Abstract

Aerolysin of the Gram-negative bacterium Aeromonas hydrophila consists of small (SL) and large (LL) lobes. The α-toxin of Gram-positive Clostridium septicum has a single lobe homologous to LL. These toxins bind to glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins and generate pores in the cell’s plasma membrane. We isolated CHO cells resistant to aerolysin, with the aim of obtaining GPI biosynthesis mutants. One mutant unexpectedly expressed GPI-anchored proteins, but nevertheless bound aerolysin poorly and was 10-fold less sensitive than wild-type cells. A cDNA of N-acetylglucosamine transferase I (GnTI) restored the binding of aerolysin to this mutant. Therefore, N-glycan is involved in the binding. Removal of mannoses by α-mannosidase II was important for the binding of aerolysin. In contrast, the α-toxin killed GnTI-deficient and wild-type CHO cells equally, indicating that its binding to GPI-anchored proteins is independent of N-glycan. Because SL bound to wild-type but not to GnTI-deficient cells, and because a hybrid toxin consisting of SL and the α-toxin killed wild-type cells 10-fold more efficiently than GnTI- deficient cells, SL with its binding site for N-glycan contributes to the high binding affinity of aerolysin.

Keywords: N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I/aerolysin/N-glycan/glycosylphosphatidylinositol/toxin

Introduction

A wide variety of mammalian proteins are anchored to the cell surface via glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) (McConville and Ferguson, 1993; Kinoshita et al., 1995). GPI biosynthesis is essential for embryogenesis and proper skin development in mice, as demonstrated by gene targeting (Tarutani et al., 1997). A deficiency of GPI causes paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, indicating a critical role for the GPI anchoring of proteins in the regulation of the complement system (Takeda et al., 1993). In contrast, GPI is not essential for growth of mammalian cells and many mutant cell lines defective in GPI biosynthesis have been established. Twenty genes involved in the biosynthetic pathway of GPI have been identified, mainly by means of complementation cloning using mutant cells (Kinoshita and Inoue, 2000). New mutants are required for cloning as yet missing genes and for reconstituting the pathway for full characterization of GPI biosynthesis.

In addition to these physiological roles, GPI-anchored proteins act as receptors for bacterial cytolytic toxins, namely aerolysin (Diep et al., 1998b) and clostridial α-toxin (Gordon et al., 1999). The plant cytolytic toxin enterolobin (Fontes et al., 1997) may also bind to GPI-anchored proteins. Mutant cell lines defective in GPI biosynthesis (Nelson et al., 1997; Gordon et al., 1999) and affected cells from patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (Brodsky et al., 1999) are resistant to aerolysin.

Aerolysin is the major virulence factor of the Gram-negative bacterium Aeromonas hydrophila, which causes gastroenteritis, deep wound infection and septicemia (Buckley, 1999). Aerolysin, secreted as a soluble inactive protoxin termed proaerolysin, binds to GPI-anchored proteins, such as Thy-1 (Nelson et al., 1997), contactin (Diep et al., 1998b) and erythrocyte aerolysin receptor (Cowell et al., 1997). A C-terminal peptide is then cleaved off by cell surface proteases, such as furin, and the toxin thus activated forms heptameric, insertion-competent channels, which in turn insert into the membrane and kill the cell (Abrami et al., 2000). The α-toxin secreted by the Gram-positive bacterium Clostridium septicum (Tweten and Sellman, 1999) also binds to GPI-anchored proteins and kills the cell in a similar way to aerolysin (Parker et al., 1996; Gordon et al., 1999). The two toxins share homologous protein sequences and characteristics, such as activation upon cleavage of a C-terminal peptide and the formation of oligomeric channels (Ballard et al., 1995; Gordon et al., 1997).

A major difference between them is that aerolysin has a two-lobe structure, an N-terminal small lobe (SL) and a C-terminal large lobe (LL) (Parker et al., 1994), whereas the clostridial α-toxin has only a single, LL-like structure (Ballard et al., 1995). SL has homology to the S2 and S3 subunits of pertussis toxin of Bordetella pertussis, forming a family of domains, termed APT domains. APT domains have homology to carbohydrate recognition domains of C-type lectins (Rossjohn et al., 1997). Aerolysin bearing a mutation in SL has reduced receptor-binding ability (Rossjohn et al., 1997). A hybrid toxin (HT), consisting of SL of aerolysin linked to α-toxin, had much greater lytic activity than the α-toxin (Diep et al., 1999). Taken together, SL may have a carbohydrate-binding site that contributes to the binding of aerolysin to target cells.

Although the GPI anchor is clearly the most important determinant of aerolysin binding (Diep et al., 1998b), it alone is not sufficient for the binding (Abrami et al., 2002). It is also known that aerolysin binds weakly to glyco phorin A (GPA), a heavily glycosylated erythrocyte membrane protein that is not GPI anchored. HT, but not the α-toxin, is also able to bind to GPA (Diep et al., 1999). Therefore, the SL domain may recognize a second determinant in addition to the GPI anchor.

In order to obtain new GPI-deficient mutants from CHO cells, we used aerolysin as a tool. To our surprise, one of the aerolysin-resistant mutants expressed normal levels of GPI-anchored proteins. Here, we report that this mutant is defective in the processing of N-glycan, that aerolysin recognizes N-glycan on GPI-anchored proteins with SL and that the binding of α-toxin is independent of N-glycan.

Results

Derivation and classification of aerolysin-resistant mutant CHO cells

Aiming to obtain new mutant cells defective in GPI biosynthesis, we selected aerolysin-resistant clones from chemically mutagenized CHO(wt) cells [see Materials and methods for CHO(wt) cells]. We obtained 22 clones resistant to 5 nM proaerolysin. They were classified into three groups based on profiles of CD59 and decay-accelerating factor (DAF) expression on the cell surface and of the accumulated GPI intermediates.

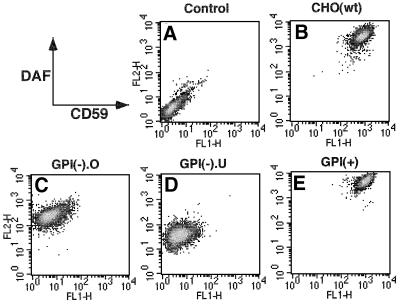

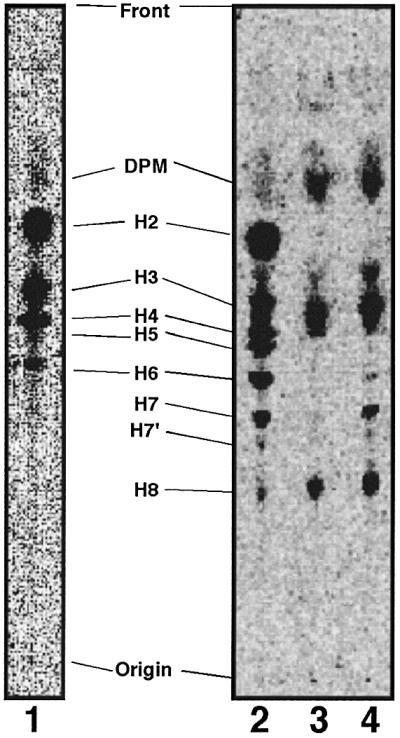

Twelve of 22 clones belonging to the first group, termed GPI(–).O cells, expressed no CD59 and 10% of the normal level of DAF (Figure 1C). Upon metabolic labeling with [3H]mannose, they accumulated GPI intermediates H2–H6 (Figure 2, lane 1), suggesting a defect in the transfer of ethanolaminephosphate to the third mannose. Consistent with this, PIG-O cDNA (Hong et al., 2000) restored the expression of CD59 and DAF after transfection (data not shown).

