Abstract

Cdc37 has been shown to be required for the activity and stability of protein kinases that regulate different stages of cell cycle progression. However, little is known so far regarding interactions of Cdc37 with kinases that play a role in cell division. Here we show that the loss of function of Cdc37 in Drosophila leads to defects in mitosis and male meiosis, and that these phenotypes closely resemble those brought about by the inactivation of Aurora B. We provide evidence that Aurora B interacts with and requires the Cdc37/Hsp90 complex for its stability. We conclude that the Cdc37/Hsp90 complex modulates the function of Aurora B and that most of the phenotypes brought about by the loss of Cdc37 function can be explained by the inactivation of this kinase. These observations substantiate the role of Cdc37 as an upstream regulatory element of key cell cycle kinases.

Keywords: Aurora B/Cdc37/cell cycle/cytokinesis/mitosis

Introduction

Cell division in eukaryotes is regulated by mechanisms that are tightly controlled in both time and space (Pines, 1999). This control is exerted by an interplay of mitotic kinases and phosphatases (for an overview, see Nigg, 2001). So far, little is known about the components required to activate and to maintain this regulatory machinery. One such component is Cdc37. Initially isolated in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Reed, 1980), highly conserved homologues of Cdc37 were later identified in Drosophila (Cutforth and Rubin, 1994), vertebrates (Stepanova et al., 1996; Huang et al., 1998) and many other organisms (reviewed by Hunter and Poon, 1997; Stepanova et al., 1997). Cdc37 is often associated with members of the Hsp90 heat shock family and interacts with kinases involved in signal transduction, cell growth and differentiation, such as v-src (Dey et al., 1996), Raf (van der Straten et al., 1997; Silverstein et al., 1998; Grammatikakis et al., 1999), sevenless (Cutforth and Rubin, 1994), MPS1 (Schutz et al., 1997), Cdc28 (Gerber et al., 1995), cdk4 (Dai et al., 1996; Stepanova et al., 1996) and others. A genetic interaction has also been described for Cdc37 and cdc2 in Drosophila (Cutforth and Rubin, 1994). Cdc37 has, independent of Hsp90, an inherent chaperon activity, e.g. for casein kinase II (Kimura et al., 1997).

The knowledge we have so far about Cdc37 is limited in several aspects. First, little is known about the function of this protein in mitosis. Secondly, we do not know its spatial and temporal arrangement in the cell and last, but not least, it is likely that we are still missing important Cdc37 substrates (Hunter and Poon, 1997). Here we show that Cdc37 is required for chromosome condensation and segregation, central spindle formation and cytokinesis. We also show that Cdc37 interacts with and is required for the stability of Aurora B (the generic name for AIM-1, Aurora 1, AIR-2, ARK2, Aik2 and AIRK2; see Nigg, 2001), a kinase whose loss of function leads to phenotypes that are very similar to those brought about by inactivation of Cdc37. We propose that inactivation of Aurora B is the main cause of the abnormal phenotypes observed when Cdc37 is abrogated.

Results

Mutations in the Cdc37 gene cause cytokinesis failure in Drosophila spermatocytes

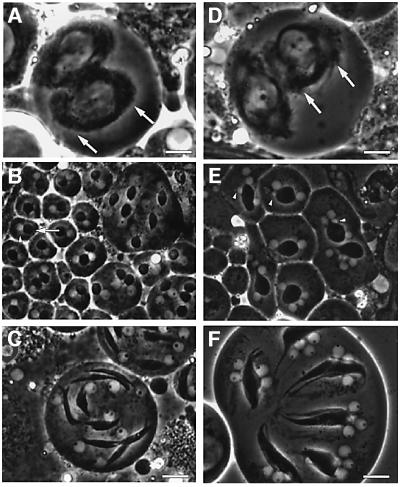

To study the function of Cdc37 we used four different mutant alleles, which were originally identified as lethal dominant enhancers of the sevenless mutation in Drosophila (Cutforth and Rubin, 1994). These alleles include an inversion (e1C), an in-frame deletion of amino acids 26–28 (e1E), a non-sense mutation leading to a stop codon after amino acid 6 (e4D) and a single amino acid replacement at position 338 (e6B). To determine the role of Cdc37 during cell division in Drosophila, we studied the phenotype of all three trans-heteroallelic combinations between the strong hypomorphic alleles Cdc37e1C, Cdc37e1E and Cdc37e4D and the weaker hypomorph Cdc37e6B (Cutforth and Rubin, 1994). All these combinations become lethal around the third instar larval stage, thus only allowing for the observation of male meiosis in Cdc37 mutant backgrounds at this stage. All three combinations at this stage have spermatids with a phenotype characteristic of cytokinesis failure. This is apparent in the four nuclei that are associated with a single mitochondrial derivative as the result of two meiotic cycles (Figure 1E and F) without cell division. In addition, the variant size of the nuclei (Figure 1E and F) is evidence for aberrant chromosome distribution between the nuclei in the meiotic division (Gonzalez et al., 1989; Fuller, 1993). Defects were also detected in the spindle morphology of the mutant cells, which were stumpy (Figure 1D) when compared with the control cells (Figure 1A). In spite of these major defects, spermatids with sperm tails are still formed (data not shown). The number and unequal size of the nuclei in the spermatids indicate not only a failure in cytokinesis but also argue for further defects in chromosome segregation. This led us to investigate the mechanism of chromosome segregation in live Drosophila spermatocytes.

Fig. 1. Mutations in the Cdc37 gene lead to failure of cytokinesis. Larval testis squash preparations of Drosophila visualized by phase microscopy. (A–C) Control heterozygous testis with: (A) normal metaphase spindle morphology (arrows indicate the length of metaphase spindle, scale bar = 8 µm); (B) single (phase bright) nuclei (arrowhead) attached to single (phase dark) mitochondrial derivatives (arrow) in spermatids; and (C) spermatids with elongating mitochondrial derivatives. Scale bar = 12 µm. (D–F) Transheterozygous mutant testis show: (D) abnormal stumpy shaped metaphase spindles (arrows indicate the length of metaphase spindle, scale bar = 8 µm); (E) multiple unequally sized nuclei (arrowheads) attached to mitochondrial derivatives in spermatids (small arrowheads mark micro-nuclei); and (F) four unequally sized nuclei (arrowheads) attached to single elongating mitochondrial derivatives. Scale bar = 12 µm.

Correct chromosome condensation, central spindle assembly and chromosome segregation in Drosophila spermatocytes requires functional Cdc37

