Abstract

Paenibacillus polymyxa is a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium with a broad host range, but so far the use of this organism as a biocontrol agent has not been very efficient. In previous work we showed that this bacterium protects Arabidopsis thaliana against pathogens and abiotic stress (S. Timmusk and E. G. H. Wagner, Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 12:951-959, 1999; S. Timmusk, P. van West, N. A. R. Gow, and E. G. H. Wagner, p. 1-28, in Mechanism of action of the plant growth promoting bacterium Paenibacillus polymyxa, 2003). Here, we studied colonization of plant roots by a natural isolate of P. polymyxa which had been tagged with a plasmid-borne gfp gene. Fluorescence microscopy and electron scanning microscopy indicated that the bacteria colonized predominantly the root tip, where they formed biofilms. Accumulation of bacteria was observed in the intercellular spaces outside the vascular cylinder. Systemic spreading did not occur, as indicated by the absence of bacteria in aerial tissues. Studies were performed in both a gnotobiotic system and a soil system. The fact that similar observations were made in both systems suggests that colonization by this bacterium can be studied in a more defined system. Problems associated with green fluorescent protein tagging of natural isolates and deleterious effects of the plant growth-promoting bacteria are discussed.

Paenibacillus polymyxa (previously Bacillus polymyxa) is one of many plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and is known to have a broad host plant range. It has been isolated from the rhizospheres of wheat and barley (30), white clover, perennial ryegrass, crested wheatgrass (19), lodgepole pine (18), Douglas fir (43), green bean (37), and garlic (24). In addition to several P. polymyxa antagonistic effects reported previously, we have shown that P. polymyxa antagonizes oomycetic pathogens (49). Due to its broad host range, its ability to form endospores, and its ability to produce different kinds of antibiotics, P. polymyxa is a potential commercially useful biocontrol agent. So far, most studies on the biocontrol activity of P. polymyxa have concentrated on the production of different antibiotic substances. Although biocontrol in general has been used for decades, its application has not been very consistent, perhaps due in part to an incomplete understanding of the biological control system (14, 15). Plant roots are not passive targets for soil organisms. Therefore, in addition to understanding the agent itself and its interaction with the pathogen, knowledge of the interaction of the biological control agent with the plant root is required. Although the plant growth-promoting activity of P. polymyxa has been the subject of numerous studies (references 2, 3, and 53 and references therein), the pattern of colonization of this bacterium on host plants has not been studied in detail previously.

We previously reported that a natural isolate of P. polymyxa induces drought tolerance and antagonizes pathogens in Arabidopsis thaliana. These effects were observed with a gnotobiotic system and with soil (48, 49). These studies indicated that, aside from the beneficial effects observed, inoculation of A. thaliana by P. polymyxa (in the absence of biotic or abiotic stress) resulted in a 30% reduction in plant growth, as well as a stunted root system, compared to noninoculated plants. This indicated that there was a mild pathogenic effect (48, 49). Hence, under these conditions, P. polymyxa could be considered a deleterious rhizobacterium (DRB) (46). To address the relationship between the beneficial and harmful effects of P. polymyxa on A. thaliana, we decided to characterize the colonization process.

Effective colonization of plant roots by PGPR plays an important role in growth promotion, irrespective of the mechanism of action (production of metabolites, production of antibiotics against pathogens, nutrient uptake effects, or induced plant resistance) (5, 40). It is now common knowledge that bacteria in natural environments persist by forming biofilms (11). Biofilms are highly structured, surface-attached communities of cells encased in a self-produced extracellular matrix (10).

Here we describe tagging of a natural isolate of P. polymyxa with the green fluorescent protein (GFP). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on tagging of P. polymyxa, and our findings may provide useful information for further studies of colonization by gram-positive bacteria. We also describe the localization of the bacteria on roots in a gnotobiotic system and in a soil system, as determined by fluorescent microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The data obtained indicate that P. polymyxa forms biofilms on plant root tips and enters intercellular spaces but does not spread throughout the plant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material and growth conditions.

Seeds of A. thaliana ecotype C24 were surface sterilized by incubation in a saturated and filtered aqueous calcium chlorate solution for 30 min, followed by repeated washes in sterile distilled water. The seeds were then sown on MS-2 medium (34) for germination. Plants were then transferred to new culture dishes with MS medium and subsequently grown for 2 weeks in a growth chamber at 22°C with a 16-h light regimen. The light intensity used was 200 microeinsteins m−2 s−1. Care was taken to maintain sterility during growth and handling of the plants.

Inoculation of plants with P. polymyxa.

P. polymyxa strains B1 and B2 (29-31) were grown in L medium (33) at 30°C in 100-ml flasks to the late log phase. After 2 weeks of growth, plants were inoculated by soaking their roots in 10-ml diluted overnight cultures of P. polymyxa (∼106 bacteria ml−1). For gnotobiotic studies, the pattern of colonization by the bacteria was monitored once per hour. For soil experiment, plantlets were planted in sterilized soil or in nonsterile greenhouse soil and monitored after 3, 6, 7, and 14 days.

Plasmids and bacterial transformation.

Two shuttle plasmids capable of replication in both Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis were used to introduce plasmid-borne gfp genes into P. polymyxa isolates B1 and B2. Plasmid pBSVG101 (5.4 kb) is a low-copy-number, tetracycline resistance-conferring plasmid that carries a 786-bp gfp fragment from pGFP (Clontech Laboratories) that is inserted between the HindIII and EcoRI restriction sites of shuttle vector pHY300PLK (22). The expression of gfp is driven by a bsr promoter. This plasmid has been used for GFP tagging of B. subtilis (22).

