Abstract

Previous research on proteins that inhibit kidney stone formation has identified a relatively small number of well-characterized inhibitors. Identification of additional stone inhibitors would increase understanding of the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of nephrolithiasis. We have combined conventional biochemical methods with recent advances in mass spectrometry (MS) to identify a novel calcium oxalate (CaOx) crystal growth inhibitor in normal human urine. Anionic proteins were isolated by DEAE adsorption and separated by HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 gel filtration. A fraction with potent inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth was isolated and purified by anion exchange chromatography. The protein in 2 subfractions that retained inhibitory activity was identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight MS and electrospray ionization–quadrupole–time-of-flight tandem MS as human trefoil factor 1 (TFF1). Western blot analysis confirmed the mass spectrometric protein identification. Functional studies of urinary TFF1 demonstrated that its inhibitory potency was similar to that of nephrocalcin. The inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 was dose dependent and was inhibited by TFF1 antisera. Anti–C-terminal antibody was particularly effective, consistent with our proposed model in which the 4 C-terminal glutamic residues of TFF1 interact with calcium ions to prevent CaOx crystal growth. Concentrations and relative amounts of TFF1 in the urine of patients with idiopathic CaOx kidney stone were significantly less (2.5-fold for the concentrations and 5- to 22-fold for the relative amounts) than those found in controls. These data indicate that TFF1 is a novel potent CaOx crystal growth inhibitor with a potential pathophysiological role in nephrolithiasis.

Introduction

Nephrolithiasis remains a public health problem around the world, affecting 1–20% of the adult population (1). Of all types of renal stones, calcium oxalate (CaOx) is the most common composition found by chemical analysis (2). To date, the pathogenic mechanisms of stone formation remain unclear. One long-standing hypothesis is that stone formation is related to intratubular crystal nucleation, growth, and aggregation (3). The urine from patients with nephrolithiasis is commonly supersaturated with calcium and oxalate ions (4), favoring CaOx crystal nucleation and growth (5). Nucleated crystals can be retained in the kidneys of these patients by adhering to renal tubular epithelial surfaces (6, 7). Within the environment of supersaturated calcium and oxalate ions, the stone can then be formed. In contrast, nucleated crystals are not retained in the normal kidney (8). Calculation of the flow rate of renal tubular fluid and the rate of crystal growth in normal subjects suggests that nucleated crystals are eliminated from the normal kidney before they attach to tubular epithelial surfaces (9, 10). Additionally, there are urinary substances known as “stone inhibitors” in the normal renal tubular fluid that inhibit intratubular crystal growth, aggregation, and/or adhesion to renal epithelial surfaces (11). These substances include proteins, lipids, glycosaminoglycans, and inorganic compounds. Abnormality in function and/or expression levels of these molecules, especially proteins, in the urine and renal tubular fluid has been proposed to be associated with stone formation (12–14).

Another hypothesis, first described by Alexander Randall (15), is that the locale of crystal deposition is at a renal interstitium near or at the tip of renal papillae. Randall’s plaques, which contain apatite crystals, are usually found in CaOx stone formers (16). Examination of biopsies obtained during percutaneous nephrolithotomy has shown that apatite crystallization initially occurs in the basement membranes of the thin loop of Henle, then subsequently extends to vasa recta, spreads to the interstitial tissue surrounding inner medullary collecting ducts, and finally extends to the renal papillae (17, 18). Erosion of Randall’s plaques into the urinary space, which is supersaturated with calcium and oxalate ions, can occur and may promote heterogeneous nucleation and formation of CaOx kidney stones (17, 18). Although the CaOx stone formers produce interstitial apatite crystals that form the well-known Randall’s plaques, they do not develop epithelial damage, interstitial inflammation, or fibrosis (17).

CaOx stone formation is also associated with intestinal bypass that promotes hyperoxaluria. Histopathological examination reveals no plaque at the interstitium, but some apatite crystals plugged inside the terminal collecting duct lumens that are associated with epithelial cell damage, interstitial inflammation, and fibrosis (17). Another group of stone formers produce predominantly (>50%) calcium phosphate stones; of these, one-quarter contain brushite (CaHPO4·2H2O), which represents an early phase of calcium phosphate stone formation (19, 20). The degree of brushite supersaturation depends directly on urinary calcium (21), and patients with brushite stones have associated absorptive hypercalciuria type I and distal renal tubular acidosis (20). Brushite stone formers undergo histopathological changes that combine the interstitial plaques of CaOx stone formers with the intratubular apatite plugs found in bypass stone formers; in other words, their histopathology is an amalgam of CaOx and bypass stone disease (19). A nidus of brushite can elicit heterogeneous nucleation or epitaxial growth of CaOx; thus, brushite has been implicated in the formation of both hydroxyapatite [Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2] and CaOx stones (20). On the other hand, many patients with brushite stones initially had CaOx stones (19).

Whether intratubular or interstitial deposition of crystals is the main pathogenic mechanism of renal stone disease remains to be elucidated. It is unlikely that a single mechanism or pathway can explain all forms of kidney stones. Perhaps several mechanisms of stone formation occur in 1 patient. In this study, we have focused our attention on purification, identification and functional analysis of a novel CaOx crystal growth inhibitor and on its potential role in the pathogenic mechanisms of nephrolithiasis. Currently known stone inhibitory proteins are nephrocalcin (22), Tamm-Horsfall protein (23), uropontin (24), inter–α-trypsin inhibitor (bikunin) (25), and urinary prothrombin fragment 1 (crystal matrix protein) (26). Interestingly, these stone inhibitors have similar physical and chemical properties; they are small anionic proteins that bind to calcium and inhibit either growth or aggregation of CaOx crystals. Only a few additional proteins have been identified as inhibitors of stone formation (27–29). In the present study, we have purified and identified a novel CaOx crystal growth inhibitor, namely urinary trefoil factor 1 (TFF1), from normal human urine using conventional biochemical methods and recent advances in mass spectrometry (MS). The presence of TFF1 in the urine was confirmed by Western blot analysis, and its inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth was characterized. Finally, differences in concentrations and relative amounts of urinary TFF1 between patients with idiopathic CaOx stone and normal healthy individuals were evaluated.

Results

Isolation of anionic proteins and screening for potential inhibitors of CaOx crystal growth.

