Abstract

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is the causative agent of gonorrhea, a disease that is restricted to humans. Complement forms a key arm of the innate immune system that combats gonococcal infections. N. gonorrhoeae uses its outer membrane porin (Por) molecules to bind the classical pathway of complement down-regulatory protein C4b-binding protein (C4bp) to evade killing by human complement. Strains of N. gonorrhoeae that resisted killing by human serum complement were killed by serum from rodent, lagomorph, and primate species, which cannot be readily infected experimentally with this organism and whose C4bp molecules did not bind to N. gonorrhoeae. In contrast, we found that Yersinia pestis, an organism that can infect virtually all mammals, bound species-specific C4bp and uniformly resisted serum complement-mediated killing by these species. Serum resistance of gonococci was restored in these sera by human C4bp. An exception was serotype Por1B-bearing gonococcal strains that previously had been used successfully in a chimpanzee model of gonorrhea that simulates human disease. Por1B gonococci bound chimpanzee C4bp and resisted killing by chimpanzee serum, providing insight into the host restriction of gonorrhea and addressing why Por1B strains, but not Por1A strains, have been successful in experimental chimpanzee infection. Our findings may lead to the development of better animal models for gonorrhea and may also have implications in the choice of complement sources to evaluate neisserial vaccine candidates.

Keywords: complement, gonorrhea

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is the causative agent of gonorrhea, a disease that is seen only in humans. Gonorrhea is common, with ≈360,000 cases reported in the United States each year and >60 million cases estimated to occur annually worldwide (1). A major limitation in understanding the pathogenesis of gonorrhea (e.g., the growth of gonococci in vivo and the immune response to infection) has been the dearth of animal models that simulate human disease. Attempts to infect or colonize the genital tracts of several animal species, including baboons, pig-tailed macaques, monkeys (rhesus, squirrel, owl, and capuchin), marmosets, rabbits, and guinea pigs with N. gonorrhoeae have been unsuccessful (2). It has not been fully understood why natural infection with N. gonorrhoeae is restricted to humans.

The complement system is an important arm of the innate immune defenses against microbes. In particular, deficiencies of components of the alternative and terminal complement pathways have been associated with recurrent and disseminated neisserial infections (3, 4). The classical pathway of complement is required to initiate complement component C3b deposition and direct killing of gonococci (5), and restriction of classical pathway activation on the bacterial surface provides gonococci a mechanism to resist complement-mediated killing. All of the complement proteins that are necessary to exhibit full complement-related lytic activity are present in cervical mucus at levels that approximate 10% in undiluted human serum (6). Both C3 and C4 in cervical mucus bind to N. gonorrhoeae in vivo, and restriction of complement activation by C3 regulation in vivo mirrors that seen in vitro when organisms are incubated in normal human serum (NHS) (7).

Complement component C4b-binding protein (C4bp) is an important soluble-phase classical pathway regulator. C4bp is a cofactor in factor I-mediated cleavage of C4b to C4d and also accelerates dissociation of C2a irreversibly from the classical pathway C3 convertase (C4b, 2a), thereby restricting the amount of C3 that can be deposited via the classical pathway (8, 9). C4bp (Mr = 570 kDa) is a plasma glycoprotein constituted by seven identical 70-kDa α-chains and a 45-kDa β-chain that are linked by disulfide bridges (10). The α- and β-chains are composed of eight and three complement control protein (CCP) domains, respectively. Three isoforms with different subunit compositions have been identified in human plasma. The major isoform is composed of seven α-chains and one β-chain (α7β1); the remaining two isoforms are α7β0 and α6β1 (11). C4bp has been identified in all mammalian species tested (12). To date, the species most divergent from humans found to contain a protein that is similar in structure and function to the human C4bp α-chain is the barred sand bass, Parablax nebulifer, a bony fish that evolved 300 million years before humans (13).

C4bp binds to several bacterial species and may enhance their pathogenic potential. For example, binding of C4bp to M protein of Streptococcus pyogenes increases resistance to phagocytosis (14). Bordetella pertussis (15), Moraxella catarrhalis (16), and Escherichia coli K1 (17) also bind C4bp and regulate complement activation. We have shown that N. gonorrhoeae evade complement-dependent killing by employing its porin (Por) molecules to bind human C4bp (hC4bp) by means of CCP1 (the N-terminal domain) of the α-chain of C4bp (18). Gonococcal Por makes up 60% of the outer membrane protein content (19). Por is a 34- to 35-kDa protein comprising eight transmembrane loops whose native configuration is a trimer that functions as a selective anion channel (19). Por is an allelic protein consisting of two main isoforms in N. gonorrhoeae, Por1A and Por1B (20). There is moderate antigenic variation between the isoforms, which subdivides them into serotypes or serovars (21, 22). Por1A gonococci frequently cause disseminated disease; Por1B strains usually cause local urogenital disease and pelvic inflammatory disease in women (20, 23, 24).

