Abstract

Purpose: The aim of the study was to determine the extent of use of the Internet for clinical information among family practitioners in New Zealand, their skills in accessing and evaluating this information, and the ways they dealt with patient use of information from the Internet.

Method: A random sample of members of the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners was surveyed to determine their use of the Internet as an information source and their access to MEDLINE. They were asked how they evaluated and applied the retrieved information and what they knew about their patients' use of the Internet. Structured interviews with twelve participants focused in more depth on issues such as the physicians' skills in using MEDLINE and in evaluating retrieved material, their searches for evidence-based information, their understanding of critical appraisal, their patients' use of the Internet, and the ways they handle this use.

Results: More than 80% (294/363) of members in the sample completed and returned the questionnaire. Of these, 48.6% reported that they used the Internet to look for clinical information. Gender and age were more significant in determining use than practice type or location. Information was primarily sought on rare diseases, updates on common diseases, diagnosis, and information for patients. MEDLINE was the most frequently accessed source. Search skills were basic, and abstracts were commonly used if the full text of an item was not readily available. Most reported that up to 10% of patients bring information from the Internet to consultations. Both Internet users and non-Internet users encouraged patients to search the Web. Internet users were more likely to recommend specific sites.

Conclusions: Practitioners urgently need training in searching and evaluating information on the Internet and in identifying and applying evidence-based information. Portals to provide access to high-quality, evidence-based clinical and patient information are needed along with access to the full text of relevant items.

INTRODUCTION

The application of the best available evidence to clinical practice is as important to the family or general practitioner as it is to the specialist. Previous studies of information seeking and use of information by clinicians in family practice focus on the types of questions that arise in family practice and the sources used to answer them [1, 2]. Resources used are mainly textbooks, colleagues, and journal articles held in the office [3, 4]. Family practitioners make little use of medical libraries because of problems of access, lack of skill in using catalogs and databases, and difficulties in applying research literature to clinical situations [5]. The Internet seems to provide a new opportunity to overcome problems of access and provide clinically appropriate information to practitioners. However, while use of the Internet for clinical information has grown substantially in recent years, a pilot study carried out in 2000 suggested that problems of access, lack of skills, and applicability of information remained barriers to effective use of the Internet as a source of information in family practice [6]. The current study was set up to explore these issues further.

Family practitioners are encouraged in the medical literature to use the Internet and the Web as sources of information and as means of access to major databases such as PubMed and the Cochrane Library to enhance their access to an increasingly rich and useful source of clinical information and to promote the use of evidence-based sources [7–9]. The U.K. National Health Services pilot project, the National electronic Library for Health (NeLH), for example, relies on Internet-based access to link practitioners with its extensive evidence-based resources. NeLH is unique in its provision of high-cost/high-value information to practitioners in general practice, and studies evaluating its effectiveness are only just emerging and are inconclusive [10]. Most family or general practitioners do not enjoy access to such high-quality resources, although their professional associations often promote their Web pages as access points to a variety of selected Web-based resources and value-added services, including continuing medical education (CME) resources.

Access to the Internet has been improving rapidly for all professional groups. Recent studies showed a gradual increase in the use of the Internet in both the practice setting and at home with a ceiling around 50%. A 1999 Australian study of general practitioners' use of evidence databases showed 43% of practitioners had access to the Internet (14% at the workplace), and, while 22% were aware of the Cochrane Library, only 4% had used it [11]. A survey in 2000 of general practitioners in Yorkshire found that only half had any access to the Internet and that the most convenient access for a significant proportion of these was at home [12]. Two further New Zealand studies corroborated this figure. The first showed that 72% of currently active general practitioners used the Internet and that 81% of these used it for work-related purposes, in other words, 59% of the respondents currently in medical practice had at some time used the Internet for clinical purposes [13], including email communication. Seventy-one percent of respondents reported that they had patients who referred to information retrieved from the Internet. Half those surveyed reported some concern over the effect of the Internet on the doctor-patient relationship and concern about incorrect information on the Internet. A second New Zealand study reported 56% of New Zealand general practitioners (GPs) had used the Internet in relation to patient care [14]. Awareness of and use of the Cochrane Library had significantly increased compared with the earlier Australian study—42% were aware of it and 15% had used it—but this may have been due to the different context and more education about Cochrane.

