Abstract

The most widely distributed dinoflagellate plastid contains chlorophyll c2 and peridinin as the major carotenoid. A second plastid type, found in taxa such as Karlodinium micrum and Karenia spp., contains chlorophylls c1 + c2 and 19′-hexanoyloxy-fucoxanthin and/or 19′-butanoyloxy-fucoxanthin but lacks peridinin. Because the presence of chlorophylls c1 + c2 and fucoxanthin is typical of haptophyte algae, the second plastid type is believed to have originated from a haptophyte tertiary endosymbiosis in an ancestral peridinin-containing dinoflagellate. This hypothesis has, however, never been thoroughly tested in plastid trees that contain genes from both peridinin- and fucoxanthin-containing dinoflagellates. To address this issue, we sequenced the plastid-encoded psaA (photosystem I P700 chlorophyll a apoprotein A1), psbA (photosystem II reaction center protein D1), and “Form I” rbcL (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase) genes from various red and dinoflagellate algae. The combined psaA + psbA tree shows significant support for the monophyly of peridinin- and fucoxanthin-containing dinoflagellates as sister to the haptophytes. The monophyly with haptophytes is robustly recovered in the psbA phylogeny in which we increased the sampling of dinoflagellates to 14 species. As expected from previous analyses, the fucoxanthin-containing dinoflagellates formed a well-supported sister group with haptophytes in the rbcL tree. Based on these analyses, we postulate that the plastid of peridinin- and fucoxanthin-containing dinoflagellates originated from a haptophyte tertiary endosymbiosis that occurred before the split of these lineages. Our findings imply that the presence of chlorophylls c1 + c2 and fucoxanthin, and the Form I rbcL gene are in fact the primitive (not derived, as widely believed) condition in dinoflagellates.

One of the most intriguing stories in plastid evolution is found in the dinoflagellate algae. This diverse, predominantly unicellular group is characterized by having one transverse and one longitudinal flagellum and a distinct layer that lies beneath the cell membrane (the amphiesma). Only about one-half of dinoflagellates are photosynthetic and many of these species are mixotrophic (1). Some heterotrophic dinoflagellates have acquired a temporary plastid in their cytoplasm (2). Others, such as Symbiodinium spp., are themselves endosymbionts of corals (3). Regardless of trophic condition, the dinoflagellates are an important component of marine ecosystems as symbionts and primary producers, and as the main source of toxic red tides (1, 4).

Photosynthetic dinoflagellates contain several types of plastids. The most common type is a 3-membrane bound plastid that contains chlorophyll c2 with peridinin as the main carotenoid (5, 6). Secondary endosymbiosis, in which a photosynthetic eukaryote (in this case, a red alga) was engulfed by a nonphotosynthetic protist, is widely accepted as the origin of this plastid (7–11). Peridinin is believed to have evolved in the plastid of the ancestral dinoflagellate, with other plastid types being subsequent replacements of this organelle through tertiary (the uptake of an alga containing a secondary endosymbiont) endosymbiosis (11). A second type of plastid found in Karenia brevis (as Gymnodinium breve), Karenia mikimotoi (as Gymnodinium mikimotoi), and Karlodinium micrum (as Gymnodinium galatheanum) (12) is surrounded by three membranes and contains chlorophylls c1 + c2 and 19′-hexanoyloxy-fucoxanthin and/or 19′-butanoyloxy-fucoxanthin, but lacks peridinin (6, 13, 14). These taxa are believed to be monophyletic, and their plastid is believed to have originated from a haptophyte alga through a tertiary endosymbiosis in their common ancestor (15). Haptophyte algae are primarily unicellular marine taxa that have external body scales composed of calcium carbonate known as coccoliths, two anterior flagella, and plastids surrounded by four membranes. Haptophyte plastids also contain chlorophylls c1 + c2 and fucoxanthin (6). Tertiary endosymbiosis explains the origin of the plastid in several other dinoflagellates: cryptomonad-like plastid (i.e., Dinophysis acuminata; ref. 16), diatom-like plastid (i.e., Peridinium foliaceum; refs. 17 and 18), and prasinophyte-like plastid (i.e., Lepidodinium viride; ref. 19). Like Karlodinium and Karenia, all dinoflagellates containing anomalous plastids are thought to trace their ancestry to a peridinin-containing common ancestor (10, 15). A single study using limited photosystem II reaction center protein D1 (psbA) data has suggested otherwise, i.e., that both fucoxanthin and peridinin dinoflagellates may share a single plastid ancestor, although no haptophytes were included in this analysis (20).