Plasmid pCM20 (a gift from S. Molin, The Technical University of Denmark) is an 8.7-kb pAMβ1 replicon plasmid with a P15A replicon capable of replicating in E. coli. The resident gfp gene was inserted into the unique EcoRV site of the vector. This plasmid confers erythromycin resistance.

Electroporation of P. polymyxa isolates was carried out as described previously (41), using a Gene Pulser apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA). Cultures were grown to concentrations of about 107 CFU ml−1. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (10,400 × g, 15 min), washed twice in bidistilled water and once in PEB electroporation buffer (32), and resuspended in electroporation buffer at 1/100 of the original culture volume. Ten microliters of plasmid DNA was mixed with 0.8 ml of a cell suspension containing 5 × 109 CFU in a chilled Gene Pulser cuvette (interelectrode gap, 0.4 cm) and kept on ice for about 5 min. One milliliter of GB broth was immediately added to the cuvette following application of a high-voltage electric pulse. The cell suspension was kept on ice for 15 min, and 7 ml of GB broth was added. The cultures were incubated at 30°C for 2 h, concentrated by centrifugation to 0.8 ml, and plated. E. coli transformants were selected on LB plates containing 10 μg tetracycline ml−1 or 150 μg erythromycin ml−1. P. polymyxa transformants were selected on GB medium plates (41) containing 10 μg tetracycline ml−1 or 3 μg erythromycin ml−1.

Plasmid DNA was prepared using a QIAGEN plasmid isolation kit modified so that, for P. polymyxa, 1 mg lysozyme ml−1 was added to the P1 solution, and incubation was carried out at 37°C for 1 h.

Determination of the sequence of 16S rRNA genes.

The sequence of the proximal ∼500 bp of the 16S rRNA genes of the P. polymyxa isolates was determined with a PCR cycle sequencing kit (Promega) using an ABI370 sequencer, and this was followed by comparisons with available entries using BLAST searches. The primers used for amplification of a 16S rRNA gene segment were located at the 5′ end of the gene (primer S [5′-AGA GTT TGA TTC TGG CTC-3′]) and between variable regions V8 and V9 (primer R [5′-CGG GAA CGT ATT CAC CG-3′]); the size of the amplified DNA fragment was 1.4 kbp. PCR amplification was performed in a 25-μl (total volume) mixture using Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer) and a Rapid Cycler (Idaho Technologies). The amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 2 min at 72°C and then a final extension step consisting of 5 min at 72°C.

Detection and enumeration of P. polymyxa isolate B1::pCM20 on A. thaliana roots.

For the gnotobiotic system studies, control plants were soaked in 10-fold-diluted L medium, and the colonization pattern of the bacteria was monitored each hour during the first 12 h of inoculation. Dilution of the cultures, as well as medium (in controls), was used to reduce the osmotic stress to the plants caused by the high salt content of the medium. The induced systemic resistance effect (48) was reproduced using diluted cultures. For studies in soil, root samples were obtained at the time of planting and 1, 3, 7, and 14 days after planting.

For determination of the numbers of bacteria, the soil was removed from the roots. Individual roots were blended in 10 mM MgSO4 for about 3 min. For endophyte enumeration, the plant roots were surface sterilized in a surface sterilization solution (1% sodium hypochlorite, 0.1% sodium lauryl sulfate, 0.2% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]). The roots were vortexed for 2 min, and this was followed by four washes with sterilized water; then the roots were examined with a microscope to ensure that no fluorescent cells remained (2). In addition, the wash solutions from the last root rinse were cultured to determine the efficiency of sterilization. Roots were then macerated using a mortar, and the numbers of CFU were determined by plating preparations on GB medium containing erythromycin (10 μg ml−1).

Microscopy.

To visualize single GFP-tagged bacterial cells, overnight cultures were centrifuged, resuspended in PBS, spread and air dried on poly-l-lysine-coated slides, and subsequently mounted under coverslips in PBS containing 50% glycerol. Fluorescence microscopy was carried out using a Zeiss Axioplan II imaging fluorescence microscope equipped with appropriate filter sets, an Axiocam charge-coupled device camera, and the AXIOVISION software (Carl Zeiss Light Microscopy). Digital images for the figures were assembled using the Adobe Photoshop software. Computational quantitation of fluorescence levels was done by measuring pixel intensities on the digital images generated with the charge-coupled device camera. The resulting values were expressed in arbitrary units.

To visualize the localization of P. polymyxa B1::pCM20 in the gnotobiotic system, A. thaliana roots were inoculated as described above and examined by fluorescence microscopy at various times. To improve the depth resolution, some experiments were conducted after sectioning. Seedlings were first surface sterilized as described above, and 20-μm cryostat root sections were used for subsequent deconvolution imaging. Z stacks were collected at 0.1-μm steps, and the resulting images were deconvoluted using the Nearest Neighbor algorithm of the Axiovision software (see Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

SEM micrographs of plant roots colonized by P. polymyxa B1::pCM20. P. polymyxa B1::pCM20 colonization and biofilm formation on A. thaliana roots in the gnotobiotic system after 2 h of colonization (A, C, and E) and in nonsterile soil assays after 1 week of colonization (B, D, and F) are compared. Roots were prepared and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Images were taken at the root tips (A, B, C, and D) and at tip-distal regions (E and F). Note the biofilm formation in the gnotobiotic system (A and C) and the soil system (B and D) around the root tip. Many fewer bacteria than in the biofilm region colonize the regions behind the root tip in the gnotobiotic system (E) and in the soil system (F). In the nonsterile system only P. polymyxa was present in the biofilm-covered regions (D), whereas P. polymyxa cells mixed with indigenous bacteria were found in the distant regions of the plant root (F). Note the degradation pattern on the root tip indicated by arrows in panel B.