A larger study in Switzerland, with only a 55% return rate and no follow-up, reported 75% of respondents had access to the Internet [15]. The number who used it for clinical information was not reported, although 24% had access in the consulting room. While respondents reported that they still preferred textbooks or colleagues as sources of information to resolve problems, 14% reported regularly finding useful information on the Internet. The most-often-used sources were MEDLINE (40%), online journals (21%), and the Cochrane Library (14%). Most information retrieval was outside patient consultation times. Ninety percent of respondents reported patients bringing information from the Internet to consultations, although they indicated that this was still “rare.” Respondents reported that they appraised the quality of Internet-based information on the basis of institution, publishing company, authorship, and time of last update.

A small number of other studies focus primarily on the value of the Internet as a medium for exchange of information between practitioners in “virtual forums” or discussion groups [16], patient's use of information from the Internet and its impact on the doctor-patient relationship [17], and awareness of, access to, and use of the Cochrane Library [18]. In all these studies, access to the Cochrane Library must be assumed to signify access to structured abstracts of systematic reviews only, because subscriber-based access to the full resources of the Cochrane Library is not indicated and is not usual in family practice.

Although a gradual increase in informal use of the Internet to communicate with colleagues and to access sources of clinical information is shown in these studies, little research focuses on the information-seeking skills of practitioners using the Internet or their abilities to search, retrieve, evaluate, and apply evidence-based information. The study reported here investigates the following questions:

What proportion of family physicians in New Zealand use the Internet as a source of information for clinical decision making?

What information do they seek on the Internet?

What resources do they use on the Internet?

How do they access this material?

How skilled are they in retrieving it?

How do they evaluate this material?

What impact does it have on their clinical decision making?

Do patients bring information from the Internet to consultations, and, if so, how do GPs deal with this?

What proportion of GPs recommend the Internet as an information source to patients?

METHOD

The research was carried out between January and August 2001 with the cooperation of the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners (RNZCGP). All medical practitioners who wish to practice family medicine in New Zealand must register their CME activities with an approved institution to retain their practice license, and most register with the college. Using the college membership was believed to be an effective method of reaching a very high percentage of all practicing GPs in New Zealand.

A random sample of 375 members of the college was drawn with the permission of the Professional Development Committee and the chief executive officer. From this sample, 373 potential respondents were approached by a letter requesting them to complete an attached survey. Two follow-up letters were sent to nonrespondents. Six survey forms were returned address unknown, and four people no longer practiced medicine. These changes reduced the sample to 363 possible respondents. The data were entered into and analyzed using an SPSS database.

Twenty respondents who indicated on their survey form that they used the Internet to find clinical information were selected to provide a sample covering a range of age, gender, practice type, and region. Twelve of these agreed to be interviewed and were interviewed using a structured questionnaire to assist in interpreting the data from the survey. The interviews focused on what kinds of information they sought and how they accessed it, what techniques they used to identify and retrieve information on the Web and on MEDLINE, how they evaluated retrieved material, if they actively sought evidence-based resources and how they defined evidence, what they understood by the term critical appraisal, and what impact information they retrieved had on their clinical decision making. They were also asked about their patients' use of the Internet and the ways they handled this. Those who were approached for an interview were offered up to $200 as recompense for their professional time.

RESULTS

Of the 363 members in the sample, 294 (80.9%) completed and returned the questionnaire. Of these, 48.6% (n = 143) reported that they used the Internet to look for clinical information. Most (98.6%, n = 141) had home access, and 36.3% (n = 50) had office access to the Internet. Respondents who did not use the Internet for clinical information made up 51.4% of the sample (n = 151), although some of these did use the Internet for other purposes. Verbal responses in the subsequent interviews were very consistent with the survey responses of each individual, suggesting a high level of validity in the original survey responses. Interview data were used to amplify certain key questions in the survey.

