Abstract

Plant morphology is dramatically influenced by environmental signals. The growth and development of the root system is an excellent example of this developmental plasticity. Both the number and placement of lateral roots are highly responsive to nutritional cues. This indicates that there must be a signal transduction pathway that interprets complex environmental conditions and makes the “decision” to form a lateral root at a particular time and place. Lateral roots originate from differentiated cells in adult tissues. These cells must reenter the cell cycle, proliferate, and redifferentiate to produce all of the cell types that make up a new organ. Almost nothing is known about how lateral root initiation is regulated or coordinated with growth conditions. Here, we report a novel growth assay that allows this regulatory mechanism to be dissected in Arabidopsis. When Arabidopsis seedlings are grown on nutrient media with a high sucrose to nitrogen ratio, lateral root initiation is dramatically repressed. Auxin localization appears to be a key factor in this nutrient-mediated repression of lateral root initiation. We have isolated a mutant, lateral root initiation 1 (lin1), that overcomes the repressive conditions. This mutant produces a highly branched root system on media with high sucrose to nitrogen ratios. The lin1 phenotype is specific to these growth conditions, suggesting that the lin1 gene is involved in coordinating lateral root initiation with nutritional cues. Therefore, these studies provide novel insights into the mechanisms that regulate the earliest steps in lateral root initiation and that coordinate plant development with the environment.

The development of a plant from a newly germinated seedling represents a phenomenal transformation. Nearly all the structures that comprise the plant body are added postembryonically. During vegetative plant growth, a population of meristematic stem cells at the shoot tip divides continuously to regenerate itself and produce stems, leaves, and flowers. A similar population of cells at the root tip is responsible for root growth. In addition, certain shoot and root cells can be activated to produce new shoots and roots, each with a new meristem at its tip. The number and location of organs is not predetermined in plant development; therefore, each plant can integrate information from its environment into the decisions it makes about root and shoot formation. This dynamic developmental strategy provides a clear advantage for a nonmotile organism. Plants are completely dependent on the resources that are available in their immediate vicinity. Unfortunately, nutrient availability and distribution are in constant flux in the environment. Plants must be able to sense these changes and respond appropriately. The presence of active stem cell populations and the ability to generate new ones allows the plant to adapt its morphology to its unique and changeable environment.

A prime example of the developmental plasticity described above is lateral root formation in the root system. Lateral root placement is dramatically influenced by external cues (Leyser and Fitter, 1998). This is perhaps not surprising because the development of an optimal root system is a key factor in a plant's ability to survive adverse conditions (Atkinson and Hooker, 1993). In particular, the availability of nutrients affects both the number and location of lateral root initiation sites (Drew et al., 1973; Drew, 1975; Drew and Saker, 1978). Plants sense the level of nutrients in the soil directly via external sensors, and also monitor and respond to their own internal nutrient status. Based on this information, plants must decide whether or not to trigger lateral root initiation. Hence, the formation of lateral roots in the root system provides a good model for studying how plant development is coordinated with environmental conditions.

Lateral roots originate from mature, nondividing pericycle cells within the parent root. Pericycle cells are unique in that they are arrested in the G2 phase of the cell cycle (Beeckman et al., 2001). Some unknown signal triggers groups of pericycle cells to reenter the cell cycle and become lateral root founder cells. The founder cells undergo a well-defined program of oriented cell divisions and produce a patterned lateral root primordium containing all the differentiated cell types of a mature root (Charleton, 1991; Malamy and Benfey, 1997a). The primordium then enlarges through the parent tissues, develops a meristem at the tip, and begins to grow as a mature lateral root (Malamy and Benfey, 1997a). While this process is under way, the neighboring cells remain quiescent and maintain the integrity of the parent root. Radially, the pericycle-derived founder cells are always located opposite to the xylem poles of the parent root. In Arabidposis, the pericycle cells in this position are marked by expression of CyclinA2 (Beeckman et al., 2001). In contrast, it is difficult to predict when and where new lateral root primordia will form longitudinally along the parent root (Torrey, 1986; Charleton, 1991).

The first visible event in lateral root initiation is a series of anticlinal divisions in the root pericycle (Charleton, 1991; Malamy and Benfey, 1997b). However, the critical decisions about where and when a lateral root will form must occur before cell divisions become visible. The very early events that commit pericycle cells to the lateral root program but precede the first cell divisions remain a mystery. Many studies have suggested that specific pericycle cells gain competency to become founder cells and complete the first rounds of cell division soon after they are produced at the root tip, even though lateral root primordia are not visible until some time later (Torrey, 1986; Dubrovsky et al., 2000). This suggests that environmental conditions that influence lateral root number may act by determining the number of preselected pericycle cells at the growing tip. However, not all preselected cells go on to become lateral root primordia (Dubrovsky et al., 2000). Furthermore, exogenous application of the plant hormone auxin to mature regions of the root can stimulate excess lateral root formation (Charleton, 1991), suggesting that even cells that were not preselected are capable of being recruited to the lateral root program. Therefore, there are multiple steps preceding visible lateral root initiation that may be subject to regulation by environmental cues.

The plant hormone auxin appears to play a critical role in lateral root initiation. Exogenous application of auxin stimulates lateral root formation (Evans et al., 1994) and some auxin-resistant mutants have reduced numbers of lateral roots (Malamy and Benfey, 1997b; for review, see Hobbie, 1998). Furthermore, mutants that accumulate auxin to high levels produce excess lateral roots (Boerjan et al., 1995; King et al., 1995; Delarue et al., 1998). It is believed that auxin is produced in young aerial tissues and transported in a polar fashion from the shoot system to the root to induce lateral root formation. The strongest support for this mechanism is that chemical inhibitors of polar auxin transport completely inhibit lateral root initiation (Reed et al., 1998). How auxin movement or activity interacts with environmental signals to appropriately modulate lateral root initiation is at present unknown.

Despite considerable efforts, there are only two reported mutants that are specifically affected in lateral root initiation. Both aberrant lateral root formation (alf) 4 and solitary root (slr) fail to initiate lateral roots and neither are rescued by auxin application (Celenza et al., 1995; Fukaki et al., 2001). ALF4 has been cloned and encodes a large protein of unknown function (DiDonato et al., 2001). SLR encodes IAA14, a member of the large family of transcription factors that are believed to mediate specific responses to auxins (Fukaki et al., 2001). It is unknown how either of these genes function in lateral root initiation or how their activity is influenced by environmental cues.