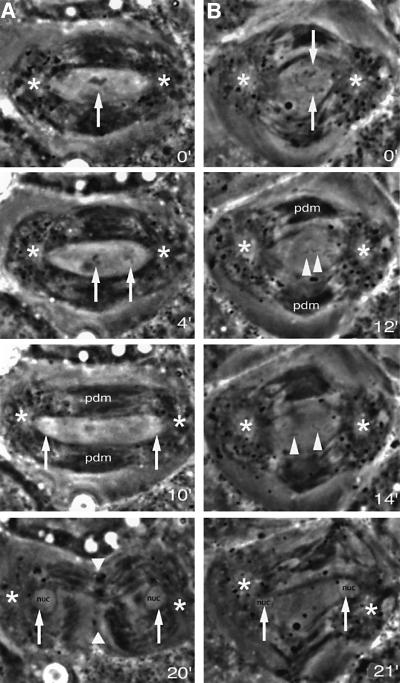

To further investigate the abnormal phenotypes brought about by mutation in Cdc37, we followed meiosis in mutant spermatocytes by time-lapse video microscopy (Rebollo and González, 2000). Heterozygous control larvae show normal chromosome condensation at prometaphase I (Supplementary videos 1 and 2, available at The EMBO Journal Online). Bivalents align properly at the metaphase plate during metaphase I (Figure 2A, time point 0′) and the homologues separate during anaphase I (Figure 2A, time point 4′). After segregation, the chromatin decondenses (Figure 2A, time point 10′) and the two daughter nuclei form at the time the cytokinesis furrow constricts the dividing cell (Figure 2A, time point 20′; Supplementary videos 1 and 2). This is in contrast to the mutants, where at anaphase I chromosomes are poorly condensed and often fail to align in a proper metaphase plate (Figure 2B, time point 0′; Supplementary video 3). The overall distance between the two centrosomes at metaphase is shorter (16.8 µm ± 0.9) than in control cells (20.5 µm ± 1.8) and the overall shape of the mutant spindle is stumpier (compare Figure 1A and D with 2B). During metaphase, the homologues split apart asynchronously and the first signs of splitting are observed 5.9 ± 2.7 min (N = 6) before the onset of poleward movement, earlier than in control cells (1.2 ± 0.8 min; N = 5). During anaphase, segregation mistakes are obvious. Some chromosomes acquire an amphitelic orientation (Figure 2B, time point 12′), i.e. with both sister kinetochores orientated to opposite poles (Roos, 1976). Premature sister chromatid separation takes place as the amphitelic chromosomes segregate their chromatids during anaphase I (Figure 2B, time point 14′). Single chromatids are also observed at different positions within the anaphase spindle (see Supplementary videos 3 and 4). After segregation the chromatin decondenses and the daughter nuclei are formed (Figure 2B, time point 21′; Supplementary videos 3 and 4). No sign of furrow constriction is detected and cytokinesis does not occur giving rise to binucleated cells (Figure 2B, time point 21′) that sometimes might contain additional micronuclei (Figure 1E and F).

Fig. 2. Chromosome condensation, chromosome segregation and cytokinesis fail in Cdc37 mutant spermatocytes. Video stills of Drosophila primary spermatocytes. The numbers indicate the time points (in minutes) corresponding to each still of the sequence. The full video sequences from which these stills have been taken are attached as Supplementary data (videos 1–4). (A) Control primary spermatocyte tracked from late metaphase I to the completion of cytokinesis. The bivalents (arrow) are fully condensed and aligned at the metaphase plate (time point 0′). At anaphase I (time point 4′), the homologues of each bivalent (arrows) move towards the poles. During anaphase B the chromatin becomes decondensed at the poles (arrows) as the spindle lengthens (time point 10′). Finally, the two daughter nuclei (arrows) are surrounded by the nuclear membrane and the cleavage furrow (arrowheads) has progressed far enough that two daughter cells can be distinguished (time point 20′). (B) Cdc37 mutant primary spermatocyte tracked from metaphase I to the end of the first meiotic division. At metaphase I the spindle is abnormally stumpy and the chromosomes are not fully condensed (time point 0′). The bivalents (arrows) are not aligned in a normal metaphase plate. After the onset of anaphase I (time point 12′) sister chromatid cohesion is released, signalled by the separated sister chromatids of the amphitelic chromosome (arrowheads), while the rest of the chromosomes have already reached the poles. Subsequently, the sister chromatids (arrowheads) move to the poles (time point 14′). The distribution of the parafusorial membranes and mitochondria around the spindle is distorted (time point 21′). The nuclear membrane is reformed around the two daughter nuclei but the cytokinesis furrow invagination is absent. As a result of the cytokinesis failure a binucleated cell is formed. pdm, phase dense parafusorial membranes; nuc, nucleus; ∗, centrosome.

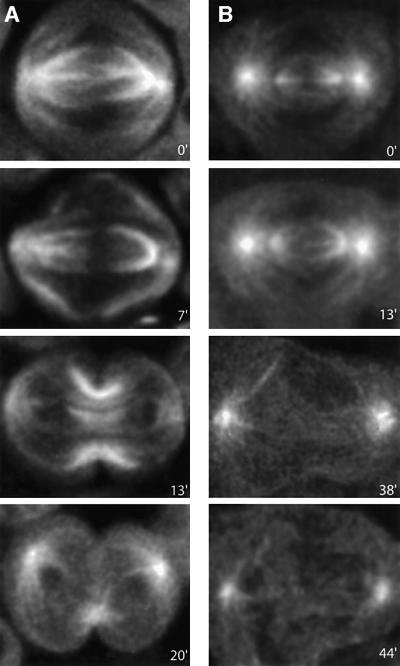

To assess the possible involvement of the spindle microtubules in chromosome mis-segregation and cytokinesis failure in Cdc37 mutants, we examined heteroallelic mutants in a GFP–α-tubulin background. Time-lapse analysis of spermatocytes (Figure 3; Supplementary videos 5 and 6) revealed four major defects. First, in the mutant cells (Figure 3B, time point 0) the kinetochore fibers are reduced both in size and in density compared with wild-type (Figure 3A, time point 0). Secondly, at late anaphase the dense bundles of microtubules that run along the membrane at the area where furrowing will occur in the control (Figure 3A, time point 7) are absent in the mutant cells (Figure 3B, time point 13). Thirdly, in the mutants no central spindle is formed (Figure 3B, time point 38) as opposed to the control cells (Figure 3A, time point 13). Finally, while the midbody can be clearly identified in control cells (Figure 3A, time point 20), it is absent in the Cdc37 mutant spermatocytes (Figure 3B, time point 44). From these observations, we concluded that several aspects of microtubule organization are severely disrupted in Cdc37 mutant spermatocytes and that these alterations contribute to the complex phenotype displayed. In particular, since it is well established that the central spindle is critical for cytokinesis (reviewed by Glotzer et al., 2001), its absence in the mutant spermatocytes is likely to be the cause of cytokinesis failure in these cells.

Fig. 3. The central spindle in Cdc37 mutants fails to be assembled properly. Real-time imaging of α-tubulin–GFP in control (A) and Cdc37 mutant (B) spermatocytes, followed from late metaphase I until the end of the first meiotic division. The full video sequences from which these stills have been taken are attached as Supplementary data (videos 5 and 6). (A, time point 0) Control spermatocytes show at metaphase I a well defined morphology of astral and kinetochore microtubule bundles. (B, time point 0) In the Cdc37 spermatocytes asters appear normal, but the spindle is reduced both in size and density of microtubules, especially the kinetochore fibers. (A, time point 7) During wild-type anaphase I, the spindle progressively depolymerizes between the two sets of migrating chromosomes, as microtubule density increases at the spindle poles. Dense bundles of microtubules appear at this stage, which run along the plasma membrane from the asters to the position where the cleavage furrow will be formed. These bundles are not observed in the Cdc37 mutants (A and B, time point 13) The central spindle becomes evident during the ingression of the cleavage furrow. The two incipient daughter nuclei can be seen as two dark areas at both spindle poles. (B, time point 38) No central spindle is formed in the Cdc37 spermatocytes. Instead, disorganized bundles of microtubules run from the asters to different positions of the cell surface, at a very delayed time point when compared with the central spindle formation in the control cells. (A, time point 20) At the end of cytokinesis the asters and the midbody can be observed in the control spermatocytes. (B, time point 44) Only the asters are evident in the Cdc37 spermatocytes at a time at which cytokinesis should have been completed long ago. The lack of a midbody is evident.

