicillium/Aspergillus-like, ascospores, Cladosporium, Alternaria, Stachybotrys, Memnoniella, Fusarium, Nigrospora, and Curvularia. Bipolaris conidia were not isolated from test buildings. Accurate counts could not be made for buildings 2 to 4 under some of the disturbed sampling conditions/aggressive sampling. This was due to an overwhelming amount of collected debris. However, attempts were made to assess the airborne Stachybotrys conidium concentrations in building 3 during aggressive sampling. Overall, higher airborne conidium counts were observed under static versus disturbed conditions in test and control buildings, although concentrations were higher for shorter periods of disturbance (i.e., 10 and 20 versus 30 and 120 min of sampling). The same trend was seen with debris counts, where static conditions and shorter disturbance intervals resulted in the highest counts.

TABLE 4.

Airborne conidium types and counts isolated from outdoor air and control buildings for each sampling time and condition

| Control buildinga | Roomb | Sampling time (min), conditionsc | Airborne fungal genus (conidium counts per m3 of air)d

|

Debris counte | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alt | Asco | Bip | Clado | Curv | Fus | Memn | Nigro | Pen/Asp | Stachy | ||||

| 1 | ODA | NA | 484 | 194 | 65 | 1,452 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 32 | 1,871 | <LDL | Light |

| Room 1 | 120, static | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | 97 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 226 | <LDL | Light | |

| Room 2 | 120, static | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | Light | |

| Room 3 | 120, static | <LDL | 65 | <LDL | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 32 | 129 | <LDL | Very light | |

| Room 4 | 120, static | <LDL | 65 | <LDL | 129 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 32 | 548 | <LDL | Light | |

| Room 5 | 120, static | <LDL | 32 | <LDL | >LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | >LDL | 161 | <LDL | Very light | |

| 2 | ODA | NA | 194 | 32 | 32 | 1,194 | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | 32 | 1,581 | <LDL | Medium |

| Bedroom | 120, static | 581 | <LDL | 32 | 742 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 1,548 | <LDL | Heavy | |

| Kitchen | 120, static | 194 | <LDL | <LDL | 194 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 1,452 | <LDL | Heavy | |

| Computer room | 120, static | 226 | 32 | <LDL | 323 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 839 | <LDL | Heavy | |

| 3 | ODA | NA | 161 | 97 | <LDL | 1,516 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 65 | 4,129 | <LDL | Medium |

| Computer | 120, static | 32 | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 3,226 | <LDL | Medium | |

| room 1 | 10, disturbed | 32 | 32 | <LDL | 97 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 3,065 | <LDL | Medium | |

| Computer | 120, static | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 3,452 | <LDL | Medium | |

| room 2 | 10, disturbed | 32 | 32 | <LDL | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 1,032 | <LDL | Light | |

| Bedroom | 120, static | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 903 | <LDL | Light | |

| 10, disturbed | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 1,194 | <LDL | Medium | ||

| 4 | ODA | NA | <LDL | 65 | <LDL | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 806 | <LDL | Light |

| Bedroom 1 (trial 1) | 120, static | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | |

| Bedroom 1 | 120, static | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 97 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 3,968 | <LDL | Medium | |

| (trial 2) | 10, disturbed | <LDL | 32 | <LDL | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 806 | <LDL | Light | |

| Bedroom 2 | 120, static | 65 | <LDL | <LDL | 161 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 6,290 | <LDL | Heavy | |

| 10, disturbed | 32 | 32 | <LDL | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 1,645 | <LDL | Medium | ||

| Bedroom 3 | 120, static | 65 | <LDL | <LDL | 97 | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 4,065 | <LDL | Medium | |

| 10, disturbed | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 65 | 32 | <LDL | <LDL | <LDL | 710 | <LDL | Light | ||

Buildings 1 to 4 were sampled with the SpinCon PAS 450-10 bioaerosol sampler. Building 1, room 5, was sampled with the Andersen GPS-1 PUF high-volume air sampler immediately following the SpinCon collection.

Outdoor air (ODA) was considered normal and served as a control for sampling.

Rooms were sampled under static and/or disturbed conditions for the noted times. Air disturbance was accomplished using 20-inch box fans on a “high” setting. Disturbance was allowed for 5 minutes prior to starting the SpinCon collection. NA, not applicable.

Five-minute volumetric spore traps were taken to assess airborne fungal conidium types and concentrations as well as to qualitate the amount of debris present. Calculations are described in the text. All control buildings were tested using an Allergenco MK-3 nonviable volumetric collector. For static conditions, samples were taken just prior to collection. For disturbed conditions, spore traps were started 5 minutes prior to the end of the sampling period. Key: Alt, Alternaria; Asco, ascospores (most likely Chaetomium, but we were unable to confirm); Bip, Bipolaris; Clado, Cladosporium; Curv, Curvularia; Fus, Fusarium; Memn, Memnoniella; Nigro, Nigrospora; Pen/Asp, Penicillium/Aspergillus-like (unable to confirm); Stachy, Stachybotrys; NA, not applicable (overwhelming debris count); NT, not taken; <LDL, less than the lower detection limit of 32 conidia/m3 of air.

