Abstract

A general strategy for creating nanocavities with tunable sizes based on the folding of unnatural oligomers is presented. The backbones of these oligomers are rigidified by localized, three-center intramolecular hydrogen bonds, which lead to well-defined hollow helical conformations. Changing the curvature of the oligomer backbone leads to the adjustment of the interior cavity size. Helices with interior cavities of 10 Å to >30 Å across, the largest thus far formed by the folding of unnatural foldamers, are generated. Cavities of these sizes are usually seen at the tertiary and quaternary structural levels of proteins. The ability to tune molecular dimensions without altering the underlying topology is seen in few natural and unnatural foldamer systems.

Based on the folding of biopolymers, Nature has developed astonishingly efficient and sophisticated strategies for generating various nanostructures. Of particular interests is the availability of a wide variety of nanosized cavities and holes that are responsible for numerous biological processes and functions. In recent years there has been intense interest in developing folding oligomers and polymers (foldamers) with unnatural backbones that adopt well-defined structures (1–3), which may eventually lead to protein-like molecular objects with sizes in the nanometer range. Many foldamer systems have been described (4–16). Despite the progress made so far, the foldamer field is still in its infancy. One daunting challenge involves the design of foldamers with cavities and holes of tunable sizes in the nanometer range, the realization of which will have far-reaching significance for not only fundamental understanding but also important applications. While cavities and holes are mostly seen at the tertiary and quaternary structural levels of biopolymers, almost all foldamers reported so far fold into secondary structures. In this article we describe a general strategy for designing folded structures that combine the features of both secondary and tertiary (or quaternary) structures. Nanosized cavities are generated by enforcing stably folded helical structures. In addition, by adjusting the curvature of the corresponding backbones, the interior diameters of these hollow helices are easily tuned. This tunability is seen in few natural or unnatural folding systems. Thus, helices with hydrophilic interior cavities of ∼10 Å and >30 Å across result, yielding cavities of tunable sizes and properties. Many novel properties may emerge given, the tunable and distinct cavities associated with the corresponding folding molecules, and numerous applications in catalysis, separation, molecular recognition, and transportation can be envisioned. Phenomena associated with nanodimensions that lately have attracted intense interest and have been probed by using the highly hydrophobic carbon nanotubes (17, 18) can also be investigated on the basis of the hydrophilic cavities of these hollow helices.

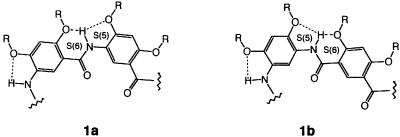

Our design is based on oligoamides represented by the general structures 1a and 1b. The backbone of these oligomers consists of benzene rings linked by localized, intramolecularly hydrogen-bonded amide groups. On each of the benzene rings, the two amide linkages can be placed meta to each other (m-residue), leading to backbones consisting of m-residues (m-backbones, 1a), or with some of the residues, the two amide groups can be placed in a para geometry (p-residue), leading to backbones consisting of m- and p-residues (mp-backbones, 1b).

|

Our previous studies have demonstrated that short oligomers with m-backbones adopt a well-defined crescent conformation (12, 19, 20). Our results indicated that the three-center hydrogen-bonding system, consisting of the S(5) and S(6) type (21) hydrogen-bonded rings, was particularly stable in the solid state and in solution (19, 20). It persisted in chloroform, the highly polar dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and even in water (unpublished data), and this structure was confirmed by NMR, IR, and x-ray crystallographic studies on short oligomers. Extending the crescent backbones may lead to helical conformations.

Materials and Methods

Compounds.

All compounds described herein gave satisfactory NMR and electrospray ionization (ESI) MS results consistent with their structures. The short oligomer intermediates were prepared by iterative coupling steps based on similar procedures described before (12).

Compound 2a.

