Abstract

Arthrobacter chlorophenolicus A6, a previously described 4-chlorophenol-degrading strain, was found to degrade 4-chlorophenol via hydroxyquinol, which is a novel route for aerobic microbial degradation of this compound. In addition, 10 open reading frames exhibiting sequence similarity to genes encoding enzymes involved in chlorophenol degradation were cloned and designated part of a chlorophenol degradation gene cluster (cph genes). Several of the open reading frames appeared to encode enzymes with similar functions; these open reading frames included two genes, cphA-I and cphA-II, which were shown to encode functional hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenases. Disruption of the cphA-I gene yielded a mutant that exhibited negligible growth on 4-chlorophenol, thereby linking the cph gene cluster to functional catabolism of 4-chlorophenol in A. chlorophenolicus A6. The presence of a resolvase pseudogene in the cph gene cluster together with analyses of the G+C content and codon bias of flanking genes suggested that horizontal gene transfer was involved in assembly of the gene cluster during evolution of the ability of the strain to grow on 4-chlorophenol.

Arthrobacter chlorophenolicus A6 is a gram-positive actinobacterium that was previously isolated from a soil slurry enriched with increasing concentrations of 4-chlorophenol (4-CP) (28). This bacterium can degrade unusually high concentrations of 4-CP (up to 2.7 mM) and other p-substituted phenols, such as 4-nitrophenol and 4-bromophenol (28). In addition, A. chlorophenolicus A6 can degrade 4-CP at low temperatures (5°C) and during temperature fluctuations between 28°C and 5°C (3). Strain A6 was previously tagged with marker genes encoding the green fluorescent protein (gfp) or firefly luciferase (luc) in order to specifically monitor its ability to survive in nonsterile soil as it degraded 4-CP (9). The tagged cells survived well and were metabolically active in soil contaminated with 4-CP (9, 12). A larger fraction of the cell population remained viable after incubation in soil at 5°C than after incubation in soil at 28°C (4).

There have been several reports of 4-CP degradation in other bacteria, but none of these bacteria have been shown to degrade concentrations of 4-CP as high as those degraded by A. chlorophenolicus A6. Successful mineralization of 4-CP by bacteria is usually accomplished by the oxidation of 4-CP to 4-chlorocatechol, followed by ortho cleavage of the aromatic ring. After ring cleavage, the chlorine is removed and the carbon skeleton is transformed into products that are assimilated into the central metabolism of the cell. By contrast, two strains belonging to the actinobacterium group, Arthrobacter ureafaciens CPR706 (5) and Nocardioides sp. strain NSP41 (8), were reported to transform 4-CP into hydroquinone instead of 4-chlorocatechol. However, the degradation pathways in these strains have not been described further.

The aim of the present study was to elucidate the biochemistry and genetics of 4-chlorophenol degradation in A. chlorophenolicus A6. Our results suggest that hydroxyquinol is an intermediate in the 4-CP degradation route used by A. chlorophenolicus A6, a possibility which has not been reported previously for aerobic degradation of monosubstituted chlorophenols by bacteria. In addition, we identified a 4-CP catabolic gene cluster in this strain and constructed a mutant in which one of the key catabolic genes was interrupted in order to address its functional significance. The results of this study increase our understanding of the diversity and evolution of catabolic pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture conditions.

A minimal medium (GM medium) was used for growth of A. chlorophenolicus A6 on 4-CP as described previously (28). 4-CP was added to a concentration of 1.2 or 1.9 mM, the cultures were incubated at 28°C, and the cells were normally harvested at the mid-log phase, at which time the cultures had an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1. When higher cell densities were desired, yeast extract was added to GM medium to a final concentration of 0.1% (wt/vol), or 10% Luria-Bertani broth (LB) was used. Escherichia coli was grown in LB or on LB agar plates at 37°C. When appropriate, ampicillin was added to a concentration of 50 μg/ml, chloramphenicol was added to a concentration of 34 μg/ml, or 2,2′-dipyridyl was added to a concentration of 1 mM.

Chloride ion measurements.

A. chlorophenolicus A6 cells were grown in GM medium with 1.9 mM 4-CP to the stationary phase and inoculated into fresh medium to an OD600 of approximately 0.04. Then 4-CP was added at different concentrations up to an inhibitory level of 3.5 mM to three 100-ml replicate cultures for each concentration, and the cultures were incubated at 28°C with shaking. The 4-CP concentration was measured in cell-free supernatants at 279 nm with a spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). The chloride ion concentration was measured with an ion-selective electrode (Orion Research Inc., Beverly, MA), and prior to every measurement the accuracy of the electrode was confirmed by comparison to a standard curve.

Gas chromatography.

Samples (5 ml) were reduced with 2 mg dithionite and extracted with 1 volume of ethyl acetate, and the organic phase was collected and dried over disodium sulfate. Derivatization by silylation was performed as described by Apajalahti and Salkinoja-Salonen (1). The samples were dissolved in ethyl acetate and analyzed using a Varian (Walnut Creek, CA) model 3800 gas chromatograph with a model 8200 autosampler equipped with a flame ionization detector. A 30-m DB1-ht column (100% methyl; inside diameter, 0.25 mm; film thickness, 0.1 μm; J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA) was used. The temperature program was as follows: 1 min at 50°C, followed by an increase in the temperature at a rate of 20°C/min to 150°C, a slower increase at a rate of 5°C/min to 200°C, and then an increase at a rate of 20°C/min to 320°C, which was held for 5 min. For unambiguous identification of compounds, samples were run on a Hewlett-Packard model 6890 gas chromatograph equipped with a model 5973 mass spectrometer (GC-MS) and the Chemstation analysis program (Hewlett-Packard, Kista, Sweden).