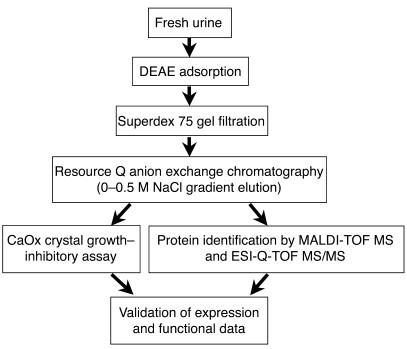

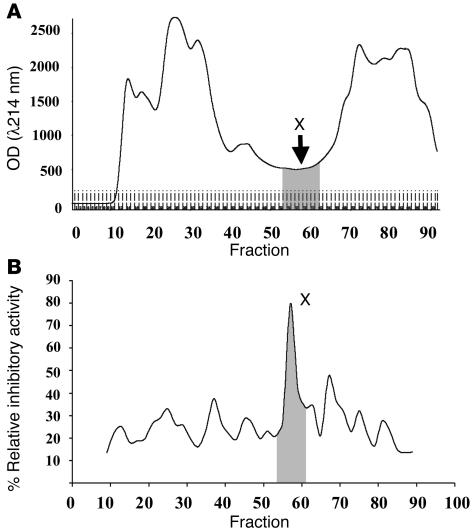

The present study focused on anionic urinary proteins because all proteins known to inhibit CaOx crystal growth are anionic and because urinary proteins may interfere directly with crystal growth and stone formation. The purification methods used in the present study are summarized in Figure 1. Briefly, urine samples obtained from normal healthy donors were adsorbed onto DEAE cellulose and recovered by batch elution (5 l per donor). Anionic proteins were then separated according to size on a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 gel filtration column (Figure 2A). All protein fractions were assayed to measure inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth (Figure 2B). Interestingly, a peak of inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth was present in fractions that had the lowest concentration (lowest OD, λ214 nm). The 8 consecutive fractions that contained this activity were pooled for further analysis and designated fraction X.

Figure 1.

The schematic summary of analytical procedures in the present study. Normal human urinary proteins were purified using DEAE adsorption (isolation of anionic proteins), HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 gel filtration (size separation), and Resource Q anion exchange chromatography with 0–0.5 M NaCl gradient elution (charge separation). The protein in the pooled fraction with potent inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth was identified by MALDI-TOF MS and ESI-Q-TOF MS/MS. Expression and function of the identified proteins were then validated.

Figure 2.

Expression and functional profiles of anionic urinary proteins. (A) After completion of DEAE adsorption, anionic proteins were separated using HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 gel filtration, and peptides were quantitatively analyzed by spectrophotometry at λ214 nm. (B) The inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth of each fraction was measured (see Methods). Fraction X was a low abundant compartment but had a potent inhibitory activity. This pooled fraction was then separated by Resource Q anion exchange chromatography with a 0–0.5 M NaCl gradient elution (charge separation).

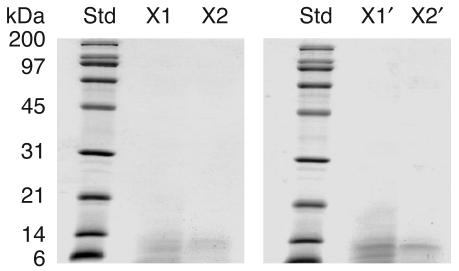

Fraction X was separated further by anion exchange chromatography on a Resource Q column. The bound proteins were eluted with a 0–0.5 M NaCl linear gradient. All subfractions were collected and examined for inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth. Only 2 subfractions, namely subfractions X1 and X2, had strong CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory activity, indicating that they contained the inhibitory activity of the entire fraction X. Proteins in these 2 subfractions were separated further by 12% SDS-PAGE, and a protein band with the same apparent molecular mass (between 6 and 14 kDa) was visualized in both samples (Figure 3). Subfractions X1′ and X2′ corresponded to 2 subfractions, isolated from another preparation of a different donor, to confirm the reproducibility of our purification methods.

Figure 3.

SDS-PAGE of the purified protein with the inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth. Resource Q anion exchange chromatography with a 0–0.5 M linear-gradient salt elution was performed to separate the proteins in fraction X. Of all the subfractions, 2 had potent inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth (subfractions X1 and X2) and were resolved in a 12% SDS-PAGE gel with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 staining (30 μg per lane). Subfractions X1′ and X2′ corresponded to 2 subfractions isolated from a second donor to confirm the reproducibility of our purification methods. Std, standard markers.

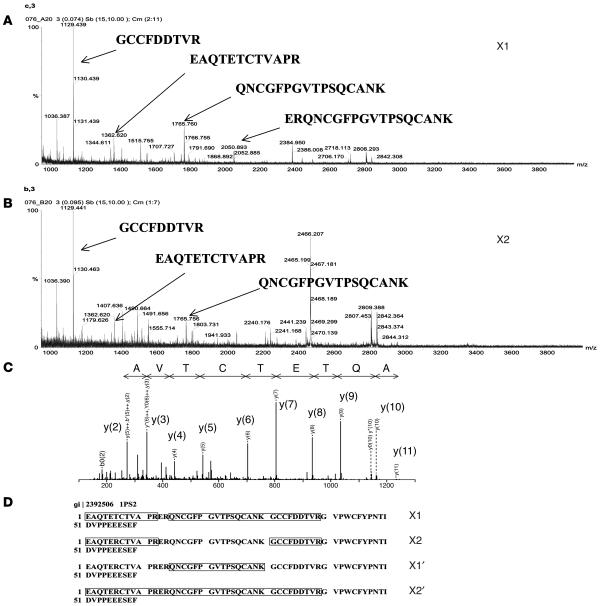

Mass spectrometric identification of human TFF1.

The protein bands detected in subfractions X1, X2, X1′, and X2′ were excised, in-gel tryptic digested, and identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) MS and electrospray ionization–quadrupole–TOF tandem MS (ESI-Q-TOF MS/MS). Figure 4, A and B, illustrates the consistent results obtained from the different protein subfractions. Using the MASCOT search engine (http://www.matrixscience.com), the MALDI and ESI-Q-TOF data obtained from all 4 subfractions were matched significantly with human 1pS2 (gi|2392506, 60 residues), a recombinant form of human TFF1 (Figure 4, C and D). The matching score was highest with recombinant human TFF1 rather than with native human TFF1 because human TFF1 has been submitted to the databases as the precursor form (84 amino acids), not as the mature form (60 amino acids). The only difference between recombinant TFF1 (1pS2) and the native mature form of human TFF1 is at the fifty-eighth residue (serine in 1pS2 versus cysteine in native TFF1) (30). We did not identify the C-terminal tryptic peptide of native TFF1 in any of the protein subfractions of human urine (Figure 4D). This is probably because the C-terminal tryptic peptide of TFF1 can only be identified in negative ion mode. We have therefore identified the native mature form of human TFF1 in the protein subfractions of normal human urine that contain the greatest CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory activity. TFF1 is a small secreted protein expressed predominantly in the gastric mucosa and thought to have an important role in mucosal protection. It has not been implicated previously in normal renal function.

Figure 4.