We would like to understand how lateral root initiation is regulated. In particular, our objective is to identify the molecular mechanisms that determine when and where a new lateral root will form, and ask how these mechanisms are coordinated with environmental conditions. We have taken a novel approach to accomplish this goal. Mutants that fail to form lateral roots at all are apparently rare, indicating that the genes regulating this process may be either redundant or essential. In contrast, mutants with slightly increased or decreased numbers of lateral roots are difficult to identify because even isogenic seedlings show high variability in lateral root initiation (J.E. Malamy, unpublished data). Therefore, we set out to define growth conditions where lateral root initiation levels are consistent and predictable. These studies resulted in the definition of a nutrient media that severely represses lateral root initiation. Once established, this assay allowed us to identify genetic and physiological factors that are essential for the coordination of lateral root initiation with environmental cues. The identification of a novel lateral root initiation mutant, lin1, provides the first insight into the molecular regulation of the decision making pathways that lead to lateral root production.

RESULTS

Lateral Root Initiation Is Repressed by a High Suc to Nitrogen Ratio in the Growth Media

To create a screen for mutants that mis-regulate lateral root initiation, we needed to find growth conditions where lateral root initiation levels are consistent and predictable. Therefore, we germinated Arabidopsis (ecotype Columbia [Col]) seedlings on various nutrient media and examined 13-d-old seedlings microscopically to determine the number of lateral roots and lateral root primordia (see “Materials and Methods”). Significantly, we found that seedlings grown on media containing 4.5% (w/v) Suc and 0.02 mm nitrogen (in the form of NH4NO3) produce hardly any lateral roots or lateral root primordia by 13 d post-germination. A representative experiment is shown in Table I. There is some variability in this response, but seedlings grown on 4.5% (w/v) Suc and 0.02 mm nitrogen always produced less than one-half the number of lateral roots observed on commercial Murashige and Skoog media (Gibco-BRL) with 4.5% (w/v) Suc. Although plant roots were shorter on 0.02 mm nitrogen, the reduced length was not sufficient to account for the reduction in lateral root number (Table I). (For convenience, we will refer to the various media as % Suc/[N]. 4.5/0.02 represents the repressive media. Commercial Murashige and Skoog media is designated 4.5/60 because it contains 60 mm nitrogen supplied as 20 mm NH4NO3 and 20 mm KNO3.)

Table I.

Lateral root initiation in response to varying Suc to nitrogen ratios

| % Suc | [N]a | Lateral Rootsb | Lengthc | Lateral Roots |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm | cm | |||

| 4.5 | 0.02 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 3.04 ± 0.39 | 0.33 |

| 4.5 | 60.0d | 16.6 ± 4.2 | 4.46 ± 0.56 | 3.72 |

| 0.5 | 0.02 | 19.7 ± 5.1 | 3.82 ± 0.40 | 5.16 |

The sole nitrogen source in the media is NH4NO3. NH4NO3 (0.01 mm) is referred to as 0.02 mm N.

Lateral roots, including both microscopic lateral root primordia and emerged lateral roots, were counted on 13-d-old seedlings. Means ± sd are given for 10 to 14 roots.

Root length was measured from hypocotyl/root junction. Means ± sd are given for 25 to 30 roots.

Standard Murashige and Skoog media (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY), which contains 20 mm NH4NO3 and 20 mm KN03 for a total of 60 mm N.

Because plant shoot systems are severely stunted under the low nitrogen conditions, we were concerned that the lack of lateral root initiation was a secondary affect of overall nitrogen starvation. However, reducing the Suc concentration to 0.5% (w/v) while maintaining the low nitrogen concentration in the media restored lateral root initiation to the levels seen with high levels of nitrogen (Table I). Further analysis confirmed that either reducing the Suc levels or increasing the nitrogen levels gradually increased lateral root initiation (not shown). Therefore, we conclude that the ratio of Suc to nitrogen is a key factor in regulating lateral root initiation in this assay.

Arabidopsis seedlings must interpret the high Suc to nitrogen ratio as a cue to repress lateral root initiation, either by sensing the external environment directly or by monitoring internal nutrient status and/or metabolic activities. Growing seedlings on Suc-containing media in sealed petri dishes does not resemble any natural field conditions, and is expected to have many complex effects on plant metabolism. Therefore, it is difficult to guess what component of our assay conditions provides the critical cue that represses lateral root initiation. Nevertheless, our results clearly indicate that plants possess a mechanism for regulating lateral root initiation in response to nutritional cues. Our growth conditions provide a convenient assay for dissecting this regulatory mechanism and finding mutations in key regulatory genes.