The idea that plastids with fucoxanthin are the result of a replacement of the secondary, peridinin-containing plastid in Karenia and Karolodinium has yet to be rigorously tested by using phylogenies that contain sequence data from both types of plastids. To address this gap in our knowledge, we sequenced 36 psaA (photosystem I P700 chlorophyll a apoprotein A1), 36 psbA, and 23 “Form I” rbcL (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase) plastid-encoded coding regions from various red and dinoflagellate algae. These sequences were analyzed to infer a phylogeny with both peridinin- and fucoxanthin-containing dinoflagellate plastids in a context of broad taxon sampling.

Materials and Methods

Algal Cultures and Sequencing.

The algal cultures were obtained from the Culture Collection of Algae and Protozoa (CCAP; Dunbeg, United Kingdom), Provasoli-Guillard National Center for Culture of Marine Phytoplankton (CCMP, West Boothbay Harbor, ME), the Sammlung von Algenkulturen (SAG) at the University of Göttingen (Göttingen, Germany), and the Culture Collection of Algae at the University of Texas at Austin (UTEX). Some of Cyanidiales red algae were collected in the field and maintained at the Dipartimento di Biologia Vegetale (DBV) culture collection at the University of Naples, Italy. Chondrus crispus and Palmaria palmata were collected from Nova Scotia and Maine. The species, strain numbers and collection sites of these taxa are listed in Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org. The algal cultures were frozen in liquid nitrogen, and ground with glass beads by using a glass rod and/or MiniBeadBeater (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK). Total genomic DNA was extracted by using the DNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). PCRs were done by using specific primers for each of the plastid genes (Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The presence of highly variable third codon positions in the psaA gene led us to use species-specific primers based on sequences in sister species. Because introns were found in the psaA gene of some red algae, the reverse transcription (RT)-PCR method was used to isolate cDNA. For the RT-PCR, total RNA was extracted by using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). To synthesize cDNA from total RNA, Moloney murine leukemia virus Reverse Transcriptase (GIBCO/BRL) was used following the manufacturer's protocol. PCR products were purified by using the QIAquick PCR Purification kit (Qiagen), and were used for direct sequencing with the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems), and an ABI-3100 at the Center for Comparative Genomics at the University of Iowa. Some PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T vector (Promega) before sequencing.

Phylogenetic Analyses.

Sequences were manually aligned by using seqpup (21). The data sets used in the phylogenetic analyses are available from D.B. In the first analysis, we used a collection of concatenated psaA and psbA genes that contained 22 rhodophytes, 4 cryptophytes, 7 haptophytes, 4 stramenopiles, 7 dinoflagellates, 2 chlorophytes, and a glaucophyte as the outgroup. In the second analysis of a psbA data set, we added 8 peridinin-containing dinoflagellates, 3 stramenopiles, and 1 cryptophyte. In the third data set of rbcL sequences, we used 40 taxa that contained the “red-type Form I” rbcL gene (i.e., excluding the chlorophyte, glaucophyte, and peridinin-containing dinoflagellates, see ref. 22), with the Cyanidiales red algae as the outgroup. Trees were inferred with the minimum evolution (ME) method using LogDet (ME–LgD) distances (23) and the PAUP*4.0b8 (24) computer program. Ten heuristic searches with random-addition-sequence starting trees and tree bisection and reconnection branch rearrangements were done to find the optimal ME tree. To test the stability of monophyletic groups in the ME tree, 2,000 bootstrap replicates were analyzed (25) with the DNA (LogDet distance) and protein (Poisson corrected distances, MEGA V2.0; ref. 26) data sets (ME–Pr). We also conducted Bayesian analysis of the DNA data (MRBAYES V2.0; Ba–D; ref. 27) using a general time reversible (GTR) model and a site-specific γ parameter for each codon site. Bayesian posterior probabilities are roughly equivalent to maximum likelihood bootstrap analysis (28, 29). Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) from a random starting tree was initiated in the Bayesian inference and run for 500,000 generations. A consensus tree was made with the MCMC trees after convergence. For the rbcL data, the GTR + I + Γ model was used in the Bayesian inference using only first + second codon positions (810 nt).