We used a Leica MZ FLIII fluorescence stereomicroscope to visualize the localization of P. polymyxa B1::pCM20 on plant roots in soil. Plants were inoculated as described above, planted in soil in petri dishes, and grown for up to 2 weeks. Since we tried to avoid interference with the pattern of bacterial colonization on the plants by the sample preparation process, the preparations were visualized by turning the petri dishes upside down and exposing the plant roots to the excitation spectrum. Natural fluorescence from plant roots and from substances in the soil sometimes interferes with fluorescence from gfp-transformed cells (1). The resolution is generally not sufficient to see the bacteria. Hence, scanning electron microscope studies were also conducted. Whole inoculated roots or parts of inoculated roots were fixed in glutaraldehyde as described by Smyth et al. (44) or in a solution containing formaldehyde (13). The samples were dehydrated using a graded ethanol series and critical point dried in CO2. The pressure was decreased very slowly to prevent tissue damage. Leaf samples were mounted on stubs and shadowed with gold (22 nm) before they were viewed with a Philips Autoscan SEM. All images were computer processed.

RESULTS

GFP tagging of P. polymyxa isolates.

Two natural isolates of P. polymyxa, B1 and B2 (30), were chosen as candidates for localization studies. Both of these isolates confer protection against pathogens and abiotic stress in A. thaliana (48, 49). Determination of the DNA sequence of a segment of 16S rRNA (see Materials and Methods) showed that B1 and B2 had identical sequences, and both sequences differed by only one nucleotide from the sequence of a P. polymyxa strain (the difference was a change from G to A at position 453; GenBank accession number AF515611), which indicated that both isolates should be classified as P. polymyxa.

Two gfp-carrying plasmids, pBSVG101 and pCM20 (see Materials and Methods), which are known to replicate in B. subtilis, were chosen for tagging. Initial transformation attempts and natural competence protocols failed for both plasmid-strain combinations (data not shown), whereas both plasmids could be introduced by electroporation (41).

For colonization studies, it is advantageous if individual tagged cells have high GFP-dependent fluorescence intensities but exhibit only small cell-to-cell variations. For the initial characterization, observations of transformant colonies on a UV table (data not shown) and fluorescence microscopy were used. No fluorescence was detected with the transformed P. polymyxa isolate B2 (data not shown), whereas cells of isolate B1 carrying either of the two plasmids were fluorescent (Fig. 1). Great fluorescence intensity variations were seen with cells carrying pBSVG101, and the intensities ranged from very bright to background emission. In contrast, cells carrying pCM20 showed more uniform fluorescence, although the level was lower than that of some of the pBSVG101-carrying cells. Maximal fluorescence was observed after 24 h with both plasmids, and the fluorescence remained stable for several days.

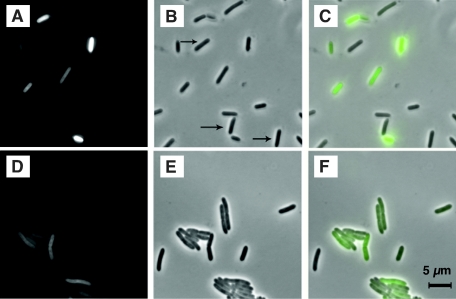

FIG. 1.

Micrographs of GFP-tagged P. polymyxa isolate B1 cells: fluorescence micrographs (GFP) (A and D) and phase-contrast micrographs (B and E) of bacterial cells containing plasmid pBSVG101 (A and B) or pCM20 (D and E) after 24 h of incubation in LB. Panel C is an overlay of panels A and B, and panel F is an overlay of panels B and D. The arrows indicate cells with low levels of fluorescence.

For quantitation, the fluorescence intensities of 100 randomly chosen individual cells carrying either plasmid pBSVG101 or plasmid pCM20 were determined. Figure 2 shows a diagram of the numbers of cells that fell into different intensity intervals. From this diagram it is clear that P. polymyxa isolate B1::pCM20 met the requirement for relatively uniform signals, whereas transformants carrying pBSVG101 showed great variation in intensity. The growth rate of the B1::pCM20 strain was very similar to that of the plasmid-free parent, whereas the growth rate of strain B1::pBSVG101 was about 40% lower. Furthermore, plasmid pCM20 was stably maintained without selection, and thus P. polymyxa B1::pCM20 was chosen for further studies.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of fluorescence signal intensities of single P. polymyxa B1 cells. Fluorescence intensities of individual cells were measured. For each strain-plasmid combination, 100 cells were measured. The approximate detection limit was 100 U.

P. polymyxa localization on A. thaliana roots in the gnotobiotic system and in soil.

One of the questions raised in this work concerned whether the gnotobiotic model system can be used for further studies of the complexity of the P. polymyxa-plant interaction. It is well known that the colonization in gnotobiotic systems may differ from that in a less well-defined soil system. Thus, we asked whether our model reflects the natural pattern of colonization in soil. With this in mind, we used low-magnification microscopy to visualize bacterial colonization directly in soil and to compare it to colonization in the gnotobiotic system. In order to distinguish the bacteria and their effects on the roots in the two systems, SEM was employed to examine root samples from parallel treatments.