Cdc37 is known to act as a kinase-targeting subunit of the Hsp90 complex, therefore being required for the stability and activity of a number of kinases. It is thus likely that the phenotypes brought about by the inactivation of Cdc37 are due to the inactivation of one or more of such protein kinases. Interestingly, these phenotypes are very reminiscent of those reported due to loss of Aurora B. (Adams et al., 2001; Giet and Glover, 2001). Therefore, we decided to study whether inactivation of Aurora B was likely to contribute to the alterations observed in Cdc37 mutant cells.

RNA interference (RNAi) reveals a functional role of Cdc37 in cytokinesis and cell cycle progression in Drosophila SL2 cells

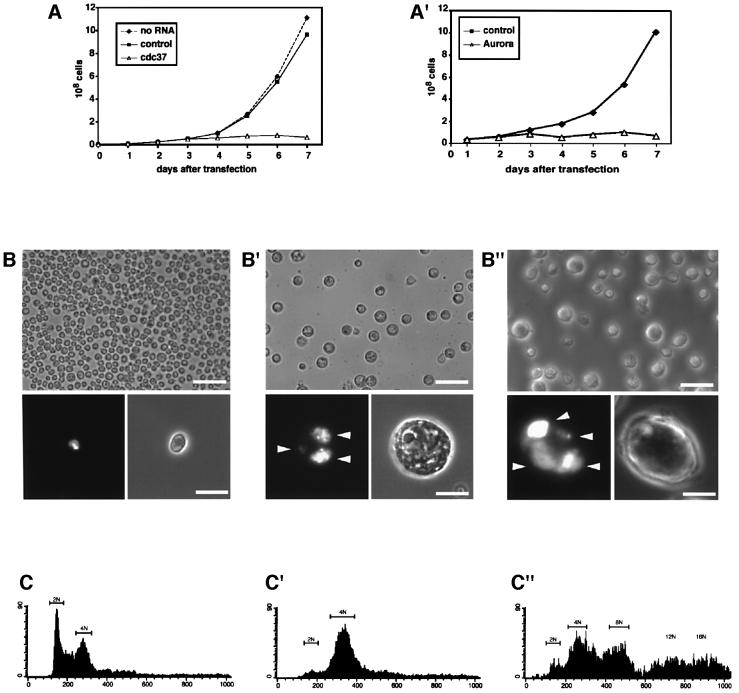

Having shown that Cdc37 is essential for chromosome segregation and cytokinesis in meiosis, we investigated the function of Cdc37 via an independent approach in mitotic cells. To this end, we ablated Cdc37 by RNAi (Clemens et al., 2000) in Drosophila SL2 cells and compared the results with the phenotypes produced by Aurora B RNAi inactivation in these cells. Depletion of Cdc37 inhibited cell proliferation starting 3 days after transfection (Figure 4A), Aurora B depletion inhibited proliferation already after 2 days (Figure 4A′), while control cells [incubated with GFP double stranded (ds) RNA and without dsRNA] followed exponential growth (Figure 4A and A′). Phase contrast and immunofluorescence microscopy analysis revealed that most Cdc37 dsRNA-treated cells (Figure 4B′) had grown abnormally large, i.e. 3–4 times the size of control cells (compare Figure 4B with 4B′) and Aurora B dsRNA–treated cells increased more than 4 times in size (Figure 4B″). Both Cdc37 and Aurora B dsRNA treated cells contained multiple abnormally shaped and unequally sized nuclei (Figure 4B′ and B″, lower panels) indicating cytokinesis failure and problems in chromosome segregation. In addition, these cells also had an increased DNA content. Propidium iodine labelling and subsequent FACS analysis (Figure 4C–C″) revealed that the majority of Cdc37 RNAi-treated cells (75%) had a 4N DNA (Figure 4C′) content, while Aurora B RNAi-treated cells exhibit an even higher degree of ploidy (Figure 4C″). Thus, Cdc37 RNAi cells had accomplished one round of DNA synthesis but had not undergone further rounds of synthesis as detected in the Aurora B dsRNA-treated cells. These results are consistent with cytokinesis failure and problems in chromosome segregation seen in Cdc37 mutant spermatocytes. They are also consistent with the hypothesis that inactivation of Aurora B might be a major contributing factor to the phenotypes brought about by inactivation of Cdc37. Taken together, these results indicate that Cdc37 function is required for cell cycle progression and cytokinesis in meiotic and mitotic cells.

Fig. 4. Cdc37 RNAi leads to cytokinesis failure and blocks cell cycle progression. RNAi with control dsRNA (A, A′, B and C), Cdc37 dsRNA (A′, B′ and C′) and Aurora B dsRNA (A′, B″ and C″) analysed by cell growth (A and A′), morphology and DNA (B–B″) and cell cycle distribution (C–C”). Cdc37 and Aurora B RNAi lead both to abnormally enlarged cells with multiple unequal sized nuclei. (A) The growth of control cells and cells without treatment is exponential, while Cdc37 dsRNA-treated cells do not increase in number 3 days after transfection. (A′) Cells treated with Aurora B dsRNA do not increase in number after 2 days of treatment as compared with control cells. (B) Control cells visualized by phase microscopy display a normal cell size distribution. Lower panel of (B): Examined by fluorescence microscopy, cells have one uniformly shaped nucleus revealed by DAPI staining. (B′) Depletion of Cdc37 by RNAi results after 5 days of treatment in large cells with multiple nuclei (lower panel of B′, see arrowheads) of unequal size, or cells with abnormally deformed DNA. (B″) Depletion of Aurora B by RNAi results after 3 days of treatment in large cells with multiple nuclei (lower panel of B″, see arrowheads) of unequal size or cells with abnormally deformed DNA. (C) FACS analysis of control cells with apparent G1 (2N), S and G2 (4N) DNA content. (C′) FACS analysis reveals a cell cycle distribution with the majority of cells possessing a 4N DNA content much different to controls. The cells with 2N DNA content are greatly reduced in number. (C″) FACS analysis reveals a cell cycle distribution with the majority of cells possessing a 4N and 8N DNA content and higher, much different to controls. The cells with 2N DNA content are greatly reduced in number. Scale bar in (B) and (B′) top panels = 40 µm. Scale bar in (B) and (B′) lower panels = 10 µm.

Cdc37 and Aurora B are part of a molecular complex

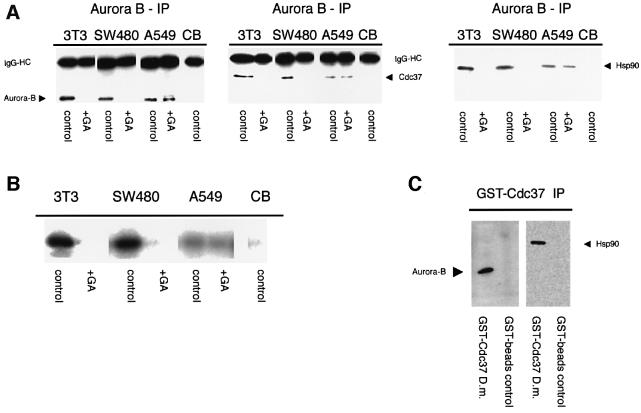

To determine whether Cdc37 and Aurora B are part of a molecular complex, we performed co-immunoprecipitation assays in mitotic extracts from mammalian tissue culture cells and in Drosophila embryonic extracts. We found that Cdc37 co-immunoprecipitates with Aurora B and Hsp90 (Figure 5A) in a number of different cell lines: NIH 3T3, a mouse fibroblast cell line; SW480, a colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line; and A549, a lung carcinoma cell line. This association is absent in cells that were treated with geldanamycin (GA), an inhibitor of the Hsp90/Cdc37 complex (Pearl and Prodromou, 2000), indicating a functional relationship between Cdc37/Hsp90 and Aurora B. Interestingly, Aurora B binds less Cdc37 and Hsp90 in A549 cells when compared with the two other cell lines, and moreover, this interaction seems to be independent of GA treatment (Figure 5A).