Identification of lin1, a Mutant in the Regulation of Lateral Root Initiation

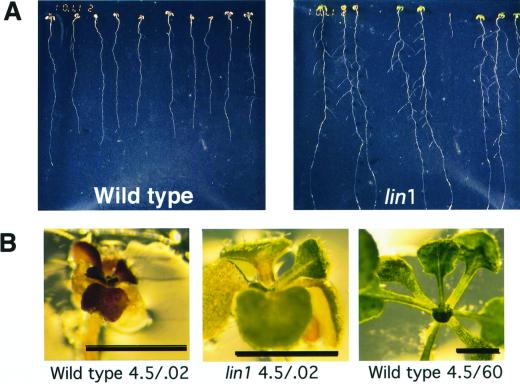

We took advantage of the consistently low numbers of lateral roots initiated when plants are grown on media with a high Suc to nitrogen ratio to screen for mutants. We reasoned that seedlings interpret the 4.5/0.02 media as a growth condition in which lateral root initiation must be repressed. Therefore, a mutation in a critical gene in this decision-making pathway should permit plants to overcome repression. One thousand ethyl methanesulfonate-mutagenized Arabidopsis seeds (ecotype Col) were planted on the repressive 4.5/0.02 media and allowed to grow for 7 to 10 d. To facilitate screening, the primary root tips were then cut off and the plants allowed to grow for an additional 7 d. Cutting off the primary root tips causes most lateral root primordia to develop and emerge rapidly from the parent root; therefore, the resulting lateral roots are visible without microscopic analysis. Putative mutants were selected that produced four or more visible lateral roots under this treatment regime. These plants were transferred to standard growth media to recover and eventually transplanted to soil. Progeny were then rescreened by growing seedlings under repressive conditions, clearing the roots at 13 d and counting lateral root initiation sites under the microscope (see “Materials and Methods”). Several lateral root initiation (lin) mutants were isolated that reproducibly show increased lateral root initiation under the repressive conditions. We have focused on one of these mutants, lin1, because of its strong phenotype (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Phenotype of lin1. A, Wild-type Col seedlings (left) and lin1 seedlings (right) were grown for 10 d on repressive 4.5/0.02 media (see text). The roots were then cut with a razor blade approximately 0.5 cm from the root tip. Seven days after tip excision, the lin1 roots are highly branched, whereas few if any lateral roots can be observed in the wild-type seedlings. B, Close-up of the aerial parts of wild-type and lin1 seedlings at 17 d. The wild-type seedling leaves are red or brown, whereas the lin1 leaves are green. The aerial tissues of wild type and mutant are severely stunted by the nitrogen starvation conditions. A wild-type seedling grown for 17 d on standard media is shown for comparison. Bar = 2 mm.

Genetic Characterization of lin1

lin1 mutants were backcrossed to Col wild-type plants two times. The segregating F2 population from the second backcross was scored to determine the inheritance pattern of the lin1 mutation. The result (41 lin1 seedlings of 177 = 23%) was consistent with a monogenic recessive trait.

The lin1 mutant was crossed to ecotype Wassilewskija wild type for mapping. The lin1 gene was mapped using cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence and simple-sequence length polymorphism markers and standard protocols to analyze DNA from F2 plants (see “Materials and Methods”). lin1 shows linkage to AtEAT1 (three recombinants of 98 chromosomes) and PAI1 (two recombinants of 112 chromosomes). This indicates that the lin1 gene is located near the top of chromosome I.

The lin1 Phenotype Is Specific to Repressive Growth Conditions

The phenotype of lin1 could indicate a lack of response to the repressive 4.5/0.02 growth conditions, or it could be a result of increased lateral root initiation under any conditions. To distinguish between these possibilities, wild-type and lin1 plants were grown on media with various concentrations of Suc and nitrogen (Table II). The lin1 and wild-type seedlings initiated similar numbers of lateral roots when grown on commercial Murashige and Skoog media (Gibco-BRL) with 4.5% (w/v) Suc (4.5/60) or on 0.5/0.02 media, indicating that lin1 is not a constitutive overproducer of lateral roots (Table II). Therefore, the increased lateral root initiation phenotype of lin1 is observed only under repressive nutrient conditions. This suggests that the mutation in lin1 specifically affects the regulation of lateral root initiation in response to nutritional signals.

Table II.

Lateral root initiation in wild type and lin1

| Media | Plant | Lateral Rootsa | Lengthb | Lateral Roots |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cm | ||||

| 4.5 /0.02 | Col | 4.6 ± 1.6 | 3.71 ± 0.44 | 1.24 |

| 4.5 /0.02 | lin1 | 27.2 ± 5.0 | 5.65 ± 0.46 | 4.80 |

| 0.5 /0.02 | Col | 23.8 ± 3.8 | 4.26 ± 0.63 | 5.59 |

| 0.5 /0.02 | lin1 | 34.8 ± 10.5 | 5.1 ± 0.73 | 6.82 |

| 4.5 /60 | Col | 22.5 ± 2.6 | 5.7 ± 0.40 | 3.95 |

| 4.5 /60 | lin1 | 21.9 ± 2.7 | 5.7 ± 0.40 | 3.84 |

All lateral roots and microscopic root primordia were counted on 13-d-old Col seedlings. Means ± sd are given for 10 roots.

Root length was measured from hypocotyl/root junction. Means ± sd are given for 12 to 20 roots.

The lin1 Mutant Has Increased Growth Rates and Decreased Anthocyanin Accumulation when Grown under Repressive Conditions

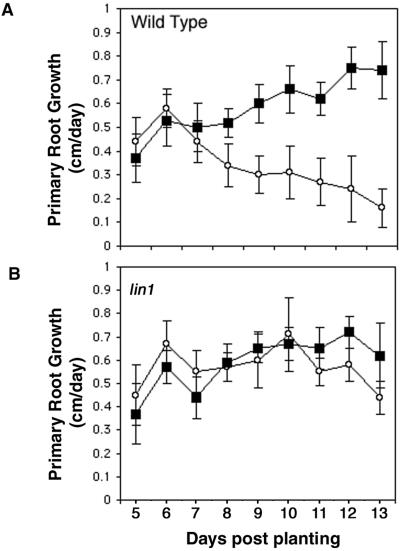

When wild-type seedlings were grown on 4.5/0.02 media the rate of primary root elongation started to decline at d 6 and rapidly decreased thereafter (Fig. 2A, white circles). In contrast, seedlings grew at a steady or increasing rate when nitrogen was plentiful (black squares). The difference could simply be a result of nitrogen availability. An alternative possibility is that inhibition of primary root growth is an active response to specific nutrient conditions. Consistent with this model, lin1 growth rates were similar irrespective of the amount of nitrogen available in the media (Fig. 2B). The increased growth rate of the lin1 mutant resulted in seedlings with much longer root length on 4.5/0.02 media than wild type (Table II). We scored the growth rate and lateral root initiation levels of plants in the F2 generation of a lin1 × Col backcross to ensure that the lin1 mutation was responsible for the growth phenotype. The increased root length cosegregated with the lin1 phenotype (increased lateral root initiation) 76 out of 76 times.

Figure 2.

Growth rate of wild-type (A) and lin1 (B) seedlings on 4.5/60 (squares) and 4.5/0.02 (white circles) media. The root tips of seedlings were marked each day beginning 4 d post-planting. After 13 d, the distances between each mark were measured for each plant. The average root growth for each time period is shown in the graph, with time point 5 indicating the average growth from d 4 to 5 and so on. Growth rates of wild-type seedlings were dramatically inhibited by the 4.5/0.02 media compared with the standard 4.5/60 media. In contrast, lin1 showed similar growth rates on both media. Rates are averages from 12 to 20 plants. Error bars = ±sd.