HPLC.

A. chlorophenolicus A6 cells, grown to the late log phase in GM medium with 1.2 mM 4-CP, were harvested by centrifugation, washed, and subsequently resuspended to an OD600 of 0.1 in 300 ml GM medium supplemented with 0.15 mM 4-CP, 4-chlorocatechol, or hydroquinone. The cultures were incubated with shaking at 28°C, and at regular intervals samples were taken and used for high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) and cell mass analyses. Prior to HPLC analysis 0.3 mg sodium dithionite was added to cell-free supernatants obtained after centrifugation. The concentrations of 4-CP and metabolites were determined with an Agilent 1100 high-pressure liquid chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany).

PCR, cloning, and sequencing.

Unless otherwise noted, the standard PCR conditions were as follows: each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 50 μM, each primer at a concentration of 0.7 μM, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 U Taq polymerase (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, England), and 10 ng A. chlorophenolicus A6 genomic DNA in a 50-μl reaction mixture. The reactions were performed with a Biometra Uno II thermocycler (Whatman Biometra, Göttingen, Germany).

Primers that annealed to conserved regions of hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase genes were designed by aligning the sequence of npdB, encoding this enzyme in Arthrobacter sp. strain JS443 (L. L. Perry and G. J. Zylstra, unpublished data), to the DNA sequence of ORF2 (20) and locating conserved regions. Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) was used for amplification from A. chlorophenolicus A6 genomic DNA.

A PCR walking system (15) was used to clone sequences from A. chlorophenolicus A6 (Table 1), and the PCR products were screened for similarity to cloned regions by Southern blotting. One set of primers was designed to anneal to conserved regions of maleylacetate reductase genes (Table 1). For PCR with these primers, the Expand system (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) was used.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Purpose | Position in accession no. AY131335 sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| CphAIf | ATGACGACCCGTCAAGTAGC | Expression of cphA-I | 8415-8434 |

| CphAIr | CTTCAGATCAGGATTAGGAGCAA | Expression of cphA-I | 9326-9304 |

| CphAIIf | ATGTCGGGAATCATCCATGCC | Expression of cphA-II | 12394-12374 |

| CphAIIr | TGCGAGGGCGGGGGCGAGGA | Expression of cphA-II | 11486-11505 |

| P1 | CTGAAACAACTCATGCAAGCCCT | Anneal to conserved region of hydroxyquionol dioxygenase gene | 8523-8545 |

| P2 | GGAGCGAGAACGATATCGAA | Anneal to conserved region of hydroxyquionol dioxygenase gene | 9310-9291 |

| P3 | TGGAACGGAC | Random primer | 5652-5661 |

| P4 | GCGATGGTCT | Anneal to clone c1 | 8707-8698 |

| P5 | AGTGCGCTGC | Random primer | 2181-2190 |

| P6 | CCGAAGTGGT | Anneal to clone c2 | 5981-5972 |

| P7 | GATCGTCAGC | Random primer | −9-0 |

| P8 | GGCATCGTTA | Anneal to clone c3 | 2405-2396 |

| P9 | GTCCAGGGTGACCCTTATAT | Anneal to clone c1 | 9147-9166 |

| P10a | TGCACCACAAGATNTGYCA | Anneal to conserved region of maleylacetate reductase | 12832-12814 |

| P11 | CGGTTCAGGA | Anneal to clone c6 | 13555-13564 |

| P12 | ATCACGAGGG | Random primer | 15017-15008 |

| P13 | TGCCCTACGA | Anneal to clone c7 | 14653-14662 |

| P14 | CAGCCGACGT | Random primer | 15476-15485 |

| CmxF | AGCATGTAGAGGGCAAAAGG | Anneal to internal fragment of Tn 1409Cβ | NAb |

| Tnp2 | AGAAGACGTGCTGGCGTACTTCGA | Anneal to internal fragment of Tn1409Cβ | NA |

| Tra1 | GCTGATAGGCGAACGCAACTGGTC | Screen cph cluster for transposon insertion | 315-338 |

| Tra2 | GTCGCGAACTGAACCGCTAACTCG | Screen cph cluster for transposon insertion | 7500-7477 |

| Tra3 | CACCGCGAGTTTGCTGCGAATTAT | Screen cph cluster for transposon insertion | 7042-7065 |

| Tra4 | TCTGGCACCTTACGGCCAATTCAC | Screen cph cluster for transposon insertion | 13842-13819 |

Degenerate primer.

NA, not applicable.

Part of the cph cluster (clone c6) was obtained by creating a subgenomic library. Southern blotting of EcoRI-digested A. chlorophenolicus A6 genomic DNA revealed that a 2,000-bp fragment hybridized to the cphF-II open reading frame (ORF) (this study). Therefore, EcoRI fragments in the size range from 1,800 to 2,200 bp were cloned into pUC18. Positive clones that hybridized to cphF-II were identified by colony hybridization, and the inserts were sequenced.

To overexpress cphA-I and cphA-II, the ORFs were PCR amplified from A. chlorophenolicus A6 genomic DNA (Table 1) and cloned into the vector pCRT7/CT-TOPO (Invitrogen), which created C-terminal six-His-tagged fusions to the genes. The constructs were transformed into competent BL21(DE3)/pLysS cells (Invitrogen), and cultivation and induction were performed as specified by the manufacturers.