In this study, we show that the ability of gonococci to resist complement-dependent killing is restricted to human and chimpanzee serum. We hypothesize that the ability of gonococci to bind human and chimpanzee C4bp selectively confers protection to gonococci in these hosts, thereby providing at least one explanation for host restriction of gonococcal disease.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains. N. gonorrhoeae serotype Por1A strains 15253 (25) and FA19 (26) and serotype Por1B strains 1291 (27), FA1090 (28), MS11 (29), and F62 (30) have been described previously. We have shown that hC4bp binds to all of these strains except F62 (31). Isogenic strains that differed only in their Por molecules were constructed from strains FA19 and MS11, and were provided to us by Christopher Elkins and P. Fred Sparling (both of University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) (32). Strain FA6564 resulted from Por1A Por reintroduction into the FA19 (Por1A) background. The isogenic mutant, FA6571, had its Por1A molecule replaced by a Por1B Por molecule. Similarly, strain FA 6616 resulted from Por1B Por reintroduction into the MS11 (Por1B) background, and the isogenic mutant FA6611 had its Por1B molecule replaced by the FA19 Por1A molecule (32). Bacteria were grown in 5% CO2 for 10–12 h on chocolate agar supplemented with Isovitalex equivalent (33) and then suspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 0.15 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2 (HBSS2+) before their use in immunologic assays (see below).

As a comparison, in certain experiments we used an avirulent strain of Yersinia pestis (JG150/KIM5 strain, which is pPCP1+, pCD1+, pMT1+, and Δpgm and hence has all its plasmids but maintains a defect in iron acquisition due to the 102-kb chromosomal pgm deletion) (34). Yersinia were initially grown at 37°C on tryptose or chocolate agar plates overnight and were then inoculated into tryptose broth and again grown overnight with shaking at 37°C. All growth media contained 2mM Ca2+.

Sera and Complement Reagents. Nonimmune NHS was pooled from 10 healthy volunteers with no history of gonococcal infection. Chimpanzee, baboon, and rhesus sera were purchased from Bioreclamation (Hicksville, NY). Rabbit and rat sera were purchased from Cedarlane Laboratories and Advanced Research Technologies (San Diego), respectively. Hemolytic activity of all sera was confirmed by using the total complement hemolytic plate (The Binding Site, Birmingham, U.K.). hC4bp that contained active α7β1 and α6β1 isoforms was purified from plasma (35). Biotinylation of hC4bp was carried out before measurement of C4bp binding to organisms by flow cytometry (31) (see below). ImmunoPure NHS-LC biotin (Pierce) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions, employing a 50-fold molar excess of biotin.

Antibodies and Immunochemicals. Rabbit polyclonal Ab against hC4bp (17) was used in Western blotting experiments to detect free C4bp previously bound to gonococci during incubations (see below). Liberated C4bp was disclosed by using anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Sigma). Fab fragments derived from mAb 104, which is specific for CCP1, were used to block C4bp binding to the gonococcal surface in serum bactericidal assays, as described in refs. 18 and 36. Fab with the expected ≈50-kDa fragments were generated by digestion with immobilized papain (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Binding of biotinylated hC4bp was detected by using streptavidin conjugated to FITC (Sigma) at a dilution of 1:50 in HBSS2+.

Flow Cytometry. Because the anti-C4bp Abs currently available to us did not react with C4bp from non-primate species, we used an indirect “inhibition” assay to assess binding of heterologous C4bp to bacteria. Bacteria (108, either N. gonorrhoeae strain 15253 or control Y. pestis KIM) were incubated with 20% (vol/vol) serum of the indicated species in a final volume of 100 μl. hC4bp-biotin (0.3 μg) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. As a control for inhibition of binding of hC4bp-biotin to gonococci, we used human serum. Biotinylated hC4bp that bound to bacteria was detected by using streptavidin-FITC.

Western Blotting. N. gonorrhoeae (108) suspended in HBSS2+ were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 10% (vol/vol) serum from different primate species in a final reaction volume of 100 μl. Bacteria were washed three times in HBSS2+, followed by digestion of bacterial pellets with 4× lithium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer (NuPAGE LDS sample buffer, Invitrogen). Proteins were resolved on NuPAGE 3–8% Tris-acetate gels by using Tris-acetate running buffer (150 V for 4 h). Western blotting was performed as described in ref. 37. Liberated C4bp was detected by using polyclonal anti-C4bp at a dilution of 1 μg/ml in PBS containing 1% BSA.

Serum Bactericidal Testing. Susceptibility of gonococci to complement-mediated killing by serum from different species was surveyed with serum bactericidal assays as described in ref. 33. Briefly, ≈2,000 colony-forming units of bacteria grown to the midlogarithmic phase were suspended in HBSS2+. Serum was added to a final concentration of 10% (vol/vol); the final volume of all reaction mixtures was 150 μl. Twenty-five-microliter aliquots of the reaction mixtures were plated onto chocolate agar plates at time 0 and 30 min. Percent survival was expressed as the percentage of colonies on a plate at 30 min compared with those on the plate at 0 min. To determine whether the addition of hC4bp could rescue gonococci from killing by heterologous serum complement, we first added 5 μg of hC4bp to bacterial suspensions, followed by the sera of the indicated species to a final concentration of 10%. In some experiments, we added 25 μg of Fab 104 to block C4bp binding to the bacterial surface, as described in ref. 18.