An additional phenotype of lin1 is that the seedlings are clearly green on 4.5/0.02 media, whereas wild-type seedlings appear dark red (Fig. 1B). Increased anthocyanin accumulation under high carbon to nitrogen ratios has been previously observed in wild-type seedlings (Boxall et al., 1996). Quantitation confirmed that lin1 seedlings accumulated on average only 25% of the anthocyanin levels of wild type (not shown; see “Materials and Methods”). These results suggest that anthocyanin accumulation, primary root growth, and lateral root initiation are active responses to nutritional cues and that the lin1 gene is involved in regulating all these responses.

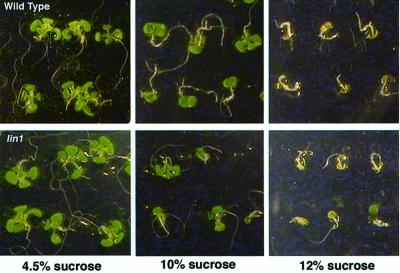

The lin1 Mutant Is Suc Responsive

One possibility consistent with all the above data is that the lin1 gene is essential for Suc uptake or recognition. In this scenario, the lin1 seedlings grown on media with a high Suc to nitrogen ratio would “see” a low Suc to nitrogen ratio. To test this possibility, we compared the effects of high concentrations of Suc on the growth of lin1 and wild-type seedlings. Suc severely inhibits seedling development. This response is genetically separable from osmotic growth inhibition (Laby et al., 2000) and has been used to identify mutants in sugar response pathways. In our media, 10% (w/v) Suc (0.34 m) resulted in small seedlings with green cotyledons and reduced root growth, whereas 12% (w/v) Suc (0.35 m) resulted in seedlings with pale or white cotyledons and minimal root growth (Fig. 3). Thus, these two concentrations were used to compare the Suc sensitivity of lin1 and wild-type plants. Under both conditions, lin1 seedlings were indistinguishable from wild type (Fig. 3). Therefore, although the lin1 gene may be involved in sugar response pathways that are specific to root system development, it is unlikely the lin1 mutants are unable to take up or recognize Suc in the media.

Figure 3.

Development of wild-type and lin1 mutant seedlings on high Suc. Top, Wild-type seedlings; bottom, lin1 seedlings. Two plates of 50 seeds each were sown on standard Murashige and Skoog media (containing 4.5%, 10%, or 12% [w/v] Suc as indicated and 60 mm nitrogen [20 mm KNO3 and 20 mm NH4NO3]) and grown for 12 d. All seeds germinated and seedlings produced healthy roots and green cotyledons and primary leaves when grown on 4.5% (w/v) Suc. On 10% (w/v) Suc, the plants were much smaller, with green cotyledons but only small primary leaves and reduced roots. On 12% (w/v) Suc, no primary leaves formed, the cotyledons were white, and there was very little growth of the primary root. These phenotypes were similar between wild-type and lin1 mutant seedlings. Shown are representative seedlings.

Lateral Root Initiation May Be Regulated by the Localization of Active Auxin

Compelling evidence indicates that auxin from the aerial tissues of the plant is essential for lateral root initiation (Reed et al., 1998). Therefore, one possible mechanism for repression of lateral root initiation on 4.5/0.02 media is that auxin is not reaching the root. If this is the case, exogenously applied auxin should restore lateral root formation. To test this, 5-d-old wild-type seedlings were transferred from repressive media to the same media containing 100 nm α-naphthalene acetic acid (NAA). Seven days later, both the transferred and newly formed regions of the primary roots were examined for lateral root initiation (Table III). NAA was effective at increasing the initiation of lateral roots in plants under standard (4.5/60) or repressive (4.5/0.02) growth conditions. The fact that NAA can induce lateral root initiation in the repressed roots is consistent with the idea that auxin is limiting in these tissues.

Table III.

Effect of NAA on lateral root (LR) initiation in wild-type primary roots

| Mediaa | NAAb | Transferred Region

|

New Growth

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR no.c | Lengthd | LR | LR no.c | Lengthd | LR | ||

| cm | cm | ||||||

| 4.5/60 | – | 2.6 ± 1.50 | 1.1 ± 0.20 | 2.4 | 15.2 ± 5.20 | 4.7 ± 0.37 | 3.2 |

| 4.5/60 | + | 11.1 ± 1.80 | 1.2 ± 0.15 | 8.95 | 65.1 ± 6.20 | 3.5 ± 0.29 | 18.6 |

| Fold increase over control | – | – | 3.8 | – | 5.8 | ||

| 4.5/0.02 | – | 4.7 ± 0.78 | 1.48 ± 0.25 | 3.1 | 7.9 ± 3.90 | 4.1 ± 0.41 | 1.9 |

| 4.5/0.02 | + | 7.5 ± 2.10 | 1.40 ± 0.15 | 5.36 | 22.5 ± 6.00 | 2.7 ± 0.22 | 8.3 |

| Fold increase over control | – | – | 1.7 | – | – | 4.4 | |

Seedlings were grown for 5 d on the indicated media. They were then transferred to the same media with or without NAA. Seven days later, the region of the root that was transferred and the region of new growth were separately cleared and analyzed.

NAA, prepared in 0.1 n NaOH, was added to a final concentration of 100 nm. In control plates, an equivalent volume of 0.1 n NaOH was added.

All lateral roots and microscopic root primordia were counted. Lateral root nos. after NAA treatment were sometimes difficult to assess accurately because many of the primordia become confluent. Means ± sd are given for 10 roots.

At the time of transfer, the root tip position was marked on the plate. The length of the transferred region was measured from hypocotyl/root junction to the mark. The new growth was measured from the mark to the root tip. Means ± sd are given for 12 to 20 roots.

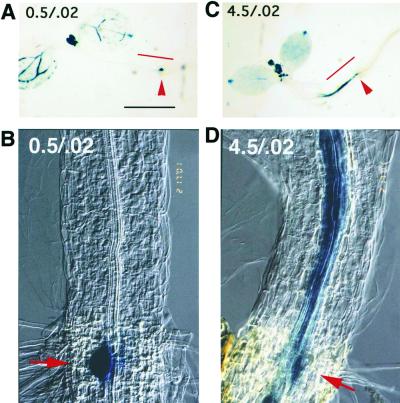

It is interesting that under the repressive growth conditions, we often saw extra layers of stele and adventitious root formation in the hypocotyl (not shown). This phenotype is reminiscent of the appearance of seedlings grown on exogenous auxin, and suggested that auxin might be accumulating in the hypocotyl. To test this possibility, we grew transgenic DR5 plants under repressive or permissive conditions. DR5 transgenic plants contain a multimerized auxin response element fused to the β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene (Ulmasov et al., 1997). Therefore, GUS expression indicates where auxin is present and active in inducing transcription. When 4- to 6-d-old plants were examined, those growing under repressive conditions showed strong GUS expression in the hypocotyl, specifically in the region near the hypocotyl/root junction (Fig. 4, C and D). The strong hypocotyl staining was never observed in plants grown on 0.5/0.02 (Fig. 4, A and B) or 4.5/60 media (not shown). These results suggest that auxin accumulates in the hypocotyl under our repressive nutritional conditions. If this is the case, the lack of lateral root initiation in the primary root might be due to the lack of auxin translocation from the shoot system to the root.

