Abstract

Single cysteine-substitution mutants of KcsA, a K+ channel from Streptomyces lividans, were expressed in Escherichia coli, and inner membranes were isolated. The rate constants for the reactions of these cysteines with three maleimides of increasing hydrophobicity, 4-(N-maleimido)phenyltrimethylammonium, N-phenylmaleimide, and N-(1-pyrenyl)maleimide, were determined by back titration of the remaining cysteines with methoxypolyethylene glycol-2-pyridine disulfide (Mr 3,000) and quantitation of the fraction of gel-shifted KcsA as a function of reaction time. The patterns of the rate constants for the reactions of all three reagents with eight consecutive cysteines in the partially lipid-immersed amphipathic N-terminal tail helix were the same, with cysteines on the hydrophilic side of the helix reacting faster than Cys on the hydrophobic side. The results are consistent with the tail helix lying with its long axis in the lipid-water interface and with the orientation of the helix fluctuating around this axis. The patterns of the rate constants for the three reagents were similar to the pattern of the probabilities that the substituted cysteines were exposed to water, based on the sum of the free energies of transfer from water to octanol of all of the residues exposed to lipid in each orientation of the helix.

Identification of the surface residues in proteins provides both functional and structural information. The substituted-cysteine accessibility method, which probes engineered cysteines (Cys) with polar reagents directed to water-accessible sulfhydryls (SH), has been widely used to characterize binding sites, channels, and gates (reviewed in ref. 1). It is an indirect approach, in that the reaction of the target Cys is assayed by the resulting irreversible modification of function. Functional assays, especially electrophysiological ones, are highly sensitive and specific and are applicable to a tiny amount of target protein in a sea of other proteins. Most surface residues, however, are not directly involved in function, and reactions of most substituted Cys would not have a detectable functional effect. The general categorization of residues as facing water, facing lipid, or buried in the protein interior requires direct approaches.

A direct biophysical approach to surface residues in membrane proteins has been to express single-Cys mutants of the target protein in bacteria, purify the mutants in detergent, attach a SH-directed spin label, reconstitute the labeled protein in membrane, and analyze the mobility and susceptibility of the spin label to hydrophilic and hydrophobic quenchers (reviewed in ref. 2). These applications have either preceded a high-resolution protein structure or complemented such a structure.

Direct biochemical approaches to surface mapping are based on the assay of the reactions of single-Cys substitution mutants with hydrophilic or hydrophobic SH reagents. The reactions have been detected by incorporation of radioactive reagent initially or in a second reaction with remaining SH or, in the case of crosslinking reagents, by a decrease in the electrophoretic mobility of the target protein (3, 4). A variation of this approach is the use of reagents large enough to decrease the electrophoretic mobility of the target protein (5, 6). Maleimide and pyridine disulfide derivatives of polyethylene glycol (PEG) have been used to probe Cys and to produce large gel shifts (7). The topology of engineered Cys in a eukaryotic potassium channel expressed by cell-free translation in the presence of microsomes was probed by reaction of membrane-impermeant PEG–maleimide with the channel in microsomal membranes. Alternatively, the channel in membrane was reacted with a membrane-permeant or -impermeant reagent and then reacted in SDS with PEG–maleimide, thereby titrating the remaining Cys (8). It is this last approach that we used here.

Our motivation was to develop procedures to distinguish water-facing, lipid-facing, and interior residues in multisubunit membrane proteins like the acetylcholine receptors. Cys mutants of such proteins are expressed in heterologous cells at the picomol level. A practical biochemical method would require sensitivity at the 10- to 100-femtomol level and, because a pattern of relative reactivities of consecutive Cys is needed to infer secondary structure, would also require sufficient precision to yield rate constants. To develop sensitive and precise methods and to test different reagents, we characterized the reactions of three maleimide derivatives of increasing hydrophobicity with Cys mutants of KcsA, a proton-gated K+ channel (9, 10) found in Streptomyces lividans (11). KcsA is a homotetramer of a 160-residue monomer (12, 13). The structure from residue 23 to 119 was solved to high resolution (14, 15). The structures of the N-terminal residues 1–22, which were disordered in the crystal, and of the C-terminal 35 residues, which were cleaved before crystallization, were determined by EPR analysis of spin-labeled Cys-substitution mutants (16) (Fig. 1).

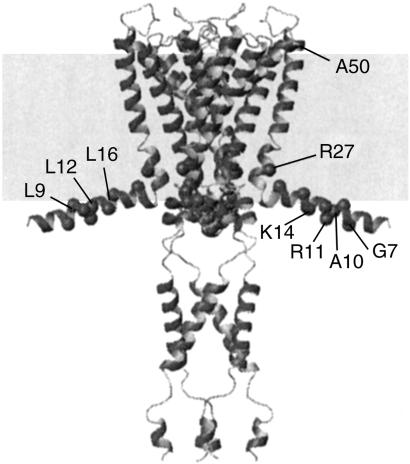

Figure 1.