Sequencing of Rhesus Macaque C4bp CCP1 and Sequence Alignment. Rhesus macaque liver cDNA was purchased from Biochain (Hayward, CA). CCP1 of rhesus C4bp was amplified by using primer pair 5′-TCTTCCAAATGACCTTGATCGCTG-3′ and 5′-GGCTTGGTCTCCAAACGCCTATT-3′. The PCR product was sequenced at the Tufts DNA sequencing facility (Tufts University, Boston). Amino acid sequences of CCP1 of human and chimpanzee C4bp were obtained from the GenBank database (accession nos. M31452 and XM514156, respectively) and were aligned with the deduced amino acid sequence of rhesus macaque C4bp CCP by using the bioedit alignment program.

Results

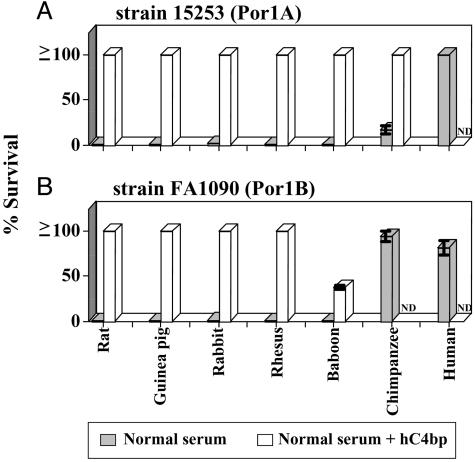

Lack of Serum Resistance of N. gonorrhoeae Using Different Species. We tested two human C4bp-binding strains of N. gonorrhoeae, 15253 and FA1090 (18), for their ability to resist killing by sera from different species. Strains 15253 and FA1090 are representative of Por1A and Por1B serotypes, respectively, and are resistant to killing by human serum complement. Gonococci were incubated at 37°C for 30 min with normal serum from each animal species, as indicated in Fig. 1. We used 10% normal serum, because the activity of complement in human cervical mucus is ≈10% of that in undiluted human serum (6). As expected, both strains 15253 (Por1A) and FA1090 (Por1B) resisted killing (>50% survival) in 10% NHS (Fig. 1). Only strain FA1090 (not 15253) resisted killing by 10% normal chimpanzee serum (NCS). Both strains were killed by 10% serum from rat, guinea pig, rabbit, rhesus, and baboon. Three additional gonococcal strains that bound hC4bp and were resistant to NHS: FA19 (Por1A) and 1291 as well as MS11 (both Por1B) showed similar patterns of resistance to animal sera, as did strains 15253 and FA1090 (data not shown), where only the Por1B strains resisted killing by NCS. These results correlate with previous observations that chimpanzee is the only animal species other than humans where urethral infections can be sustained (38, 39). Y. pestis, the causative agent of plague, which affects a wide array of animals, including rodent, lagomorph, and primate species, was also tested for its ability to resist killing by NHS and normal rat serum. In contrast to N. gonorrhoeae, we found that Y. pestis was capable of fully resisting killing (100% survival) by concentrations of rat serum as high as 50%.

Fig. 1.

Survival of N. gonorrhoeae in nonimmune normal sera from different species, and the protective effect of purified hC4bp to prevent killing of gonococci by non-human sera. Gonococci were incubated with 10% (vol/vol) normal sera at 37°C for 30 min. Bacterial mixtures were plated on chocolate agar at time 0 and 30 min. Results (mean ± SD of duplicate experiments) are expressed as percentage of gonococcal colony-forming units surviving in the presence of sera at 30 min compared with 0 min (gray bars). The effects of adding 5 μg of purified hC4bp to the animal sera that could kill gonococci are shown by the open bars. (A) Survival of gonococcal strain 15253 (serotype Por1A). (B) Survival of Por1B strain FA1090. ND, not done.

Human C4bp Rescues N. gonorrhoeae from Killing by Non-Human Sera. An important mechanism that enables gonococci to resist complement-mediated killing by NHS is the binding of complement regulatory proteins such as C4bp and factor H. We have shown previously that the Por molecule of gonococci can bind C4bp in human serum. We hypothesized that N. gonorrhoeae did not bind C4bp from non-human species, thus rendering them susceptible to killing by these sera. To test this hypothesis, we added hC4bp at physiologic concentrations (250 μg/ml) to the bactericidal reaction mixtures containing sera from other species. The addition of hC4bp rescued both gonococcal strains (15253 and FA1090) from killing by sera from rat, guinea pig, rabbit, rhesus, and baboon (Fig. 1) that had previously been shown to be bactericidal. In addition, Por1A strain 15253 was also rescued when hC4bp was added to chimpanzee serum (Fig. 1 A). As a control, we used gonococcal strain F62, which does not bind hC4bp; this strain showed no increase in survival when hC4bp was added to heterologous sera (data not shown).