Basic demographics and their correlation with Internet use

Age and Internet use

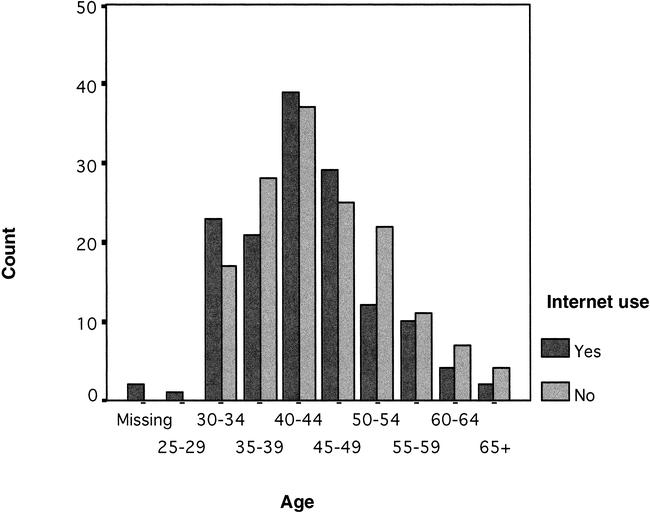

Figure 1 shows an uneven distribution across age categories. A t test showed a mean difference of 4.43 years (P < 0.001). In interviews, most respondents reported that they had been using the Internet for three to five years and could point to some specific factor precipitating use—postgraduate study, a demonstration at a CME meeting or conference, or a perceived need for ready reference sources or sources of patient information that was met by the Internet.

Figure 1.

Age and Internet use

Gender and other factors in Internet use

Use of the Internet was shown to be affected by gender. The percentage of males who responded to the survey was 60.5% (n = 178). The percentage of males using the Internet was 67.1% (n = 96) and the percentage of females 32.8% (n = 47), χ2 = 5.060, df = 1, P = 0.024. No other variables—practice type, location, or categories of practice such as rural or urban and solo or group practice—appeared to have any impact on Internet use.

Type of information sought on the Internet

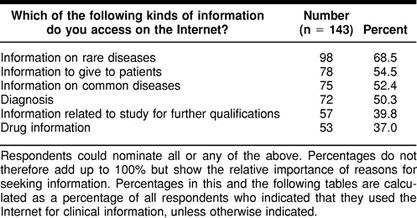

Information about rare diseases was the leading category of information sought, followed by information to give to patients, information on common diseases, and diagnosis. A small number of respondents indicated “other” uses of the Internet such as “advancement of personal knowledge,” “private study,” “update management skills,” “recent developments in medicine,” CME, and other nonmedical uses (shopping, investments, hobbies, etc.).

In interviews, respondents described in more detail what kinds of information they looked for on the Internet and how different sources fitted different needs. This ranged from generally keeping up-to-date with new ideas and treatments to more specific queries—information on rare diseases to assist their own diagnoses or follow-up on diagnoses made by specialists, information relating to conditions that were not responding to routine treatment, information for academic or public presentations or assignments, and better sources of information for patients. An additional reason was to find information in response to material brought by patients, including alternative and complementary treatments (Table 1).

Table 1 Information sought on the Internet

Resources used by general practitioners (GPs) on the Internet and methods of finding resources

Respondents used a range of search engines on the Internet. Yahoo was the most popular search engine (listed by 56.1%), followed by AltaVista (39.8%) and Google (21.2%). A number of respondents indicated that they used a medical search engine and listed MEDLINE or PubMed (19 responses) and Medscape (8 responses). MEDLINE and PubMed also appeared under “Other search engine,” suggesting considerable confusion about the difference between a database and a search engine. A range of medical sites such as BMJ, Cochrane, and Medsafe were also listed as search engines. In interviews, respondents described a wide range of strategies for retrieving information. MEDLINE and PubMed were used by the majority in conjunction with known sites and occasional use of search engines.

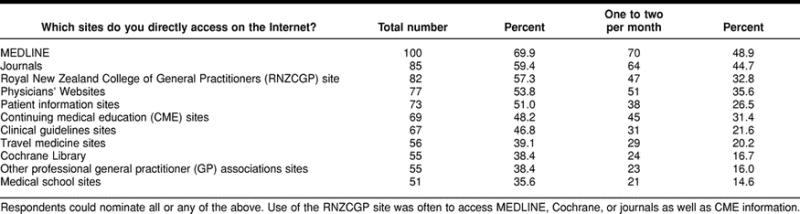

Asked specifically which well-known medical sites or types of medical sites they accessed, respondents indicated the highest use of MEDLINE. This use was primarily through the National Library of Medicine (NLM) PubMed site, although about 1% had access to an Ovid version, usually through involvement with a general practice teaching department (Table 2).

Table 2 Sources accessed on the Internet

Because MEDLINE is available through most other sites accessed by these practitioners—including the RNZCGP site, other general or family practice associations, and medical schools—the use of MEDLINE would seem to be significantly higher overall than the figures suggest.

