Abstract

Streptococcus mutans UA159, the genome sequence reference strain, exhibits nonlantibiotic mutacin activity. In this study, bioinformatic and mutational analyses were employed to demonstrate that the antimicrobial repertoire of strain UA159 includes mutacin IV (specified by the nlm locus) and a newly identified bacteriocin, mutacin V (encoded by SMU.1914c).

Bacteriocins are antibacterial proteins produced by bacteria that kill or inhibit the growth of closely related strains, and their biogenesis is thought to modulate the growth of competitor organisms occupying the same microecological niche (12). The bacteriocins produced by the oral bacterium Streptococcus mutans are termed mutacins and are divided into two groups: (i) the lanthionine-containing (lantibiotic) mutacins (6, 11, 16, 19, 20) and (ii) the unmodified mutacins (2, 21). While most bacteriocin activities characterized to date consist of a single active polypeptide, several two-component lantibiotic and nonlantibiotic bacteriocins have also been described, and these are dependent upon the collaborative activity of two polypeptides to exert their full antimicrobial activity (7, 9, 14, 15, 17, 23). Although in most cases both peptides act synergistically to effect target cell death, exceptions have been noted. For example, in the case of thermophilin 13, ThmB (which has no apparent intrinsic inhibitory activity of its own) functions to enhance the antibacterial activity of ThmA (14).

Mutacin IV is a putative two-component bacteriocin that is composed of the peptides NlmA* and NlmB*, both of which are generated by the posttranslational removal of a signal peptide from their respective prepeptides NlmA and NlmB (encoded by nlmA and nlmB, respectively [21]). However, the contribution of each peptide to mutacin IV activity has not been definitively established, since NlmA* and NlmB* have not yet been separately purified (21). Although mutacin IV was originally characterized from S. mutans UA140, the nlmAB locus (SMU.150 and SMU.151 for nlmA and nlmB, respectively) was identified in the genome reference strain UA159, although its function has not been assigned (21). Despite previous reports that strain UA159 is nonbacteriocinogenic (1, 5), we have found that this strain (kindly provided by J. Novak [University of Alabama—Birmingham]) readily exhibits antimicrobial activity when tested using a deferred antagonism protocol (2) against a panel of 84 indicator bacteria consisting of 74 streptococcal strains (belonging to nine distinct species) of human (oral) and animal origin, eight strains of Lactococcus lactis, and two strains of Micrococcus luteus (Table 1). On the other hand, S. mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus indicator strains were not inhibited by UA159 (Table 1), an observation consistent with previous findings (5; J. D. F. Hale and J. R. Tagg, unpublished data). The presence of the nlmAB locus and absence of any intact operons encoding lantibiotic mutacins in strain UA159 (1), together with its ability to inhibit the growth of three strains (Streptococcus sanguinis ATCC 10556, Streptococcus oralis ATCC 10557 and Streptococcus gordonii ATCC 10558) (Table 1) previously used as mutacin IV indicators (21), led us to speculate that the inhibitory activity of this strain is, at least in part, due to mutacin IV. Therefore, the initial aim of our investigation was to use genetic dissection to establish whether the nlmAB locus is functional in strain UA159 and, if so, to define the individual roles of NlmA* and NlmB* in mutacin IV activity.

TABLE 1.

Inhibitory spectra of S. mutans UA159 and its mutants

| Indicator bacteria (no. of strains tested)a | No. of indicator strains inhibited by:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UA159 | UAΔNlmTb | UAΔNlmA | UAΔNlmB | UAΔNlmAB | UAΔ (281/283) | UAΔ423 | UAΔ1892 | UAΔ (1895/1896) | UAΔ (1905/1906) | UAΔ1914 | UAΔ (1914/NlmAB) | |

| Streptococcus constellatus (10) | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| Streptococcus gordonii (7) | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 0 |

| “Streptococcus milleri” (3) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes (10) | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| Streptococcus salivarius (10) | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| Streptococcus sanguinis (5) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Streptococcus uberis (10) | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| Streptococcus mitis batch A (6) | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| Streptococcus oralis batch A (5) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Lactococcus lactis (8) | 8 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Micrococcus luteus (2) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| S. mitis batch B (3) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| S. oralis batch B (2) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| S. mitis SK648 (1) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| S. oralis strains OB717 and OB718 (2) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| S. mutans (2) | 0 | NTc | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| Streptococcus sobrinus (1) | 0 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

S. mitis and S. oralis strains are divided into batches depending on their mutacin sensitivities (see text).

Strain UAΔNlmT (10) was used as the null mutant (negative control) for all deferred antagonism assays.