The concentration of hC4bp required to protect gonococci from killing by rat serum was 400 μg/ml (92 ± 4% survival of gonococci). hC4bp at 200 μg/ml did not protect gonococci, suggesting a reduced ability of hC4bp to interact with rat C4b (the physiologic range of C4bp concentration in human serum is 200–300 μg/ml).

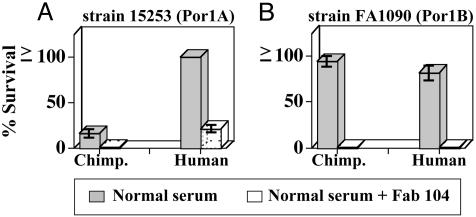

Inhibiting Chimpanzee C4bp Binding to N. gonorrhoeae Results in a Serum-Sensitive Phenotype. Having shown that hC4bp could rescue gonococci from killing by other animal sera, we sought to determine whether the ability of gonococci to resist chimpanzee serum was also related to C4bp binding. Previously, we had used Fab fragments derived from mAb 104 (Fab 104) to block binding of hC4bp to gonococci (18). We confirmed that mAb 104 also bound chimpanzee C4bp (cC4bp) by Western blot (data not shown). We used Fab 104 to block binding of cC4bp in chimpanzee serum and hC4bp in NHS (used as a control) to gonococci and performed a serum bactericidal assay that resulted in 100% killing of both gonococcal strains, 15253 and FA1090 (Fig. 2). This result suggested that binding of cC4bp was important in mediating serum resistance of gonococci to NCS. Fab 67 that recognizes CCP4 of hC4bp and does not block binding of hC4bp to gonococci (18) was used as a control and resulted in no enhancement of killing (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of chimpanzee and human C4bp binding to N. gonorrhoeae results in serum killing. A serum bactericidal assay was performed where Fab 104 (25 μg in each reaction mixture) that blocks C4bp binding to gonococci was affixed to organisms before adding normal human or chimpanzee sera. Percent survival of gonococcal strain 15253 (expressing Por1A) (A) and strain FA1090 (expressing Por1B) (B) is shown for human and chimpanzee sera in the absence (gray bars) and presence (open bars) of Fab 104. Data shown represent mean ± SD of duplicate experiments.

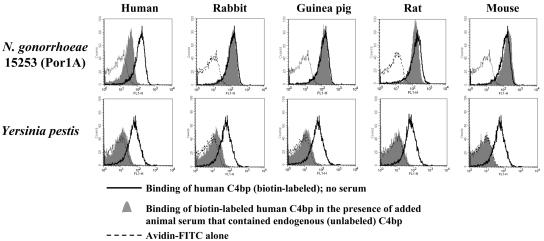

Binding of Non-Human C4bp to N. gonorrhoeae. Next we examined species specificity of binding of C4bp to N. gonorrhoeae. Because none of the anti-C4bp Abs that were available to us reacted with C4bp from non-primate species, we tested the ability of C4bp in sera from different species to block binding of biotinylated hC4bp to N. gonorrhoeae (by inhibition flow cytometry assay). We interpreted this result as indirect evidence of binding of heterologous species C4bp (or lack thereof) to gonococci. N. gonorrhoeae strain 15253 was incubated with 20% (vol/vol) sera from different species in the presence of 0.3 μg of biotinylated hC4bp (100-μl reaction volume), representing an ≈15-fold molar excess of heterologous C4bp over biotinylated hC4bp. Biotinylated hC4bp that bound to 15253 in the presence of the different sera was measured by flow cytometry using streptavidin-FITC (Fig. 3 Upper). We found that endogenous C4bp in rabbit, guinea pig, rat, and mouse sera did not inhibit binding of biotinylated hC4bp to gonococci, suggesting that C4bp from these species does not bind to N. gonorrhoeae. As a control in this experiment and to validate the assay, we used NHS to block binding of biotinylated hC4bp. As indicated above, Y. pestis, the causative agent of plague, was highly resistant to killing by rat and human serum. We hypothesized that Y. pestis would bind C4bp from a wide array of animal species. As seen in Fig. 3 Lower, endogenous C4bp from human, rabbit, guinea pig, rat, and mouse sera completely blocked binding of biotinylated hC4bp to Y. pestis, indicating that C4bp from these species bind to Y. pestis, thereby inhibiting hC4bp binding. These results also provide insight into the putative mechanism of evasion of complement-mediated killing by Y. pestis.

Fig. 3.