Debris was defined as unidentifiable particles and was qualified based on the approximate percentage of the viewed field covered by such particles, as follows: very light (<20%), light (21 to 40%), medium (41 to 60%), heavy (61 to 80%), and very heavy (>80%). NT, not taken.

Controlled SpinCon setup.

Results from the controlled SpinCon setup are shown in Table 2. For reference, the lower limit of ELISA detection for purified samples was 100 pg/ml (4). As can be seen, the collection of airborne trichothecene mycotoxins from Stachybotrys chartarum-contaminated ceiling tile in the sampler was successful. Concentrations were higher after 30 min than after 10 min of sampling (2,700 versus 1,500 picograms/m3 of sampled air). Sterile ceiling tile alone demonstrated ELISA reactivity, but the values were much lower (P < 0.05) than when Stachybotrys was present in the system. Trichothecene values for 10 and 30 min using sterile ceiling tile were 62 and 64 pg/m3 of sampled air, respectively.

Building analyses.

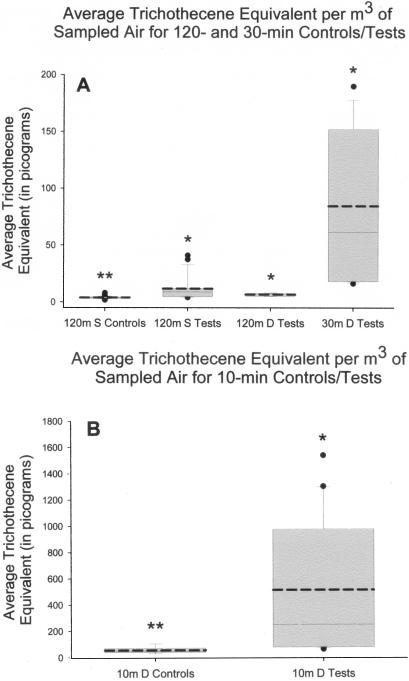

Percentages of inhibition and relative trichothecene concentrations for each SpinCon-sampled test or control room are shown in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. Values were higher with shorter sampling periods and disturbance times, regardless of the nature of the building (test or control). Statistically significant airborne trichothecene equivalents were found in all rooms in buildings 1 to 6 under at least one sampling condition. The values obtained for building 7 were not significantly different from those obtained for control buildings. Estimated airborne trichothecene concentrations in all of the SpinCon-sampled buildings are summarized in Fig. 3. Overall, detectable levels of airborne macrocyclic trichothecene mycotoxins were significantly (P < 0.001) higher in S. chartarum-contaminated buildings than in control buildings. The median values were 3.9, 9.0, 7.5, and 61.5 pg/m3 of air for 2-hour static controls and tests, 2-hour disturbed tests, and 30-minute disturbed tests, respectively. The median values were 44.9 and 248.5 pg/m3 of air for the 10-minute controls and tests, respectively. Outdoor air, regardless of the sampling time, was negative (Table 6). No Stachybotrys conidia were collected in the outdoor air at any of the sampling times (data not shown).

TABLE 5.

Air sampling analyses of SpinCon-sampled Stachybotrys chartarum-contaminated indoor environments

| Test building | Room | Dimensions of room (ft)a | Sampling time (min), conditionsb | Avg % ELISA inhibitionc | Avg trichothecene equivalentsd (ng/ml) | Avg trichothecene equivalents/m3 of sampled aire (pg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Television room | 20 × 25 × 10 | 120, static | 62.5 ± 1.9 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 36.7 ± 4.7* |

| 120, disturbed | 32.4 ± 0.5 | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 7.7 ± 0.2* | |||

| 30, disturbed | 63.5 ± 2.9 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 159 ± 32.1* | |||

| 10, disturbed | 74.2 ± 1.3 | 5.3 ± 0.7 | 1.18 × 103 ± 1.45 × 102* | |||

| 120, static | 21.0 ± 1.9 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 5.2 ± 0.3 | |||

| Bedroom | 20 × 25 × 8 | 120, static | 21.0 ± 1.9 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 5.2 ± 0.3 | |

| 120, disturbed | 10.2 ± 3.5 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | |||

| 30, disturbed | 18.1 ± 2.0 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 18.8 ± 1.3* | |||

| 10, disturbed | 9.0 ± 4.3 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 42.9 ± 5.1 | |||

| 120, static | 17.2 ± 3.0 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | |||

| Kitchen | 25 × 30 × 8 | 120, static | 17.2 ± 3.0 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | |

| 30, disturbed | 17.5 ± 0.6 | 0.25 ± 0.00 | 18.3 ± 0.4* | |||

| 10, disturbed | 30.2 ± 3.0 | 0.39 ± 0.04 | 85.9 ± 9.4 | |||

| 2 | Kitchen | 20 × 20 × 8 | 120, static | 50.8 ± 3.5 | 0.98 ± 0.17 | 18.1 ± 3.2* |