Figure 4.

GUS expression in DR5 transgenic plants under different Suc to nitrogen ratios. A and B, Photos of representative 6-d-old wild-type seedlings grown on 0.5/0.02 media; C and D, Similar seedling grown on 4.5/0.02 media. The regions indicated by the red lines in A and C are shown in the micrographs in B and D, respectively. The arrows indicate the hypocoyl/root junction. A and B, The hypocotyls of seedlings grown on 0.5/0.02 show no staining. The blue spot at the junction in A and B is a lateral root primordium. C and D, The hypocotyls of seedlings grown on 4.5/0.02 media are intensely stained. The staining is in the lower half of the hypocotyl, starting at the hypocotyl root junction and extending up the hypocotyl. The extent of the stained region differs from seedling to seedling. Also, note the increased thickness of the hypocotyl stele in D. Bar in B and D = 1 mm.

lin1 Mutants Are Not Defective in Auxin Response or Sensitivity

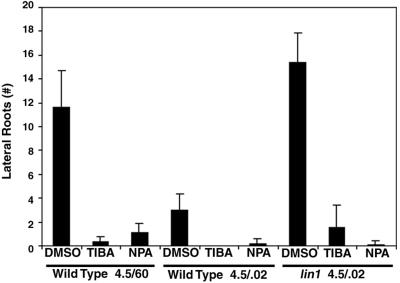

If lateral root initiation is inhibited on 4.5/0.02 media because of reduced auxin translocation, lin1 mutants must somehow be able to overcome this obstacle. The mutation may prevent the reduction of auxin flow to the root. Alternatively, lin1 plants may have increased sensitivity to the small amounts of auxin that do reach the root. A final possibility is that lin1 mutants may initiate lateral roots independent of translocated auxin. Auxin independence was addressed by asking whether the auxin transport inhibitors N-1-naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA) and 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (TIBA) would eliminate the lin1 phenotype. If lateral root initiation in lin1 is independent of auxin from the aerial tissues, transport inhibitors should have no effect. lin1 plants were grown under repressive or standard conditions for 5 d and then transferred to the same media containing TIBA, NPA, or solvent alone (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]). After 7 more d, the region of the primary root that grew after transfer was examined for lateral root initiation. Both TIBA and NPA severely reduced lateral root initiation in wild-type plants grown under standard conditions, as has been previously demonstrated (Reed et al., 1998; Fig. 5). Under repressive conditions, both wild-type and lin1 roots showed very little if any lateral root initiation after transfer to polar transport inhibitors. Hence, the lin1 phenotype is abrogated by auxin transport inhibitors, indicating that lateral root initiation is not auxin independent in this mutant.

Figure 5.

Effects of auxin transport inhibitors on lateral root initiation in wild type and lin1. Five-day-old seedlings were transferred to media containing DMSO alone or the auxin transport inhibitors TIBA (20 μm) and NPA (10 μm) dissolved in DMSO. At d 12, the lateral roots and lateral root primordia produced in the new growth were counted on 10 seedlings. TIBA and NPA were highly effective in reducing lateral root initiation in wild-type seedlings grown on standard media or on 4.5/0.02 media when compared with DMSO controls. Initiation was also dramatically reduced in the new growth of lin1 roots. Error bars = ±sd.

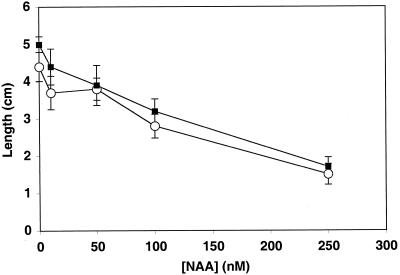

As mentioned above, an increased sensitivity to auxin might also explain the lin1 phenotype. Auxin sensitivity was assessed by growing lin1 and wild-type seedlings under standard conditions (4.5/60) for 5 d and then transferring them to various concentrations of NAA. Auxin sensitivity is often measured based on the reduction in primary root growth (Evans et al., 1994). The NAA-induced decrease in primary root growth was indistinguishable between wild-type and lin1 seedlings (Fig. 6), suggesting that the lin1 gene does not affect auxin sensitivity. In the alf4 mutant, primary root growth is inhibited by auxin but lateral root initiation is not induced, indicating that these two responses to auxin are separable (Celenza et al., 1995). Therefore, we also assessed the induction of lateral root initiation by NAA. Again, lin1 and wild-type responses to auxin were indistinguishable (Table IV). Hence, the lin1 mutant is not affected in overall auxin sensitivity and still requires auxin for lateral root initiation. Taken together, these data suggests that the lin1 gene may be essential in coordinating lateral root initiation with environmental cues by regulating auxin localization.

Figure 6.

Effect of NAA on primary root elongation in wild-type and lin1 seedlings. Seedlings were grown for 5 d on standard Murashige and Skoog media (4.5/60). They were then transferred to the same media containing various concentrations of NAA as indicated, and the position of the root tip was marked. Seven days later, the new growth was measured from the mark. Lengths are averages of 15 to 25 plants. Error bars = ±sd.

Table IV.

Effect of NAA on lateral root initiation in wild-type and lin1 roots

| NAAa | Col

|

lin1

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR no.b | Lengthc | LR | LR no.b | Lengthc | LR | |

| nm | cm | cm | ||||

| 0 | 13.4 ± 3.1 | 4.4 ± 0.39 | 3.0 | 18.7 ± 3.5 | 5.0 ± 0.21 | 3.7 |

| 10 | 14.5 ± 3.2 | 3.7 ± 0.45 | 3.9 | 20.1 ± 2.8 | 4.4 ± 0.48 | 4.6 |

| 50 | 36.7 ± 4.7 | 3.8 ± 0.30 | 9.7 | 38.7 ± 11.8 | 3.9 ± 0.54 | 9.9 |

| 100 | 49.6 ± 6.2 | 2.8 ± 0.32 | 17.7 | 60.4 ± 8.7 | 3.2 ± 0.33 | 18.9 |

Seedlings were grown for 5 d on standard Murashige and Skoog media (4.5/60). They were then transferred to the same media containing various concentrations of NAA as indicated, and the position of the root tip was marked. Seven days later, the region of new growth was excised, cleared, and analyzed.