Fig. 5. Aurora B, Cdc37 and Hsp90 are part of the same protein complex in human and Drosophila cells but their normal association and kinase activity is disturbed in cancer cells. (A) Cdc37 co-immunoprecipitates with Aurora B from mitotic extracts of NIH 3T3, SW480 and to a lesser extent A549 cells, using the mAb anti-Aurora B. Control beads (CB) exposed to mitotic cell extract carry neither Aurora B nor Cdc37. Hsp90 is also associated with Aurora B in all three different cell lines but not with control beads. There is no Aurora B kinase activity after GA treatment. (B) In vitro kinase assay on histone H3 substrate. The kinase activity from immunoprecipitated Aurora B is strongly reduced when isolated from cells treated with GA. The Aurora B activity in A549 is inherently lower in control or GA-treated cells. CB exposed to mitotic cell extract show no kinase activity. The Cdc37/Aurora B protein complex is conserved between humans and Drosophila. (C) GST–Cdc37 pulls down Aurora B and Hsp90 from Drosophila early embryo extracts, as revealed with an anti-Aurora B rabbit polyclonal antibody and anti-Hsp90 rat mAb.

This raised the question of whether Aurora B in these cells has the same kinase activity as in cells where Aurora B co-immunoprecipitates with higher amounts of Cdc37. We therefore assayed the kinase activity of immunoprecipitated Aurora B on its natural substrate histone H3 in vitro. Kinase activity was high of Aurora B immunoprecipitated from NIH 3T3 cells and SW480 cells but lower from A549 cells (Figure 5B). Moreover, GA treatment of NIH 3T3 cells and SW480 cells resulted in strongly reduced kinase activity. In A549 cells the kinase activity was not affected by the GA treatment. These results confirm that a functional association of the endogenous Aurora B and Cdc37 exists, and that this relationship is disturbed in the A549 cells.

Binding assays in extracts of early Drosophila embryos showed that bacterially expressed GST–Cdc37 pulls down Aurora B and Hsp90 (Figure 5C), suggesting that the association between Aurora B, Hsp90 and Cdc37 is conserved between Drosophila and mammalian cells.

Aurora B stability is maintained by Cdc37 through the Hsp90/Cdc37 complex in wild-type, but not cancer cells

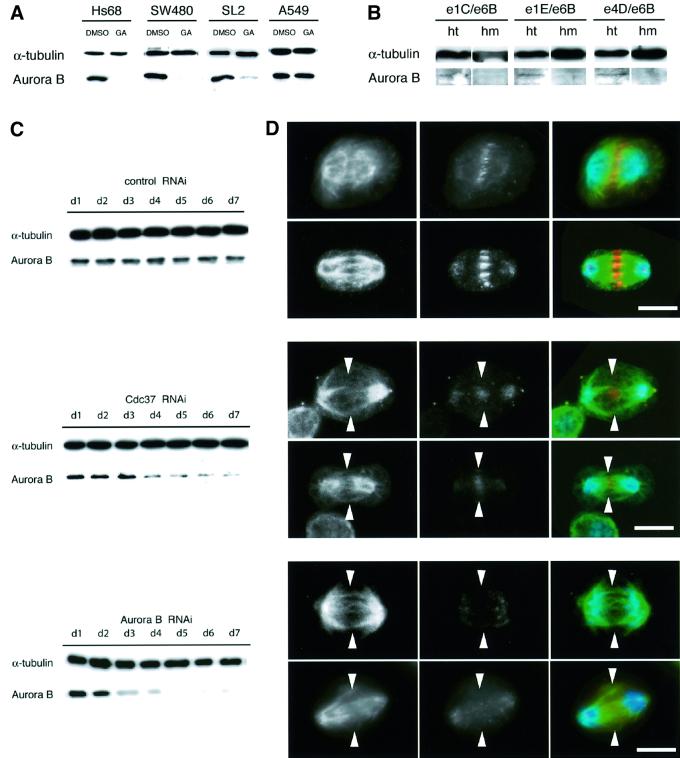

Based on the molecular association between Aurora B and Cdc37, our next approach was to test whether Cdc37 function is required to maintain Aurora B stability. Initially, we examined whether the stability of Aurora B could be dependent upon the function of the Hsp90/Cdc37 complex. We made use of the Hsp90 inhibitor GA; incubation with this drug leads to the destabilization of Hsp90 substrate proteins (Pratt and Toft, 1997). Following drug treatment, Aurora B levels were reduced in the human primary cell line Hs68, the colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line SW480 and the Drosophila cell line SL2, but not in the lung carcinoma A549 cell line (Figure 6A). These results indicate that Aurora B is likely to be a substrate of the Cdc37/Hsp90 complex and that this interaction is conserved between mammals and Drosophila. This is not the case in the A549 cell line, where Aurora B is not degraded, suggesting that a normal interaction between Cdc37/Hsp90 and Aurora B is disturbed, supported also by results that comparatively little Cdc37 co-immunoprecipitated with Aurora B from this cell line.

Fig. 6. Aurora B is stabilized by the Cdc37/Hsp90 complex in primary but not in cancer cells. (A) Treatment of primary (Hs68), human colon adenocarcinoma (SW480) and Drosophila (SL2) cells with the Hsp90 inhibitor GA reduces the levels of the Aurora B kinase, as compared with the control DMSO-treated samples. However, in the human lung carcinoma cell line A549, Aurora B levels remain almost completely unchanged. This indicates that the Hsp90/Cdc37 complex is essential to maintain Aurora B protein levels, while this interaction is disturbed in the A549 cells. α-tubulin is loading control. (B) Drosophila testis prepared from Cdc37 homozygous mutant larvae (hm) and heterozygous control larvae (ht), analyzed by western blotting with an anti-Aurora B antibody. Homozygous mutant testis contain undetectable levels of Aurora B, indicating that functional Cdc37 is required to maintain Aurora B protein levels. The lanes of the mutant (hm) samples are overloaded, as indicated by the tubulin bands, but still no Aurora B can be detected. (C) (Top panel), Aurora B and α-tubulin levels are constant in cells treated with control dsRNA throughout the 7 days of treatment; (middle panel) time course of Cdc37 RNAi in SL2 cells leads to reduced levels of Aurora B after 3 days of treatment, confirming that Cdc37 is required to sustain Aurora B protein levels. α-tubulin is used as loading control; (bottom panel) time course of Aurora B RNAi in SL2 cells leads to reduced levels of Aurora B after 2 days of treatment. Aurora B is not detectable after day 5. (D) Top panel, control cells labelled for α-tubulin (first column, green in overlay), Aurora B (second column, red in overlay) and DNA (blue) show a distinct staining at the central spindle in early and late anaphase; (middle panel), 3–4 days after transfection with Cdc37 dsRNA, the central spindles (first column, arrowheads) have almost completely disappeared and cells have low levels of Aurora B (second column); bottom panel, 2–3 days after transfection with Aurora B dsRNA, the central spindles (first column, arrowheads) have almost completely disappeared and cells have much reduced levels of Aurora B (second column). The phenotype of Cdc37 and Aurora B dsRNA-treated cells both show abnormal organized spindles lacking a dense array of central spindle microtubules. Scale bar in all panels of (D) = 7 µm.