Identification of TFF1 by MALDI-TOF MS and ESI-Q-TOF MS/MS. (A and B) MALDI mass spectrometric data obtained from subfractions X1 and X2. (C) Tandem mass spectra obtained from ESI-Q-TOF MS/MS were significantly matched with the peptide AQTETCTVA of human 1pS2 (gi|2392506) or TFF1. The fragment ions [y(2), y(3), etc.] generated from MS/MS analyses were numbered according to their position from the C terminus. (D) Using the MASCOT search engine, peptide masses obtained from all subfractions (X1, X2, X1′, and X2′) were significantly matched with 1pS2, the recombinant human TFF1, and the identified residues obtained from MS/MS were labeled.

Validation of mass spectrometric data.

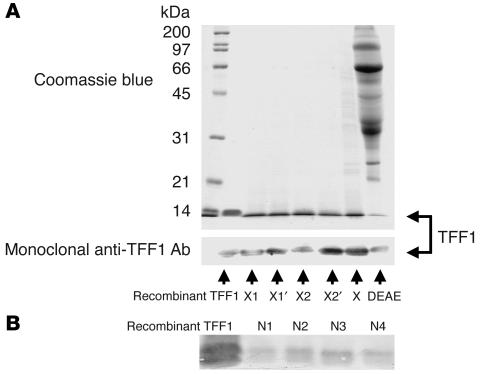

To confirm the identity of human TFF1 in subfractions X1, X2, X1′, and X2′ isolated from 2 normal donors, we performed Western blot analysis using a monoclonal anti-TFF1 antibody. Figure 5A illustrates that Western blotting identified a TFF1 immunoreactive protein band in all 4 subfractions, in the original fraction X, and in the crude anionic sample that migrated with the same apparent molecular mass as recombinant TFF1. These results confirmed the protein identification by MALDI-TOF MS and ESI-Q-TOF MS/MS and indicated that the CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory protein in fraction X and its subfractions is TFF1. The presence of TFF1 in urine was also confirmed in 4 other normal healthy individuals (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Validation of urinary TFF1 expression. Western blot analysis was performed using monoclonal anti-TFF1 antibody, and recombinant TFF1 (2 μg) served as the positive control. (A) Validation was performed for different subfractions, the main fraction X, and crude anionic sample obtained from 2 normal healthy donors (DEAE). (B) Validation was performed for fraction X isolated from 4 normal donors (N1–N4), indicating consistent expression of urinary TFF1 in normal human urine. In each lane, 30 μg total protein was loaded.

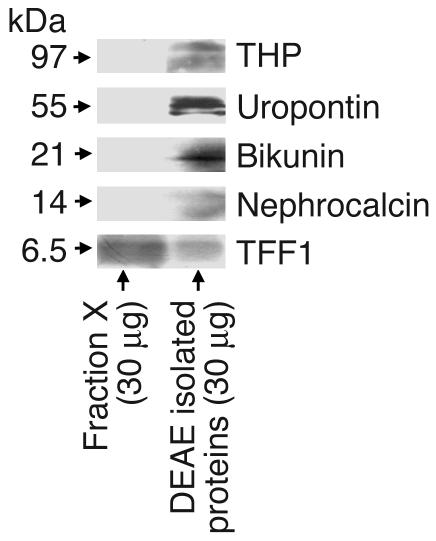

Absence of known stone inhibitors in the urinary TFF1 fraction.

Because the purification of urinary TFF1 in the present study used methodology similar to that employed previously for the purification of other stone inhibitors, particularly nephrocalcin and uropontin (24, 31), we performed Western blot analyses of fraction X to examine whether nephrocalcin, uropontin, bikunin, and Tamm-Horsfall protein were present or contaminated in the purified urinary TFF1 fraction. Figure 6 clearly illustrates that these stone inhibitors were detected only in the total anionic protein fraction, not in the purified fraction X, whereas TFF1 was present in both fraction X and the total anionic protein fraction.

Figure 6.

Purity of isolated urinary TFF1. Western blot analyses of the purified protein were performed to examine whether nephrocalcin, uropontin, bikunin, and Tamm-Horsfall protein (THP) were present as contaminants in the purified urinary TFF1 fraction. The data clearly demonstrate that these stone inhibitors were detected only in the total anionic protein fraction, not in the purified fraction X, whereas TFF1 was present in both fraction X and the total anionic protein fraction.

Characterization of the inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 against CaOx crystal growth.

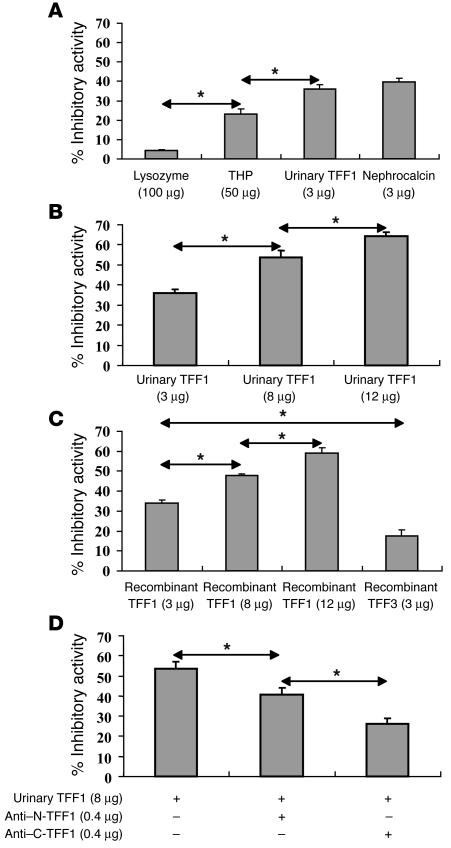

CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory activity of TFF1 purified from human urine was compared with that of known protein inhibitors of crystal growth. Nephrocalcin, a potent CaOx crystal growth inhibitor, was used as a positive control, whereas lysozyme, a protein without Ca2+-binding activity, was used as a negative control. Figure 7A shows the relative inhibitory activities of lysozyme, Tamm-Horsfall protein, nephrocalcin, and urinary TFF1. As expected, nephrocalcin had the most potent inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth, which was consistent with data reported previously (32, 33). Interestingly, the inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 was very similar to that of nephrocalcin (36.1% ± 2.0% versus 39.8% ± 1.9% relative inhibitory activity) when an equal amount of protein was used (3 μg). Tamm-Horsfall protein had much weaker inhibitory activity compared with nephrocalcin and urinary TFF1, even though the total amount of Tamm-Horsfall protein used in this experiment was much greater (50 μg, approximately 16-fold more than nephrocalcin and urinary TFF1). Figure 7B demonstrates that the inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 was dose dependent.

Figure 7.

