Abstract

EmrE is a small multidrug transporter that extrudes various drugs in exchange with protons, thereby rendering Escherichia coli cells resistant to these compounds. In this study, relative helix packing in the EmrE oligomer solubilized in detergent was probed by intermonomer crosslinking analysis. Unique cysteine replacements in transmembrane domains were shown to react with organic mercurials but not with sulfhydryl reagents, such as maleimides and methanethiosulfonates. A new protocol was developed based on the use of HgCl2, a compound known to react rapidly and selectively with sulfhydryl groups. The reaction can bridge vicinal pairs of cysteines and form an intermolecular mercury-linked dimer. To circumvent problems inherent to mercury chemistry, a second crosslinker, hexamethylene diisocyanate, was used. After the HgCl2 treatment, excess reagent was removed and the oligomers were dissociated with a strong denaturant. Only those previously crosslinked reacted with hexamethylene diisocyanate. Thus, vicinal cysteine-substituted residues in the EmrE oligomer were identified. It was shown that transmembrane domain (TM)-1 and TM4 in one subunit are in contact with the corresponding TM1 and TM4, respectively, in the other subunit. In addition, TM1 is also in close proximity to TM4 of the neighboring subunit, suggesting possible arrangements in the binding and translocation domain of the EmrE oligomer. This method should be useful for other proteins with cysteine residues in a low-dielectric environment.

Keywords: ion-coupled transporter, o-PDM, mercurials, drug resistance, helix packing

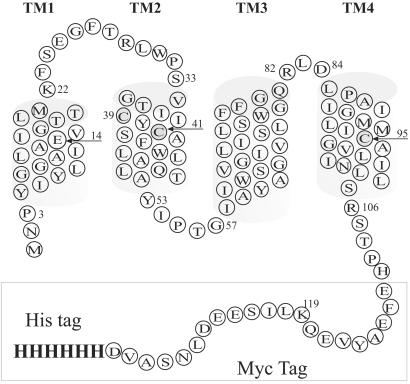

EmrE, a protein from Escherichia coli, provides a unique model for the study of multidrug transporters (1–3). It is a small transporter, 110 aa in length (Fig. 1), that extrudes various drugs in exchange for protons, thereby rendering bacteria resistant to these drugs (2, 3). The protein has been characterized, purified, and reconstituted in a functional form (4). EmrE has only one membrane-embedded charged residue, Glu-14, which is conserved in more than 60 homologous proteins (5). Glu-14 was shown to be part of a binding site for both protons and substrates (6, 7). The oligomeric structure seen in two-dimensional crystals of EmrE is a dimer (8). Substrate binding to purified EmrE and negative dominance experiments support the contention that the functional unit of the protein is a dimer of dimers (1, 9, 10).

Fig 1.

Secondary structure model of EmrE-His. The residues in the square are the Myc-His tag.

Extensive use of cysteine-specific reagents has been made in many crosslinking experiments in membrane proteins (see, for example, refs. 11–14). The reagents commonly used react more rapidly with thiolates than with thiols. Therefore, their use is limited to hydrophilic loops or to areas of the protein that are accessible to solvent. The method described here supplies a tool to explore domains with low dielectric constants. It should be suitable to any protein that can be visualized, for example, by radiolabeling or by immunological techniques.

In this study, relative helix packing in the EmrE oligomer was probed by intermonomer homo- and heterocrosslinking analysis. The majority of the unique cysteine replacements in transmembrane domains do not react with sulfhydryl reagents, such as maleimides and methanethiosulfonates (15), but some of them react with organic mercurial reagents (16). Mercury II salts are known to react rapidly and selectively with sulfhydryl groups, bridging the vicinal pairs of cysteines and forming an intermolecular mercury-linked dimer (17). The equilibrium between crosslinked and singly substituted species (S-HgCl) prevented the direct use of this reagent. Therefore, a protocol was developed to circumvent this limitation. The effectiveness of the technique was demonstrated by an extensive study of transmembrane domain (TM)-4 where six membrane-embedded mutants located in the same face of the helix were shown to crosslink with TM4 of a neighboring subunit as a result of the reaction with HgCl2. Residues exposed to the solvent reacted also with o-PDM (o-phenylene dimaleimide), a dimaleimide crosslinker. The results validate the technique and suggest the proximity of TM1 and TM4 in each one of the monomers of EmrE.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial Strains and Plasmids.

E. coli JM109 (18) and TA15 strains (19) were used throughout this work. The plasmids used are pT7–7 (20) derivatives with (EmrE-His, Fig. 1; ref. 1) or without (4) a six-histidine tag. A cysteine-less EmrE-His protein was constructed with serine [CL-EmrE-His (EmrE-His in which the three native cysteine residues were replaced with serine)] or alanine replacements [CLA-EmrE-His (EmrE-His in which the three native cysteine residues were replaced with alanine)].

