Abstract

Objective

To collect population based information on transfusion of red blood cells.

Design

Prospective observational study over 28 days.

Setting

Hospital blood banks in the north of England (population 2.9 million).

Main outcome measures

Indications for transfusion, number of units given, and the age and sex of transfusion recipients.

Participants

All patients who received a red cell transfusion during the study period. Data completed by hospital blood bank staff.

Results

The destination of 9848 units was recorded (97% of expected blood use). In total 9774 units were transfused: 5047 (51.6%) units were given to medical patients, 3982 (40.7%) to surgical patients, and 612 (6.3%) to obstetric and gynaecology patients. Nearly half (49.3%) of all blood is given to female recipients, and the mean age of recipients of individual units was 62.7 years. The most common surgical indications for transfusion were total hip replacement (4.6% of all blood transfused) and coronary artery bypass grafting (4.1%). Haematological disorders accounted for 15.5% of use. Overall use was 4274 units per 100 000 population per year.

Conclusion

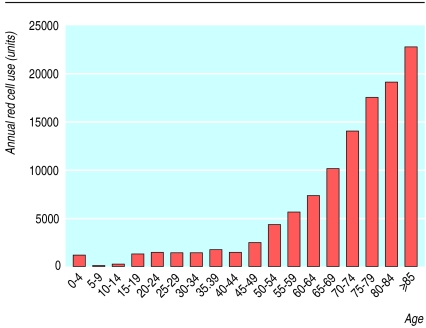

In the north east of England more than half of red cell units are transfused for medical indications. Demand for red cell transfusion increases with age. With anticipated changes in the age structure of the population the demand for blood will increase by 4.9% by 2008.

What is already known on this topic

There have been no systematic population based surveys on use of red cells in the United Kingdom

Studies in France and the United States have shown that more than half of transfused red cells go to surgical patients

What this study adds

In the north of England over half of red cells are given for medical indications

Rates of red cell transfusion rise steeply with advancing age

Small increases in the number of elderly people will have large effects on demand

Introduction

The health service circular Better Blood Transfusion described the action required by NHS trusts and clinicians to improve quality within transfusion practice and highlighted the need for research and review of treatment with blood components.1 Information on the use of red cells and the characteristics of transfusion recipients is limited.2–5 Collection of such data may improve the understanding of fluctuations in demand, help to predict future trends in red cell use, and define the potential value of techniques such as perioperative cell salvage or autologous preoperative deposit.

We undertook a prospective population based survey of the indications for red cell transfusion across the region.

Methods

The north of England is a geographically well defined region with a stable population of 2.9 million. We collected information from all NHS hospital blood banks served by the Newcastle centre using a one page preprinted report form. Data were collected during two 14 day periods in October 1999 and June 2000.

We placed all transfusions for gastrointestinal bleeding, whether the patients were under the care of a surgeon or physician, in a single category as a subdivision of medical indications. Of the remaining medical transfusions, we classified haematological disorders and neonatal top-up or exchange transfusions separately.

We analysed the results by units used within each category, not individual episodes of transfusion. We did not combine information from individual patients who received more than one transfusion during the study period. We obtained estimates of the region's mid-year resident population for 1998, 2003, and 2008 (based on information from the 1991 census) from the Office for National Statistics.

Results

We obtained data from all 18 NHS hospital blood banks across the region. Information on the use of 9848 units was returned; 9774 units were recorded as transfused. Over the study periods the Newcastle centre issued 10 243 to the region's hospitals and accepted 190 returned units. We did not collect data from private and military hospitals in the region; 28 units were issued to these hospitals during the study. The data therefore account for at least 97% of probable red cell use during the four weeks of the study.

A total of 3982 units (40.7% of all transfused blood) were transfused for surgical indications, 5047 (51.6%) for medical indications, and 612 (6.3%) for obstetric or gynaecological indications (table 1). No clinical details were supplied regarding the indication for 133 transfused units (1.4%), and 74 units were reported as wasted. Table 2 shows the distribution of blood used for surgical indications.

Table 1.

Indications for red cell transfusion

| No (% of all transfused and 95% CI) of units (n=9774)

|

Mean (SD) age (years) of recipients*

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Medicine: | ||

| All uses | 5047 (51.6, 50.6 to 52.7) | 64.6 (19.7) |

| Anaemia | 2269 (23.2) | 67.1 (17.1) |

| Haematology | 1514 (15.5) | 61.2 (20.5) |

| Gastrointestinal bleed | 1054 (10.8) | 69.2 (15.5) |

| Other | 148 (1.5) | 55.5 (23.0) |

| Neonatal top up/exchange transfusion | 62 (0.6) | 0 |

| Surgery | 3982 (40.7, 39.7 to 41.7) | 64.1 (18.2) |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology: | ||

| All uses | 612 (6.3, 5.6 to 6.8) | 38.7 (18.0) |

| Gynaecology | 307 (3.1) | 47.7 (19.5) |

| Obstetrics | 305 (3.1) | 29.7 (10.5) |

| No clinical details | 133 (1.4, 1.1 to 1.6) | 60.5 (20.14) |

67.2 (20.1) for all transfusions.

Table 2.