NT, not tested.

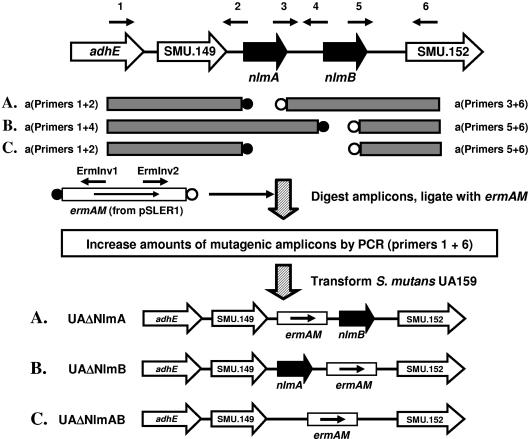

Appropriate nlm mutants of S. mutans strain UA159 were generated by replacing either nlmA, nlmB, or the nlmAB locus with the erythromycin resistance determinant ermAM (3) using a PCR ligation mutagenesis strategy (13) (Fig. 1) with the following modifications: (i) inclusion of an additional PCR step to generate more of each mutagenic construct prior to transformation, (ii) the use of fetal calf serum in place of horse serum in the transformation medium, and (iii) selection of transformants on brain heart infusion agar (Becton Dickinson) containing 0.5% (wt/vol) yeast extract and 2.5 μg/ml erythromycin. All PCR primers (Invitrogen Corp., Auckland, New Zealand) used in this study are listed in Table 2. ermAM, which lacks a transcription terminator at its 3′ end, was inserted in the same transcriptional orientation as the gene of interest (Fig. 1), thus precluding any polar effects. The presence of the desired mutations in selected erythromycin-resistant transformants was verified by sequencing of the PCR products generated using appropriate nlm- or ermAM-specific primers (Table 2) and by Southern hybridization experiments (22).

FIG. 1.

Allelic replacement, by PCR ligation mutagenesis (13), of genes (nlmAB) encoding the peptides comprising mutacin IV. Other putative bacteriocin-encoding genes investigated in this study (see Fig. 2) were also inactivated using this strategy. For clarity, the loci are not drawn to scale. The PCR primers shown are numbered as follows: 1, NlmABUpF; 2, NlmAUpR; 3, NlmADwF; 4, NlmBUpR; 5, NlmBDwF; 6, NlmABDwR. The filled and unfilled circles refer to EcoRI and PstI restriction sites, respectively. The source of ermAM was pSLER1 (pSL1190 [4] containing ermAM cloned into the NdeI site; laboratory collection) and ermAM was always inserted in the same transcriptional orientation as the gene of interest. The locations of the ErmInv PCR primers used to confirm each mutation are also shown. adhE, putative alcohol-acetaldehyde dehydrogenase; nlmA and nlmB, prepeptides of NlmA* and NlmB*, respectively; SMU.149, putative transposase; SMU.152, hypothetical protein.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used in this study