Fig. 1. Different expressions of GPI-anchored proteins on three aerolysin-resistant mutant cells. Cells were stained for CD59 and DAF. (A) Control, wild-type CHO cells stained with isotype-matched non-relevant antibodies. (B) CHO(wt), wild-type CHO cells. (C) GPI(–).O, GPI-anchor-deficient CHO cells. (D) GPI(–).U, CHO cells defective in GPI transamidase. (E) GPI(+), GPI-anchor-sufficient, aerolysin-resistant CHO cells.

Fig. 2. Aerolysin-resistant GPI(+) cells are not defective in GPI biosynthesis. Lipids extracted from cells metabolically labeled with [3H]mannose were analyzed by TLC in a solvent consisting of CHCl3:MeOH:H2O = 10:10:3. Mannolipids termed according to Hirose et al. (1992) are indicated. Lane 1, mutant GPI(–).O; lane 2, mutant GPI(–).U; lane 3, mutant GPI(+); lane 4, wild-type CHO(wt) cells.

Six clones belonging to the second group, termed GPI(–).U cells, expressed no CD59 and a very low level of DAF (Figure 1D). They represent a new group of mutants because the expressions of CD59 and DAF were not recovered by transfection of any cDNAs of known genes involved in the biosynthesis of and attachment to GPI (data not shown). They accumulated all GPI intermediates (Figure 2, lane 2) like mutant cells defective in GPI transamidase (Ohishi et al., 2000).

Surprisingly, 4 of 22 clones belonging to the third group, termed GPI(+) cells, expressed CD59 and DAF at normal levels (Figure 1E) and had a normal profile of GPI intermediates (Figure 2, lane 3 versus 4). The CD59 and DAF on GPI(+) cells were as sensitive to phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C as those on CHO(wt) cells (data not shown). Therefore, GPI(+) cells expressed normal levels of GPI-anchored proteins on the cell surface, but nevertheless were resistant to aerolysin, which utilizes GPI-anchored proteins as receptors.

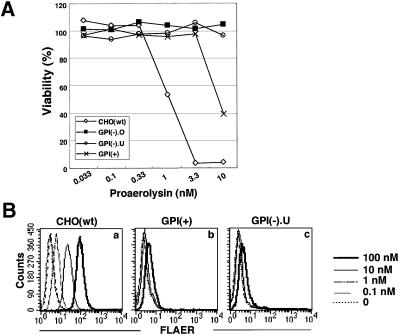

GPI(+) cells do not bind aerolysin

We compared the resistance of three mutant cells to proaerolysin. Cells defective in the surface expression of GPI-anchored proteins, GPI(–).O and GPI(–).U, were not killed by 10 nM aerolysin, whereas 60% of GPI(+) and all CHO(wt) cells were killed. About 50% of CHO(wt) cells were killed at 1 nM, indicating that GPI(+) cells were ∼10 times more resistant than CHO(wt) cells (Figure 3A). The GPI-deficient CHO cells were 100–1000 times more resistant than CHO(wt) cells (data not shown). So, GPI(+) cells had intermediate resistance to aerolysin.

Fig. 3. The aerolysin resistance of GPI(+) cells was due to the inefficient binding of the toxin. (A) Viabilities of mutant CHO cells after treatments with increasing concentrations of aerolysin. Percent cell viability measured by MTT assay is shown as a function of the proaerolysin concentration. (B) Binding of fluorescent-tagged proaerolysin (FLAER) to mutant cells. Cells incubated with FLAER at various concentrations (shown on the right) were analyzed by flow cytometry. (a) CHO(wt); (b) GPI(+); (c) GPI(–).U cells.

We then tested the binding of FLAER, an Alexa488-conjugated mutant proaerolysin that binds to the receptors but does not kill the cell (Brodsky et al., 2000). FLAER bound to CHO(wt) but not to GPI(–).O (data not shown) nor to GPI(–).U cells (Figure 3B, a and c), as expected. FLAER also did not bind to GPI(+) cells, even at 100 nM (Figure 3B, b). Therefore, despite a normal expression of GPI-anchored proteins, GPI(+) cells do not bind aerolysin efficiently.

GPI(+) cells are defective in the maturation of N-glycan due to a defect in N-acetylglucosamine transferase I (GnTI)

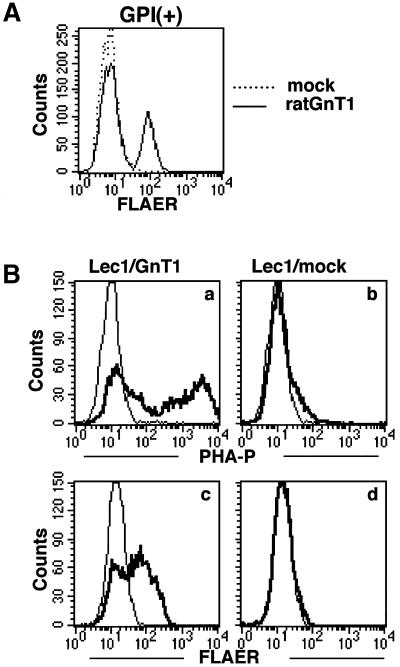

To clone the gene responsible for the decreased sensitivity of GPI(+) cells to aerolysin, we used FLAER as a staining tool in the expression cloning. We transfected a rat cDNA library into the GPI(+) cells, collected cells in which the binding of FLAER was restored, and recovered cDNAs from them. We obtained cDNA clones that restored binding of FLAER to GPI(+) cells (Figure 4A). They encoded GnTI, a glycosyltransferase involved in maturation of N-glycans (Kumar et al., 1990).

Fig. 4. GPI(+) cells are defective in GnTI. (A) GnTI cDNA restored binding of FLAER to GPI(+) cells. GPI(+) cells transfected with rat GnTI cDNA (solid line) or a mock vector (dotted line) were stained with 5 nM FLAER and analyzed by FACS. (B) Lec1 CHO cells, an authentic GnTI mutant, are defective in aerolysin binding, similar to GPI(+) mutant. Lec1 cells transiently transfected with GnTI cDNA (a and c) or a mock vector (b and d) were incubated with 10 µg/ml FITC–PHA-P (a and b) or 5 nM FLAER (c and d). Thin lines, untransfected Lec1 cells; bold lines, transfectants.

Lec1 CHO cells are defective in GnTI and do not make complex-type N-glycan (Puthalakath et al., 1996). We transiently transfected Lec1 cells with GnTI or a mock vector. The cells transfected with the mock vector did not bind fluorescent-labeled phytohemagglutinin-P (PHA-P) due to a lack of complex-type N-glycan. The cells transfected with GnTI efficiently bound PHA-P, indicating restoration of the complex-type N-glycan (Figure 4B, a and b). The mock-transfected Lec1 cells did not bind FLAER, whereas the GnTI-transfected Lec1 cells did (Figure 4B, c and d). It is, therefore, indicated that efficient aerolysin binding requires GnTI-dependent maturation of N-glycan.