Characterization of the inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 against CaOx crystal growth. (A) The CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 was similar to that of nephrocalcin when an equal amount of protein was used and more potent than that of Tamm-Horsfall protein, even though a smaller amount of TFF1 was used. Lysozyme was used as a negative control. (B) The inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 was dose dependent. (C) The inhibitory activity of recombinant TFF1 was also dose dependent and comparable with that of urinary TFF1. With an equal amount of protein used, the inhibitory activity of recombinant TFF3 was significantly less (approximately 2-fold) than that of recombinant or urinary TFF1. (D) Incubation of urinary TFF1 with an anti–C-terminal TFF1 antibody significantly reduced the CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory activity of TFF1. The neutralizing effect of anti–C-terminal TFF1 antibody was more potent than that of anti–N-terminal TFF1 antibody. These data indicate that the C terminus of TFF1, which contains multiple glutamic acid residues, is particularly important in mediating the CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory function of TFF1. *P < 0.001. n = 4 per sample.

To confirm that the CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory activity of fraction X was specific to TFF1, the CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory activities of recombinant TFF1 and TFF3, another member in the trefoil factor family, were examined. Figure 7C shows that the CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory activity of recombinant TFF1 was dose dependent and similar to that of purified urinary TFF1 when the same amount of protein was used. The inhibitory activity of recombinant TFF3 was approximately half that of recombinant TFF1 and urinary TFF1.

Further characterization of the inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 against CaOx crystal growth was performed using polyclonal anti–N-terminal and anti–C-terminal TFF1 antibodies to neutralize the inhibitory activity of TFF1. Both antibodies significantly reduced the CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1. Blocking the inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 at its C terminus was more effective than blocking at the N terminus (Figure 7D). These data indicate that the C terminus of TFF1 is particularly important for its inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth.

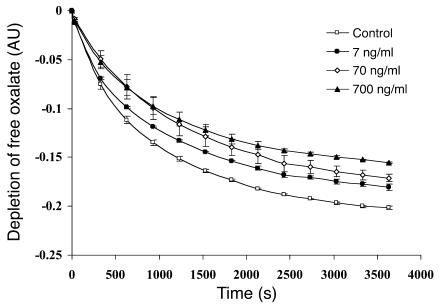

Inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 at physiological levels.

Normal concentrations of urinary TFF1 in 30 normal healthy individuals were measured by ELISA (6.67 ± 0.93 ng/ml). Our results were similar to the data reported recently (7.04 ± 6.43 ng/ml) in 100 normal individuals using radioimmunoassay (34). The protein recovery yield of purification of urinary TFF1 using our protocol was approximately 73.50% ± 17.27%. Because the characterization of the CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 shown in Figure 7 was performed using much higher concentrations of TFF1 than normal, the inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 at physiological concentrations was also examined. Figure 8 shows the kinetics of CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 at of 7, 70, and 700 ng/ml concentrations as well as a control (without TFF1). These data demonstrate significant inhibition of crystal growth by a physiological concentration of TFF1 (7 ng/ml) from 10 minutes of incubation through the end of the assay (1 hour). Additionally, there were significant differences among the 3 concentrations of urinary TFF1 tested.

Figure 8.

Kinetics of the CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 at physiological levels. The inhibitory activities of urinary TFF1 at concentrations of 7, 70, and 700 ng/ml were evaluated to address whether urinary TFF1 at physiological levels could inhibit CaOx crystal growth. The inhibitory assay was performed for a longer duration (up to 1 hour) to simulate the long-term effect of interaction between crystals and low protein concentration during the normal physiological state. Data are presented as the rate of free oxalate depletion. Significant inhibition of crystal growth by a physiological concentration of TFF1 (7 ng/ml) was observed from 10 minutes of incubation through the end of the assay (1 hour). Additionally, there were significant differences among the 3 concentrations of urinary TFF1 tested. n = 3 per group.

Differential levels of urinary TFF1 in patients with idiopathic CaOx kidney stone compared with normal healthy controls.

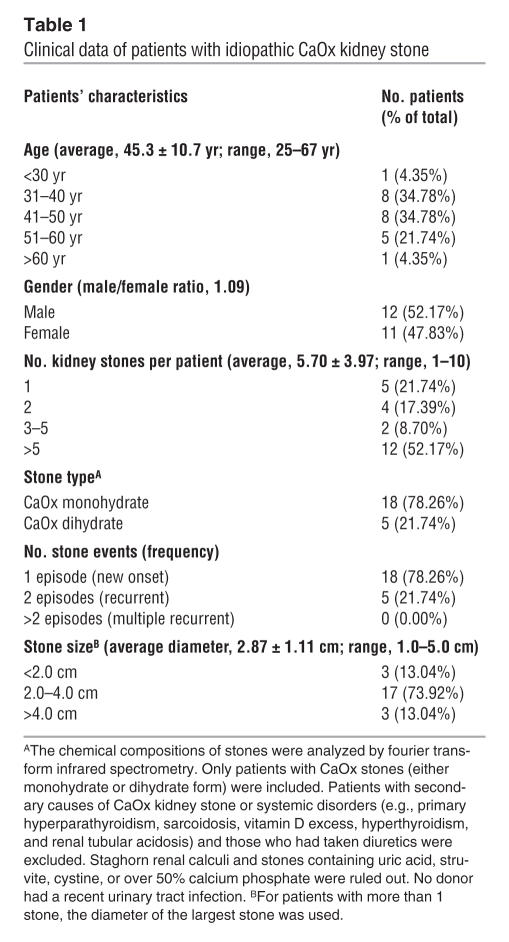

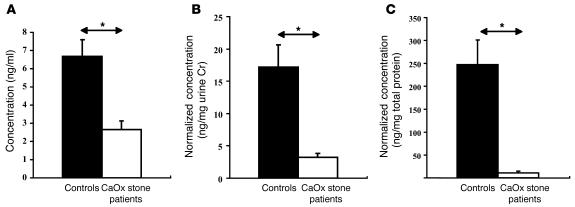

Urinary concentrations of TFF1 in 23 patients (12 males and 11 females) with idiopathic CaOx kidney stones and in 30 normal healthy individuals (14 males and 16 females) were measured using ELISA. Clinical characteristics of patients with idiopathic CaOx kidney stones are summarized in Table 1. Eighteen patients had new onset (first episode) of renal stone disease, whereas the remaining 5 had recurrent (second episode) renal stone disease. Five patients had 1 stone, 4 patients had 2 stones, and the other 14 patients had 5 or more stones. Size of the stones varied from 1.0 to 5.0 cm. Equal amounts of the total anionic proteins isolated from 10 ml urine of each donor were analyzed in this experiment. Figure 9A clearly illustrates that urinary concentrations of TFF1 in patients with idiopathic CaOx kidney stone were significantly lower than those in the normal controls (2.66 ± 0.46 versus 6.67 ± 0.93 ng/ml; P < 0.0001; approximately 2.5-fold difference). After normalization with urine creatinine (Cr; which would represent the total amount of TFF1 excreted within a day), the relative amounts of TFF1 in the urine of CaOx stone formers remained significantly less (3.24 ± 0.62 versus 17.19 ± 3.49 ng/mg Cr; P < 0.0001; approximately 5-fold difference; Figure 9B). This difference remained highly significant after normalization with total protein (11.08 ± 3.21 vs. 247.27 ± 53.68 ng/mg total protein; P < 0.0001; approximately 22-fold difference; Figure 9C).

