Abstract

We have examined the kinetics of processing of the HIV-1 Gag-Pro-Pol precursor in an in vitro assay with mature protease added in trans. The processing sites were cleaved at different rates to produce distinct intermediates. The initial cleavage occurred at the p2/NC site. Intermediate cleavages occurred at similar rates at the MA/CA and RT/IN sites, and to a lesser extent at sites upstream of RT. Late cleavages occurred at the sites flanking the protease (PR) domain, suggesting sequestering of these sites. We observed paired intermediates indicative of half- cleavage of RT/RH site, suggesting that the RT domain in Gag-Pro-Pol was in a dimeric form under these assay conditions. These results clarify our understanding of the processing kinetics of the Gag-Pro-Pol precursor and suggest regulated cleavage. Our results further suggest that early dimerization of the PR and RT domains may serve as a regulatory element to influence the kinetics of processing within the Pol domain.

Findings

The retroviral protease (PR) processes the Gag and Gag-Pro-Pol precursors during the assembly of the mature virus particle. The viral structural proteins assume altered conformations after processing, and the viral enzymes become fully active in their processed forms [1-7]. Proper proteolytic processing is necessary for assembly of an infectious particle [3,4,8-10].

Cleavage of Gag is ordered and appears to be regulated, at least in part, by the target site sequence, the presence of spacer domains, and the interaction with RNA [8,9,11,12]. Previous studies showed the five HIV-1 Gag processing sites are cleaved at rates that vary up to 400-fold in vitro [9,13]. Initial cleavage occurs at the p2/NC site followed by an intermediate rate of cleavage at the MA/CA and p1/p6 sites, and final cleavage at the CA/p2 and NC/p1 sites [9,12-16]. A similar pattern of ordered processing appears to occur in infected cells [9,12,17,18].

Processing of the HIV-1 Gag-Pro-Pol precursor by protease in trans is less studied, although the final cleavage products [MA, CA, NC, transframe (TF), PR, RT, IN] are well characterized [19-22]. The HIV-1 Gag-Pro-Pol precursor results from a -1 frameshift event during translation at a site near the 3' end of the gag reading frame to join the gag and pro-pol reading frames [23,24]. For this study, we created by site-directed mutagenesis [25,26] a continuous HIV-1 gag-pro-pol reading frame that would produce a full-length precursor identical in sequence to the viral Gag-Pro-Pol polyprotein precursor [23,27] (Fig. 1A). Intrinsic protease activity was inactivated by a D25A substitution of the catalytic aspartate of the PR domain to produce the final construct GPPfs-PR (Fig. 1A). We expressed the radio-labeled Gag-Pro-Pol using an in vitro transcription/translation strategy [9,28] and monitored cleavage at known processing sites as a function of time after adding 0.25 μg recombinant HIV-1 protease (as described in [13,28,29]) in a reaction volume of 50 μl. Under these conditions the concentration of precursor is approximately 0.1 nM. Products were separated using two different SDS-PAGE systems [30,31] prior to autoradiography.

Figure 1.