Binding of non-human C4bp to N. gonorrhoeae and Y. pestis was measured by inhibition flow cytometry (one representative experiment is shown of two separate experiments performed). N. gonorrhoeae strain 15253 (Upper) and Y. pestis KIM strain (Lower) were each incubated with 10% (vol/vol) human, rabbit, guinea pig, rat, or mouse sera for 10 min at 37°C, followed by the addition of 0.3 μg of biotinylated hC4bp. Biotinylated hC4bp that bound to bacteria was detected with streptavidin-FITC.

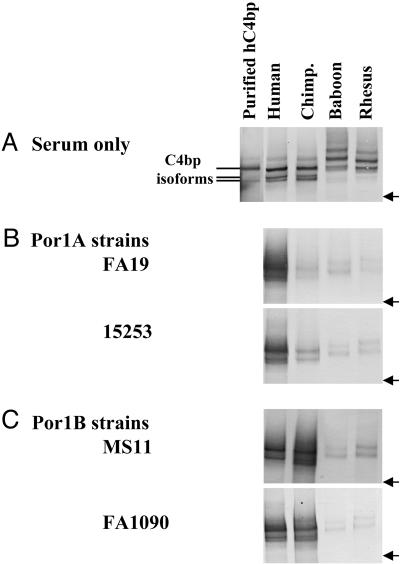

We also tested direct binding of C4bp from different primate species to N. gonorrhoeae by Western blotting. We chose four serum-resistant strains of N. gonorrhoeae that bound hC4bp (18), two belonging to the Por1A serotype (strains FA19 and 15253) and two serotype Por1B strains (strains MS11 and FA1090). N. gonorrhoeae were incubated with 10% serum at 37°C for 30 min. Western blots were probed with polyclonal rabbit anti-hC4bp antibodies after first demonstrating the ability of these antibodies to react with C4bp from all of the primate sera tested (Fig. 4A). We found that only hC4bp bound strongly to Por1A strains (Fig. 4B). Chimpanzee C4bp bound weakly to N. gonorrhoeae strain 15253. Both hC4bp and cC4bp bound well to the Por1B strains (Fig. 4C). These findings correlated well with the ability of strains that bound C4bp from either of the two species to resist serum killing by that species. We also note that Por1A strain 15253 that bound cC4bp weakly showed 17% survival when exposed to 10% NCS (Fig. 1 A), whereas FA19 that did not bind cC4bp at all was 100% killed by NCS.

Fig. 4.

Direct binding of primate C4bp to N. gonorrhoeae. Gonococci were incubated with normal human, chimpanzee, baboon, and rhesus sera, and Western blots were performed with polyclonal rabbit anti-hC4bp. (A) Purified hC4bp (6.25 ng) that contained active α7β1 and α6β1 isoforms (35), normal human, chimpanzee, baboon, and rhesus serum controls at dilutions of 1:200 (vol/vol) were used to ascertain that rabbit anti-hC4bp recognizes all species of primate C4bp tested. A molecular weight marker of 460 kDa is indicated (arrow). (B) Binding of endogenous C4bp in primate sera to two representative Por1A strains, FA19 and 15253. (C) Primate C4bp binding to Por1B strains MS11 and FA1090.

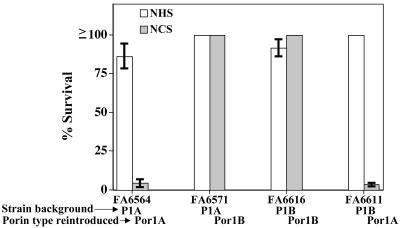

Resistance to Killing by NCS Is Restricted to Por1B-Bearing Gonococci. To confirm that it was cC4bp binding to the Por1B molecule that mediated serum resistance, we performed a serum bactericidal assay with NCS, using isogenic mutant strains that differed only in their Por molecules. As seen in Fig. 5, strains that bore a Por1B (FA6616 and FA6571) molecule were resistant to killing by 10% NCS, independent of strain background. Conversely, strains that bore a Por1A molecule (FA6564 and FA6611) were sensitive to killing by chimpanzee serum. All four strains bound hC4bp (18) and were resistant to killing by NHS. Taken together, these results demonstrate that Por1B molecules that bind hC4bp can also bind cC4bp and resist complement-dependent killing by NCS. In contrast, Por1A-bearing gonococci that bind hC4bp bind cC4bp weakly or not at all and are sensitive to killing by NCS.

Fig. 5.

Por1B-bearing gonococci survive killing by chimpanzee serum. Isogenic Por mutant strains were subjected to the bactericidal action of 10% NHS and NCS. Strains bearing a Por1B molecule (FA6571 and FA6616) were resistant to killing by NCS; those bearing Por1A (FA6564 and FA6616) were sensitive to killing by NCS. Survival was independent of the background structure of the strains. Data shown represent mean ± SD of duplicate experiments.