To a solution of 4,6-bis{2-[2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy}-1,3-benzenedicarboxylic acid (0.049 g, 0.10 mmol) and tetramer amine 4a was added N,N-diisopropylethylamine (1 ml), followed by slow addition of O-(7-azabenzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (0.076 g, 0.20 mmol) in dimethylformamide (DMF; 1 ml) during 10 min at 50°C under nitrogen atmosphere. The mixture was changed into solution, which was stirred overnight. The precipitate from the solution at −20°C was collected and washed with cold DMF and ethyl acetate to give pure 2a as a solid (0.093 g, 37%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.23 (s, 2H), 10.05 (s, 2H), 9.77 (s, 2H), 9.62 (s, 2H), 9.22 (s, 2H), 9.10 (s, 2H), 8.95 (s, 1H), 8.91 (s, 2H), 8.55 (s, 2H), 6.76 (d, 2H, J = 7.0 Hz), 6.72 (d, 2H, J = 7.0 Hz), 6.58 (s, 1H), 6.52 (br, 4H), 6.45 (s, 2H), 4.38(br, 4H), 4.26 (br, 8H), 3.94–4.04 (m, 40H), 3.41–3.73 (m, 48H), 3.30 (s, 6H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 3.27 (s, 6H), 2.30 (s, 6H), 1.24–1.41 (m, 24H), 0.84 (t, 6H, J = 6.8 Hz). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.99, 162.84, 162.58, 162.16, 160.13, 155.27, 154.70, 154.06, 153.51, 153.40, 151.79, 145.77, 130.42, 129.06, 125.52, 125.36, 123.15, 122.52, 121.77, 121.19, 115.73, 115.09, 114.36, 113.89, 110.84, 97.82, 95.32, 72.06, 72.00, 70.86, 70.70, 70.60, 70.54, 70.51, 69.70, 69.45, 69.29, 68.02, 68.72, 59.08, 59.06, 59.03 56.66, 56.42, 56.34, 32.00, 29.76, 29.57, 29.49, 26.14, 22.84, 21.35, 14.29. Exact mass calculated for C130H182N8O42Cl: 2562.20; MS (ESI, negative mode), 2561.68.

Compound 2b.

To a solution of tetramer amine 4b, prepared by reducing (H2/Pd–C) the corresponding nitro tetramer (0.40 g, 0.44 mmol), and triethylamine (3 ml) in CH2Cl2 (15 ml), was added 4,6-dioctyloxybenzene-1,3-dicarboxylic dichloride in 10 ml CH2Cl2, prepared from the corresponding acid by refluxing in thionyl chloride. The solution was stirred overnight at room temperature. The precipitated solid was filtered off and washed with CH2Cl2 to give pure nonamer 2b (0.18 g, 38%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 60°C) δ 9.98 (s, 2H), 9.91 (s, 2H), 9.90 (s, 2H), 9.56 (s, 2H), 9.06 (s, 2H), 9.02 (s, 2H), 8.79 (s, 2H), 8.76 (s, 2H), 8.65 (s, 1H), 6.94 (s, 3H), 6.88 (s, 2H), 6.85 (s, 2H), 6.80 (s, 2H), 4.38 (t, 4H, J = 6.0 Hz), 4.02–4.08 (m, 28H), 3.97 (s, 6H), 3.84 (s, 6H), 3.73 (s, 6H), 2.10–2.25 (m, 8H), 1.85 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 4H), 1.18–1.43 (m, 20H), 1.00–1.08 (m, 48H), 0.78 (t, 6H, J = 6.8 Hz). Analysis. Calculated for C122H162N8O30: C, 65.97; H, 7.37; N, 5.04. Found: C, 65.76; H, 7.41; N, 5.01.

Compound 6.