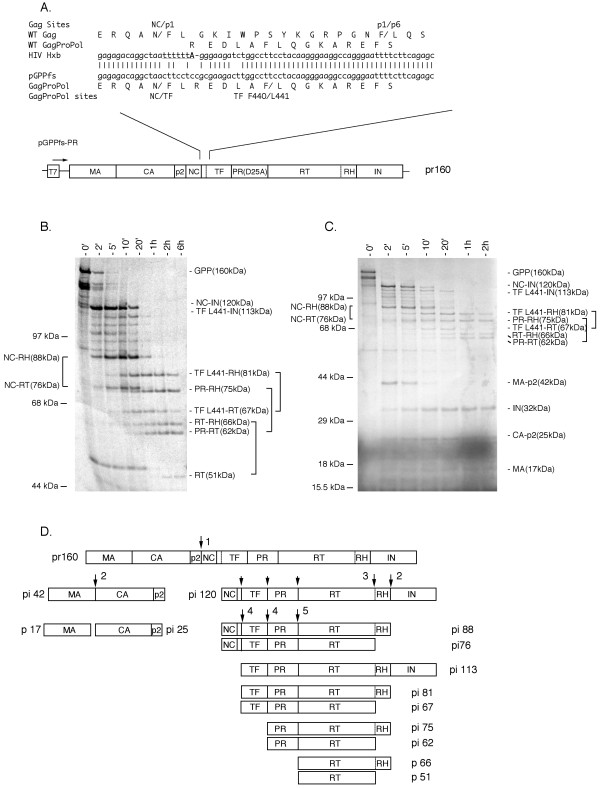

A. The frameshift mutation in pGPPfs-PR. Above: the sequence of wild type HIV-1 HXB (GenBank:NC001802) molecular clone in the area of translational frameshift in gag-pro-pol is shown. The heptanucleotide slippery sequence required for translational frameshifting is underlined [23, 24]. The adenine that is read twice during frameshifting is shown in bold. The exact site of frameshifting in the wild type virus is variable with 70% of Gag-Pro-Pol product containing Leu as the second residue of the transframe domain (TF) [27]. pGPPfs-PR expressed in vitro in a coupled transcription/translation system [28] gives the predominant Gag-Pro-Pol product. Additional translationally silent substitutions were inserted in the area frameshift to reduce secondary structure and translational pausing during expression. The activity of the intrinsic protease was inactivated by a D25A substitution of the catalytic aspartate. The location of the Gag NC/p1 [53] and pl/p6 [54] sites and the Gag-Pro-Pol NC/TF and TF F440/L441 sites [28, 32, 33, 35] are also shown. Below: an overall schematic pGPPfs-PR. B, C. Processing of the HIV-1 Gag-Pro-Pol precursor in vitro showing the kinetics of processing and the generation of product pairs over time. The full-length Gag-Pro-Pol pr160 precursor containing an inactive protease (by PR D25A mutation of the catalytic aspartate) was generated by transcription and translation of pGPPfs-PR in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate. Purified mature HIV-1 protease was added in trans following the 0' timepoint. Aliquots were removed at the indicated time and the protein products separated by Tris-Glycine SDS-PAGE (B) [30] or by Tris-Tricine SDS-PAGE (C) [31]. Paired products resulting from prior removal of IN followed by partial cleavage at the RT/RH site are denoted with brackets. Molecular mass markers are shown on the left. The molecular masses of the intermediates and final products, as estimated from published sequence or common nomenclature, are also shown. Products are represented in abbreviated form by the N- and C-terminal domains according to the nomenclature of Leis et al. [55]. D. Proposed pathway for the ordered processing of the HIV-1 Gag-Pro-Pol precursor by protease in trans. The Gag-Pro-Pol precursor and the observed predominant processing intermediates are represented as boxes with processing sites denoted as vertical lines. The schematic separates the observed Gag-Pro-Pol cleavages into distinct rates. The initial cleavage at p2/NC is shown with a large arrow and labeled 1. The next cleavages occur with similar rates and are labeled 2 (RH/IN and MA/CA). This cleavage is quickly followed by half-cleavage at the RT/RH site (labeled 3). A series of intermediates between 120 kDa and 88 kDa are accounted for at least in part by early cleavage at the sites upstream of RT (TF F440/L441, TF/PR, PR/RT), and these are indicated with small arrows. The slower cleavages at these sites (labeled 4 and 5) give rise to the later paired products. The molecular masses shown of the intermediates and final products were estimated from published sequence or common nomenclature.

Fig. 1B and 1C show the pattern of cleavage products generated at different time points after the addition of protease in trans. We identified over ten distinct species greater than 50 kDa (Fig 1B). Fig. 1C shows products of lower molecular mass [31]. The combination of two different gel systems allowed for the separation and analysis of the appearance of each product. An initial species of 120 kDa (processing intermediate pi120) was rapidly generated within 2 minutes then disappeared to form distinct intermediates of 88, 81, 76, 75, 67, 62 kDa, and finally the mature RT products p66 and p51 (Fig. 1B, C). We observed a large difference in the rates of appearance of these intermediates. After 6 hours of incubation six processing intermediates remained even though the first cleavage event to generate pi120 occurred within 2 min (Fig 1B), indicating that the sites are cleaved at highly different rates. No observable processing occurred without added protease (data not shown), indicating that processing was due to the added protease. Thus, processing of the Gag-Pro-Pol precursor results in a processing cascade consisting of discrete intermediates.