| Primer | Nucleotide sequence (5′-3′)a | Location of primer (nucleotides) |

|---|---|---|

| NlmABUpF | CCACGTCAGCCTTACATTGAAGAGATGAAGC | 7676-7706 |

| NlmAUpR | AAAAGAATTCCATCAAATTGTTCAAATGCCTGTGTATCCA | 8754-8783 |

| NlmADwFb | AAAACTGCAGGGCACTTGGGGACTCATTCGATCTCATTAAA | 8927-8957 |

| NlmBUpRb | AAAAGAATTCTTTAATTCCATGGTATTAATTCTCCATTCC | 8967-8996 |

| NlmBUpF | CGATCTGCAGGAGTTGGTGCGGTTGGATCTGTAGTTTTTCC | 9164-9194 |

| NlmABDwR | GGCCCAACGCAAAATCTTTGTGGAGATACG | 9411-9440 |

| Smu283UpF | TTCCTGTTGCTTATCTTGCTGGTTT | 117-141 |

| Smu283UpR | GCAGGAATTCTTCTCCTGCTGTTTCAAA | 759-784 |

| Smu283DwF | GGTGCTGCAGTTATTTATTATGGCG | 2259-2283 |

| Smu283DwR | CCCATTATTACAAAAACTGGAAGCAAAC | 2798-2825 |

| Smu423UpF | CAGAAGATGAGCGAATGAAGTGAGC | 57-81 |

| Smu423UpR | CATACCCCCTAGAATTCCTAAACCTG | 1089-1114 |

| Smu423DwF | CGGCTGCAGGAGGCTTGGTCTGG | 1161-1182 |

| Smu423DwR | AGCGGCATCGTAATCTATCGTCAT | 2167-2190 |

| Smu1892UpF | TGGTTTGGAGGCTCGTATTCGTC | 3701-3723 |

| Smu1892UpR | CGTTTCCAGAATTCAGTTTGTGTTTT | 2978-3003 |

| Smu1892DwF | GCAGCTGCAGGCTAATAAAAATCTGAGTTGCTGTAA | 2782-2807 |

| Smu1892DwR | CCAAGGAATAGTAAAAATGGAATAAGG | 2193-2219 |

| Smu1895UpF | TCGCAAGTGAGCTAATGAATAATCCG | 5582-5607 |

| Smu1895UpR | ACCTAAAGCGCCTGTTCGAATTCGTA | 4894-4918 |

| Smu1895DwF | GTTGGTGCAACTGCAGGATCTTTTTAC | 4622-4648 |

| Smu1895DwR | CTTTTGACCGCTTGCTGGAATGGC | 3558-3581 |

| Smu1905UpF | AACTTTTTGGGTGCAGGTCAGAA | 1791-1813 |

| Smu1905UpR | TCGGCTGAATTCCAACTACATCC | 747-769 |

| Smu1905DwF | TGTGGGAACTAGTATTTATGATGG | 347-370 |

| Smu1905DwR | CGGCCAATATATAAGGTATAGCTGTTTTC | 9877-9905 |

| Smu1914UpF | TAGTTTTATCTTCTCATCCACGACA | 5797-5821 |

| Smu1914UpR | GAAAGTGAATTCATTATCCATTACG | 5243-5266 |

| Smu1914DwF | CTTTGGGGCTATTGCTGCAGGAA | 5094-5116 |

| Smu1914DwR | CATGCTTTTCTATGCGGTCTATTGA | 4029-4053 |

| ErmInv1 | CCAGTTCGCGTTAAATGCCCTTTACCTG | 374-403 |

| ErmInv2 | CTTACCCGCCATACCACAGATGTTCCAGAT | 784-813 |

| KanF | GATAAACCCAGCGAATTCATTTGAGGTGATAGGTAAG | 1-36 |

| KanR | TCGATACAAATTCCTCTGCAGGCGCTCTAGACCCCTATC | 1451-1488 |

The Nlmx, Smu283x, Smu1892x/1895x (including Smu1905DwR), Smu1905x/1914x, ErmInv, and Kan primers were designed based on sequences with GenBank accession numbers AE014866, AE014877, AE015015, AE015016, Y00116, and V01547, respectively. Restriction sites for EcoRI (GAATTC), PstI (CTGCAG), or SpeI (ACTAGT) incorporated into the primer are underlined.

The partners for the NlmADwF and NlmBUpR primers during PCR are NlmABDwR and NlmABUpF, respectively.