Preparation of cell extracts.

A. chlorophenolicus A6 cells were harvested by centrifugation, suspended in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and passed once through a French press (164 MPa). The lysate was centrifuged at 9,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was recovered.

Crude extracts of E. coli expressing CphA-I or CphA-II were prepared in 2 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and were disrupted by three sonication treatments (1 min each) at 0°C with a Branson Sonifier 250 at an output level of 5.5 (18 W). Each lysate was centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 30 min, and the supernatant was saved and used as a crude cell extract.

Enzyme activity assays.

Hydroxyquinol removal, 4-chlorocatechol removal, and catechol removal were monitored separately in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) with 5 to 141 μg crude cell extract and 0.2 mM substrate in a 1-ml (final volume) (E. coli) or 0.5-ml (final volume) (A. chlorophenolicus A6) mixture using a Shimadzu UV-2501 PC or Hitachi U-2000 dual-beam spectrophotometer, as previously described (24). In the hydroxyquinol assay a maleylacetate peak at 245 nm was also detected. One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to catalyze the oxidation of 1 μmol hydroxyquinol in 1 min. Catechol 1,2-dioxygenase activity was detected by measuring the increase in absorbance at 260 nm for cis,cis-muconate, and 1 U of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that produced 1 μmol cis,cis-muconate in 1 min.

Mutant construction.

A. chlorophenolicus A6 was transformed with plasmid pKGT452Cβ, which contains an Arthrobacter-derived, randomly inserting transposon conferring chloramphenicol resistance (10). Preparation of A. chlorophenolicus A6 cells and electroporation were performed as described previously (18). After recovery in 10% LB for 2 h, the cells were inoculated onto agar plates containing 10% LB and 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol and incubated at 28°C for 3 days. Chloramphenicol-resistant clones (approximately 2,000 clones) were transferred to plates containing GM medium with 1.2 mM 4-CP as the sole carbon source and 5 μg/ml chloramphenicol. The wild-type strain A. chlorophenolicus A6 did not exhibit any visible growth on medium containing chloramphenicol. Clones that grew poorly on 4-CP were subjected to further screening. Transposon insertions in the cph gene cluster were screened using PCR primers Tra1, Tra2, Tra3, and Tra4 (Table 1) targeted to internal regions of the gene cluster. Single chromosomal insertion of a transposon was detected as a size increase of 3,409 bp in the amplified fragment combined with Southern blotting using a 414-bp fragment of the transposon's chloramphenicol resistance gene as a probe.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence described here has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession number AY131335.

RESULTS

Stoichiometric release of chloride ions from 4-CP.

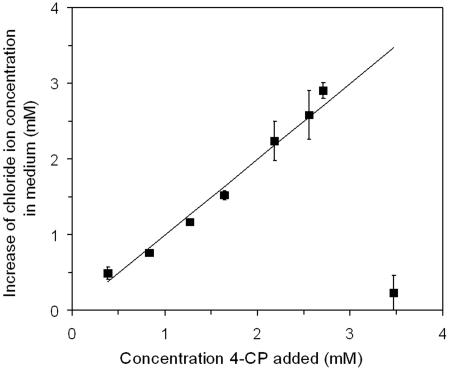

Chloride ions were released in stoichiometric amounts from 4-CP at increasing substrate concentrations up to 2.7 mM, which is the highest 4-CP concentration on which A. chlorophenolicus A6 can grow (28) (Fig. 1). These data corroborate previous results from studies with 14C-labeled 4-CP (29) indicating that A. chlorophenolicus mineralizes 4-CP to carbon dioxide, chloride ions, and water.

FIG. 1.

Release of chloride ions by A. chlorophenolicus A6 during growth on different concentrations of 4-CP. The theoretical stoichiometric release is indicated by a straight line. The symbols indicate the means for three replicates, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations of the means (n = 3).

Detection of potential 4-CP metabolites.

Four potential metabolites (designated compounds I, II, III, and IV) were detected in cultures of A. chlorophenolicus A6 growing on 4-CP. Compounds I, II, and III were identified as hydroquinone, 4-chlorocatechol, and hydroxyquinol, respectively, by gas chromatography with flame ionization detection and by GC-MS analysis (Table 2). Compound IV did not cochromatograph with any standard. GC-MS analysis revealed that the fragmentation pattern of compound IV was consistent with that of a chlorohydroxyquinol, and the spectrum was similar to the chlorohydroxyquinol spectrum described by Apajalahti and Salkinoja-Salonen (1) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Fragmentation patterns of 4-CP metabolites as determined by GC-MS analysis

| Compound | Retention time (min) | m/z of observed fragment ions | Identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 6.15 | 254 (M+), 239 (M - CH3), 73 [Si(CH3)3] | Silylated hydroquinone |

| II | 6.71 | 290, 288 (M+), 275, 273 (M - CH3), 200, 185, 170, 73 [Si(CH3)3] | Silylated 4-chlorocatechol |

| III | 7.76 | 342 (M+), 327 (M - CH3), 254, 239, 73 [Si(CH3)3] | Silylated hydroxyquinol |

| IV | 9.11 | 378, 376 (M+), 363, 361 (M - CH3), 288, 275, 273, 237, 179, 73 [Si(CH3)3] | Silylated chlorohydroxyquinol |