We have used three strategies to assign the cleavage sites that define the ends of the processing products. The first we assigned the products based on the known processing sites in Gag-Pro-Pol. The size of the pi120 intermediate was consistent with an initial cleavage at the p2/NC site, the same site initially cleaved in the Gag precursor [9,14-16]. Second, we truncated the Gag-Pro-Pol precursor to establish the polarity of the initial cleavage site. We implicated cleavage at the p2/NC site by truncating 116 residues from the C-terminal end of the precursor via linearization of the template by Afl II prior to RNA synthesis in vitro. Protease cleavage of the truncated precursor resulted in a shift of the pi120 intermediate to 110 kDa (data not shown), a size consistent with initial cleavage at the p2/NC site. Third, in order to confirm the site of cleavage and the identification of products we blocked individually blocked cleavage at the p2/NC, TF/PR, PR/RT, RT/RH and RH/IN sites by site-directed mutagenesis as described (data not shown) [9,13]. Each blocking mutation resulted in alternative unprocessed intermediates with a molecular mass consistent with an absence of cleavage at the mutated site. Thus, this approach supported the identification of the cleavage sites and the intermediates presented here. We noted that each site was generally cleaved independently of the other sites by protease in trans. A notable exception was the CA/p2 site which showed enhanced cleavage when the earlier cleaved p2/NC site was blocked (M377I mutation). Previously, we reported similar enhanced cleavage of this site in the Gag precursor with the same blocking mutation at the p2/NC site [9]. There is a series of faint minor products between pi120 and pi88, at 113 kDa, 107 kDa, 100 kDa, and 95 kDa (Fig. 2A) seen at the 2-minute time point. These likely represent a low level of cleavage at all of the known cleavage sites upstream of RT early in the processing cascade. We showed by mutagenesis that 113 kDa intermediate resulted from cleavage at the TF F440/L441 site (Fig. 1A, and 1D) rather than cleavage at the NC/TF (data not shown). The TF F440/L441 site has previously been identified as a processing site by others [32-34] using less than full length Pol precursors, and this site is cleaved by the activated PR within full length Gag-Pro-Pol [17,28,35,36]. Other intermediates in this group are likely accounted for as PR-IN (107 kDa) and RT-IN (97 kDa) products.

We observed four sets of paired intermediates and products (denoted by brackets in Fig. 1B, C). We interpret these pairs to represent intermediates that resulted from full cleavage at the RH/IN site followed by half cleavage at the RT/RH site. Numerous studies have shown that partial cleavage of the RT/RH site in the purified RT-RH homodimer is dependent on the dimerization of the RT domain to induce unfolding of a single RH domain [19,21,22,37-40]. We observed a similar pattern with the full length Gag-Pro-Pol precursor, with IN removed prior to half cleavage of the RT/RH cleavage site, also in agreement with [41] where an E. coli based expression system was used. Thus, by analogy with the results of others, we infer that the RT domain within the expressed Gag-Pro-Pol precursor is dimeric either prior to or immediately after removal of IN. The pi88/pi76 paired products, derived from pi120, appeared initially at the 2 minute time point showing that RH/IN and RT/RH cleavage occur relatively early in the processing cascade. The later and overlapping appearance of the three remaining product pairs showed that subsequent N-terminal processing of the pi88/pi76 pair is ordered, but occurs at more similar rates. The SDS-PAGE system utilized in Fig. 1B allows for separation of the pi76 and pi75 intermediates and shows the disappearance of the pi88/pi76 paired products follows the 20 minute time point. The pi81/pi67 and pi75/pi62 pairs represent later products that likely result from cleavage at the TF F440/L441 and TF/PR sites, respectively. Lastly, the mature p66/p51 products represent final cleavage at the PR/RT site.

