Abstract

This paper describes a popular, grassroots health crusade initiated by Samuel Thomson (1769–1843) in the early decades of the nineteenth century and the ways the Thomsonians exemplified the inherent contradictions within the larger context of their own sociopolitical environment. Premised upon a unique brand of frontier egalitarianism exemplified in the Tennessee war-hero Andrew Jackson (1767–1845), the age that bore Jackson's name was ostensibly anti-intellectual, venerating “intuitive wisdom” and “common sense” over book learning and formal education. Likewise, the Thomsonian movement eschewed schooling and science for an empirical embrace of nature's apothecary, a populist rhetoric that belied its own complex and extensive infrastructure of polemical literature. Thus, Thomsonians, in fact, relied upon a literate public to explain and disseminate their system of healing. This paper contributes to the historiography of literacy in the United States that goes beyond typical census-data, probate-record, or will-signature analyses to look at how a popular medical cult was both heir to and promoter of a functionally literate populace.

INTRODUCTION

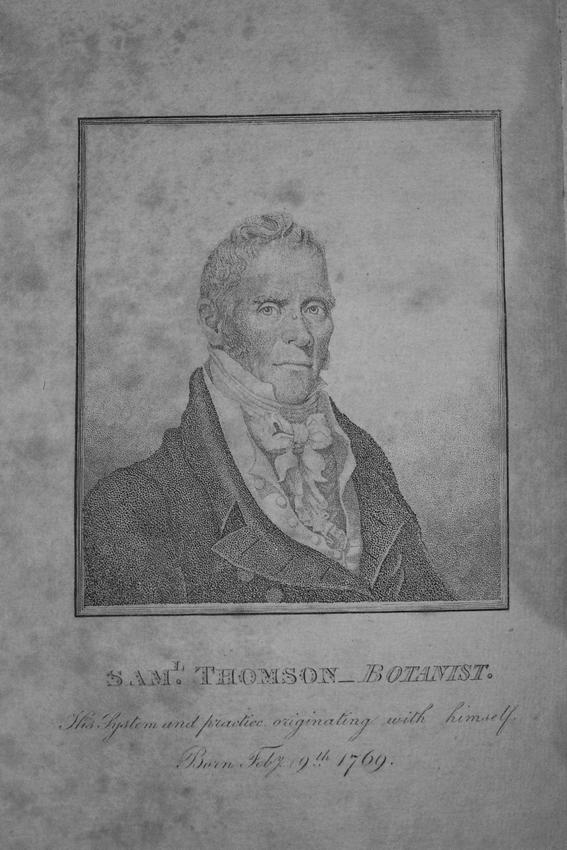

Leader of a grassroots medical movement reflecting the larger social and political environments in which it resided, one colorful, irascible citizen, Samuel Thomson (1769–1843) (Figure 1), utilized the rhetoric of the age to promote a uniquely American form of self-help health care. The populism and egalitarianism that characterized the Jacksonian era was a powerful force in the new republic, and Thomson was able to transform his ideas into a movement, because he effectively portrayed himself as a spokesman for the people's medicine. If, as John William Ward has convincingly argued, Andrew Jackson was a symbol for an age [1], then Thomson became its Hippocrates.†

Figure 1.

Samuel Thomson (1769–1843)

Yet the botanical movement that bore his name was by its very nature full of contradictions. Calling upon common folk of simple means, Thomson himself became wealthy. Believing that any man could be his own physician, Thomson was convinced he alone had unlocked the secrets to healing and health. Chastising regular physicians for their arrogance, Thomson evinced a hubris equaled by few. Indicting the regulars for their monopolistic designs on health care, Thomson jealously guarded his own patent rights and spent an inordinate amount of his time prosecuting real and imagined infractions thereof. Chiding orthodox physicians for their bookish pretensions, Thomson sought to advance his own system through books and journals. This last point holds particular value for understanding a major contradiction within the age itself, a period that venerated intuitive understanding over cultivated knowledge on the one hand and yet saw perhaps the greatest expansion of functional literacy of any American generation before or since.‡

Such juxtapositions immediately raise significant questions: What was the Jacksonian era, and how did it serve as fertile ground for the establishment of the Thomsonian system? What was Thomson's system, and how did he and his agents use features of Jacksonian democracy as the foundation of an effective apologetics that both explained and promoted this grassroots movement? Finally, what did their strategies, successes, and failures tell us about life, liberty, and literacy in the Jacksonian era?

ZEITGEIST OF THE NATION

In March of 1829, Andrew Jackson (1767–1845) rode triumphantly into Washington, DC, to assume the presidency that had eluded him during the 1824 campaign. Born in the backwoods of the South, “Ol' Hickory” was a popular representative of the burgeoning West, a self-taught war hero who seemed to represent a new era in the young republic. Gone were the Virginia gentry and the New England bluebloods who had filled the executive office in the previous six administrations; this was someone different.

The bright and sunny day that dawned on March 4 would illustrate how different it really was. It began predictably enough with Jackson giving a well-spoken, even eloquent, inaugural address in the east portico of the Capitol. But what followed later at the celebration of this people's president showed that this was more than a mere change in personnel. The turnout was huge and the throng enthusiastic in their revelry. The Argus of Western America called it “a proud day for the people” [8]. For many, it was precisely what this nation had been born for, a republic embodying the very essence of egalitarianism, a place where intuitive wisdom and natural talents could receive—and now finally had received—full expression.

