Abstract

The Sho1 adaptor protein is an important element of one of the two upstream branches of the high-osmolarity glycerol (HOG) mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a signal transduction cascade involved in adaptation to stress. In the present work, we describe its role in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans by the construction of mutants altered in this gene. We report here that sho1 mutants are sensitive to oxidative stress but that Sho1 has a minor role in the transmission of the phosphorylation signal to the Hog1 MAP kinase in response to oxidative stress, which mainly occurs through a putative Sln1-Ssk1 branch of the HOG pathway. Genetic analysis revealed that double ssk1 sho1 mutants were still able to grow on high-osmolarity media and activate Hog1 in response to this stress, indicating the existence of alternative inputs of the pathway. We also demonstrate that the Cek1 MAP kinase is constitutively active in hog1 and ssk1 mutants, a phenotypic trait that correlates with their resistance to the cell wall inhibitor Congo red, and that Sho1 is essential for the activation of the Cek1 MAP kinase under different conditions that require active cell growth and/or cell wall remodeling, such as the resumption of growth upon exit from the stationary phase. sho1 mutants are also sensitive to certain cell wall interfering compounds (Congo red, calcofluor white), presenting an altered cell wall structure (as shown by the ability to aggregate), and are defective in morphogenesis on different media, such as SLAD and Spider, that stimulate hyphal growth. These results reveal a role for the Sho1 protein in linking oxidative stress, cell wall biogenesis, and morphogenesis in this important human fungal pathogen.

Adaptation to stress is an essential mechanism for every living cell to ensure its survival under nonoptimal conditions. The response against osmotic stress in yeast is, in part, mediated by the high-osmolarity glycerol (HOG) pathway, a mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascade that is triggered in response to a high concentration of solutes. This leads to the sequential phosphorylation of different proteins resulting in the activation of downstream transcription factors that finally generates the appropriate adaptive response. In the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the HOG pathway is responsible for increasing the intracellular compatible solute glycerol that counteracts external osmolarity, therefore preventing dehydration of the cell (8). In this organism, the route is composed of at least two branches that act as inputs of the cascade (6, 29, 31, 67). The first one relies on Sln1, a protein first identified as the suppressor of the lethal phenotypes associated with the N-end rule pathway (64) and a member of a two-component system. Sln1 is a transmembrane sensor whose basal activation under isosmotic conditions (by means of an intrinsic histidine kinase activity) triggers the sequential phosphorylation of Ypd1 and Ssk1 (46, 69, 78) as well as the SKN7 protein (46). Activated Ssk1 blocks further activation of the cascade and is a substrate for Ubc7-mediated proteasome degradation (73). Under hyperosmotic conditions, however, unphosphorylated Ssk1 is accumulated, and interaction with Ssk2/Ssk22 activates its kinase activity, resulting in phosphorylation of the Pbs2 (MAP kinase kinase) (7), which in turn phosphorylates the Hog1 MAP kinase (8). A second branch of the pathway requires the activation of the Ste11 kinase kinase kinase, which involves the Ste11-interacting protein Ste50, the Ste20 p21-activated kinase, and the small GTPase Cdc42 in addition to the transmembrane Sho1 adaptor (33, 62, 67, 68, 70, 71, 82; see references 20 and 31 for recent reviews). Activated Ste11 is able to phosphorylate the Pbs2 MAP kinase kinase (7), which in turns phosphorylates Hog1. Sho1 is apparently responsible for attaching this kinase complex to regions more vulnerable to osmotic stress, such as the shmoo of mating cells or the regions of bud emergence; this task is accomplished through the SH3 domain of Sho1 and a proline-rich region of Pbs2 (49, 50, 85). Both inputs are different in terms of timing and threshold required to trigger the pathway, a result with physiological significance (49). Sho1 plays a pivotal role in signal transduction, acting as a scaffold protein that interacts with Ste11 (84), Msb2 (17), and Fus1 (59), in determining the specificity and magnitude of the response.

Given the role of signal transduction pathways as sensing mechanisms, their study is important in fungal pathogens to understand their adaptation to the host and, therefore, the molecular mechanisms of fungal pathogenicity. Candida albicans is the most prevalent cause of fungal infections, mainly because of its commensal role in the intestinal and vaginal tracts; it is, therefore, a well-established model of a fungal pathogen for which different genetic tools have been recently developed (19, 57). In this organism, some elements of the HOG pathway have been recently identified. The Hog1 MAP kinase was cloned by its functional homology to S. cerevisiae Hog1 and was shown to play a role in osmotic stress and morphogenesis (2). The enhanced susceptibility to oxidative stress of hog1 mutants, which could partially account for its reduced virulence in a mouse model of systemic infection (2), can be explained by the oxidative stress-dependent activation of the Hog1 kinase (3). Other putative elements of the pathway have been isolated recently, such as SLN1 (bearing a histidine kinase and a receiver domain) (54), YPD1 (11), and SSK1 (bearing a receiver domain) (12). Interestingly, other histidine kinases have been described in this organism, NIK1 (1, 54) and CHK1 (10), but their role in signal transduction pathways is uncertain. C. albicans ssk1 mutants also display a set of morphological alterations, such as their reduced ability to form hyphae on serum (phenotypes not suppressed by Hog1 overexpression) (1, 12) and enhanced killing by human polymorphonuclear neutrophils (23). They do not show, however, striking osmosis-dependent phenotypes, indicating either an apparent lack of relationship to the HOG pathway or the existence of an alternative input of the pathway in this organism. Two other signal transduction pathways have been characterized from this organism. Mkc1, the homolog of the S. cerevisiae Slt2/Mpk1 MAP kinase, plays a role in the cell integrity pathway and is involved in cell wall formation (21, 55, 56). In addition, another MAP kinase pathway involved in morphogenesis, hypha formation, and virulence has been characterized (80) through the isolation of the Cek1 MAP kinase (81), the Hst7 MAP kinase kinase (43), and other upstream and downstream elements (15, 75, 79). Deletion of CEK1 results in hypha formation defects and reduced virulence in certain animal models (16).

In this work we isolated and characterized the Sho1 protein in C. albicans, demonstrating its role in the oxidative stress response and in the activation of the Cek1 MAP kinase in this organism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

Yeast and bacterial strains are listed in Table 1. For clarity, unless otherwise stated, sho1, hog1, ssk1, sln1, nik1, hk1, hst7, cek1, and cst20 and the double mutants sho1 hog1 and sho1 ssk1 indicate the homozygous strains (deletions of both alleles, sho1/sho1, etc., in a Ura+ background, with the only exception being the cst20 mutant, where the Ura− background is used). This abbreviated nomenclature for strains in the figures has been included in Table 1 for clarity. The wild-type strain RM100 was used as a control, since it is a Ura+ His− (his1Δ) strain derived from CAI4 but otherwise identical to SC5214 and to the rest of the mutants (3). C. albicans was transformed using the lithium acetate method (38) for gene manipulation.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Microorganism | Strain | Genotype | Nomenclature in this study | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | DH5α F′ | K-12 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 supE44 thi-1 recA1 endA1 hsdR17 gyrA relA1 φ80lacZΔM15 F′ | 30 | |

| S. cerevisiae | FP50 | MATaura3 leu2 his3 ssk2::LEU2 ssk22::LEU2 ste11::HIS3 | ssk2 ssk22 ste11 | F. Posas |

| S. cerevisiae | MY007 | MATaura3 leu2 his3 ssk2::LEU2 ssk22::LEU2 sho1::HIS3 | ssk2 ssk22 sho1 | F. Posas |

| C. albicans | SC5314 | 27 | ||

| C. albicans | RM100 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG | wt | 58 |

| C. albicans | RM1000 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG | 58 | |

| C. albicans | CNC13 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG hog1::hisG-URA3-hisG/hog1::hisG | hog1 | 72 |

| C. albicans | CNC15 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG hog1::hisG/hog1::hisG | 4 | |

| C. albicans | REP1 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG SHO1/sho1::hisG-URA3-hisG | This work | |

| C. albicans | REP2 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG SHO1/sho1::hisG | This work | |

| C. albicans | REP3 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG sho1::hisG/sho1::hisG-URA3-hisG | sho1 | This work |

| C. albicans | REP4 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG sho1::hisG/sho1::hisG | This work | |

| C. albicans | REP5 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG Δsho1::SHO1-GFP | sho1::SHO1-GFP | This work |

| C. albicans | REP6 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG hog1::hisG/hog1::hisG SHO1/sho1::hisG-URA3-hisG | This work | |

| C. albicans | REP7 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG hog1::hisG/hog1::hisG SHO1/sho1::hisG | This work | |

| C. albicans | REP8 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG hog1::hisG/hog1::hisG sho1/sho1::hisG-URA3-hisG | sho1 hog1 | This work |

| C. albicans | REP9 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG hog1::hisG/hog1::hisG sho1/sho1::hisG | This work | |

| C. albicans | REP10 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG ssk1::hisG/ssk1::hisG SHO1/sho1::hisG-URA3-hisG | This work | |

| C. albicans | REP11 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG ssk1::hisG/ssk1::hisG SHO1/sho1::hisG | This work | |

| C. albicans | REP12 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG ssk1::hisG/ssk1::hisG sho1::hisG-URA3-hisG/sho1::hisG | sho1 ssk1 | This work |

| C. albicans | REP13 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG ssk1::hisG/ssk1::hisG sho1::hisG/sho1::hisG | This work | |

| C. albicans | CSSK21 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 ssk1::hisG/ssk1::hisG-URA3-hisG | ssk1 | 12 |

| C. albicans | CSSK21U | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 ssk1::hisG/ssk1::hisG | This work | |

| C. albicans | S | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 sln1::hisG/sln1::hisG-URA3-hisG | sln1 | 54 |

| C. albicans | N | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 nik1/nik1::hisG-URA3-hisG | nik1 | 83 |

| C. albicans | H | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 hk1/hk1::hisG-URA3-hisG | hk1 | 83 |

| C. albicans | SN | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 sln1/sln1 NIK1/nik1::hisG-URA3-hisG | sln1 NIK1/nik1 | 83 |

| C. albicans | SH | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 sln1/sln1 hk1/hk1::hisG-URA3-hisG | sln1 hk1 | 83 |

| C. albicans | NH | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 nik1/nik1 hk1/hk1::hisG-URA3-hisG | nik1 hk1 | 83 |

| C. albicans | CK43B-16 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 cek1::hisG/cek1::hisG-URA3-hisG | cek1 | 16 |

| C. albicans | CDH10 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 hst7::hisG/hst7::hisG-URA3-hisG | hst7 | 43 |

| C. albicans | CDH25 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 cst20/cst20::hisG | cst20 | 43 |

Yeast strains were grown at 37°C in YEPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) and SD minimal medium (2% glucose, 0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids) with the appropriate nutritional requirements at 50 μg/ml (final concentration) for auxotrophs. The morphology of cells under different growth conditions was tested using YEPD medium, Spider medium (1% mannitol, 1% nutrient broth, 0.2% K2HPO4, and 1.35% agar) (48), or SLADH medium (28).