Structure of KcsA in membrane. The structure of the core is from the x-ray crystal structure (14), and the structures of the N- and C-terminal tails are based on spin-labeling studies (16). The gray box represents the membrane bilayer. The extracellular side is up.

We determined the rate constants for the reactions of positively charged, hydrophilic 4-(N-maleimido)phenyltrimethylammonium (MPTA) and two reagents of increasing hydrophobicity, N-phenylmaleimide (PheM) and N-(1-pyrenyl)maleimide (PyrM), with consecutive Cys substituted in the amphipathic N-terminal tail helix and in the first membrane-spanning helix (TM1) of KcsA in Escherichia coli membrane. In the tail helix, all three reagents reacted faster with Cys facing water than with Cys facing lipid. The similarity of the patterns of the rate constants for the reactions of all three reagents with Cys in the tail helix is consistent with all of the substituted Cys reacting only when exposed to water. A similar conclusion was reached about the reactions of disulfide reagents with single-Cys mutants of diacylglycerol kinase in detergent (17).

Materials and Methods

Dodecyl maltoside (DM) was obtained from Anatrace (Maumee, OH); PyrM, from Sigma; PheM, from Aldrich; methoxypolyethylene glycol-2-pyridine disulfide Mr 3,000 (PegSSP), from Shearwater Polymers (Huntsville, AL); DNase I code DPRF from Worthington; pepstatin and leupeptin, from Roche Diagnostics; phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, from Sigma; Ni(II)-nitrilotriacetate-agarose, from Qiagen (Chatsworth, CA); and Sypro Orange, from Molecular Probes. MPTA was synthesized as in ref. 18.

The sequence of the 173-residue-long pseudowild-type KcsA construct used here begins M−13RGSHHHHHHGIR−1-M1PPMLS6GLLAR11LVKLL16LGRHG21SALHW26RAAGA31-ATVLL36VIVLL41, in which residues –13 to –1 contain a His-tag, and the native sequence starts at M1. The single-Cys substitution mutants at positions 7–14 in the tail helix and 33–39 in TM1 were generated and expressed in E. coli as previously described (16, 19).

Membrane Preparation.

Two hours after isopropylthiogalactoside induction, the bacteria from a 500-ml culture were collected and washed in PBS and suspended in 10 ml of 20% sucrose/10 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0)/235 units DNase I/ml/1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride/0.3 μg of leupeptin/ml/0.3 μg of pepstatin/ml. All steps were at 4°C. The suspension was passed three times through an EmulsiFlex C-5 High Pressure Homogenizer (Avestin, Ottawa) at 15,000–20,000 psi. After sedimentation at 12,000 × g for 20 min, 4°C, the supernatant (9–10 ml) was layered on a step gradient of 14 ml of 60% (wt/vol) sucrose/10 mM NaPi (pH 7.0) over 14 ml of 70% (wt/vol) sucrose/10 mM NaPi (pH 7.0) and centrifuged in a Beckman SW28.1 rotor at 23,000 rpm, 16 h, 4°C. Inner membranes were collected at the 20–60% sucrose step, diluted three times with water, and sedimented in a Beckman 60Ti rotor at 60,000 rpm for 1 h at 4°C. The membranes were suspended in 1 ml of 0.3 M sucrose and stored in liquid nitrogen.

The concentration of KcsA in membrane was determined by extracting and purifying KcsA from an aliquot of each preparation: 100 μl of membrane and 100 μl of 2% DM/200 mM NaCl/100 mM NaPi (pH 8.0) were stirred for 1 h at room temperature (rt). The mixture was sedimented in a Beckman Airfuge at 100,000 rpm for 3 min. The supernatant (≈200 μl) and 200 μl of 1:1 suspension of Ni(II)-nitrilotriacetate-agarose in 100 mM NaCl/50 mM NaPi (pH 8.0) (100N50P) were stirred for 1 h at rt. The gel was washed twice with 1 ml of 20 mM imidazole/0.5% DM/100N50P and eluted twice with 400 μl of 400 mM imidazole/0.5% DM/100N50P by stirring for 1 h and sedimentation. The concentration of KcsA in the combined supernatants was determined as A280/1.84 mg/ml (12). The membrane contained mutant KcsA at concentrations from 0.3 to 1.3 mg/ml. Total protein was 3.4–5.7 mg/ml, determined by the BCA assay (Pierce). KcsA was 7–27% of total membrane protein.

Results and Discussion

Extent of Reaction.