To a solution of diacid (0.037 g, 0.088 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (10 ml) and several drops of DMF was added oxalyl chloride (0.10 ml, 1.14 mmol) dropwise. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 20 min, then heated under reflux for 10 more min. Evaporation of the solvent gave the crude acid chloride, which was directly used in the next step without further purification. A mixture of the corresponding heptamer amine (0.360 g, 0.183 mmol), 10% Pd–C (0.072 g, 20% weight of the compound) in MeOH/CHCl3 (10 ml/10 ml) was degassed and stirred under H2 [4.0 bar (1 bar = 100 kPa)] at 25°C for 2 hr. The mixture was then filtered and the solvent was removed under vacuum. The residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2, washed with dilute sodium bicarbonate solution, and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. Removal of solvent gave the crude 7-mer amine, which was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (10 ml), to which Et3N (0.019 g, 0.186 mmol) was added, followed by the dropwise addition of the above acid chloride in CH2Cl2 (5 ml). The solution was stirred for 4 hr at room temperature. After the removal of the solvent, the residue was triturated with MeOH to give crude product (0.355 g, 95%), some of which was further subjected to preparative thin-layer chromatography to give the pure product as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, 60% DMSO-d6/CDCl3) δ 10.66 (s, 2H), 10.65 (s, 4H), 10.51 (s, 2H), 10.49 (s, 2H), 10.41 (s, 4H), 10.39 (s, 2H), 10.25 (s, 2H), 9.29 (s, 4H), 9.26 (s, 2H), 8.98 (s, 1H), 8.47 (br, 6H), 8.41 (s, 2H), 7.93 (br, 6H), 7.02 (s, 4H), 6.93 (s, 1H), 6.89 (d, 2H, J = 5.5), 6.84 (d, 2H, J = 5.0), 6.80 (s, 2H), 4.58 (br, 8H), 4.49 (br, 4H), 4.45 (br, 8H), 4.27–4.25 (m, 8H), 4.14 (s, 6H), 4.13 (s, 6H), 4.09 (s, 6H), 4.02–3.97 (m, 34H), 3.89 (s, 6H), 3.72 (br, 8H), 3.65 (br, 8H), 3.62 (br, 8H), 3.55 (br, 8H), 3.51 (br, 8H), 3.44 (br, 24H), 3.25 (s, 12H), 3.22 (s, 12H), 2.31 (s, 6H), 2.05 (m, 4H), 1.95 (m, 8H), 1.60 (m, 4H), 1.54 (m, 4H), 1.47 (m, 4H), 1.42 (m, 8H), 1.36 (m, 4H), 1.34–1.22 (m, 32H), 0.88 (t, 6H, J = 4.5), 0.87–0.83 (m, 12H). Exact mass calculated for C224H316N14O66: 4258.18. MS (ESI, positive mode) 4258.47.

Compound 7.

To a solution of Et3N (0.035 g, 0.34 mmol) and the corresponding decamer amine in CH2Cl2 (5 ml), prepared by reducing (10% Pd–C: 0.05 g; H2: 4.0 bar) the corresponding nitro compound (0.300 g, 0.120 mmol) in MeOH/CHCl3 (10 ml/10 ml) at 30–35°C for 2 hr, was added dropwise a solution of 4,6-diisopropyloxybenzene-1,3-dicarboxy chloride in CH2Cl2 (3 ml), which was prepared from the corresponding acid (0.017 g, 0.060 mmol) by treating with oxalyl chloride (0.05 ml, 0.57 mmol) and several drops of DMF (as catalyst) in CH2Cl2 (10 ml) at room temperature for 1 hr. The solution was stirred for 4 hr at room temperature. After the removal of the solvent, the residue was triturated with MeOH to give the crude product, which was further subject to preparative thin-layer chromatography [86:8:6 (vol/vol) CH2Cl2/MeOH/ethyl acetate, Rf = 0.3–0.4) to yield pure 21-mer 7 as a white-yellow solid (18 mg, 4%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, 53% DMSO-d6/CDCl3) δ 10.73 (s, 2H), 10.641 (s, 4H), 10.55 (s, 2H), 10.52 (s, 2H), 10.47 (s, 4H), 10.44 (s, 2H), 10.42 (s, 2H), 10.38 (s, 2H), 9.25 (s, 6H), 9.18 (s, 2H), 8.95 (s, 1H), 8.46–8.41 (m, 8H), 8.30 (d, 2H, J = 7.0 Hz), 7.90–7.84 (m, 8H), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 6.85 (s, 2H), 6.89 (s, 4H), 6.71 (m, 4H), 5.16 (br, 2H), 4.53 (s, 8H), 4.41 (s, 8H), 4.32 (s, 4H), 4.23 (s, 4H), 4.17 (s, 6H), 4.09–3.93 (m, 74H), 3.68 (s, 8H), 3.59 (s, 16H), 3.51 (m, 8H), 3.46 (s, 8H), 3.39 (d, 16H), 3.30 (m, 8H), 3.212 (s, 6H), 3.208 (s, 6H), 3.174 (s, 6H), 3.169 (s, 6H), 2.28 (s, 6H), 1.93 (m, 8H), 1.55 (s, 12H), 1.45 (m, 4H), 1.39–1.28 (m, 12H), 1.27–1.19 (m, 24H), 0.83 (t, 6H, J = 6.5 Hz), 0.79 (t, 6H, J = 5.5 Hz). Mass calculated for C268H350N20O84: 5192.37. MS (ESI, positive mode) 5194.39.