Table 1.

Clinical data of patients with idiopathic CaOx kidney stone

Figure 9.

Differential urinary levels of TFF1 in CaOx stone formers compared with normal healthy controls. (A) Urinary TFF1 concentrations were measured with ELISA using equal amounts (40 μg) of the total anionic proteins isolated from 10 ml urine of each donor. Urinary concentrations of TFF1 in patients with idiopathic CaOx kidney stone (2.66 ± 0.46 ng/ml; n = 23, 12 males and 11 females) were significantly lower than those in normal healthy individuals (6.67 ± 0.93 ng/ml; n = 30, 14 males and 16 females). (B) After normalization with urine Cr, the relative amounts of TFF1 in the urine of CaOx stone patients remained significantly less (3.24 ± 0.62 versus 17.19 ± 3.49 ng/mg Cr). (C) This difference remained highly significant after normalization with total protein (11.08 ± 3.21 versus 247.27 ± 53.68 ng/mg total protein). *P < 0.0001.

Discussion

CaOx crystal growth inhibitors (proteins, lipids, glycosaminoglycans, and inorganic compounds) have been proposed to play an important role in renal stone disease for several decades (35, 36). While some progress has been made in characterization of these inhibitors, knowledge of proteins that can inhibit stone formation is limited to a relatively small number of proteins. Identification of additional stone-inhibitory proteins was hampered in the past by limitations in protein identification methods, which meant that low abundance components or novel proteins could not be identified without some prior knowledge of their involvement. Exploratory studies using modern technologies to define novel CaOx crystal growth inhibitors are therefore necessary and may lead to better understanding of the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of nephrolithiasis.

In the present study, we have identified human urinary TFF1 as a novel CaOx crystal growth inhibitor by using a combination of conventional biochemical purification methods and recent advances in mass spectrometric protein identification. We initially screened for candidate proteins from a large volume of normal human urine in order to examine all anionic proteins with inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth. This approach allowed us to purify low-abundance proteins that could not be identified in previous studies, in which a smaller volume of urine was utilized (37, 38). The purification was performed systematically, including anionic adsorption, size separation, and finally, charge-density separation. We have focused on fraction X in the present study. This fraction was one among several fractions that had inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth. We have initiated extensive profiling of all these fractions with inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth in a larger number of samples. Characterization and functional analyses of other fractions will have additional significant impact on current knowledge of modulators of stone formation.

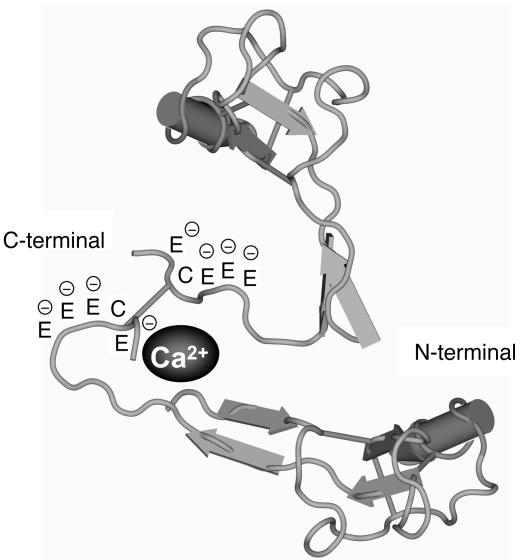

TFF1 is generally known as an estrogen-inducible gene product with 60 amino residues (39–41). It belongs to the trefoil factor family of proteins, is expressed predominately in gastric mucosa, and is synthesized by mucosal epithelial cells (42, 43). It has antiapoptotic and motogenic activities, and its main functions in the gastrointestinal tract are thought to involve maintenance of mucosal integrity and mucosal repair in response to inflammation or injury (44, 45). TFF1 has been identified previously in human urine using radioimmunoassay and Western blotting (34, 46). However, its role in the kidney and urine has not been defined. We now report, for the first time to our knowledge, the CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory function of TFF1 in human urine. In the functional validation studies using anti–C-terminal and anti–N-terminal TFF1-specific antibodies, the former was more effective in neutralizing the inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 against CaOx crystal growth. This supports the contention that the C terminus of TFF1 may be the region of TFF1 responsible for CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory activity. Four of the 6 C-terminal amino acid residues of TFF1 are glutamic acid. We therefore postulate that the glutamic acid residues at the C terminus of urinary TFF1 bind to Ca2+. Previous studies indicated that dimerization of TFF1 plays a key role in both its motogenic and protective/healing properties (47). Our preliminary data showed that the TFF1 dimer had more potent inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth than did the monomeric form at the same molar concentration. This suggests that the C terminus of urinary TFF1 binds to Ca2+ and that its dimerization in the urine (at Cys58–Cys58) (30) facilitates the entrapment of Ca2+ ions (48, 49) and thereby causes CaOx crystal growth inhibition (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The proposed model of Ca2+-binding site in the TFF1 molecules. Based on the functional data in Figure 7D, and because the C terminus contains multiple glutamic residues that are negatively charged, we therefore hypothesize that this area is particularly important in mediating the CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory function of TFF1. Because dimerization usually occurs in the native form of TFF1 (Cys58–Cys58) (30), we also propose that dimerization of TFF1 may facilitate entrapment of Ca2+ ions in this area.

The functional significance of TFF1 was confirmed by evaluating its inhibitory activity at the physiological levels in human urine. Our data clearly demonstrated that urinary TFF1 at the concentration of 7 ng/ml inhibited CaOx crystal growth (Figure 8). The significant inhibitory effect was demonstrated after 10 minutes’ incubation and remained significant through the end of the assay (1 hour). This incubation period was longer than that of the experiments in which much higher concentrations of TFF1 were examined (Figure 7). Moreover, we reported differences in the concentrations and relative amounts (normalized with urine Cr and total protein) of TFF1 in the urine of patients with idiopathic CaOx kidney stone compared with those in the normal urine (Figure 9). The differences (2.5-fold difference in concentration, 5-fold normalized to urine Cr, and 22-fold normalized to total urinary protein; Figure 9) were obvious and indicate that urinary TFF1 plays an important role, at least in part, in the pathogenic mechanisms of CaOx kidney stone disease. However, there are other pathogenic mechanisms and several other stone inhibitors (both known and unknown) that may work together to modulate stone formation, and urinary TFF1 is only one among these multiple factors. To better understand the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of nephrolithiasis, integrative analysis of these different mechanisms in a large cohort study is required.