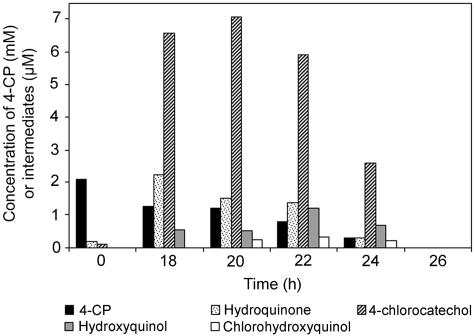

4-CP degradation by A. chlorophenolicus A6 and production of intermediates were studied during growth on 4-CP as a sole carbon source at a concentration of 2.1 mM. After 20 h of incubation, when the cultures were in the mid-log phase, 4-chlorocatechol was the metabolite that accumulated to the highest levels (Fig. 2). At earlier incubation times (5 to 6 h, cells in the lag phase) hydroquinone and 4-chlorocatechol were the only detectable metabolites, and their concentrations were approximately 7 μM and 12 μM, respectively (data not shown). After 26 h of incubation, no intermediates were detected in the medium. When succinate or yeast extract was present as an auxiliary substrate, 4-CP degradation was delayed until the substrate was depleted (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Results of a representative experiment showing metabolite accumulation during growth of A. chlorophenolicus A6 on 2.1 mM 4-CP.

In a separate set of experiments, potential metabolites of 4-CP degradation were exogenously added to 4-CP-induced cells, and their rates of removal in triplicate cultures were monitored. The cell densities were adjusted to an OD600 of 0.1 as this value was the cell density in the mid-log phase during growth on 4-CP as a sole carbon source. We found that there was not a significant difference (P < 0.01) between the degradation rates of hydroquinone and 4-CP and that both compounds were degraded at a rate of 179 μmol/g cells/min. By contrast, 4-chlorocatechol removal was significantly slower (78 μmol/g cells/min), and there was a sharp decline in the rate after 1.5 h of incubation. The only metabolite that was detected upon incubation with 4-chlorocatechol in repeated experiments was chlorohydroxyquinol (average concentration, 3.0 μM; n = 3). No 4-chlorocatechol or catechol dioxygenase activity was detected in 4-CP-induced cell extracts that exhibited confirmed activity with hydroxyquinol, indicating that classical 4-chlorocatechol metabolism via the ortho cleavage pathway was not induced.

We also studied the impact of an inhibitor of ring cleavage dioxygenases, 2,2′-dipyridyl (6), on the growth of A. chlorophenolicus cells. Actively 4-CP-degrading cultures changed color within minutes after 2,2′-dipyridyl addition and eventually became deep red, which was indicative of hydroxyquinol accumulation (14). In four separate experiments, hydroxyquinol accumulated to levels that were approximately 12% of the 4-CP concentration at the time of 2,2′-dipyridyl addition.

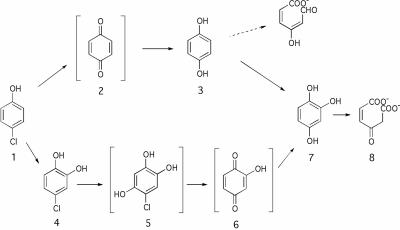

Another indication of hydroxyquinol dioxygenase activity was the ability of cell extracts from 4-CP-grown cells to deplete hydroxyquinol from the medium with an activity of 96 mU/mg protein (standard deviation, 4.4 mU/mg protein; n = 3). This activity was apparently induced in the presence of 4-CP since no depletion of hydroxyquinol was measured in extracts of succinate-grown cells (detection limit, 3.7 mU/mg protein). Based on these results, we propose a 4-CP degradation pathway via ring cleavage of hydroxyquinol (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Proposed 4-CP degradation pathway in A. chlorophenolicus A6. Compound 1, 4-CP; compound 2, benzoquinone; compound 3, hydroquinone; compound 4, 4-chlorocatechol; compound 5, 5-chlorohydroxyquinol; compound 6, 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone; compound 7, hydroxyquinol; compound 8, maleylacetate. The transformation from compound 5 to compound 6 is theoretically due to reductive dechlorination of compound 5. Compound 6 is presented in a different orientation with respect to compound 5 for ease of presentation of the rest of the pathway. The presence of maleylacetate is inferred from genetic and biochemical evidence. Brackets indicate hypothetical intermediates supported, but not confirmed, by our data. An alternative hydroquinone cleavage route to hydroxymuconic semialdehyde that is not supported by our data is indicated by a dashed arrow.

Cloning of a cph gene cluster.

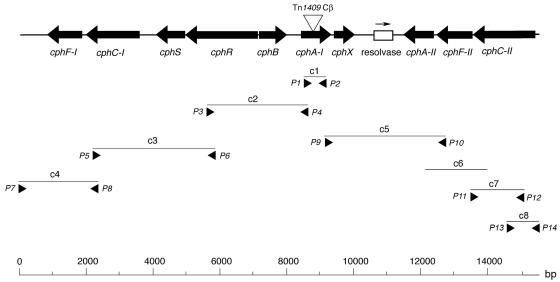

Southern blot analysis indicated that A. chlorophenolicus A6 contains a gene similar to the npdB gene, which encodes a hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase in Arthrobacter sp. strain JS443 (Perry and Zylstra, unpublished). A similar, but not identical, sequence was cloned from A. chlorophenolicus A6 using PCR primers designed to anneal to conserved regions in hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase genes (fragment c1 in Fig. 4; Table 1). Flanking sequences (c2 to c5, c7, and c8 in Fig. 4) were cloned and sequenced using a combination of primer walking and PCR amplification with primers targeted to conserved sequences of predicted genes (Table 1 and Fig. 4). One region (c6) (Fig. 4) was identified by screening a subgenomic library. The combined sequences generated a 15,475-bp contiguous stretch of A. chlorophenolicus A6 DNA (Fig. 4). The best matches with existing sequences in databases for the ORFs are shown in Table 3. Based on the results of these analyses, the gene organization shown in Fig. 4 is proposed, and the putative genes were designated cph (chlorophenol degradation).