X-Ray Data.

Compound 5b was crystallized from ethanol by slow evaporation of solvent (ethanol): space group P1, a = 10.891(3) Å, b = 11.717(3) Å, c = 11.842(3) Å, α = 74.867(5)°, β = 82.817(5)°, γ = 83.711(5)°. Compound 4c was crystallized from DMF by slow cooling: space group P21/c, a = 11.007(2) Å, b = 31.401(6) Å, c = 18.997(3) Å, β = 100.05(1)°. Compound 2b was crystallized from DMF by slow cooling: space group C2/c, a = 18.138(2) Å, b = 47.066(4) Å, c = 32.595(3) Å, β = 104.50(1)°. Compounds 8 and 9 were crystallized from CH3OH/CH2Cl2 by slow evaporation of solvent. Compound 8: space group P2(1)/n, a = 16.116(3) Å, b = 9.253(2) Å, c = 35.630(7) Å, α = 90°, β = 92.275(10)°, γ = 90°. Compound 9: space group P1, a = 11.4923(3) Å, b = 11.6685(3) Å, c = 20.4178(6) Å, α = 76.607(1)°, β = 87.084(1)°, γ = 71.170(1)°.

Results and Discussion

Symmetrical nonamers 2a and 2b were designed to simplify their synthesis, which can be carried out based on a convergent route by combining two amino tetramer fragments with a diacid residue. Nonamers 2a (more soluble) and 2b (less soluble) were synthesized by coupling the corresponding isophthalic acids with the amino tetramers 4a and 4b. The resulting symmetry is readily apparent in one-dimensional (1D) 1H NMR—i.e., the spectrum of 2a contains nearly the same number of peaks as that of 3, whose structure is roughly half of 2a (1D and 2D NMR spectra, distance calculation, and other details are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org).

Ab initio calculations (22) indicate that isophthalamide 5a adopts a flat conformation that is rigidified by the two three-center hydrogen bonds. Alternative conformations of 5a resulted from interrupting the hydrogen bonds are mostly much less stable. The ab initio results are confirmed by the crystal structure of 5b, whose backbone shows a flat conformation enforced by the presence of the two three-center hydrogen bonds (Fig. 1a). Thus, the isophthalamide unit rigidified by three-center hydrogen bonds maintains a conformation in which the two amide carbonyl groups point to the same side. The crystal structure of tetramer 4c was also determined and shows a well-defined crescent backbone with the O atoms of the amide and nitro groups pointing inward (Fig. 1b). Combining the isophthalamide unit with two rigid tetramer units may lead to 9-mers 2 with an overall rigidified curved backbone yielding a helical conformation.

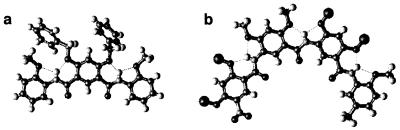

Figure 1.

(a) The crystal structure of 5b in which the three amide-linked benzene rings lie on the same plane. (b) The crystal structure of tetramer 4c. The octyl groups are replaced with dummy atoms (green) for clarity of view.