We then investigated the dependency of Aurora B stability on Cdc37 function in Drosophila mutants. We found that testis from third instar larval stages of trans-heteroallelic Cdc37 mutants contained reduced levels of Aurora B when compared with the heterozygous control tissue (Figure 6B). α-tubulin was used as a loading control. The same result was obtained from brain tissue (data not shown). Similar results were also obtained when we compared the Aurora B level in SL2 cells depleted of Cdc37 by RNAi (Figure 6C). These results are in good agreement with the inhibition of cell proliferation that occurs 2 days after transfection with Aurora B RNAi and 3 days after transfection with Cdc37 RNAi.

To understand the consequences of the Aurora B destabilization in the RNAi experiment, we analysed the RNAi and control cells by immunofluorescence microscopy with antibodies against tubulin and Aurora B. We looked at cells 2–4 days after dsRNA treatment, and analysed spindle morphology and the distribution of Aurora B. In control cells, we could detect normally organized spindles (Figure 6D, top panel, first column) with the Aurora B kinase localized to the spindle midzone (Figure 6D, top panel, second column and yellow in superimposition). However, in Cdc37 dsRNA-treated cells and in Aurora B dsRNA-treated cells, severe aberrations in spindle morphology were observed. These include a strongly reduced central spindle and reduced labelling of Aurora B (Figure 6D, middle panel, and see arrowheads in the bottom panel, second column). Especially in the midzone, Aurora B was detected only weakly (Figure 6D, middle panel, and see arrowheads in the bottom panel, second column). In addition to the spindle defects, abnormally segregated DNA and DNA bridges were produced (data not shown).

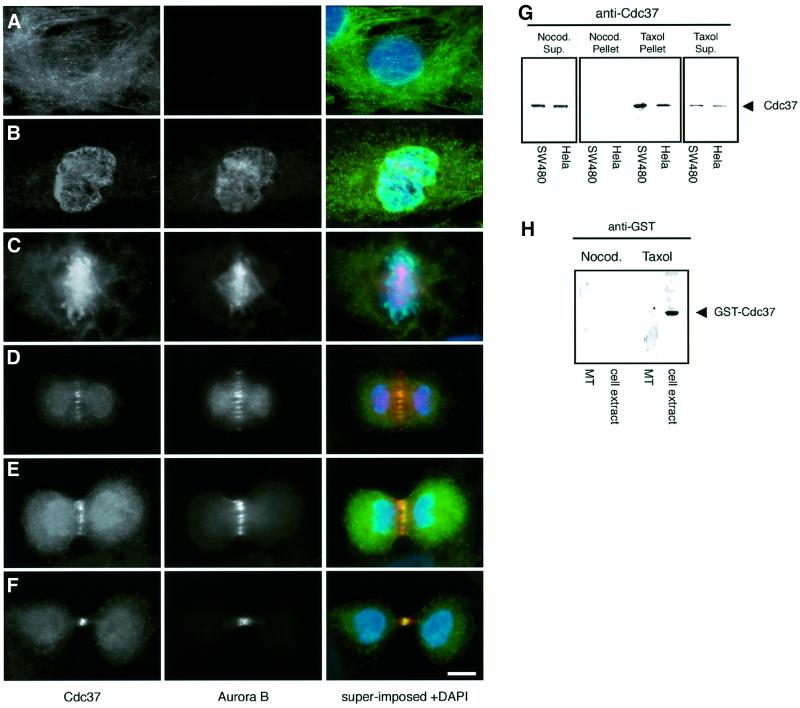

Cdc37 is localized to the spindle and the midbody and associates with microtubules in mitotic cell extracts

A general cytoplasmic and perinuclear localization of Cdc37 has been described previously (Cutforth and Rubin, 1994; Stepanova et al., 1996). Its function in mitosis, however, led us to re-examine its localization throughout the cell cycle. We could confirm the cytoplasmic and perinuclear localization by immunofluorescence microscopy in interphasic mammalian cells (NIH 3T3, SW480 and HeLa) (Figure 7A and B). However, using single labelling with anti-Cdc37 antibodies or double labelling together with an anti-α-tubulin antibody (data not shown), we could detect a distinct labelling in the central spindle and in the midbody. Moreover, Cdc37 co-localizes with Aurora B on the spindle microtubules and midbody (Figure 7D–F). In addition, we performed in vitro microtubule-pelleting assays to test whether this localization of Cdc37 could be due to microtubule binding in mitosis. Extracts from mitotically enriched HeLa and SW480 cells were incubated at 37°C in the presence of taxol to polymerize and stabilize microtubules from endogenous tubulin. Control extracts were incubated with nocodazole to depolymerize microtubules. The microtubules and associated proteins were subsequently pelleted. Only the microtubule-containing pellets carried Cdc37 while the pellets of the nocodazole-treated extracts did not, indicating a specific association of Cdc37 with microtubules (Figure 7G). Some of the Cdc37 protein remained in the supernatant in the taxol-treated samples (Figure 7G) indicating that not all the pool of Cdc37 associates with microtubules. Microtubule pelleting was also carried out using interphase extracts, in which Cdc37 did not pellet with microtubules (data not shown).

Fig. 7. Cdc37 localizes to the spindle and midbody in vivo and binds microtubules in vitro. (A–F) Immunofluorescence of HeLa cells, triple-labelled with antibodies against Cdc37 (green and yellow in super-imposed image), Aurora B (red and yellow, in the superimposed image) and the DNA binding dye DAPI (blue). (A) The anti-Cdc37 antibody labels the cytoplasm in interphase. Aurora B labelling is not detectable. (B) In prophase Cdc37 labelling is cytoplasmic and nuclear. Aurora B labels dotted structures in the nucleus. (C) At metaphase, labelling of Cdc37 is predominant at the metaphase chromosomes, while Aurora B labels chromosomes and spindle structure. (D) The anti-Cdc37 antibody labels the cytoplasm and spindle microtubules in telophase. Aurora B co-localizes in the central spindle area with Cdc37 (yellow superimposition). (E) At the beginning of furrow formation, Cdc37 is present in the cytoplasm and central spindle co-localizing with Aurora B (yellow superimposition). (F) In late telophase, Cdc37 is localized to the central midbody structure together with Aurora B (yellow overlay) and the cytoplasm. (G) Microtubule co-sedimentation assay in mitotic cell extracts from two different cell lines (SW480 and HeLa cells). Cdc37 co-sediments with taxol-stabilized microtubules while control pellets of nocodazole treated samples do not contain Cdc37. A fraction of Cdc37 protein remains in the supernatant of taxol-treated extracts indicating that not the whole pool of Cdc37 is associated with microtubules. Cdc37 remains in the supernatant in colcemid-treated cells. (H) This interaction is likely to be indirect as demonstrated using pure recombinant proteins. GST–Cdc37 binds to microtubules in mitotic cell extracts but not to pure phosphocellulose-purified tubulin. Scale bar = 10 µm.

To further elucidate whether the microtubule association of Cdc37 is direct or indirect, we used pure proteins (Escherichia coli expressed GST–Cdc37 and phosphocellulose purified bovine brain tubulin) in an in vitro binding assay. From these experiments, we concluded that binding of Cdc37 to microtubules requires additional factors (or modifications), as recombinant GST–Cdc37 only binds microtubules in the presence of a mitotic extract (Figure 7H). Hence, the association with the mitotic spindle and its molecular association with the Aurora B kinase are fully consistent with the role of Cdc37 in cytokinesis.