Initial cleavage at the p2/NC site also generated a MA-CA-p2 (pi42) product (Fig. 1C). We previously showed that cleavage of p42 in vitro occurs at the MA/CA cleavage site followed by slower cleavage at the CA/p2 site [9,13]. We observe here that the rates of processing of the MA/CA and RH/IN sites are similar as shown by the similar appearance of pi25 CA-p2 and p32 IN (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1D summarizes a proposed cascade for processing of Gag-Pro-Pol by mature protease in trans. The initial cleavage occurs at the p2/NC site (presumably at the same rate this site is cleaved in Gag), generating the pi120 NC-TF-PR-RT-RH-IN intermediate and the p42 MA-CA-p2 intermediate. The next cleavage removes IN from the C terminus of pi120 by cleavage at RH/IN producing pi88. Removal of IN occurs at a rate similar to cleavage between MA-CA. Cleavage of RH/IN is closely followed by cleavage of the RT/RH site to generate the initial paired pi88 and pi76 NC-TF-PR-RT (RH) products. The presence of these paired products suggests that dimerization of the RT-containing processing intermediate occurred early in the processing cascade, consistent with the results of others who observed a similar cleavage pattern using more fully processed dimeric RT [22,38,40]. Processing at the TF F440/L441 and TF/PR occur next followed by the final cleavage between PR/RT to generate the final mature PR and RT products. Final cleavage of the precursor occurs in the sites flanking the PR domain, suggesting that accessibility to these sites may be restricted via formation of a dimer interface structure similar to that observed in mature protease [42].

The overall pattern and extent of processing differs substantially with protease present in trans compared to the pattern seen with the protease embedded in the precursor, as previously characterized [28,35,36]. Cleavage of the Gag-Pro-Pol precursor by the embedded protease appears to be much more restrictive with cleavages only observed at the p2/NC site and the TF F440/L441 sites. We show here that protease present in trans cleaves all of the Gag-Pro-Pol sites but at varying rates (Figs. 1B, C, D), resulting in a processing cascade. One possibility is that the embedded protease shows restricted site selection due to its location within the precursor.

We infer that the Gag-Pro-Pol precursor was able to dimerize in this expression system. The state of the Gag-Pro-Pol precursor in newly assembled (or assembling) virions could differ. In infected cells, Gag-Pro-Pol may dimerize while moving to the assembly site [43-46] or during assembly, affecting the kinetics of precursor processing. Alternatively, dimerization of Gag-Pro-Pol monomer may be constrained by the excess of Gag during assembly, as suggested by others [47-49]. In that case, the presence of Gag could limit Gag-Pro-Pol dimerization by forming heterodimers, in turn altering the kinetic of processing. These considerations are not mutually exclusive. One of the early cleavage events detailed here (such as cleavage at p2/NC) could also release a truncated precursor from a Gag/Gag-Pro-Pol heterodimer and permit rapid dimerization of the PR and RT domains.

The other feature of the system we have used is the reliance of protease cleavages in trans. Use of trans protease on the full length precursor allows for the clear evaluation of generation of each product, however, this approach is unable to discern the possible cleavage of nascent or truncated products or the effect of an active embedded protease. Expression of Gag-Pro-Pol in vitro with an unmutated protease domain results in rapid autocatalytic cleavage at the p2/NC site and the TF F440/L441 site to produce the 113 KDa intermediate [28,35]. Immediate dimerization in cells of the full length precursor would likely result in premature cleavage [50-52]. Thus, in the context of budding virions there may be an interplay between monomeric versus dimeric Gag-Pro-Pol as substrate, and embedded versus free protease for cleavage. The extent to which these different combinations may alter the order of cleavage and the successful assembly of virus is not known.

We show here that cleavage of the Gag-Pro-Pol processing sites by trans protease occurs at different rates, and we suggest that cleavage is likely regulated, in part, by the dimerization of the protease and RT domains. We and others have shown that timed and ordered cleavage of the HIV-1 Gag precursors is highly regulated and is necessary for the production of an infectious, properly assembled virion. We do not yet know the extent of the requirement for timed cleavage of Gag-Pro-Pol in producing infectious virus. Characterization of the ordered cleavage of Gag-Pro-Pol furthers our understanding of HIV-1 precursor processing and suggests further mechanisms at work in the regulation of HIV-1 assembly.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JL and SP carried out the experiments. RS and SP drafted the manuscripts and designed the experiments. AK provided helpful discussion and editing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by NIH grants R01-AI50485 (to RS) and R01-GM66681 (to AK) in addition to support from the UNC Center For AIDS Research (P30-AI50410).