Wealthy and prominent Margaret Bayard Smith (1778–1844) knew better. Writing to a friend shortly after the so-called “people's inaugural,” she gave a very different firsthand account. An assemblage, beginning orderly and exhibiting decorum appropriate to the dignity of the affair, soon degenerated first into a massive throng (perhaps as many as 20,000) and then into a howling mob that threatened at least at one point to tear their new leader limb from limb in their orgiastic enthusiasm to shake Ol' Hickory's hand. Fine china was smashed, tapestries ruined, and gardens trampled as country rube jostled with equally crass nouveau riche for a glimpse of their new Mr. President. Several thousand dollars worth of damage resulted from the pandemonium. Smith agreed with the Argus:

[I]t was the people's day, but oh what a day and oh what a people! God grant that one day or other the people do not put down all rule and rulers, [she warned. These] enlightened freemen . . . have been found in all ages and countries where they get the power in their hands, that of all tyrants, they are the most ferocious, cruel, and despotic. The noisy and disorderly rabble in the President's house, [she concluded,] brought to my mind descriptions I had read of the mobs in the Tuileries and at Versailles. [9]

The vision of an anarchistic, French-like revolution conjured up by the Washington socialite was an obvious exaggeration. Nevertheless, Jackson's unshakable belief that virtually anyone could handle the affairs of government spawned a spoils system§ that would not be tamed for another fifty years, leading Justice Joseph Story (1779–1845) to declare that the “reign of King Mob” had been inaugurated [10]. Jackson's election represented the fulfillment of a popular democratic spirit that emerged from complex sociopolitical and socioeconomic forces: western expansion, a widespread agrarian populace, and a broadly diffused fervent American Protestantism built upon a priesthood of all believers. Thus, Jacksonian ideals and ideas emanated from much larger forces than Jackson himself. This zeitgeist of the age extended in different forms and in various degrees of intensity well beyond Jackson's years in office (1829–1837) to the very eve of the Civil War [11].

LIFE AND LIBERTY IN THE JACKSONIAN ERA

That this horrific scene at the Capitol reflected society at-large was not entirely without foundation. Antebellum America was a rough-and-tumble place. Liquor was everywhere, and, in cities, street toughs and prostitutes kept many areas off limits to much of the honest and industrious citizenry [12]. Even for the 90% of Americans who lived in small villages and in the countryside, life, as Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) had long since observed, was often “solitary, nasty, brutish, and short.”

In the trans-Appalachian West and South, things were even worse. Along with the notion that every man could govern came the idea that every man—high or low, mighty or middling—could be a self-appointed judge and jury. Gouging, brawling, and brandishing everything from swords to shillelaghs was commonplace in taverns, inns, and way stations across the restless nation. To refine the process, prominent Southerners replaced eye gouging, clubs, and knives with a more systematized approach of shooting each other at point-blank range, all with similar results. Upon no mere whim, South Carolina's governor, John Lyde Wilson (1784–1849), wrote The Code of Honor; or, Rules for the Government of Principals and Seconds in Duelling in 1838, long after most states had outlawed the practice [13]. The pattern of violence was not restricted to the traditional South. In Kentucky, the commonwealth eschewed its border-state status for following the Southern example of murder and mayhem. Robert Ireland has shown that early nineteenth-century Kentucky, for example, was indeed a “dark and bloody ground” with a consistently high homicide rate, often exceeding the most murderous urban areas of the modern United States many times over and yet well in keeping with the statistically high rates of most Southern states of the period [14]. For more “refined” Kentuckians, dueling was an all-too-preferred method of conflict resolution. The chronicle of dueling contests that sent many a Kentuckian to an early grave is long, extending beyond the Civil War [15].

Homicide notwithstanding, the Jacksonian era could often be riotous. Twenty incidents of rioting happened between 1828 and 1833 [16]. Some sixteen riots broke out in 1834 alone; one year later the number rose to thirty-seven, leaving sixty-one dead; by 1840, there were 125 killed in mob violence [17]. The causes were various—ethnic hatred, xenophobia, class tensions, zealous friends and foes of slavery, and so on. But, as historian David Grimstead has pointed out, “For the Jacksonian period, the diversity of type and circumstance of riot offers presumptive evidence that social violence owed less to local and particular grievances than to widely held assumptions and attitudes about the relation of the individual to social control” [18]. Those assumptions were virtually anthropomorphized in Jackson himself and gave a new psychological context to democratic ideals. Although Jackson himself was quick to denounce the rioting, he had unwittingly served as the symbolic catalyst for it. Grimstead argued,

[H]is lack of formal education, his intuitive strength, his belief that anyone had the ability to handle government jobs, his transformation of the presidency from that of guide for the people to a personalized representative of Democracy, all helped create a sense of power justly residing in the hands of each man rather than in the state and a sense of the need for democratic citizens to pursue the right comparatively free from mere procedural trammels and from deference to their social and intellectual betters. [19]

Out of such notions also came a pervasive anti-intellectualism that belittled both learning and the learned [20]. Yet Jacksonian America was infused with a more complex, richer dynamic. A deeper look under the rugged and unsightly exterior of social unrest, ignorance, and violence reveals a more sophisticated, urbane society.

LITERACY IN JACKSONIAN AMERICA

It would hardly be news to any observer past or present that the kind of aberrant behavior described above was most prevalent among the least educated elements of society. Smith's disgust at the people's inaugural suggested that with the advent of their Western hero, Jackson, the flood gates were opened as the great sea of unwashed and unlettered masses both literally and figuratively poured into the seat of government. But how unlettered really were the masses described by this horrified onlooker?

The question immediately raises some difficult problems. First, the U.S. Census did not even tabulate literacy rates until 1840. Second, the methodologies employed in that census were both crude and unreliable [21]. Kenneth A. Lockridge has provided a tenable model of analysis in his investigation of literacy in colonial America [22]. Applying the methods of earlier researchers in Europe, Lockridge examined signatures on wills and the extent of books and other reading material listed in probate records to conclude that fervent Protestantism, especially Puritan ideology, and the resulting push for school laws made New England preeminently literate [23]. Moreover, colonial literacy rates examined outside New England show that the colonies compared quite favorably with England.**

But it would be wrong to conclude that the United States emerged from the war for independence wholly literate. In 1800, a quarter of the citizenry of the new republic in the north could neither read nor write and in parts of the south the number was as high as half [25]. By 1840, U.S. Census data suggested that the number had shrunk to a remarkably low 9% [26, 27]. “Evangelical Protestant morality, a fervent nationalism, and an ethic of capitalism which recognized the value of a literate public,” argued Lee Soltow and Edward Stevens, “had made literacy a high-priority social cause” [28]. As virtues associated with progress, reading and writing were most vigorously promoted in common school reforms started in the early part of the nineteenth century, until by 1840 something resembling an “ideology of literacy” had been established [29].