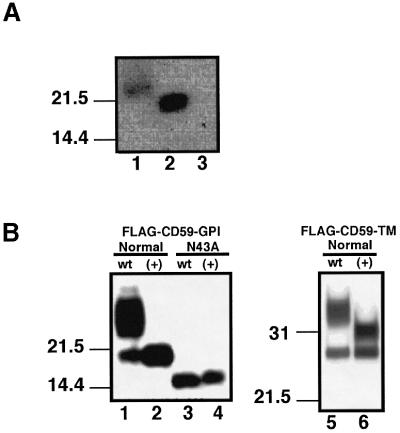

We then tested N-glycan of GPI(+) cells. We immunoprecipitated CD59, which has one N-glycosylation site (Bodian et al., 1997), and analyzed it by western blotting (Figure 5A). CD59 was 2–3 kDa smaller in GPI(+) cells than in wild-type cells (lanes 1 and 2), and was not detected in GPI(–).U cells (lane 3), consistent with the FACS data shown in Figure 1. To confirm that the smaller size of CD59 in GPI(+) cells was due to immature N-glycan, we transfected an N-glycan-less (N43A) mutant of FLAG-tagged CD59 into CHO(wt) and GPI(+) cells. As expected, the N-glycan-less CD59 expressed in the two cells had a similar size (Figure 5B, lanes 3 and 4). Wild-type FLAG-tagged CD59 expressed in GPI(+) cells was 2–3 kDa smaller than the major form expressed in CHO(wt) cells (lanes 1 and 2). To eliminate the possibility that the smaller size of CD59 in GPI(+) cells was due to some unknown abnormality in the GPI-anchor structure, we used FLAG-tagged CD59-TM with the transmembrane domain of CD46 (Lublin et al., 1988) in place of the C-terminal GPI attachment signal. The FLAG-tagged CD59-TM expressed in GPI(+) cells was 2–3 kDa smaller than the major form in CHO(wt) cells (lanes 5 and 6). These results indicated clearly that GPI(+) cells are indeed defective in N-glycan maturation, like Lec1 cells, accounting for their resistance to aerolysin.

Fig. 5. GPI(+) cells are defective in maturation of N-glycan. (A) Expression of a smaller CD59 by GPI(+) mutant cells. CD59 immunoprecipitates from NP-40 extracts of wild-type CHO(wt) (lane 1), GPI(+) mutant (lane 2) and GPI(–).U mutant (lane 3) cells were analyzed by western blotting with anti-CD59 mAb. Size makers are shown on the left. (B) The smaller sized CD59 in GPI(+) cells was due to an abnormal N-glycan not GPI anchor. Left panel: wild-type CHO cells (lanes 1 and 3) and GPI(+) mutant CHO cells (lanes 2 and 4) were transfected with a FLAG-tagged GPI-anchored form of CD59 (lanes 1 and 2) or its non-N-glycosylation mutant (N43A) (lanes 3 and 4). Two days later, proteins were immunoprecipitated by anti-CD59 mAb, followed by western blotting against anti-FLAG mAb. Right panel: a FLAG-tagged transmembrane form of CD59 was transfected instead of the FLAG-tagged GPI-anchored form. FLAG-tagged transmembrane CD59 was transfected into wild-type (lane 5) and GPI(+) mutant (lane 6) CHO cells.

Aerolysin does not efficiently bind to swainsonine-treated cells

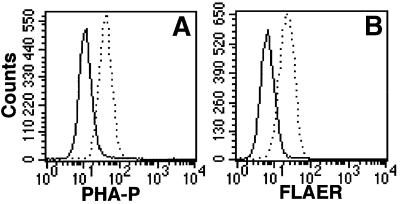

We next studied what structure in N-glycan is required for the efficient aerolysin binding. First, we treated CHO(wt) cells with swainsonine, which inhibits α-mannosidase II, the enzyme that acts immediately next to GnTI in N-glycan maturation (Tulsiani and Touster, 1983; Merkle et al., 1985; Foddy et al., 1986). The swainsonine treatment decreased binding of PHA-P, confirming the inhibition of N-glycan maturation (Figure 6A). The cells treated with swainsonine inefficiently bound FLAER, compared with buffer-treated cells (Figure 6B). It is, therefore, indicated that elimination of mannose(s) by α-mannosidase II is required for the efficient binding of aerolysin (Table I).

Fig. 6. Inefficient binding of proaerolysin to cells treated with swainsonine. To inhibit α-mannosidase II, wild-type CHO cells were treated with 10 µg/ml swainsonine or PBS for 3 days and then incubated with 10 µg/ml FITC-conjugated PHA-P (A) and 5 nM FLAER (B). Solid lines, swainsonine-treated cells; dotted lines, buffer-treated cells.

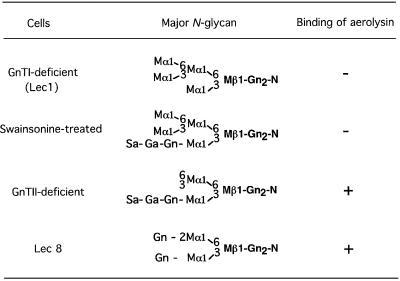

Table I. Structure and aerolysin-binding ability of N-glycan.

M, mannose; N, asparagine; Gn, N-acetylgucosamine; Ga, galactose; Sa, sialic acid.

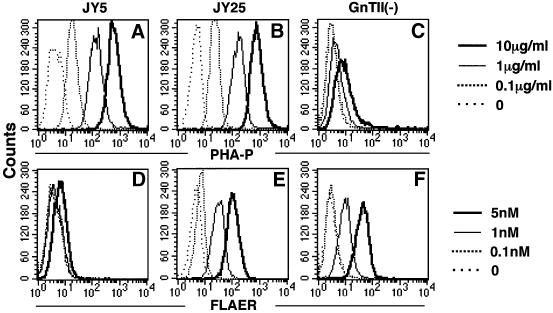

The enzyme that acts next to α-mannosidase II is N-acetylglucosamine transferase II (GnTII) (Tan et al., 1995). A deficiency of GnTII causes congenital disorder of glycosylation (CDG) type IIa (Schachter and Jaeken, 1999; Aebi and Hennet, 2001). We used lymphoblastoid cells obtained from a patient with CDG type IIa (Tan et al., 1995). As positive and negative controls, we used wild-type JY25 and GPI-deficient JY5, EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cells (Hollander et al., 1988). The GnTII-deficient cells bound PHA-P inefficiently compared with JY25 and JY5, as expected (Figure 7A–C). When stained with FLAER, GPI-deficient JY5 cells did not bind FLAER, as for other GPI-deficient cells. In contrast, GnTII-deficient cells bound FLAER as well as did wild-type JY25 cells (Figure 7D–F). Therefore, the action of GnTII is not required for efficient binding of aerolysin (Table I).

Fig. 7. Deficiency of GnTII does not affect binding of proaerolysin. GPI-deficient B-lymphoblastoid cells (JY5), the wild-type counterpart (JY25) and B-lymphoblastoid cells from a patient with GnTII deficiency [GnTII(–)] were incubated with PHA-P (A–C) and FLAER (D–F) at various concentrations (shown on the right).

