During DNA replication and transcription, the winding of the DNA helix undergoes dramatic changes that give rise to DNA supercoiling. Additionally, both DNA replication and recombination can leave the DNA in a tangled, catenated, or interwound state. DNA topoisomerases are the enzymes charged with resolving these topological problems in the DNA (for reviews, see refs. 1–3). In addition, in bacteria two or more DNA topoisomerases act in concert to maintain a fixed global level of helical tension in the DNA that is critical for its proper function.

Topoisomerases alter the topological state of the DNA by either passing one strand of the helix through the other strand (type I family) or by passing a region of duplex DNA through another region of duplex DNA (type II family). The two families of enzymes carry out this molecular sleight of hand by reversibly cleaving one or both strands of the DNA, respectively. The reversibility of the reaction is ensured by the covalent attachment of the enzyme to a DNA end (or ends) through a phosphodiester linkage involving a tyrosine residue in the enzyme. The type I family is further subdivided into two subfamilies depending on the polarity of attachment of the topoisomerase to the DNA; members of the type IA subfamily become attached to 5′ phosphate termini, whereas members of the type IB subfamily attach to 3′ phosphates. The requirement for a type IA enzyme to bind a short single-stranded region in the substrate further distinguishes the type IA enzymes from the type IB enzymes, which prefer completely duplex DNA. What happens after cleavage to effect the strand passage reaction has long fascinated investigators working on the type I enzymes. The experiments described by Dekker et al. (4) in this issue of PNAS provide an elegant and convincing test of a model for the strand passage reaction by the type IA enzymes.

After a type I enzyme has nicked the DNA, there are two alternative hypotheses to account for the strand passage reaction. In one model, strand passage is accomplished by simple rotation of the helix on the side of the single-strand break that is not fixed by covalent attachment to the enzyme. Indeed, the crystal structure of human topoisomerase I, a type IB enzyme, is most consistent with such a DNA rotational model (5). Notably, this model does not limit the number of rotations per cleavage-religation cycle and for the vaccinia topoisomerase, another type IB enzyme, the DNA rotates an average of five times before reclosure occurs (6). The alternative model for the strand passage reaction posits that the enzyme not only is covalently attached to one end of the broken strand, but is also noncovalently bound to the other end to create a bridge through which the intact strand is passed. This enzyme-bridging mechanism for a type I enzyme would also provide for the catenation or decatenation of two circular molecules in which a region of DNA from one circle is passed through an enzyme-generated break in a single-stranded gap of the other circle. Early evidence indicating that the prototype of the type IA enzymes, Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I, interacts with both ends of a region of single-stranded DNA at the site of a nick (7), suggested an enzyme-bridging mechanism for this subfamily of topoisomerases. The publication of the crystal structure of a 67-kDa N-terminal fragment of E. coli topoisomerase I provided strong support for the enzyme-bridging strand-passage mechanism (8).

Determining the actual step size for supercoil relaxation by a type IA topoisomerase is not easily accomplished with traditional biochemical approaches.

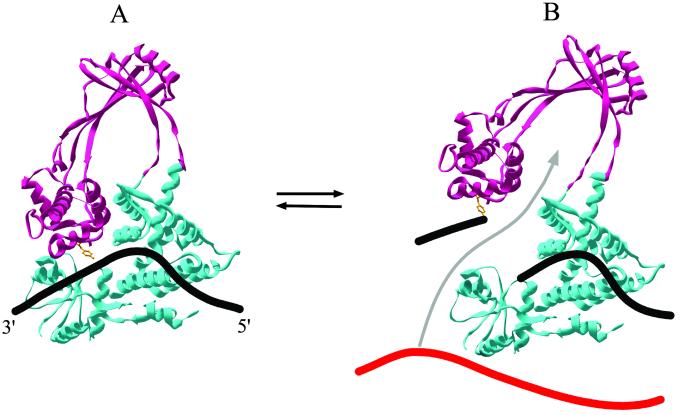

As can be seen in Fig. 1A, E. coli topoisomerase I is shaped like a torus with an internal hole large enough to accommodate double-stranded DNA. A recent co-crystal structure of E. coli topoisomerase III, a type IA relative of E. coli topoisomerase I (9), confirms the earlier conjecture (8) that the single-stranded DNA substrate is bound along the bottom of the structure and extends across the tip of a flexible arm containing the active-site tyrosine (Fig. 1A). As diagrammed in Fig. 1B, this configuration is ideally suited for the creation of an enzyme-bridged gap in the cleaved or scissile strand through which a second strand of DNA can be passed. When the two ends of the broken strand are reconnected, the passed strand remains within the hole of the torus. Thus, before the enzyme can undergo another cycle of cleavage, strand passage, and religation, the enzyme must open a second time to release the passed strand (2). The need to reset the enzyme after each strand passage step dictates that only one supercoil can be relaxed per cycle. Although the crystal structure provided excellent support for the enzyme-bridging model for the type IA enzymes, the critical prediction of the model that relaxation must occur in steps of one has remained untested until now (4).