This inference was reinforced in interviews where the majority of respondents referred to their use of MEDLINE along with leading journal sites (BMJ was the most frequently mentioned), favorite or well-known sites, or gateway sites that could be relied on or were perceived to have filtered information in some way. Although a significant number of survey respondents indicated that they accessed the Cochrane Website (38.4% in total and 16.7% at least monthly), it was clear from interviews that in almost all cases this access would be confined to the level of abstracts only. Other sites that contain systematic reviews of evidence were mentioned by only three interview respondents, but sites with illustrations for patient information or other good sources of patient information were of interest to half the interviewees (n = 6).

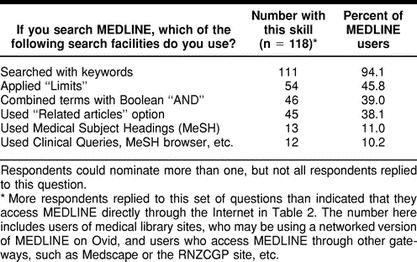

MEDLINE search skills

The majority of users accessed MEDLINE through the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) PubMed interface, which has become a sophisticated, user-friendly interface promoting use of tools such as “Limits” allowing searchers to search by language, date of publication, or type of publication (such as “RCT” or “Review”). Respondents focused primarily on searching by keyword. Only half the MEDLINE users indicated that they searched using Limits. Around a third used the “Related articles” option, and the same number applied the Boolean operator “AND.” Only 10% of MEDLINE users indicated that they employed strategies to refine their search by using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) or the PubMed evidence-based search facility Clinical Queries (Table 3).

Table 3 Searching strategies used on MEDLINE

In the follow-up interviews, it was clear that search skills of respondents were quite varied. Most respondents, while interested in improving their skills, had some basic knowledge of searching and were aware of the need to state the query as precisely as possible, whether they were searching MEDLINE or the Web. When information on rare diseases was sought, keyword searching was obviously less problematic. Techniques on MEDLINE included combining keywords or drug name and side effects and the use of the Boolean “AND” to combine concepts. Referring to MEDLINE, one respondent commented “I haven't been very successful applying Limits so I just put in the terms,” but others indicated that they could use Limits to search for items by language and year of publication and, in one or two cases, by type of publication. One respondent commented that it was not always desirable to limit by date and language when seeking information about alternative or complementary medicine.

Types of publication sought and access to full text

Respondents were asked, if they searched for information by type of publication, to indicate what type of information they sought—randomized controlled trials (RCTs), reviews, or meta-analyses. Many respondents interpreted this question to mean whether they searched for these types of publication using Limits or by visually scanning all items retrieved (a number of interviewees reported using this technique). The question therefore should have contained a longer list of types of publications, including case studies. However, of the three options offered, 107 out of 143 respondents indicated their preferences as follows: reviews, 92.5% (n = 99); RCTs, 44.9% (n = 48); and meta-analysis, 43.8% (n = 46).

Respondents were then asked what action they took once they had found a relevant citation on MEDLINE. Again, it was likely that more than the respondents who indicated they searched MEDLINE responded to this question. Of the 120 who responded to this question, 85% (n = 102) stated that they used the abstract as a guide to contents; 35% (n = 42) retrieved full text off the Internet if possible; 30.8% (n = 37) sent to medical libraries for items; and 2.5% (n = 3) asked drug representatives to obtain items.

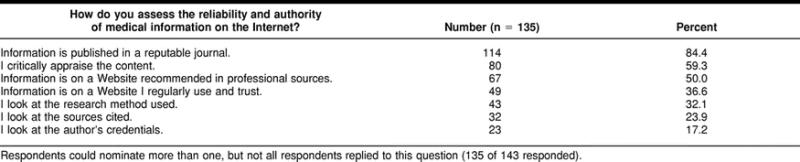

Ways respondents evaluated information retrieved

Asked how they assessed the reliability and authority of medical information on the Internet, respondents listed seven methods (Table 4). Although a relatively large number indicated that they used critical appraisal to evaluate sources, cross-tabulating responses of those who indicated that they critically appraise content with the methods they indicated that they used showed that 64% of this group selected the response “the information is in an article published in a reputable journal,” while only 34% of this group selected the response “I assess the quality of the information by looking at the research methodology” (χ2 = 10.587, P = 0.001). Attention should also be paid to definitions of “critical appraisal” given in the interviews.