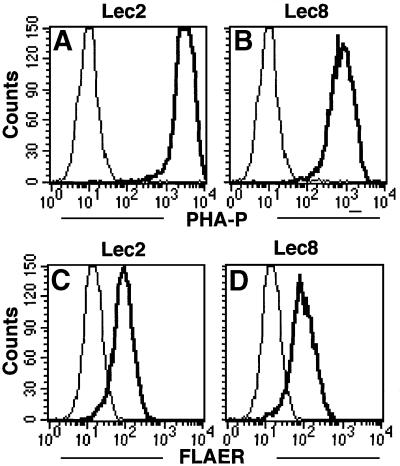

We also tested Lec8 and Lec2 CHO cells that are deficient in the terminal galactose and sialic acid, respectively, due to the defects in UDP-galactose and CMP-sialic acid transporters, respectively (Deutscher et al., 1984; Oelmann et al., 2001). We compared them with Lec1 CHO cells. The rank order for binding to PHA-P was Lec2 > Lec8 >> Lec1, as expected (Figures 8A, B and 4B, b). Lec2 and Lec8 (Figure 8C and D) but not Lec1 (Figure 4B, d) cells bound FLAER efficiently, indicating that the addition of galactose to N-acetylglucosamine is not required for the efficient binding of aerolysin (Table I). Lec2, Lec8 and wild-type cells were similarly sensitive to aerolysin (data not shown).

Fig. 8. Normal binding of aerolysin to Lec2 and Lec8 cells. (A and B) Binding of fluorescent-tagged PHA-P (10 µg/ml) to Lec2 (A) and Lec8 (B) cells. Bold lines, PHA-P; thin lines, PBS. (C and D) FLAER binding to Lec2 and Lec8 cells. Cells were incubated with 5 nM FLAER. Bold lines, FLAER; thin lines, PBS.

Taken together, these results indicate that aerolysin binding is dependent upon N-glycan maturation, specifically α-mannosidase II-dependent removal of mannose(s) from Gn-M5-Gn2-N (Gn, N-acetylglucosamine; M, mannose; N, asparagine). Since galactose is not required, the minimum N-glycan structure for aerolysin binding would be Gn-M3-Gn2-N.

N-glycan in GPA is a binding determinant for aerolysin

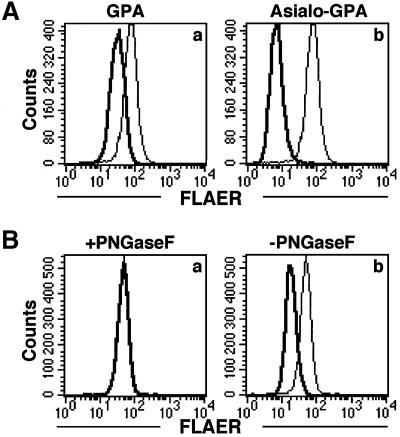

Because GPA binds aerolysin weakly, it inhibits binding of aerolysin to the cell surface (Garland and Buckley, 1988). Although GPA is not GPI anchored, it is highly glycosylated (60% of its weight is due to a single N-glycan and 15 O-glycans) (Dill et al., 1990). We tested whether asialo-GPA inhibits aerolysin binding as well as does GPA (Figure 9). When FLAER was pre-incubated with GPA or asialo-GPA, its binding to CHO(+) cells was inhibited by both GPA (Figure 9A, a) and asialo-GPA (Figure 9A, b). Asialo-GPA was more inhibitory on a molar basis, indicating that sialic acid is not required for the association of GPA with aerolysin.

Fig. 9. N-glycan of GPA is the binding determinant for aerolysin. (A) GPA and asialo GPA inhibited binding of FLAER to CHO cells. FLAER (5 nM) was pre-incubated with GPA, asialo-GPA (0.5 mg/ml) or buffer for 10 min, and then incubated with CHO cells. Thin lines, buffer-treated FLAER; bold lines, GPA-treated (a) and asialo GPA-treated (b) FLAER. (B) Treatment with PNGase F abolished the inhibitory activity of asialo GPA. Samples of asialo-GPA (0.3 mg/ml) treated with PNGase F or buffer only were incubated with FLAER (5 nM) for 10 min. The mixtures were then incubated with CHO cells. Thin lines, binding of non-treated FLAER; bold lines, binding of FLAER in the presence of PNGase F-treated asialo GPA (a) or buffer-treated asialo GPA (b).

To test whether the N- or the O-glycan of GPA is responsible for the inhibition of aerolysin binding, we digested asialo-GPA with either peptide N-glycanase F (PNGase F) or O-glycanase. The inhibitory activity of asialo-GPA against FLAER disappeared after PNGase F treatment (Figure 9B, a and b), but not O-glycanase treatment (data not shown). PNGase F did not affect the protein portion of asialo-GPA since silver-stained bands before and after the enzyme treatment had similar intensities. We obtained similar results with GPA (data not shown). These observations indicate that N-glycan of GPA is responsible for the association with aerolysin.

SL domain of aerolysin recognizes N-glycan on GPI-anchored proteins

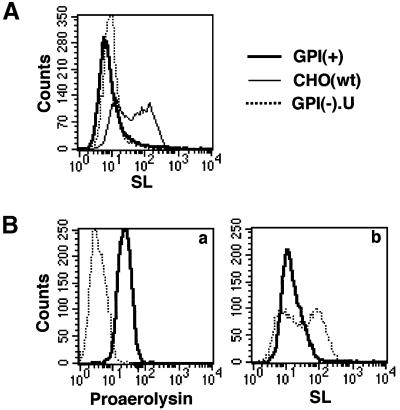

Because the SL of aerolysin has an APT-fold structure similar to C-type lectins (Rossjohn et al., 1997), we hypothesized that it is this domain that interacts with N-glycan. To test this possibility, we prepared a fluorescently labeled SL. SL at 1 µM could bind to CHO(wt) cells significantly, but not to GPI(+) and GPI(–).U cells (Figure 10A). SL, therefore, binds to N-glycans on GPI-anchored proteins, but not to those on other proteins. Since proaerolysin (FLAER) can bind efficiently to CHO(wt) cells at 1 nM (Figure 3B), it appears that the full-length toxin has a 1000-fold higher affinity than SL for GPI-anchored proteins, in agreement with a previous report (MacKenzie et al., 1999).

Fig. 10. Binding of SL to N-glycan of GPI-anchored proteins. (A) Fluorescent-tagged SL bound to wild-type CHO cells (thin line) but not to GnTI-deficient GPI(+) cells (bold line) and GPI(–).U cells (dotted line). (B) SL recognized the same binding determinant as intact aerolysin. CHO(wt) cells were incubated with biotinylated proaerolysin (10 nM) (bold line) or PBS (dotted line) plus streptavidin–PE in the first step (a). In the second step, the cells were incubated with 10 µM fluorescent-tagged SL (b; bold line, cells pre-treated with biotinylated aerolysin; dotted line, cells pre-treated with PBS).

To determine whether the isolated SL and the intact toxin recognize the same site on the receptors, we performed competition assays between SL and aerolysin (Figure 10B). When CHO(wt) cells were pre-incubated with 10 nM biotinylated proaerolysin (Figure 10B, a), the subsequent binding of SL at 10 µM was nearly completely inhibited (Figure 10B, b). Therefore, SL and the intact toxin recognize the same determinant, N-glycan on GPI-anchored proteins.