In order to determine the functions of NlmA* and NlmB* in mutacin IV activity, mutants of strain UA159 containing individually disrupted nlmA (UAΔNlmA) or nlmB (UAΔNlmB) were constructed (Fig. 1). When both mutants were assayed for activity against the panel of 84 mutacin-sensitive indicator bacteria, growth inhibition of 66 strains (comprising all strains of S. constellatus, S. gordonii, S. milleri, S. pyogenes, S. salivarius, S. sanguinis, and S. uberis, as well as 6 [of 10] S. mitis strains and 5 [of 9] S. oralis strains) was dependent upon a functional nlmA gene (Table 1). In contrast, inactivation of nlmB did not appear to affect inhibitory activity against the same 66 strains (Table 1). The above observations were corroborated when selected strains were tested by a modification of the standard deferred antagonism assay (2) in which the number of producer cells inoculated was standardized (15-μl drop inoculum of an 18-h Todd-Hewitt broth culture adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.02). No significant differences in the sizes of inhibitory zones were detected between wild-type UA159 and the nlmB mutant UAΔNlmB (Table 3). Taken collectively, our results demonstrate that the nlm locus is functional in S. mutans UA159 but also cast some doubt as to whether mutacin IV is a bona fide two-component bacteriocin. However, it is also possible that the range of indicator strains selected for this study may not have been sufficiently diverse to detect any effects conferred by NlmB*.

TABLE 3.

Drop inoculum deferred antagonism assay for S. mutans UA159 and its nlm mutants

| Indicator strain | Inhibitory zone diameter (mm)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | UAΔNlmA | UAΔNlmB | UAΔNlmAB | |

| S. gordonii C219 | 22 | 0 | 21 | 0 |

| S. milleri NCTC 10708 | 28 | 0 | 27 | 0 |

| S. mitis OB714 | 24 | 0 | 24 | 0 |

| S. salivarius 20P3 | 15 | 0 | 15 | 0 |

| S. uberis ATCC 27958 | 21 | 0 | 20 | 0 |

Aliquots (15 μl) of each producer strain were deposited as drop inocula (11-mm diameter) on the surface of the mutacin test medium (2).

Interestingly, growth of 18 of the 84 indicator strains (all eight L. lactis, both M. luteus, four S. mitis and four S. oralis) did not appear to be affected by the individual inactivation of either nlmA or nlmB (Table 1). This raises the possibilities that either (i) each individual peptide possesses inhibitory activity against these strains or (ii) additional inhibitory agents (unrelated to mutacin IV) are produced by strain UA159. To resolve this unexpected finding, strain UAΔNlmAB was generated in which the entire nlmAB locus was deleted (Fig. 1). No loss of inhibitory activity was detected against any of these 18 indicator bacteria (Table 1), indicating that the antimicrobial repertoire of strain UA159 extends beyond what is attributable to mutacin IV.