Table 4 Methods of evaluating information retrieved

Among the twelve interviewees, five were able to describe how they critically appraised information retrieved from the Internet in terms of the broad principles of critical appraisal as it is formally taught, listing relevance of the study to their own practice, sample size, use of RCTs, and so on. All five had some reason to have knowledge of these principles (e.g., being a tutor for a college's postgraduate training program, joining a guidelines development group in a specialist area, taking a course in appraisal as part of a postgraduate qualification). At the other end of the spectrum were those who did not apply critical appraisal techniques who stated that they were not interested in reading research and did not feel the need to evaluate what they read in this way. A middle group indicated that, while they might look at sample size, they would also look at whether the information fitted with their own clinical experience or confirmed what they already knew. Even those applying more recognizable critical appraisal methods might also take into account clinical experience or what was several times described as “common sense”—perhaps more usually referred to as “consensus” rather than “evidence”-based practice. The two interviewees who focused exclusively on the reputation of a journal or author appeared to have less confidence in their ability to make any independent assessment of content.

Although the survey did not include any questions about evidence-based practice and the need to seek and identify high-quality evidence in information sources, this need was discussed in the interviews. Responses covered a similar range, from those who understood and regularly applied the principles of evidence to those who lacked understanding or knowledge of evidence-based medicine or were actively hostile to the concept.

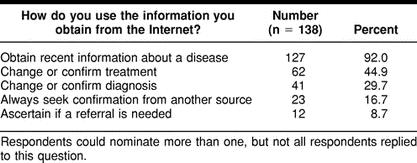

Impact of information from the Internet on clinical decision making

Asked how they would use information from the Internet, respondents indicated that they focused primarily on up-to-date information about disease (Table 5). Of the 138 survey respondents who responded to this question, 115 (approximately 83%) did not indicate that they would seek confirmation of information found on the Internet. However, half the interviewees indicated that they would always seek confirmation from another source, and those who did not seek confirmation outlined situations where use of information from the Internet appeared to have a lower level of risk, for example, if the decision was to cease using a certain therapy, the information was considered to be “Class 1 evidence,” or all other alternatives had been exhausted and, with the patient's consent, a new approach was being tried.

Table 5 How information was used

The information that they were finding on or via the Internet was used by interviewees in a number of ways in addition to assisting with a clinical decision. For many, it was a useful source of information to support their recommendations to patients—information that patients themselves could access. For others, the information opened up new options and new lines of enquiry and provided an alternative channel to specialists' views, an information source that has been dominant in sources sought by New Zealand GPs in the past [12]. Other examples ranged from advice given to patients about exercise in pregnancy, requirements for travel medicine, stoppage of certain treatments used in the past because of evidence in a major Australian study found on the Internet, a change in prescribing habits because of information found on the site of a respected institute, a different drug or plan of care tried, better understanding of the treatment a specialist was using and more confidence in that treatment, referrals made, and new options for an intransigent problem.

Rankings of sources

Survey respondents were asked whether they believed that information in medical journals (print or electronic) was more reliable than information published on Web pages. The majority (73.5%, n = 100) of those responding to the question agreed, and 26.5% (n = 36) disagreed. Respondents were also asked to rank the Internet among a number of other sources that they were known, from previous studies, to regularly use [19]. The sources were ranked by each respondent from 1 (most preferred/most used) to 6 (least preferred/least used). Textbooks were still the preferred source of information, followed by specialists and colleagues and articles in their own collection. Well behind (scored as a first preference by only 4 and 3 persons, respectively), the Internet was ranked higher than medical libraries as a useful source of information by those who responded to this question. Mean scores for each source showed the same rank order.

Patients' use of the Internet and how GPs deal with it

All respondents were asked to complete the section on patients' use of the Internet regardless of whether they themselves used it. A very large majority, 87.8% (n = 258) of all respondents (Internet and non-Internet users) reported that some of their patients now brought information from the Internet to consultations, although most (93%, n = 240) of these 258 respondents estimated that still less than 10% of their patients did so. A further 6.6% (n = 17) estimated between 10% and 20% of patients did so, and only one respondent suggested as high as 20% to 30% of patients did so.

Asked how they responded to patients bringing information from the Internet, the majority (70.4%, n = 207) stated that they take the information into account, but only 38.2% of Internet users and 31.6% (n = 93) of non-Internet users indicated that they would read the information and discuss it at the patient's next visit. Only 14.2% (n = 42) opted for responses “I would ignore the information” or “I would try to explain about the role of clinical experience in decision making.”

Most of the interviewed practitioners recognized the need to deal with this information as a sign of patients' concern and interest in their own health and welcomed this. They were open to discussing the material, would often redirect patients to better sources of information, or tried to talk about the need for “evidence” or, if this was considered too technical, the benefits of the medication they were on. Some would look at Websites brought to their attention by patients or carry the search further.