The Shimodaira–Hasegawa (SH) nonparametric bootstrap test was used to compare alternative phylogenetic hypotheses regarding the position of peridinin- and fucoxanthin-containing dinoflagellates (30). The SH test was done by using paup*v4.08b, with rell (resampling estimated log-likelihood) optimization, and 100,000 bootstrap replicates.

Results

PsaA + PsbA Phylogeny.

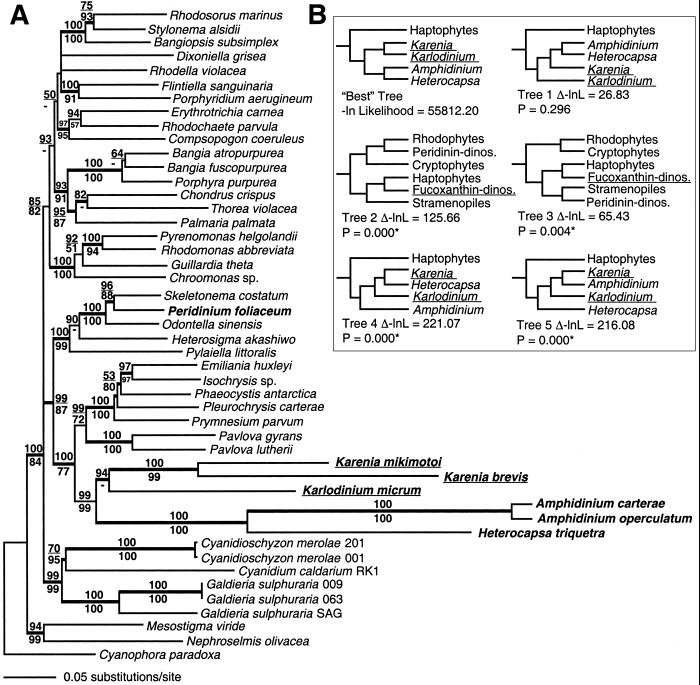

A total 2,352 nucleotides and 784 amino acids from 47 taxa were used in the analysis of the psaA + psbA data set. The ME–LgD tree of the concatenated sequences shows strong support for the monophyly of fucoxanthin- and peridinin-containing dinoflagellates (ME–LgD = 99%, ME–Pr = 99%, Fig. 1A). The dinoflagellates are positioned as sister to the haptophytes with robust bootstrap support and a significant Bayesian posterior probability for this node (ME–LgD = 100%, ME–Pr = 77%, Ba–D = 1.0). Use of only first and second, or only the most highly conserved second codon positions of the psaA + psbA data set in ME–LgD analyses also recovered monophyly of fucoxanthin- and peridinin-containing dinoflagellate plastids (results not shown). In Fig. 1A, P. foliaceum is nested within the Skeletonema and Odontella clade with strong bootstrap and Bayesian support, confirming its origin from a diatom through plastid replacement (17, 18).

Figure 1.

Phylogeny of red algal and red algal-derived plastids by using the combined psaA and psbA sequences. (A) Minimum evolution tree using LogDet distances. The bold letters indicate all dinoflagellates, whereas the underlined taxa contain fucoxanthin. A total of 2,352 nucleotides were considered. The LogDet bootstrap values (2,000 replications) are shown above the branches, and ME protein Poisson bootstrap values are shown below the branches. The thick branches denote >95% posterior probability for groups to the right resulting from a Bayesian inference. A total of 500,000 MCMC generations were run, and the posterior probabilities were determined from 4,368 probable trees. (B) Comparison of the best ME–LgD tree to alternative topologies by using the nonparametric SH bootstrap test. The best tree favored a sister group relationship of peridinin- and fucoxanthin-containing dinoflagellates plastids, however, not significantly (tree 1). The monophyly of dinoflagellate and haptophyte plastid (trees 2 and 3), and the single origin of peridinin-containing dinoflagellate is, however, significantly supported (trees 4 and 5).

We tested alternative hypotheses by using the data set of all three codon positions of psaA + psbA and the SH test (Fig. 1B). In these analyses, the paraphyly of the fucoxanthin-containing dinoflagellates was not rejected (Fig. 1B, tree 1; P = 0.296), whereas the monophyly of peridinin-containing and rhodophyte plastids (the conventional hypothesis; Fig 1B, tree 2; P < 0.000) and stramenopiles plastids (Fig. 1B, tree 3; P = 0.004) was resoundingly rejected. Forcing two independent origins of peridinin in the plastids of Amphidinium and Heterocapsa resulted in a significantly worse tree (Fig. 1B, trees 4 and 5), suggesting that peridinin had a single origin as shown in Fig. 1A.