Drug susceptibility assays.

Drop tests were performed by spotting 105, 104, 103, and 102 cells onto YEPD plates supplemented with sodium chloride, sorbitol, H2O2, menadione, Congo red, and calcofluor white at the indicated concentrations. Plates were incubated 24 h at 37°C and scanned. Diffusion test assays were carried out by spreading 2 × 106 cells on a solid medium plate (YEPD) and then adding a dried disk previously loaded with 10 μl of H2O2 (33%) or menadione (1 M); the plates were then incubated 24 h at 37°C before measurement of the halos.

Isolation of Candida albicans SHO1.

To isolate the Candida albicans SHO1 gene, we used S. cerevisiae MY007 (ssk2 ssk22 sho1) and FP50 (ssk2 ssk22 ste11) as genetic host strains (Table 1). In these mutants, both inputs of the HOG pathway are blocked, resulting in an osmosensitive phenotype and, therefore, an inability to grow on solid medium containing a high concentration of solutes. These strains were transformed with a C. albicans episomic library constructed in the YEp352 vector (56), and clones able to grow on minimal medium supplemented with 0.9 M sodium chloride were isolated upon replication from minimal medium transformation plates. Seven clones (c18, c35, c52, c56, c58, c66, and c88) were selected from among more than 75,000 independent clones from the MY007 strain, and in all of them, the osmoresistant phenotype was shown to be plasmid linked by standard complementation analyses. Sequence analysis revealed that clone c58 hybridized to contigs 4-2351 and 4-1937 from the Stanford C. albicans Genome Database Assembly 4 and contained regions overlapping those of clones c35 and c88. The remaining clones are described elsewhere. Since the C. albicans homolog to the S. cerevisiae SHO1 gene was found in the three contigs, it was presumed to be the functional genetic element and named C. albicans SHO1; this was later confirmed by the failure to complement the MY007 strain with distinct genetic constructions in which the putative SHO1 open reading frame (ORF) was truncated (data not shown).

Molecular biology procedures and plasmid constructions.

The oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 2. Standard molecular biology procedures were used for all genetic constructions (5). For the disruption of the SHO1 gene, the oligonucleotides SHOUP1and SHOLP2 were employed to amplify a 0.83-kbp 5′ region flanking the ORF and subcloned in pGEMT. Similarly, oligonucleotides SHO3N and SHO4N were used to amplify a 0.63-kbp 3′ flanking region of the ORF from C. albicans strain SC5314 and subcloned in pGEMT. The 5′ and 3′ regions were excised from these constructions using the combination of enzymes SalI-SphI and BglII-ScaI, respectively, and accommodated in the disruption plasmid pCUB6K1 in a four-fragment ligation. pCUB6K1 comprises the URA3 marker flanked by the hisG gene from the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium resistance gene (2). This DNA was digested with NsiI and SpeI to force recombination at the SHO1 locus following the URA blaster scheme (24). Genomic DNAs were digested with EcoRI and probed with the 0.83-kb 5′ region of the gene for Southern hybridization to ensure proper genetic deletion. This strategy was utilized for the deletion of SHO1 on either the wild-type (RM1000), hog1 (strain CNC15), or ssk1 (strain CSSK21U) background. For the reintegration of the SHO1 gene, a 1.991-kbp fragment which also included the SHO1 promoter was amplified and subcloned in pGEMT using the oligonucleotides piSHO1 upper and piSHO1 lower (Table 2). A StuI-NaeI fragment was then accommodated in the blunted HindIII restriction site of the plasmid pGFP-URA3 (26). A ClaI restriction site was eliminated by digesting the plasmid with the enzymes StuI and SphI and subsequent self-ligation, generating the plasmid piSHO-GFP. We used ClaI for the reintegration of the SHO1-green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion in the sho1 mutant (REP4 strain).

TABLE 2.

List of primers used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| SHOUP1 | GGGGTCGACTAGTAGTGTCACAA |

| SHOLP2 | CTACGCATGCAATGTGTGAATGT |

| SHO3N | CTAGATCTGTCCTTCAAATTATG |

| SHO4N | TGAGTACTGTAATACCTCCAAAT |

| piSHO1 upper | CCAGGCCTAGTGTCACAAAACCAATGTAAACA |

| piSHO1 lower | GGAGGCCTACCACCACCAGTATCTAATAATTTAAC |

Protein extracts and immunoblot assays.

For kinetics assays, overnight cultures were diluted in fresh YEPD media to an A600 of 0.05 and grown until they reached an A600 of 1 at 37°C and 200 rpm. H2O2 (10 mM) or NaCl (1.5 M) was then added to the cultures, and samples were taken 2, 10, 30, and 60 min after the addition of the compound. To check the response to these compounds, we followed the same procedure and used different concentrations of H2O2 (1, 2.5, 5, 10, and 20) and NaCl (0.8, 1, and 1.5 mM); the samples were collected after 10 min of exposure to the compound. The procedures employed for cell collection, lysis, protein extraction, fractionation by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transfer to nitrocellulose membranes have been previously described (51). Anti-phospho-p44/p42 MAP kinase (MAPK) (Thr202/Tyr204) antibody (New England Biolabs) was used to detect dually phosphorylated Mkc1 and Cek1 MAPKs (indicated as Mkc1-P and Cek1-P on the figures); phospho-p38 MAP kinase (Thr180/Tyr182) 28B10 monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and ScHog1 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used to detect the phosphorylated Hog1 (indicated as Hog1-P on the figures) and Hog1 proteins, respectively. Western blots were developed according to the manufacturer's conditions using the Hybond ECL kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). To equalize the amount of protein loaded, samples were analyzed by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm and then by Coomassie staining. In addition, the anti-ScHog1 signal was used both as an internal control in those experiments concerning activation of CaHog1 and as an additional loading control when other MAP kinases were analyzed; this antibody was sometimes mixed with compatible antibodies as internal controls.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The 2,254-bp fragment from clone 58 has been sequenced and deposited in the EMBL database under accession number AJ272003.

RESULTS

Candida albicans SHO1 complements S. cerevisiae sho1 mutants.

Previous work from our group demonstrated the essential role of HOG1 in adaptation to osmotic stress by increasing the glycerol content in response to stimuli, such as sorbitol or sodium chloride (2). With the purpose of characterizing this phenomenon in more detail, we devised a heterologous genetic screening for the isolation of other elements of a putative HOG pathway in C. albicans (see Materials and Methods). Three clones were selected from a multicopy library able to complement an S. cerevisiae ssk2 ssk22 sho1 mutant (strain MY007) but not an ssk2 ssk22 ste11 mutant (strain FP50) (Table 1) which shared a common DNA region. Sequencing of a 2,254-bp fragment from clone 58 (deposited with accession number EMBL AJ272003) revealed a putative ORF of 1,164 bp, potentially encoding a 387-amino-acid protein homologous to S. cerevisiae (33.8 identity), Kluyveromyces lactis (33.6 identity), and Candida utilis (39.2 identity) Sho1 proteins. A bioinformatic analysis using the SMART software (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) predicted that, similar to S. cerevisiae Sho1p, C. albicans Sho1p contained 4 putative transmembrane domains (amino acids 13 to 33, 43 to 63, 69 to 89, and 104 to 124) and a C-terminal SH3 domain (amino acids 329 to 386) that would be responsible for interacting with a putative Pbs2 MAP kinase kinase (see Fig. 10) (65). The predicted Sho1 protein also showed significant similarity (E < 10 to 5 within the amino acids 333 to 384) to two hypothetical actin-binding proteins from this organism (CaO19.2699 and Bzz1p) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 10.

Proposed model. Schematic diagram showing the activating (→) or inhibitory (⊥) stimuli leading to activation of the MAP kinases Cek1, Mkc1, and Hog1 in C. albicans in response to different stimuli (see box at top of figure). The putative hypothetical elements that could lead to the activation of the corresponding MAP kinase in response to osmotic or oxidative stress are shown as question marks.

Deletion of the SHO1 and/or SSK1 gene has minor effects on sensitivity to osmotic stress.

To determine the role of Sho1 in C. albicans, we deleted this gene using the URA3 blaster strategy (24). For this purpose, 5′ and 3′ PCR-amplified regions were accommodated in the pCUB6K1 plasmid (a derivative of pCUB-6 [24] with a kanamycin resistance cassette instead of β-lactam resistance to facilitate the subcloning steps) and used to delete the C. albicans SHO1 ORF (see Materials and Methods for additional technical details). The disruption resulted in a set of constructions in which both the Ura+ and Ura− backgrounds were obtained. Ura+ strains were used in all experiments, unless otherwise stated, to avoid the putative effects of uracil auxotrophy in cellular growth and physiology (42). We also disrupted this gene in a hog1 background (strain CNC15) (Table 1) to establish its relationship with this gene.