FIG. 4.

Proposed cph gene cluster, including plasmid clones and primers (Table 1). The position of each clone is indicated below the line representing the consensus sequence, and primers are indicated by arrowheads. The triangle indicates the site of insertion of Tn1409Cβ in mutant T99.

TABLE 3.

Amino acid sequence comparisons

| Gene product | Position in accession no. AY131335 sequence | Similar protein | Function (gene, organism) | % Identitya | Score (bits) | E value | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CphF-I | 795-1859 (complement) | PnpD | Maleylacetate reductase, Ralstonia sp. strain SJ98 | 45.8 | 302 | 1e-80 | AAS87585 |

| CphC-I | 1965-3572 (complement) | NpcA | Oxygenase component of 4-nitrophenol monooxygenase, Rhodococcus opacus | 72.0 | 825 | 0.0 | BAD30042 |

| CphS | 4060-4950 (complement) | TfuA | Involved in trifolitoxin production, Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii T24 | 12.4 | 58 | 2e-07 | AAB17513 |

| CphR | 4954-7098 (complement) | AcoK | trans-Acting regulatory protein of aco operon, Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43 | 17.2 | 95 | 6e-18 | AAC44880 |

| CphB | 7169-7996 | NpcB | Reductase component of 4-nitrophenol monooxygenase, Rhodococcus opacus | 37.1 | 141 | 2e-32 | BAD30041 |

| CphA-I | 8415-9329 | ORF2 | Hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase, Arthrobacter strain BA-5-17 | 75.7 | 467 | e-130 | BAA82713 |

| CphX | 9419-10048 | ProX | Unknown function in phthalate degradation, Pseudomonas straminea NGJ1 | 28.9 | 74 | 2e-12 | BAB21454 |

| CphA-II | 11483-12394 (complement) | ORF2 | Hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase, Arthrobacter strain BA-5-17 | 77.6 | 491 | e-138 | BAA82713 |

| CphF-II | 12465-13541 (complement) | PnpD | Maleylacetate reductase, Ralstonia sp. strain SJ98 | 44.4 | 286 | 4e-76 | AAS87585 |

| CphC-II | 13545-15341 (complement) | PheA | Phenol 2-monooxygenase, Pseudomonas sp. strain EST1001 | 62.9 | 762 | 0.0 | AAC64901 |

For calculation of percent identity, gaps were treated as a 21st amino acid, but terminal gaps were ignored.

Several of the ORFs in the cph cluster were predicted to encode proteins with similar functions. For example, there were two hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenases (encoded by cphA-I and cphA-II), two putative monooxygenases (cphC-I and cphC-II), and two putative maleylacetate reductases (cphF-I and cphF-II). The cphB gene could encode an NADH:flavin adenine dinucleotide oxidoreductase to supply the monooxygenase encoded by cphC-I with reduced flavin adenine dinucleotide (Table 3).

When the derived amino acid sequences of CphA-I and CphA-II were aligned with the sequences of other intradiol-cleaving enzymes, we found that two histidyl and tyrosyl residues coordinating the ferric iron in protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas putida were also conserved in CphA-I and CphA-II (23). The amino acid sequence of CphA-II was 78.4% identical to that of CphA-I.

The cphX ORF showed some similarity to a gene with an unknown function found in a phthalate degradation gene cluster in Pseudomonas straminea (17). There were also some similarities to molybdate transport proteins. However, due to the low quality of the database hits we were not able to assign a putative function to this ORF.

There were several indications that some of the ORFs with duplicated functions in the cph cluster were derived via a horizontal gene transfer event. To begin with, the region from position 10599 to position 11158 between cphX and cphA-II (Fig. 4) is a nonfunctional, putative resolvase pseudogene that was calculated to be, on the DNA level, 65% identical to the resolvase gene in the Tn21 family of the phthalate degradation pathway genes in Arthrobacter keyseri (accession number AF331043) and also 65% identical to Tn1721 in E. coli (accession number X02590). In addition, analyses of G+C contents revealed that the ORFs upstream of the resolvase gene in Fig. 4 had lower total G+C contents (56 to 59.6%) than the A. chlorophenolicus genome as a whole (65.1%), whereas the ORFs downstream of the resolvase gene had similar G+C contents (62.1 to 67.1%). Moreover, the third-position G+C content and the effective number of codons (30) of the ORFs upstream of the resolvase gene differed from the values for the downstream ORFs, which had values more similar to those obtained for Arthrobacter globiformis, the type species of the genus (13; data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that the region of the cph gene cluster upstream of the resolvase gene was acquired via horizontal gene transfer from another organism (22).

Expression of cphA-I and cphA-II in E. coli.