Mutagenesis.

The construction and characterization of the following mutants† were previously described: I11C, L12C, A13C, V15C, I16C, G17C, T18C, G57C, L83C, I94C, A96C, G97C, and H110C, all in CL background, in ref. 15; CL-C95 in ref. 16; and E14C, K22C, and K22R in wild-type background in refs. 9 and 21. To construct existing mutants in other backgrounds, the corresponding template was used (CL, CLA, CL-EmrE-His, or CLA-EmrE-His as indicated for each experiment).

For new mutations, sets of two overlapping oligonucleotide primers containing the desired mutation were used in PCR mutagenesis as described by Ho et al. (22). The outside primers were those used for the wild-type EmrE (4). The template was CLA-EmrE-His.

Mutations that were previously generated in plasmids other than pT7–7, or were not tagged, were transferred as follows: The DNA was amplified using the outside primers described (4). The product was digested with NdeI and EcoRI and ligated to pT7–7 derivative with EmrE-His previously digested with the same enzymes. The primer containing the EcoRI site eliminates the stop signal and introduces a new site that was previously engineered in EmrE-His for this purpose.

All of the PCR-amplified products were sequenced to ensure that no other mutations occurred during the amplification process.

The activity of the mutants in the various backgrounds was characterized as previously described in the corresponding publications, namely for their ability to confer resistance to toxic compounds, for protein expression, tetraphenylphosphonium (TPP+) binding, and methyl-viologen transport. In summary, all of the mutants display TPP+ binding activity under the conditions used for crosslinking except for three: L7C, E14C, and T18C. I11C displays a lower affinity to TPP+ and A10C has modified pH dependence (N. Gutman and S.S., unpublished results). Resistance to toxic compounds was tested on solid media as described (15). Overexpression and specific labeling of EmrE was performed as described (15).

HgCl2 Crosslinking.

Membranes (≈78,000 dpm per 10 μg of total protein) prepared from cells expressing EmrE mutants selectively labeled with [35S]methionine were solubilized in 0.8% DDM-Na buffer [150 mM NaCl/15 mM Tris⋅Cl (pH 7.5), containing 0.8% n-dodecyl-β-maltoside (DDM); final volume 60 μl]. In parallel, denatured protein was prepared for negative controls by solubilization in SDS-urea buffer [2% SDS/6 M urea/15 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5) buffer].

HgCl2 was added to a final concentration of 50 μM. After 5 min at room temperature, excess reagent was removed by gel filtration on a G25-Sephadex column previously equilibrated in 0.08% DDM-Na buffer. For the negative controls mentioned above, equilibration was done with SDS-urea buffer.

The eluted samples (150 μl) were mixed with 600 μl of SDS-urea buffer. After 15 min at 25°C, hexamethylene diisocyanate (HMDC; dispersed in 0.8% DDM) was added to a final concentration of 0.2% (vol/vol). After 1 h at 25°C the reaction was stopped by addition of 75 μl of a mixture containing 15% 2-mercaptoethanol, 150 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 6.1), 0.2% bromophenol blue, and 52.5% glycerol. The samples were incubated for at least 5 min at room temperature to complete scavenging of the reagents by 2-mercaptoethanol. Positive controls for HMDC crosslinking (without HgCl2) were obtained by mixing the eluents with HMDC before the addition of SDS-urea buffer. The degree of crosslinking was assessed by separation of the samples in 16% Tricine gels (23) and analysis of the radioactive bands by using a Fujifilm FLA-3000 Phosphoimager.

Crosslinking with o-PDM.

Membranes prepared from cells expressing EmrE mutants selectively labeled with [35S]methionine were solubilized as described above, and o-PDM was added to a final concentration of 100 μM. The reaction was stopped after 1 h at room temperature by addition of sample buffer: 2% 2-mercaptoethanol/0.125 M Tris⋅HCl (pH 6.8)/4% SDS/20% glycerol/0.2% bromophenol blue. Samples containing ≈5,500 dpm of labeled [35S]EmrE were analyzed on 16% Tricine gels.

o-PDM Crosslinking Between Different Unique Cysteine Replacements.

Hetero-oligomers were prepared by mixing tagged and untagged proteins as described (10). Membranes (≈78,000 dpm per 10 μg of total protein) prepared from cells expressing EmrE mutants selectively labeled with [35S]methionine were solubilized in 0.8% DDM-Na buffer (final volume 50 μl). Untagged protein was prepared by digestion of 40 μl of the above suspension with 30 μl of Trypsin agarose beads slurry [Immobilized TPCK-Trypsin, Pierce; 200 p-tosyl-l-arginine methyl ester (TAME) units/ml gel]. The slurry was prepared by suspending 50-μl beads in 1 ml of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8) and 0.08% DDM. After 1 h incubation at 37°C the beads were removed by pulse centrifugation. To generate the hetero-oligomers, equivalent amounts of [35S]methionine-labeled tagged and untagged proteins were mixed and incubated for 15 min at 80°C. The supernatants were collected after centrifugation for 5 min at 20,800 × g at 4°C and subjected to o-PDM crosslinking as described above.