PsbA Phylogeny.

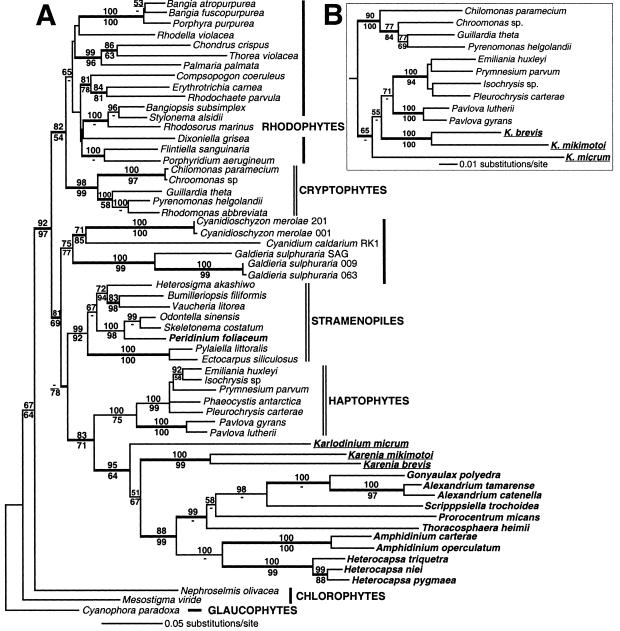

The ME–LgD tree of psbA sequences, which was inferred from a data set of 957 nucleotides and 319 amino acids from 59 taxa, shows a very similar topology to the psaA + psbA phylogeny. The dinoflagellates form a monophyletic clade with haptophytes (Fig. 2A). The dinoflagellates + haptophytes clade is positioned as sister to the stramenopiles, with moderate to strong support in the minimum evolution (ME–Pr = 78%) and Bayesian (P = 1.0) analyses. Within the dinoflagellate clade, the 11 peridinin-containing species are monophyletic with strong support (ME–LgD = 88%, ME–Pr = 99%, Ba–D = 1.0), whereas the fucoxanthin-containing species are paraphyletic at the base of this lineage, consistent with the SH test using the psaA + psbA data (Fig. 1B, tree 1). The peridinin-containing dinoflagellates form two major clades, one that includes Amphidinium + Heterocapsa, and a second that contains the remainder of the species. Again, use of first and second, or only the second codon positions of the psbA data set in ME–LgD analyses showed monophyly of fucoxanthin- and peridinin-containing dinoflagellate plastids (results not shown). As found above, the P. foliaceum psbA sequence grouped with the diatoms (i.e., with Odontella and Skeletonema).

Figure 2.

Phylogeny of red algal and red algal-derived plastids using psbA and rbcL sequences. (A) Minimum evolution psbA tree using LogDet distances. The bold letters indicate all dinoflagellates, whereas the underlined taxa contain fucoxanthin. A total of 957 nucleotides were considered. The LogDet bootstrap values (2,000 replications) are shown above the branches and ME protein Poisson bootstrap values are shown below the branches. The thick branches denote >95% posterior probability for groups to the right resulting from a Bayesian inference. A total of 500,000 MCMC generations were run and the posterior probabilities were determined from 4,141 probable trees. (B) Minimum evolution rbcL tree using LogDet distances. Only the subtree containing the fucoxanthin-containing dinoflagellates (underlined) is shown. The entire tree is shown as Fig. 4. A total of 810 nucleotides (only first and second positions) were considered. The bootstrap and Bayesian inference (4,593 probable trees) were done as above.

RbcL Phylogeny.

The ME–LgD analysis of the first and second codon positions of the “Form I” rbcL gene supports the sister group relationship of fucoxanthin-containing dinoflagellate and haptophyte plastids with a significant Bayesian posterior probability (P = 0.98; Fig. 2B) for this node (see Fig. 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, for the complete tree). The ME–LgD and ME–Pr bootstrap analyses provided, however, only weak support for dinoflagellate–haptophyte monophyly (65% and 31%, respectively). The usage of all three rbcL codon positions in the ME–LgD analysis resulted in a phylogeny that did not support the monophyly of fucoxanthin-containing and haptophyte plastids. The branch lengths within the Karlodinium–Karenia clade were, however, relatively long compared with the haptophyte rbcL sequences when third codons positions were included. This likely explains the “attraction” (31) of the fucoxanthin clade to the outgroup Cyanidiales in this tree (results not shown). In support of this hypothesis, use of γ-corrected distances (ME-GTR + I + Γ) recovered the monophyly of fucoxanthin-containing and haptophyte plastids and Bayesian inference by using the rbcL amino acid sequences and the JTT + Γ model showed a significant posterior probability for the node uniting fucoxanthin-containing and haptophyte plastids (P = 1.0; results not shown). These data provide strong support, therefore, for the monophyly of fucoxanthin-containing and haptophyte plastids. Our results, using an expanded data set of rbcL sequences, is consistent with previous reports (32). The two genera of fucoxanthin-containing dinoflagellates, Karenia and Karlodinium, are paraphyletic at the base of haptophyte clade, a result that is also found in the psbA tree.