Contributor Information

Steve C Pettit, Email: stpettit@yahoo.com.

Jeffrey N Lindquist, Email: jlindquist@ucsd.edu.

Andrew H Kaplan, Email: akaplan@med.unc.edu.

Ronald Swanstrom, Email: risunc@med.unc.edu.

References

- Craven RC, Bennett RP, Wills JW. Role of the avian retroviral protease in the activation of reverse transcriptase during virion assembly. J Virol. 1991;65:6205–6217. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6205-6217.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart L, Vogt VM. Reverse transcriptase and protease activities of avian leukosis virus Gag-Pol fusion proteins expressed in insect cells. J Virol. 1993;67:7582–7596. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7582-7596.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanstrom R, Wills J. Retroviral gene expression: Synthsis, processing, and assembly of viral proteins. In: Varmus HE, Coffin JM and Hughes SH, editor. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor, NY, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 263–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Ridky TW, Krishna NK, Leis J. Altered Rous sarcoma virus Gag polyprotein processing and its effects on particle formation. J Virol. 1997;71:2083–2091. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2083-2091.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross I, Hohenberg H, Wilk T, Wiegers K, Grattinger M, Muller B, Fuller S, Krausslich HG. A conformational switch controlling HIV-1 morphogenesis. Embo J. 2000;19:103–113. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi SM, Vogt VM. Role of the Rous sarcoma virus p10 domain in shape determination of gag virus-like particles assembled in vitro and within Escherichia coli. J Virol. 2000;74:10260–10268. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.21.10260-10268.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandhagopal N, Simpson AA, Johnson MC, Francisco AB, Schatz GW, Rossmann MG, Vogt VM. Dimeric rous sarcoma virus capsid protein structure relevant to immature Gag assembly. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven RC, Leure PA, Erdie CR, Wilson CB, Wills JW. Necessity of the spacer peptide between CA and NC in the Rous sarcoma virus gag protein. J Virol. 1993;67:6246–6252. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6246-6252.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit SC, Moody MD, Wehbie RS, Kaplan AH, Nantermet PV, Klein CA, Swanstrom R. The p2 domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag regulates sequential proteolytic processing and is required to produce fully infectious virions. J Virol. 1994;68:8017–8027. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8017-8027.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt VM. Proteolytic processing and particle maturation. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;214:95–131. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80145-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng N, Pettit SC, Tritch RJ, Ozturk DH, Rayner MM, Swanstrom R, Erickson VS. Determinants of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 p15NC-RNA interaction that affect enhanced cleavage by the viral protease. J Virol. 1997;71:5723–5732. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5723-5732.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegers K, Rutter G, Kottler H, Tessmer U, Hohenberg H, Krausslich HG. Sequential steps in human immunodeficiency virus particle maturation revealed by alterations of individual Gag polyprotein cleavage sites. J Virol. 1998;72:2846–2854. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2846-2854.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit SC, Henderson GJ, Schiffer CA, Swanstrom R. Replacement of the P1 amino acid of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag processing sites can inhibit or enhance the rate of cleavage by the viral protease. J Virol. 2002;76:10226–10233. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10226-10233.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mervis RJ, Ahmad N, Lillehoj EP, Raum MG, Salazar FH, Chan HW, Venkatesan S. The gag gene products of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: alignment within the gag open reading frame, identification of posttranslational modifications, and evidence for alternative gag precursors. J Virol. 1988;62:3993–4002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.11.3993-4002.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowda S, Stein B, Engleman E. Identification of protein intermediates in the processing of the p55 HIV-1 Gag precursor in cells infected with recombinant vaccinia virus. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:8459–8462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krausslich HG, Ingraham RH, Skoog MT, Wimmer E, Pallai PV, Carter CA. Activity of purified biosynthetic proteinase of human immunodeficiency virus on natural substrates and synthetic peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:807–811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.3.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhofer H, von der Helm K, Nitschko H. In vivo processing of Pr160gag-pol from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV) in acutely infected, cultured human T-lymphocytes. Virology. 1995;214:624–627. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almog N, Roller R, Arad G, Passi EL, Wainberg MA, Kotler M. A p6Pol-protease fusion protein is present in mature particles of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1996;70:7228–7232. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7228-7232.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronese FD, Copeland TD, DeVico AL, Rahman R, Oroszlan S, Gallo RC, Sarngadharan MG. Characterization of highly immunogenic p66/51 as the reverse transcriptase of HTLV-III/LAV. Science. 1986;231:1289–1291. doi: 10.1126/science.2418504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland TD, Oroszlan S. Genetic locus, primary structure, and chemical synthesis human immunodeficiency virus protease. Gene Anal Tech. 1988;5:109–115. doi: 10.1016/0735-0651(88)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay D, Evans DB, Deibel MR, Vosters AF, Eckenrode FM, Einspahr HM, Hui JO, Tomasselli AG, Zurcherneely HA, Heinrikson RL, Sharma SK. Purification and Characterization of Heterodimeric Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type-1 (HIV-1) Reverse Transcriptase Produced by Invitro Processing of P66 with Recombinant HIV-1 Protease. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14227–14232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasselli AG, Sarcich JL, Barrett LJ, Reardon IM, Howe WJ, Evans DB, Sharma SK, Heinrikson RL. Human immunodeficiency virus type-1 reverse transcriptase and ribonuclease H as substrates of the viral protease. Protein Sci. 1993;2:2167–2176. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560021216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks T, Power MD, Maslarz FR, Luciw PA, Barr PJ, Varmus HE. Characterization of ribosomal frame-shifting in HIV-1 gag/pol expression. Nature. 1988;331:280–283. doi: 10.1038/331280a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reil H, Kollmus H, Weidle UH, Hauser H. A heptanucleotide sequence mediates ribosomal frameshifting in mammalian cells. J Virol. 1993;67:5579–5584. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5579-5584.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebenek K, Kunkel TA. The use of native T7 DNA polymerase for site-directed mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:5408. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.13.5408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel TA, Bebenek K, McClary J. Efficient site-directed mutagenesis using uracil-containing DNA. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:125–139. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick RJ, Henderson LE. Part III: Analyses. In: Myers G, Korber B, Wain-Hobson S, Jeang KT, Henderson L and Pavlakis G, editor. Human Retroviruses and AIDS. Los Alamos, NM, The Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1994. pp. 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit SC, Gulnik S, Everitt L, Kaplan AH. The dimer interfaces of protease and extra-protease domains influence the activation of protease and the specificity of GagPol cleavage. J Virol. 2003;77:366–374. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.366-374.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody MD, Pettit SC, Shao W, Everitt L, Loeb DD, Hutchison C, Swanstrom R. A side chain at position 48 of the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 protease flap provides an additional specificity determinant. Virology. 1995;207:475–485. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacterophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;277:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schagger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phylip LH, Griffiths JT, Mills JS, Graves MC, Dunn BM, Kay J. Activities of precursor and tethered dimer forms of HIV proteinase. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;362:467–472. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1871-6_61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis JM, Dyda F, Nashed NT, Kimmel AR, Davies DR. Hydrophilic peptides derived from the transframe region of Gag-Pol inhibit the HIV-1 protease. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2105–2110. doi: 10.1021/bi972059x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Morag A, Almog N, Blumenzweig I, Dreazin O, Kotler M. Extended nucleocapsid protein is cleaved from the Gag-Pol precursor of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:581–590. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-3-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit S, Everitt L, Choudhury S, Dunn BM, Kaplan AH. Initial cleavage of the HIV-1 GagPol precursor by its activated protease occurs by an intramolecular mechanism. J Virol. 2004;78:8477–8485. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8477-8485.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit SC, Clemente JC, Jeung JA, Dunn BM, Kaplan AH. Ordered processing of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 GagPol precursor is influenced by the context of the embedded viral protease. J Virol. 2005;79:10601–10607. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10601-10607.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoote MM, Colisan JE, Folks TM, Fauci AS, Martin MA, Venkatesan S. Structural characterization of reverse transcriptase and endonuclease polypeptides of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome retrovirus. J Virol. 