We stirred maleimide and membrane containing His-tagged KcsA for a given time, stopped the reaction with 2-mercaptoethanol (2ME), solubilized the membrane in SDS, dissociated the tetrameric KcsA at 100°C, and reacted the remaining Cys SH with PegSSP, which specifically forms a mixed disulfide. To isolate KcsA and KcsA-SSPeg from the other components of the E. coli membrane (and from excess PegSSP, which interfered with electrophoresis), we diluted the SDS with DM and bound the His-tagged KcsA to Ni(II)-nitrilotriacetate-agarose. KcsA and KcsA-SSPeg were eluted in EDTA/2% SDS, separated by SDS/PAGE, and quantitated by Sypro Orange staining (Fig. 2). This method yielded highly reproducible results when 10–20 pmol total KcsA was loaded per gel lane. Detection by Western blotting was two to three orders of magnitude more sensitive but was less reproducible.

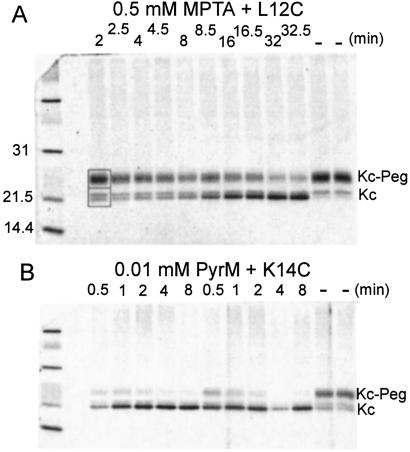

Figure 2.

Reaction of L12C with MPTA and K14C with PyrM detected by the subsequent reaction with PegSSP and a mobility shift. (A) Membrane containing 45 μg of L12C was stirred in 62 μl of 10 mM DTT/160 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.0, for 1 h at rt under argon. The DTT was removed by dilution to 200 μl with cold HE buffer (20 mM Hepes/0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.0), sedimentation in a Beckman Airfuge at 160,000 × g for 3 min, suspension of the pellet in 200 μl of cold HE buffer, sedimentation as before, and suspension in 300 μl of cold HE buffer. Membrane (240 μl) and 10 μl of 12.5 mM MPTA in water were stirred at rt, 20 μl was removed at the times indicated, and the reaction was stopped with 2 μl of 15.4 mM 2ME; 2 μl of 10% SDS was added, and the mixture was held at 100°C for 3 min. PegSSP (24 μl of 20 mM in 100 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.0) was added and the mixture stirred at rt for 45 min. This reaction was stopped with 2 μl of 50 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM). To this mixture was added 0.5 ml of 1% DM in NP buffer (100 mM NaCl/50 mM NaPi, pH 8.0); and 30 μl of Ni(II)-nitrilotriacetate-agarose gel, 1:1 suspension in NP buffer, and the mixture was stirred at rt for 60 min. The gel was sedimented and washed with 1 ml of 0.3% DM/NP buffer and 1 ml of water. The His-tagged KcsA was eluted from the gel by stirring 15 min in 30 μl of 5 mM EDTA/2% SDS/62.5 mM Tris (pH 6.8)/10% glycerol (LSB), sedimenting the gel and recovering the supernatant, and repeating this step with another 30 μl of EDTA/LSB. To the combined supernatants was added 1 μl of 0.05% Pyronin Y and two 20 μl of aliquots, each containing ≈0.5 μg of KcsA, were run on duplicate (one shown) 15-well polyacrylamide minigels (2.6% stacking gel/14% resolving gel). The running buffer contained 0.05% SDS/25 mM Tris base/200 mM glycine, pH 8.3. After electrophoresis, the gels were agitated for 60 min in 1:5,000 dilution of Sypro Orange in 7.5% acetic acid, washed for 1 min in 7.5% acetic acid, and scanned in a Storm 840 (Molecular Dynamics) in fluorescence mode. The intensity of the fluorescent bands was quantitated with imagequant software (Molecular Dynamics). The integrated fluorescence intensities within a rectangle enclosing the lower doublet and another rectangle enclosing the upper PegSSP-modified KcsA (typical rectangles shown for the 2-min lane) were determined. No MPTA was added to the duplicate samples on the far right, which were otherwise treated as the 32-min samples. Low-range-molecular-weight standards (Bio-Rad) were run in the far left lane. (B) In a variation on the procedure in A, 37 μg of K14C was reduced in 125 μl of 10 mM DTT. After 1 h, the membrane was diluted and sedimented twice in 400 μl of HE buffer and suspended in 300 μl of HE buffer. Membrane (120 μl) was mixed with 5 μl of 250 μM PyrM in methanol, and 20-μl aliquots were taken at the indicated times and treated exactly as in A. In this case, however, a second set of aliquots at the same time intervals were taken from a duplicate reaction mixture.