Methods

The present study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, and by the Ethical Review Committee at Ministry of Public Health, Thailand. Methodologies employed in the present study included DEAE anionic adsorption, gel filtration using HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 (Amersham Biosciences), Resource Q anion exchange chromatography with linear-gradient salt elution (Amersham Biosciences), CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory assay, MALDI-TOF MS, ESI-Q-TOF MS/MS, Western blot analysis, and ELISA. The schema of these analytical procedures is shown in Figure 1.

Subjects.

Urine samples were collected from 30 normal healthy individuals who had not recently taken medication (14 males and 16 females, aged 26.1 ± 2.9 years) and 23 idiopathic CaOx kidney stone patients (12 males and 11 females, aged 45.3 ± 10.7 years). Eighteen patients had new-onset (first episode) renal stone disease, whereas the remaining 5 had recurrent (second episode) renal stone disease. Five patients had 1 stone, 4 patients had 2 stones, and the other 14 patients had 5 or more stones. Stones varied in size from 1.0 to 5.0 cm. The chemical compositions of stones were analyzed by fourier transform infrared spectrometry. Eighteen patients had CaOx monohydrate stones, whereas the remaining 5 had CaOx dihydrate stones. Patients with secondary causes of CaOx kidney stone or systemic disorders (e.g., primary hyperparathyroidism, sarcoidosis, vitamin D excess, hyperthyroidism, and renal tubular acidosis) and those who had taken diuretics were excluded. Staghorn renal calculi and stones containing uric acid, struvite, cystine, or over 50% calcium phosphate were ruled out. No donor had a recent urinary tract infection.

Urine collection.

For the initial screening, isolation and identification of anionic proteins with inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth, we used a large volume of urine samples (5 l each) collected from 2 normal healthy individuals in bottles containing 1% sodium azide over a period of 2–3 consecutive days and stored at 4°C during the entire sample collection period. To validate the initial mass spectrometric data and to confirm the protein identity with Western blot analysis, we used a smaller volume of urine samples (50 ml each) collected from 4 normal healthy individuals. To measure urinary TFF1 levels in all donors (n = 53) by ELISA, only 10 ml urine from each donor was used. The larger volume was processed in the initial screening because we wished to examine all anionic proteins with inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth, including low abundance components. Cell debris and particulate matter were removed from the urine samples by 1,000 g centrifugation at 4°C for 30 minutes, and the supernatant was recovered.

DEAE cellulose anionic adsorption (isolation of anionic proteins).

Because all known urinary proteins that inhibit CaOx crystal growth are anionic (perhaps to bind with Ca2+), we isolated anionic proteins using DEAE adsorption. The urine was diluted 4 times with deionized (dI; 18 MΩ·cm) water, and its pH was adjusted to 7.3. DEAE cellulose (DE-52; Whatman), which had been equilibrated with a buffer containing 0.01 M Tris-HCl and 0.05 M NaCl (pH 7.3), was added into the urine and stirred at room temperature for 30 minutes. The slurry was filtered through a sintered glass filter, and the cake was washed with 0.01 M Tris-HCl in 0.05 M NaCl (pH 7.3) until the filtrate became colorless. The adsorbed proteins were then eluted with 1 l of 0.01 M Tris-HCl in 0.6 M NaCl (pH 7.3). Thereafter, the eluate was dialyzed against 12 l of dI water for 24 hours twice and then lyophilized to reduce the sample volume and to concentrate the proteins.

Gel filtration using HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 Column (size separation).

After DEAE adsorption, size separation of the anionic proteins was performed with a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 gel filtration column (Amersham Biosciences) using a buffer containing 0.15 M NaCl and 0.01 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.3) as a running buffer. The flow rate was 1 ml/min, and absorbance of the eluate was monitored at λ214 nm. The resultant fractions were examined for activity in the CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory assay. Eight consecutive fractions with the lowest OD at λ214 nm — but with the highest inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth — were combined and termed fraction X. After dialysis with dI water, fraction X was lyophilized to reduce its volume.

Anion exchange chromatography using Resource Q column with linear-gradient salt elution (charge separation).

Fraction X was purified by anion exchange chromatography using a Resource Q column (Amersham Biosciences). The column was run in 0.02 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, and the bound proteins were eluted with a 0–0.5 M NaCl linear gradient. All of the resultant subfractions were tested for activity in the CaOx crystal growth–inhibitory assay, and the 2 subfractions with potent inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth (subfractions X1 and X2) were collected. The protein in subfractions X1 and X2 was separated by SDS-PAGE and identified by MS. Salts were removed from the purified protein prior to analysis; the sample was dialyzed with dI water and lyophilized to reduce the volume.

SDS-PAGE and visualization of protein bands.

Aliquots of the concentrated subfractions X1 and X2 were mixed with Laemmli sample buffer and heated at 95°C for 10 minutes. The samples (30 μg per lane) were then resolved in 0.75-mm-thick, 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel using a vertical electrophoresis apparatus (ATTO Corp.). Proteins were then visualized by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (Fluka).

Protein identification by MALDI-TOF MS and ESI-Q-TOF MS/MS.

Visualized protein bands were excised and subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion and identification by both MALDI-TOF MS and ESI-Q-TOF MS/MS (Imperial College London). Peptide matching was performed using the MASCOT search engine (http://www.matrixscience.com) assuming that peptides were monoisotopic, carbamidomethylated at cysteine residues, and oxidized at methionine residues. A mass tolerance was 120 parts per million, and only 1 maximal cleavage was allowed for peptide matching. Probability-based MOWSE (MOlecular Weight SEarch) score was calculated using the formula [–10log(P)], where P was the probability that the observed match was a random event. Peptide matching scores ≥75 (for the MALDI data) and individual ion scores ≥50 (for the Q-TOF or MS/MS data) were considered significant hits.

Anti-TFF1 antibodies.

Murine monoclonal anti-TFF1 antibody was raised in the laboratory of F.E.B. May and used for validation of expression of TFF1 by Western blotting. For characterization of the inhibitory activity of urinary TFF1 against CaOx crystal growth, anti–N-terminal TFF1-specific (catalog no. sc-22501; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) and anti–C-terminal TFF1-specific (catalog no. sc-22502; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) goat polyclonal antibodies were used.

Western blotting.

After SDS-PAGE, separated proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane using a semi-dry transfer apparatus (Amersham Biosciences) at 20 V for 30 minutes. Nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% milk in PBS at room temperature for 1 hour. The membranes were then incubated either with mouse monoclonal anti-TFF1, rabbit polyclonal anti-nephrocalcin (University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine), sheep polyclonal anti–Tamm-Horsfall (catalog no. AB733; Chemicon International), rat monoclonal anti-uropontin (catalog no. MAB3057; Chemicon International), or goat polyclonal anti-bikunin (catalog no. sc-21598; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) antibody at 4°C overnight. Species-specific secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP were then probed at room temperature for 1 hour. Reactive proteins were visualized with either 3,3-diaminobenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich) or SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce Biotechnology Inc.).