However, the information or misinformation available on the Internet was described as “terrifying” by one respondent and as “large amounts of very dubious information” by another. The majority of information that patients brought to a consultation was from alternative and complementary medicine sources. More orthodox information was often described as “too general, opinionated, anecdotal, or referred to treatments not available in New Zealand.” Some patients were attempting self-diagnosis and even self-treatment. Although some respondents noted a small amount of useful information being brought to their attention, some of it quite challenging, the majority described information brought by patients as unreliable and inadequate. Patients did not seem to be using the same sources as their physicians.

The proportion of GPs recommending the Internet to their patients

Asked if they would ever recommend the Internet to patients, 55.7% (n = 164) of all respondents would recommend the Internet to their patients as a source of information. Of Internet users, 67% (n = 96) would recommend the Internet to their patients. Of these, 43.4% (n = 62) would recommend patients look at a specific site, and 31.5% (n = 45) would recommend that patients search the Internet for themselves.

Forty-five percent (n = 68) of practitioners who do not use the Internet, and therefore presumably have little knowledge of it or its contents, would recommend the Internet to their patients. This response is higher than expected (z = 1.22; P = 0.111). Of these, 15.2% (n = 23) would recommend a specific site, and 34.4% (n = 52) would recommend patients search for themselves.

The interviews concluded with an additional question concerning training needs that was not included in the questionnaire. Problems noted by respondents that they felt could be addressed by training sessions included: basic computer use; question formulation; search skills in relation to the Web, MEDLINE, and Cochrane; evaluation; and critical appraisal. The need for more assistance and guidance in selecting Websites for regular use—for example, a gateway site with carefully selected resources that would provide better access to quality-filtered information on the Internet—was mentioned by several respondents, and those who had focused throughout on patient information sought a reliable comprehensive source they could routinely use or direct patients to.

DISCUSSION

Use of the Internet is slowly increasing as a means of communication and as a source of information in this community of family practitioners. The results represent a fair snapshot of the situation in 2001. Many of the issues that emerge from this study are foreshadowed in earlier investigations, but the evidence on which to base conclusions and further actions is now clearer and highlights the need for urgent action.

Home-based access to the Internet appears to be driven by routine family use, and growth is related to rates of uptake in the general community. Office access is growing more slowly, but new and cheaper telecommunications packages that make broadband, multichannel Internet access routine for general practitioners for a range of purposes—such as test results, requests to government or private agents for health subsidies, or hospital or specialist referrals—is likely to increase usage. This increase may also help redress gender imbalances, where female practitioners appear hindered in their use at home by other contenders in the household for computers with Internet access. Physical access remains a major barrier to better uptake of Internet-based information sources, but one that is likely to be resolved more easily by market forces than attitudinal or cognitive barriers. Small differences due to age are likely to be eliminated with the passage of time.

The other factors examined in this study, such as practice type and location, do not correlate with significant variation in Internet use. Previous studies have shown that information seeking by clinicians may be driven more by preference for oral over written sources or by cognitive style and self-image as practitioners. Some practitioners see themselves as scientists with a curiosity about research, and others, preferring to focus on patient relationships, make use of information already refereed and summarized by their peers [20]. These considerations may have a considerable impact on the choice of information source on the Internet as well as in other formats.

Although desktop access at point of care is regarded as desirable to increase uptake of quality information in the clinical decision-making process [21–24], previous studies have shown that not all questions can be answered during the patient consultation time. While some questions are best supported by clinical decision support systems at point of care, others can be left until time for reflection is available [25]. Access to resources such as MEDLINE, which is also growing and which continues to be a major source of information for practitioners using the Internet, is not likely to be required during consultations.

Confusion over the difference between a search engine and a database with its own embedded search software and over the various points of access to MEDLINE suggest that knowledge of the source and nature of the information they access is still not common for this group of practitioners. This lack of understanding, along with the basic level of skill in searching MEDLINE, is perhaps a more significant barrier to use of Internet-based sources of information. This problem will not be resolved by market forces in the telecommunications industries but will need proactive intervention by professional associations, colleges, and information professionals if it is to be overcome. Lack of skill in searching MEDLINE and the Web means that the quality of information being retrieved from the Internet by general practitioners is less than optimal. Factors such as reliance on limiting by date of publication to narrow a search rather than use of MeSH and subheadings suggest that respondents may not be finding the best evidence they could. Many respondents recognize the need for higher-level skills to retrieve the most relevant and reliable information.