Additional Analyses.

We did ME–LgD and Bayesian analyses that included published plastid 16S rRNA data, by using the most highly conserved regions of this gene (678 nucleotides). A multigene tree of the concatenated sequences of 16S rRNA + psaA + psbA (3,030 nucleotides) that included 3 fucoxanthin- and a peridinin-containing dinoflagellate (Heterocapsa triquetra) showed significant support for the sister group relationship of dinoflagellates and haptophytes (ME–LgD = 98%, Ba–D = 0.98; see Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The ME–LgD tree using psaA alone showed a similar topology to the phylogenies inferred from psbA alone (Fig. 2A) and from psaA + psbA (Fig. 1A). There was moderate bootstrap support in the psaA protein analysis (ME–Pr = 78%) and poor support in the minimum evolution analyses (ME–LgD = 54%) for the sister group relationship of dinoflagellates and haptophytes (results not shown).

We also tested for mutational saturation in the data sets used for phylogenetic analyses by correcting for multiple substitutions using the HKY85 model (DNA) and JTT model (protein). Corrected versus uncorrected distances were plotted for the psaA + psbA DNA data set using all three positions, and for the psaA + psbA protein data (Fig. 6A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). This analysis showed minimal mutational saturation, although the DNA data showed slightly more saturation among distantly related taxa than did the protein data. We also analyzed first + second versus third codon positions for these genes (Fig. 6B). The first + second positions have a nearly linear relationship over much of the data set, whereas third positions show considerable saturation for highly divergent taxa suggesting that these data are less useful for resolving deep evolutionary relationships (Fig. 6B).

Discussion

Tertiary Haptophyte Plastid Replacement.

Taken together, our data provide strong evidence for a common origin of peridinin- and fucoxanthin-containing dinoflagellate plastids. The monophyly of dinoflagellate and haptophyte plastid sequences is recovered in all of our phylogenies (except for the rbcL ME–LgD tree using all 3 codon positions; see Results); psaA + psbA (Fig. 1A), psbA (Fig. 2A), and in the 16S rRNA + psaA + psbA analyses (Fig. 5). Other plastid replacements in the dinoflagellates are, however, clearly more recent events in the peridinin-containing taxa, such as the diatom replacement in P. foliaceum (refs. 17 and 18; see Figs. 1A and 2A) and the cryptophyte replacement in Dinophysis acuminata (J.D.H., L. Maranda, H.S.Y., and D.B., unpublished data). Our surprising result in this study contradicts the conventional view that only the fucoxanthin-containing taxa underwent a haptophyte plastid replacement (e.g., refs. 2, 11, and 15) and provides a paradigm for understanding dinoflagellate plastid evolution. Based on our results and the accepted secondary endosymbiotic origin of the haptophyte plastid (e.g., ref. 33), we postulate that the ancestral dinoflagellate acquired its plastid from a haptophyte through a tertiary plastid replacement. The SH test shows the haptophyte origin model to have significantly greater support than any of the alternative hypotheses (Fig. 1B, trees 2 and 3), such as a red algal origin (7), or a stramenopiles origin (34). However, we cannot discriminate between a monophyletic or paraphyletic origin of the fucoxanthin-containing dinoflagellates (Fig. 1B). And, as previously shown, our data also support the monophyly of peridinin-containing dinoflagellates (11, 20).