All lateral roots and microscopic root primordia were counted. Lateral root nos. after NAA treatment were sometimes difficult to assess accurately because many of the primordia become confluent. Means ± sd are given for 10 roots.

Length of the newly grown region of the root was measured from the mark to the root tip. Means ± sd are given for 12 to 20 roots.

DISCUSSION

Developmental Plasticity in Plants

Because plants are nonmotile, they are completely dependent on the nutrients that are available in their immediate vicinity. Nutrient availability and distribution is in constant flux in the environment. For optimal growth, a plant must be able to sense these changes and respond appropriately. Plants have evolved ingenious strategies to meet this challenge (Trewavas, 1986a). Their responses take many forms, including changes in metabolic activity, gene expression, and morphology (Trewavas, 1986; Grime et al., 1986; Callahan et al., 1997). For example, plants alter the size of leaves and hypocotyl length in response to sunlight (Callahan et al., 1997) and the rate of root growth in response to nitrates and phosphates (Drew and Saker, 1978; Zhang and Forde, 2000; Williamson et al., 2001). These responses also exert secondary effects on overall plant morphology. For example, the masses of the root and shoot system are maintained at a relatively constant ratio so that one does not exceed the needs or capacity of the other. Hence, the developmental plasticity of plants requires a complex network of sensors and both local and long-range signaling pathways. The formation of lateral roots in the root system provides a good model for studying how plant morphology is regulated and coordinated with environmental conditions.

Lateral Root Initiation Is Regulated by Nutritional Conditions

We have shown that lateral root initiation is drastically repressed by high Suc to nitrogen ratios under lab conditions. This response is not due to nitrogen starvation alone because lowering the Suc concentration restored lateral root initiation even under low nitrogen conditions. The idea that sugars and nitrogen salts can affect plant morphology is not unprecedented. Sugars and nitrate ions have been shown to act as signaling molecules (Gibson, 2000; Zhang and Forde, 2000; Coruzzi and Bush, 2001), inducing gene transcription and morphological changes. Furthermore, both photosynthetic activity and nitrogen availability have been implicated in the control of lateral root initiation (Drew and Saker, 1973; Reed et al., 1998). High carbon-to-nitrogen ratios have also been reported to induce a specific set of responses in plants, including induction of metabolic genes (Coruzzi and Bush, 2001) and accumulation of anthocyanins (Boxall et al., 1996). Because of the non-physiological factors involved in growing seedlings on sterile media (i.e. supplying the carbon source through the roots; accumulation of O2 in sealed dishes), it is impossible to discern the natural conditions that are simulated in this assay. Nevertheless, we can conclude that plants are able to control lateral root initiation in response to external nutritional conditions either by sensing nutrients directly or monitoring their internal metabolic status. Therefore, lateral root initiation is the target of a signal transduction pathway that interprets and integrates information about nutrient availability. As such, it is amenable to molecular dissection.

The Nutrient-Mediated Repression of Lateral Root Initiation May Involve the Regulation of Auxin Transport

Our experiments showed that repressive growth conditions can be overcome by the addition of exogenous NAA (Table III). Therefore, nutritional cues are not blocking the root's ability to respond to auxin. Instead, indirect visualization of auxin using the DR5 reporter line suggests that under inhibitory conditions auxin transport is blocked at the hypocotyl root junction, causing auxin to accumulate in the hypocotyl. This would explain the absence of lateral root initiation under these conditions. These data raise the exciting possibility that auxin localization might be regulated in response to nutritional signals. Such ideas have been raised before to explain developmental plasticity and the complex array of responses mediated by auxin (Trewavas, 1986b; Berlath and Sachs, 2001).

DR5 data must be interpreted with caution. GUS expression in DR5 lines indicates only where cells are responding strongly to auxin, not where the auxin is actually located. Therefore, there is no proof that auxin is actually accumulating in the hypocotyl, or more importantly, that it is not reaching the root. It is possible that some other factor required for auxin response is present at unusually high levels in the hypocotyl and absent in the root. Alternatively, some factor other than auxin may travel from the shoot to the root to stimulate cell division. Auxin production is often associated with rapidly dividing tissues. Therefore, in this scenario auxin-induced gene expression in the hypocotyl stele would be a consequence rather than a cause of rapidly dividing cells being present. Direct auxin measurements over a time course will be essential to distinguish between these scenarios. It will also be interesting to assess auxin localization in the lin1 mutant. These experiments are currently in progress.

The lin1 Gene Identifies a Novel Signaling Pathway That Coordinates Nutritional Cues and Lateral Root Initiation

It is striking that among all the morphological mutants isolated in Arabidopsis, very few have been found that have defects in lateral root initiation. The mutants that have been reported fall into two categories: (a) mutants defective in overall auxin response or regulation of auxin levels, such as axr1 through axr6 and sur1 and sur2 (Hobbie, 1998); and (b) mutants specifically affected in lateral root initiation. The only members of the latter category are alf4 and slr, which initiate very few lateral roots even in the presence of exogenous auxin (Celenza et al., 1995; Fukaki et al., 2001). The lin1 mutant falls into a new, third category. It is able to initiate lateral roots and respond to auxin but is not repressed by conditions that drastically reduce lateral root initiation in wild-type plants. Therefore, the lin1 mutant has an intact lateral root formation program but is defective in the signal transduction pathway that stimulates this program. The fact that the lin1 mutant phenotype is only observed under a specific set of growth conditions highlights a reason why lateral root initiation mutants have proven to be so rare. There may be only a few master genes responsible for root system branching per se, but many involved in the signaling pathways that constantly inhibit or stimulate this process in accordance with the changing environment. Under normal growth conditions, mutations in these pathways would not cause drastic increases or reductions in overall lateral root initiation, but would eliminate the plant's ability to fine tune root system morphology in response to cues. These kinds of phenotypes would only be detectable under carefully defined growth conditions such as those described here.