A further and major concern is the number of respondents who were using abstracts as a source of information on which, at least partially, to base clinical decisions. Abstracts are an unreliable source of information and often overrepresent positive research findings, while oversimplifying negative factors in the findings [26–28]. Access to Cochrane abstracts is perhaps less of an issue, because they are highly structured and informative, and the evidence they present is founded on a well-tested methodology. Even so, document delivery systems to provide access to the full text of articles, Cochrane reviews, and other systematic reviews need to be piloted and evaluated to resolve this difficulty.

Past research has suggested that family practitioners working outside a research environment opt for either internal validation or external validation to evaluate information sources [29]. Internal validation focuses on content, relevance of the study to the intended use of the information, rigor of the research, logic and applicability of conclusions, and so on. External validation relies on the authority of the journal, the publisher, and the institution hosting the Website. Despite the more than 50% of respondents who indicate that they critically appraise information retrieved from the Internet, evidence from the interviews suggests that this term is used loosely by those outside medical schools and research institutes and that the figure is likely to be significantly less than 50%. That a significant proportion of practitioners continue to rely on external validation, despite the fact that internal validation is critical to the methods of evidence-based practice, is a major concern. Furthermore, respondents' lack of ability to appraise the literature confidently and the tendency of some to test all new information against their existing clinical knowledge is worrisome.

Another matter of concern is that there is not greater acceptance of the role of evidence in practice and greater understanding of how evidence can be applied to practice. Responses in interviews to questions about evidence range widely, from those who actively seek evidence and reject anything they do not consider evidence based, including one respondent who has ceased practicing a particular technique because “the evidence does not support it and I cannot charge patients for something which cannot be shown to work,” through to a respondent who states that he has moved away from evidence in recent years, having reached the conclusion that “evidence is important, but so are results. The lack of a statistical answer does not negate an individual response. Medicine needs to accept that the concept of systematic disease has had its day. A more holistic approach is needed.”

While all those interviewed are aware of “evidence” and to some extent expect reliable sources to be evidence based, the majority of responses fall somewhere between the positions outlined above. For most, the evidence-based medicine movement continues to pose a problem. Confronted with the difficulty of applying evidence-based knowledge in daily practice, they explain that, even when they are aware of “evidence,” they have found difficulty in applying it in individual patient cases, because “problems do not present in isolation,” “there is room also for judgment in individual cases,” or “many clinical questions are not answered by evidence.” Difficulties outlined in finding and interpreting evidence could be overcome, as one respondent states, by succinct summaries aimed at providing guidance to GPs. However, this group shows no apparent uptake of the use of guidelines, which could be regarded as a partial answer to their dilemma. Training in the critical appraisal of the evidence as found in systematic reviews as well as original research, combined with training in the judicious application of such evidence, is critical to best practice in family medicine and seems to be emerging as a very urgent need in this group.

Finally, much more discussion of and research into the triad of the patient, the practitioner, and the Internet is necessary. Patients need guidance in searching the Internet, and practitioners, whether they use the Internet or not, need assistance in providing this advice and identifying suitable resources for patient use.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The findings suggest that a need exists for better provision of evidence-based sources of information to general practitioners working outside the systems that provide high-quality information to hospital-based clinicians. The Internet could be a valuable medium for this information, provided that its use is accompanied by training in the identification, use, and application of evidence in practice. Specifically needed are:

improvement in basic information literacy skills for practitioners, including basic computer literacy, question formulation, and searches of the Web, MEDLINE, and Cochrane databases;

training in identifying evidence-based sources, in critical appraisal skills, and in the complex issues surrounding the application of evidence in the clinical setting;

well-developed and well-promoted portals to guide practitioners in the use of Web-based resources to provide access to carefully selected resources;

a patient-information portal site that doctors could either download and print from or direct patients to; although many patient information sites already exists, no one site currently meets all needs; and

a document delivery service so that useful citations retrieved from MEDLINE could be acquired without delays or cost.

Constant evaluation of such services is essential, if they are to be regarded as part of the essential process of bringing evidence into general practice.