The reaction of the Cys mutants with PegSSP resulted in an increase in the apparent molecular weight of KcsA of about 3,000. The extent of reaction with PegSSP of the mutants after reduction ranged from 30 to 80% of the total monomeric KcsA. Wild-type KcsA, which is Cys-less, was unaffected by PegSSP. Although monomeric wild-type KcsA and L36C through V39C in TM1 ran as single bands on SDS/PAGE, all tested Cys mutants in the tail and the Cys mutants in TM1 at positions 33, 34, and 35 ran as closely spaced doublets, even after rigorous reduction with DTT or Tris-(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine and Tris-(2-cyanoethyl)phosphine. Only the lower band of the doublet reacted with PegSSP (Fig. 2).

MPTA was added to membrane in water, but PyrM, which is poorly soluble in water (Table 1), was added in methanol. The reported rate constants for the reactions of PyrM were all obtained at a final nominal concentration of PyrM of 10 μM and 4% methanol. For the mutants tested, the rate constants were the same over the range of nominal concentrations of 5–25 μM; in all cases, the actual concentration of PyrM in the aqueous phase was the same, ≈1 μM (Table 1). Furthermore, methanol over the range of concentrations of 2–10% did not affect the kinetics of the reaction of V13C with either PyrM or MPTA. The kinetic data for PheM were obtained at concentrations from 50 to 1,000 μM, in 5% methanol.

Table 1.

Properties of maleimides

| Maleimide | Aqueous solubility, mM | Partition coefficient CHCl3:H2O | Reactant | Reaction solvent | Rate constant, 1/M/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPTA | >50 | 5.6(±0.06) × 10−4 | Cys | Ringers buffer | 8,850 ± 680 (18) |

| NEM | ∼100 | ND | Cys | Ringers buffer | 1,620 ± 130 (18) |

| MPTA | 2ME | HEM buffer | 1,140 ± 110 | ||

| PheM | >3 | ND | 2ME | HEM buffer | 600 ± 250 |

| PyrM | ≈0.001 | 2.8(±0.2) × 104 | 2ME | HEM buffer | 2,400 ± 145 |

| PyrM | 2ME | CHCl3:CH3OH(1:1) | 0.4 ± 0.15 |

Aqueous solubility is the highest concentration we were able to make. The concentration of PyrM in water was estimated by absorbance at 338 nm (ɛ338 = 24,000). The partition coefficient of MPTA was determined by vigorous mixing of 0.5 ml of 20 mM MPTA in water with 9 ml of CHCl3. An aliquot of the CHCl3 phase was equilibrated with reduced glutathione in HE buffer, and the change in glutathione SH was assayed with 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) (20). The partition coefficient of PyrM was determined by equilibrating 3 ml of 1.5 mM PyrM in CHCl3 with 3 ml of water. To 1.8 ml of the aqueous phase was added 0.2 ml of 10% SDS/200 mM HEPES/2 mM EDTA, pH 7.4. The fluorescence intensity (excitation, 338 nm; emission, 375 nm) was determined before and after the addition of 10 μl of 200 mM 2ME. Similarly, 2 μl of the CHCl3 phase was added to 200 μl of 10% SDS buffer and 1.8 ml of water, and the fluorescence was determined before and after the addition of 10 μl of 200 mM 2ME. PyrM is fluorescent only after reaction of the maleimide double bond (21). The ratio of the net fluorescence intensities from the two phases, determined under the same final conditions, after multiplying by the dilution factors, gave the partition coefficient. The rate constant for the reaction of 0.5 μM PyrM and 1 μM 2ME in 40 mM Hepes (pH 7.4) 1 mM EDTA 1% methanol (HEM buffer) was determined from the time course of the fluorescence increase. The rate constant for the reaction of 1 mM 2ME and 0.85 mM PyrM in CHCl3:CH3OH (1:1) was determined by taking 50-μl aliquots at various time, diluting with 950 μl of 0.2 mM DTNB/200 mM Tris (pH 8.0), mixing, centrifuging to separate the CHCl3, and reading A412 of the supernatant. The data were fit by equations for second-order reaction kinetics. The rate constants for the reactions of PheM and MPTA with 2ME were determined by competition with the reaction of PyrM, according to the equation kB/kA = ln[(b0 − c0 + pinf)/b0]/ln[(a0 − pinf)/a0], where A refers to PyrM and B to a competing maleimide; a0, b0, and c0 are the initial concentrations of PyrM, competing maleimide, and 2ME, respectively; and pinf is the concentration of the PyrM-2ME adduct at completion of the reaction. The initial conditions are that a0 and b0 are greater than c0. A reaction run without competing maleimide and a0 > c0 gives pinf = c0, and this c0 divided by the fluorescent change is used to convert the final fluorescent change in the competition reaction to pinf. Typically, a0 = 0.5 μM, b0 = 0.5 μM, and c0 = 0.4 M. All determinations were at ≈22°C. Ringers buffer contained 165 mM NaCl, 2.3 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, and 1.5 mM KPi (pH 7.0). Rate constants for reactions with 2ME at pH 7.4 were extrapolated to pH 7.0 (22). ND, not determined.