A Model for the Regulation of Lateral Root Initiation

Based on the currently accepted model for lateral root initiation, we can attempt to place the LIN1 gene in a pathway with other known regulatory genes. Auxin from the aerial tissues travels to the root and induces cell division in certain pericycle cells. Levels of auxin are regulated by such genes as ALF1/SUR1 and SUR2 (Delarue et al., 1998), and auxin transport requires specific carrier proteins including members of the PIN1 family (Palme and Galweiler, 1999). ALF4 is required for pericycle cells to either perceive or respond to auxin in the root (Celenza et al., 1995). Because lateral root initiation varies with environmental conditions, one or more of these steps must be subject to regulation by a signal transduction pathway(s) that coordinates nutritional cues and lateral root initiation. Our data show that the LIN1 gene is a key player in one such signal transduction pathway because a mutation in it results in high levels of lateral root initiation in plants grown under a repressive nutritional regime.

LIN1 may act at the earliest stages in this pathway. For example, the LIN1 gene may be involved in sensing levels of Suc or its metabolites, or in interpreting a Suc to nitrogen ratio. This model is consistent with the fact that the lin1 mutants are defective in multiple responses to high Suc to nitrogen ratios (inhibition of lateral root initiation, repression of primary root growth, and anthocyanin accumulation). However, LIN1 is unlikely to be involved in Suc uptake because mutant and wild-type plants showed equivalent responses to Suc in seedling growth assays (Fig. 3). The LIN1 gene could also act by modulating the movement of auxin in response to environmental conditions (see above). This could also account for the multiple responses that are affected in the lin1 mutant. Finally, the LIN1 gene may limit the ability of auxin to stimulate pericycle cells. However, the lin1 mutant does not have increased numbers of lateral roots under normal growth conditions, nor does it bypass the need for auxin in lateral root initiation. Therefore, the activity of LIN1, at whatever point it acts, must be somehow coordinated with a perception of growth conditions.

In summary, the lin1 mutant provides the first evidence for molecular regulation of lateral root initiation in response to nutritional signals. The pathway mediated by LIN1 is crucial for coordinating the morphology of the root system with environmental cues. Cloning of the LIN1 gene clearly will provide greater insights into the mechanisms that regulate root system development and the role of LIN1 in this process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth Conditions

All seeds were surface sterilized in commercial bleach solution containing three drops of Tween 20 (10 mL) for 3 min followed by three washes in sterile water. Sterilized seeds were refrigerated for 2 d in water and then sown on Murashige and Skoog media with modifications as described in the text. 4.5/60 media was prepared using Gibco-BRL Murashige and Skoog basal salts (no. 11117-066) supplemented with 0.5 g L−1 MES [2-(N-morhpholino) ethanesulfonic acid] and 45 g L−1 Suc. pH was adjusted to 5.7 using 1 n KOH and 0.7% (w/v) BRL Ultrapure Agar (no. B-11849, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh) was added before autoclaving. 4.5/0.02 and 0.5/0.02 media were made using nitrogen-free Murashige and Skoog salts specially ordered from Gibco-BRL supplemented with 10 μL L−1 1 m NH4NO3. Plates were oriented vertically to allow roots to grow on the surface of the media in a growth chamber set at 22°C for 16 h in light and 8 h in dark.

Microscopy

All tissues were cleared by incubating sequentially for 5 to 15 min each in: (a) 20% (v/v) methanol acidified with 4% (v/v) concentrated hydrochloric acid, 55°C; and (b) 7% (w/v) NaOH in 60% (w/v) ethanol. Tissues were then rehydrated by 10-min incubations in 40%, 20%, and 10% (v/v) ethanol and then infiltrated for 10 min in 50% (v/v) glycerol/5% (v/v) ethanol. Cleared tissues were then mounted in 50% (v/v) glycerol and visualized using DIC optics on a DMR microscope (Leica Microsystems, Deerfield, IL). Pericycle cells that have undergone anticlinal divisions, defined as a stage I primordium (Malamy and Benfey, 1997a), can be easily visualized using this protocol.

Isolation of Mutants

One thousand M2 seeds (ecotype Col) that had been mutagenized with ethyl methanesulfonate were planted on 4.5/0.02 media. At 10 d, the primary root tips were excised approximately 5 mm from the end using a sterile scalpel and the seedlings were allowed to continue to grow for an additional 7 to 10 d. Plants that produced four or more lateral roots under these conditions were transferred to 4.5/60 media to recover and eventually transplanted to soil. Progeny were then retested under similar conditions. Plants that reproducibly showed the lin phenotype were confirmed by scoring lateral root initiation microscopically, without tip excision.

Genetic Analysis and Mapping

The lin1 mutant was crossed to wild-type Col and a single F2 plant, lin1C, was selected. This plant was again crossed to Col. The F2 progeny of this second backcross were used to assess the inheritance of the lin1 phenotype and the cosegregation of this phenotype with increased growth rate. Cosegregation was scored by growing plants on 4.5/0.02 media for 15 d. Growth rates were determined by marking the position of the root tip on the plate every 24 h for 6 d. Distances between the marks were then measured. At the end of the experiment, plants with four or more visible lateral roots were scored as positive for the lin phenotype. The growth rate of all of the positive lin1 plants was higher than that of the remaining plants. lin1C was crossed to ectotype Wassilewskija and the F2 progeny of this cross were used for mapping of the lin1 gene. Plants that scored positive for the lin1 phenotype were verified by examining a selfed F3 population for each individual. DNA was isolated from these plants using the method of Elliot M. Meyerowitz (http://www.its.caltech.edu/∼plantlab/protocols/quickdna.html). Standard simple-sequence length polymorphism and cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence PCR conditions were used. Map positions of the markers were taken from the Lister and Dean RI map (http://www.Arabidopsis.org).

Anthocyanin Determination

Relative anthocyanin levels were assayed as described in Laby et al. (2000). In brief, Col and lin1 seedlings were grown for 15 d on 4.5/0.02 media. Roots were excised and 10 to 20 mg of the remaining tissue was weighed in a 1.5-mL centrifuge tube. The tissue was than extracted overnight at 4°C with 500 μL methanol:HCl (99:1, v/v). The optical density (OD)530 and OD657 for each sample was measured and the relative anthocyanin levels determined using the equation: OD530 − (0.025 × OD657) × extraction voume (mL) × 1/weight of tissue (mg) = relative units of anthocyanin/mg fresh weight of tissue. The experiment was performed in triplicate. Values for wild-type plants ranged from 0.0013 to 0.014 (average 0.0073 ± 0.005). Values for lin1 plants ranged from 0.025 to 0.033 (average 0.029 ± 0.004).