Clostridium septicum α-toxin does not recognize N-glycan on GPI-anchored proteins

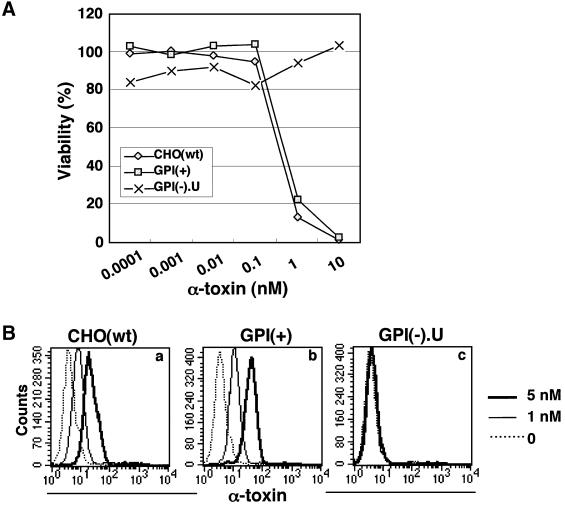

The α-toxin of C.septicum is homologous to the LL domain of aerolysin (Ballard et al., 1995) and also recognizes GPI-anchored proteins on the cell surface (Gordon et al., 1999). To test whether this toxin recognizes N-glycan, like aerolysin, we assayed the killing of GPI(+) cells by the α-toxin (Figure 11A). In contrast to what was observed for aerolysin, GPI(+) and CHO(wt) cells showed a similar sensitivity to the α-toxin. GPI-deficient GPI(–).U cells were resistant to up to 10 nM α-toxin, as expected. We next stained the cells with fluorescent-labeled α-toxin. In agreement with the cell viability assay, GPI(+) and CHO(wt) cells efficiently bound α-toxin, whereas GPI(–).U cells did not (Figure 11B, a–c). These results indicated that α-toxin does not recognize N-glycan on GPI-anchored proteins.

Fig. 11. No requirement of N-glycan for the binding of C.septicum α-toxin. (A) GPI(+) cells were as sensitive to α-toxin as CHO(wt) cells. Percent viability is plotted as a function of the α-toxin concentration. (B) Efficient binding of α-toxin to GPI(+) cells. CHO(wt) cells (a), GPI(+) mutant (b) and GPI(–).U mutant (c) cells were incubated with various concentrations of fluorescent-tagged α-toxin.

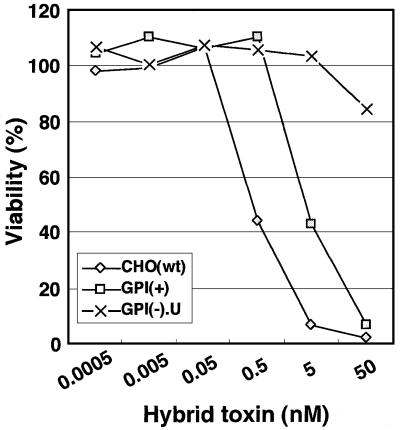

The main structural difference between aerolysin and the α-toxin is the presence of the N-terminal SL domain in aerolysin. It was reported previously that a hybrid toxin consisting of SL fused to the N-terminus of α-toxin was much more active than the α-toxin against human erythrocytes and mouse T lymphocytes (Diep et al., 1999). We thought that such a hybrid toxin might have a killing profile similar to aerolysin. In fact, CHO(wt) cells were 10 times more sensitive than GPI(+) cells to the hybrid toxin (Figure 12), indicating that SL increased the binding affinity through its ability to recognize N-glycan.

Fig. 12. CHO(wt) cells were 10-fold more sensitive to hybrid toxin consisting of SL and α-toxin than GPI(+) cells. CHO(wt), GPI(+) mutant and GPI(–).U mutant cells were incubated with the hybrid toxin. Percent cell viability determined by MTT assay is plotted as a function of the toxin concentration.

Discussion

A major finding of this study is that N-glycan on GPI-anchored proteins is required for efficient binding of aerolysin. We found that CHO cells defective in GnTI, and CHO cells treated with swainsonine, bound aerolysin inefficiently (Table I). The recognition of N-glycan by aerolysin is also supported by the observation that pre-incubation with GPA but not PNGase F-treated GPA reduced the binding of aerolysin to the cell surface. In contrast, B-lymphoblastoid cells deficient in GnTII, and CHO cells defective in the addition of galactose (Lec8 cells), bound aerolysin normally (Table I). Therefore, for efficient binding of aerolysin, α-mannosidase II must remove mannoses from the mannose that is linked via an α1,6 bond to the β-linked mannose, whereas the addition of galactose to the N-acetylglucosamine that is added by GnTI is not required. We concluded that Gn-M3-Gn2-N is the minimum structural requirement and that a hydroxyl group at either position 3, 6 or both of α-mannose linked to the 6-position of β-mannose should be open (Table I).

Recently, it was reported that C2 toxin of Clostridium botulinum binds to N-glycan (Eckhardt et al., 2000). Similarly to aerolysin, GnT1-deficient CHO cells and swainsonine-treated CHO cells were more resistant to C2 toxin, indicating that Gn-M3-Gn2-N is also the minimum structural requirement for binding of C2 toxin (Eckhardt et al., 2000).

Two of the present results demonstrate that SL bears a binding site for N-glycan. First, recombinant SL, although only at very high concentrations, bound to wild-type but not to GnTI-deficient CHO cells (Figure 10). Secondly, HT consisting of SL and the α-toxin killed wild-type CHO cells more efficiently than GnTI-deficient CHO cells (Figure 12). These results are consistent with reports that SL has structural similarity to carbohydrate recognition domains of C-type lectins (Rossjohn et al., 1997) and that SL has a binding site for a carbohydrate determinant different from GPI (Diep et al., 1999). SL consists of two three-stranded antiparallel β-sheets and two α-helices (Rossjohn et al., 1997). All six strands and one of the two α-helices are superimposable on those of the carbohydrate recognition domain of mannose-binding protein, a C-type lectin (Rossjohn et al., 1997). The carbohydrate recognition domain of the mannose-binding protein bears a binding site for one sugar unit (Weis et al., 1992), suggesting that SL binds to a monosaccharide unit, most likely the mannose that is linked via an α1,6 bond to the β-linked mannose.

The binding of Alexa488-conjugated SL to CHO cells was nearly completely prevented by pre-incubation of the cells with FLAER, indicating that the isolated SL binds to the same site as does SL in the whole toxin (Figure 10). Moreover, the isolated SL did not bind to CHO cells defective in GPI-anchored proteins. Therefore, SL binds to N-glycans on GPI-anchored proteins but not to those on non-GPI-anchored proteins. It is clear that LL has the major binding site for GPI (Diep et al., 1999), but the present result suggests that SL also recognizes the GPI anchor together with N-glycan. Alternatively, SL binds to N-glycan that interacts with the GPI portion in such a way that it generates a binding determinant for SL.

In contrast to aerolysin, the α-toxin of C.septicum does not differentiate GnTI-deficient CHO cells from the wild-type cells (Figure 11). When SL is connected to α-toxin, HT kills the wild-type cells more efficiently than GnTI-deficient cells, indicating that the ability to recognize N-glycan is endowed (Figure 12). There are reports that the HT is more active than α-toxin (Diep et al., 1998a) and that LL has a lower binding affinity than the intact aerolysin (Diep et al., 1999). These observations imply that SL increases the receptor-binding affinities of the α-toxin and LL. This would account for the higher binding affinity of aerolysin than of α-toxin. Therefore, the different domain compositions of aerolysin and α-toxin correlate with the different receptor recognition characteristics.