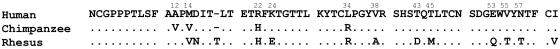

Comparison of Human and Select Primate C4bp Sequences. Alignment of the amino acid sequences of CCP1 of human, chimpanzee, and rhesus macaque C4bp is shown in Fig. 6. Because Por1A binds human C4bp but not chimpanzee C4bp, it may be deduced that the differences in amino acids at positions 12 (A to V), 14 (M to V), 22 (R to H), and 34 (L to R) either alone or in combination are important for Por1A–hC4bp interactions and also determine the species specificity of C4bp binding to Por1A strains. The ability of Por1B strains to bind human and chimpanzee C4bp, but not rhesus C4bp, suggests that amino acid differences other than the four differences between hC4bp and cC4bp are important in the C4bp–Por1B interaction.

Fig. 6.

Amino acid sequence comparison of human, chimpanzee, and rhesus CCP1 of the α-chain of C4bp. Identical amino acid residues are denoted by dots. An insertion (T) in the rhesus macaque amino acid sequence occurs at position 18.

Discussion

Complement forms a key arm of the innate immune system in combating neisserial infections. Evasion of complement-mediated killing is essential for survival of neisseria in vivo (18, 40, 41). We have shown previously that N. gonorrhoeae can bind complement regulatory proteins factor H and C4bp, which are key soluble-phase regulatory molecules of the alternative and classical pathways, respectively, and thus permit resistance of gonococci to complement-mediated killing by NHS (18, 40, 41).

N. gonorrhoeae is a human-specific pathogen. Animal models that have been used to simulate disease in humans by inoculating gonococci into their genital tracts include the chimpanzee (2, 42, 43), which can sustain a gonococcal infection, and more recently the 17-β-estradiol-treated mouse (44). Attempts to infect the genital tracts of baboons, monkeys, rabbits, and guinea pigs have not been successful. McGee et al. (45, 46) showed that gonococci were able to attach to, damage, and invade the oviduct mucosa of chimpanzees but not the oviduct mucosa of baboons. They suggested that, from a chronologic standpoint, susceptibility to gonococcal infection begins at an “evolutionary watershed,” which occurs between baboons and chimpanzees (or between monkeys and great apes) (46). In this report, we have shown that lack of complement regulation on the bacterial surface in sera of other animals is responsible for serum killing of gonococci by sera from these animals. Adding the human classical pathway regulator C4bp to these animal sera rescued gonococci from killing by heterologous sera (Fig. 1). We showed that Por1B strains of N. gonorrhoeae, but not Por1A strains, selectively engaged chimpanzee C4bp to evade killing by NCS. Using isogenic mutant strains of N. gonorrhoeae that differed only in their Por proteins, the specific role of Por was further emphasized independent of the background of the strains (Fig. 5). It is of interest that two gonococcal strains (called Mel and Black) that were used in 1970s to successfully infect chimpanzees were both Por1B strains, whereas a Por1A strain called 2686 consistently failed to infect chimpanzees (47). The Por serovar-specific chimpanzee complement evasion that we report here is consistent with the strain specificity of experimental infections in chimpanzee (48). Another bacterium, Borrelia burgdorferi (the causative agent of Lyme disease) resists complement by using its Erp proteins to bind the alternative pathway regulator, factor H (49). B. burgdorferi can express different Erp proteins, each exhibiting differential affinity for factor H from different animal hosts (50). This variation in phenotype may allow these organisms to exhibit differential complement-mediated resistance in serum from each of the hosts.

Interestingly, we also found that hC4bp could regulate endogenous C4b from other species, despite only limited homology between human and non-primate C4bp; for example, there is only 60% homology at the amino acid level between the α-chain of human and rat C4bp. Despite the ancient nature of the complement system and its long evolution, conservation of critical structure–function relationships persists in certain important complement components. For example, activated forms of the human third (C3b) and fourth (C4b) complement components are cleaved at identical internal sites by enzymatic activity that is present in the plasma or serum of the ancient barred sand bass, P. nebulifer (51).

We have shown previously that the CCP1 domain of the α-chain of C4bp binds to gonococcal Por1A and Por1B. Heparin and a series of mAbs directed against C4bp CCP1 block binding of C4bp to both Por serotypes. However, only the Por1B–C4bp interaction, not the Por1A-C4bp interaction, is diminished by an increase in the ionic strength of the suspending buffer, raising the possibility that the binding site within CCP1 for the two different Por types is not identical. The ability of Por1B, but not Por1A, to bind to chimpanzee C4bp strongly suggests that different amino acids in CCP1 are involved in binding to each of the two Por types. Knowledge of the differences in sequence among human, chimpanzee, and rhesus C4bp can be exploited to determine the amino acids that are critical in enabling C4bp to bind to the two Por types. Our preliminary studies have shown that a recombinant C4bp mutant molecule whose positively charged amino acid cluster at the CCP1/2 interface had been disrupted retained binding to both Por1A and Por1B gonococci (data not shown). This result suggests that the Por-binding region to CCP is distinct from the heparin-binding region, which lies at the interface of CCP1 and CCP2 of the α-chain.