Still, the nature of that literacy remains in question. These data are impressionistic. Lockridge's signature rates tell us little about functional literacy, the mere ability to scrawl one's name on a will or other legal document does not accord with a meaningful concept of literacy. Likewise, Soltow and Stevens relied heavily upon the 1840 census, which merely took the respondent's word for it about their ability to read or write. The opportunities for the inflation of literacy rates in this method are many, and here too the mere ability to read or write indicates little about the nature and extent of those abilities. Indeed, one analyst has suggested that whatever the overall percentages might have been, functional literacy through the middle half of the nineteenth century was rather low in North America. According to Harvey J. Graff, “popular qualitative levels of literacy were not impressively high and . . . there was a significant disparity between literacy viewed quantitatively and qualitatively” [30]. “Popular levels of literacy,” asserted Graff, “were sufficient for many of the daily and ordinary demands placed upon them” but wholly “insufficient for ‘higher’ demands,” including intellectual life [31].

This conclusion needs careful examination. The indices of functional literacy are at least suggested in evidence beyond estate records and specific literacy statistics. The establishment of institutions supporting literate culture in Antebellum America infers at least some measure of functional literacy. The 1840 census, for example, revealed nearly 50,000 primary and common schools, more than 3,200 academies and grammar schools, and 171 colleges and universities. That same census also indicated the existence of 1,540 printing offices and nearly 1,400 newspapers in the United States [32]. Besides the expansion of schools and print media, libraries were also proliferating, from a mere 413 in 1800 to a record 3,031 by 1855 [33].†† Historians have long investigated the development of high culture in the United States in the early nineteenth century and have unequivocally demonstrated that the period was not only comparatively active in this regard but indeed surprisingly advanced precisely where one would not expect it to be, the frontier [34–39]. This is not to suggest that the United States in the early nineteenth century rivaled the great cultural centers of London and Paris, but neither was it the crude, bucolic republic as is often assumed.

Of course all this may beg the question. Libraries may abound, frequented by only a few; literary societies may be founded in the most out-of-the-way places, their meetings attended by only the founders; athenaeums may exist more on paper than in fact; schools may be started, all of which offer inadequate curricula and poor instruction. In short, the mere presence of high-culture institutions does not prove widespread functional literacy.

The problem of accurately assessing the impact of literate culture in this period is compounded by the contemporaneous veneration of the “common man” as a natural font of wisdom free from the corrupting influences of elitist institutions, the leitmotif of an era that hailed this as a democratic virtue. Yet the American republic was also built upon foundations rooted in the Enlightenment and rational Protestantism, giving the age social and political paradigms that were inherently contradictory. In this context, the dramatic rise of literacy during the Jacksonian era becomes a dichotomy of continental proportions. Graff has explained the literacy rate as representing simple rather than functional proficiencies, but the question of the quality behind the numbers remains unanswered. One solution may at least be suggested in a movement full of its own contradictions—the Thomsonians.

THE THOMSONIAN SYSTEM

Folk healing and domestic medicine in America dates from the earliest colonial settlements, and herbalism in its broadest sense can be found in pre-Columbian cultures, but, until Samuel Thomson started his own peculiar brand of botanicism, nothing resembled an organized movement. Thomson believed that orthodox, university-trained physicians were killing their patients with toxic minerals like tartar emetic (antimony) and calomel (mercurous chloride). Convinced that he had discovered the source of health and healing in nature's apothecary, he developed a system of herbal remedies, the rights to which could be purchased. As early as 1806, Thomson tested his system on victims of yellow fever in Boston and New York City, and, during this period, his regimens were accorded the title “Thomsonian” [40]. Thomson traveled widely spreading his herbal gospel. He usually announced his arrival in city, town, or hamlet by issuing invitational fliers to a public lecture, whereupon he explained his system of medicine, offered family rights to practice it for $20, and then proceeded to demonstrate it to purchasers by example, usually on one of the rights holders. To give his system some cohesion and unity, Thomson then encouraged the establishment of Friendly Botanic Societies, where rights holders could join together in fellowship. These societies were important, because they formed a necessary network through which designated agents could be appointed to spread the Thomsonian system even farther.

Thomson prided himself on creating a health care system that virtually anyone could follow. With the numbering of remedies one through six (number one, so-called “Indian tobacco” or Lobelia inflata being his favorite), all that was required of the family practitioner was an ability to recall the instructions (Thomson devised little memory verses to facilitate this) and to count to six. Thus, Thomson's devoted followers could apply his remedies “without knowing a single letter of the alphabet” [41].

By 1813, Thomson had obtained a patent for a remedy that Dr. William Thornton of the U.S. Patent Office termed a “Fever Medicine” [42]. The duly authorized patent was both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, it gave Thomson some legal protection and remedy against those who deigned to usurp his system for their own, on the other hand, it became so jealously guarded by Thomson that it more often than not served merely as a source of contention and division within his growing circle of followers, divisions that turned friends into foes. Thomson quickly came to regard many agents not as allies but as enemies. He became convinced that duplicitous agents sailing under the Thomsonian banner were making unnecessary “improvements” to his system, were out to steal the profits for themselves, or were selling inferior, bootlegged products for quick profit. Thomson's fears were both real and imagined, but he tried to give added protection to his patent as well as create a vehicle for its expansion with the publication of his New Guide to Health, or Botanic Family Physician in 1822 [43]. But even this became a source of difficulty as pirated editions began to dot the countryside.

Eventually, Thomson spent most of his time railing against various “impositions” and “counterfeits” foisted upon his system. Adamantly opposed to the creation of Thomsonian schools of medicine that might have given some essential stability to his loose confederacy of botanics and increasingly paranoid and accusatory, the botanic leader had by the late 1830s become insufferable. Former proteges like Alva Curtis (1797–1881) eventually broke away in disgust and established rival botanical groups, the physio-medicals being the most noteworthy [44].