One realistic concern about our results is that they may be an artifact of the relatively high divergence rate of dinoflagellate plastid genes rather than reflecting the true evolutionary history of the organelles. In this scenario, the dinoflagellate sequences may be “attracted” together because they share long branches rather than because of a monophyletic origin (31). Previous analyses (e.g., refs. 7 and 11) have clearly been hampered by this problem and the trees have often not provided an unambiguous placement of the dinoflagellate plastids (e.g., figure 5 in ref. 11). We have addressed this potentially confounding problem in the following ways. First, we have increased the taxon sampling for both red algae and their derived plastids to include all potential sister groups for the dinoflagellate genes and to break long branches that may cause homoplasious attraction. Second, we have used robust phylogenetic methods to ameliorate the effects of high divergence rates (i.e., γ-corrected distances, Bayesian inference, use of protein sequences, use of only first and second or only the most highly conserved second codon positions) and a biased nucleotide content (LogDet transformation). Third, we have increased the phylogenetic signal by augmenting the length of the sequences being compared through multigene sampling. The fact that each gene, singly or in combination, supports the monophyly of fucoxanthin- and peridinin-containing dinoflagellate plastids suggests to us that this result is robust and not the outcome of an uniform bias in all of these genes.

The best way to correct for long-branch attraction is to sample slowly evolving genes (35), but this may be an improbable solution for dinoflagellates because all plastid genes that have been studied until now have elevated divergence rates (e.g., refs. 7, 11, and 20). However, our analyses of pairwise sequence distances indicate that the psaA and psbA coding regions do not show extensive mutational saturation and that even the third positions of these sequences encode phylogenetic signal (see Fig. 6). Use of nuclear-encoded photosynthetic genes would be another possible solution, but we predict that many of these genes would support a red algal ancestry of the dinoflagellate plastid because they trace their origin to the initial secondary endosymbiosis (36). Some plastid-targeted genes of haptophyte origin are also predicted to exist in the dinoflagellate nuclear genome as a result of gene transfer following the tertiary endosymbiosis. Analysis of plastid genes is, therefore, of fundamental importance to understanding plastid evolution in the dinoflagellates.

Given that our hypothesis of the monophyly of fucoxanthin- and peridinin-containing dinoflagellate plastids is correct, then we envision two possible scenarios for their relative order of divergence: (i) after the tertiary haptophytic-plastid replacement, the fucoxanthin- and peridinin-containing dinoflagellates diverged as sister groups (Fig. 1A), or (ii) the peridinin-containing dinoflagellates emerged from within a clade of fucoxanthin-containing ancestors (Fig. 2A). In either case, we hypothesize that the fucoxanthin-containing plastid (13) should be regarded as the primitive condition (i.e., fucoxanthin is present in the plastid donor) with the presence of peridinin being a derived state. This idea is reinforced by the observation that peridinin-containing dinoflagllate plastids also share a suite of unique characters not found in fucoxanthin plastids (e.g., “Form II” rbcL gene, single-gene circles; see below), which strongly supports a single origin and monophyly of these taxa. However, our data do not allow us to determine the timing of the haptophyte replacement. It may have occurred at the base of the dinoflagellates or this tertiary plastid may have a much longer evolutionary history.

A fully resolved host tree of the dinoflagellates is critical to test our hypothesis of a basal haptophyte replacement. Presumably, the topology of this tree should mirror that of the plastid trees given a single organelle origin. Existing analyses using nuclear small subunit rRNA show the fucoxanthin-containing species as an early diverging group, but with no bootstrap support for their monophyly or for their relationship to peridinin-containing taxa (10). Trees inferred with large subunit rRNA support monophyly of fucoxanthin-containing species but with poor support for their position relative to other dinoflagellates (12, 37).

Evolution of Dinoflagellate Plastids.