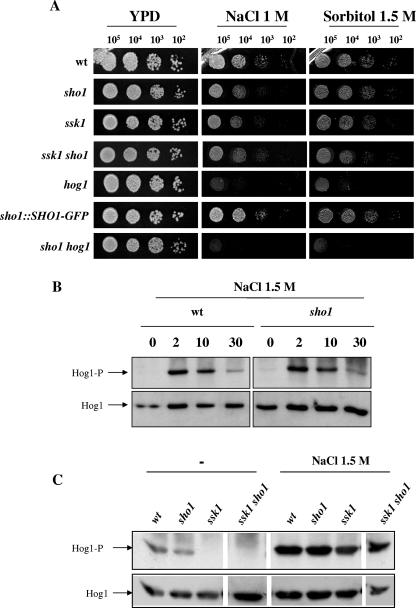

The role of Sho1 in resistance to osmotic stress was first investigated by plating exponentially growing cells on solid media supplemented with different types of osmolytes (see Materials and Methods). The sho1 mutant was found to be slightly sensitive to osmotic stress when using 1 M sodium chloride in this spot assay on solid medium (Fig. 1A). A higher concentration of solute also resulted in growth defects, more evident after prolonged incubation times. This result contrasts with the behavior of hog1 mutants, the growth of which was severely impaired at either 1 M (Fig. 1A) or 1.5 M NaCl (2, 72). This phenotype was not found to be restricted to Na+ ions, because sorbitol at 1.5 M (Fig. 1A) and 2 M (not shown) similarly inhibited the growth of hog1 cells but only slightly inhibited the corresponding growth of the sho1 mutant. The effect of 1.5 M sorbitol was, in any case, less intense than 1 M NaCl, in accordance with the chemical nature of both compounds. The double sho1 hog1 mutant displayed an osmosensitivity similar to that of hog1. The effect of SHO1 deletion on osmosensitivity was reversed upon integration of a functional SHO1-GFP fusion (Fig. 1A) in the genome of sho1 mutant cells at the SHO1 locus.

FIG. 1.

Osmotic response of the sho1 mutant. (A) 105, 104, 103, and 102 exponentially growing cells (from a culture at an A600 of 1) of strains wt (RM100), hog1 (CNC13), sho1 (REP3), sho1 hog1 (REP8), sho1::SHO1-GFP (REP5), ssk1 (CSSK21), and ssk1 sho1 (REP12) were spotted on solid agar plates of YEPD rich medium supplemented with sorbitol and sodium chloride at the concentrations indicated. Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C and scanned. (B) Sho1-dependent activation of Hog1 under osmotic stress was studied. Overnight cultures of the strains wt (RM100) and sho1 (REP3) were inoculated in fresh YEPD medium to an A600 of 0.05. At an A600 of 1, the same volume of 3 M NaCl (in YEPD) was added to the cultures to reach the final concentration of 1.5 M NaCl. Samples were taken at the times indicated and processed for the preparation of a total protein extract (see Material and Methods). The presence of phosphorylated Hog1 (Hog1-P) was visualized by probing a blot with an anti-phospho p38 antibody, and Hog1 protein (Hog1) was detected by using anti-ScHog1 polyclonal antibody. The labels indicate the number of minutes after the addition of the osmostress agent. (C) Hog1 phosphorylation was analyzed in wt, sho1, ssk1, and ssk1 sho1 exponentially growing cells (A600 = 1) in the absence (left) or presence (right) of 1.5 M NaCl (10 min of exposure to this agent). In parallel, another portion of the culture was subjected to 10 mM H2O2 instead of osmotic stress and processed in a similar way (shown in the next figure). The autoradiography was intentionally overexposed. Lanes are arranged in this figure from a scanned Western blot (as shown by blank intermediate lines) to avoid incorporation of samples not related to this particular experiment. They correspond to the same experiment and were processed simultaneously in the same gel.

These results could be consistent with the existence of two different input branches of the HOG pathway in this organism (see below) and with Sho1 being an upstream mediator of one of them that would be involved in the transmission of the signal to the downstream Hog1 MAP kinase in response to osmotic stress. To test this hypothesis, we deleted the SHO1 gene in an ssk1 background (strain CSSK21U) (Table 1) and analyzed its osmosensitivity. Under these conditions, the behavior of the ssk1 mutant was almost like that of the wild-type cells, and the double ssk1 sho1 mutant showed the slight sensitivity characteristic of sho1 cells (Fig. 1A). However, ssk1 sho1 cells did not behave as osmosensitively as do hog1 cells, a result that suggests that Hog1 is still able to be activated in response to high osmolarity in these mutants. This assumption was tested biochemically using antibodies against the TGY motif of stress-activated MAP kinases that detect Hog1 phosphorylation. Osmotic stress (1.5 M NaCl) induced a quick (normally detectable around 2 min) phosphorylation of Hog1 in both wild-type and sho1 cells and following similar kinetics (Fig. 1B), in accordance with the minor role of Sho1 under these conditions. As suggested by the phenotypic analyses, 1.5 M NaCl induced a clear activation of Hog1, in both ssk1 and ssk1 sho1 mutants, evidenced 10 min after addition of the solute to an exponentially growing culture (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, under “normal” conditions (that is, in the absence of osmotic stress), we detected a basal activation of Hog1 that was abolished in the ssk1 background (that is, ssk1 and ssk1 sho1 cells) (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that both Ssk1 and Sho1 are not necessary for the osmotic stress-induced activation of Hog1.

SHO1 mediates resistance to oxidative stress, but its deletion does not impair signaling to the Hog1 MAP kinase in response to this stimulus.

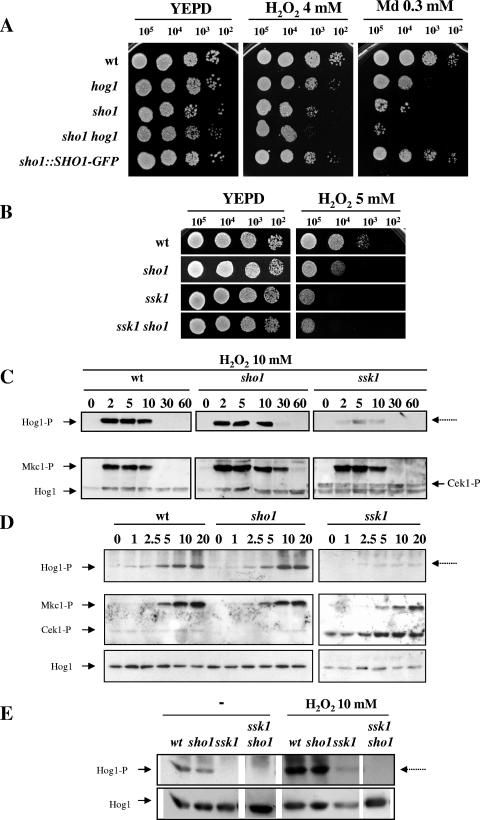

hog1 mutants are sensitive to oxidative stress (3), a trait that has been proposed to explain its drastic reduction in virulence in a mouse model of systemic infection (2). sho1 mutants were also found to be sensitive to different oxidants: cells were sensitive to 4 mM and 5 mM hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 2A and B) and, more clearly, to menadione (0.3 mM [Fig. 2A] and 0.4 mM [data not shown]) in a standard solid medium assay in which exponentially growing cells were plated on media with different concentrations of oxidants. This different behavior of sho1 mutants versus the wild type, related to the oxidant used in the assay, may reflect the fact that both compounds, hydrogen peroxide and menadione, act by different mechanisms, the latter being a superoxide radical generator. The sensitivity of sho1 mutants was even higher than that observed for hog1 mutants in this assay and was reverted upon reintegration of a SHO1-GFP functional chimera (Fig. 2A). As shown in Fig. 2A, the double sho1 hog1 mutant was found to be more sensitive than any of the single mutants, a result that indicates that the role of the Sho1 protein in mediating resistance to oxidative stress is partially independent of Hog1 (see later). These results were also evident in diffusion assays (see Materials and Methods). Under these conditions, the measured halos were as follows (means ± standard deviations of the results from three independent experiments): with hydrogen peroxide, wild type (wt), 27.2 ± 0.6 mm; hog1, 29.3 ± 0.65 mm; sho1, 30.1 ± 0.7 mm; sho1 hog1, 32.2 ± 0.8 mm; with menadione, wt, 21 ± 0.45 mm; hog1, 24.4 ± 0.54 mm; sho1, 26.2 ± 0.45 mm; sho1 hog1, 29 ± 0.56 mm. The sensitiveness of sho1 was not found to be exclusive of exponentially growing cells. Stationary-phase cells behaved similarly, although they were found to be intrinsically more resistant to oxidants (data not shown), in agreement with what has already been observed in S. cerevisiae cells (9). Collectively, these results support a role for Sho1 in the adaptive oxidative stress response in C. albicans.

FIG. 2.

Oxidative stress response in HOG pathway mutants. (A) Serial dilutions of exponentially growing cells of the strains wt (RM100), hog1 (CNC13), sho1 (REP3), sho1 hog1 (REP8), and sho1::SHO1-GFP (REP5) (from a culture at an A600 of 1) were spotted onto plates supplemented with hydrogen peroxide and menadione at the concentrations indicated. (B) The hydrogen peroxide susceptibility of ssk1 (CSSK21) and ssk1 sho1 (REP12) mutants was analyzed by solid medium studies in the presence of a 5 mM concentration of the mentioned oxidant. (C) The role of Sho1 and Ssk1 in the transmission of H2O2 signal to Hog1 was analyzed by Western blotting. H2O2 (10 mM) was added to exponentially growing cultures (at an A600 of 1), and samples were collected at 2, 5, 10, 30, and 60 min after treatment with the oxidant. phospho-Mkc1 (Mkc1-P) and phospho-Cek1 (Cek1-P) were detected by blotting the membranes with the anti-phospho-p44/p42 antibody. (D) Exponentially growing cultures of the mentioned strains were challenged with 0, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 mM H2O2 (indicated at the top of each lane), and the pattern of MAP kinase activation was detected after 10 min. Cells were collected and processed for immunodetection analysis to detect the activated (-P) forms of the MAP kinases. (E) Hog1 phosphorylation was analyzed in a ssk1 sho1 mutant under oxidative stress. Exponentially growing cultures of the indicated strains (A600 of 1) (−) were treated with 10 mM hydrogen peroxide for 10 min, and samples were processed as described above. Control lanes of this experiment are exactly the same as those from Fig. 1C, as this experiment was performed simultaneously, and are included here to facilitate comparison.