Assay to measure inhibitory activity of protein against CaOx crystal growth.

Inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth was measured using the seeded, solution-depletion assay described previously by Nakagawa and colleagues (32). Briefly, CaOx monohydrate crystal seed was added to a solution containing 1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM sodium oxalate (Na2C2O4). The reaction of CaCl2 and Na2C2O4 with crystal seed would lead to deposition of CaOx (CaC2O4) on the crystal surfaces, thereby decreasing free oxalate that is detectable by spectrophotometry at λ214 nm. When a protein is added into this solution, depletion of free oxalate ions will decrease if the protein inhibits CaOx crystal growth. Rate of reduction of free oxalate was calculated using the baseline value and the value after 30-second incubation with or without protein. The relative inhibitory activity was calculated as follows: % Relative inhibitory activity = [(C–S)/C] × 100, where C is the rate of reduction of free oxalate without any protein and S is the rate of reduction of free oxalate with a test protein.

To compare the inhibitory activity of our purified protein to others, lysozyme (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a negative control and nephrocalcin (University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine) was used as a positive control. Tamm-Horsfall protein (University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine) was also examined. Recombinant TFF1 and TFF3 (University of Newcastle) were employed to confirm the specificity of inhibitory activity of our purified protein.

To examine whether site-specific anti-TFF1 antibodies diminish the inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth of the protein in the final 2 subfractions (that were identified as urinary TFF1) and to predict the functional site of urinary TFF1, 0.4 μg anti–N-terminal and anti–C-terminal TFF1-specific polyclonal antibodies were incubated with 8 μg protein sample at 37°C for 1 hour prior to examination with the assay to measure inhibitory activity against CaOx crystal growth.

To examine whether urinary TFF1 at physiological levels could inhibit CaOx crystal growth, urinary TFF1 at concentrations of 7, 70, and 700 ng/ml was evaluated. The inhibitory assay was performed for a longer duration (up to 1 hour) to study the kinetics of TFF1 function at its physiological levels and to simulate the long-term effect of interaction between crystals and low protein concentration during the normal physiological state. The kinetics data were reported as the rate of free oxalate depletion in each condition.

Measurement of urinary TFF1 levels by ELISA.

TFF1 concentrations in the urine of 30 normal healthy individuals and 23 patients with idiopathic CaOx kidney stone were measured by ELISA. Initially, anionic urinary proteins were isolated using DEAE adsorption. The 96-well plate (Nunc; Apogent) was coated with equal amounts of DEAE-isolated anionic proteins (40 μg/well) at 4°C overnight, and nonspecific bindings were blocked with 5% BSA in PBS at room temperature for 2 hours. The plate was washed 3 times with 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS. Anti–N-terminal TFF1 antibody (1:100 diluted with 0.1% BSA in PBS) was used as the primary antibody. After incubation with the primary antibody for 1 hour, the plate was washed 3 times with 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS and incubated with rabbit anti-goat IgG conjugated with HRP (1:1000 diluted with 0.1% BSA in PBS) for 1 hour in the dark. Reactive protein was detected by incubation with o-phenylenediamine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 minutes and quantitated by measuring the absorbance at λ492 nm using an ELISA microplate reader (Anthos HTII; Anthos Labtec Instruments GmbH). Recombinant TFF1 was employed to construct the standard curve, and BSA was used as the negative control.

Statistics.

To compare percent relative inhibitory activity of different samples and to determine differences of urinary TFF1 levels in CaOx stone formers versus normal controls, unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t test were used. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The data were reported as mean ± SD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sutha Sangiambut, Duangporn Chuawatana, Kanittar Srisook, Graham W. Taylor, and Dinah Rahman for their technical assistance; Sombat Borwornpadungkitti, Wattanachai Susangrut, Wipada Chaowagul, and Santi Rojsatapong for urine collection; and Jisnuson Svasti, Chantragan Srisomsap, Polkit Sangvanich, Pa-thai Yenchitsomanus, Somkiat Vasuvattakul, and Sumalee Nimmannit for their invaluable advice and support. This study was supported by the Thailand Research Fund (Senior Research Scholar Program, grant RTA4680017, to P. Malasit) and the Wellcome Trust and Cancer Research, United Kingdom (to F.E.B. May and B.R. Westley). V. Thongboonkerd is supported by Siriraj Preclinic Grant and Siriraj Foundation (D 2362: Surapongchai Fund).