| 120, disturbed | 30.8 ± 3.6 | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 7.4 ± 1.0* | |||

| 30, disturbed | 17.3 ± 4.0 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 18.4 ± 2.4* | |||

| 120, static | 16.8 ± 1.4 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | |||

| Main entry room | 20 × 25 × 8 | 120, static | 16.8 ± 1.4 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | |

| 120, disturbed | 21.4 ± 1.4 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 5.2 ± 0.3 | |||

| 30, disturbed | 49.7 ± 3.8 | 0.93 ± 0.20 | 68.8 ± 14.7* | |||

| 10, disturbed | 50.4 ± 0.6 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 210 ± 7.0* | |||

| 3 | Laundry room | 6 × 8 × 8 | 120, static | 19.0 ± 2.1 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 4.8 ± 0.3 |

| 10, Agg 1 | 95.9 ± 0.4 | Above scale | Above scale* | |||

| 10, Agg 2 | 96.0 ± 0.3 | Above scale | Above scale* | |||

| 10, Agg 3 | 96.1 ± 0.2 | Above scale | Above scale* | |||

| 10, Agg 1 (1:10) | 59.1 ± 3.1 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 355 ± 65.6* | |||

| 10, Agg 2 (1:10) | 69.5 ± 1.5 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 757 ± 99.5* | |||

| 10, Agg 3 (1:10) | 75.7 ± 1.0 | 6.2 ± 0.7 | 1.37 × 103 ± 1.45 × 102* | |||

| 4 | Enclosed living room area | 12 × 4 × 8 | 30, Agg | 63.6 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 158 ± 10.8* |

| 5 | Front bathroom | 10 × 8 × 8 | 120, static | 38.5 ± 2.3 | 0.54 ± 0.05 | 10.0 ± 1.0* |

| Back bathroom | 39.4 ± 0.9 | 0.56 ± 0.02 | 10.3 ± 0.4* | |||

| 6 | Garage | 15 × 25 × 8 | 120, static | 38.3 ± 5.2 | 0.54 ± 0.12 | 10.1 ± 2.1* |

| 10, disturbed | 26.1 ± 1.6 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 73.6 ± 4.1 | |||

| Kitchen | 15 × 20 × 8 | 120, static | 31.4 ± 5.3 | 0.41 ± 0.08 | 7.6 ± 1.4* | |

| 10, disturbed | 24.5 ± 3.4 | 0.32 ± 0.04 | 70.1 ± 8.3 | |||

| 7 | Hall 1 | 8 × 90 × 8 | 120, static | 10.2 ± 2.4 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 3.7 ± 0.3 |

| 20, disturbed | 7.9 ± 3.1 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 20.7 ± 1.9 | |||

| Room 253 | 15 × 15 × 8 | 120, static | 4.3 ± 2.2 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | |

| 20, disturbed | 9.6 ± 2.2 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 21.7 ± 1.4 | |||

| Hall 2 | 8 × 90 × 8 | 120, static | 4.5 ± 4.2 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | |

| 20, disturbed | 6.2 ± 0.9 | 0.18 ± 0.00 | 19.7 ± 0.5 | |||

| Room 259 | 15 × 15 × 8 | 120, static | 15.3 ± 1.5 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | |

| 20, disturbed | 9.7 ± 1.6 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 21.7 ± 1.0 |

Length by width by height.

Rooms were sampled under static and/or disturbed conditions for the noted times. Air disturbance was accomplished using 20-inch box fans on a “high” setting. Disturbance was allowed for 5 minutes prior to starting the SpinCon collection. Buildings 3 and 4 were sampled during aggressive sampling, as noted (Agg).

Data are means±standard deviations. Values are based on that for PBS alone (average of eight separately run samples). Values represent triplicate wells.

Means ± standard deviations are shown. Values were derived from an ELISA-based macrocyclic trichothecene standard curve. Values represent triplicate wells.

Means ± standard deviations are shown. Values represent triplicate wells. Estimated values are based on the average trichothecene equivalents for the entire collected sample, collection time, and flow rate of the SpinCon sampler. For example, a total of 54 m3 of air was collected for each 120-minute sample. Given a final working volume of 1 milliliter, trichothecene concentrations were then estimated from values obtained from ELISA testing. *, values determined to be significantly different (P < 0.05) from those for control environments sampled in a similar manner. Because 20- and 30-minute disturbed sampling was not performed in control environments, these samples were compared to environments sampled for 120 minutes under static conditions.

TABLE 6.