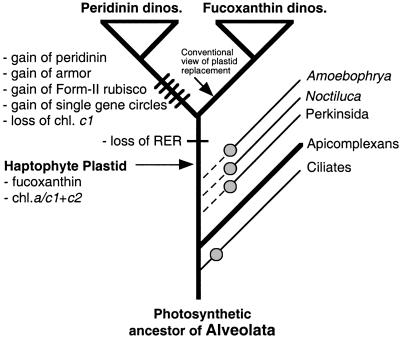

A model of dinoflagellate plastid evolution is presented in Fig. 3. This scheme presumes that the common ancestor of the alveolates contained a plastid of red algal origin (irrespective of whether it was a secondary or a tertiary endosymbiont; refs. 10, 34, and 36). This plastid was apparently lost in the ciliates, whereas in the Apicomplexa, which are intracellular parasites, it was reduced to a nonphotosynthetic organelle of unknown function (38). The branching of several nonphotosynthetic lineages before the divergence of the photosynthetic dinoflagellates suggests that multiple plastid losses may have occurred (i.e., Perkinsida, Noctiluca, and Ameobophrya; ref. 10) in the evolution of the alveolates. Some time after the haptophyte replacement of the plastid, the dinoflagellates diverged into two groups. One group retained the ancestral haptophyte characteristics in its plastid (fucoxanthin, chlorophyll c1 + c2), whereas the second group underwent several major changes including the evolution of peridinin (replacing fucoxanthin), loss of chlorophyll c1, the remarkable reduction of its plastid genome to single gene circles (7, 39), the development of cellulose armor, and the origin of a divergent nuclear encoded “Form II” rbcL gene (40, 41). It is possible that peridinin could have evolved from a modification of the ancestral fucoxanthin biosynthesis pathway because these are structurally related xanthophylls (for details, see refs. 13 and 42). Because haptophytes contain a 4-membrane bound plastid, we postulate that the outer rough endoplasmic reticulum membrane of this organelle was lost after the tertiary endosymbiosis resulting in the 3 smooth membranes that surround both fucoxanthin- and peridinin-containing dinoflagellate plastids (14).

Figure 3.

Putative model of plastid evolution mapped on a current “host” tree of the Alveolata (adapted from Saldarriaga et al.; ref. 10). Plastid-containing lineages are shown with the thick branches and plastid loss is denoted with a filled circle. The ancestral alveolate plastid is presumed to have been lost multiple independent times in the aplastidial taxa (i.e., Perkinsida, Noctiluca, and Amoebophrya). The broken lines denote uncertainty about the evolutionary interrelationships of the aplastidial taxa. The hatchmarks indicate the origin of novel characters in the peridinin-containing plastids. The haptophyte plastid replacement is believed to have occurred at least before the split of the fucoxanthin- and peridinin-containing dinoflagellates. The conventional view of the haptophyte plastid replacement occurring on the branch uniting fucoxanthin-containing plastids is shown.

In summary, our results provide important insights into the complex evolutionary history of dinoflagellates. Previous analysis of nuclear-encoded cytosolic genes have suggested a sister group relationship to the stramenopiles, indicating the host affinity for this group (43, 44). Nuclear-encoded, photosynthetic genes suggest an origin of the plastid from a red alga (34, 36). These genes have presumably been inherited vertically from the common ancestor of stramenopiles and dinoflagellates (i.e., the shared red algal secondary endosymbiont, refs. 34 and 36; Fig. 3). Plastid-encoded genes of both peridinin- and fucoxanthin-containing dinoflagellates show a strong relationship to the haptophytes, indicating that a tertiary plastid replacement occurred before the split of these lineages. As stated above, our model predicts the presence of plastid-targeted, nuclear-encoded genes (and possibly cytosolic genes) of both red algal and haptophyte origin in the dinoflagellate nucleus. A genome-wide approach will most likely be necessary to understand fully the relative contributions of these successive endosymbioses to dinoflagellate evolution. Most remarkably, some of the peridinin-containing taxa have gone on to replace their plastid yet again [e.g., P. foliaceum (17, 18) and Dinophysis (16)]. The genomic contribution of these additional rounds of endosymbiosis to dinoflagellate evolution also remains to be determined.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. W. Freshwater and E. H. Bae for providing dried thallus of Palmaria and Chondrus. H.S.Y. was supported by the Post Doctoral Fellowship Program of the Korean Science and Engineering Foundation. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grants DEB 01-07754 and MCB 01-10252 (to D.B.).