The recognition of N-glycan by SL would be in line with the observation that not all GPI-anchored proteins are receptors for aerolysin (Gordon et al., 1999; Abrami et al., 2002). Because the dual recognition by LL and SL generates high affinity, the N-glycan that is involved in toxin binding should be properly oriented in the vicinity of the GPI anchor. Some of the GPI-anchored proteins would not have N-glycan and GPI in such an orientation.

Since we mainly used CHO cells in this study, it is possible that some GPI-anchored proteins on other cell types have high affinity for aerolysin without involving N-glycan. There is a report that enzymatic removal of N-glycans from mouse Thy-1 did not affect the binding of aerolysin, as determined by means of surface plasmon resonance (MacKenzie et al., 1999). The binding of aerolysin to the GPI anchor may be modulated by the protein portion of the receptor, resulting in various affinities for the toxin. Such an N-glycan-independent mechanism may be involved in determination of the affinities of aerolysin and the α-toxin to various GPI-anchored proteins.

Materials and methods

Cells and reagents

Human B-lymphoblastoid cells, JY25 and JY5 (Hollander et al., 1988), were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco’s MEM containing 10% FCS. The GnTII-deficient B-lymphoblastoid cell line from a patient with CDG type IIa was a gift from Dr H.Schachter (University of Toronto) and cultured in RPMI1640 medium containing 20% FCS and 1 mM pyruvate. Lec1, Lec2 and Lec8 cells were purchased from ATCC and cultured in α-MEM containing 10% FCS.

Proaerolysin, FLAER and biotinylated proaerolysin were obtained from Protox Biotech (Victoria, Canada). Ethyl-methanesulfonate (EMS), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), PNGase F, GPA, asialoglycophorin A, FITC-conjugated PHA-P and biotinylated anti-FLAG antibody were from Sigma. Swainsonine was purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan).

Derivation of aerolysin-resistant mutants of CHO cells

CHO cells defective in PIG-L and DPM2 genes were previously isolated upon selection with aerolysin (Abrami et al., 2001). Mutants defective in SL15 were also isolated from CHO cells using other screening procedures (Ware and Lehrman, 1996). In order to prevent the isolation of known mutants, we first generated parental CHO cells bearing cDNAs of PIG-L, DPM2 and SL15 as well as PIG-A, an X-linked gene. As a recipient of these cDNAs, we used the IIIB2A line of CHO-K1 cells expressing CD59 and DAF as marker GPI-anchored proteins (Nakamura et al., 1997). We stably transfected IIIB2A cells with FLAG-tagged PIG-L (Nakamura et al., 1997), GST-tagged DPM2, FLAG-tagged SL15 (Maeda et al., 1998) and GST-tagged PIG-A (Watanabe et al., 1996) cDNAs cloned in pME expression vectors (Maeda et al., 1998) and selected one clone that expressed four proteins, as assessed by western blotting with anti-tag antibodies. These parental cells, termed CHO(wt) cells, were cultured in Ham’s F-12 medium containing 10%FCS, 600 µg/ml G418, 200 µg/ml hygromycin and 5 µg/ml puromycin to ensure maintenance of the cDNAs. For mutagenesis, CHO(wt) cells (1 × 107 in a 15 cm dish) were treated with 400 µg/ml EMS for 48 h, washed and cultured for two more days. The treated cells were distributed into four 12-well plates (2.5 × 105 cells/well) and cultured for 1.5 days. They were then treated with 1 nM proaerolysin for 2 days, washed and cultured for 2 days. Viable cells were retreated with 5 nM proaerolysin for 1 day and cloned by limiting dilution.

FACS analysis

Cells were stained for CD59 and DAF with anti-CD59 (5H8) plus FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and biotinylated anti-DAF (IA10) plus PE-conjugated streptavidin (Biomeda, Foster City, CA) (Nakamura et al., 1997). Cells were also stained with FITC-conjugated PHA-P, FLAER, Alexa488-conjugated α-toxin and Alexa488-conjugated SL (all dissolved in PBS). Stained cells were analyzed in a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

Cell viability assay

Cells (3 × 104/well) were cultured for 1 day in 96-well plates. On the next day, after removal of the medium, samples (100 µl) of prewarmed (at 37°C) toxin diluted in culture medium were added to the wells. After incubation for 3 h at 37 °C, the viable cells were assessed using MTT (Quinn et al., 1991). Absorption at 540 and 690 nm was measured by Multiskan MCC/340MKII microreader (Titertek) to determine the amount of blue tetrazolium salt. Percent viability was calculated as:

Plasmids

To express the GPI-anchored form of FLAG-tagged CD59, we prepared by PCR a cDNA of FLAG-tagged CD59 that consists of the N-terminal 27 amino acids of human CD59, the FLAG tag, the main part of CD59 (amino acids 26–102) and the GPI-attachment signal of mouse Thy-1 (amino acids 132–162), and cloned it into a mammalian expression vector pME, generating pME-FLAG-CD59-GPI. To make an N-glycan-less mutant of FLAG-tagged CD59, we substituted asparagine at residue 43 of CD59 with alanine using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene).

To construct FLAG-tagged CD59 with a transmembrane domain, an XhoI–XbaI fragment encoding a transmembrane domain of CD46 (residues 270–350) was introduced in place of a sequence encoding the GPI-attachment signal of pME-FLAG-CD59-GPI.

We amplified the SL sequence by PCR using an upstream vector primer (5′-TGGTACGACTCACTATAG) and the SLA-R primer (5′-GCACCTCGAGGTCGCCATCTGGAATATCCAG) from pET22b(+)-PA template, which contained the proaerolysin gene with N-terminal pelB signal and C-terminal His tag sequences. We subcloned SL into the XbaI–XhoI site of pBSII, then transferred the NcoI–XbaI fragment of this plasmid into an NcoI- and XbaI-cut pET22b(+) (Novagen) to generate pET22b(+)-SLA. The SL used in this study corresponds to the protein termed SLA (Diep et al., 1998a).

To construct a plasmid for HT consisting of SL and α-toxin, we amplified the SL and α-toxin sequences separately by PCR. To amplify the SL fragment, we used the vector primer, P2(RI) primer (5′-TAACGAATTCAACAGGATTGGTCGGATAACACCAGG) and pET22b(+)-PA as a template, and subcloned the product into an XbaI- and EcoRI-cut pBSII. We also amplified the α-toxin fragment using P3(RI) primer (5′-TAACGAATTCACAAATCTTGAAGAGGGGGGATATGC), AT(XI) primer (5′-CTGCACTCGAGTATATTATTAATTAATATCAATTTTTTATCA) and pCS21 containing the α-toxin gene (a gift from Dr Y.Dohi, Osaka University) (Imagawa et al., 1994) as a template, and subcloned it into an EcoRI- and XhoI-cut pBSII. Two fragments were ligated in an XbaI- and XhoI-cut pBSII. We then transferred the NcoI–XhoI fragment of this plasmid into an NcoI- and XbaI-cut pET22b(+), generating pET22b(+)-HT. The HT contains glutamine and phenylalanine between SL and the α-toxin, and has His tags at the C-terminus.