REFERENCES

- Covell DG, Uman GC, and Manning PR. Information needs in office practice: are they being met? Ann Intern Med. 1985 Oct; 103(4):596–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman PN, Helfand M.. Information-seeking in primary care: how physicians choose which clinical questions to pursue and which to leave unanswered. Med Decis Making. 1995;15(2):113–9. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven AAH, Boerma EJ, and Meyboom-de Jong B. Use of information sources by family physicians: a literature survey. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1995 Jan; 83(1):85–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman PN, Ash J, and Wyckoff L. Can primary care physicians' questions be answered using the medical journal literature. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1994 Apr; 82(2):140–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen RJ. The medical specialist: information gateway or gatekeeper for the family practitioner. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997 Oct; 85(4):348–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen RJ. The Internet as a source of information for clinical decision-making in family practice. [Web document]. Paper presented at: 8th International Conference of Medical Librarians, 2000; London, U.K. [cited 17 Jun 2002]. <http://www.icml.org/tuesday/user/cullen.htm>. [Google Scholar]

- Haines A, Donald A. Getting research into practice. London, U.K.: BMJ Books, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt JC. Clinical knowledge and practice in the information age: a handbook for health professionals. London, U.K.: Royal Society of Medicine Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Detmer W, Shortliffe E. Using the Internet to improve knowledge diffusion in medicine. Commun ACM. 1997 Aug; 40(8):101–8. [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart C, Yeoman A, Cooper J, and Wailoo A. NeLH pilot evaluation project: final report for NHSIA National electronic Library for Health. Aberystwyth, Wales, U.K.: Department of Information and Library Studies, University of Wales at Aberystwyth, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Young JM, Ward JE. General practitioners' use of evidence databases. Med J Aust. 1999 Jan 18; 170(2):56–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Access to the evidence base from general practice in Northern & Yorkshire region. [Web document]. York, England, U.K.: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2000. <http://www.gpnet.nhsia.nhs.uk/gpnetconnect/NHSnet_benefit_studies.doc.>. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart-Phillips J, Hall K, Herbison GP, Jenkins S, Lambert J, Ng R, Nicholson M, and Rankin L. Internet use amongst New Zealand general practitioners. New Zeal Med J. 2000 Apr; 113(1108):135–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerse N, Arrol B, Lloyd T, Young J, and Ward J. Evidence databases, the Internet, and general practitioners: the New Zealand story. New Zeal Med J. 2001 Mar 9; 114(1127):89–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller M, Grutter R, Peltenburg M, Fischer JE, and Steurer J. Use of the Internet by medical doctors in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2001 May 5; 131(17–18):251–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C, Fox N. General practitioners and the Internet: modelling a “virtual” community. Fam Pract. 1998 Jun; 15(3):211–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd M. General practice on the Internet. Aus Fam Physician. 2001 Apr; 30(4):359–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JM, Ward JE. General practitioners' use of evidence databases. Med J Aust. 1999 Jan 18; 170(2):56–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen RJ. The medical specialist: information gateway or gatekeeper for the family practitioner. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997 Oct; 85(4):348–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen RJ. The medical specialist: information gateway or gatekeeper for the family practitioner. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997 Oct; 85(4):348–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litzelman DK, Dittus RS, Miller ME, and Tierney WM. Requiring physicians to respond to computerized reminders improves their compliance with preventive care protocols. J Gen Intern Med. 1993 Jun; 8(6):311–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobach DF, Underwood HR. Computer-based decision support systems for implementing clinical practice guidelines. Drug Benefit Trends. 1998 Oct; 10(10):48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Persson M, Mjorndal T, Carlberg B, Bohlin J, and Lindholm LH. Evaluation of a computer-based decision support system for treatment of hypertension with drugs: retrospective, nonintervention testing of cost and guideline adherence. J Intern Med. 2000 Jan; 247(1):87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestotnik SL, Classen DC, Evans RS, and Burke JP. Implementing antibiotic practice guidelines through computer-assisted decision support: clinical and financial outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1996 May 15; 124(10):884–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly DP, Rich EC, Curley SP, Kelly JT.. Knowledge resource preferences of family physicians. J Fam Pract. 1990;30(3):353–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada CA, Bloch RM, Antonacci D, Basnight LL, Patel SR, and Patel SC. Reporting and concordance of methodologic criteria between abstracts and articles in diagnostic test studies. J Gen Intern Med. 2000 Mar; 15(3):183–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narine L, Yee DS, Einarson TR, and Ilersich AL. Quality of abstracts of original research articles in CMAJ in 1989. Can Med Assoc J. 1991 Feb; 144(4):449–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winker MA. The need for concrete improvement in abstract quality. JAMA. 1999 Mar 24–31; 281(12):1129–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen RJ. The medical specialist: information gateway or gatekeeper for the family practitioner. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997 Oct; 85(4):348–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]