Oxidative stress activates Hog1 in C. albicans (3). When 10 mM hydrogen peroxide was added to exponentially growing wild-type and sho1 cells, Hog1 was quickly phosphorylated in both strains (Fig. 2C, first two panels). The maximum signal observed for Hog1 in the sho1 mutant was similar to that of wild-type cells (as determined using densitometry). The time course of this activation was also investigated, with the signal reaching, for both sho1 and wild-type strains, a maximum 10 min after the addition of the oxidant and quickly decreasing, returning to its original levels 30 min after the challenge. This result indicates that SHO1 deletion does not substantially impair signaling to Hog1 in response to oxidative stress. We also performed experiments in which the Hog1 MAP kinase phosphorylation state was measured in response to increasing concentrations of oxidants to determine if it was the threshold, instead of the kinetic, which was altered in sho1 cells. Hydrogen peroxide was added from 1 to 20 mM to exponentially growing cells, and 10 min after the addition of the stimulus, the pattern of MAP kinase activation was analyzed. As observed in Fig. 2D, 1 mM hydrogen peroxide was sufficient to activate the pathway, although maximum levels were achieved at 10 to 20 mM hydrogen peroxide concentrations; over these values (50 and 100 mM), phosphorylation decreased, most likely as a consequence of cellular damage (data not shown). However, no significant differences were observed between the mutant and wild-type strains with respect the Hog1 MAP kinase activation. The behavior of Mkc1, the MAP kinase of the cellular integrity pathway, the activation of which is also dependent on this stimulus (F. Navarro-García, submitted for publication), was similar to that of Hog1, also activated in response to hydrogen peroxide. However, in the sho1 mutant, the phospho-Mkc1 signal was more prolonged in time, and after 30 min, it could be still detected in the sho1 mutant (Fig. 2C) but not in wild-type cells.

In contrast to these observations, a clear role for Ssk1 in the transmission and resistance to oxidative stress was observed. As already documented (13), an ssk1 mutant was found to be sensitive to hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 2B), even more than a sho1 mutant, the double sho1 ssk1 was found to be as sensitive as an ssk1 mutant (Fig. 2B), and deletion of SHO1 in an ssk1 background did not aggravate this phenotype. When the MAP kinase phosphorylation pattern was analyzed, it was observed that an ssk1 mutant drastically impaired oxidative stress signaling to the Hog1 MAP kinase in response to oxidative stress when using the kinetic (Fig. 2C) or threshold (Fig. 2D) assay. Interestingly, ssk1 deletion did not completely impair signaling to Hog1, and a certain residual activation can be observed, in both the kinetic and threshold assays in the ssk1 mutant (Fig. 2C, D, and E). This activation was, however, completely abolished in the double ssk1 sho1 mutant (Fig. 2E), as determined after a 10-min pulse with 10 mM hydrogen peroxide, indicating that Sho1 does play a minor role in the transmission of stress under these conditions. Interestingly, deletion of SSK1 did not impair signaling to the Mkc1 MAP kinase in response to oxidative stress, indicating the specificity of this kinase within the HOG pathway (Fig. 2C and D).

We conclude from these sets of experiments that Sho1 is not essential for the transmission of the oxidative stress-induced signal to the Hog1 MAP kinase in C. albicans which takes place mainly through the Ssk1 protein, even though it has a clear role in mediating resistance to oxidants in this organism.

sho1 mutants display defects related to cell wall biogenesis.

Work with S. cerevisiae has shown that Sho1 plays a role in the STE vegetative growth pathway (44). This pathway, which shares some elements of the invasive and mating pathway in S. cerevisiae, and defects in protein mannosylation, such as those that occur in S. cerevisiae och1 mutants, activate the pathway in a Sho1-dependent manner (18). These results prompted us to analyze the role of Sho1 under vegetative growth and its relationship with the biosynthesis and structure of the cell wall in C. albicans.

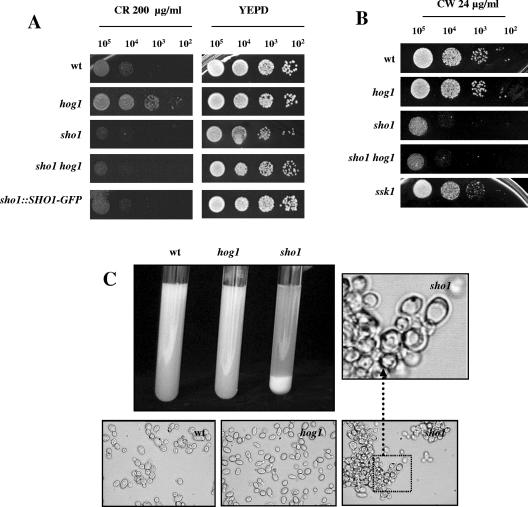

Different lines of evidence indicate that Sho1 plays a role in cell wall biogenesis. First, sho1 mutants are sensitive to Congo red, a compound that interferes with cell wall polymer assembly. sho1 cells were impaired in growth on YEPD plates supplemented with 200-μg/ml Congo red (Fig. 3A) compared to wild-type cells, and a similar behavior was observed on 250-μg/ml Congo red plates (data not shown). In contrast and as previously reported, the hog1 mutant was resistant to this compound, a phenotype more evident on 250-μg/ml Congo red plates (Fig. 3A) (2). The double sho1 hog1 mutant gave a sho1 phenotype, resulting in sensitivity to this compound (Fig. 3A). This trait was also observed in mutants of the Cek1-mediated pathway because cek1, hst7, and cst20 (KSS1, STE7, and STE20 homologs) mutants were also similarly impaired in growth (data not shown). sho1 mutant cells showed sensitivity to 24-μg/ml calcofluor white, a compound that interferes with cell wall formation (Fig. 3B). This phenotype is again sho1 dependent but not hog1 dependent, as the double sho1 hog1 mutant behaved as a sho1 mutant. Finally, and perhaps consistent with the preceding observations, sho1 mutants spontaneously flocculated on normal liquid media, a trait that reflects alterations in their cellular surface. On liquid YEPD medium at 37°C, exponentially growing sho1 cells spontaneously aggregated and were deposited at the bottom of a culture tube after 2 to 5 min without swirling (Fig. 3C). Under these conditions, cells appeared clumped (Fig. 3C) (microscopic observations) with an altered morphology; calcofluor white staining revealed no drastic alterations in the pattern of chitin deposition on the external surface of the cell (data not shown). This phenotype was clearly different from that of hog1 cells, which behaved as wild-type cells in this assay.

FIG. 3.

Alterations in cell wall biogenesis in sho1 mutants. Serial dilutions of exponentially growing cells of the strains indicated (from a culture at an A600 of 1) were spotted onto plates supplemented with Congo red (CR) (A) or calcofluor white (CW) (B) at the concentrations indicated. (C) Stationary-phase cells from the strains indicated were inoculated in YEPD fresh medium, grown at 37°C until they reached an A600 of 1, and photographed 2 to 4 min after swirling of the cultures in a glass tube was stopped. Phase-contrast photographs were also taken under these conditions and are shown; a portion of the sho1 photograph is further amplified to appreciate its altered morphology.

In summary, the current description of the phenotype of sho1 mutants is consistent with this protein affecting the biogenesis of the cell wall of C. albicans.

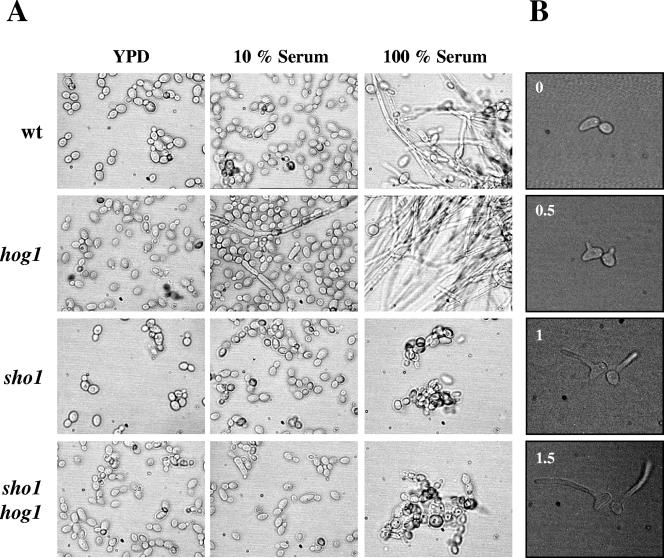

Sho1 plays a role in morphological transitions in C. albicans.

The dimorphic transition is a differentiation program characteristic of C. albicans (60) and is known to play a major role in C. albicans pathogenesis (37; see also reference 61 and references therein). Dimorphism can be induced by chemical signals (such as pH, proline, N-acetylglucosamine, or those present in serum) and is favored at high temperatures (37°C). When assayed at 30°C in serum (fully inducing conditions), sho1 cells were impaired in filament formation (Fig. 4A) with no evidence of germinative tubes. They showed, as previously indicated, an increased tendency to aggregate compared to wild-type cells. hog1 cells showed the characteristic hyperfilamentous phenotype already described (2) compared to the wild-type strain, more clearly evidenced on serum-limiting medium (5% or 10%) (Fig. 4A). The double sho1 hog1 mutant was also unable to undergo the dimorphic transition (Fig. 4A). Analysis of filamentation at 37°C in liquid cultures was difficult because of the starting aggregate phenotype, suggesting that dimorphic transition was not possible in sho1 mutants; however, when assayed on solid serum medium (1% agar serum) under a microscopic thermostated chamber, individual sho1 cells from exponentially growing cultures were able to filament. Germinative tubes were evident as early as 0.5 h at 37°C, and hyphae continued to develop normally (Fig. 4B). Calcofluor white staining revealed no alterations of the septa under these conditions (data not shown). This result indicates that sho1 cells have the machinery necessary to undergo the dimorphic transition but are handicapped to do so because of their tendency to aggregate.

FIG. 4.

Effect of Sho1 in the serum-induced morphological transition. (A) Stationary-phase cells were inoculated at 106 cells/ml in prewarmed YEPD medium (YPD), YEPD supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (10% Serum), or 100% serum (100% Serum). Phase-contrast microphotographs were taken after 3 h of incubation at 30°C. (B) The dimorphic transition of individual sho1 cells was studied on solid serum medium (1% agar serum) at 37°C. Hypha formation was monitored by phase-contrast microscopy, taking photographs at the times indicated (in hours).