Fig 1.

Enzyme-bridged DNA strand-passage model for type IA topoisomerases. The ribbon diagrams are based on the crystal structure of E. coli DNA topoisomerase I (PDB ID code ) and show the closed form of the enzyme before cleavage of the DNA (single strand of DNA modeled as a thick black line; A) and the open form after cleavage with both ends of the broken DNA strand associated with the enzyme (B). The active site tyrosine that becomes covalently attached to the 5′ end of the broken strand is shown in ball and stick and colored orange. The top region of the protein [domains II and III (8)] that is hypothesized to move upwards after cleavage is colored magenta; the bottom region (domains I and IV) is colored cyan. In B, strand passage moves a single strand of DNA from either the same or a different DNA molecule (shown in red) through the enzyme-bridged opening in the cleaved strand (movement depicted by gray arrow). The original ribbon diagram in A was generated using SWISS-PDB VIEWER V.3.51 software (Glaxo Wellcome Experimental Research). Subsequent manipulations including the overlay of the DNA are approximate and were performed with PHOTOSHOP (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

The task of determining the actual step size for supercoil relaxation by a type IA topoisomerase is a daunting one not easily accomplished with traditional biochemical approaches or by the analysis of populations of molecules in solution. Such a test demands an ability to analyze the kinetics of DNA relaxation when only a single molecule of enzyme is bound to the substrate, assay conditions in which the rate of relaxation is approachable experimentally, and sufficient sensitivity to detect the removal of a single supercoil. These requirements were elegantly satisfied by the single molecule approach used by Dekker et al. (4). In the basic setup, a linear ≈10-kb DNA molecule is attached at one end to a glass surface and at the other end to a magnetic bead. The properties of the DNA are altered by using a magnet to apply a defined stretching force on the DNA and by rotation of the magnet to introduce supercoils of either sign into the DNA. The introduction of either negative or positive supercoils results in a shortening of the DNA that is detected microscopically by a vertical movement of the bead. The rate of supercoil relaxation by a topoisomerase is then simply measured by the reverse movement of the bead as the extension of the DNA is increased. This basic approach had been used previously by the same group to show that type II topoisomerases alter supercoiling in steps of two (10), but similar experiments for the type I enzymes have proven more challenging.

A series of innovations rendered the type IA topoisomerase reaction accessible to this kind of single-molecule analysis. First, the linear DNA was constructed with a central 12-base mismatch that provided the required single-stranded region for enzyme binding yet was short enough to ensure that only one molecule of enzyme would be bound. Second, the authors made use of a previous observation that the type IA topoisomerases can relax positively supercoiled DNA provided the molecule contains a single-stranded bubble like the one engineered into their substrate (7). Finally, the application of a defined stretching force on the positively supercoiled DNA was found to slow down the rate of relaxation by the enzyme. This effect in combination with the use of a suboptimal Mg2+ concentration brought the relaxation rate into the measurable time scale. Despite considerable scatter in the raw data, the results could be averaged and fit to a series of steps, most of which corresponded to the DNA extension predicted for the relaxation of a single positive supercoil. Although a few steps had an amplitude consistent with the removal of two supercoils, these steps could be explained as two cycles of cleavage and religation that occurred too close together in time to be resolved by the analysis. Consequently these exceptional steps of two do not disprove the enzyme-bridging strand-passage hypothesis.

To dispel any concerns about the use of relatively high stretching forces and low Mg2+ to slow the reaction, the authors applied a second independent type of analysis based on the nature of the fluctuations in DNA extension to also estimate the step size of the reaction. Using lower stretching forces and near physiological Mg2+ concentrations, the step size for supercoil relaxation was confirmed to be one. Similar results were also obtained for the distantly related type IA topoisomerase from the hyperthermophile, Thermotoga maritima. Overall, these results provide compelling evidence that type IA topoisomerases strictly relax supercoils one at a time and therefore fulfill a key prediction of the enzyme-bridging model for DNA relaxation.