Air sampling analyses of SpinCon-sampled control indoor environments and outdoor air

| Control area | Room | Dimensions of room (ft)a | Sampling time (min), conditionsb | Avg % ELISA inhibitionc | Avg trichothecene equivalentsd (ng/ml) | Avg trichothecene equivalents/m3 of sampled aire (pg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building 1 | Room 1 | 15 × 20 × 10 | 120, static | 21.5 ± 2.6 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 5.3 ± 0.5 |

| Room 2 (trial 1) | 30 × 20 × 10 | 120, static | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | |

| Room 2 (trial 2) | 5.2 ± 3.2 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | |||

| Room 2 (trial 3) | 1.8 ± 3.1 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | |||

| Room 2 (trial 4) | 18.4 ± 2.0 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | |||

| Room 2 (trial 5) | 0.14 ± 0.24 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | |||

| Room 3 | 20 × 20 × 10 | 120, static | 20.0 ± 1.8 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 5.0 ± 0.3 | |

| Room 4 (trial 1) | 20 × 20 × 10 | 120, static | 6.6 ± 4.4 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | |

| Room 4 (trial 2) | 13.9 ± 1.6 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | |||

| Room 4 (trial 3) | 12.9 ± 1.8 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | |||

| Room 4 (trial 4) | 4.6 ± 2.6 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | |||

| Room 4 (trial 5) | 10.8 ± 3.2 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | |||

| Room 4 (trial 6) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | |||

| Room 5 | 25 × 20 × 10 | 120, static | 12.4 ± 1.9 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | |

| Building 2 | Bedroom | 15 × 12 × 8 | 120, static | 11.1 ± 1.8 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 3.8 ± 0.2 |

| Kitchen | 25 × 15 × 10 | 120, static | 17.8 ± 3.3 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | |

| Computer room | 20 × 20 × 8 | 120, static | 13.2 ± 4.7 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | |

| Building 3 | Computer room 1 | 15 × 12 × 8 | 120, static | 17.5 ± 0.5 | 0.25 ± 0.00 | 4.6 ± 0.1 |

| 10, disturbed | 4.3 ± 3.8 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 36.1 ± 6.2 | |||

| Computer room 2 | 15 × 12 × 8 | 120, static | 19.7 ± 12.6 | 0.29 ± 0.13 | 5.4 ± 2.4 | |

| 10, disturbed | 23.8 ± 15.3 | 0.34 ± 0.15 | 75.8 ± 32.8 | |||

| Bedroom | 20 × 20 × 8 | 120, static | 13.1 ± 2.1 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 4.0 ± 0.3 | |

| 10, disturbed | 14.2 ± 3.4 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 49.9 ± 5.2 | |||

| Building 4 | Bedroom 1 (trial 1) | 15 × 15 × 8 | 120, static | 16.3 ± 6.5 | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 4.5 ± 0.9 |

| Bedroom 1 (trial 2) | 120, static | 33.0 ± 3.2 | 0.43 ± 0.05 | 8.0 ± 1.0 | ||

| 10, disturbed | 36.7 ± 9.7 | 0.54 ± 0.24 | 120 ± 54.4 | |||

| Bedroom 2 | 15 × 15 × 8 | 120, static | 59.5 ± 2.0 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 30.0 ± 3.7 | |

| 10, disturbed | 27.4 ± 4.2 | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 78.0 ± 11.4 | |||

| Bedroom 3 | 20 × 25 × 8 | 120, static | 47.9 ± 10.5 | 0.92 ± 0.39 | 17.1 ± 7.2 | |

| 10, disturbed | 35.8 ± 3.2 | 0.48 ± 0.06 | 107 ± 13.7 | |||

| Outside air | 30 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| 60 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| 90 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| 120 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Length by width by height.

Room were sampled under static and/or disturbed conditions for the noted times. Air disturbance was accomplished using 20-inch box fans on a “high” setting. Disturbance was allowed for 5 minutes prior to starting the SpinCon collection.

Data are means ± standard deviations. Values are based on that for PBS alone (average of eight separately run samples). Values represent triplicate wells.

Means ± standard deviations are shown. Values were derived from an ELISA-based macrocyclic trichothecene standard curve. Values represent triplicate wells.

Means ± standard deviations are shown. Values represent triplicate wells. Estimated values are based on the average trichothecene equivalents for the entire collected sample, collection time, and flow rate of the SpinCon sampler. For example, a total of 54 m3 of air was collected for each 120-minute sample. Given a final working volume of 1 milliliter, trichothecene concentrations were then estimated from values obtained from ELISA testing.

FIG. 3.

Box plot data for average trichothecene equivalents per m3 of sampled air in Stachybotrys-contaminated and control indoor environments. Trichothecene equivalents (in picograms) were determined using a macrocyclic trichothecene standard curve. Graph A shows the data distribution from 120-min (m) control and test samples under static (S) and disturbed (D) conditions and from 30-minute samples from disturbed test environments. Medians (solid lines) and means (dotted lines) are shown. The 10th and 90th percentiles are designated by the bottom and top error bars, respectively. The 25th and 75th percentiles are indicated by the bottoms and tops of the boxes, respectively. Outliers are designated as filled circles above and/or below the plot. Test environments were compared to control environments (**) using a Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks. Graph B shows the data distribution from control and test environments sampled for 10 min under disturbed conditions. Test environments were compared to controls by using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. *, statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

Table 7 shows the results for the two buildings that were sampled using the Andersen PUF high-volume sampler. Data are presented similarly to those in Table 2, but with an additional column noting the pore size of the glass microfiber filter used. For each sampling time in the test building, the 2.7-μm-pore-size filter in the setup demonstrated higher ELISA reactivity than the second (<0.3-μm-pore-size) filter. Values were highest for the 24-hour sampling period, followed by the 72- and 48-hour collection intervals. A general trend was not observed, but statistically higher trichothecene concentrations were seen with the filters from the environment with known Stachybotrys chartarum growth than with those from the control building. Percentages of inhibition and trichothecene equivalents observed for the one control room tested with the PUF sampler were lower than those for controls tested with the SpinCon sampler (Table 6).