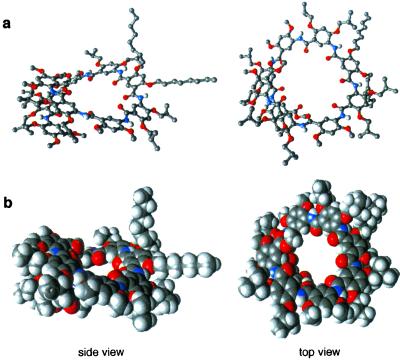

Evidence for a helical conformation was provided by the crystal structure of 9-mer 2b. As shown in Fig. 2, the molecule folds into a helical conformation in the solid state, with the amide O atoms pointing toward the center of a nearly 10-Å cavity. All of the amide protons and the alkoxy O atoms are involved in forming three-center hydrogen bonds. The side chains point radially away from the center of the molecule. There are about seven benzene rings per turn. If all of the backbone atoms had the planar trigonal 120° symmetry typical of sp2 centers, a helix with exactly six benzene rings per turn, thus a smaller interior cavity, would result. However, the crystal structures of 2b, 4c, 5b, and, as shown in Fig. 4, 8 and 9, and two other short oligomers previously reported by us (12) revealed that the two amide bond angles, α (aryl–N–C(O)) and β (N–C(O)–aryl), deviate from 120° (α ≈ 127°, β ≈ 117°), resulting in the curving of the amide linkages toward the NH side. Such slightly curved amide linkages appear to be responsible for the “opening up” of the backbone of 2b. In contrast, in two previously described systems of folding oligomers (9, 14), the backbones were rigidified by two-center intramolecular hydrogen bonds, leading to inward pointing of their amide NH groups. Consequently, much smaller (<3 Å) interior cavities were generated because of the “contraction” of the corresponding helices. The crystal structure of 2b shows that the two halves of the molecule are not identical. Deviation from the preferred planar conformation of the backbone is centered around the central isophthalamide residue: one of the two intramolecularly hydrogen-bonded 6-membered rings associated with the isophthalamide residue is significantly twisted, leading to a dihedral angle of 51° between the central ring and one of its adjacent rings. This twist around the central isophthalamide residue seems to be responsible for the large (>6 Å) pitch observed in the crystal structure of 2b. In addition, one end of the helix is also twisted, with a dihedral angle of ∼21° between the two benzene rings.

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of 2b: cylindrical bond (a), and Corey–Pauling–Koltun (CPK) (b) representations. For cylindrical bond representations, only amide hydrogens are shown for clarity of view.

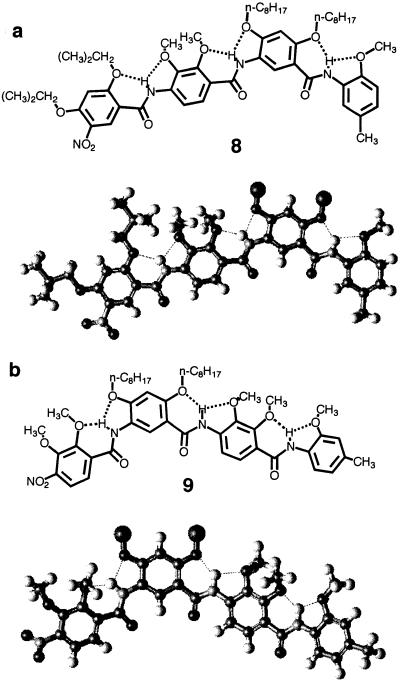

Figure 4.

Structural formulas and crystal structures of tetramers 8 (a) and 9 (b), which correspond to the four end residues of 15-mer 6 and 21-mer 7, respectively. The octyl groups are replaced with dummy atoms for clarity.