Altogether, our molecular and cytological data established that the function of Cdc37 and the Cdc37/Hsp90 complex are essential in wild-type cells to maintain stability of Aurora B in diverse tissues and cells of Drosophila and humans. Interfering with Cdc37 function leads to lack of a central spindle, aberrant chromosome segregation and cell cycle arrest. Interestingly, the interaction between Aurora B and Cdc37 is defective in certain cancer cells.

Discussion

We have found that loss of Cdc37 function in Drosophila results in a series of abnormal phenotypes that affect chromatin condensation, spindle elongation, chromosome pairing and segregation, organization of the central spindle and cytokinesis. Since Cdc37 is known to target kinases to Hsp90, which are stabilized by this chaperone (Dai et al., 1996; Stepanova et al., 1996; Grammatikakis et al., 1999), it was likely that the observed phenotypes could be the result of the inactivation of one or more of these kinases. One possible candidate is Polo, which is known to be stabilized by Hsp90 (Simizu and Osada, 2000; de Carcer et al., 2001) and whose loss of function gives rise to phenotypes (Sunkel and Glover, 1988; Herrmann et al., 1998) that are reminiscent of some of those brought about by loss of Cdc37. However, the correlation is much more tight with another protein kinase, Aurora B, to the extent that the phenotypes that result from the inactivation of either Cdc37 or Aurora B are almost indistinguishable (Adams et al., 2001; Giet and Glover, 2001; this paper). The main exception is that inactivation of Aurora B does not lead to cell cycle arrest as inactivation of Cdc37 does. Given these close similarities, we investigated whether Aurora B function could require the activity of the Hsp90/Cdc37 complex. We indeed found this to be the case; inactivation by different methods of either Cdc37 or Hsp90 in flies and mammalian culture cells resulted in a very significant reduction of the levels of Aurora B. In addition, we were able to show that Cdc37, Aurora B and Hsp90 co-immunoprecipitate. Taken altogether, these results show that the Hsp90/Cdc37 complex modulates the function of Aurora B, and strongly suggest that the phenotypes brought about by the loss of Cdc37 function can be largely accounted for by the inactivation of this kinase. However, the partial contribution of the loss of function of Polo and other as yet unidentified protein kinases cannot be ruled out.

It seems likely that the complexity of the abnormal phenotypes brought about by the loss of Cdc37 may reflect a cascade of events in which errors at one particular stage lead to errors in subsequent stages. In fact, most of the abnormal phenotypes that we observe could in principle be traced back to two original ones: impaired chromatin structure and abnormal spindles. One of the essential factors that contribute to the fidelity of chromosome segregation during meiosis is the controlled release of cohesion between homologue chromosomes and sister chromatids. At the onset of anaphase I, cohesion is released along the arms but maintained at the centromere until anaphase II, thus allowing the bipolar orientation of the sister chromatids in the second meiotic division (Dej and Orr-Weaver, 2000). In Cdc37 mutant spermatocytes, cohesion along the arms is lost during late prometaphase I, coinciding with the premature and asynchronous splitting of the homologue chromosomes. This, in turn, results in some chromosomes acquiring an amphitelic orientation (with both sister chromatids attached to each pole) during meiosis I, which leads to the segregation of the chromatids and thus to aneuploidy. Therefore, aneuploid gametes, aberrant chromosome orientation and precocious chromosome separation may be accounted for by impaired chromosome cohesion (Goldstein, 1980; Dej and Orr-Weaver, 2000). Moreover, impaired cohesion could be tightly related to the abnormal chromosome condensation displayed by Cdc37 mutant spermatocytes.

The loss of function of Aurora B also leads to aberrant chromosome orientation and segregation (Kaitna et al., 2002; Kallio et al., 2002; Rogers et al., 2002; Tanaka et al., 2002). Abrogation of Aurora B function leads also to abnormal chromosome condensation and it has been proposed that this could physically interfere with normal chromosome movement in the spindle and result in aneuploidy (Adams et al., 2001; Giet and Glover, 2001).

The other major phenotypes brought about by loss of Cdc37 are the lack of a central spindle and cytokinesis failure. Here too, it is likely that the latter is a consequence of the former, as the interdependency between the assembly of the central spindle and the contractile ring in Drosophila is well established (Giansanti et al., 1998). These two phenotypes have also been observed following the loss of Aurora B function.

The interaction between Aurora B and Cdc37 that we have observed in flies and primary human cells is disturbed in the lung carcinoma A549 and other cancer cells (data not shown). In these cells, GA treatment does not result in the inactivation of this kinase that still co-immunoprecipitates with Cdc37. How these cells can escape the effect of GA we do not know. In the case of Polo, whose stability in these cells has also been shown to be insensitive to GA, it has been proposed that these cells contain a mutant allele of this gene that does not depend upon the Hsp90 complex for its stability (Simizu and Osada, 2000). Interestingly, substrates of Cdc37 have been implicated in tumorigenesis and are either overexpressed, amplified or mutated in somatic cancer cells. For example, members of the Aurora kinase family are overexpressed in tumour types, such as human colorectal, breast, prostate and ovarian cancer (Bischoff et al., 1998; Tatsuka et al., 1998; Zhou et al., 1998). Moreover, Cdc37 itself is upregulated in some human prostatic tumours, neoplasias and pre-malignant lesions and, when overexpressed in mice, can induce hyperplasia and dysplasia (Stepanova et al., 2000a,b). Our results provide evidence that functional Cdc37 is required for the fidelity of chromosome segregation and cell division, and show that a shift in the balance between Cdc37 and the cell cycle machinery lead to abnormalities that ultimately could result in genomic instability. Future studies will need to show whether mutations in chaperones or their substrates, i.e. mutations that are relevant for chaperone interaction, are critical for the early events that lead to oncogenic transformation.

Materials and methods

Fly stocks

The four mutant alleles of Cdc37 used in this study (Cutforth and Rubin, 1994) were: Cdc37e1C, Cdc37e1E, Cdc37e4D and Cdc37e6B. Except for Cdc37e6B these are early lethal mutations, but can reach the stage of third instar larvae as trans-heteroallelic combinations with Cdce6B. The trans-heterozygous combinations hsp83582/hsp839JI and hsp83582/hsp8313F3 of Hsp90 mutant alleles (van der Straten et al., 1997) that allow for larval development were analysed by testis squash techniques with phase microscopy.

Testis squash and live video imaging of spermatocytes

Testis squashes were performed according to Gonzalez and Glover (1993). Live video imaging was performed as described previously by Rebollo and Gonzalez (2000).

Tissue culture cell lines

The human cell lines SW480, SW948 and A549 were obtained from the German tissue culture collection (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany), the human newborn foreskin primary cell line Hs68 was obtained from the ECACC (Salisbury, UK).

Immunofluorescence microscopy and image processing

Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed as described previously by Lange and Gull (1995) with the difference that SL2 cells were spun down onto poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips in 24-well plates prior to processing for immunofluorescence microscopy. Images were either acquired by laser scanning confocal microscopy using the Leica TCS SP-confocal system or with a 12 bit Hamamatsu Orca C4742-95 CCD camera (Hamamatsu, München, Germany) and the OpenLab software (Improvision, Heidelberg, Germany).

Flow cytometry

DNA content of Drosophila SL2 cells was measured after propidium iodide staining using standard methods (Robinson et al., 1999) with a FACS-scan flow cytometer from Becton-Dickinson. Excitation was at 488 nm and fluorescence emitted was collected using a 585 nm/26 bandpass filter.