(i) P. polymyxa colonization of A. thaliana roots in a gnotobiotic system.

P. polymyxa isolate B1::pCM20 was used to inoculate A. thaliana roots. In the gnotobiotic system, roots were analyzed at various times after inoculation for up to 24 h. Colonization occurred preferentially in defined regions of the elongation and differentiation zones of the plant primary roots. The first site of colonization was the zone of cell elongation at the root tip, where bacteria started to accumulate as microcolonies. A biofilm consisting of bacterial cells and a semitransparent material suggestive of an extracellular matrix was formed within 2 h (106 cells g roots−1) (Fig. 3A, 4C, and 5). Within 2 h of inoculation, root caps sometimes became separated from the main roots (data not shown). Bacterial colonization consisting of a low number of single cells was observed in the regions behind the root tip (Fig. 4E). Inspection of the root tip at a higher magnification and counting of root-invading bacteria indicated that fluorescent bacteria entered intercellular spaces during the first few hours after inoculation (Fig. 5). This pattern of root invasion was well expressed at 5 h (the level of root-invading bacteria was estimated to be 105 cells g roots−1) (Fig. 3B and 5). Surface sterilization of the roots (see Materials and Methods) (2), cryosectioning, and deconvolution imaging were used to visualize the bacteria in 20-μm longitudinal sections. This technique avoids interpretation problems since the detection is quasi-three dimensional. The bacteria were not detected in the vascular cylinder but were present in the layers outside the pericycle (Fig. 3C). Due to the tight cover that the abundant colonizing cells formed, it was difficult to assess the damage caused by the bacteria. Nevertheless, indications of damage at the epidermal root cap caused by the bacteria during 5 h of incubation are shown in Fig. 3B. The colonization in the soil system involved lower numbers, and the damage caused by the bacteria was observed more easily in soil (Fig. 4B). During the longer inoculation period, a second biofilm zone formed in the root differentiation region, and the root became progressively more affected. At 24 h, the root was severely damaged (109 CFU g roots−1) (Fig. 5). To study whether this phenomenon might be an artifact due to high-moisture conditions in the artificial system, different rhizobacterial isolates, including Paenibacillus vortex (8), Pseudomonas fluorescens SS101 (12), and P. fluorescens A506::gfp2 (52), were similarly tested in an inoculation assay. In contrast to P. polymyxa, these rhizobacteria did not exhibit a preference for specific zones on Arabidopsis roots, nor did they show any root-invading ability during the first few hours of colonization (data not shown). However, after about 5 h of colonization, all strains studied started to cause some damage to the roots, although the damage was remarkably less than that observed with P. polymyxa.

FIG. 3.

Fluorescence (GFP) micrographs of plant roots colonized by P. polymyxa B1::pCM20. P. polymyxa colonization and biofilm formation on plant roots in the gnotobiotic experiments (A and B) and in the soil experiments (D, E, and F) are compared, and bacterial localization in intercellular spaces is shown in panel C. Roots were prepared and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. The roots in panels D, E, and F were visualized directly from soil. (A) Bacterial biofilm formation on an A. thaliana root in the gnotobiotic system after 2 h of incubation. (B) Bacterial biofilm formation in the gnotobiotic system after 5 h of incubation. Note that P. polymyxa B1::pCM20 is localized between A. thaliana root cells (arrows) (see panel C and Fig. 5) and that there is an indication of damage to the epidermal root cap. (C) Deconvoluted optical section of 20-μm slices of surface-sterilized A. thaliana roots, 5 h after inoculation. (D) Bacterial biofilm formation on an A. thaliana tap root after 1 week of colonization in the soil assay. (E) Bacterial biofilm formation on a barley (H. vulgare) root colonized by P. polymyxa B1::pCM20 in a soil assay after 1 week of incubation. (F) Control roots treated with a mock solution. Note that the bacterial accumulation (indicated by brackets) in the gnotobiotic system (A) and in soil (D and E) occurred mainly around the root tip.

FIG. 5.

Sizes of the P. polymyxa B1::pCM20 populations in the rhizoplane and endorhizosphere of A. thaliana in the gnotobiotic system and in soil. The data are expressed as log10 CFU per gram (fresh weight) of plant material. The error bars indicate standard deviations for four samples. Note the different time scales in the gnotobiotic system and the soil experiments.

(ii) P. polymyxa colonization of A. thaliana roots in a soil system.

To study the localization on A. thaliana roots in soil, gfp-tagged P. polymyxa cells were introduced into the plant rhizosphere by inoculation of 2-week-old seedlings (see Materials and Methods). The plants were monitored on the day of planting and on days 3, 6, 7, and 14. Bacterial accumulation, mainly around the root tip, was first observed on the third day of incubation (Fig. 5). A bacterial biofilm containing bacterial cells and surrounded by material suggestive of an extracellular matrix formed around the root tips after 1 week in both the nonsterile and sterile soil systems (Fig. 3D and 4B and D). Root tip epidermis degradation by the bacteria was obvious at that time in both systems (Fig. 4B). Clusters of indigenous bacteria that were present in nonsterile soil colonized all surfaces of the roots of the control Arabidopsis plants (plants not inoculated with P. polymyxa). Single P. polymyxa cells in populations of indigenous bacteria were found on P. polymyxa-inoculated roots in regions where biofilms were not formed (Fig. 4F). However, in the regions around the root tip that were covered with biofilm, only P. polymyxa colonization was observed. (Fig. 4B and D). As a reference, we also studied bacterial accumulation and biofilm formation on barley (Hordeum vulgare). Since P. polymyxa isolate B1 originally was isolated from the rhizosphere of barley, this system could serve as a more natural system for colonization. Figure 3E shows that the pattern of bacterial accumulation around the root tip and zones behind the root tip was similar to the pattern described above.