Recombinant cphA-I and cphA-II were overexpressed in E. coli, and hydroxyquinol removal was studied in crude extracts with measured activities of 16 and 3.0 U/mg protein, respectively. In addition, CphA-I and CphA-II exhibited some ortho cleavage activity with catechol (0.67 mU/mg protein for CphA-I and 0.15 mU/mg protein for CphA-II), which has also been detected for other bacterial hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenases (2, 20). Neither CphA-I (1.6 U) nor CphA-II (0.3 U) exhibited activity with 4-chlorocatechol, hydroquinone, or resorcinol (with 6 min of incubation and a reaction setup like that used for hydroxyquinol). Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis revealed that the molecular masses of recombinant CphA-I and CphA-II were 40 kDa and 42 kDa, respectively (data not shown). Both of these observed molecular masses are slightly larger than the values expected (theoretically 33.5 and 33.0 kDa, respectively, plus the 3.3-kDa His tag), which could have been due to posttranslational modification of the proteins and/or running anomalies in the gel.

Generation and analysis of a cphA-I knockout mutant.

We used transposon mutagenesis to disrupt the cphA-I gene, which generated mutant strain A. chlorophenolicus T99 (Fig. 4). Sequencing of the transposon insertion site revealed a duplication of 8 bases (positions 8862 to 8869 in the cph gene cluster) at the point of insertion, which is consistent with properties of the Tn1409Cβ transposon (10). The mutant contained a single transposon insertion, as verified by Southern blotting (data not shown). In repeated experiments we confirmed that unlike the wild-type strain, the T99 mutant was not able to grow on 1.2 mM 4-CP as a sole carbon source, as shown by no visible increase in cell density after 40 h of incubation. In addition, a red-orange color accumulated during incubation of the mutant with 4-CP, which indicated that there was hydroxyquinol accumulation. Therefore, 4-CP catabolic ability was disrupted by the transposon insertion in the cphA-I gene.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that A. chlorophenolicus A6 degrades 4-CP via hydroxyquinol. To begin with, this compound was found in culture medium during 4-CP degradation. In addition, hydroxyquinol was removed from cell extracts derived from 4-CP-grown cells but not from extracts of cells grown on succinate. Therefore, there is clearly induction of the ability to remove hydroxyquinol when 4-CP is the growth substrate compared to when an alternative substrate is used. Furthermore, our results suggest that hydroxyquinol is the ring cleavage substrate during 4-CP degradation by A. chlorophenolicus A6 (Fig. 3). This hypothesis is supported by our observation that hydroxyquinol accumulates upon iron chelation (i.e., conditions under which the ring cleavage enzyme is inhibited). However, we did not observe a 1:1 accumulation of hydroxyquinol from 4-chlorophenol, which could have been due to the chemical instability of this compound (32) or incomplete inhibition.

In support of the biochemical evidence, a gene cluster containing genes encoding two hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenases, CphA-I and CphA-II, was cloned from the A. chlorophenolicus A6 genome. Also, we successfully inactivated the cphA-I gene by transposon mutagenesis, and mutant strain T99 could not utilize 4-CP as a carbon source. Therefore, CphA-I (a hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase according to BLAST homology search results and the activity when it was expressed in E. coli) is required for 4-CP transformation and mineralization in this organism. However, we cannot completely disregard the possibility that the lack of growth was due to polar effects on cphX, whose function is currently unknown. Although the cphA-II gene was intact in the mutant strain and produced a functional protein when it was expressed in E. coli, it was insufficient to enable growth of the T99 mutant strain on 4-CP, and thus its functional significance in vivo is currently not known. Possibly, the gene is not optimally transcribed, or it is subject to negative gene regulation under these conditions. Taken together, the combined chemical and genetic evidence indicates that 4-CP degradation in A. chlorophenolicus A6 proceeds via hydroxyquinol, which is subsequently cleaved. To our knowledge, this is the first time that such a pathway has been described for aerobic 4-CP degradation by a bacterium.

4-Chlorocatechol, chlorohydroxyquinol, and hydroquinone were also found to be metabolites in addition to hydroxyquinol during growth on 4-CP. The logical positions of these compounds in the proposed degradation route are shown in Fig. 3; chlorohydroxyquinol is in brackets as it has not been confirmed to be an intermediate. In accordance with previous reports, the oxidation and simultaneous removal of a chlorine group from the aromatic ring by a monooxygenase are likely to yield a quinone that can then be reduced to the corresponding quinol (31), and although this possibility was not addressed in the present work, the resulting quinone is shown in brackets in Fig. 3. Although A. chlorophenolicus A6 removed 4-chlorocatechol at a rate that was approximately one-half the rate of hydroquinone removal, the 4-chlorocatechol branch shown in Fig. 3 could theoretically still significantly contribute to 4-CP degradation in this strain.

The proposed transformation of 4-CP via hydroquinone to hydroxyquinol in A. chlorophenolicus A6 is similar to the transformation commonly found in the degradation of tri- to pentachlorophenols; however, the hydroquinone is chlorinated in these cases (24). In addition, transformation of nonchlorinated hydroquinone to hydroxyquinol has been suggested for degradation of 4-aminophenol (26). Another possibility is that hydroquinone, and not hydroxyquinol, is the ring cleavage substrate in A. chlorophenolicus A6, and this possibility is indicated by the dashed line in Fig. 3. Hydroxyquinol could then be transformed into hydroquinone prior to ring cleavage, as has been reported to occur in 4-nitrophenol degradation (7). However, the observed accumulation of hydroxyquinol in 2,2′-dipyridyl-inhibited cultures and the results of the cphA-I mutant studies discussed above support the possibility that there is ring cleavage directly from hydroxyquinol.

We also detected chlorohydroxyquinol in culture medium during 4-CP degradation. This compound could be formed by hydroxylation of 4-chlorocatechol and then dechlorinated to hydroxyquinol; the latter reaction is analogous to transformation of 5-chlorohydroxyquinol to hydroxyquinol by Burkholderia cepacia AC1100 during 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid degradation (32). Chlorohydroxyquinol would then be an intermediate between 4-chlorocatechol and hydroxyquinol in 4-CP degradation by A. chlorophenolicus A6 (Fig. 3), but this possibility remains to be resolved.