Indications for red cell transfusion in surgical patients

| No (% of all transfused and 95% CI) of units

|

Mean (SD) age (years) of recipients

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Orthopaedics and trauma: | ||

| All | 1358 (13.9, 13.2 to 14.6) | 66.6 (19.1) |

| Total hip replacement | 446 (4.6) | 68.6 (13.3) |

| Fractured neck of femur | 180 (1.8) | 79 (12.0) |

| Total knee replacement | 161 (1.6) | 70.9 (12.4) |

| Road traffic accident | 141 (1.4) | 41.1 (14.7) |

| Other | 430 (4.4) | 63.4 (23.3) |

| General surgery: | ||

| All | 935 (9.6, 9.0 to 10.2) | 62.7 (18.6) |

| Abdominal surgery (excluding colorectal) | 430 (4.4) | 67.1 (13.8) |

| Colorectal surgery | 267 (2.7) | 67.5 (12.7) |

| Other | 238 (2.4) | 49.5 (24.4) |

| Cardiothoracic surgery: | ||

| All | 600 (6.1, 5.7 to 6.6) | 63.7 (17.4) |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 398 (4.1) | 67.6 (9.8) |

| Other | 202 (2.1) | 55.9 (24.8) |

| Vascular surgery: | ||

| All | 448 (4.6, 4.2 to 5.0) | 69.5 (10.8) |

| Emergency repair aortic aneurysm | 226 (2.3) | 68.9 (9.1) |

| Other | 222 (2.3) | 70.2 (12.4) |

| Urology | 254 (2.6) | 66.8 (12.9) |

| Transplant | 167 (1.7) | 43.4 (13.9) |

| Neurosurgery | 113 (1.2) | 59.7 (18.5) |

| Ear, nose, and throat | 57 (0.6) | 63.8 (11.6) |

| Plastic surgery | 50 (0.5) | 46.8 (25.8) |

Demographics of recipients

Information regarding age and sex was available for the recipients of 9537 units, 4701 of which were transfused to female patients (49.3%, 95% confidence interval 48.2 to 50.4).

The average age of a patient receiving an individual unit of blood was 62.7 years (median 67 years, SD 20.1 years). The figure shows age specific rates of red cell use.

Predictions for future red cell use

Using these figures and applying them to population predictions for 2003 and 2008 we have calculated anticipated demand for transfusion assuming age specific transfusion rates remain constant (see bmj.com). We estimate that regional demand will increase by 2.0% in 2003 and 4.9% in 2008.

Discussion

Figures from the study may help in planning effective and efficient use of the available blood supply. The introduction of donor testing for variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease could have a major impact on the numbers of blood donors, with estimates that up to 50% of active donors could be lost. We can predict the effects of blood saving strategies on overall demand for red cells. For example, a 50% reduction of blood use in elective arthroplasty would reduce overall blood requirements by 2.3%. Such a reduction for joint replacement has been documented by comparative audit and review of transfusion thresholds.6 However, the high use for medical indications and the disproportionate rates of transfusion for the very elderly will limit the effect of any strategy directed only at elective surgery.

The potential for blood sparing in medical patients has not been so well defined. A recent survey of patients undergoing chemotherapy has suggested that a third will require blood transfusion.7 Erythropoietin has the potential to reduce this figure, though it is unlikely to be as successful as it has been in patients with anaemia because of renal impairment.

Children are a small part of the transfusion burden in our region. Initiatives to increase safety of blood transfusions for this group would have limited implications for the service as a whole.

Figure.

Age specific transfusion rates (annual red cell use per 100 000 population)

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at hospital blood banks across the Northern region who returned data for the study; Ross Darnell, University of Newcastle statistics service; Audrey Hemsley, National Blood Service, Newcastle Centre; and Professor Steve Proctor, Dr Penny Taylor, and the members of the Northern Region Haematology Group for their pioneering work in establishing population based data collection (a full list of members of the group can be found on bmj.com).

Footnotes

Funding: NBS Clinical Audit department.

Competing interests: None declared.

This is an abridged version; the full version is on bmj.com

This is an abridged version; the full version is on bmj.com

References

- 1.NHS Executive. Better blood transfusion. Leeds: NHS Executive; 1998. (HSC 1998/224). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vamvakas EC, Taswell HF. Epidemiology of blood transfusion [see comments] Transfusion. 1994;34:464–470. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1994.34694295059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiavetta JA, Herst R, Freedman J, Axcell TJ, Wall AJ, van Rooy SC. A survey of red cell use in 45 hospitals in central Ontario, Canada. Transfusion. 1996;36:699–706. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1996.36896374373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook SS, Epps J. Transfusion practice in central Virginia. Transfusion. 1991;31:355–360. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1991.31491213303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathoulin-Pelissier S, Salmi LR, Verret C, Demoures B. Blood transfusion in a random sample of hospitals in France. Transfusion. 2000;40:1140–1146. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40091140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallis JP, Yates B, Siddique S. Role of transfusion audit nurse [abstract 011] Transfus Med. 2000;10 (suppl 1):15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrett-Lee PJ, Bailey NP, O'Brien ME, Wager E. Large-scale UK audit of blood transfusion requirements and anaemia in patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:93–97. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]