On the day of planting, P. polymyxa B1::pCM20 persisted on the plant at population densities between ca. 104 and 105 CFU g roots−1 in the gnotobiotic system, as well as in soil (Fig. 5). The population densities reached a plateau value of 107 CFU g−1 in soil after 1 week of growth. Bacterial numbers were also monitored inside the plant root. Invasion of root tissue outside the vascular cylinder started on day 3, and the maximum value (ca. 103 CFU g roots−1) was reached on day 7. No P. polymyxa cells were detected in plant leaves.

DISCUSSION

This study was initiated because of previous work in which an isolate of P. polymyxa protected A. thaliana against abiotic and pathogen stress under gnotobiotic conditions and in soil (48, 49). We describe here the successful tagging of P. polymyxa with a gfp-expressing plasmid and the pattern of colonization by this strain on the plant root.

GFP tagging has proven to be useful for localization studies in plant-microbe interactions (4, 16, 51). In an attempt to obtain stably tagged cells, we chose two P. polymyxa isolates, B1 and B2, previously reported to be PGPR (29-31, 48), and two plasmids, pBSVG101 and pCM20. Although both plasmids could be established in both strains, isolate B2 failed to exhibit measurable fluorescence. Control experiments showed that intact plasmids could be reisolated from transformants, indicating that inefficient expression rather than the absence of the gfp gene was responsible for the lack of fluorescence. Failure to detect fluorescence in bacteria containing a gfp gene driven by a promoter known to be active has been observed previously (26). Also, GFP-tagged cells of several bacterial species have been shown to vary significantly in fluorescence (6, 35, 50), possibly due to occasional incorrect folding of GFP or the formation of inclusion bodies (9). In addition, differences in physiological characteristics of natural isolates of the same species have been observed (27, 29-31), and such differences may reflect the selection of subpopulations of P. polymyxa by specific conditions in rhizosphere environments. Thus, although isolates B1 and B2 were indistinguishable on the basis of their 16S rRNA gene sequences, they behaved differently with respect to gfp expression, plasmid maintenance, and growth rate.

Isolate B1 showed fluorescence when it contained either of the two plasmids, pBSVG101 or pCM20. For the localization studies, P. polymyxa B1::pCM20 was chosen, since it showed wild-type-like growth characteristics, stable maintenance of the plasmid, and small cell-to-cell variations in fluorescence (Fig. 1B and 2). The gfp-tagged P. polymyxa B1::pCM20 strain was used for assessment of the localization of the bacteria on or in Arabidopsis roots. In order to avoid unsubstantiated conclusions, the bacterial interactions were studied in soil in addition to the previously established gnotobiotic system. For obvious reasons, gnotobiotic systems have advantages when detailed mechanistic studies are intended, since they minimize disturbances from uncontrolled environmental factors, but the results should be supported by analyses in more natural systems.

In both systems, colonization is initiated by bacterial accumulation at the root tip. Colonization of the natural isolate of P. polymyxa occurred in the form of a biofilm. Of relevance for the work described here, it has been reported that compared to highly subcultured B. subtilis laboratory strains, natural isolates generally form more robust biofilms (25). In the gnotobiotic system, biofilms formed around A. thaliana roots during the first few hours (Fig. 3A and 4A). In soil experiments, P. polymyxa also preferentially colonized regions around the root tip (Fig. 3D and E and 4B and D). The fact that in nonsterile soil experiments a P. polymyxa biofilm hindered indigenous bacterial colonization around the root tip indicates that this P. polymyxa isolate could be a potentially aggressive biocontrol agent for use against pathogens which colonize the root tip (Fig. 4D). P. polymyxa colonization progressed to the regions behind the root tip, although the organism occurred as single cells at much lower levels (Fig. 4E and F). It is known that exopolysaccharide secretion is regulated by quorum sensing (36). Thus, it is possible that due to an insufficient quorum of the bacteria in these regions, no compounds that formed an extracellular matrix were produced. If this is true, our model could provide a system to study quorum-sensing regulation in biofilm communities. Until now, quorum-sensing mechanisms have been studied in the context of planktonic cultures (36). In shaken cultures, all bacteria are in physiologically similar states and produce a signal at the same rate. Although this facilitates studies, it often fails to reflect the regulation of behavioral traits in complex microbial communication by quorum sensing. In the same regions, colonization by indigenous soil bacteria was also observed in nonsterile soil experiments (Fig. 4F). Root invasion by P. polymyxa started early in colonization, in the gnotobiotic system within the first few hours and in soil during the first few days (Fig. 5). This phenomenon could conceivably be related to the hydrolytic enzymes known to be produced by this bacterium (42). Based on these observations, we concluded that the pattern of colonization of P. polymyxa in the gnotobiotic system during the first 3 to 5 h essentially reflects the colonization in soil. After this time, differences in exudation from the roots in the liquid medium may affect the differences observed, such as a second region of biofilm formation in the root differentiation zone, the severity of damage seen on the root tissue, and the increase in bacteria in intercellular spaces in roots (Fig. 5).