By the time of Thomson's death in September of 1843, botanicism had started to head in new directions. As mentioned, Curtis was launching the physio-medicals but also the former Beachites (followers of Wooster Beach [1794–1868]) had found success as “eclectics” under Beach's able apostle, Thomas Vaughan Morrow (1804–1850) [45]. When the Eclectic Medical Institute was chartered in Cincinnati, Ohio, just two years after Thomson's death, popular botanicism had clearly outgrown its rough-hewn beginnings to find renewed vigor in more “respectable” and professional schools of practice [46]. But the Thomsonian movement's meteoric rise and rather inglorious end belies its significance as a phenomenon that both reflects and reveals much about the time in which it resided.

THOMSONIANS AS JACKSONIANS

The Thomsonian system of botanical healing located itself firmly within Jacksonian egalitarianism. The zeitgeist of the age described earlier—with its preference for experience over theory, instinctive genius over acquired knowledge, and equality of commoners over elitist rank and privilege—formed the essential foundation for its promotion and expansion. “Only in understanding this spirit,” wrote Thomson's biographer John S. Haller, “can one appreciate the loyalty that so many Americans extended to Dr. Samuel Thomson, his many agents, and their courses of medicine” [47].

Thomson utilized a populist rhetoric that made his system of medicine appear particularly suited to the requirements of a new democratic experiment. He viciously attacked the “learned Doctors of Medicine” for their credentialed pretensions and their elitism. Referring to the regular medical profession, Thomson complained,

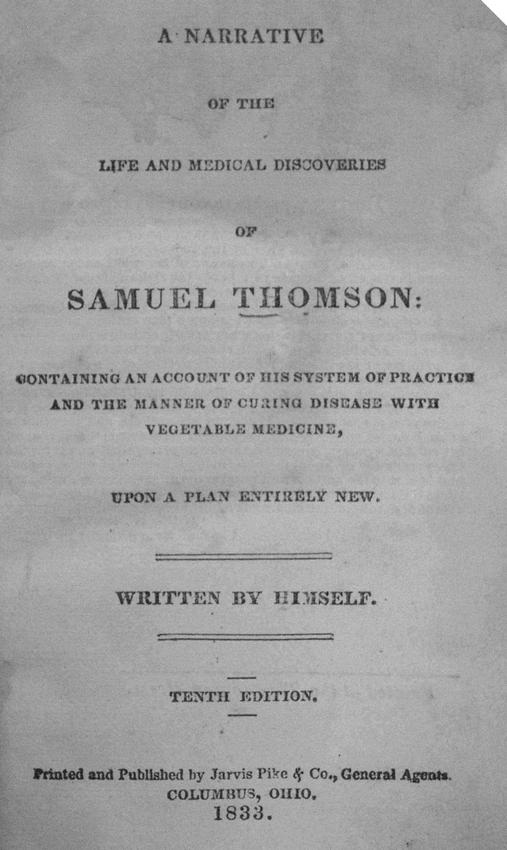

From those who measure a man's understanding and ability to be beneficial to his fellow men only from the acquisition he has made in literature from books; from such as are governed by outward appearance, and who will not stoop to examine a system on the ground of its intrinsic merit, I expect not encouragement but opposition. [48] (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

A New Guide to Health, or Botanic Family Physician

Instead of being hoodwinked by a recondite science cloaked in the “dead language” of Latin, Thomson beckoned commoners to embrace his simple and natural regimens. “A man can be great without the advantages of an education,” he declared, “but learning can never make a wise man of a fool; the practice of physic requires a knowledge that cannot be got by reading books; it must be obtained by actual observation and experience” [49]. Thomson's relationship to the regular, mainstream medical profession was expectedly strained. Early on, Thomson courted favor with some of his generation's most eminent practitioners like Benjamin Rush (1746–1813) and Benjamin Smith Barton (1766–1815), both of whom died before rendering verdicts on his medicines. While the prominent regular Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse (1754–1846) became a vocal supporter of Thomsonian medicine, most did not. Famed Ohio Valley scholar and physician Daniel Drake (1785–1852) spoke for the majority of his colleagues in denouncing it as “planted in the ignorance of the multitude” [50].

This animosity worked to Thomson's advantage, because it clearly separated him from a profession that had already lost caste among the people. Although all physicians utilized an extensive botanical materia medica, their heroic bleeding, purging, and puking made recipients wary of their “care.” Added to this was an attitude among regular physicians that struck many as supercilious and condescending. The faith of Thomson that all people could be their own physicians was juxtaposed to most regular physicians who thought little of their patients' abilities to appreciate even the most rudimentary aspects of the healing art. If Drake's denunciation of the “ignorant multitude” was not enough, there was New York physician David Meredith Reese (1800–1861), who felt that the citizens of his city were under a “reign of humbug” and that “thousands more will be prepared for still farther [sic] experiments in gullibility, ad infinitum” [51]. Similarly, New England blueblood and revered physician, Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809–1894) believed that the general public was “hopelessly ignorant” regarding medicine and that most demonstrated a perfect record of “incompetence to form opinions on medical subjects” [52]. Whether the great Rush would have lent his prestige to Thomson's system is not known, but its blatantly entrepreneurial aspects would undoubtedly not have impressed U.S. medicine's leading light. The physician-patriot was appalled by the new spirit of capitalism pervading his beloved Philadelphia, making him “sometimes wish I could erase my name from the Declaration of Independence” in what he termed this “bedollared nation” [53].

In this context of professional distrust and elitism, Thomson tried hard to portray himself as a friend and champion of the people. It worked. In 1834, Thomsonians claimed one and a half million adherents [54]; by the 1840s, optimistic estimates placed their number at between four and six million [55]. “The people,” declared The Thomsonian Recorder, “the common people, have been found capable of examining, judging, and deciding correctly. Give them the facts, the whole facts, and nothing but the facts. By them, we conquer!” [56]. But this statement represents more than popular hyperbolic boilerplate; within it resides a significant question: How did the Thomsonians distribute their facts? More than a loose network of itinerate peddler-agents, the Thomsonian movement was promulgated and supported through a complex infrastructure of pamphlets, books, and journals aimed at an implicitly literate audience.