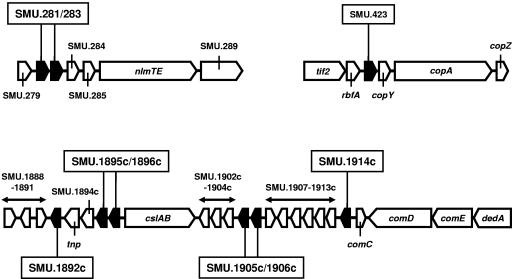

We have recently reported that nonlantibiotic mutacin biogenesis in strain UA159 requires the ABC transporter NlmTE (10). Furthermore, a search of the UA159 genome sequence revealed several loci (Fig. 2) encoding hypothetical peptides, each possessing a double-glycine-type leader sequence similar to that of NlmA (10). This implies that these peptides could be exported by NlmTE and would therefore be candidates for the additional observed antibacterial activities. Nine potential mutacin-encoding genes (SMU.281, SMU.283, SMU.423, SMU.1892c, SMU.1895c, SMU.1896c, SMU.1905c, SMU.1906c, and SMU.1914c) (Fig. 2) were replaced with ermAM, either individually or in pairs, to yield the six mutants UAΔ(281/283), UAΔ423, UAΔ1892, UAΔ(1895/1896), UAΔ(1905/1906), and UAΔ1914, respectively. When tested against the 18 indicator strains that are not sensitive to mutacin IV, loss of inhibitory activity against all but three strains (S. mitis SK648, and S. oralis strains OB717 and OB718) was only observed with the SMU.1914c mutant, UAΔ1914 (Table 1). As expected, a double-knockout mutant of UAΔ1914, strain UAΔ(1914/NlmAB), in which the nlmAB locus was replaced with the kanamycin resistance (600 μg/ml) determinant aphA3 (24), exhibited the combined inhibitory spectra of both UAΔNlmAB and UAΔ1914 (Table 1). Thus, SMU.1914c appears to encode an additional novel mutacin. In order to maintain consistency in the nomenclature of mutacins, we propose that SMU.1914c be designated nlmC and its gene product be named mutacin V.

FIG. 2.

Genomic organization of the open reading frames (ORFs; filled pentagons) encoding potential nonlantibiotic mutacins investigated in this study. For simplicity, the loci are not drawn to scale. ORFs designated by their GenBank locus tags (e.g., SMU.283) encode hypothetical proteins. Note that SMU.282 does not exist. The translational orientation of each ORF is also indicated. nlmTE, ABC transporter required for export of nonlantibiotic mutacins (10); tif2, translation initiation factor 2; rbfA, ribosome binding factor A; copY, putative transcriptional regulator; copAZ, components of a copper transport system; tnp, putative transposase of ISSmu1 (1); cslAB, ABC transport system required for natural transformation (10, 18); comCDE, signal transduction system essential for development of natural competence (8); dedA, putative membrane-associated protein.

In conclusion, we have used bioinformatic and mutational analyses to show that S. mutans UA159 produces (i) a known bacteriocin, mutacin IV, which is a major contributor to the antimicrobial spectrum of the strain, and (ii) a newly identified antimicrobial agent, mutacin V, which is mainly active against nonstreptococcal targets. However, an additional inhibitory agent(s) active against certain S. mitis and S. oralis strains could not be identified using our existing experimental strategy. Furthermore, genetic dissection of the nlmAB locus does not support the hypothesis that mutacin IV is a two-component mutacin and thus the role, if any, of NlmB* remains enigmatic. Clearly, S. mutans is a prodigious producer of mutacins, a deeper understanding of which may help elucidate how this oral pathogen establishes in the oral cavity.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Novak (University of Alabama—Birmingham), A. Holmes (Department of Oral Sciences, University of Otago), and M. Kilian (University of Aarhus) for provision of bacterial strains and D. Cvitkovitch (University of Toronto) for the gift of synthetic competence-stimulating peptide.