We observed here that the colonization occurred mostly around the root tip. One of the most important factors that determines bacterial colonization on the plant root is root exudation (54, 55). Plant roots secrete a vast array of compounds into the rhizosphere. Exudation is heterogeneous in time and space (28). It also differs along the longitudinal axis from the base to the root tip, where the metabolic activity varies (17). The root cap is a source of hydrated polysaccharides sloughed from the root tip. These polysaccharides form the mucigel which lubricates the root during passage through the medium. Apoplastic sucrose could also diffuse from the root tip because of the concentration gradient. Sucrose does not leak from mature root sections since diffusion of this compound is blocked by the suberized layer of endodermal cells (23). Microorganisms that prefer this kind of nutrition might be attracted by these rich sources of nutrients.

The preferred colonization regions of the plant root observed here for P. polymyxa, both in a gnotobiotic system and in soil, are similar to those found for some endophytic bacteria (21). Even though P. polymyxa is generally considered a free-living rhizobacterium, bacterial cells were detected inside the root tissue outside the vascular cylinder, predominantly in intercellular spaces (Fig. 3C and 5). Entry into intact root tissue can be aided by hydrolytic enzymes (reference 39 and references therein) which are synthesized by P. polymyxa B1 and B2 (Timmusk, unpublished data). Endophytic bacteria, such as Azoarcus sp. (21), sometimes spread to aerial tissues. Reminiscent of some endophytic bacteria that have been investigated (45), P. polymyxa resides inside the plant root but does not spread to the leaves.

The observations reported here show that P. polymyxa has properties characteristic of PGPR but also properties characteristic of a DRB. Figure 3B indicates and Fig. 4B shows clearly that P. polymyxa affects root integrity, which in turn supports previous observations of dwarfed Arabidopsis plants with stunted root systems both in soil and in a gnotobiotic system (48, 49). Since both beneficial and harmful effects of P. polymyxa were seen previously under controlled gnotobiotic conditions (48) and natural conditions (49), it is clear that classification of this bacterium as a PGPR or a DRB is a matter of perspective. So far, comparative genomics indicates that it is not possible to distinguish between symbionts and pathogens at the genetic level. In their interactions with plants, both types of organisms use the same plant cell wall-degrading enzymes, phytohormones, and protein secretion mechanisms (for a review see reference 38). One problem lies in inadequate information; only a few fully sequenced genomes from plant-associated bacteria are available, and gram-negative bacteria have received most of the attention. In addition, endophytic unculturable bacteria have been almost neglected from this point of view. As shown by Buchnera aphidicola and Rickettsia prowazekii, evolution of endophytic symbiotic and parasitic bacteria results in both convergent and divergent changes (47). It has also been suggested that selection leads to the evolution of parasites with reduced virulence, and, accordingly, it has been speculated that some endophytes and symbionts could have evolved from parasites (38). Therefore, it might not be surprising that bacteria that are generally classified as beneficial can be deleterious under other circumstances. This duality could be the result of subtle alterations in gene regulation or horizontal gene transfer. For example, minor introduction of genomic DNA can convert a pathogen to a saprophyte and vice versa (20). Clearly, the effects of rhizobacteria on plants, from growth inhibition to growth promotion, can vary greatly depending on the experimental conditions. For example, inoculation with P. polymyxa strain L6-16R promoted growth of lodgepole pine in one location, inhibited it at a second site, and had no discernible effect at a third site (7). The mechanisms by which DRB sometimes promote plant growth (e.g., through protection from major pathogens or other stressful conditions) are poorly understood. How then can we reconcile deleterious and beneficial activities of P. polymyxa observed in the same plant host system? It is possible that the damage caused by the bacterium at the root tip ultimately results in activation of defense genes. This is in line with upregulation of the PR-1, ATVSP, and HEL genes, all of which are associated with biotic stress, and the drought-responsive gene ERD15 (48). A second possibility is that the P. polymyxa biofilm formed on the roots (Fig. 3A and 5A to D) coincides with the colonization sites of several pathogens and thereby functions as a protective layer to prevent access by the pathogens. The protection layer might also contribute to the plant-enhanced drought tolerance (48). In conclusion, whether (or when) the bacterial strain interacts with a host plant as a PGPR or a DRB is strongly dependent on the prevalent conditions, which may determine whether beneficial or deleterious aspects dominate.