Abbreviations

- psaA

photosystem I P700 chlorophyll a apoprotein A1

- psbA

photosystem II reaction center protein D1

- rbcL

ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase

- ME

minimum evolution

- LgD

LogDet

- MCMC

Markov chain Monte Carlo

- SH

Shimodaira–Hasegawa

Footnotes

References

- 1.Taylor F J R. In: Handbook of Protoctista: The Structure, Cultivation, Habitats and Life Histories of the Eukayotic Microorganisms and their Descendants Exclusive of Animals, Plants and Fungi. Margulis L, Corliss J O, Melkonian M, Chapman D J, editors. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 1990. pp. 419–437. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schnept E, Elbrächter M. Grana. 1999;38:81–97. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pawlowski J, Holzmann M, Fahrni J F, Pochon X, Lee J J. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2001;48:368–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2001.tb00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham L D, Wilcox L W. Algae. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice–Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dodge J D. In: The Chromophyte Algae: Problems and Perspective. Green J C, Leadbeater B S C, Diver W L, editors. Vol. 38. Oxford: Clarendon; 1989. pp. 207–227. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeffrey S W. In: The Chromophyte Algae: Problems and Perspective. Green J C, Leadbeater B S C, Diver W L, editors. Vol. 38. Oxford: Clarendon; 1989. pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Z, Green B R, Cavalier-Smith T. Nature (London) 1999;400:155–159. doi: 10.1038/22099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavalier-Smith T. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:174–182. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01598-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer J D, Delwiche C F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7432–7435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saldarriaga J F, Taylor F J, Keeling P J, Cavalier-Smith T. J Mol Evol. 2001;53:204–213. doi: 10.1007/s002390010210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Z, Green B R, Cavalier-Smith T. J Mol Evol. 2000;51:26–40. doi: 10.1007/s002390010064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daugbjerg N, Hansen G, Larsen J, Moestrup Ø. Phycologia. 2000;39:302–317. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bjørnland T, Liaaen-Jensen S. In: The Chromophyte Algae: Problems and Perspective. Green J C, Leadbeater B S C, Diver W L, editors. Vol. 38. Oxford: Clarendon; 1989. pp. 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen G, Moestrup Ø, Roberts K R. Phycologia. 2000;39:365–376. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tengs T, Dahlberg O J, Shalchian-Tabrizi K, Klaveness D, Rudi K, Delwiche C F, Jakobsen K S. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:718–729. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnepf E, Elbrächter M. Botanica Acta. 1988;101:196–203. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chesnick J M, Morden C W, Schmieg A M. J Phycol. 1996;32:850–857. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chesnick J M, Kooistra W H, Wellbrock U, Medlin L K. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1997;44:314–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1997.tb05672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe M M, Suda S, Inouye I, Sawaguchi T, Chihara M. J Phycol. 1990;26:741–751. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takishita K, Nakano K, Uchida A. Phycol Res. 1999;47:257–262. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilbert D G. SEQPUP: A Biological Sequence Editor and Analysis Program for Macintosh Computer. Bloomington: Indiana Univ.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delwiche C F, Palmer J D. Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13:873–882. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lockhart P J, Steel M A, Hendy H D, Penny D. Mol Biol Evol. 1994;11:605–612. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swofford D L. PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods) Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 2002. , Version 4.0b8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felsenstein J. Evolution (Lawrence, Kans) 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar S, Tamura K, Jakobsen I B, Nei M. MEGA2: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Software. Tempe: Arizona State Univ.; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huelsenbeck J P, Ronquist F. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huelsenbeck J P, Ronquist F, Nielsen R, Bollback J P. Science. 2001;294:2310–2314. doi: 10.1126/science.1065889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larget B, Simon D L. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:750.759. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimodaira H, Hasegawa M. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:1114–1116. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felsenstein J. Syst Zool. 1978;27:401–410. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takishita K, Nakano K, Uchida A. Phycol Res. 2000;48:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Müller K M, Oliveira M C, Sheath R G, Bhattacharya D. Am J Bot. 2001;88:1390–1400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Durnford D G, Deane J A, Tan S, McFadden G I, Gantt E, Green B R. J Mol Evol. 1999;48:59–68. doi: 10.1007/pl00006445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Philippe H. Protist. 2000;151:307–316. doi: 10.1078/S1434-4610(04)70029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fast N M, Kissinger J C, Roos D S, Keeling P J. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:418–426. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hansen G, Daugbjerg N, Henriksen P. J Phycol. 2000;36:394–410. [Google Scholar]

- 38.McFadden G I, Waller R F. BioEssays. 1997;19:1033–1040. doi: 10.1002/bies.950191114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barbrook A C, Howe C J. Mol Gen Genet. 2000;263:152–158. doi: 10.1007/s004380050042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morse D, Salois P, Markovic P, Hastings J W. Science. 1995;268:1622–1624. doi: 10.1126/science.7777861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmer J D. BioEssays. 1995;17:1005–1008. doi: 10.1002/bies.950171202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lohr M, Wilhelm C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8784–8789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van de Peer Y, De Wachter R. J Mol Evol. 1997;45:619–630. doi: 10.1007/pl00006266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van de Peer Y, Baldauf S L, Doolittle W F, Meyer A. J Mol Evol. 2000;51:565–576. doi: 10.1007/s002390010120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.