This study was supported by the Health Research Council of New Zealand and the Otago Medical Research Foundation. J.D.F.H. was a recipient of a University of Otago Postgraduate Scholarship. Y.-T.T. was a University of Otago Oral Microbiology and Dental Health Theme Summer Student.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ajdic, D., W. M. McShan, R. E. McLaughlin, G. Savic, J. Chang, M. B. Carson, C. Primeaux, R. Tian, S. K. Kenton, H. Jia, S. Lin, Y. Qian, S. Li, H. Zhu, F. Najar, H. Lai, J. White, B. A. Roe, and J. J. Ferretti. 2002. Genome sequence of Streptococcus mutans UA159, a cariogenic dental pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:14434-14439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balakrishnan, M., R. S. Simmonds, A. Carne, and J. R. Tagg. 2000. Streptococcus mutans strain N produces a novel low molecular mass non-lantibiotic bacteriocin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 183:165-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brehm, J., G. Salmond, and N. Minton. 1987. Sequence of the adenine methylase gene of the Streptococcus faecalis plasmid pAMb1. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brosius, J. 1989. Superpolylinkers in cloning and expression vectors. DNA 8:759-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, P., F. Qi, J. Novak, and P. W. Caufield. 1999. The specific genes for lantibiotic mutacin II biosynthesis in Streptococcus mutans T8 are clustered and can be transferred en bloc. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1356-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chikindas, M. L., J. Novak, A. J. Driessen, W. N. Konings, K. M. Schilling, and P. W. Caufield. 1995. Mutacin II, a bactericidal antibiotic from Streptococcus mutans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2656-2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuozzo, S. A., P. Castellano, F. J. Sesma, G. M. Vignolo, and R. R. Raya. 2003. Differential roles of the two-component peptides of lactocin 705 in antimicrobial activity. Curr. Microbiol. 46:180-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cvitkovitch, D. G., Y. H. Li, and R. P. Ellen. 2003. Quorum sensing and biofilm formation in streptococcal infections. J. Clin. Investig. 112:1626-1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garneau, S., N. I. Martin, and J. C. Vederas. 2002. Two-peptide bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. Biochimie 84:577-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hale, J. D. F., N. C. K. Heng, R. W. Jack, and J. R. Tagg. 2005. Identification of nlmTE, the locus encoding the ABC transport system required for export of nonlantibiotic mutacins in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 187:5036-5039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hillman, J. D., J. Novak, E. Sagura, J. A. Gutierrez, T. A. Brooks, P. J. Crowley, M. Hess, A. Azizi, K. Leung, D. Cvitkovitch, and A. S. Bleiweis. 1998. Genetic and biochemical analysis of mutacin 1140, a lantibiotic from Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 44:141-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jack, R. W., J. R. Tagg, and B. Ray. 1995. Bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 59:171-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau, P. C., C. K. Sung, J. H. Lee, D. A. Morrison, and D. G. Cvitkovitch. 2002. PCR ligation mutagenesis in transformable streptococci: application and efficiency. J. Microbiol. Methods 49:193-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marciset, O., M. C. Jeronimus-Stratingh, B. Mollet, and B. Poolman. 1997. Thermophilin 13, a nontypical antilisterial poration complex bacteriocin, that functions without a receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 272:14277-14284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin N. I., T. Sprules, M. R. Carpenter, P. D. Cotter, C. Hill, R. P. Ross, and J. C. Vederas. 2004. Structural characterization of lacticin 3147, a two-peptide lantibiotic with synergistic activity. Biochemistry 43:3049-3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mota-Meira, M., C. Lacroix, G. LaPointe, and M. C. Lavoie. 1997. Purification and structure of mutacin B-Ny266: a new lantibiotic produced by Streptococcus mutans. FEBS Lett. 410:275-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navaratna, M. A., H. G. Sahl, and J. R. Tagg. 1998. Two-component anti-Staphylococcus aureus lantibiotic activity produced by Staphylococcus aureus C55. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4803-4808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petersen, F. C., and A. A. Scheie. 2000. Genetic transformation in Streptococcus mutans requires a peptide secretion-like apparatus. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 15:329-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qi, F., P. Chen, and P. W. Caufield. 1999. Purification of mutacin III from group III Streptococcus mutans UA787 and genetic analyses of mutacin III biosynthesis genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3880-3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qi, F., P. Chen, and P. W. Caufield. 2000. Purification and biochemical characterization of mutacin I from the group I strain of Streptococcus mutans, CH43, and genetic analysis of mutacin I biosynthesis genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3221-3229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi, F., P. Chen, and P. W. Caufield. 2001. The group I strain of Streptococcus mutans, UA140, produces both the lantibiotic mutacin I and a nonlantibiotic bacteriocin, mutacin IV. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:15-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 23.Stephens, S. K., B. Floriano, D. P. Cathcart, S. A. Bayley, V. F. Witt, R. Jimenez-Diaz, P. J. Warner, and J. L. Ruiz-Barba. 1998. Molecular analysis of the locus responsible for production of plantaricin S, a two-peptide bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus plantarum LPCO10. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1871-1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trieu-Cuot, P., and P. Courvalin. 1983. Nucleotide sequence of the Streptococcus faecalis plasmid gene encoding the 3′5"-aminoglycoside phosphotransferase type III. Gene 23:331-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]