1986;60:771–775. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.2.771-775.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goobar-Larsson L, Backbro K, Unge T, Bhikhabhai R, Vrang L, Zhang H, Orvell C, Strandberg B, Oberg B. Disruption of a salt bridge between Asp 488 and Lys 465 in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase alters its proteolytic processing and polymerase activity. Virology. 1993;196:731–738. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Smerdon SJ, Jager J, Kohlstaedt LA, Rice PA, Friedman JM, Steitz TA. Structural basis of asymmetry in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase heterodimer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7242–7246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro JM, Damier L, Boretto J, Priet S, Canard B, Querat G, Sire J. Glutamic residue 438 within the protease-sensitive subdomain of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase is critical for heterodimer processing in viral particles. Virology. 2001;290:300–308. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluis-Cremer N, Arion D, Abram ME, Parniak MA. Proteolytic processing of an HIV-1 pol polyprotein precursor: insights into the mechanism of reverse transcriptase p66/p51 heterodimer formation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1836–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber IT. Comparison of the crystal structures and intersubunit interactions of human immunodeficiency and Rous sarcoma virus proteases. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10492–10496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MK, Hooker CW, Harrich D, Crowe SM, Mak J. Gag-Pol supplied in trans is efficiently packaged and supports viral function in human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2001;75:6835–6840. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.6835-6840.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CA. Tsg101: HIV-1's ticket to ride. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:203–205. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(02)02350-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff A, Ehrlich LS, Cohen SN, Carter CA. Tsg101 control of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag trafficking and release. J Virol. 2003;77:9173–9182. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9173-9182.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono A, Freed EO. Cell-type-dependent targeting of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly to the plasma membrane and the multivesicular body. J Virol. 2004;78:1552–1563. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1552-1563.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Morrow CD. Overexpression of the gag-pol precursor from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral genomes results in efficient proteolytic processing in the absence of virion production. J Virol. 1991;65:5111–5117. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.5111-5117.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karacostas V, Wolffe EJ, Nagashima K, Gonda MA, Moss B. Overexpression of the HIV-1 gag-pol polyprotein results in intracellular activation of HIV-1 protease and inhibition of assembly and budding of virus-like particles. Virology. 1993;193:661–671. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halwani R, Khorchid A, Cen S, Kleiman L. Rapid localization of Gag/GagPol complexes to detergent-resistant membrane during the assembly of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2003;77:3973–3984. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.7.3973-3984.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krausslich HG. Human immunodeficiency virus proteinase dimer as component of the viral polyprotein prevents particle assembly and viral infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3213–3217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krausslich HG. Specific inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus proteinase prevents the cytotoxic effects of a single-chain proteinase dimer and restores particle formation. J Virol. 1992;66:567–572. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.567-572.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatlin J, Arrigo SJ, Schmidt MG. Regulation of intracellular human immunodeficiency virus type-1 protease activity. Virology. 1998;244:87–96. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wondrak EM, Louis JM, de RH, Chermann JC, Roques BP. The gag precursor contains a specific HIV-1 protease cleavage site between the NC (P7) and P1 proteins. Febs Letters. 1993;333:21–24. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson LE, Sowder RC, Copeland TD, Oroszlan S, Benveniste RE. Gag precursors of HIV and SIV are cleaved into six proteins found in the mature virions. J Med Primatol. 1990;19:411–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leis J, Baltimore D, Bishop JM, Coffin J, Fleissner E, Goff SP, Oroszlan S, Robinson H, Skalka AM, Temin HM, Vogt VM. Standardized and simplified nomenclature for proteins common to all retroviruses. J Virol. 1988;62:1808–1809. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.5.1808-1809.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]