SL2 cell culture and RNA interference

SL2 cells were propagated at 25°C in Schneider’s Drosophila medium. dsRNAi was performed essentially as described previously by Clemens et al. (2000). SL2 cells were washed twice in serum-free medium, resuspended in serum-free medium and dsRNA was added. After 1.5 h, an equal amount of medium containing 20% FCS was supplemented. GFP–dsRNA was used as a control. Cdc37 dsRNA and GFP–dsRNA both correspond to the first 650 bp of the coding region. Aurora B dsRNA corresponds to the 650 bp of exon 2. dsRNA-treated cells were counted and then assayed by immunofluorescence microscopy, phase microscopy, FACS analysis and western blotting. Components were purchased from Life Technologies.

Antibodies

We used the following antibodies: anti-α-tubulin DM1A and anti-γ-tubulin (Sigma, München, Germany), anti-Cdc37 mouse mAb, clone C1 (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany), anti-Cdc37 mouse mAb clone 15m, anti-AIM-1 mAb (BD Transduction Laboratories, Heidelberg, Germany) and anti-Aurora B rabbit polyclonal antibody (a gift from Drs Giet and Glover).

Microtubule pelleting assay

Mammalian cell lines were grown to ∼80% density and extracted in lysis buffer (1% Triton, 25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonident P-40, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM ortho-vanadate and proteinase inhibitor mix). Per assay, 500 µg of protein were used. Microtubule pelleting assays were performed according to Ploubidou et al. (2000). Samples were spun through a 15% sucrose cushion. Resulting pellets were resuspended in equal amounts of SDS–PAGE sample buffer and analysed by western blotting techniques.

Cdc37 protein expression

The Drosophila Cdc37 gene was isolated by PCR from a cDNA library (Brown and Kafatos, 1988), subcloned into the pGEX-6-P2 plasmid (Pharmacia) and expressed as a GST fusion protein in Xl-l-Blue cells from Stratagene (Amsterdam, Netherlands) at 37°C in liquid cultures. Resuspended cell pellets were lysed in phosphate buffer (0.05 M PO4Na, 0.3 M NaCl, 0.5 % Triton X-100 pH 7.5) supplemented with a proteinase inhibitor mix, sonicated and batch purified using glutathione–Sepharose 4 fast flow according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Pharmacia).

Immunoprecipitation and kinase assay

Immunoprecipitation was performed essentially as described previously by Grammatikakis et al. (1999). SW480, NIH 3T3 and A549 cells were enriched in mitosis by incubation for 8 h with taxol and nocodazole, then lysed and a post-nuclear high-speed extract was made. This extract was incubated with the anti-Aurora B antibody for 1 h at 4°C and then incubated for an additional 1 h with protein G beads. Beads were pelleted, washed four times and analysed after western blotting by probing with anti-Cdc37 and anti-Aim-1 antibodies. In each immunoprecipitation 2 mg of protein was used. Drosophila embryo extract was prepared as described previously by Moritz et al. (1995), supplemented with 2 mM sodium ortho-vanadate and centrifuged at 210 000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The GST fusion protein pull-down was performed by adding 2 µg of purified GST–Cdc37 fusion protein to 5 mg of high-speed supernatant of Drosophila embryo extract, incubated for 1 h at 4°C followed by addition of 30 µl of glutathione–Sepharose 4 fast-flow beads (Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany), and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. Then beads were washed four times and processed for western blotting analysis.

For the kinase assay, NIH 3T3, SW480 and A549 cells were mitotically arrested and processed for immunoprecipitation with the anti-AIM-1 antibody as described previously. Equal amounts of beads were washed first three times in immunoprecipitation buffer and then once in high salt buffer to remove non-specific kinase activity. Each sample was incubated with 6 µg of purified histone H3 for 20 min at 37°C and processed according to conditions described previously (Karaiskou et al., 2001).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to E.Hafen and G.Rubin for mutant fly stocks, to R.Giet and D.Glover for the anti-Aurora B antibody, to A.Atzberger for help with the flow cytometer, to E.Perdiguero and other members of the Nebreda group for help with the kinase assays and the kind gift of histone H3, to S.Llamazares who provided the GFP–α-tubulin-expressing flies, and to all members of the González laboratory and A.Ploubidou for support and discussions. The TCS-SP confocal microscope used here was kindly provided by Leica Microsystems. B.M.H.L. was supported by a research grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). Our laboratory is supported by grants from the EU and the Ramon Areces Foundation.

References

- Adams R.R., Maiato,H., Earnshaw,W.C. and Carmena,M. (2001) Essential roles of Drosophila inner centromere protein (INCENP) and Aurora B in histone H3 phosphorylation, metaphase chromosome alignment, kinetochore disjunction, and chromosome segregation. J. Cell Biol., 153, 865–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff J.R. et al. (1998) A homologue of Drosophila Aurora kinase is oncogenic and amplified in human colorectal cancers. EMBO J., 17, 3052–3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N.H., and Kafatos,F.C. (1988) Functional cDNA libraries from Drosophila embryos. J. Mol. Biol., 203, 425–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens J.C., Worby,C.A., Simonson-Leff,N., Muda,M., Maehama,T., Hemmings,B.A. and Dixon,J.E. (2000) Use of double-stranded RNA interference in Drosophila cell lines to dissect signal transduction pathways. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA., 97, 6499–6503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutforth T. and Rubin,G.M. (1994) Mutations in Hsp83 and cdc37 impair signaling by the sevenless receptor tyrosine kinase in Drosophila. Cell, 77, 1027–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai K., Kobayashi,R. and Beach,D. (1996) Physical interaction of mammalian Cdc37 with CDK4. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 22030–22034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dej K.J. and Orr-Weaver,T.L. (2000) Separation anxiety at the centromere. Trends Cell Biol., 10, 392–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey B., Lightbody,J.J. and Boschelli,F. (1996) Cdc37 is required for p60v-src activity in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell, 7, 1405–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cárcer G., do Carmo Avides,M., Lallena,M.J., Glover,D.M. and Gonzalez,C. (2001) Requirement of Hsp90 for centrosomal function reflects its regulation of Polo kinase stability. EMBO J., 20, 2878–2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller M.T. (1993) Spermatogenesis. In Bate,M. and Arias,A.M. (eds), The Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Vol. I. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. pp. 71–147.

- Gerber M.R., Farrell,A., Deshaies,R.J., Herskowitz,I. and Morgan,D.O. (1995) Cdc37 is required for association of the protein kinase Cdc28 with G1 and mitotic cyclins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 4651–4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giansanti M.G., Bonaccorsi,S., Williams,B., Williams,E.V., Santolamazza,C., Goldberg,M.L. and Gatti,M. (1998) Cooperative interactions between the central spindle and the contractile ring during Drosophila cytokinesis. Genes Dev., 12, 396–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giet R. and Glover,D.M. (2001) Drosophila Aurora B kinase is required for histone H3 phosphorylation and condensin recruitment during chromosome condensation and to organize the central spindle during cytokinesis J. Cell Biol., 152, 669–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotzer M. (2001) Animal cell cytokinesis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol., 17, 351–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover C.V. III, (1998) On the physiological role of casein kinase II in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol., 59, 95–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein L.S. (1980) Mechanisms of chromosome orientation revealed by two meiotic mutants in Drosophila melanogaster. Chromosoma, 78, 79–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C. and Glover,D.M. (1993) Techniques for studying mitosis in Drosophila. In Fantes,P. and Brook,R. (eds), The cell cycle: Practical Approach. IRL Press at Oxford University Press, pp. 143–175.