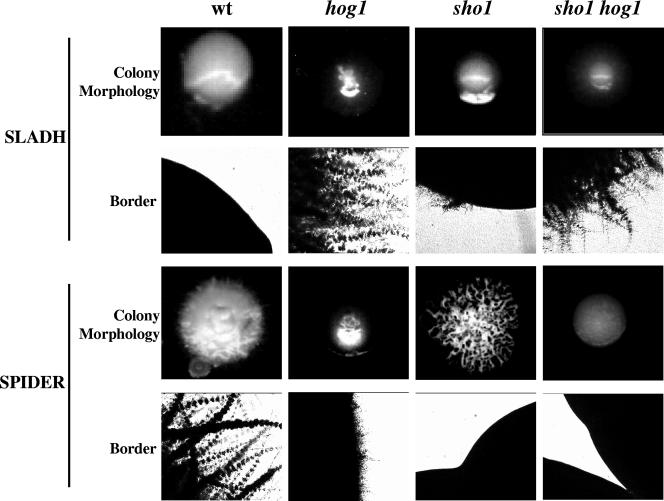

sho1 cells also showed an inability to invade the agar on some solid media that promote pseudohyphal formation, such as SLADH, a nitrogen-limiting medium (28), and Spider medium, a mannitol-containing medium (48). Deletion of SHO1 prevented cells from invading Spider medium solid plates, similar to what has been observed with hog1 cells (Fig. 5). Furthermore, its deletion in a hog1 background completely abolished the faint and limited agar invasion which is still observed in the hog1 mutant after prolonged incubation (Fig. 5). Deletion of SHO1 also abolished invasion on SLADH, as it does in S. cerevisiae, in clear contrast to the situation in hog1 cells that showed an increased ability to invade the agar. Deletion of SHO1 had no effect in a hog1 mutant, as the double mutant showed a hog1 phenotype and was still able to invade the agar (Fig. 5). This last result is contrary to what is observed for S. cerevisiae sho1 hog1 double mutants (62) and indicates a functional difference between this pathway in both organisms.

FIG. 5.

Effect of Sho1 on colonial morphology. Exponentially growing cells (from a culture at an A600 of 1) from wt (RM100), hog1 (CNC13), sho1 (REP3), and sho1 hog1 (REP8) were obtained, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and counted. Approximately 50 CFU were spread onto YEPD, SLADH, or Spider medium plates and incubated for 7 days at 37°C before photographs were taken. Colony morphologies and borders are shown for each medium and strain.

We conclude from the previous observations that Sho1 is not essential for filamentation but impedes morphological transitions in C. albicans under certain experimental conditions.

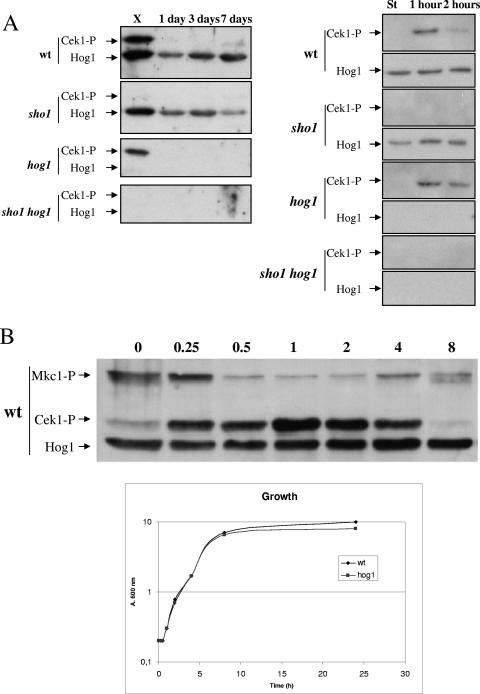

Sho1 controls the activation of the Cek1 MAP kinase.

The role of Sho1 in Cek1 activation was investigated. We first determined the dependence of Cek1 phosphorylation on growth conditions and checked the behavior of this MAP kinase upon entry into the stationary phase. As shown in Fig. 6A (left panel), Cek1 was phosphorylated in wild-type exponentially growing cells but not in cells from cultures 1, 3, or 7 days old or stationary phases of different lengths. This phenomenon also occurred in the hog1 mutant, indicating that despite the constitutive activation of Cek1 in these mutants (Navarro-García, submitted; see also below), Cek1 is effectively deactivated in the stationary phase. Cek1 activation was also analyzed in hog1, sho1, and sho1 hog1 mutants. No phosphorylated Cek1 could be detected in exponentially growing cells in the sho1 background (either sho1 or sho1 hog1) (Fig. 6A), indicating that Sho1 is essential for the activation of the Cek1 MAP kinase under these conditions. In opposite experiments, when 1-day-old stationary-phase cultures were allowed to grow upon dilution into fresh medium, Cek1 phosphorylation could be detected after 1 or 2 h of growth (Fig. 6A, right panel); this occurred in wild-type and hog1 mutant cells but not in those that lack SHO1 (sho1 and sho1 hog1), indicating the control that this protein exerts on Cek1 phosphorylation upon growth resumption. To analyze this phenomenon more precisely, an overnight culture was diluted in prewarmed rich YEPD medium to an A600 of 0.2, and samples were taken at the times indicated and processed for Western blot analysis (Fig. 6B). Cek1 became phosphorylated as early as 15 min after dilution in YEPD rich medium, reaching a maximum at 1 to 2 h (A600 = 0.3 to 0.4). However, the signal decreased again after 4 h of growth (A600 = 1.7) and completely disappeared after 8 h (A600 = 6.6) or 24 h (A600 = 8) (Fig. 6B). No alteration in the pattern of Hog1 phosphorylation was observed in these experiments (data not shown). However, and interestingly, the pattern of Mkc1 activation was found to be opposite that of Cek1, and phosphorylated Mkc1 accumulated in stationary-phase cells compared to exponentially growing cells. The patterns of activation of the Mkc1 and Cek1 MAP kinases in the hog1 mutant were found to be similar qualitatively, although the phospho-Mkc1 signal in stationary-phase cells was found to be higher than that of wild-type cells (not shown). Again, a sho1 mutant completely abolished the activated Cek1 signal upon growth resumption and behaved similarly to wild-type cells regarding Mkc1 activation, maybe with a slightly prolonged activation state (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Growth phase-dependent activation of the Cek1 MAP kinase. (A) Left panel: cells from 1-, 3-, and 7-day stationary-phase cultures (indicated at the top of the lane) were analyzed for MAP kinase activation and compared to exponentially growing cells at an A600 of 1 (labeled with X, for exponentially). Cells were collected and prepared for Western blot analysis. Right panel: 1-day stationary-phase cultures of the mentioned strains (wt [RM100], sho1 [REP3], hog1 [CNC13], and sho1 hog1 [REP8]) (labeled with St, for stationary) were diluted at an A600 of 0.2 and allowed to grow. Samples were taken after 1 and 2 h (indicated in each lane) and processed for the analysis of Cek1 activation. In both panels, Cek1-P refers to phospho-Cek1 (detected with anti-phospho-p44/p42 antibody), while Hog1 refers to CaHog1 protein (detected with anti- S. cerevisiae Hog1 antibody). (B) A stationary-phase culture of the wild-type strain was diluted in YEPD medium at an A600 of 0.2, and samples were taken at the times indicated (in hours) and processed for MAP kinase activation. The symbols are similar to those in panel A. The growth in mass, as determined using the absorbance of the cultures, is shown below.

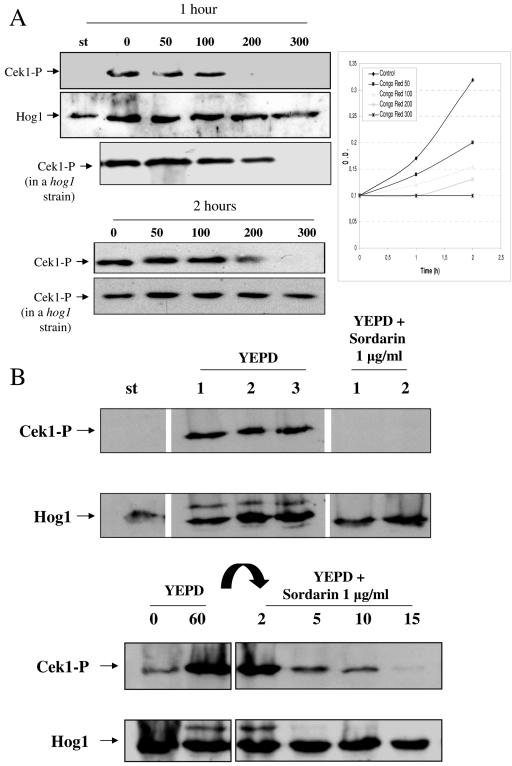

The relationship of Cek1 phosphorylation with cellular growth was further investigated using the cell wall assembly inhibitor Congo red. When stationary-phase wild-type cells were diluted in fresh prewarmed medium (at an A600 of 0.1) to which Congo red at different concentrations (50 to 300 μg/ml) was added, resumption of growth was impeded in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7A). One hour after the dilution, no activation was detected at a Congo red concentration of 200 μg/ml in wild-type cells, consistent with an effective block in growth. A small increase of Cek1 phosphorylation was detected after 2 h, in agreement with the existence of a slight cellular mass increase at this time (as determined by using the A600 of the culture). No activation was detected with 300-μg/ml Congo red at any time, consistent with a complete lack of growth in mass under these conditions. A similar qualitative effect was observed in a hog1 mutant, although higher concentrations of Congo red were required, in agreement with the increased resistance to this compound of these mutants (Fig. 7A).

FIG. 7.