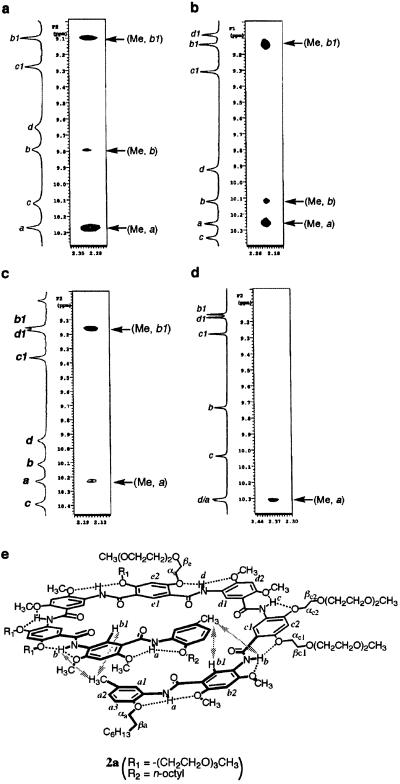

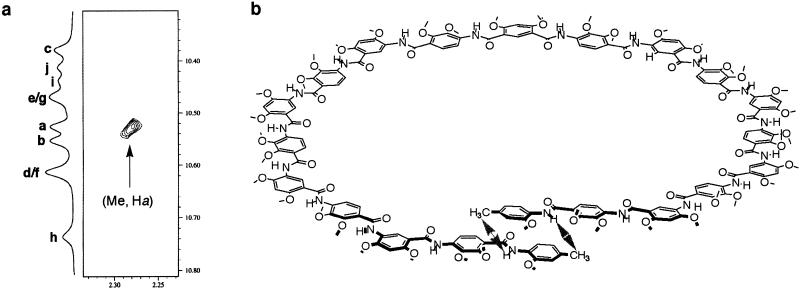

To investigate the conformation of 2a in solution, 2D NMR (NOESY, nuclear Overhauser and exchange spectroscopy) studies were carried out for 2a and the reference oligomer 3 (Fig. 3). Strong nuclear Overhauser enhancements (NOEs) exist between each of their amide NH signals and the protons of the methyl, or α/β-methylene of the two substituents on the S(5) and S(6) type hydrogen-bonded rings (see supporting information). These NOEs, which are typical for these three-center hydrogen bonds (12, 19, 20), suggest that the backbones of both 2a and 3 are rigidified and adopt crescent conformations. An obvious and significant difference is observed when comparing the NOESY spectra of 2a and 3: while an obvious NOE between the end methyl protons and the aromatic Hb1, and a weaker contact between the end methyl H atoms and the amide Hb, can be detected for 2a (Fig. 3a), the same contacts are not observed in the spectrum of 3 (Fig. 3d). These data are consistent with a helical conformation of 2a, which brings these two otherwise remote groups of protons—i.e., the end methyl and b1 protons, in close spatial proximity. As shown in Fig. 3c, the same NOE between the end methyl protons and proton Hb1 was also detected at a much shorter mixing time, and the intensity of the cross peaks reveals that the folded state is highly abundant, if not the only one present in solution. Overall, the 2D NMR data provide convincing evidence for a helical conformation of 2a in solution (Fig. 3e).

Figure 3.

(a–d) End-to-end NOEs in 2a as revealed by NOESY (500 MHz) in CDCl3 (2 mM, 263 K, mixing time 500 ms) (a), DMSO-d6/CDCl3 [1/1 (vol/vol), 2 mM, 283 K, mixing time 500 ms] (b), or DMSO-d6/CDCl3 [1/1 (vol/vol), 2 mM, 283 K, mixing time 100 ms] (c). (d) The corresponding NOEs are not observed in the reference compound 3 (CDCl3, 4 mM, 263 K, mixing time 500 ms). (e) The helical conformation of 2a and the corresponding end-to-end NOEs (arrows), along with the crescent conformation of 3.

The folded conformation of 2a also persisted in the presence of the highly polar solvent DMSO-d6, which is known to denature many biological macromolecules. As shown in Fig. 3b, the end-to-end NOE contacts (Me⋅⋅⋅Hb1 and Me⋅⋅⋅Hb) can be clearly detected in a mixed solvent with up to 50% DMSO in CDCl3. With higher percentage of DMSO-d6 in CDCl3, 2a became less soluble, preventing a 2D NMR study.

Given the localized nature of the three-center hydrogen bonds that lead to backbone rigidification, it should be possible to tune the interior cavities of the helices. By rigidifying the backbones with the same three-center hydrogen bonds while linking some of the benzene rings in a para geometry, the curvature of a backbone can be adjusted, which should lead to crescents or helices with interior cavities of larger sizes. Thus, symmetrical 15-mer 6 and 21-mer 7, each consisting of alternating residues with amide bonds placed in a meta (m-residue) or para (p-residue) relationship, were designed and synthesized.

As shown in Fig. 4, the x-ray structures of tetramers 8 and 9, which correspond to the first four end residues of 15-mer 6 and 21-mer 7, respectively, reveal backbones that are rigidified by three-center hydrogen bonds. The backbone of 8 is nearly planar, whereas that of 9 slightly deviates from planarity, probably because of crystal packing. The two methoxy methyl groups on each p-residue extend above and below the plane of the backbone to avoid congestion.