Purification of toxins

To express His-tagged SL in the periplasm, we transformed Escherichia coli BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RP (Stratagene) with pET22b(+)-SL. His-tagged SL was recovered from the bacteria and purified with a HiTrap column using the AKTA prime system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) following the instructions provided. To prepare His-tagged HT, we transformed E.coli BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RP with pET22b(+)-HT. His-tagged HT was solubilized by sonication because of the formation of inclusion bodies and purified with the HiTrap column.

The α-toxin was purified from the culture supernatant of C.septicum, strain KZ1003 (a gift from Dr Shinichi Nakamura, Kanazawa University, Japan). The toxin was precipitated from the supernatant of an 18 h culture in brain–heart infusion broth (Difco, Detroit, MI) by 60% saturated ammonium sulfate, dissolved in 10 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.0 and chromatographed on a cation exchanger SP-Toyopearl 650M. The purified preparation of the toxin gave a single protein band at a position corresponding to a mol. wt of 48 000 on SDS–PAGE. The mouse LD50 of the preparation was 120 ng of protein.

The His-tagged HT and SL were conjugated with Alexa488 according to the provider’s instructions (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).

Western blotting

CD59 was immunoprecipitated with anti-CD59 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (5H8) plus protein G–beads and analyzed by western blotting against biotinylated 5H8 antibody plus horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin. FLAG-tagged CD59 and FLAG-tagged CD59-TM were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG beads, followed by western blotting against biotinylated anti-FLAG (M2) antibody plus HRP-conjugated streptavidin.

Expression cloning

The gene responsible for GPI(+) cells was obtained by means of expression cloning (Nakamura et al., 1997). In brief, a mixture of 480 µg each of a rat C6 glioma cDNA library and pcDNA-PyT(ori–) (Nakamura et al., 1997) was transfected into 1.44 × 108 cells by electroporation. Two days later, transfected cells were stained with FLAER and the cells that bound FLAER were sorted using FACS-Vantage (Becton Dickinson). From the 183 cells collected, 520 independent plasmid clones were recovered. Pooled plasmids were transfected again with pcDNA-PyT(ori–) into GPI(+) cells for another round of cell sorting. Recovered plasmids were individually tested for their ability to restore binding of FLAER on GPI (+) cells. Active plasmids were purified and sequenced.

Enzyme treatments and analysis of GPI intermediates

Asialo-GPA and GPA (1 mg/ml) were treated with PNGase F (500 mU) or O-glycanase (40 mU) in 50 µl of PBS for 4 days at 37°C. In vivo labeling of cells with [3H]mannose and TLC of mannolipids were performed as described previously (Hong et al., 2000).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Harry Schachter for GnTII-deficient cells, Dr Yoshitane Dohi for pCS21 plasmid, Drs Yusuke Maeda and Hisashi Ashida for critically reading the manuscript, and Kohjiro Nakamura, Keiko Kinoshita and Fumiko Ishii for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. Y.H. was supported by a fellowship from the Japan Society for Promotion of Science.

References

- Abrami L., Fivaz,M. and van der Goot,F.G. (2000) Adventures of a pore-forming toxin at the target cell surface. Trends Microbiol., 8, 168–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrami L., Fivaz,M., Kobayashi,T., Kinoshita,T., Parton,R.G. and van der Goot,F.G. (2001) Cross-talk between caveolae and glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-rich domains. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 30729–30736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrami L., Velluz,M.C., Hong,Y., Ohishi,K., Mehlert,A., Ferguson,M., Kinoshita,T. and van der Goot,G.F. (2002) The glycan core of GPI-anchored proteins modulates aerolysin binding but is not sufficient: the polypeptide moiety is required for the toxin–receptor interaction. FEBS Lett., 512, 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aebi M. and Hennet,T. (2001) Congenital disorders of glycosylation: genetic model systems lead the way. Trends Cell Biol., 11, 136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard J., Crabtree,J., Roe,B.A. and Tweten,R.K. (1995) The primary structure of Clostridium septicum α-toxin exhibits similarity with that of Aeromonas hydrophila aerolysin. Infect. Immun., 63, 340–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodian D.L., Davis,S.J., Morgan,B.P. and Rushmere,N.K. (1997) Mutational analysis of the active site and antibody epitopes of the complement-inhibitory glycoprotein, CD59. J. Exp. Med., 185, 507–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky R.A., Mukhina,G.L., Nelson,K.L., Lawrence,T.S., Jones,R.J. and Buckley,J.T. (1999) Resistance of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria cells to the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-binding toxin aerolysin. Blood, 93, 1749–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky R.A., Mukhina,G.L., Li,S., Nelson,K.L., Chiurazzi,P.L., Buckley,J.T. and Borowitz,M.J. (2000) Improved detection and characterization of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria using fluorescent aerolysin. Am. J. Clin. Pathol., 114, 459–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley J.T. (1999) The channel-forming toxin aerolysin. In Alouf,J.E. and Freer,J.H. (eds), The Comprehensive Sourcebook of Bacterial Protein Toxins. Academic Press, London, UK, pp. 362–372.