We report here that P. polymyxa forms biofilms around the root tip and behaves as a root-invading bacterium and as a DRB under particular experimental conditions. As expected, due to the different environmental conditions, the population densities of both rhizosphere-colonizing and root-invading bacteria differ in the gnotobiotic and soil systems (Fig. 5). These results confirm that colonization by the bacterium can be modeled in the gnotobiotic system and that more detailed studies on biofilm formation can be performed using this model. Based on this study, niche exclusion and mechanical protection of the nonsuberized regions of roots will be pursued as a possible mechanism of P. polymyxa biocontrol and drought tolerance-enhancing activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linda Thomashow and her research group for advice and discussions. Jos Raaijmakers, Janet Jansson, and Eshel Ben Jacob are gratefully acknowledged for providing the P. fluorescens SS101, P. fluorescens A506::gfp2, and P. vortex strains. We are also indebted to Jos Raaijmakers for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by a grant from Stiftelsen Lantbruksforskning (to E.G.H.W.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bais, H. P., S. W. Park, F. R. Stermitz, K. M. Halligan, and J. M. Vivanco. 2002. Exudation of fluorescent beta-carbolines from Oxalis tuberosa L. roots. Phytochemistry 61:539-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bent, E., and C. P. Chanway. 2002. Potential for misidentification of a spore-forming Paenibacillus polymyxa isolate as an endophyte by using culture-based methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:4650-4652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bezzate, S., S. Aymerich, R. Chambert, S. Czarnes, O. Berge, and T. Heulin. 2000. Disruption of the Paenibacillus polymyxa levansucrase gene impairs its ability to aggregate soil in the wheat rhizosphere. Environ. Microbiol. 2:333-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloemberg, G. V., G. A. O'Toole, B. J. Lugtenberg, and R. Kolter. 1997. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for Pseudomonas spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4543-4551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolwerk, A., A. L. Lagopodi, A. H. Wijfjes, G. E. Lamers, A. W. T. F. Chin, B. J. Lugtenberg, and G. V. Bloemberg. 2003. Interactions in the tomato rhizosphere of two Pseudomonas biocontrol strains with the phytopathogenic fungus Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-lycopersici. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 16:983-993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burlage, R. S., Z. K. Yang, and T. Mehlhorn. 1996. A transposon for green fluorescent protein transcriptional fusions: application for bacterial transport experiments. Gene 173:53-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chanway, C. P., and F. B. Holl. 1994. Growth of outplanted lodgepole pine seedlings one year after inoculation with plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. For. Sci. 40:238-246. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen, I., I. G. Ron, and E. Ben Jacob. 2000. From branching to nebula patterning during colonial development of the Paenibacillus alvei bacteria. Physica A 286:321-326. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cormack, B. P., R. H. Valdivia, and S. Falkow. 1996. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP). Gene 173:33-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costerton, J. W. 1995. Overview of microbial biofilms. J. Ind. Microbiol. 15:137-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davey, M. E., and A. G. O'Toole. 2000. Microbial biofilms: from ecology to molecular genetics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol Rev. 64:847-867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Souza, J. T., M. de Boer, P. de Waard, T. A. van Beck, and J. M. Raaijmakers. 2003. Biochemical, genetic, and zoosporicidal properties of cyclic lipopeptide surfactants produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:7161-7172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drews, G. N., J. L. Bowman, and E. M. Meyerowitz. 1991. Negative regulation of the Arabidopsis homeotic gene AGAMOUS by the APETALA2 product. Cell 65:991-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emmert, E. A. B., and J. Handelsman. 1999. Biocontrol of plant disease: a (Gram-) positive perspective. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 171:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gamalero, E., G. Lingua, G. Berta, and P. Lemanceau. 2003. Methods for studying root colonization by introduced beneficial bacteria. Agronomie 23:407-418. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gau, A. E., C. Dietrich, and K. Kloppstech. 2002. Non-invasive determination of plant-associated bacteria in the phyllosphere of plants. Environ. Microbiol. 4:744-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilroy, S., and D. L. Jones. 2000. Through form to function: root hair development and nutrient uptake. Trends Plant Sci. 5:56-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holl, F. B., and C. P. Chanway. 1992. Rhizosphere colonization and seedling growth promotion of lodgepole pine by Bacillus polymyxa. Can. J. Microbiol. 38:303-308. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holl, F. B., C. P. Chanway, R. Turkington, and R. A. Radley. 1988. Response of crested wheatgrass (Agropyron cristatum L.), perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) and white clover (Trifolium repens L.) to inoculation with Bacillus polymyxa. Soil Biol. Biochem. 20:19-24. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsia, R. C., Y. Pannekoek, E. Ingerowski, and P. M. Bavoil. 1997. Type III secretion genes identify a putative virulence locus of Chlamydia. Mol. Microbiol. 25:351-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurek, T., B. Reinhold-Hurek, M. van Montagu, and E. Kellenberger. 1994. Root colonization and systemic spreading of Azoarcus sp. strain BH72 in grasses. J. Bacteriol. 176:1913-1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itaya, M., S. M. Shaheduzzaman, K. Matsui, A. Omori, and T. Tsuji. 2001. Green marker for colonies of Bacillus subtilis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 65:579-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaeger, C. H., S. E. Lindow, W. Miller, E. Clark, and M. K. Firestone. 1999. Mapping of sugar and amino acid availability in soil around roots with bacterial sensors of sucrose and tryptophan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2685-2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kajimura, Y., and M. Kaneda. 1996. Fusaricidin A, a new depsipeptide antibiotic produced by Bacillus polymyxa KT-8. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation, structure elucidation, and biological activity. J. Antibiot. 49:129-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kinsinger, R. F., M. C. Shirk, and R. Fall. 2003. Rapid surface motility in Bacillus subtilis is dependent on extracellular surfactin and potassium ion. J. Bacteriol. 185:5627-5631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kremer, L., A. Baulard, J. Estaquier, O. Poulain-Godefroy, and C. Locht. 1995. Green fluorescent protein as a new expression marker in mycobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 17:913-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lebuhn, M., T. Heulin, and A. Hartmann. 1997. Production of auxin and other indolic and phenolic compounds by Paenibacillus polymyxa strains isolated from different proximity to plant roots. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 22:325-334. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao, H., G. Rubio, X. Yan, A. Cao, K. M. Brown, and J. P. Lynch. 2001. Effect of phosphorus availability on basal root shallowness in common bean. Plant Soil 232:69-79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindberg, T., and U. Granhall. 1986. Acetylene reduction in gnotobiotic cultures with rhizosphere bacteria and wheat. Plant Soil 92:171-180. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindberg, T., and U. Granhall. 1984. Isolation and characterization of dinitrogen-fixing bacteria from the rhizosphere of temperate cereals and forage grasses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48:683-689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindberg, T., U. Granhall, and K. Tomenius. 1985. Infectivity and acetylene reduction of diazotrophic rhizosphere bacteria in wheat (Triticum aestivum) seedlings under gnotobiotic conditions. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1:123-129. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luchansky, J. B., P. M. Muriana, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1988. Application of electroporation for transfer of plasmid DNA to Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, Listeria, Pediococcus, Bacillus, Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, and Propionibacterium. Mol. Microbiol. 2:637-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 34.Murashige, T., and F. Skoog. 1962. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol. Plant. 15:473-497. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olofsson, A. C., A. Zita, and M. Hermansson. 1998. Floc stability and adhesion of green-fluorescent-protein-marked bacteria to flocs in activated sludge. Microbiology 144:519-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parsek, M. R., and E. P. Greenberg. 2005. Sociomicrobiology: the connections between quorum sensing and biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 13:27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petersen, D. J., M. Srinivasan, and C. P. Chanway. 1996. Bacillus polymyxa stimulates increased Rhizobium etli populations and nodulation when co-resident in the rhizosphere of Phaseolus vulgaris. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 142:271-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Preston, G. M., B. Haubold, and P. B. Rainey. 1998. Bacterial genomics and adaptation to life on plants: implications for the evolution of pathogenicity and symbiosis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1:589-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quadt-Hallmann, A., and J. W. Kloepper. 1997. Bacterial endophytes in cotton: mechanisms of entering the plant. Can. J. Microbiol. 43:557-582. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raaijmakers, J. M., M. Leeman, M. M. P. van Oorschot, I. van der Siuls, B. Schippers, and P. A. H. M. Bakker. 1995. Dose-response relationships of biological control of Fusarium wilt of radish by Pseudomonas spp. Phytopathology 85:1075-1081. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosado, A. S., G. F. Duarte, and L. Seldin. 1994. Optimization of electroporation procedure to transform B. polymyxa SCE2 and other nitrogen-fixing Bacillus. J. Microbiol. Methods 19:1-11. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanz-Aparicio, J., J. A. Hermoso, M. Martinez-Ripoll, J. L. Lequerica, and J. Polaina. 1998. Crystal structure of beta-glucosidase A from Bacillus polymyxa: insights into the catalytic activity in family 1 glycosyl hydrolases. J. Mol. Biol. 275:491-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shishido, M., H. B. Massicotte, and C. P. Chanway. 1996. Effect of plant growth promoting Bacillus strains on pine and spruce seedling growth and mycorrhizal infection. Ann. Bot. 77:433-441. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smyth, D. R., J. L. Bowman, and E. M. Meyerowitz. 1990. Early flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2:755-767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sturz, A. V., B. R. Christie, and J. Nowak. 2000. Bacterial endophytes, potential role in developing sustainable systems of crop production. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 19:1-30. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suslow, T. V., and M. N. Schroth. 1982. Role of deleterious rhizobacteria as minor pathogens in reducing crop growth. Phytopathology 72:111-115. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamas, I., L. M. Klasson, J. P. Sandström, and S. G. E. Andersson. 2001. Mutualists and parasites: how to paint yourself into a (metabolic) corner. FEBS Lett. 498:135-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Timmusk, S., and E. G. H. Wagner. 1999. The plant-growth-promoting rhizobacterium Paenibacillus polymyxa induces changes in Arabidopsis thaliana gene expression: a possible connection between biotic and abiotic stress responses. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 12:951-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Timmusk, S., P. van West, N. A. R. Gow, and E. G. H. Wagner. 2003. Antagonistic effects of Paenibacillus polymyxa towards the oomycete plant pathogens Phytophthora palmivora and Pythium aphanidermatum, p. 1-28. In Mechanism of action of the plant growth promoting bacterium Paenibacillus polymyxa. Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