Kinetics.

Typically, samples were taken at 10 different times from a single reaction mix (Fig. 2A) or at five times from duplicate reaction mixes (Fig. 2B). The zero-time point was obtained from a sample stirred for the duration of the reaction but in the absence of maleimide (the duplicate last two lanes in Fig. 2 A and B), the fraction of total KcsA that was converted to the slower moving KcsA-SSPeg [i.e., Kc-Peg/(Kc-Peg + Kc) in Fig. 2] was the maximum fraction of KcsA Cys that could react with PegSSP. With increasing time of reaction with maleimide, the fraction of the total KcsA that was in the KcsA-SSPeg band decreased, and the fraction in the faster moving KcsA band increased (Fig. 2). Each lane determined an extent of reaction independently of the total recovery of KcsA. The means of two to four points at each reaction time had quite small errors, as did the fits of the kinetic equation (Fig. 3). A limitation of the method was that reaction times shorter than 30 s were not practical because of the time required to take an aliquot and to stop the reaction with 2ME. Also, the concentration of maleimide could not be too low because of its possible consumption by residual DTT from the reduction step and by other SH present in the membrane. Nevertheless, all rate constants were obtained with fair precision (Fig. 3).

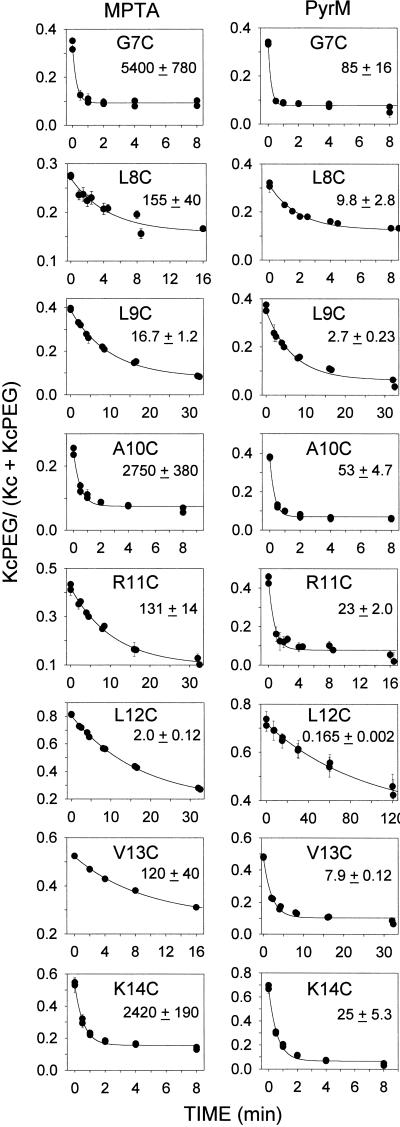

Figure 3.

Kinetics of PyrM and MPTA reacting with eight KcsA Cys mutants. The MPTA reactions are on the left and the PyrM reactions are on the right. The fraction of Cys remaining at each time point (i.e., not yet reacted with maleimide) was determined in each lane as the integrated fluorescent intensity of the KcsA-PegSSP band divided by the sum of the intensities of the KcsA-PegSSP band and the KcsA band. Two sets of averages of duplicate lanes (and average errors) are plotted; the error bars in some cases are smaller than the symbol. The curves are nonlinear-least-squares fits of ae−bt + c to the data. For the reactions of MPTA, the second-order rate constants are given in units of 1/M/s; for PyrM, the pseudofirst-order rate constants are given in units of 1/1,000s.

The rate constants were obtained from the nonlinear least-squares fit to the data of the equation, a*exp(−bt) + c (Fig. 3). The second-order rate constants, k, for MPTA and PheM were obtained by dividing the pseudofirst-order rate constants, b, by the concentrations of maleimide in the aqueous phase. The concentration of PyrM, although identical in all cases, was known only approximately. To convert b to k for PyrM, we assumed that the rate constant for its reaction with G7C was four times the rate constant for the reaction of PheM with G7C, just as PyrM reacted four times faster than PheM with 2ME in solution (Table 1). Thus, the effective concentration of PyrM reacting with G7C would have been bPyrM/(4kPheM) = 0.085/4*560 = 37.9 μM. Taking this as the effective PyrM concentration at all mutants, we obtain the kPyrM (Fig. 4A).