Growth-dependent activation of the Cek1 MAP kinase. (A) Stationary-phase cells of the wt strain (RM100) were diluted at an A600 of 0.1 in either YEPD or YEPD in the presence of Congo red at 50, 100, 200, and 300 μg/ml. Samples were collected after 1 and 2 h of growing at 37°C, and cells were processed for MAP kinase phosphorylation by Western blotting analysis. The increase in A600 is shown in the diagram at the right. Symbols are the same as described in the legend to Fig. 6. Results for the hog1 mutant under the same conditions are also shown. (B) An overnight culture of a wt strain (labeled st) was diluted in fresh YEPD to an A600 of 0.2 and incubated at 37°C, taking samples after 1, 2, and 3 h of growth in these conditions (shown in each lane; YEPD lanes 1, 2, and 3). A portion of the overnight culture was also transferred to a prewarmed flask with YEPD medium, where 1 μg/ml sordarin was added, and samples were taken after 1 and 2 h of incubation at 37°C and processed (labeled YEPD + sordarin, lanes 1 and 2). Lanes are arranged in this figure from a scanned Western blot (as shown by blank intermediate lines) to avoid incorporation of samples not related to this particular experiment. They correspond to the same experiment and were processed simultaneously in the same gel. (C) Similarly, stationary growing cells of a wt strain were diluted in fresh YEPD to an A600 of 0.2 and incubated at 37°C. After 1 h, 1 μg/ml sordarin was added. Samples were collected at the times indicated in each lane (in minutes). Symbols are same as described in the legend to Fig. 6.

This behavior is not exclusive of cell wall assembly inhibitors, as it was also observed using sordarins, inhibitors of eukaryotic protein synthesis (22, 35). When stationary-phase cells were diluted in fresh YEPD medium containing 1 μg/ml of sordarin, a concentration effectively inhibiting growth in mass, no phosphorylated Cek1 was observed after 1 or 2 h (Fig. 7B), in contrast to the behavior of cells growing in YEPD medium. When actively growing cells (60 min after resumption of growth in a medium without sordarins) were transferred to a medium containing 1 μg/ml of sordarin, the phospho-Cek1 signal decreased and was almost undetectable in about 30 min (Fig. 7C), again consistent with lack of growth as determined by A600 measurements (not shown).

Both sets of experiments indicate that although no direct and quantitative correlation can be established between Cek1 phosphorylation and the increase in absorbance of the cultures, (i) a blockage in cellular growth results in a failure to detect phosphorylated Cek1 and (ii) this process is dependent on Sho1.

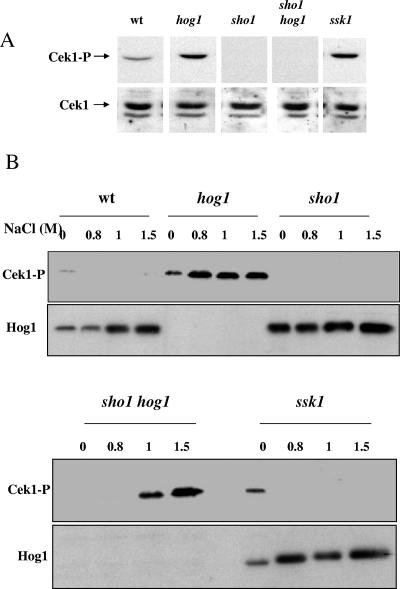

The Hog1 MAP kinase represses the Cek1-mediated pathway.

When we analyzed the behavior of the Cek1 MAP kinase in hog1 mutants, we determined that the Cek1 MAP kinase is constitutively activated in hog1 mutants (Fig. 8B) (4) (F. Navarro-García, B. Eisman, S. M. Fiuza, C. Nombela, and J. Pla, submitted for publication) when the cells are not in stationary phase. The same phenotype was observed in ssk1 mutants (Fig. 8A), indicating that the HOG pathway repressed Cek1 activation in the absence of osmotic stress. However, in sho1 mutants (sho1, sho1 hog1, and sho1 ssk1), Cek1 activation was blocked under these basal conditions (Fig. 2 and 8), indicating the dependence of this activation upon Sho1. Unexpectedly, osmotic stress, previously shown to trigger Hog1 phosphorylation (3), also activated Cek1; 0.8 to 1.5 M sodium chloride induced a quick (10 min after the addition of the stimulus) osmotic stress-induced phosphorylation of Cek1 in a hog1 mutant but not in wild-type cells under similar conditions (Fig. 8A). The highest concentrations of sodium chloride (1 and 1.5 M) triggered Cek1 phosphorylation not only in hog1 but also in sho1 hog1 mutants, while it could not be detected in wild-type and ssk1 strains (Fig. 8). This cross talk has been already documented in the S. cerevisiae model, where osmotic stress induces activation of the pheromone response pathway (62). These results show (i) that the HOG pathway represses the Cek1-mediated pathway at the level of the Hog1 MAP kinase upstream of Sho1 and (ii) that Cek1 can be activated in response to high osmolarity in hog1 mutants in a Sho1-independent manner.

FIG. 8.

Cek1 can be activated in a Sho1-independent manner under high osmolarity. (A) Pattern of activation of Cek1 in the strains wt (RM100), hog1 (CNC13), sho1 (REP3), sho1 hog1 (REP8), and ssk1 (CSSK21) under exponential growth in YEPD medium. Arrows indicate the phosphorylated Cek1 protein (Cek1-P) and Cek1 (Cek1) protein as revealed by Western blotting using either anti-p44/p42 antibodies (upper panel) or a rabbit polyclonal serum against a GST-Cek1 fusion (lower panel). Lanes are arranged in this figure from a scanned Western blot (as shown by blank intermediate lines) to avoid incorporation of samples not related to this particular experiment. They correspond to the same experiment and were processed simultaneously in the same gel. (B) Stationary growing cells of the strains wt (RM100), hog1 (CNC13), sho1 (REP3), sho1 hog1 (REP8), and ssk1 (CSSK21) were diluted in fresh medium to an A600 of 0.05 and incubated at 37°C until they reached an A600 of 1. A twofold-concentrated NaCl-YEPD (0, 1.6, 2, and 3 M) was then added to the cultures to reach the final concentration indicated at the top of each lane (0, 0.8, 1, and 1.5 M). After 10 min, cells were collected, processed as indicated (see Materials and Methods), and analyzed for MAP kinase activation.

Deletion of the SLN1 histidine kinase results in Hog1 activation.

The SLN1 histidine kinase has been shown to be involved in osmotic as well as oxidative stress sensing in S. cerevisiae by means of phosphotransfer to the MAP kinase kinase kinase SSK1 and the transcription factor SKN7 (46, 47, 77). Its role as an upstream component of the HOG pathway is uncertain, since no clear phenotype is observed from the analysis of this protein, either alone or in combination with other histidine kinases (83). We therefore decided to determine the role of this component within the HOG pathway. A phenotypic analysis revealed that sln1, nik1, or hk1 mutants do not display sensitivity to sorbitol (2 M) compared to wild-type cells (data not shown).

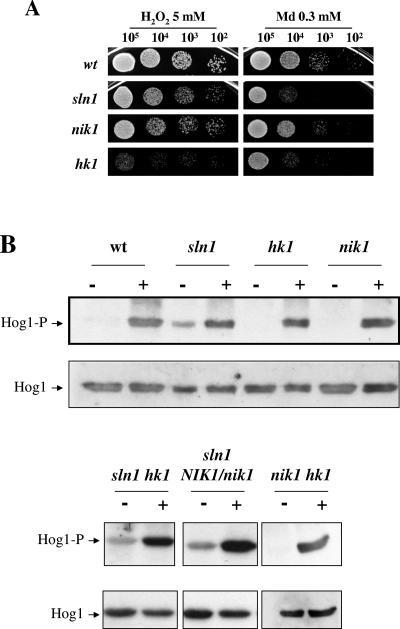

Their role in the oxidative stress response was investigated on solid media. hk1 mutants were found to be sensitive to 5 mM hydrogen peroxide and 0.3 mM menadione, and the sln1 mutant was found to be sensitive only to 0.3 mM menadione, while the nik1 sensitivity was similar to that of wild-type cells (Fig. 9A). When the MAP kinase pattern was analyzed in wt, sln1, hk1, nik1, sln1 hk1, sln1 NIK1/nik1, and nik1 hk1 mutants, Hog1 was found to be constitutively active in sln1 mutant cells but not in hk1 or nik1 cells (Fig. 9B); this wasalso observed in sln1 hk1 or sln1 NIK1/nik1 mutants (that is, sln1 background) (data not shown), indicating that the absence of SLN1 is responsible for this effect. sln1 cells were, however, still able to further activate this MAP kinase upon hydrogen peroxide addition (Fig. 9B), indicating that deletion of SLN1 does not fully induce the pathway; this also occurred in hk1 and nik1 mutants that behaved as wild-type cells.

FIG. 9.

sln1 mutants constitutively activate the HOG pathway. (A) Exponentially growing cells (A600 of 1) (105, 104, 103, and 102 cells) were spotted onto YEPD plates supplemented with 5 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and 0.3 mM menadione (Md). The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 24 h and scanned. (B) Hog1 phosphorylation in histidine kinase mutants upon H2O2 treatment. Overnight cultures of the strains indicated were reinoculated into fresh YEPD medium to an A600 of 0.05 and incubated at 37°C. At an A600 of 1, samples were taken as a control (−) before adding H2O2 to a final concentration of 10 mM. After 10 min, cells were collected (+) and processed for MAP kinase activation.

These results demonstrate a role for the SLN1 sensor in the activation of the Hog1 MAP kinase under basal conditions.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this work was to characterize in detail the role of the Sho1 adaptor protein in C. albicans. We present here evidence that this protein (i) plays an essential role in morphogenesis/cell wall biogenesis, (ii) mediates oxidative stress resistance, and (iii) controls the activation of the MAP kinase Cek1. The data obtained in this work can be accommodated in the model proposed in Fig. 10, in which Sho1 plays an essential role in the control of the Cek1 MAP kinase but only a minor role in the activation of Hog1.