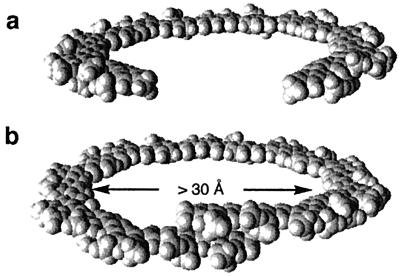

Based on values of bond lengths and angles of amide groups from the crystal structures of short oligomers, particularly those of tetramers 8 and 9, models of folded 15-mer 6 and 21-mer 7 were built (Fig. 5). Oligomer 6 is not long enough to make a full helical turn and thus can exist only as a crescent. On the other hand, 21-mer 7 makes slightly more than one turn, with about 20 residues per turn and a large interior cavity at least 30 Å across. The models predict that end-to-end NOEs may be observed for the longer 21-mer 7.

Figure 5.

Models of 6 (a) and 7 (b). All side chains of 6 and 7 are replaced with methyl groups for clarity. The backbone of 6 adopts a flat crescent conformation that can be viewed as a broken macrocycle. The backbone of 7 is long enough to fold into a helical conformation with an interior cavity >30 Å across. Models of 6 and 7 were built on the basis of the average amide bond lengths and bond angles from the crystal structures of 8 and 9.

The folding of 6 and 7 was then examined in solution by 1H NMR (750 MHz). The amide NH signals of both 6 and 7 appeared at downfield positions, between 10.1 ppm and 10.7 ppm, a range typical for amide protons involved in this type of three-center hydrogen bond (19, 20). In particular, 5 of the 7 amide NH signals of 15-mer 6 appeared as well-resolved single peaks, whereas 6 of the 10 amide NH signals of 21-mer 7 were well resolved. Additional evidence for the persistence of the intramolecular three-center hydrogen bonds in 6 and 7 came from NOESY. In the spectrum of 15-mer 6, NOEs between each of the amide protons and those (methyl and/or α/β-methylene) of neighboring side chains on both the S(5) and S(6) rings are readily identified (see supporting information on the PNAS web site for the NOESY spectra of the 11-mer 10 and its corresponding reference compound 11). Most amide signals also showed contacts with the protons of the nonadjacent methoxy groups on the p-residues. Upper distance limit constraints between amide proton and protons of neighboring methyl and/or α-methylene of the S(5) and S (6) side chains were calculated on the basis of the corresponding NOE peak volumes (see supporting information). The distance constraints involving amide protons and those of the neighboring S(5) methyl or α-methylene group range from 4.0 Å to 4.6 Å, and those involving the S(6) methyl or α-methylene groups range from 3.3 Å to 4.1 Å. These distances are in excellent agreement with those obtained from the crystal structures (Figs. 1, 2, and 4) of the shorter oligomers. The NOESY spectrum of 21-mer 7 also showed similar NOEs attributable to amide proton–side chain contacts. In both 6 and 7, the NOEs are in full agreement with a backbone that is rigidified by the three-center hydrogen bonds. A salient difference between 6 and 7 is that the spectrum of 7 revealed NOEs between the protons of the two terminal methyl groups and the two amide protons closest to the two ends (Fig. 6a). Such NOEs effectively prove the helical conformation predicted for 7 (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6.

(a) End-to-end NOEs as revealed by the NOESY spectrum of 7. (b) The helical conformation of 7 is consistent with the NOEs (indicated by arrows). All long side chains are replaced with methyl groups for clarity.

Similar NOEs were not detected for shorter oligomers such as the tetramer 9. As for the m-backbone species 2a and 3, NOESY thus shows that the 15-mer 6 and the 21-mer 7 adopt the expected folded conformations enforced by three-center hydrogen bonds.