TABLE 7.

Air sampling analyses of Andersen PUF-sampled test and control indoor environments

| Building and room | Dimensions of room (ft)a | Filter pore size (μm) | Sampling time (h) | Avg % ELISA inhibitionb | Avg trichothecene equivalentsc (ng/ml) | Avg trichothecene equivalents/m3 of sampled aird (pg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test building 8, garage storage closet | 3 × 6 × 8 | 2.7 | 24 | 79.2 ± 1.6 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 62.6 ± 12.3 |

| <0.3 | 40.1 ± 6.3 | 0.62 ± 0.04 | 6.9 ± 2.1 | |||

| 2.7 | 48 | 72.0 ± 1.5 | 6.2 ± 0.9 | 14.3 ± 2.0 | ||

| <0.3 | 23.9 ± 3.1 | 0.77 ± 0.09 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | |||

| 2.7 | 72 | 80.7 ± 0.4 | 16.3 ± 0.9 | 25.1 ± 1.4 | ||

| <0.3 | 52.4 ± 2.5 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | |||

| Control building 1, room 4 | 20 × 10 × 10 | 2.7 | 24 | 21.7 ± 1.5 | 0.41 ± 0.02 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| <0.3 | 24 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Length by width by height.

Data are means ± standard deviations. Values are based on that for PBS alone (average of eight separately run samples). Values represent triplicate wells.

Means ± standard deviations are shown. Values were derived from an ELISA-based macrocyclic trichothecene standard curve. Values represent triplicate wells.

Means ± standard deviations are shown. Values represent triplicate wells. Estimated values are based on the average trichothecene equivalents for the entire collected sample, collection time, and flow rate of the Andersen sampler. For example, a total of 216 m3 of air was collected for each 24-hour sample. Given a final working volume of 1 milliliter, trichothecene concentrations were then estimated from values obtained from ELISA testing.

Fungal conidia and indoor allergen cross-reactivity.

Of the fungi tested, only two demonstrated significant (P < 0.05) ELISA cross-reactivity. S. chartarum strain 201212 was significantly (P < 0.05) different from the extracting solvent (PBS) alone at all three tested conidium concentrations. The average percentages of inhibition were 93.6, 92.5, and 83.7% at 5 × 105, 5 × 104, and 5 × 103 conidia/ml, respectively. Of the remaining fungi tested, only S. chartarum strain 9633 demonstrated significant (P < 0.05) ELISA cross-reactivity, and then only at the highest concentration (9.2% at 1 × 106 conidia/ml). Can f 1, Der p 1, and Fel d 1 demonstrated no cross-reactive ELISA binding.

DISCUSSION

In this study, through the use of two types of high-volume air samplers in conjunction with sensitive and specific ELISA technology, we were successful in demonstrating the presence of airborne macrocyclic trichothecene mycotoxins in a controlled situation and eight native Stachybotrys chartarum-contaminated indoor environments. It should be noted that the observed positive results were likely influenced, albeit slightly, by nonspecific binding to other airborne constituents. This is based on the false-positive results observed in control buildings (Table 6). We hypothesize this nonspecificity to be inherent to the antibody. The antibody used for detection in our analyses was raised against satratoxin G, a compound with a molecular weight of 500. Cross-reactivity and/or nonspecific binding to other similarly structured airborne compounds (e.g., volatile organic compounds, other low-molecular-weight microbial toxins, protein haptens, etc.) is expected, particularly when considering the complex composition of indoor air. Further support for this observed phenomenon lies in the fact that we were testing with a polyclonal antibody, which in itself has an associated degree of nonspecificity. We previously demonstrated the highly specific nature of the ELISA (4), and because other common indoor fungi demonstrated no ELISA cross-reactivities in these studies, our results likely reflect the presence of airborne S. chartarum macrocyclic trichothecene mycotoxins in the sampled buildings contaminated with this organism. However, for future studies, it would be advantageous to incorporate additional means of analysis to confirm the presence of airborne trichothecene mycotoxins.

Seven of the eight Stachybotrys-contaminated environments were tested using a SpinCon PAS 450-10 high-volume wet concentration bioaerosol sampler. In general, our data demonstrated an increase in airborne mycotoxin concentrations in relation to increased Stachybotrys conidium and debris counts. This was an expected result since the two primary mycotoxins produced by S. chartarum (satratoxins G and H) are known to be associated primarily with conidia (19) and, consequently, fungal fragments (4, 17). In a similar manner, invasive inspection techniques and remediation result in an extensive release of airborne particulate matter, including conidia and mycotoxins. This poses a potential health risk to remediators and emphasizes the need for personal protective equipment while working in mold-contaminated areas.