Other mechanisms that may involve increased susceptibility to human gonococcal infection may invoke, for example, other human complement regulatory protein (such as CD46 and factor H) binding by neisserial species. Recently, it has been shown that piliated Neisseria meningitidis cause meningitits more readily in human CD46 transgenic mice (52), although the complement regulatory function of this protein has not been specifically implicated in this enhanced susceptibility. Factor H, which binds to sialylated gonococci (41) in addition to certain unsialylated Por1A-bearing gonococci (40), also enhances serum resistance. Selective binding of transferrin from humans and great apes may be another factor that contributes to species specificity of neisserial infection (53). However, expression of transferrin-binding protein by gonococci is not essential in the murine vaginal infection model (54).

Of note is the difference in the susceptibility to animal sera between the two pathogens, N. gonorrhoeae and Y. pestis. Y. pestis is remarkably resistant to complement or serum-mediated killing from all species tested in this study, which may enhance its pathogenic potential.

The species specificity of complement regulatory protein binding to neisseriae may also serve to explain why rabbit complement is more bactericidal than human complement when vaccine-induced human antibodies are tested for their complement-dependent killing activity. This observation suggests that human complement may be more relevant to use in the evaluation of neisserial vaccine candidates.

In conclusion, we have identified a mechanism that explains the restriction of serum resistance of N. gonorrhoeae to humans and, in some instances, to chimpanzees. Knowledge of factors that permit this neisserial species (and perhaps others) to survive in non-human hosts may lead to development of animal models that will better simulate human disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Björn Dahlbäck (Lund University) for providing mAbs against C4bp. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grants AI 057588 (to E.L.), AI 054544 (to S.R.), and AI 032725 (to P.A.R.); the Swedish Research Council; and the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research.

Author contributions: J.N., S.R., and P.A.R. designed research; J.N., S.R., and S.G. performed research; A.M.B., H.J., E.L., and J.G. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; J.N., S.R., A.E.J., S.G., and P.A.R. analyzed data; and J.N., S.R., E.L., and P.A.R. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: C4bp, C4b-binding protein; Por, porin; CCP, complement control protein; NHS, normal human serum; NCS, normal chimpanzee serum.

References

- 1.Gerbase, A. C., Rowley, J. T., Heymann, D. H., Berkley, S. F. & Piot, P. (1998) Sex. Transm. Infect. 74, Suppl. 1, S12-S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arko, R. J. (1989) Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2, S56-S59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooks, G. F., Israel, K. S. & Peterson, B. H. (1976) J. Infect. Dis. 134, 450-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petersen, B. H., Graham, J. A. & Brooks, G. F. (1976) J. Clin. Invest. 57, 283-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ingwer, I., Petersen, B. H. & Brooks, G. (1978) J. Lab. Clin. Med. 92, 211-220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price, R. J. & Boettcher, B. (1979) Fertil. Steril. 32, 61-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McQuillen, D. P., Gulati, S., Ram, S., Turner, A. K., Jani, D. B., Heeren, T. C. & Rice, P. A. (1999) J. Infect. Dis. 179, 124-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujita, T. & Nussenzweig, V. (1979) J. Exp. Med. 150, 267-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gigli, I., Fujita, T. & Nussenzweig, V. (1979) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76, 6596-6600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillarp, A. & Dahlbäck, B. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 1183-1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hessing, M., Kanters, D., Hackeng, T. M. & Bouma, B. N. (1990) Thromb. Haemost. 64, 245-250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hillarp, A., Wiklund, H., Thern, A. & Dahlbäck, B. (1997) J. Immunol. 158, 1315-1323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krushkal, J., Bat, O. & Gigli, I. (2000) Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 1718-1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berggard, K., Johnsson, E., Morfeldt, E., Persson, J., Stalhammar-Carlemalm, M. & Lindahl, G. (2001) Mol. Microbiol. 42, 539-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berggard, K., Lindahl, G., Dahlbäck, B. & Blom, A. M. (2001) Eur. J. Immunol. 31, 2771-2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nordstrom, T., Blom, A. M., Forsgren, A. & Riesbeck, K. (2004) J. Immunol. 173, 4598-4606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prasadarao, N. V., Blom, A. M., Villoutreix, B. O. & Linsangan, L. C. (2002) J. Immunol. 169, 6352-6360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ram, S., Cullinane, M., Blom, A. M., Gulati, S., McQuillen, D. P., Monks, B. G., O'Connell, C., Boden, R., Elkins, C., Pangburn, M. K., et al. (2001) J. Exp. Med. 193, 281-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blake, M. S. & Gotschlich, E. C. (1986) in Bacterial Outer Membrane as Model Systems, ed. Inouye, M. (Wiley, New York), pp. 377-400.