- Cowell S., Aschauer,W., Gruber,H.J., Nelson,K.L. and Buckley,J.T. (1997) The erythrocyte receptor for the channel-forming toxin aerolysin is a novel glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein. Mol. Microbiol., 25, 343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher S.L., Nuwayhid,N., Stanley,P., Briles,E.I. and Hirschberg,C.B. (1984) Translocation across Golgi vesicle membranes: a CHO glycosylation mutant deficient in CMP-sialic acid transport. Cell, 39, 295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep D.B., Lawrence,T.S., Ausio,J., Howard,S.P. and Buckley,J.T. (1998a) Secretion and properties of the large and small lobes of the channel-forming toxin aerolysin. Mol. Microbiol., 30, 341–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep D.B., Nelson,K.L., Raja,S.M., Pleshak,E.N. and Buckley,J.T. (1998b) Glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors of membrane glyco proteins are binding determinants for the channel-forming toxin aerolysin. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 2355–2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep D.B., Nelson,K.L., Lawrence,T.S., Sellman,B.R., Tweten,R.K. and Buckley,J.T. (1999) Expression and properties of an aerolysin– Clostridium septicum α toxin hybrid protein. Mol. Microbiol., 31, 785–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill K., Hu,S.H., Berman,E., Pavia,A.A. and Lacombe,J.M. (1990) One- and two-dimensional NMR studies of the N-terminal portion of glycophorin A at 11.7 Tesla. J. Protein Chem., 9, 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt M., Barth,H., Blocker,D. and Aktories,K. (2000) Binding of Clostridium botulinum C2 toxin to asparagine-linked complex and hybrid carbohydrates. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 2328–2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foddy L., Feeney,J. and Hughes,R.C. (1986) Properties of baby-hamster kidney (BHK) cells treated with swainsonine, an inhibitor of glycoprotein processing. Comparison with ricin-resistant BHK-cell mutants. Biochem. J., 233, 697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontes W., Sousa,M.V., Aragao,J.B. and Morhy,L. (1997) Determination of the amino acid sequence of the plant cytolysin enterolobin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 347, 201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland W.J. and Buckley,J.T. (1988) The cytolytic toxin aerolysin must aggregate to disrupt erythrocytes and aggregation is stimulated by human glycophorin. Infect. Immun., 56, 1249–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon V.M., Benz,R., Fujii,K., Leppla,S.H. and Tweten,R.K. (1997) Clostridium septicum α-toxin is proteolytically activated by furin. Infect. Immun., 65, 4130–4134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon V.M., Nelson,K.L., Buckley,J.T., Stevens,V.L., Tweten,R.K., Elwood,P.C. and Leppla,S.H. (1999) Clostridium septicum α toxin uses glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein receptors. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 27274–27280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose S., Prince,G.M., Sevlever,D., Ravi,L., Rosenberry,T.L., Ueda,E. and Medof,M.E. (1992) Characterization of putative glycoinositol phospholipid anchor precursors in mammalian cells. Localization of phosphoethanolamine. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 16968–16974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander N., Selvaraj,P. and Springer,T.A. (1988) Biosynthesis and function of LFA-3 in human mutant cells deficient in phosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins. J. Immunol., 141, 4283–4290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y., Maeda,Y., Watanabe,R., Inoue,N., Ohishi,K. and Kinoshita,T. (2000) Requirement of PIG-F and PIG-O for transferring phosphoethanolamine to the third mannose in glycosylphos phatidylinositol. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 20911–20919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imagawa T., Dohi,Y. and Higashi,Y. (1994) Cloning, nucleotide sequence and expression of a hemolysin gene of Clostridium septicum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 117, 287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T. and Inoue,N. (2000) Dissecting and manipulating the pathway for glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchor biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol., 4, 632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T., Inoue,N. and Takeda,J. (1995) Defective glycosyl phosphatidylinositol anchor synthesis and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Adv. Immunol., 60, 57–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Yang,J., Larsen,R.D. and Stanley,P. (1990) Cloning and expression of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I, the medial Golgi transferase that initiates complex N-linked carbohydrate formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 9948–9952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lublin D.M., Liszewski,M.K., Post,T.W., Arce,M.A., Le Beau,M.M., Rebentisch,M.B., Lemons,L.S., Seya,T. and Atkinson,J.P. (1988) Molecular cloning and chromosomal localization of human membrane cofactor protein (MCP). Evidence for inclusion in the multigene family of complement-regulatory proteins. J. Exp. Med., 168, 181–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie C.R., Hirama,T. and Buckley,J.T. (1999) Analysis of receptor binding by the channel-forming toxin aerolysin using surface plasmon resonance. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 22604–22609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda Y., Tomita,S., Watanabe,R., Ohishi,K. and Kinoshita,T. (1998) DPM2 regulates biosynthesis of dolichol phosphate-mannose in mammalian cells: correct subcellular localization and stabilization of DPM1 and binding of dolichol phosphate. EMBO J., 17, 4920–4929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConville M.J. and Ferguson,M.A.J. (1993) The structure, biosynthesis and function of glycosylated phosphatidylinositols in the parasitic protozoa and higher eukaryotes. Biochem. J., 294, 305–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkle R.K., Elbein,A.D. and Heifetz,A. (1985) The effect of swainsonine and castanospermine on the sulfation of the oligosaccharide chains of N-linked glycoproteins. J. Biol. Chem., 260, 1083–1089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N., Inoue,N., Watanabe,R., Takahashi,M., Takeda,J., Stevens,V.L. and Kinoshita,T. (1997) Expression cloning of PIG-L, a candidate N-acetylglucosaminyl-phosphatidylinositol deacetylase. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 15834–15840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson K.L., Raja,S.M. and Buckley,J.T. (1997) The glycosylphos phatidylinositol-anchored surface glycoprotein Thy-1 is a receptor for the channel-forming toxin aerolysin. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 12170–12174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelmann S., Stanley,P. and Gerardy-Schahn,R. (2001) Point mutations identified in Lec8 Chinese hamster ovary glycosylation mutants that inactivate both the UDP-galactose and CMP-sialic acid transporters. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 26291–26300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohishi K., Inoue,N., Maeda,Y., Takeda,J., Riezman,H. and Kinoshita,T. (2000) Gaa1p and gpi8p are components of a glycosylphos phatidylinositol (GPI) transamidase that mediates attachment of GPI to proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell, 11, 1523–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker M.W., Buckley,J.T., Postma,J.P., Tucker,A.D., Leonard,K., Pattus,F. and Tsernoglou,D. (1994) Structure of the Aeromonas toxin proaerolysin in its water-soluble and membrane-channel states. Nature, 367, 292–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker M.W., van der Goot,F.G. and Buckley,J.T. (1996) Aerolysin—the ins and outs of a model channel-forming toxin. Mol. Microbiol., 19, 205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthalakath H., Burke,J. and Gleeson,P.A. (1996) Glycosylation defect in Lec1 Chinese hamster ovary mutant is due to a point mutation in N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I gene. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 27818–27822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn C.P., Singh,Y., Klimpel,K.R. and Leppla,S.H. (1991) Functional mapping of anthrax toxin lethal factor by in-frame insertion mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 20124–20130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossjohn J., Buckley,J.T., Hazes,B., Murzin,A.G., Read,R.J. and Parker,M.W. (1997) Aerolysin and pertussis toxin share a common receptor-binding domain. EMBO J., 16, 3426–3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter H. and Jaeken,J. (1999) Carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1455, 179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda J., Miyata,T., Kawagoe,K., Iida,Y., Endo,Y., Fujita,T., Takahashi,M., Kitani,T. and Kinoshita,T. (1993) Deficiency of the GPI anchor caused by a somatic mutation of the PIG-A gene in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Cell, 73, 703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J., D’Agostaro,A.F., Bendiak,B., Reck,F., Sarkar,M., Squire,J.A., Leong,P. and Schachter,H. (1995) The human UDP-N- acetylglucosamine: α-6-d-mannoside-β-1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase II gene (MGAT2). Cloning of genomic DNA, localization to chromosome 14q21, expression in insect cells and purification of the recombinant protein. Eur. J. Biochem., 231, 317–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarutani M., Itami,S., Okabe,M., Ikawa,M., Tezuka,T., Yoshikawa,K., Kinoshita,T. and Takeda,J. (1997) Tissue specific knock-out of the mouse Pig-a gene reveals important roles for GPI-anchored proteins in skin development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 7400–7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulsiani D.R. and Touster,O. (1983) Swainsonine causes the production of hybrid glycoproteins by human skin fibroblasts and rat liver Golgi preparations. J. Biol. Chem., 258, 7578–7585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tweten R.K. and Sellman,B.R. (1999) Clostridium septicum pore-forming and lethal α-toxin. In Alouf,J.E. and Freer,J.H. (eds), The Comprehensive Sourcebook of Bacterial Protein Toxins. Academic Press, London, UK, pp. 435–442.

- Ware F.E. and Lehrman,M.A. (1996) Expression cloning of a novel suppressor of the Lec15 and Lec35 glycosylation mutations of Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 13935–13938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe R., Kinoshita,T., Masaki,R., Yamamoto,A., Takeda,J. and Inoue,N. (1996) PIG-A and PIG-H, which participate in glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor biosynthesis, form a protein complex in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 26868–26875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis W.I., Drickamer,K. and Hendrickson,W.A. (1992) Structure of a C-type mannose-binding protein complexed with an oligosaccharide. Nature, 360, 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]