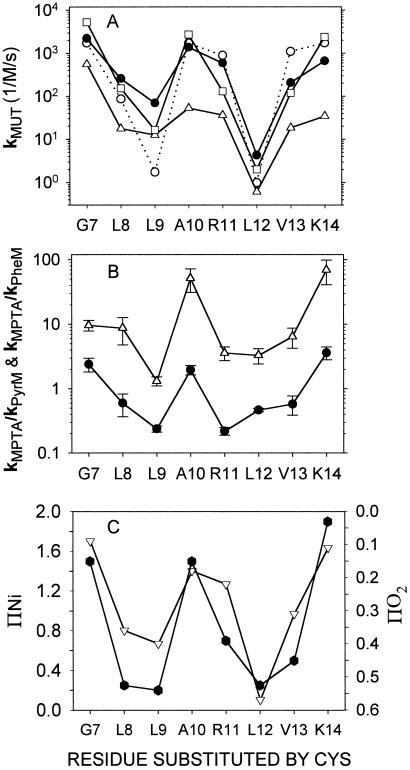

Figure 4.

Rate constants for the reactions of MPTA, PheM, PyrM with the tail Cys mutants. (A) The rate constants for MPTA (unfilled squares) and for PheM (unfilled triangles) are second-order rate constants, as determined. For PyrM (filled circles), the pseudofirst-order rate constants were obtained at the same nominal total PyrM concentration (10 μM), and these were converted to second-order rate constants by dividing the first-order rate constants by 37.9 μM (see text). Also shown is the theoretical probability (see Fig. 5) that each substituted Cys faces water (unfilled circles) divided by the probability that the Cys substituted for L12 faces water, assuming that residues 1–17 comprise the tail helix. (B) The rate constant for the reaction of each mutant with MPTA divided by the rate constant for the reaction with PyrM (filled circles) or divided by the rate constant for the reaction with PheM (open triangles). (C) The Ni(II) ethylenediaminediacetate (NiEDDA)-accessibility parameter ΠNi (filled hexagons) and the O2-accessibility parameter ΠO2 (unfilled triangles) (16). The latter parameter is plotted from high to low, so that its minima correspond to the maxima of the NiEDDA-accessibility parameter, which are at the most water-accessible residues.

If PyrM had reacted at its concentration in the bulk aqueous phase of ≈1 μM, the rate constant would have been improbably high. Rather, it is likely that PyrM partitions into the lipid-water interface with the pyrene moiety in the lipid bilayer and with the maleimide moiety in the aqueous phase, where it can react with interfacial Cys. In addition, given the partition coefficient of PyrM between water and nonpolar solvent (Table 1), the concentration of PyrM completely buried in the bilayer is likely to be high, but its reactivity there is low.

The rate constants for all three maleimides follow the same pattern (Fig. 4A). (The pattern for PyrM is independent of whether we plot b or the calculated k.) The rate constants were greater for G7C, A10C, R11C, and K14C than for L8C, L9C, L12C, and V13C, except that MPTA reacted slightly faster with L8C than with R11C (Figs. 3 and 4A). The more reactive Cys were replacements for residues on the water-facing side of the tail helix, and the less reactive Cys were replacements for residues on the lipid-facing side of the tail helix (Figs. 1 and 4C) (16). The rate constants for the reactions of G7C, the most reactive Cys, with MPTA, PheM, and PyrM were respectively 2,600, 900, and 500 times the rate constants for the reactions with L12C, the least reactive Cys.

Small to moderate differences among the maleimides in their preferences for water-exposed Cys compared with lipid-exposed Cys were reflected in the ratios of the rate constants, MPTA to PyrM and MPTA to PheM (Fig. 4B). These ratios peak at G7C, A10C, and K14C, consistent with the exposure of the native residues. These ratios, just as the rate constants themselves, correspond to exposures implied by the quenching by lipophilic O2 and hydrophilic Ni(II) ethylenediaminediacetate of the spin-labeled Cys (Fig. 4C) (16).

It was surprising to us that the patterns of reactivity were approximately the same for the charged MPTA and for the hydrophobic PyrM. At the same concentrations in the aqueous phase, the PyrM concentration in the lipid phase would be several orders of magnitude greater than the MPTA concentration (Table 1). Also, the reactivity of PyrM was greater than that of MPTA with 2ME in aqueous buffer (Table 1). Nevertheless, PyrM reacted only slightly faster with lipid-facing Cys than did MPTA (Fig. 4A).

In addition, PyrM reacted very slowly with Cys in TM1. The rate constants for the reactions of PyrM with T33C, V34C, and L35C were 5,000–10,000 times smaller than the rate constant for the reaction with G7C, and even deeper into the bilayer the reactions at L36C, V37C, I38C, and V39C were too slow to detect over a 2-h reaction time. Also, PyrM was previously reported to react very slowly with substituted Cys in the membrane-spanning proteolipid of vacuolar H+-ATPase (23).

Like methanethiosulfonates (24), maleimides react many orders of magnitude faster with ionized thiolates than with unionized thiols (22), and ionization is suppressed in a nonpolar environment. For example, the rate constant for the reaction of PyrM with 2ME in chloroform–methanol is 6,000 times smaller than the rate constant in aqueous buffer (pH 7.0) (Table 1). The reaction of PyrM in the lipid bilayer, less polar than chloroform-methanol and more viscous, is likely to be much slower.