We found that Sho1 participates in morphogenesis and cell wall biogenesis in this fungus. In fact, a starting hypothesis to this work was that Sho1 could be a sensor of filamentous growth in pathogenic fungi, since deletion of SHO1 in S. cerevisiae abolished pseudohyphal growth (62). In C. albicans, deletion of SHO1 also abolished pseudohyphal growth under nitrogen starvation on solid media, but in contrast to S. cerevisiae, this phenotype was suppressed by an additional deletion of HOG1. This result indicates that Hog1 exerts its repressive role at a different epistatic level than S. cerevisiae (where it acts downstream of Sho1) or that an alternative sensor could be responsible for the transmission of the signal under starvation (Fig. 10). Deletion of SHO1 also rendered cells defective in mannitol-induced hypha formation on solid medium. C. albicans hog1 mutants are hyperfilamentous and, under limiting stimuli (such as low concentrations of serum), display an enhanced ability to undergo the yeast-to-hypha transition (2). Although sho1 mutants are defective in hypha formation in response to serum at 30°C, they are able to undergo the yeast-to-hypha transition, suggesting that neither Cek1 activation nor the presence of the protein is essential for filament formation (16).

The role of Sho1 in cell wall biogenesis is evidenced by several observations. sho1 mutants display cell wall architecture modifications, resulting in an enhanced susceptibility to certain cell wall inhibitors (Congo red, calcofluor white) and an aggregation phenotype. We propose that Cek1 activation in C. albicans is responsible for the construction of a Congo red-resistant cell wall for several reasons. First, it is the only MAP kinase partially activated under these conditions. Second, cek1, as well as hst7 and cst20, mutants (homologs of the kss1, ste7, and ste20 mutants in S. cerevisiae), which would be defective in Cek1 activation, are also sensitive to Congo red. Furthermore, ssk1, as well as hog1 (Navarro-García et al., submitted) and pbs2, mutants (4) that cause constitutive activation of the Cek1 kinase are resistant to this compound. Consistent with this hypothesis, deletion of SHO1 in an ssk1 and a hog1 background (Fig. 2B) suppresses the Congo red resistance phenotype as well as Cek1 basal activation in these mutants, in accordance with the role of Sho1 in the control of Cek1 activation (see below). In S. cerevisiae, deletion of HOG1 and PBS2 results in modifications of the cell wall (25, 34, 36), and alterations of the cell wall have also been observed in mutants of the HOG pathway in C. albicans (2, 40, 41). We propose that Cek1 is activated in certain HOG pathway mutants to compensate for their defects in cell wall architecture.

We demonstrated that Cek1 is also activated in response to the transfer from the stationary phase to the exponential mode of growth and that Sho1 controls this process. This activation is evident as early as 15 min after dilution of the culture, does not drastically depend on the initial A600 or depth of the stationary phase, is dependent on the growth inhibition caused by protein synthesis inhibition, and takes place in mutants of the HOG pathway were Cek1 is hyperactive. An exact and direct correlation of Cek1 activation with cellular growth cannot be established; although failure of growth may result in absence of signal, we are still able to detect robust signals with reduced growth. Since growth resumption is a complex process, we cannot determine at this stage whether nutritional and/or cell wall remodeling signals trigger Cek1 activation. Furthermore, quorum sensing could account for it, since tyrosol and farnesol have been recently identified in C. albicans and shown to be involved in morphogenesis (14, 32, 74) and farnesol has been claimed to decrease mRNAs of HST7 and CPH1. Therefore, upon dilution from stationary phase, relief of quorum-sensing-mediated repression could lead to transient activation of the Cek1 kinase (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

We must emphasize that, although sho1 mutants failed to activate Cek1, it is also evident that Sho1 is only not involved in Cek1 activation for two reasons. Cek1 can be activated in response to sodium chloride in a partially Sho1-independent manner in the absence of the Hog1 kinase, and phenotypes such as aggregation or oxidative stress sensitivity are not observed in cek1 mutants (our data not shown). Therefore, there are Cek1-independent functions of Sho1.

One of these functions is osmotic and oxidative stress. We demonstrated that ssk1 mutants, but not sho1 mutants, are defective in Hog1-mediated oxidative stress-induced activation (13) in response to a wide range of concentrations of hydrogen peroxide and that Sho1 has a minor role in this process only detectable when SSK1 is absent. Consequently, it is the SSK1 branch and not the SHO1 branch, which is the main input mechanism of Hog1 activation in response to oxidants. This is reinforced by genetic data using sln1 mutants, since these mutants constitutively activate the Hog1 pathway under basal conditions (that is, in the absence of stimulus), as does that which has been observed in S. cerevisiae, where deletion of SLN1 leads to an increase of the unphosphorylated SSK1 that, in turn, leads to constitutive activation of the HOG pathway (66, 69). In this organism, SLN1 mediates phosphotransfer not only to the SSK1 but also to the SKN7 regulator (46) and SKN7 plays an important role in the oxidative stress response (39, 45, 53) as may be the case in C. albicans (76). However, since sln1 mutants are still able to fully activate the pathway in response to hydrogen peroxide, we suggest that another element upstream of Ssk1 may trigger the signal to the MAPK kinase kinase (MAPKKK). It must be emphasized that our data do not discard a role for the other histidine kinase (HK1 and NIK1) in signaling towards other MAP kinases; however, Sln1 seems to be the most relevant under basal conditions in the transmission of the signal toward the Hog1 kinase. Sho1 does, however, play a role in oxidative stress resistance without significantly impairing transmission of the peroxide signal to the Hog1 or the Mkc1 MAP kinase, both of which have been shown to be activated in response to oxidants (3; F. Navarro, unpublished). The additive sensitivity of the double sho1 hog1 mutant argues in favor of Hog1-independent mechanisms of oxidative stress resistance.

Finally, Sho1 plays a minor role in osmotic stress resistance, and the additional deletion of SSK1 in sho1 cells does not increase sensitivity. In S. cerevisiae, ssk1 sho1 mutants are also partially osmosensitive but still do not reach the sensitivity observed in ssk1 ste11, hog1, or pbs2 mutants (62). An interesting difference, however, is that S. cerevisiae ssk1 sho1 mutants failed to activate Hog1 under osmotic stress (63), while C. albicans ssk1 sho1 mutants were, as expected from the phenotypic analysis, able to activate Hog1 in response to osmotic stress. Msb2 was isolated as a putative sensor of osmotic stress, since ssk1 sho1 msb2 cells showed a behavior similar to hog1 or pbs2 mutants, and a triple msb2 ssk1 sho1 mutant was sensitive to this stress. A functionally similar gene in C. albicans could explain the apparent redundant role of the two branches described as well as some of the morphogenetic phenotypes of sho1 mutants (17).

In conclusion, our work demonstrates the existence of a pathway involved in cell wall biogenesis/morphogenesis and oxidative stress resistance, both of which are interconnected via the SHO1 adaptor protein. Future work is aimed at determining the degree of cross talk between the HOG and other MAP kinase pathways in this fungal pathogen.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. A. López Matas, R. de la Fuente, and M. L. Hernáez for contributions to the initial stages of this work. We also thank R. Calderone, M. Whiteway, A. Brown, and H. Yamada Okabe for sharing C. albicans strains and R. Alonso-Monge, F. Posas, and M. Molina for critical reading of the manuscript as well as suggestions for its improvement.

This work was supported by grants BIO2000-729 and BIO2003-00992 from MCYT.

Footnotes

E.R. dedicates this work to her parents.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alex, L. A., C. Korch, C. P. Selitrennikoff, and M. I. Simon. 1998. COS1, a two-component histidine kinase that is involved in hyphal development in the opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7069-7073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso-Monge, R., F. Navarro-García, G. Molero, R. Diez-Orejas, M. Gustin, J. Pla, M. Sánchez, and C. Nombela. 1999. Role of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Hog1p in morphogenesis and virulence of Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 181:3058-3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso-Monge, R., F. Navarro-García, E. Roman, A. I. Negredo, B. Eisman, C. Nombela, and J. Pla. 2003. The Hog1 mitogen-activated protein kinase is essential in the oxidative stress response and chlamydospore formation in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 2:351-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arana, D. M., C. Nombela, R. Alonso-Monge, and J. Pla. 2005. The Pbs2 MAP kinase kinase is essential for the oxidative-stress response in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Microbiology 151:1033-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ausubel, F. M., et al. (ed.). 1993. Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene Publishing Associates, New York, N.Y.