THOMSONIAN LITERATURE AND LITERACY

For all of Thomson's distrust of formal education and the intelligentsia of his day, undoubtedly much of this was a marketing ploy to give his system of medicine a broad popular appeal. As the gospel spread and found adherents, Thomson abandoned his admonitions against book learning and wrote his own book in an attempt to keep his principles pure and his dogma at close reach of every practitioner and agent. Beyond his New Guide to Health an extensive journal literature soon attached itself to the growing movement, some efforts authorized by the founder, some not. Haller is quite correct in characterizing the Thomsonian leadership as “well educated, and their journals well written and well read” [57].

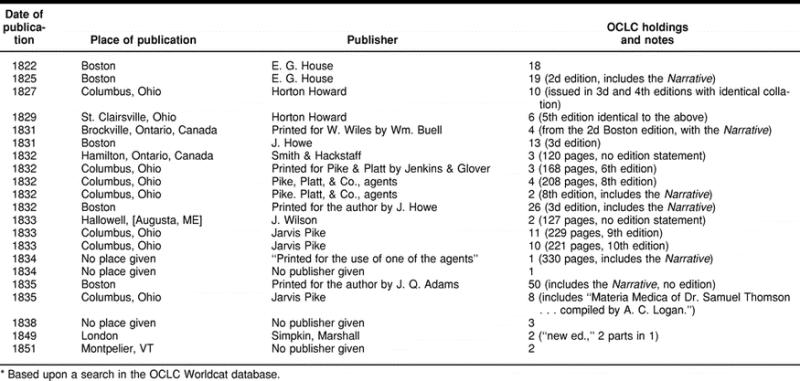

If Thomson's New Guide to Health had run into only one or two editions of short print runs and local distribution, it would be easy to discount his major literary effort as little more than a zealot's ephemera. But copies appeared virtually everywhere in North America in both legitimate and bootlegged editions, with the New Guide to Health eventually finding a publisher in England. Detailed analysis of extant library holdings indicated at least fourteen different publishers in twenty-one different editions from 1822 to 1851, issued from the United States, Canada, and Great Britain (Table 1). Furthermore, although individual editions can be quite scarce, nearly 180 years later, copies of the New Guide to Health abound, with nearly 200 institutional holdings of at least one copy of the book and perhaps hundreds more in private hands.‡‡ This suggests that the New Guide to Health was widely distributed and widely sold throughout the period. If Thomson prided himself on creating a course of therapy that any illiterate could follow, obviously many were reading at some length about the system they had adopted. Moreover they were reading at fairly sophisticated levels, for Thomson's New Guide to Health was no child's primer; it clearly required a fairly advanced degree of reading ability and comprehension to digest its contents.

Table 1 A bibliographical analysis of Samuel Thomson's New Guide to Health, or Botanic Family Physician*

Thomson was not the only one penning laudatory accounts of this health system for commoners. Samuel Robinson delivered a series of lectures in Cincinnati, apparently unsolicited by and without the knowledge of Thomson. Subsequently published in Columbus, Ohio, by Horton Howard in 1829 and one year later in Boston by J. Howe [58], Thomson's champion demonstrated an almost schizophrenic love-hate relationship with intellectualism so typical of the times in which he lectured. Robinson attacked “the wise and learned” for their “strong prejudice and opposition” to Thomson, whom he characterized as an illiterate plough-boy who had devised a superior theory of medicine based upon experience, easily explained and submitted to the people [59]. Despite his praise of Thomson's “illiteracy,” he went on to invoke virtually every learned figure in Western civilization in support of this people's medicine. To follow Robinson's argument—even orally presented—requires a broad knowledge of history and at least a nodding acquaintance with the luminaries of the Western world.

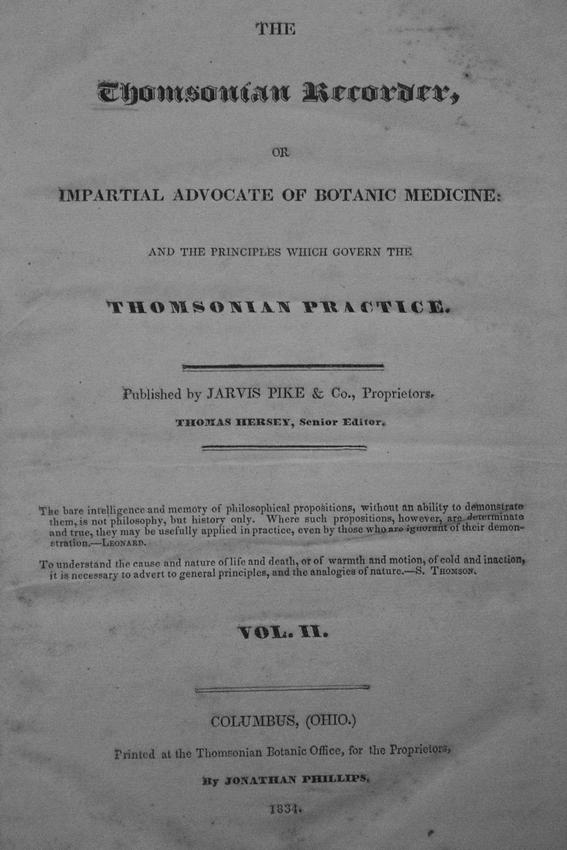

More important than the Robinson lectures, however, was the wide diffusion of Thomsonian journal literature in all sections of the country (Figure 3). Haller has listed and described some eighty-six different journal titles from 1822 to 1860, most issued monthly or semimonthly [60]. The first and perhaps most important of these was The Thomsonian Recorder, edited by former regular physician and early Ohio resident, Thomas Hersey (1766–1836). Hersey eventually became disgusted with the internecine fighting among the botanics, and Alva Curtis assumed editorial duties in 1836 shortly before his death, but, from the biweekly's inception in 1832 through its early years, Hersey served as the journalistic mouthpiece of Thomsonian medicine. By all accounts, this publication was well received. Just two years after its first issue, Hersey was distributing more than 2,000 copies to “the disciples of Dr. Samuel Thomson scattered throughout every State and almost every Territory in this Republic” [61].

