Abstract

We investigated the activities of linezolid, vancomycin, and teicoplanin in a murine model of hematogenous pulmonary infection with Staphylococcus aureus. Our results demonstrate that linezolid clearly reduced bacterial numbers in the methicillin-resistant S. aureus hematogenous infection model and significantly improved the survival rate of immunocompromised mice infected with vancomycin-insensitive S. aureus compared with vancomycin and teicoplanin. The pharmacokinetic profiles also reflected the effectiveness of linezolid.

In 1997, the first strain of Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin and teicoplanin was reported from Japan (4). Soon thereafter, a report of two additional cases from the United States was published (8). Although infection with S. aureus that exhibits decreased susceptibility to vancomycin is currently rare, there is a pressing need to establish effective therapy for vancomycin-insensitive S. aureus (VISA) infection.

Linezolid is one of the oxazolidinones, a new class of antimicrobials with a unique mechanism of action, and its effectiveness against methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) or VISA has been highly anticipated [1; M. C. Birmingham, R. R. Craig, B. Hafkin, W. M. Todd, S. M. Flavin, J. D. Root, G. S. Zimmer, D. H. Batts, and J. J. Schentag, Soc. Crit. Care Med. 29th Educ. Sci. Symp. 2000, abstr. 42, Crit. Care Med. 27(Suppl. S):A33, 1999].

We established a new murine model of pulmonary infection with S. aureus by intravenous injection of bacteria enmeshed in agar beads (7). Using this model, we evaluated the effects of linezolid against MRSA and VISA and compared them with those of vancomycin and teicoplanin.

Male 6-week-old specific-pathogen-free ddY mice (body weight, 20 to 25 g) were purchased from Shizuoka Agricultural Cooperative Association Laboratory Animals (Shizuoka, Japan). All animals were housed in a pathogen-free environment and provided with sterilized food and water in the Animal Center for Biomedical Science at Nagasaki University. The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Care Ethics Review Committee of our institution.

MRSA NUMR 101, which was isolated from clinical samples at Nagasaki University Hospital, and VISA Mu50 (a clinical isolate, provided by Keiichi Hiramatsu, Juntendo University) were used for this study.

Linezolid, vancomycin, and teicoplanin were obtained from Pharmacia (Tokyo, Japan), Shionogi Pharmaceutical Co. (Osaka, Japan), and Aventis (Tokyo, Japan), respectively. MICs of antibiotics were determined by the broth dilution method with Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.).

The method of inoculation was described previously (7). The organisms were suspended in cold sterile saline and diluted to 2 × 109 to 4 × 109 CFU/ml, as estimated by turbidimetry. The suspension was warmed to 45°C, and then 10 ml of the suspension was mixed with 10 ml of 4% (wt/vol) molten Noble agar (Difco Laboratories) at 45°C. The agar-bacterium suspension (1.0 ml) was rapidly injected via a 26-gauge needle into 49 ml of rapidly stirred ice-cooled sterile saline. The final concentration of agar was 0.04% (wt/vol), and the final number of bacteria was 2 × 107 to 4 × 107 CFU/ml.

Mice infected with VISA were pretreated with cyclophosphamide at 1 and 3 days before inoculation, and their survival rate was recorded daily over a period of 10 days.

We injected 0.20 to 0.25 ml into the tail vein of each of five mice. Forty animals for the MRSA study and 80 animals for the VISA study were allocated into four treatment groups: linezolid (100 mg/kg of body weight/day), vancomycin (100 mg/kg/day), teicoplanin (100 mg/kg/day), and saline for the control group. Each antibiotic was injected intraperitoneally twice a day from 24 h after inoculation for 7 days (MRSA study) or 10 days (VISA study).

Each group of animals was sacrificed at specific time intervals by cervical dislocation. After exsanguination, the lungs were dissected and removed under aseptic conditions. Organs used for bacteriological analyses were homogenized and cultured quantitatively by serial dilutions on blood agar plates. Lung tissue for histological examination was fixed in 10% buffered formalin and stained with hematoxylin-eosin.

Animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h after treatment. Serum and lung samples were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography for linezolid concentration (5). Concentrations of vancomycin and teicoplanin were determined by fluorescence polarization immunoassay (6, 10). Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated from arithmetic means of concentrations in serum and lung tissue.

Differences between groups were examined for statistical significance by the unpaired U test. A P value of <0.05 denoted the presence of a statistically significant difference. The survival rate was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method.

For the MRSA and VISA strains used, the MICs of linezolid, vancomycin, and teicoplanin were 2 and 1, 1 and 8, and 0.5 and 8 μg/ml, respectively.

In the untreated and linezolid-treated groups, 7.75 ± 0.37 and 6.39 ± 0.48 log CFU/ml (mean ± standard deviation) MRSA organisms were detected, respectively, which represented a significant decrease of viable bacterial numbers in the linezolid group (n = 10, P < 0.001). Compared with vancomycin (7.25 ± 0.88 log10 CFU/ml), linezolid significantly (P < 0.05) reduced the number of bacteria detected in the MRSA hematogenous infection model. The results for the teicoplanin-treated group were 6.91 ± 0.69 log10 CFU/ml.

Survival rates were 85% in the linezolid-treated group and 40 to 45% in the other three groups (vancomycin, teicoplanin, and untreated). Linezolid, therefore, significantly improved the survival rate (85 versus 40 or 45%; P < 0.05) and decreased mortality (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Effects of linezolid, vancomycin, and teicoplanin (all at 100 mg/kg/day) on survival rate of animals with VISA hematogenous pulmonary infection. Mice were treated with each antibiotic after infection with VISA. The survival percentages of mice were determined for 10 days. At 10 days, 85% of mice in the linezolid-treated group and 40 to 45% of mice in the other three groups (vancomycin, teicoplanin, and untreated) survived. Linezolid significantly improved survival rate (85 versus 40 or 45%; P < 0.05 [asterisk]). Symbols: •, linezolid; □, vancomycin; ▪, teicoplanin; and ○, control.

Figure 2 shows the mean concentrations in serum (Fig. 2a) and lung tissue (Fig. 2b) of linezolid, vancomycin, and teicoplanin at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h after administration. Table 1 shows the pharmacokinetic parameters in lung tissue in MRSA infection. Of the antibiotics analyzed, the time for which the area under the time-concentration curve (AUC) was higher than the MIC (AUC > MIC) was highest for linezolid.

FIG. 2.

Pharmacokinetics of linezolid, vancomycin, and teicoplanin (all at 100 mg/kg/day) in the sera (a) and the lungs (b) of infected mice. Drugs were administered intraperitoneally twice daily from 24 h after infection. Results are presented as means ± standard errors of the means (sera) or means ± standard deviations (lung). Symbols: •, linezolid; ▪, vancomycin; and □, teicoplanin.

TABLE 1.

Selected pharmacokinetic parameter estimates for antibiotics in lung tissues in the MRSA studya

| Antibiotic | Value for parameter:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (μg · h/ml) | AUC/MIC (h) | AUC > MIC (μg · h/ml) | T > MIC (h) | |

| Linezolid | 59.0 | 29.5 | 47.3 | 5.2 |

| Vancomycin | 48.1 | 48.1 | 42.1 | 6.0 |

| Teicoplanin | 24.9 | 50.0 | 21.9 | 5.9 |

MICs against MRSA NUMR 101 were as follows: linezolid, 2; vancomycin, 1; and teicoplanin, 0.5 μg/ml. Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated from arithmetic means of concentrations in lungs (mean values of four animals).

Table 2 shows the pharmacokinetic parameters in lung tissue in VISA infection. In VISA infection, the time for which lung concentrations of the drug remained above the MIC (T > MIC) was the longest for linezolid.

TABLE 2.