A. chlorophenolicus A6 can also degrade 4-nitrophenol, and although it was outside the scope of this study to elucidate the degradation pathway for this compound, 4-nitrophenol has been reported to be degraded via cleavage of both hydroquinone (25) and hydroxyquinol (14). Kitagawa et al. (14) recently cloned a 4-nitrophenol catabolic gene cluster containing a hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase with sequence similarity to CphA-I and CphA-II and a two-component monooxygenase similar to the CphC-I and CphB in this study. Possibly, the same enzyme system could be used for 4-CP degradation and 4-nitrophenol degradation in A. chlorophenolicus A6.

Two different types of monooxygenases are predicted to be present in A. chlorophenolicus A6. The CphC-I and CphB sequences were most similar to a two-component monooxygenase involved in 4-nitrophenol degradation (Table 3) (14). This type of monooxygenase, in which the large subunit is the oxygenase which receives electrons from the small subunit, an NADH:flavin adenine dinucleotide oxidoreductase, has also been found to be involved in degradation of 2,4,6-trichlorophenol (16, 27). The second putative monooxygenase in the cph gene cluster, CphC-II, was similar to a different family of monooxygenases, the flavin monooxygenases, which are not dependent on an oxidoreductase but instead transfer electrons from NAD(P)H to a flavin which is situated at the active site (11). Another difference from CphC-I is that the deduced CphC-II protein was most similar to a phenol monooxygenase acting on nonchlorinated substrates (21). In future studies, expression of the putative monooxygenases and studies of their functions may shed light on the transformations prior to ring cleavage.

Three of the steps in the degradation pathway (addition of hydroxyl groups to 4-CP, cleavage of the aromatic ring, and reduction of maleylacetate) are represented by double sets of genes in A. chlorophenolicus A6 (Fig. 4). The presence of some of the genes appears to be due to lateral gene transfer since in the cph gene cluster there is a marked difference in G+C content between ORFs and the cluster contains a putative resolvase pseudogene, both of which are typical indications of a past horizontal gene transfer event (22). The ORFs apparently encoding isofunctional enzymes in A. chlorophenolicus A6 showed marked sequence differences. The two predicted monooxygenases appeared to be different types, as discussed above. Also, detailed phylogenetic analysis revealed that CphA-I was more closely related to NpdB, an isofunctional enzyme from Arthrobacter sp. strain JS443 (Perry and Zylstra, unpublished), than to CphA-II (not shown). Similar to the results of the present work, several cases of multiple copies of genes for catechol degradation have previously been reported (19).

In summary, in this study we identified both a chlorophenol degradation pathway and a 4-CP degradation gene cluster in A. chlorophenolicus A6. In future studies we plan to clarify the roles of the remaining genes in the cph gene cluster, such as cphX, and to determine how these genes are regulated in this bacterium.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karl-Heinz Gartemann and Rudolf Eichenlaub at Universität Bielefeld, Germany, for the kind gift of the pKGT452Cβ vector; Ingvar Sundh and Elisabet Börjesson at the Swedish Agricultural University for help with the GC-MS analysis; Åsa Perez-Bercoff for technical assistance with the codon bias analysis; and Gerben J. Zylstra at Rutgers University for the kind gift of the npdB gene.