Analysis of GUS Activity

GUS activity was assayed by immersing seedlings for 2 to 3 d in a staining solution at 37°C. The staining solution was composed of 1 mL 5× buffer, 1 mL methanol, 5 mg X-Gluc (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-beta-d-GlcUA, cyclohexylammonium salt; Biosynth Ag no. B-7300), 3 mL Water. The 5× buffer was composed of: 9 mL 0.5 m Phosphate buffer, pH 7.0; 1 mL 0.5 m EDTA; 106 mg K4FeCn6; and 82 mg K3FeCn6. Stained tissues were cleared as described above.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Dr. Philip Benfey for his support and helpful insights throughout the course of this work. We also thank Dr. Jean Greenberg, Dr. Daphne Preuss, and members of the Greenberg, Preuss, and Malamy labs for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant no. GM43778 to Dr. Philip Benfey, New York University), and by the Louis Block Foundation (grant to J.E.M.).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.010406.

LITERATURE CITED

- Atkinson D, Hooker J. Using roots in sustainable agriculture. Chem Ind. 1993;4:14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Beeckman T, Burssens S, Inze D. The peri-cell-cycle in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2001;52:403–411. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.suppl_1.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlath T, Sachs T. Plant morphogenesis: long distance coordination and local patterning. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2001;4:57–62. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerjan W, Cervera M, Delarue M, Beeckman T, Dewitte W, Bellini C, Caboche M, Van Onckelen H, Van Montagu M, Inzé D. superroot, a recessive mutation in Arabidopsis, confers auxin overproduction. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1405–1419. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.9.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxall S, Martin T, Graham IA. A new class of Arabidopsis mutants that are carbohydrate insensitive. Seventh International Conference on Arabidopsis Research (abstract no. S96). UK: Norwich; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan HS, Pigliucci M, Schlichting CD. Developmental phenotypic plasticity: where ecology and evolution meet molecular biology. BioEssays. 1997;9:519–525. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celenza JL, Jr, Grisafi PL, Fink GR. A pathway for lateral root formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2131–2142. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.17.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charleton WA. Lateral root initiation. In: Waisel Y, Eshel A, Kafkafi U, editors. Plant Roots: The Hidden Half. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1991. pp. 103–128. [Google Scholar]

- Coruzzi G, Bush DR. Nitrogen and carbon nutrient and metabolite signaling in plants. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:61–64. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delarue M, Prinsen E, Van Onckelen H, Caboche M, Bellini C. Sur2 mutations of Arabidopsis thaliana define a new locus involved in the control of auxin homeostasis. Plant J. 1998;12:603–611. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDonato R, Arbuckle E, Sheets J, Celenza J. Positional cloning and characterization of ALF4, a gene required for lateral root formation. 12th International Conference on Arabidopsis Research (abstract no. 444). WI: Madison; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Drew MC. Comparison of the effects of a localized supply of phosphate, nitrate, ammonium and potassium on the growth of the seminal root system, and the shoot, in barley. New Phytol. 1975;75:479–490. [Google Scholar]

- Drew MC, Saker LR. Nutrient supply and the growth of the seminal root system in barley. J Exp Bot. 1978;29:435–451. [Google Scholar]

- Drew MC, Saker LR, Ashley TW. Nutrient supply and the growth of the seminal root system in barley. J Exp Bot. 1973;24:1189–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Dubrovsky JG, Doerner PW, Colon-Carmona A, Rost TL. Pericycle cell proliferation and lateral root initiation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:1648–1657. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.4.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans ML, Ishikawa H, Estelle MA. Responses of Arabidopsis roots to auxin studied with high temporal resolution: comparison of wild type and auxin response mutants. Planta. 1994;194:215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Fukaki H, Tameda S, Masuda H, Matsui R, Tasaka M. Lateral root formation is blocked by a gain-of-function mutation in the Solitary Root/IAA14. 12th International Conference on Arabidopsis Research (abstract no. 448). WI: Madison; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson SI. Plant sugar-response pathways: part of a complex regulatory web. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:1532–1539. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.4.1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP, Crick JC, Rincon JE. The ecological significance of plasticity. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1986;40:4–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie LJ. Auxin: molecular genetic approaches in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1998;36:91–102. [Google Scholar]

- King JJ, Stimart DP, Fisher RH, Bleecker AB. A mutation altering auxin homeostasis and plant morphology in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1995;7:2023–2037. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.12.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laby RJ, Kincaid MS, Kim D, Gibson SI. The Arabidopsis sugar-insensitive mutants sis4 and sis5 are defective in abscisic acid synthesis and response. Plant J. 2000;23:587–596. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyser O, Fitter A. Roots are branching out in patches. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3:203–204. [Google Scholar]

- Malamy JE, Benfey PN. Organization and cell differentiation in lateral roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 1997a;124:33–44. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamy JE, Benfey PN. Down and out in Arabidopsis: the formation of lateral roots. Trends Plant Sci. 1997b;2:390–396. [Google Scholar]

- Palme K, Galweiler L. PIN-pointing the molecular basis of auxin transport. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1999;2:375–381. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(99)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed RC, Brady SR, Muday GK. Inhibition of auxin movement from the shoot into the root inhibits lateral root development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:1369–1378. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.4.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrey J. Endogenous and exogenous influences on the regulation of lateral root formation. In: Jackson MB, editor. New Root Formation in Plants and Cuttings. Hingham, MA: Martinus Nijhoff; 1986. pp. 31–66. [Google Scholar]

- Trewavas A. Resource allocation under poor growth conditions: a major role for growth substances in developmental plasticity. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1986;40:31–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T, Murfett J, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ. Aux/IAA protein repress expression of reporter genes containing natural and highly active synthetic auxin response elements. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1963–1971. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.11.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson L, Ribrioux S, Fitter A, Leyser O. Phosphate availability regulates root system architecture in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:875–882. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.2.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Forde BG. Regulation of Arabidopsis root development by nitrate availability. J Exp Bot. 2000;51:51–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]