- 50.Tombolini, R., A. Unge, M. E. Davey, F. K. Bruijn, and J. K. Jansson. 1997. Flow cytometric and microscopic analysis of GFP-tagged Pseudomonas fluorescens bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 22:17-28. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tombolini, R., D. J. van der Gaag, B. Gerhardson, and J. K. Jansson. 1999. Colonization pattern of the biocontrol strain Pseudomonas chlororaphis MA 342 on barley seeds visualized by using green fluorescent protein. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3674-3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Unge, A., R. Tombolini, A. Moller, and J. K. Jansson. 1996. Optimization of gfp as a marker for detection of bacteria in environmental samples, p 391-394. In J. W. Hastings, L. J. Kricka, and P. E. Stanley (ed.), Bioluminescence and chemoluminescence: molecular reporting with photons. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 53.von der Weid, I., E. Paiva, A. Nobrega, J. D. van Elsas, and L. Seldin. 2000. Diversity of Paenibacillus polymyxa strains isolated from the rhizosphere of maize planted in Cerrado soil. Res. Microbiol. 151:369-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walker, T. S., H. P. Bais, E. Grotewold, and J. M. Vivanco. 2003. Root exudation and rhizosphere biology. Plant Physiol. 132:44-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weller, D. M., and L. S. Thomashow. 1994. Current challenges in introducing beneficial microorganisms into the rhizosphere, p. 1-18. In F. O'Gara, D. N. Dowling, and B. Boesten (ed.), Molecular ecology of rhizosphere microorganisms. VCH, Weinheim, Germany.