Figure 3.

The Thomsonian Recorder

If a glimpse of a more deeply intellectual strain in the Thomsonian movement is revealed in Robinson, an even clearer view is afforded with Hersey. The usual egalitarian rhetoric was still there in profusion, but occasionally The Recorder's senior editor would put aside the procrustean populism and speak to the importance of universal education as the foundation of an informed public. Insisting it was the only way to lead the public to informed choices about their own welfare (including and especially their health care), Hersey welcomed an enlightened democratic spirit that was rooting out all forms of prejudice and superstition. At length, he declared:

Among the vast proportion of the people of our own country, where the laborious multitude are more generally endowed with what is proverbially called a common education, and to a better effect than any other people of the same grade on earth, yet much remains to be done. . . .

Our own bodies are fearfully and wonderfully made, and each contain a world in miniature. Particularly in regard to a sickly or healthy state of the human system, we would say, it is an object worthy of special attention.

The world is now better prepared than formerly to enter extensively into these inquiries. About the middle of the eighteenth century the labors of the press increased, books were multiplied, and numerous new facilities for the acquisition of useful knowledge opened up a thousand avenues to the temple of science, that were sadly obstructed before.

Our patriot sires had been peculiarly careful, particularly in the new Eastern States, to instruct their children in their maternal tongue and the rudiments of useful knowledge. With a view to the accomplishment of these important objects, we find at an early period in the history of our country, not only colleges and academies were instituted and liberally sustained, but common schools were instituted at all convenient points, and competent teachers provided. . . .

Men have begun to feel the dignity of human nature, to assert their civil and religious rights and privileges, which the iron arm of despotic power had wrested from them. The spirit of inquiry is abroad in the earth. A light has risen in the civilized world that will not be extinguished until its benign influence shall gladden the hearts of nameless millions where the day of science has never dawned. [62]

Hersey all but linked the Thomsonian movement to the efforts at providing a universal education to citizens of the new republic. In so doing, he probably gave a more accurate depiction of the symbiotic relationship that existed between a literate public and self-help medical care of the brand that Thomson promoted.

Clearly, the proliferation and broad diffusion of Thomsonian literature provided cohesion to a group that might otherwise have simply fallen apart in the chaos of mass consumption. The fact that a distinctly Thomsonian brand of botanicism could survive in any kind of tangible, definable form was unquestionably the result of the literary structures that surrounded it. Thomson could extol the virtues of illiteracy but it was among the reading public that his ideas were refined, delineated from other popular health systems, and carried forward. While counting to six might have been the only requirement to practice Thomsonian medicine, the many editions of the New Guide to Health and the many more journals that arose as a result of it bespeak a broad and literate consumer base that ran contrary to its promotional rhetoric.

There was perhaps a final irony to the Thomsonian movement. Although Thomson himself attacked organized religion and vilified its clergy, all of whom he viewed as pretentious hypocrites, his system was built upon the model of evangelical Protestantism, and Thomsonian medicine had an unmistakable religious connotation to it, even to the point of Thomsonian prayers [63]. With his Friendly Botanical Societies, he had created an effective organizational structure not unlike denominational churches; with his agents, he was able to appoint proselytizers the equal of any fervent missionary; with his New Guide to Health, he had established a concrete creed and catechism that his flock could follow. But Thomson had neither the charisma of a Christ nor the power of a pope, and he soon found himself riddled with apostates and mired in sectarian conflict, which ultimately spelled the demise of his grassroots movement as he had conceived it.

CONCLUSION

Understood in this context, Thomsonism can be seen as an heir to, if not an outright catalyst for, literacy. Like Puritanism, which became an important force in creating a literate laity in colonial New England [64], the Thomsonian movement (especially in its latter phases) was largely exposited and promoted through a fairly extensive literary network of pamphlets, books, broadsides, and journals. Thus, support for a common school movement (the chief source of the dramatic rise in literacy rates between 1800 and mid-century) could have unlikely allies in the Thomsonians who, their rhetorical effusions notwithstanding, at least in part relied upon a literate public. Furthermore, the literature of this widely dispersed and popularly based self-help medical movement represents substantial prima facie evidence that literacy rates for this period went well beyond simple levels. Claims that the statistically high literacy rate for the period chiefly represent nonfunctional skill levels need to be reevaluated in light of this evidence.

Upon more careful examination, associating Thomsonism with a rising ideology of literacy is not surprising. Thomson's system was much more proactive than conventional health care where patients passively submitted to diagnosis and treatment by a credentialed medical authority. Although Thomson's adherents followed the instructions of their master, they became at the same time active participants in their own care: they chose to use his numbered remedies; they interpreted their symptoms, matched them to the proper number, began treatment, and then monitored the results. They could remain collaboratively engaged with issues of their own health and healing through the Friendly Botanic Societies. This kind of self-help medicine resonated well with the rise of mechanisms for self-education and efforts at social uplift not only through schools but also through a lyceum and public library movement that expanded throughout Antebellum America [65, 66].§§

Although Thomson's grassroots medicine coincided well with the educational ethos of the period, the early botanical medical movement has been shown to mirror the internal contradictions of the Jacksonian era itself, making the role of Thomsonism in literacy easily missed. Its many proclamations of a wise and unlettered yeomanry ready to take charge of its own health care concealed a more lasting effort to rely upon a literate public able to receive, define, and promote its tenets, just as the veneration of a natural egalitarianism free from all corrupting influences belied a growing ideology of literacy to meet the needs of evangelical Protestantism, nationalism, and expanding capitalism. In the end, the botanical movement could not survive on populist rhetoric alone and sought survival in scientific respectability through schools and professionalization [69]. Likewise, the age that ostensibly repudiated education and culture in a free and unfettered democracy was also the age that promoted progress and all the accoutrements associated with it—schools, churches, libraries, and assorted improvement societies. “Jacksonian democratic thought, built upon a philosophy of nature in the concrete,” concluded John William Ward, “was oriented toward a period in American social development that was slipping away at the very moment of its formulation” [70]. So too was the Thomsonian movement.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks John S. Haller, Jr., Ph.D., professor of history at Southern Illinois University, for reading this essay in manuscript and for his book, The People's Doctors, that inspired it.