The mechanism used to disturb the air for these experiments was a means to shorten the overall sampling times. Such an intense disturbance and consequent release of particulates inclusive of S. chartarum conidia would not be expected to occur in native environments. However, subtler disturbance mechanisms (human and mechanical vibrations, ceiling fans, air conditioning units, etc.) are hypothesized to cause the persistent release of such particulate matter over a longer period of time. This supports the idea that adverse human health effects in mold-contaminated buildings are a result of chronic more often than acute exposure. Longer disturbances under intense conditions resulted in lower airborne trichothecene concentrations. The cause for this phenomenon is not completely clear, but here we hypothesize three reasons. First, although rooms were closed off from the rest of the building during sampling, they were not completely sealed. During fan operation, we likely created a positive-pressure environment. Particulate matter and associated mycotoxins could have exited the sampling area via the path of least resistance (e.g., under doors, through wall sockets, wall cracks, etc.). Second, operation of the fans caused an intense wind velocity in the rooms that could have been large enough to overpower the collection capacity of the SpinCon sampler. In other words, particles of interest could have been rendered unattainable by our sampling method. Third, because the SpinCon instrument is a high-volume sampler, it is possible that the majority of the trichothecene-containing particulates were collected within the first few minutes of sampling. These issues aside, we believe we have developed a means to collect and analyze aerosolized Stachybotrys chartarum macrocyclic trichothecene mycotoxins in buildings contaminated with this organism. Additionally, our sampling techniques could be modified to test for other airborne constituents, such as allergens, endotoxin, and/or mycotoxins produced by other fungi. Based on our data, this would involve an initial 2-hour or longer static sample to evaluate airborne contamination in the native setting. This would be followed by a much shorter sampling period (ideally, 10 min) under air disturbance conditions to assess the potential for trichothecenes to become airborne in that environment.

Our testing methods were highly specific for buildings contaminated with S. chartarum. The specific nature of our methods was seen in both controlled and natural settings. For controlled analyses, ELISA cross-reactivity was tested with 13 strains of fungi (frequently isolated from indoor environments) that do not produce macrocyclic trichothecenes. Only S. chartarum strain 9633 demonstrated significant cross-reactivity, and then only at the highest conidium concentration tested (1 × 106 conidia/ml). This could have been due to a basal level of trichothecene production that was not detectable by previously described analytical methods (22, 23, 26). Regarding the specificity of our testing in natural settings, certain areas (a bedroom in test building 1 and all of building 7) were heavily contaminated with fungi; however, no Stachybotrys growth sites were observed, and consequently, airborne Stachybotrys conidium counts were zero. The results obtained from sampling in these areas were similar to those for negative controls. The bedroom in building 1 demonstrated significantly (P < 0.05) higher values after 30 min of collection under disturbed conditions, likely because these values were compared to those obtained following 2-hour sampling under static conditions. Even when high concentrations of other fungi were present (such as Chaetomium and/or Memnoniella), positive results were only seen for environments contaminated with Stachybotrys chartarum during the time of sampling.

Building 8 was unique in that we tested the hypothesis that airborne trichothecene mycotoxins were present on particulates smaller than fungal conidia. This is important because in the indoor environment, fragments and other highly respirable particles greatly outnumber intact fungal conidia (17). Many widely used techniques such as bulk sampling (e.g., the adhesive tape technique, surface swabs, the collection of bulk materials, etc.) and viable/nonviable airborne conidium assessments (e.g., volumetric spore traps, Andersen impaction devices, etc.) are not designed for the collection and analysis of these potential health hazards. Previously, by using a controlled filtration setup (similar to the one depicted in Fig. 1), we were able to demonstrate S. chartarum trichothecene mycotoxins on particles smaller than conidia (4). In the current study, we were able to show this same phenomenon after 24, 48, and 72 h of high-volume air sampling in a native mold-contaminated building. These findings indicate the need to collect this class of particles (in addition to larger particulate matter such as intact conidia) when conducting indoor air quality investigations.

Our study shows that macrocyclic trichothecene mycotoxins from Stachybotrys chartarum can become airborne in indoor environments contaminated with this organism. Our data suggest the need to test for these potential occupant health risks during indoor air quality investigations. Although we were able to semiquantitate airborne concentrations, it is still not known what levels of these mycotoxins pose a definitive human health risk. Furthermore, normal background levels (if they do exist) have not been characterized. Future research should focus on the relationship between respiratory exposure to airborne trichothecenes in fungus-contaminated buildings and human health issues resulting from such exposures. Additionally, alternative assays or means to measure airborne trichothecenes more accurately in such environments should be researched and developed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sceptor Industries, Inc., Kansas City, Missouri, and EnviroLogix, Portland, Maine, for their generous donations of SpinCon bioaerosol samplers and QuantiTox kits, respectively. We also thank Assured IAQ, Dallas, Texas, for their continued support and Matthew Fogle for his technical contributions. In conclusion, we give special thanks to all of the home and building owners who kindly allowed us into their dwellings to complete this research.