- Gonzalez C., Casal,J. and Ripoll,P. (1989) Relationship between chromosome content and nuclear diameter in early spermatids of Drosophila melanogaster. Genet. Res., 54, 205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grammatikakis N., Lin,J.H., Grammatikakis,A., Tsichlis,P.N. and Cochran,B.H. (1999) p50(cdc37) acting in concert with Hsp90 is required for Raf-1 function. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 1661–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna D.E., Rethinaswamy,A. and Glover,C.V. (1995) Casein kinase II is required for cell cycle progression during G1 and G2/M in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 25905–25914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann S., Amorim,I., Sunkel,C.E. (1998) The POLO kinase is required at multiple stages during spermatogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Chromosoma, 107, 440–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Grammatikakis,N. and Toole,B.P. (1998) Organization of the chick Cdc37 gene. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 3598–3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T. and Poon,R.Y.C. (1997) Cdc37: a protein kinase chaperon. Trends Cell Biol., 7, 157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaitna S., Mendoza,M., Jantsch-Plunger,V. and Glotzer,M. (2000) Nucleotide Incenp and an Aurora-like kinase form a complex essential for chromosome segregation and efficient completion of cytokinesis. Curr. Biol., 10, 1172–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaitna S., Pasierbek,P., Jantsch,M., Loidl,J. and Glotzer,M. (2002) The aurora B kinase AIR-2 regulates kinetochores during mitosis and is required for separation of homologous chromosomes during meiosis. Curr. Biol., 12, 798–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallio M.J., McCleland,M.L., Stukenberg,P.T. and Gorbsky,G.J. (2002) Inhibition of aurora B kinase blocks chromosome segregation, overrides the spindle checkpoint, and perturbs microtubule dynamics in mitosis. Curr. Biol., 12, 900–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaiskou A., Perez,L.H., Ferby,I., Ozon,R., Jessus,C. and Nebreda,A.R. (2001) Differential regulation of Cdc2 and Cdk2 by RINGO and cyclins. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 36028–36034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y., Rutherford,S.L., Miyata,Y., Yahara,I., Freeman,B.C., Yue,L., Morimoto,R.I. and Lindquist,S. (1997) Cdc37 is a molecular chaperone with specific functions in signal transduction. Genes Dev., 11, 1775–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange B.M.H. and Gull,K. (1995) A molecular marker for centriole maturation in the mammalian cell cycle. J. Cell Biol., 130, 919–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz M., Braunfeld,M.B., Fung,J.C., Sedat,J.W., Alberts,B.M. and Agard,D.A. (1995) Three-dimensional structural characterization of centrosomes from early Drosophila embryos. J. Cell Biol., 130, 1149–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg E. (2001) Mitotic kinases as regulators of cell division and its checkpoints. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol., 2, 21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl L.H. and Prodromou,C. (2000) Structure and in vivo function of Hsp90. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10, 46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew G., Wiegand,H., Vanden Heuvel,J., Mitchell,C. and Singh.S. (1997) A 50 kiloDalton protein associated with Raf and pp60v-src protein kinase is a mammalian homolog of the cell cycle control protein Cdc37. Biochemistry, 36, 3600–3607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines J. (1999) Four-dimensional control of the cell cycle. Nat. Cell Biol., 1, E73–E79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploubidou A., Moreau,V., Ashman,K., Reckmann,I., Gonzalez,C. and Way,M. (2000) Vaccinia virus infection disrupts microtubule organization and centrosome function. EMBO J., 19, 3932–3944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt W.B. and Toft,D.O. (1997) Steroid receptor interactions with heat shock protein and immunophilin chaperones. Endocr. Rev., 18, 306–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebollo E. and González,C. (2000) Visualizing the spindle checkpoint in Drosophila spermatocytes. EMBO rep., 1, 65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed S.I. (1980) The selection of S.cerevisiae mutants defective in the start event of cell division. Genetics, 95, 561–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J.P., Darzynkiewicz,Z., Dean,P., Orfao,A., Rabinovitch,P., Stewart,C., Tanke,H. and Wheeless,L. (eds) (1999) Current Protocols in Flow Cytometry, Vol. I. Wiley, New York, NY.

- Rogers E., Bishop,J.D., Waddle,J.A., Schumacher,J.M. and Lin,R. (2002) The aurora kinase AIR-2 functions in the release of chromosome cohesion in Caenorhabditis elegans meiosis. J. Cell Biol., 157, 219–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos U.P. (1976) Light and electron microscopy of rat kangaroo cells in mitosis. III. Patterns of chromosome behavior during prometaphase. Chromosoma, 54, 363–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutz A.R., Giddings,T.H.,Jr, Steiner,E. and Winey,M. (1997) The yeast Cdc37 gene interacts with MPS1 and is required for proper execution of spindle pole body duplication. J. Cell Biol., 136, 969–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein A.M., Grammatikakis,N., Cochran,B.H., Chinkers,M. and Pratt,W.B. (1998) p50(cdc37) binds directly to the catalytic domain of Raf as well as to a site on hsp90 that is topologically adjacent to the tetratricopeptide repeat binding site. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 20090–20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simizu S. and Osada,H. (2000) Mutations in the Plk gene lead to instability of Plk protein in human tumour cell lines. Nat. Cell Biol., 2, 852–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova L., Leng,X., Parker,S.B. and Harper,J.W. (1996) Mammalian p50Cdc37 is a protein kinase-targeting subunit of Hsp90 that binds and stabilizes Cdk4. Genes Dev., 10, 1491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova L., Leng,X. and Harper,J.W. (1997) Analysis of mammalian Cdc37, a protein kinase targeting subunit of heat shock protein 90. Methods Enzymol., 283, 220–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova L., Finegold,M., DeMayo,F., Schmidt,E.V. and Harper,J.W. (2000a) The oncoprotein kinase chaperone Cdc37 functions as an oncogene in mice and collaborates with both c-myc and cyclin D1 in transformation of multiple tissues. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 4462–4473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova L., Yang,G., DeMayo,F., Wheeler,T.M., Finegold,M., Thompson,T.C. and Harper,J.W. (2000b) Induction of human Cdc37 in prostate cancer correlates with the ability of targeted Cdc37 expression to promote prostatic hyperplasia. Oncogene, 19, 2186–2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunkel C.E. and Glover,D.M. (1988) polo, a mitotic mutant of Drosophila displaying abnormal spindle poles. J. Cell Sci., 89, 25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T.U., Rachidi,N., Janke,C., Pereira,G., Galova,M., Schiebel,E., Stark,M.J. and Nasmyth,K. (2002) Evidence that the Ipl1–Sli15 (Aurora kinase-INCENP) complex promotes chromosome bi-orientation by altering kinetochore-spindle pole connections. Cell, 108, 317–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuka M., Katayama,H., Ota,T., Tanaka,T., Odashima,S., Suzuki,F. and Terada,Y. (1998) Multinuclearity and increased ploidy caused by overexpression of the Aurora- and Ipl1-like midbody-associated protein mitotic kinase in human cancer cells. Cancer Res., 58, 4811–4816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada Y., Tatsuka,M., Suzuki,F., Yasuda,Y., Fujita,S. and Otsu,M. (1998) AIM-1: a mammalian midbody-associated protein required for cytokinesis. EMBO J., 17, 667–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Straten A., Rommel,C., Dickson,B. and Hafen,E. (1997) The heat shock protein 83 (Hsp83) is required for Raf-mediated signalling in Drosophila.EMBO J., 16, 1961–1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Kuang,J., Zhong,L., Kuo,W.L., Gray,J.W., Sahin,A., Brinkley,B.R. and Sen,S. (1998) Tumour amplified kinase STK15/BTAK induces centrosome amplification, aneuploidy and transformation. Nat. Genet., 20, 189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]