Footnotes

* This paper was awarded the 2002 Murray Gottlieb Prize by the Medical Library Association.

† Some historians might quibble over utilizing a source now nearly fifty years old as an analytical framework for the present study, but Ward's “myth and symbol” approach made a contribution that was important and enduring. More recent historians of the period still reference his Andrew Jackson: Symbol for an Age as providing valuable insights into their own work [2, 3], and historiographers continue to cite Ward as among the most important Myth and Symbol writers [4, 5]. Historian Linda K. Kerber cautions her colleagues against dismissing the Myth and Symbol school as passé. We are, she insists, “deeply indebted to it” for the quality of its prose and for broadening the definition of “art” as an area of legitimate academic inquiry [6]. Myth and Symbol writers like Ward taught that popular texts formerly deemed too “common” and “lowbrow” for serious study were, in fact, rich resources of social and intellectual history.

‡ For purposes of this study, “functional” literacy is defined as reading and writing skills “sufficiently advanced to enable the individual to participate fully and efficiently in activities commonly occurring in his [or her] life situation that require a reasonable capability of communicating by written language,” as opposed to “simple” literacy, which is the ability to sign one's name and read a simple message [7].

§ Nepotism and the other attendant evils of the spoils system were not addressed until the passage of civil service reform with the Pendleton Act (1883).

** For the generation born around 1700, the colonial signature rates in Pennsylvania and Virginia were about 60% compared to an overall 50% among the adult population of England. In New England, the signature rate was nearly 85% [24].

†† Haynes McMullen points out that the actual ratio of libraries to population declined somewhat for the period, but ratios by definition compare the distribution of only two variables. Given the expanding nature of the population over an increasingly vast area, a third variable (i.e., geographic distribution of libraries) should also be considered. There is reason to believe that in this regard library development was quite favorable (see note §§). With the available data as presented by McMullen, the more meaningful number remains the sheer number of libraries established.

‡‡ A search in three major antiquarian dealer Websites—http://www.bookfinder.com, http://www.abebooks.com, and http://www.ablibris.com—found the book available in several different editions.

§§ It is interesting to note that both the Midwest (a Thomsonian stronghold) and the far West showed a consistently high ratio of libraries to population [67]. A tremendous spike in the growth of libraries occurred in 1855 to more than 3,000 with the establishment of a network of township libraries in Indiana [68].

REFERENCES

- Ward JW. Andrew Jackson: symbol for an age. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Levine LW. Highbrow/lowbrow: the emergence of cultural hierarchy in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988:240. [Google Scholar]

- Allen M. Western rivermen, 1763–1861: Ohio and Mississippi boatmen and the myth of the alligator horse. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University, 1990:2. [Google Scholar]

- Kerber LK. Diversity and the transformation of American studies. Am Quart. 1989 Sep; 41(3):415–31. [Google Scholar]

- Higham J. The future of American history. J Am Hist. 1994 Mar; 80(4):1297; 1289–309. [Google Scholar]

- Kerber LK. Diversity and the transformation of American studies. Am Quart. 1989 Sep; 41(3):415–31. [Google Scholar]

- Technical Notes on the 1994 Functional Literacy, Education and Mass Media Survey (FLEMMS). . [Web document]. Social and Demographic Statistics Division, National Statistics Office. [cited 14 Jun 2002]. <http://www.census.gov.ph/data/technotes/noteflemms94.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Remini RV. Quoted in: . The life of Andrew Jackson. New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1990:181. [Google Scholar]

- Smith [MB]. The inauguration of Andrew Jackson. In: The annals of America: steps toward equalitarianism. v. 5. Chicago, IL: Encyclopedia Britannica, 1976:290. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald F. Quoted in: . The American presidency: an intellectual history. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1994:317. [Google Scholar]

- Morison SE. The Oxford history of the American people. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1965:422–6. [Google Scholar]

- Larkin J. The reshaping of everyday life, 1790–1840. New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1988:281–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JL. The code of honor; or, rules for the government of principals and seconds in duelling. Charleston, SC: T. J. Eccles, 1838. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland RM. Homicide in nineteenth century Kentucky. The Register of the Ky Hist Soc. 1983 Spring; 81(2):134–53. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JW. Famous Kentucky duels. Lexington, KY: Henry Clay Press, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Grimstead D. Rioting in its Jacksonian setting. The Am Hist Rev. 1972 Apr; 77(2):362; 361–97. [Google Scholar]

- Grimstead D. Rioting in its Jacksonian setting. The Am Hist Rev. 1972 Apr; 77(2):362; 361–97. [Google Scholar]

- Grimstead D. Rioting in its Jacksonian setting. The Am Hist Rev. 1972 Apr; 77(2):362; 361–97. [Google Scholar]

- Grimstead D. Rioting in its Jacksonian setting. The Am Hist Rev. 1972 Apr; 77(2):362; 361–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ward JW. Andrew Jackson: symbol for an age. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Kaestle CF, Damon-Moore H, Stedman LC, Tinsley K, and Trollinger WV. Literacy in the United States: readers and reading since 1880. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991:24. [Google Scholar]

- Lockridge KA. Literacy in colonial New England: an enquiry into the social context of literacy in the early modern West. New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Lockridge KA. Literacy in colonial New England: an enquiry into the social context of literacy in the early modern West. New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Lockridge KA. Literacy in colonial New England: an enquiry into the social context of literacy in the early modern West. New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 1974:88. [Google Scholar]