Conclusion

We have described a general strategy for creating hollow helices with tunable nanosized cavities. A noticeable feature of these helices is that their folded conformations appear to be stable in both polar and nonpolar solvents. The extraordinary stability of the helical conformation seems to stem from the energetically favorable, but sterically hindered, three-center hydrogen bonds. The localized rigidification of amide linkages leads to a long-range order, resulting in stably folded helical conformation. An attractive attribute of this design is the large hydrophilic interior cavities generated by the folding of these molecules; cavities of such sizes are usually generated at the tertiary or quaternary structural level of proteins. An even more exciting feature of this system is the ability to tune the size of the interior cavities on the nanometer scale. Based on the highly stable intramolecular hydrogen bonds, helices with interior cavities of a variety of sizes can be prepared by adjusting the ratio of the m- and p-residues in the corresponding oligomers. The efficient amide coupling chemistry has recently allowed us to prepare longer oligomers. For example, an 11-mer consisting of the meta-linked building blocks has been found by NOESY to adopt a helical conformation of >1.6 turns (see supporting information). However, obtaining high-resolution structural data becomes increasingly difficult with even longer oligomers. These hydrophilic helical nanocavities may serve as hosts for binding ions and small molecules, particularly polar molecules such as carbohydrates and various ammonium ions. Many applications such as ion-carrier, drug-delivering vehicles, and catalysts for asymmetric transformations based on these helices can be envisaged. Finally, based on the highly efficient coupling chemistry, a straightforward extension of the established design principles involves one-pot preparation of helical polymers, leading to very long porous polymers with nanosized tubular pores. With their modifiable outside surfaces and hydrophilic tunable interior tubular cavities, these foldamers may open a new avenue for designing nanoporous polymers with unique properties.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Yang Shen for helping with the NMR data analysis involving 15-mer 6 and 21-mer 7. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the National Science Foundation, the Office of Naval Research, and the State University of New York at Buffalo. Part of the computational work was done on the University of Nebraska Research Computing Facilities computer.

Abbreviations

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- 1D and 2D

one- and two-dimensional

- NOESY

nuclear Overhauser and exchange spectroscopy

- NOE

nuclear Overhauser enhancement

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Gellman S H. Acc Chem Res. 1998;31:173–180. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowan A E, Nolte R J M. Angew Chem. 1998;37:63–68. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill D J, Mio M J, Prince R B, Hughes T S, Moore J S. Chem Rev. 2001;101:3893–4011. doi: 10.1021/cr990120t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appella D H, Christianson L A, Klein D A, Powell D R, Huang X L, Barchi J J, Gellman S H. Nature (London) 1997;387:381–384. doi: 10.1038/387381a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seebach D, Abele S, Gademann S K, Jaun B. Angew Chem. 1999;38:1595–1597. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990601)38:11<1595::AID-ANIE1595>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanessian S, Luo X H, Schaum R, Michnick S. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:8569–8570. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hintermann T, Gademann K, Jaun B, Seebach D. Helv Chim Acta. 1998;81:983–1002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu C W, Sanborn T J, Huang K, Zuckermann R N, Barron A E. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:6778–6784. doi: 10.1021/ja003154n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamuro Y, Geib S J, Hamilton A D. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:10587–10593. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bassani D M, Lehn J-M, Baum G, Fenske D. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1997;36:1845–1847. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanatani A, Hughes T S, Moore J S. Angew Chem. 2002;41:325–328. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020118)41:2<325::aid-anie325>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu J, Parra R D, Zeng H Q, Skrzypczak-Jankun E, Zeng X C, Gong B. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4219–4220. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang D, Qu J, Li B, Ng F-F, Wang X-C, Cheung K-K, Wang D-P, Wu Y-D. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:589–590. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuccia L A, Lehn J-M, Homo J-C, Schmutz M. Angew Chem. 2000;39:233–237. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(20000103)39:1<233::aid-anie233>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smith, M. D., Claridge, T. D. W., Tranter, G. E., Sansom, M. S. P. & Fleet, G. W. J. (1998) Chem. Commun., 2041–2042.

- 16.Lokey R S, Iverson B L. Nature (London) 1995;375:303–305. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koga K, Gao G T, Tanaka H, Zeng X C. Nature (London) 2001;412:802–805. doi: 10.1038/35090532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hummer G, Rasaiah J C, Noworyta J P. Nature (London) 2001;414:188–190. doi: 10.1038/35102535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parra R D, Zeng H Q, Zhu J, Zheng C, Zeng X C, Gong B. Chem Eur J. 2001;7:4352–4357. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20011015)7:20<4352::aid-chem4352>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parra R D, Gong B, Zeng X C. J Chem Phys. 2001;115:6036–6041. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernstein J, Davis R E, Shimoni L, Chang N-L. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1995;34:1555–1574. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frisch M J, Trucks G W, Schlegel H B, Scuseria G E, Robb M A, Cheeseman J R, Zakrzewski V G, Montgomery J, J A, Stratmann R E, Burant J C, et al. gaussian. Pittsburgh: Gaussian; 1998. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.