Rolling Helix Model.

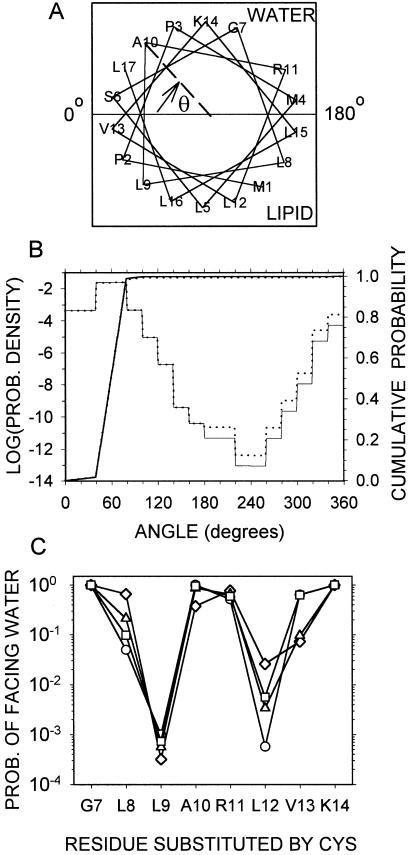

The very low reactivity of Cys in a nonpolar environment, and the similarity of the patterns of reactivity of the hydrophilic MPTA and the hydrophobic PyrM suggest that the reactions with the tail Cys are almost exclusively with the Cys while it is exposed to water. Fluctuations in the structure or orientation of the tail helix could expose its residues to water. A simple possibility is that the tail helix lies with its long axis in the plane of the lipid-water interface and that it rotates around this axis (Fig. 5A). This model simplifies the orientation of the helical axis, which may enter the membrane at a shallow angle (16). For each mutant, we can calculate the free energy of each rotational orientation of the helix and the probability that the substituted Cys is exposed to water (Fig. 5 B and C). We treat the tail helix as an ideal α-helix with 100° between simplified side chains. The probability, pθ,k, that the kth side-chain will be in the sector θ to θ + δ is

|

|

|

|

where n is the number of residues in the helix, i is the residue position in the sequence, and μi(φ) is the free energy/mol of the ith residue, which is a function of its argument, φ:

Figure 5.

Rolling-helix model. (A) Helical wheel representation of residues 1–17 with the helical axis in the plane of the water-lipid interface and showing the angle θ from the interface to Ala-10, measured clockwise. For 0° ≤ θ < 180°, the residue faces water, and for 180° ≤ θ < 360°, the residue faces lipid. (B) Probabilities (see text) that Ala-10 (light solid line) and the Cys substituted for Ala-10 (light dotted line) are in the sector θ to θ + 1°, and cumulative probabilities that Ala-10 (heavy solid line) and the Cys substituted for Ala-10 (heavy dotted line) are in the sector from 0° to θ°. (C) The probabilities that the substituted Cys face water, assuming that the tail helix includes residues 1–17 (circles); 1–20 (squares); 5–17 (triangles); 5–20 (diamonds).

μi(φ) = 0 for 0° ≤ φ < 180°; i.e., for the ith residue facing water;

μi(φ) = ΔGobs(water → octanol) for 180° ≤ φ < 360°; i.e., for the ith residue facing lipid (25).¶ In the Cys substitution mutants, the kth residue is Cys, for which we take ΔG(water → octanol) = 1.34 kcal/mol, the value for cystine/2.

In the equation for Qk, S, the upper limit for j, is 360/δ−1, so that the angular sectors for the kth residue start at the values 0, δ, 2δ, … , 360−δ, and the angles of all other residues are calculated by adding (i−k)*100° and taking the positive remainder after dividing by 360; i.e., mod 360.

The probability that the kth residue faces water is

|

where U = 180°/δ−1; i.e., the cumulative probability over the interval 0–180°. The calculated probabilities were the same with angular increments, δ = 0.5° and 1°. Because the residues projected on the base in an ideal α-helix are multiples of 20° apart (Fig. 5A), changes in exposure to water or lipid occur only at multiples of 20° of rotation, and therefore the probability density of the rotation angle is constant over intervals of multiples of 20° (Fig. 5B).

The orientation probabilities of a wild-type residue and of the Cys substituted for it are different if ΔG(water → octanol) is different for the two side chains. As an example, Cys substituted for A10 is slightly more likely to be facing lipid than is A10: the probabilities in the lipid-exposed sectors are greater, and the rise in the cumulative probability from 180° to 360° is greater (Fig. 5B).