- 6.Banuett, F. 1998. Signalling in the yeasts: an informational cascade with links to the filamentous fungi. Microbiol. Mol. Biol Rev. 62:249-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boguslawski, G. 1992. PBS2, a yeast gene encoding a putative protein kinase, interacts with the RAS2 pathway and affects osmotic sensitivity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:2425-2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brewster, J. L., T. de Valoir, N. D. Dwyer, E. Winter, and M. C. Gustin. 1993. An osmosensing signal transduction pathway in yeast. Science 259:1760-1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabiscol, E., E. Piulats, P. Echave, E. Herrero, and J. Ros. 2000. Oxidative stress promotes specific protein damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 275:27393-27398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calera, J. A., G. H. Choi, and R. A. Calderone. 1998. Identification of a putative histidine kinase two-component phosphorelay gene (CaHK1) in Candida albicans. Yeast 14:665-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calera, J. A., D. Herman, and R. Calderone. 2000. Identification of YPD1, a gene of Candida albicans which encodes a two-component phosphohistidine intermediate protein. Yeast 16:1053-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calera, J. A., X. J. Zhao, and R. Calderone. 2000. Defective hyphal development and avirulence caused by a deletion of the SSK1 response regulator gene in Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 68:518-525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chauhan, N., D. Inglis, E. Roman, J. Pla, D. Li, J. A. Calera, and R. Calderone. 2003. Candida albicans response regulator gene SSK1 regulates a subset of genes whose functions are associated with cell wall biosynthesis and adaptation to oxidative stress. Eukaryot. Cell 2:1018-1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, H., M. Fujita, Q. Feng, J. Clardy, and G. R. Fink. 2004. Tyrosol is a quorum-sensing molecule in Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:5048-5052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Csank, C., C. Makris, S. Meloche, K. Schröppel, M. Röllinghoff, D. Dignard, D. Y. Thomas, and M. Whiteway. 1997. Derepressed hyphal growth and reduced virulence in a VH1 family-related protein phosphatase mutant of the human pathogen Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 8:2539-2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Csank, C., K. Schröppel, E. Leberer, D. Harcus, O. Mohamed, S. Meloche, D. Y. Thomas, and M. Whiteway. 1998. Roles of the Candida albicans mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog, Cek1p, in hyphal development and systemic candidiasis. Infect. Immun. 66:2713-2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cullen, P. J., W. Sabbagh, Jr., E. Graham, M. M. Irick, E. K. van Olden, C. Neal, J. Delrow, L. Bardwell, and G. F. Sprague, Jr. 2004. A signaling mucin at the head of the Cdc42- and MAPK-dependent filamentous growth pathway in yeast. Genes Dev. 18:1695-1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cullen, P. J., J. Schultz, J. Horecka, B. J. Stevenson, Y. Jigami, and G. F. Sprague, Jr. 2000. Defects in protein glycosylation cause SHO1-dependent activation of a STE12 signaling pathway in yeast. Genetics 155:1005-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Backer, M. D., P. T. Magee, and J. Pla. 2000. Recent developments in molecular genetics of Candida albicans. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:463-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Nadal, E., P. M. Alepuz, and F. Posas. 2002. Dealing with osmostress through MAP kinase activation. EMBO Rep. 3:735-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diez-Orejas, R., G. Molero, F. Navarro-García, J. Pla, C. Nombela, and M. Sánchez-Pérez. 1997. Reduced virulence of Candida albicans MKC1 mutants: a role for a mitogen-activated protein kinase in pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 65:833-837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dominguez, J. M., V. A. Kelly, O. S. Kinsman, M. S. Marriott, F. Gomez de las Heras, and J. J. Martin. 1998. Sordarins: a new class of antifungals with selective inhibition of the protein synthesis elongation cycle in yeasts. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2274-2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du, C., R. Calderone, J. Richert, and D. Li. 2005. Deletion of the SSK1 response regulator gene in Candida albicans contributes to enhanced killing by human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 73:865-871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fonzi, W. A., and M. Y. Irwin. 1993. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 134:717-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia-Rodriguez, L. J., A. Duran, and C. Roncero. 2000. Calcofluor antifungal action depends on chitin and a functional high-osmolarity glycerol response (HOG) pathway: evidence for a physiological role of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae HOG pathway under noninducing conditions. J. Bacteriol. 182:2428-2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerami-Nejad, M., J. Berman, and C. A. Gale. 2001. Cassettes for PCR-mediated construction of green, yellow, and cyan fluorescent protein fusions in Candida albicans. Yeast 18:859-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gillum, A. M., E. Y. H. Tsay, and D. R. Kirsch. 1984. Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyrF mutations. Mol. Gen. Genet. 198:179-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gimeno, C. J., P. O. Ljungdahl, C. A. Styles, and G. R. Fink. 1992. Unipolar cell divisions in the yeast S. cerevisiae lead to filamentous growth: regulation by starvation and RAS. Cell 68:1077-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gustin, M. C., J. Albertyn, M. Alexander, and K. Davenport. 1998. MAP kinase pathways in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1264-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanahan, D. 1988. Techniques for transformation of E. coli, p. 109-135. In D. M. Glover (ed.), DNA cloning. IRL Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 31.Hohmann, S. 2002. Osmotic stress signaling and osmoadaptation in yeasts. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:300-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hornby, J. M., E. C. Jensen, A. D. Lisec, J. J. Tasto, B. Jahnke, R. Shoemaker, P. Dussault, and K. W. Nickerson. 2001. Quorum sensing in the dimorphic fungus Candida albicans is mediated by farnesol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2982-2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jansen, G., F. Buhring, C. P. Hollenberg, and R. M. Ramezani. 2001. Mutations in the SAM domain of STE50 differentially influence the MAPK-mediated pathways for mating, filamentous growth and osmotolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Genet. Genomics 265:102-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang, B., A. F. J. Ram, J. Sheraton, F. M. Klis, and H. Bussey. 1995. Regulation of cell wall beta-glucan assembly: PTC1 negatively affects PBS2 action in a pathway that includes modulation of EXG1 transcription. Mol. Gen. Genet. 248:260-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Justice, M. C., M. J. Hsu, B. Tse, T. Ku, J. Balkovec, D. Schmatz, and J. Nielsen. 1998. Elongation factor 2 as a novel target for selective inhibition of fungal protein synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 273:3148-3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kapteyn, J. C., B. Ter Riet, E. Vink, S. Blad, H. De Nobel, H. van den Ende, and F. M. Klis. 2001. Low external pH induces HOG1-dependent changes in the organization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall. Mol. Microbiol. 39:469-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kobayashi, G. S., and J. E. Cutler. 1998. Candida albicans hyphal formation and virulence: is there a clearly defined role? Trends Microbiol. 6:92-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Köhler, G. A., T. C. White, and N. Agabian. 1997. Overexpression of a cloned IMP dehydrogenase gene of Candida albicans confers resistance to the specific inhibitor mycophenolic acid. J. Bacteriol. 179:2331-2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krems, B., C. Charizanis, and K. D. Entian. 1996. The response regulator-like protein Pos9/Skn7 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is involved in oxidative stress resistance. Curr. Genet. 29:327-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kruppa, M., T. Goins, J. E. Cutler, D. Lowman, D. Williams, N. Chauhan, V. Menon, P. Singh, D. Li, and R. Calderone. 2003. The role of the Candida albicans histidine kinase [CHK1) gene in the regulation of cell wall mannan and glucan biosynthesis. FEMS Yeast Res. 3:289-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kruppa, M., M. A. Jabra-Rizk, T. F. Meiller, and R. Calderone. 2004. The histidine kinases of Candida albicans: regulation of cell wall mannan biosynthesis. FEMS Yeast Res. 4:409-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lay, J., L. K. Henry, J. Clifford, Y. Koltin, C. E. Bulawa, and J. M. Becker. 1998. Altered expression of selectable marker URA3 in gene-disrupted candida albicans strains complicates interpretation of virulence studies. Infect. Immun. 66:5301-5306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leberer, E., D. Harcus, I. D. Broadbent, K. L. Clark, D. Dignard, K. Ziegelbauer, A. Schmidt, N. A. R. Gow, A. J. P. Brown, and D. Y. Thomas. 1996. Signal transduction through homologs of the Ste20p and Ste7p protein kinases can trigger hyphal formation in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13217-13222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee, B. N., and E. A. Elion. 1999. The MAPKKK Ste11 regulates vegetative growth through a kinase cascade of shared signaling components. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12679-12684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee, J., C. Godon, G. Lagniel, D. Spector, J. Garin, J. Labarre, and M. B. Toledano. 1999. Yap1 and Skn7 control two specialized oxidative stress response regulons in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 274:16040-16046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li, S., A. Ault, C. L. Malone, D. Raitt, S. Dean, L. H. Johnston, R. J. Deschenes, and J. S. Fassler. 1998. The yeast histidine protein kinase, Sln1p, mediates phosphotransfer to two response regulators, Ssk1p and Skn7p. EMBO J. 17:6952-6962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li, S., S. Dean, Z. Li, J. Horecka, R. J. Deschenes, and J. S. Fassler. 2002. The eukaryotic two-component histidine kinase Sln1p regulates OCH1 via the transcription factor, Skn7p. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:412-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu, H., J. Köhler, and G. R. Fink. 1994. Suppression of hyphal formation in Candida albicans by mutation of a STE12 homolog. Science 266:1723-1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maeda, T., M. Takekawa, and H. Saito. 1995. Activation of yeast PBS2 MAPKK by MAPKKKs or by binding of an SH3-containing osmosensor. Science 269:554-558X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marles, J. A., S. Dahesh, J. Haynes, B. J. Andrews, and A. R. Davidson. 2004. Protein-protein interaction affinity plays a crucial role in controlling the Sho1p-mediated signal transduction pathway in yeast. Mol. Cell 14:813-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martin, H., J. M. Rodriguez-Pachon, C. Ruiz, C. Nombela, and M. Molina. 2000. Regulatory mechanisms for modulation of signaling through the cell integrity Slt2-mediated pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 275:1511-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martín, H., M. C. Castellanos, R. Cenamor, M. Sánchez, M. Molina, and C. Nombela. 1996. Molecular and functional characterization of a mutant allele of the mitogen-activated protein-kinase gene SLT2(MPK1) rescued from yeast autolytic mutants. Curr. Genet. 29:516-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morgan, B. A., G. R. Banks, W. M. Toone, D. Raitt, S. Kuge, and L. H. Johnston. 1997. The Skn7 response regulator controls gene expression in the oxidative stress response of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 16:1035-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nagahashi, S., T. Mio, N. Ono, T. Yamada-Okabe, M. Arisawa, H. Bussey, and H. Yamada-Okabe. 1998. Isolation of CaSLN1 and CaNIK1, the genes for osmosensing histidine kinase homologues, from the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Microbiology 144:425-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Navarro-García, F., R. Alonso-Monge, H. Rico, J. Pla, R. Sentandreu, and C. Nombela. 1998. A role for the MAP kinase gene MKC1 in cell wall construction and morphological transitions in Candida albicans. Microbiology 144:411-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Navarro-García, F., M. Sanchez, J. Pla, and C. Nombela. 1995. Functional characterization of the MKC1 gene of Candida albicans, which encodes a mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog related to cell integrity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:2197-2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Navarro-García, F., M. Sánchez, C. Nombela, and J. Pla. 2001. Virulence genes in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25:245-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Negredo, A., L. Monteoliva, C. Gil, J. Pla, and C. Nombela. 1997. Cloning, analysis and one-step disruption of the ARG5,6 gene of Candida albicans. Microbiology 143:297-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nelson, B., A. B. Parsons, M. Evangelista, K. Schaefer, K. Kennedy, S. Ritchie, T. L. Petryshen, and C. Boone. 2004. Fus1p interacts with components of the HOG1p mitogen-activated protein kinase and Cdc42p morphogenesis signaling pathways to control cell fusion during yeast mating. Genetics 166:67-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Odds, F. C. 1988. Candida and candidosis. Baillière Tindall, London, United Kingdom.

- 61.Odds, F. C. 1994. Candida species and virulence. ASM News 60:313-318. [Google Scholar]

- 62.O'Rourke, S. M., and I. Herskowitz. 1998. The Hog1 MAPK prevents cross talk between the HOG and pheromone response MAPK pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 12:2874-2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O'Rourke, S. M., and I. Herskowitz. 2002. A third osmosensing branch in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires the Msb2 protein and functions in parallel with the Sho1 branch. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:4739-4749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]