- Soltow L, Stevens E. The rise of literacy and the common school in the United States: a socioeconomic analysis to 1870. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1981:153. [Google Scholar]

- Soltow L, Stevens E. The rise of literacy and the common school in the United States: a socioeconomic analysis to 1870. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1981:155. [Google Scholar]

- Graff HJ. The legacies of literacy: continuities and contradictions in western culture and society. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1987:342–3. [Google Scholar]

- Soltow L, Stevens E. The rise of literacy and the common school in the United States: a socioeconomic analysis to 1870. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1981:153. [Google Scholar]

- Soltow L, Stevens E. The rise of literacy and the common school in the United States: a socioeconomic analysis to 1870. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1981:149. [Google Scholar]

- Graff HJ. The labyrinths of literacy: reflections on literacy past and present. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995:73. [Google Scholar]

- Graff HJ. The labyrinths of literacy: reflections on literacy past and present. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995:73. [Google Scholar]

- United States historical census data. . [Web document]. Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR). [rev. 24 Mar 1998; cited 14 Jun 2002]. <http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/census/>. [Google Scholar]

- McMullen H. American libraries before 1876. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000:48:table 3.3. [Google Scholar]

- Miller JM. The genesis of Western culture: the upper Ohio Valley, 1800–1825. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Peckham HH.. Books and reading on the Ohio Valley frontier. The Mississippi Valley Hist Rev. 1958;44(4):649–63. [Google Scholar]

- Harris MH. Books on the frontier: the extent and nature of book ownership in southern Indiana, 1800–1850. Libr Q. 1972 Oct; 42(4):416–29. [Google Scholar]

- Winterich JT. Early American books & printing. Reprinted. New York, NY: Dover, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wade RC. The urban frontier: pioneer life in early Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Lexington, Louisville, and St. Louis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery MA. The significance of the frontier thesis in Kentucky culture: a study in historical practice and perception. Register Ky Hist Soc. 1994 Summer; 92(3):239–66. [Google Scholar]

- Haller JS. The people's doctors: Samuel Thomson and the American botanical movement, 1790–1860. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000:31–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller JS. The people's doctors: Samuel Thomson and the American botanical movement, 1790–1860. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000:31–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller JS. The people's doctors: Samuel Thomson and the American botanical movement, 1790–1860. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000:31–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson S. New guide to health, or botanic family physician. Boston, MA: E. G. House, 1822. [Google Scholar]

- Haller JS. Kindly medicine: physio-medicalism in America, 1836–1911. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery MA. Thomas Vaughan Morrow, 1804–1850: the apostle of eclecticism. Trans Ky Acad Sci. 1996 Summer; 57(2):113–9. [Google Scholar]

- Haller JS. Medical protestants: the eclectics in American medicine, 1825–1939. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Haller JS. The people's doctors: Samuel Thomson and the American botanical movement, 1790–1860. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000:31–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson S. A new guide to health, or botanic family physician. Boston, MA: J. Q. Adams, 1835:7. (This and all subsequent references are to this edition.). [Google Scholar]

- Samuel T. A narrative of the life and medical discoveries of the author. Boston, MA: J. Q. Adams, 1835:9. (Bound with: A new guide to health.). [Google Scholar]

- Drake D. The people's doctors: a review by “the people's friend.”. Cincinnati, OH, 1829:8. [Google Scholar]

- Reese DM. Humbugs of New-York: being a remonstrance against popular delusion; whether in science, philosophy, or religion. New York, NY: John S. Taylor, 1838:21–2. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes OW. The young practitioner. In: Medical essays 1842–1882. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1883:379. [Google Scholar]

- Rush B. Letter to: John Adams. Philadelphia, PA, 13 June 1808. In: Butterfield LH, ed. The Letters of Benjamin Rush. v. 2. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press for The American Philosophical Society, 1951:965–7. [Google Scholar]

- [Hersey T]. Progress of botanic medicine. The Thomsonian recorder. 1834 Mar 1; 2(11):169. [Google Scholar]

- Haller JS. The people's doctors: Samuel Thomson and the American botanical movement, 1790–1860. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000:184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [Hersey T]. The Thomsonian recorder. 1834 Feb 15; 2(10):133. [Google Scholar]

- Haller JS. The people's doctors: Samuel Thomson and the American botanical movement, 1790–1860. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000:251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S. A course of fifteen lectures on medical botany, denominated Thomson's new theory of medical practice. Boston, MA: Jonathon Howe, 1830. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S. A course of fifteen lectures on medical botany, denominated Thomson's new theory of medical practice. Boston, MA: Jonathon Howe, 1830:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Haller JS. The people's doctors: Samuel Thomson and the American botanical movement, 1790–1860. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000:271–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [Hersey T]. The Thomsonian Recorder. 1834 Feb 1; 2(9):132. [Google Scholar]

- Hersey T. A lecture. The Thomsonian Recorder. 1834 Mar 29; 2(13):194. [Google Scholar]

- Haller JS. The people's doctors: Samuel Thomson and the American botanical movement, 1790–1860. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000:81–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockridge KA. Literacy in colonial New England: an enquiry into the social context of literacy in the early modern West. New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 1974:97–9. [Google Scholar]

- McMullen H. American libraries before 1876. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000:33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shera JH. Causal factors in public library development. In: Harris MH, comp. Reader in American library history. Washington, DC: NCR Microcard Editions, 1971:141–62. [Google Scholar]

- McMullen H. American libraries before 1876. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000:42:table 3.1. [Google Scholar]

- McMullen H. American libraries before 1876. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000:34. [Google Scholar]

- Berman A, Flannery MA. America's botanico-medical movements: vox populi. New York, NY: Pharmaceutical Products Press, 2001:19,101–47 passim. [Google Scholar]

- Ward JW. Andrew Jackson: symbol for an age. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1955:45. [Google Scholar]