Footnotes

Prida Malasit and Visith Thongboonkerd contributed equally to this work.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: CaOx, calcium oxalate; Cr, creatinine; dI, deiononized; ESI-Q-TOF, electrospray ionization–quadrupole–TOF; MALDI, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization; MS, mass spectrometry; MS/MS, tandem MS; TFF1, trefoil factor 1; TOF, time-of-flight.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Ramello A, Vitale C, Marangella M. Epidemiology of nephrolithiasis. J. Nephrol. 2000;13(Suppl. 3):S45–S50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coe FL, Parks JH, Asplin JR. The pathogenesis and treatment of kidney stones. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992;327:1141–1152. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210153271607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieske JC, Deganello S. Nucleation, adhesion, and internalization of calcium-containing urinary crystals by renal cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1999;10(Suppl. 14):S422–S429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parks JH, Coward M, Coe FL. Correspondence between stone composition and urine supersaturation in nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int. 1997;51:894–900. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandel N. Mechanism of stone formation. Semin. Nephrol. 1996;16:364–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kok DJ, Papapoulos SE, Bijvoet OL. Crystal agglomeration is a major element in calcium oxalate urinary stone formation. Kidney Int. 1990;37:51–56. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lieske JC, Swift H, Martin T, Patterson B, Toback FG. Renal epithelial cells rapidly bind and internalize calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:6987–6991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lieske JC, Deganello S, Toback FG. Cell-crystal interactions and kidney stone formation. Nephron. 1999;81(Suppl. 1):8–17. doi: 10.1159/000046293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finlayson B, Reid F. The expectation of free and fixed particles in urinary stone disease. Invest. Urol. 1978;15:442–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kok DJ, Khan SR. Calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis, a free or fixed particle disease. Kidney Int. 1994;46:847–854. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryall RL. Glycosaminoglycans, proteins, and stone formation: adult themes and child’s play. Pediatr. Nephrol. 1996;10:656–666. doi: 10.1007/s004670050185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coe FL, Nakagawa Y, Asplin J, Parks JH. Role of nephrocalcin in inhibition of calcium oxalate crystallization and nephrolithiasis. Miner. Electrolyte Metab. 1994;20:378–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wesson JA, et al. Osteopontin is a critical inhibitor of calcium oxalate crystal formation and retention in renal tubules. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003;14:139–147. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000040593.93815.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hess B. Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein and calcium nephrolithiasis. Miner. Electrolyte Metab. 1994;20:393–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Randall A. The origin and growth of renal calculi. Ann. Surg. 1937;105:1009–1027. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193706000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Low RK, Stoller ML. Endoscopic mapping of renal papillae for Randall’s plaques in patients with urinary stone disease. J. Urol. 1997;158:2062–2064. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)68153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evan AP, et al. Randall’s plaque of patients with nephrolithiasis begins in basement membranes of thin loops of Henle. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:607–616. doi:10.1172/JCI200317038. doi: 10.1172/JCI17038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bushinsky DA. Nephrolithiasis: site of the initial solid phase. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:602–605. doi:10.1172/JCI200318016. doi: 10.1172/JCI18016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evan AP, et al. Crystal-associated nephropathy in patients with brushite nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int. 2005;67:576–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pak CY, Poindexter JR, Peterson RD, Heller HJ. Biochemical and physicochemical presentations of patients with brushite stones. J. Urol. 2004;171:1046–1049. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000104860.65987.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pak CY. Physicochemical basis for formation of renal stones of calcium phosphate origin: calculation of the degree of saturation of urine with respect to brushite. J. Clin. Invest. 1969;48:1914–1922. doi: 10.1172/JCI106158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakagawa Y, Ahmed M, Hall SL, Deganello S, Coe FL. Isolation from human calcium oxalate renal stones of nephrocalcin, a glycoprotein inhibitor of calcium oxalate crystal growth. Evidence that nephrocalcin from patients with calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis is deficient in γ-carboxyglutamic acid. J. Clin. Invest. 1987;79:1782–1787. doi: 10.1172/JCI113019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hess B. Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein--inhibitor or promoter of calcium oxalate monohydrate crystallization processes? Urol. Res. 1992;20:83–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00294343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shiraga H, et al. Inhibition of calcium oxalate crystal growth in vitro by uropontin: another member of the aspartic acid-rich protein superfamily. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:426–430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atmani F, Khan SR. Role of urinary bikunin in the inhibition of calcium oxalate crystallization. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1999;10(Suppl. 14):S385–S388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryall RL, et al. The urinary F1 activation peptide of human prothrombin is a potent inhibitor of calcium oxalate crystallization in undiluted human urine in vitro. Clin. Sci. (Lond.). 1995;89:533–541. doi: 10.1042/cs0890533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han IS, et al. FKBP-12 exhibits an inhibitory activity on calcium oxalate crystal growth in vitro. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2002;17:41–48. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2002.17.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsujihata M, et al. Fibronectin as a potent inhibitor of calcium oxalate urolithiasis. J. Urol. 2000;164:1718–1723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selvam R, Kalaiselvi P. A novel basic protein from human kidney which inhibits calcium oxalate crystal growth. BJU Int. 2000;86:7–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chadwick MP, Westley BR, May FEB. Homodimerization and hetero-oligomerization of the single-domain trefoil protein pNR-2/pS2 through cysteine 58. Biochem. J. 1997;327:117–123. doi: 10.1042/bj3270117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakagawa Y, Kaiser ET, Coe FL. Isolation and characterization of calcium oxalate crystal growth inhibitors from human urine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1978;84:1038–1044. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91688-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakagawa Y, et al. Urine glycoprotein crystal growth inhibitors. Evidence for a molecular abnormality in calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis. J. Clin. Invest. 1985;76:1455–1462. doi: 10.1172/JCI112124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Worcester EM, Nakagawa Y, Wabner CL, Kumar S, Coe FL. Crystal adsorption and growth slowing by nephrocalcin, albumin, and Tamm-Horsfall protein. Am. J. Physiol. 1988;255:F1197–F1205. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1988.255.6.F1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chenard MP, Tomasetto C, Bellocq JP, Rio MC. Urinary pS2/TFF1 levels in the management of hormonodependent breast carcinomas. Peptides. 2004;25:737–743. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zerwekh JE, Holt K, Pak CY. Natural urinary macromolecular inhibitors: attenuation of inhibitory activity by urate salts. Kidney Int. 1983;23:838–841. doi: 10.1038/ki.1983.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coe FI, Parks JH, Nakagawa Y. Protein inhibitors of crystallization. Semin. Nephrol. 1991;11:98–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakagawa Y, Abram V, Kezdy FJ, Kaiser ET, Coe FL. Purification and characterization of the principal inhibitor of calcium oxalate monohydrate crystal growth in human urine. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:12594–12600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sorensen S, Justesen SJ, Johnsen AH. Identification of a macromolecular crystal growth inhibitor in human urine as osteopontin. Urol. Res. 1995;23:327–334. doi: 10.1007/BF00300022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masiakowski P, et al. Cloning of cDNA sequences of hormone-regulated genes from the MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:7895–7903. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.24.7895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.May FEB, Westley BR. Cloning of estrogen-regulated messenger RNA sequences from human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6034–6040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jakowlew SB, Breathnach R, Jeltsch JM, Masiakowski P, Chambon P. Sequence of the pS2 mRNA induced by estrogen in the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:2861–2878. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.6.2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rio MC, et al. Breast cancer-associated pS2 protein: synthesis and secretion by normal stomach mucosa. Science. 1988;241:705–708. doi: 10.1126/science.3041593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Piggott NH, Henry JA, May FEB, Westley BR. Antipeptide antibodies against the pNR-2 oestrogen-regulated protein of human breast cancer cells and detection of pNR-2 expression in normal tissues by immunohistochemistry. J. Pathol. 1991;163:95–104. doi: 10.1002/path.1711630204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ribieras S, Tomasetto C, Rio MC. The pS2/TFF1 trefoil factor, from basic research to clinical applications. . Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998; 1378:F61–F77. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(98)00016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.May FEB, Westley BR. Trefoil proteins: their role in normal and malignant cells. J. Pathol. 1997;183:4–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199709)183:1<4::AID-PATH1099>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyashita S, Nomoto H, Konishi H, Hayashi K. Estimation of pS2 protein level in human body fluids by a sensitive two-site enzyme immunoassay. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1994;228:71–81. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(94)90278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marchbank T, Westley BR, May FEB, Calnan DP, Playford RJ. Dimerization of human pS2 (TFF1) plays a key role in its protective/healing effects. J. Pathol. 1998;185:153–158. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199806)185:2<153::AID-PATH87>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Polshakov VI, et al. High-resolution solution structure of human pNR-2/pS2: a single trefoil motif protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;267:418–432. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams MA, Westley BR, May FEB, Feeney J. The solution structure of the disulphide-linked homodimer of the human trefoil protein TFF1. FEBS Lett. 2001;493:70–74. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]