Selected pharmacokinetic parameter estimates for antibiotics in lung tissues in the VISA studya

| Antibiotic | Value for parameter:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (μg · h/ml) | AUC/MIC (h) | AUC > MIC (μg · h/ml) | T > MIC (h) | |

| Linezolid | 59.0 | 59.0 | 53.0 | 6.0 |

| Vancomycin | 48.1 | 6.0 | 11.4 | 2.0 |

| Teicoplanin | 24.9 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

MICs against VISA Mu50 were as follows: linezolid, 1; vancomycin, 8; and teicoplanin, 8 μg/ml. Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated from arithmetic means of concentrations in lungs (mean values of four animals).

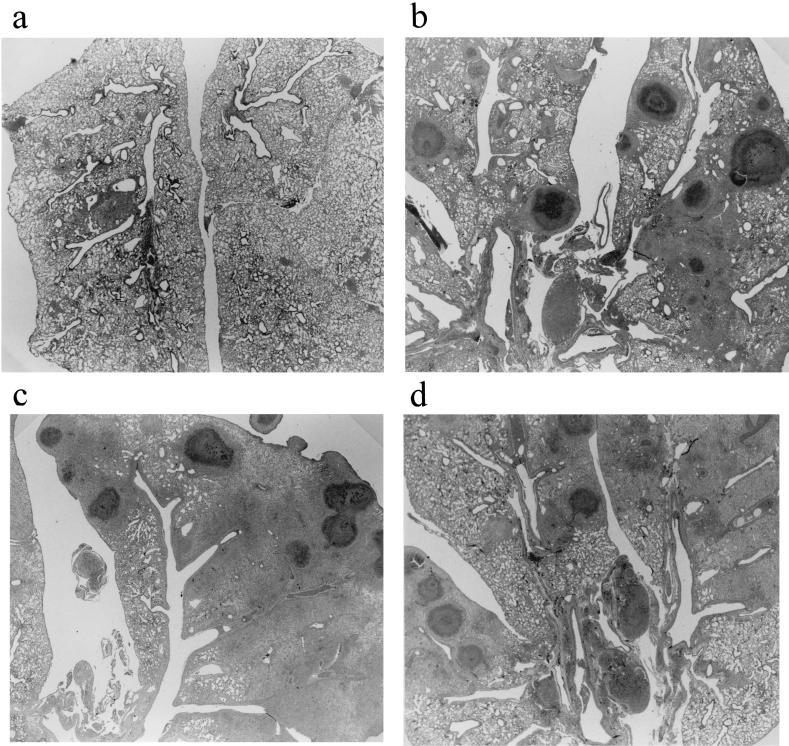

Microscopic examination performed on lung specimens infected with VISA Mu50 at 10 days after treatment revealed lung abscesses consisting of a central zone comprising a bacterial colony with infiltration of acute inflammatory cells (Fig. 3). Findings in the vancomycin (Fig. 3b)- and teicoplanin (Fig. 3c)-treated groups were similar to those in controls (Fig. 3d). The linezolid-treated group (Fig. 3a) exhibited fewer abscesses and less inflammation than did the other groups.

FIG. 3.

Histopathological examination of lung specimens from mice sacrificed 10 days after treatment. Each specimen exhibited typical features of lung abscesses with accumulation of neutrophils inside the bronchial lumen, infiltration of acute inflammatory cells, and exudates in the alveolar spaces (hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification, ×50). (a) Linezolid-treated group; (b) vancomycin-treated group; (c) teicoplanin-treated group; (d) control. Note that the severity of the inflammatory process was less in the linezolid-treated group than in the other groups.

The purpose of this study was to compare the therapeutic efficacy and pharmacokinetic profile of linezolid with those of vancomycin and teicoplanin. For the VISA study, we succeeded in developing lung abscesses in Mu50-infected immunocompromised mice. Sixty percent of these mice were dead at 10 days after infection. Whereas vancomycin and teicoplanin had no effect on survival rate, a significant decrease in mortality was observed with linezolid treatment. These data suggest that VISA is a life-threatening pathogen in immunocompromised hosts and that linezolid is a candidate therapy for VISA infection.