- 20.Cannon, J., Buchanan, T. & Sparling, P. (1983) Infect. Immun. 40, 816-819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knapp, J. S., Tam, M. R., Nowinski, R. C., Holmes, K. K. & Sandstrom, E. G. (1984) J. Infect. Dis. 150, 44-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith, N. H., Maynard Smith, J. & Spratt, B. G. (1995) Mol. Biol. Evol. 12, 363-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hook, E. W. & Handsfield, H. H. (1999) in Sexually Transmitted Diseases, eds. Holmes, K. K., Sparling, P. F., Mardh, P. A., Lemon, S. M., Stamm, W. E., Piot, P. & Wasserheit, J. M. (McGraw–Hill, New York), pp. 451-466.

- 24.Brunham, R. C., Plummer, F., Slaney, L., Rand, F. & DeWitt, W. (1985) J. Infect. Dis. 152, 339-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamasaki, R., Kerwood, D. E., Schneider, H., Quinn, K. P., Griffiss, J. M. & Mandrell, R. E. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 30345-30351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer, T. F., Mlawer, N. & So, M. (1982) Cell 30, 45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dudas, K. C. & Apicella, M. A. (1988) Infect. Immun. 56, 499-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.West, S. E. H. & Clark, V. L. (1989) Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2, Suppl., S92-S103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maness, M. J. & Sparling, P. F. (1973) J. Infect. Dis. 128, 321-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider, H., Griffiss, J. M., Williams, G. D. & Pier, G. B. (1982) J. Gen. Microbiol. 128, 13-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ram, S., Cullinane, M., Blom, A. M., Gulati, S., McQuillen, D. P., Boden, R., Monks, B. G., O'Connell, C., Elkins, C., Pangburn, M. K., et al. (2001) Int. Immunopharmacol. 1, 423-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carbonetti, N., Simnad, V., Elkins, C. & Sparling, P. F. (1990) Mol. Microbiol. 4, 1009-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McQuillen, D. P., Gulati, S. & Rice, P. A. (1994) in Methods in Enzymology, eds. Clark, V. L. & Bavoil, P. K. (Academic, San Diego), Vol. 236, pp. 137-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goguen, J. D., Yother, J. & Straley, S. C. (1984) J. Bacteriol. 160, 842-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dahlbäck, B. (1983) Biochem. J. 209, 847-856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hardig, Y., Hillarp, A. & Dahlbäck, B. (1997) Biochem. J. 323, Part 2, 469-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Towbin, H., Staehelin, T. & Gordon, J. (1979) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76, 4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kraus, S. J., Brown, W. J. & Arko, R. J. (1975) J. Clin. Invest. 55, 1349-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lucas, C. T., Chandler, F., Jr., Martin, J. E., Jr., & Schmale, J. D. (1971) J. Am. Med. Assoc. 216, 1612-1614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ram, S., McQuillen, D. P., Gulati, S., Elkins, C., Pangburn, M. K. & Rice, P. A. (1998) J. Exp. Med. 187, 671-680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ram, S., Sharma, A. K., Simpson, S. D., Gulati, S., McQuillen, D. P., Pangburn, M. K. & Rice, P. A. (1998) J. Exp. Med. 187, 743-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arko, R., Duncan, W., Brown, W., Peacock, W. & Tomizawa, T. (1976) J. Infect. Dis. 133, 441-447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arko, R. J. & Wong, K. H. (1977) Br. J. Vener. Dis. 53, 101-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jerse, A. E. (1999) Infect. Immun. 67, 5699-5708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McGee, Z. A., Stephens, D. S., Hoffman, L. H., Schlech, W. F., III, & Horn, R. G. (1983) Rev. Infect. Dis. 5, Suppl. 4, S708-S714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGee, Z. A., Gregg, C. R., Johnson, A. P., Kalter, S. S. & Taylor-Robinson, D. (1990) Microb. Pathog. 9, 131-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arko, R. J., Kraus, S. J., Brown, W. J., Buchanan, T. M. & Kuhn, U. S. (1974) J. Infect. Dis. 130, 160-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Evins, G. M. & Knapp, J. S. (1988) J. Clin. Microbiol. 26, 358-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hellwage, J., Meri, T., Heikkila, T., Alitalo, A., Panelius, J., Lahdenne, P., Seppala, I. J. & Meri, S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 8427-8435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stevenson, B., El-Hage, N., Hines, M. A., Miller, J. C. & Babb, K. (2002) Infect. Immun. 70, 491-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaidoh, T. & Gigli, I. (1987) J. Immunol. 139, 194-201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johansson, L., Rytkonen, A., Bergman, P., Albiger, B., Kallstrom, H., Hokfelt, T., Agerberth, B., Cattaneo, R. & Jonsson, A. B. (2003) Science 301, 373-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grey-Owen, S. D. & Schryvers, A. B. (1993) Microb. Pathog. 14, 389-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jerse, A. E., Crow, E. T., Bordner, A. N., Rahman, I., Cornelissen, C. N., Moench, T. R. & Mehrazar, K. (2002) Infect. Immun. 70, 2549-2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]