This work was suported by grants from the Swedish Council for Engineering Science and the Swedish Foundation for Environmental Research (MISTRA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Apajalahti, J. H. A., and M. S. Salkinoja-Salonen. 1987. Complete dechlorination of tetrachlorohydroquinone by cell extracts of pentachlorophenol-induced Rhodococcus chlorophenolicus. J. Bacteriol. 169:5125-5130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armengaud, J., K. N. Timmis, and R.-M. Wittich. 1999. A functional 4-hydroxysalicylate/hydroxyquinol degradative pathway gene cluster is linked to the initial dibenzo-p-dioxin pathway genes in Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. J. Bacteriol. 181:3452-3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Backman, A., and J. K. Jansson. 2004. Degradation of 4-chlorophenol at low temperature and during extreme temperature fluctuations by Arthrobacter chlorophenolicus A6. Microb. Ecol. 48:246-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Backman, A., N. Maraha, and J. K. Jansson. 2004. Impact of temperature on the physiological status of a potential bioremediation inoculant, Arthrobacter chlorophenolicus A6. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2952-2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bae, H. S., J. M. Lee, and S.-T. Lee. 1996. Biodegradation of 4-chlorophenol via a hydroquinone pathway by Arthrobacter ureafaciens CPR706. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 145:125-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman. P. J., and D. J. Hopper. 1968. The bacterial metabolism of 2,4-xylenol. Biochem. J. 110:491-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chauhan, A., A. K. Chakraborti, and R. K. Jain. 2000. Plasmid-encoded degradation of p-nitrophenol and 4-nitrocatechol by Arthrobacter protophormiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 270:733-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho, Y.-G., J.-H. Yoon, Y.-H. Park, and S.-T. Lee. 1998. Simultaneous degradation of p-nitrophenol and phenol by a newly isolated Nocardioides sp. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 44:303-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elväng, A. M., K. Westerberg, C. Jernberg, and J. K. Jansson. 2001. Use of green fluorescent protein and luciferase biomarkers to monitor survival and activity of Arthrobacter chlorophenolicus A6 cells during degradation of 4-chlorophenol in soil. Environ. Microbiol. 3:32-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gartemann, K.-H., and R. Eichenlaub. 2001. Isolation and characterization of IS1409, an insertion element of 4-chlorobenzoate-degrading Arthrobacter sp. strain TM1, and development of a system for transposon mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol. 183:3729-3736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harayama, S., and M. Kok. 1992. Functional and evolutionary relationships among diverse oxygenases. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 46:565-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jernberg, C., and J. K. Jansson. 2002. Impact of 4-chlorophenol contamination and/or inoculation with the 4-chlorophenol-degrading strain, Arthrobacter chlorophenolicus A6L, on soil bacterial community structure. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 42:387-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keddie, R. M., M. D. Collins, and D. Jones. 1986. Genus Arthrobacter Conn and Dimmick 1947, 300AL, p. 1228-1301. In P. H. A. Sneath, N. S. Mair, M. E. Sharpe, and J. G. Holt (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, vol. 2. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Md. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitagawa, W., N. Kimura, and Y. Kamagata. 2004. A novel p-nitrophenol degradation gene cluster from a gram-positive bacterium, Rhodococcus opacus SAO101. J. Bacteriol. 186:4894-4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin, X., D. W. Kelemen, E. S. Miller, and J. C. H. Shih. 1995. Nucleotide sequence and expression of kerA, the gene encoding a keratinolytic protease of Bacillus licheniformis PWD-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1469-1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Louie, T. M., C. M. Webster, and L. Xun. 2002. Genetic and biochemical characterization of a 2,4,6-trichlorophenol degradation pathway in Ralstonia eutropha JMP134. J. Bacteriol. 184:3492-3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maruyama, K., M. Miwa, N. Tsujii, T. Nagai, N. Tomita, T. Harada, H. Sobajima, and H. Sugisaki. 2001. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the gene encoding 4-hydroxy-4-methyl-2-oxoglutarate aldolase from Pseudomonas ochraceae NGJ1. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 65:2701-2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Möller, A., and J. K. Jansson. 1998. Detection of firefly luciferase-tagged bacteria in environmental samples. Methods Mol. Biol. 102:269-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murakami, S., A. Takashima, J. Takemoto, S. Takenaka, R. Shinke, and K. Aoki. 1999. Cloning and sequence analysis of two catechol-degrading gene clusters from the aniline-assimilating bacterium Frateuria species ANA-18. Gene 226:189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murakami, S., T. Okuno, E. Matsumura, S. Takenaka, R. Shinke, and K. Aoki. 1999. Cloning of a gene encoding hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase that catalyzes both intradiol and extradiol ring cleavage of catechol. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 63:859-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nurk, A., L. Kasak, and M. Kivisaar. 1991. Sequence of the gene (pheA) encoding phenol monooxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. EST1001: expression in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas putida. Gene 102:13-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ochman, H., J. G. Lawrence, and E. A. Groisman. 2000. Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation. Nature 405:299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohlendorf, D. H., J. D. Lipscomb, and P. C. Weber. 1988. Structure and assembly of protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase. Nature 336:403-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Padilla, L., V. Matus, P. Zenteno, and B. González. 2000. Degradation of 2,4,6-trichlorophenol via chlorohydroxyquinol in Ralstonia eutropha JMP134 and JMP222. J. Basic Microbiol. 4:243-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prakash, D., A. Chauhan, and R. K. Jain. 1996. Plasmid-encoded degradation of p-nitrophenol by Pseudomonas cepacia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 224:375-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takenaka, S., S. Okugawa, M. Kadowaki, S. Murakami, and K. Aoki. 2003. The metabolic pathway of 4-aminophenol in Burkholderia sp. strain AK-5 differs from that of aniline and aniline with C-4 substituents. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5410-5413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takizawa, N., H. Yokoyama, K. Yanagihara, T. Hatta, and H. Kiyohara. 1995. A locus of Pseudomonas pickettii DTP0602, had, that encodes 2,4,6-trichlorophenol-4-dechlorinase with hydroxylase activity, and hydroxylation of various chlorophenols by the enzyme. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 80:318-326. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westerberg, K., A. M. Elväng, E. Stackebrandt, and J. K. Jansson. 2000. Arthrobacter chlorophenolicus sp. nov., a new species capable of degrading high concentrations of 4-chlorophenol. Int. J. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 50:2083-2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westerberg, K., C. Jernberg, A. M. Elväng, and J. K. Jansson. 2001. Arthrobacter chlorophenolicus A6—the complete story of a 4-chlorophenol degrading bacterium, p. 133-140. In V. S. Magar, G. Johnson, S. K. Ong, and A. Leeson (ed.), Bioremediation of energetics, phenolics, and polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons. Proceedings of the Sixth International In Situ and On-Site Bioremediation Symposium. Battelle Press, Columbus, Ohio.

- 30.Wright, F. 1990. The ‘effective number of codons’ used in a gene. Gene 87:23-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xun, L., and C. M. Webster. 2004. A monooxygenase catalyzes sequential dechlorinations of 2,4,6-trichlorophenol by oxidative and hydrolytic reactions. J. Biol. Chem. 279:6696-6700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaborina, O., D. L. Daubaras, A. Zago, L. Xun, K. Saido, T. Klem, D. Nikolic, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1998. Novel pathway for conversion of chlorohydroxyquinol to maleylacetate in Burkholderia cepacia AC1100. J. Bacteriol. 180:4667-4675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]