In our model of hematogenous pulmonary infection, linezolid significantly reduced MRSA numbers compared to vancomycin. A previous study of MRSA-associated endocarditis demonstrated the efficacy of linezolid against serious staphylococcal infections in the presence of resistance to other antimicrobials (3). Our present data from the hematogenous infection model are consistent with the previous report. To date, there are no reports of the efficacy of linezolid against VISA infection in vivo. Thus, proof of its efficacy in animal experiments is valuable information.

Craig reported that time above MIC (T > MIC) was a major parameter determining the efficacy of linezolid and that the 24-h AUC/MIC was the primary parameter that correlated with in vivo efficacy of glycopeptides, such as vancomycin and teicoplanin (2). Although the T > MIC of linezolid was similar to that of vancomycin in the MRSA study, bacterial numbers in the MRSA hematogenous infection model were reduced significantly more by linezolid than by vancomycin. These data suggested that the effect of linezolid might rely on AUC > MIC in this model or that the sub-MIC effect of linezolid may be available. Data from the VISA study suggested that T > MIC and AUC > MICs were both highest for linezolid, among the treatment groups. This profile was consistent with the significant improvement in survival rate in the linezolid-treated group.

In conclusion, linezolid clearly reduced bacterial numbers in the MRSA hematogenous infection model and significantly improved the survival rate of immunocompromised mice infected with VISA compared with vancomycin and teicoplanin. The pharmacokinetic profiles of the drugs also reflected the efficacy of linezolid. To our knowledge, this is the first report of in vivo efficacy of linezolid against VISA infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Keiichi Hiramatsu for the generous gift of VISA Mu50. We also thank F. G. Issa for the careful reading and editing of the manuscript.

K. Yanagihara and Y. Kaneko contributed equally to the work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chien, J. W., M. L. Kucia, and R. A. Salata. 2000. Use of linezolid, an oxazolidinone in the treatment of multidrug-resistant gram-positive bacterial infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:146-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craig, W. A. 1997. Postantibiotic effect and the dosing of macrolides, azalides, and streptogramins, p. 27-38. In S. H. Zinner, L. S. Young, J. F. Acar, and H. C. Neu (ed.), Expanding indications for the new macrolides, azalides, streptogramins. Marcel Dekker, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Dailey, C. F., C. L. Dileto-Fang, L. V. Buchanan, M. P. Oramas-Shirey, D. H. Batts, C. W. Ford, and J. K. Gibson. 2001. Efficacy of linezolid in treatment of experimental endocarditis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2304-2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hiramatsu, K., H. Hanaki, T. Ino, K. Yabuta, T. Oguri, and F. C. Tenover. 1997. A methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strain with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 40:135-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng, G. W., R. P. Stryd, S. Murata, M. Igarashi, K. Chiba, H. Aoyama, M. Aoyama, T. Zenki, and N. Ozawa. 1999. Determination of linezolid in plasma by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 20:65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rybak, M. J., E. M. Bailey, and V. N. Reddy. 1991. Clinical evaluation of teicoplanin fluorescence polarization immunoassay. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1586-1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sawai, T., K. Tomono, K. Yanagihara, Y. Yamamoto, M. Kaku, Y. Hirakata, H. Koga, T. Tashiro, and S. Kohno. 1997. Role of coagulase in a murine model of hematogenous pulmonary infection by intravenous injection of Staphylococcus aureus enmeshed in agar beads. Infect. Immun. 65:466-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith, T. L., M. L. Pearson, K. R. Wilcox, et al. 1999. Emergence of vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. N. Engl. J. Med. 340:493-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White, L. O., H. A. Holt, D. S. Reeves, and A. P. MacGowan. 1997. Evaluation of Innofluor fluorescence polarization immunoassay kits for the determination of serum concentrations of gentamicin, tobramycin, amikacin and vancomycin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 39:355-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]