This work was supported by a grant from the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (010674-0006-2001) and by a Center of Excellence Award from Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center. Additional funding was provided by the UT-Houston School of Public Health Pilot Research Projects in Occupational Safety and Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson, M. A., M. Nikulin, U. Koljalg, M. C. Andersson, F. Rainey, K. Reijula, E.-L. Hintikka, and M. Salkinoja-Salonen. 1997. Bacteria, molds, and toxins in water-damaged building materials. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:387-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes, C., S. Buckley, F. Pacheco, and J. Portnoy. 2002. IgE-reactive proteins from Stachybotrys chartarum. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 89:29-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes, C., K. Schreiber, F. Pacheco, J. Landuyt, F. Hu, and J. Portnoy. 2000. Comparison of outdoor allergenic particles and allergen levels. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 84:47-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brasel, T. L., D. R. Douglas, S. C. Wilson, and D. C. Straus. 2004. Detection of airborne Stachybotrys chartarum macrocyclic trichothecene mycotoxins on particulates smaller than conidia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:114-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cage, B. R., K. Schreiber, C. Barnes, and J. Portnoy. 1996. Evaluation of four bioaerosol samplers in the outdoor environment. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 77:401-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chao, H. J., D. K. Milton, J. Schwartz, and H. A. Burge. 2001. Dustborne fungi in large office buildings. Mycopathologica 154:93-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung, Y.-J., B. Jarvis, T. Heekyung, and J. J. Pestka. 2003. Immunochemical assay for satratoxin G and other macrocyclic trichothecenes associated with indoor air contamination by Stachybotrys chartarum. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 13:247-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Croft, W. A., B. B. Jarvis, and C. S. Yatawara. 1986. Airborne outbreak of trichothecene toxicosis. Atmos. Environ. 20:549-552. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dales, R. E., R. Burnett, and H. Zwanenburg. 1991. Adverse health effects among adults exposed to home dampness and molds. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 143:505-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Hoog, G. S., J. Guarro, J. Gené, and M. J. Figueras. 2000. Atlas of clinical fungi, 2nd ed. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