Three additional observations made by Dekker et al. (4) warrant mention. First, they confirmed that E. coli topoisomerase I will not relax positive supercoils in completely duplex DNA and second, that relaxation of negative supercoils is promoted by moderate increases in the force on the molecule that favor the formation of unpaired regions in the DNA to which the enzyme can bind (11). Third, they discovered that although an increase in the force promoted strand separation in negatively supercoiled DNA and therefore enzyme binding, exceeding a threshold level of force rendered the topoisomerase inactive. As mentioned previously, this same inhibitory effect of high force was observed for the relaxation of positive supercoils in the substrate with the 12-base mismatch, but was not observed with a DNA containing a 25-base bulge. The different behavior for these two substrates suggests the interesting possibility that when the DNA is sufficiently taut, the two strands in the unpaired or mismatched region of the DNA are held so close together that binding of the enzyme and/or strand passage is impeded.

The finding that the type IA topoisomerases function by an enzyme-bridging mechanism has important implications for the biological function of this group of enzymes. Members of the type IA subfamily can be further divided into two classes based on their biochemical properties (2). The first class of IA enzymes, as exemplified by E. coli topoisomerase I, is capable of relaxing negative supercoils in a typical plasmid DNA, but complete relaxation does not occur because of the requirement for a minimum level of negative supercoiling during enzyme binding to facilitate unpairing of a region of duplex. This feature of the reaction is consistent with the essential role of the enzyme in the cell to prevent excessive negative supercoiling by the DNA gyrase (1). Although this role as a governor on DNA gyrase has been extensively characterized only in E. coli, it is likely that a type IA topoisomerase is similarly required in all eubacteria and archaebacteria containing a DNA gyrase. A type I topoisomerase with an enzyme-bridging mechanism is better suited for this cellular role than one with a rotational mechanism because it affords the cell a finer level of control over global DNA topology. For instance, removal of negative supercoils one step at a time allows an assessment of cellular DNA supercoiling after each cleavage–religation cycle, and when the lower limit of negative supercoiling is reached the enzyme simply dissociates to cease relaxing the DNA. With a rotational mechanism, there is no obvious way to prevent the enzyme from excessive relaxation in a given cycle, which could drive the negative supercoiling to suboptimal levels.

Members of the second class of type IA enzymes, found in many bacteria, are functionally distinct from topoisomerases I and are referred to as DNA topoisomerases III (2, 3). Unlike topoisomerases I, topoisomerases III require that the DNA be hypernegatively supercoiled to be a substrate for relaxation, suggesting that topoisomerases III have a lower affinity for single strands and are therefore less able to facilitate the opening of the helix on binding. On the other hand, topoisomerases III are much more efficient than topoisomerases I at carrying out the catenation and decatenation of gapped DNA circles. These properties of the bacterial enzymes are shared by the topoisomerases III found in eukaryotes, consistent with the view that this second class of type IA enzymes provides a distinct function in all cell types. Furthermore, topoisomerases III appear to be functionally associated with helicases in both bacteria and eukaryotes. Taken together, these properties suggest that topoisomerases III are likely involved in disentangling partially single-stranded intermediates formed during replication, repair, or recombination (3, 4). Given this role, one imagines that the enzyme first cleaves a single strand of DNA and promotes the passage of either another single strand or a region of duplex DNA through the break. If this scenario is correct, then it would be absolutely essential for the enzyme to maintain an association with both ends of the cleaved strand, otherwise recapture of the free end necessary for reclosure would likely be problematic. Clearly an enzyme-bridging strand-passage mechanism is uniquely suited to carry out this type of reaction.

In summary, this work provides convincing biochemical evidence in favor of the enzyme-bridging relaxation mechanism for type IA topoisomerases. Furthermore, this mechanism fits well with current ideas concerning the role of these enzymes in the cell. Finally, the results very nicely illustrate the unique power of single-molecule biochemistry and raise the possibility that a similar approach might be used to verify the proposed rotational model for the type IB subfamily of topoisomerases (5).

Acknowledgments

I thank Sharon Schultz and Heidrun Interthal for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM60330.

See companion article on page 12126.

References

- 1.Wang J. C. (1996) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65, 635-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Champoux J. J. (2001) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 369-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J. C. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3, 430-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dekker N. H., Rybenkov, V. V., Duguet, M., Crisona, N. J., Cozzarelli, N. R., Bensimon, D. & Croquette, V. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12126-12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart L., Redinbo, M. R., Qiu, X., Hol, W. G. & Champoux, J. J. (1998) Science 279, 1534-1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stivers J. T., Harris, T. K. & Mildvan, A. S. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 5212-5222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirkegaard K. & Wang, J. C. (1985) J. Mol. Biol. 185, 625-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lima C. D., Wang, J. C. & Mondragon, A. (1994) Nature (London) 367, 138-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Changela A., DiGate, R. J. & Mondragon, A. (2001) Nature (London) 411, 1077-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strick T. R., Croquette, V. & Bensimon, D. (2000) Nature (London) 404, 901-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strick T. R., Croquette, V. & Bensimon, D. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10579-10583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]