The extent of the N-terminal tail helix is uncertain. The spin labeling results obtained for residues 5–25 were consistent with a helix starting at residue 5 and ending between residues 17 and 20 (16). We have calculated the probability of Cys-facing water for tail segments, 1–17, 1–20, 5–17, and 5–20 (Fig. 5C). Although the patterns are similar, the probabilities for residues 1–17, like the observed rate constants, reach an absolute minimum at L12C (Figs. 4A and 5C).

Ratios of two to three orders of magnitude in rates of reaction allow categorization of Cys as either water-exposed or buried, but Cys with intermediate rates of reaction can be difficult to categorize individually on this basis, as can be seen by comparing the rates of reaction with MPTA of L8C, R11C, and V13C (Fig. 4A). Although the charged R11 is certainly exposed to water, the shorter and more hydrophobic Cys side chain in R11C could be less so. Even the spin-labeled R11C was less accessible to the hydrophilic quencher Ni(II) ethylenediaminediacetate than the spin-labeled A10C (Fig. 4C). The pattern of reactivity of the substituted Cys, just like the pattern of quenching of the spin-labeled Cys, however, clearly reflects the partial immersion of the amphipathic tail helix in the bilayer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mary Chalmers for technical assistance; Carol Deutsch for sharing data before publication and for comments on the manuscript; and Jonathan Javitch, H. Ronald Kaback, and An-suei Yang for advice and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Research Grant NS07065 to A.K.

Abbreviations

- Cys

cysteine(s)

- DM

dodecyl maltoside

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- KcsA

K+ channel from S. lividans

- 2ME

2-mercaptoethanol

- MPTA

4-(N-maleimido) phenyltrimethylammonium

- PegSSP

methoxypolyethylene glycol-2-pyridine disulfide Mr 3,000

- PheM

N-phenylmaleimide

- PyrM

N-(1-pyrenyl)maleimide

- SDS

sodium dodecylsulfate

- SH

sulfhydryl

- rt

room temperature

Footnotes

|

References

- 1.Karlin A, Akabas M H. In: Methods in Enzymology. Conn P M, editor. Vol. 293. San Diego: Academic; 1998. pp. 123–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hubbell W L, Cafiso D S, Altenbach C. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:735–739. doi: 10.1038/78956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler S L, Falke J J. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10746–10756. doi: 10.1021/bi980607g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frillingos S, Sahin-Toth M, Wu J, Kaback H R. FASEB J. 1998;12:1281–1299. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.13.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker B, Bayley H. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23065–23071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.23065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones P C, Sivaprasadarao A, Wray D, Findlay J B. Mol Membr Biol. 1996;13:53–60. doi: 10.3109/09687689609160575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Movileanu L, Cheley S, Howorka S, Braha O, Bayley H. J Gen Physiol. 2001;117:235–238. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu J, Deutsch C. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13288–13301. doi: 10.1021/bi0107647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuello L G, Romero J G, Cortes D M, Perozo E. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3229–3236. doi: 10.1021/bi972997x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heginbotham L, Kolmakova-Partensky L, Miller C. J Gen Physiol. 1998;111:741–749. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.6.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schrempf H, Schmidt O, Kummerlen R, Hinnah S, Muller D, Betzler M, Steinkamp T, Wagner R. EMBO J. 1995;14:5170–5178. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cortes D M, Perozo E. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10343–10352. doi: 10.1021/bi971018y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heginbotham L, LeMasurier M, Kolmakova-Partensky L, Miller C. J Gen Physiol. 1999;114:551–560. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.4.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doyle D A, Morais Cabral J, Pfuetzner R A, Kuo A, Gulbis J M, Cohen S L, Chait B T, MacKinnon R. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Y, Morais-Cabral J H, Kaufman A, MacKinnon R. Nature (London) 2001;414:43–48. doi: 10.1038/35102009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cortes D M, Cuello L G, Perozo E. J Gen Physiol. 2001;117:165–180. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.2.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Czerski L, Sanders C R. FEBS Lett. 2000;472:225–229. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karlin A, Winnik M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;60:668–674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.60.2.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perozo E, Cortes D M, Cuello L G. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:459–469. doi: 10.1038/nsb0698-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riddles P W, Blakeley R L, Zerner B. Anal Biochem. 1979;94:75–81. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90792-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weltman J K, Szaro R P, Frackelton A R, Jr, Dowben R M, Bunting J R, Cathou B E. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:3173–3177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorin G, Martic P A, Doughty G. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1966;115:593–597. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(66)90079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrison M A, Murray J, Powell B, Kim Y I, Finbow M E, Findlay J B. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25461–25470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roberts D D, Lewis S D, Ballou D P, Olson S T, Shafer J A. Biochemistry. 1986;25:5595–5601. doi: 10.1021/bi00367a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisenberg D, McLachlan A D. Nature (London) 1986;319:199–203. doi: 10.1038/319199a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]