- 11.Dharmage, S., M. Bailey, J. Raven, K. Abeyawickrama, D. Cao, D. Guest, J. Rolland, A. Forbes, F. Thien, M. J. Abramson, and E. H. Walters. 2002. Mouldy houses influence symptoms of asthma among atopic individuals. Clin. Exp. Allergy 32:714-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elidemir, O., G. N. Colasurdo, S. N. Rossman, and L. L. Fan. 1999. Isolation of Stachybotrys from the lung of a child with pulmonary hemosiderosis. Pediatrics 104:964-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erwin, E. A., J. A. Woodfolk, N. Custis, and T. A. Platts-Mills. 2003. Animal danders. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 23:469-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Etzel, R. A., E. Montana, W. G. Sorenson, G. J. Kullman, T. M. Allan, D. G. Dearborn, D. R. Olson, B. B. Jarvis, and J. D. Miller. 1998. Acute pulmonary hemorrhage in infants associated with exposure to Stachybotrys atra and other fungi. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 152:757-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feinberg, B., and C. S. McLaughlin. 1998. Biochemical mechanism of action of trichothecene mycotoxins, p. 27. In V. R. Beasley (ed.), Trichothecene mycotoxicosis: pathophysiologic effects, vol. 1. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodwin, W., C. D. Haas, C. Fabian, I. Heller-Bettinger, and B. Hoogstraten. 1978. Phase I evaluation of anguidine (diacetoxyscirpenol, NSC-141537). Cancer 42:23-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorny, R. L., T. Reponen, K. Willeke, D. Schmechel, E. Robine, M. Boissier, and S. A. Grinshpun. 2002. Fungal fragments as indoor air biocontaminants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3522-3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gravesen, S., P. A. Nielsen, R. Iversen, and K. F. Nielsen. 1999. Microfungal contamination of damp buildings—examples of risk constructions and risk materials. Environ. Health Perspect. 107:505-508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gregory, L., J. J. Pestka, D. G. Dearborn, and T. G. Rand. 2004. Localization of satratoxin-G in Stachybotrys chartarum spores and spore-impacted mouse lung using immunocytochemistry. Toxicol. Pathol. 32:26-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison, J., C. A. Pickering, E. B. Faragher, P. K. Austwick, S. A. Little, and L. Lawton. 1992. An investigation of the relationship between microbial and particulate indoor air pollution and the sick building syndrome. Respir. Med. 86:225-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins, J. A., M. Cooper, L. Schroeder-Tucker, S. Black, D. Miller, J. S. Karns, E. Manthey, R. Breeze, and M. L. Perdue. 2003. A field investigation of Bacillus anthracis contamination of U.S. Department of Agriculture and other Washington, D.C., buildings during the anthrax attack of October 2001. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:593-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinkley, S., E. P. Mazzola, J. C. Fettinger, Y. Lam, and B. Jarvis. 2000. Atranones A-G, from the toxigenic mold Stachybotrys chartarum. Phytochemistry 55:663-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinkley, S. F., and B. B. Jarvis. 2001. Chromatographic method for Stachybotrys toxins. Methods Mol. Biol. 157:173-194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hodgson, M. J., P. Morey, W.-Y. Leung, L. Morrow, D. Miller, B. B. Jarvis, H. Robbins, J. F. Halsey, and E. Storey. 1998. Building-associated pulmonary disease from exposure to Stachybotrys chartarum and Aspergillus versicolor. J. Environ. Med. 40:241-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hossain, M. A., M. S. Ahmed, and M. A. Ghannoum. 2004. Attributes of Stachybotrys chartarum and its association with human disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 113:200-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jarvis, B. B., W. G. Sorenson, E. L. Hintikka, M. Nikulin, Y. Zhou, J. Jiang, S. Wang, S. Hinkley, R. A. Etzel, and D. Dearborn. 1998. Study of toxin production by isolates of Stachybotrys chartarum and Memnoniella echinata isolated during a study of pulmonary hemosiderosis in infants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3620-3625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaward, F. M., N. J. Farrar, T. Harner, A. J. Sweetman, and K. C. Jones. 2004. Passive air sampling of PCBs, PBDEs, and organochlorine pesticides across Europe. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38:34-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johanning, E., R. Biagini, D. Hall, P. Morey, B. Jarvis, and P. Landsbergis. 1996. Health and immunology study following exposure to toxigenic fungi (Stachybotrys chartarum) in a water damaged office environment. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 68:207-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehrer, S. B., L. Aukrust, and J. E. Salvaggio. 1983. Respiratory allergy induced by fungi. Clin. Chest Med. 4:23-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maritta, S., M. S. Jaakkola, H. Nordman, R. Piipari, J. Uitti, J. Laitinen, A. Karjalainen, P. Hahtola, and J. K. Jaakkola. 2002. Indoor dampness and molds and development of adult-onset asthma: a population-based incident case-control study. Environ. Health Perspect. 110:543-547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin, J. W., D. C. Muir, C. A. Moody, D. A. Ellis, W. C. Kwan, K. R. Solomon, and S. A. Mabury. 2002. Collection of airborne fluorinated organics and analysis by gas chromatography/chemical ionization mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 74:584-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mason, C. D., T. G. Rand, M. Oulton, J. MacDonald, and M. Anthes. 2001. Effects of Stachybotrys chartarum on surfactant convertase activity in juvenile mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 172:21-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy, W. K., M. A. Burgess, M. Valdivieso, R. B. Livingston, G. P. Bodey, and E. J. Freireich. 1978. Phase I clinical evaluation of anguidine. Cancer Treat. Rep. 62:1497-1502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pasanen, A.-L., M. Nikulin, M. Tuomainen, S. Berg, P. Parikka, and E.-L. Hintikka. 1993. Laboratory experiments on membrane filter sampling of airborne mycotoxins produced by Stachybotrys atra corda. Atmos. Environ. 27A:9-13. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pessi, A.-M., J. Suonketo, M. Pentti, M. Kurkilahti, K. Peltola, and A. Rantio-Lehtimaki. 2002. Microbial growth inside insulated external walls as an indoor air biocontamination source. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:963-967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Portnoy, J., J. Landuyt, F. Pacheco, S. Flappan, S. Simon, and C. Barnes. 2000. Comparison of the Burkard and Allergenco MK-3 volumetric collectors. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 84:19-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rand, T. G., K. White, A. Logan, and L. Gregory. 2002. Histological, immunohistochemical and morphometric changes in lung tissue in juvenile mice experimentally exposed to Stachybotrys chartarum spores. Mycopathologica 156:119-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rao, C. Y. 2000. Toxigenic fungi in the indoor environment, p. 46.1-46.19. In J. D. Spengler, J. M. Samet, and J. F. McCarthy (ed.), Indoor air quality handbook. McGraw-Hill, Washington, D.C.

- 39.Revankar, S. G. 2003. Clinical implications of mycotoxins and Stachybotrys. Am. J. Med. Sci. 325:262-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scheel, C. M., W. C. Rosing, and A. L. Farone. 2001. Possible sources of sick building syndrome in a Tennessee middle school. Arch. Environ. Health 56:413-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schick, M. R., G. R. Dreesman, and R. C. Kennedy. 1987. Induction of an anti-hepatitis B surface antigen response in mice by noninternal image (Ab2a) anti-idiotypic antibodies. J. Immunol. 138:3419-3425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shoeib, M., and T. Harner. 2002. Characterization and comparison of three passive air samplers for persistent organic pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36:4142-4151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smoragiewicz, W., B. Cossette, A. Boutard, and K. Krzystyniak. 1993. Trichothecene mycotoxins in the dust of ventilation systems in office buildings. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 65:113-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]