Results

HgCl2 as a Crosslinker of Membrane-Embedded Residues.

The majority of the EmrE residues in transmembrane domains are inaccessible to water soluble sulfhydryl reagents, such as maleimides and methanethiosulfonates. On the other hand, organic mercurial reagents were shown to react with the membrane-embedded cysteines in wild-type EmrE (16). Mercury II salts are known to react rapidly and selectively with sulfhydryl groups, bridging the vicinal pairs of cysteines and forming an intermolecular mercury-linked dimer (17).

Inhibition studies (not shown) showed that HgCl2 (100 μM) completely abolished TPP+ binding activity of wild-type EmrE, a protein with three cysteine residues at positions 39, 41, and 95. At the same concentration of HgCl2, activity of a CL-EmrE-His protein is hardly inhibited (<10%), confirming the specificity of the effect. Each of the individual native cysteine residues put back in CL-EmrE-His was inhibited to varying degrees, C95 being the most sensitive (80% inhibition), and C39 the least (25%). Therefore, HgCl2 reacted with at least some of the membrane-embedded residues of EmrE and was a potential crosslinker.

The equilibrium between crosslinked and singly substituted species (S-HgCl) formed by the reaction of protein with HgCl2 presents a problem for the use of this reagent. In experiments not shown, we demonstrated that crosslinking was detected in SDS/PAGE even in proteins treated with HgCl2 after denaturation with SDS-urea (i.e., under conditions in which mercury reacted with single cysteine residues). We concluded that, in these cases, crosslinking occurred during concentration in the stacking gel or thereafter. We, therefore, could not use this reagent for direct assay of crosslinking.

A Two-Step Protocol for Analysis of Crosslinking in Reducing SDS/PAGE.

An alternative protocol was designed so that the separation on SDS/PAGE was performed after quenching the reactive species in the sample with 2-mercaptoethanol. This was feasible because of an additional irreversible crosslinking step in which HMDC, an amine-reacting crosslinker, was used.

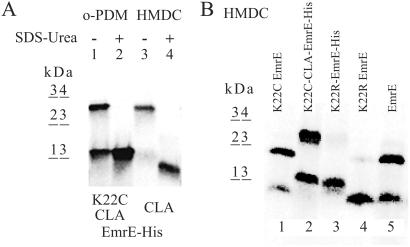

Native EmrE oligomers in DDM (Fig. 2A, lane 3), but not denatured ones in SDS-urea (lane 4), are crosslinked with HMDC. HMDC reacts generally with lysine and N-terminal amino groups and also, potentially, with cysteine sulfhydryls. EmrE contains only a single lysine at position 22. A second lysine was introduced in the Myc epitope tag (K119; see Fig. 1). To identify the site of action of HMDC, mutant proteins with a replacement K22R were constructed on the background of the wild-type EmrE (Fig. 2B, lane 4) and in EmrE-His, containing the additional K119 (lane 3). Both mutants produced only a borderline amount of dimer after HMDC reaction, as monitored on reducing SDS/PAGE. Wild-type EmrE (Fig. 2B, lane 5) and EmrE-His (Fig. 2A, lane 3) crosslink with HMDC. Therefore, the major site of action of HMDC is likely to be K22 rather than K119.

Fig 2.

(A) Denaturation prevents intermonomer crosslinking in EmrE. 35S-labeled CL-EmrE-His-K22C (lanes 1 and 2) or CL-EmrE-His (lanes 3 and 4) membranes were treated with 100 μM o-PDM or 0.2% HMDC reagent, respectively, in 0.8% DDM-Na buffer (lanes 1 and 3) or SDS-urea buffer (lanes 2 and 4). (B) HMDC crosslinking of DDM-solubilized EmrE mutants. DDM-solubilized membranes from the following mutants radiolabeled with 35S were analyzed after treatment with 0.2% HMDC. Lane 1, EmrE-K22C; lane 2, CLA-EmrE-His K22C; lane 3, EmrE-His K22R; lane 4, EmrE-K22R; lane 5, EmrE.

Although cysteine residues may also react with HMDC, no crosslinking was observed with those that were membrane-embedded (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 4). We therefore tested the reaction in a mutant in which K22 was replaced with cysteine in wild-type background (Fig. 2B, lane 1) and in a CLA-EmrE-His background (lane 2). Quantitative crosslinking was observed, demonstrating that HMDC also reacts with solvent-exposed cysteine residues. Despite its high hydrophobicity, it does not react with the native cysteines buried in the membrane domains.

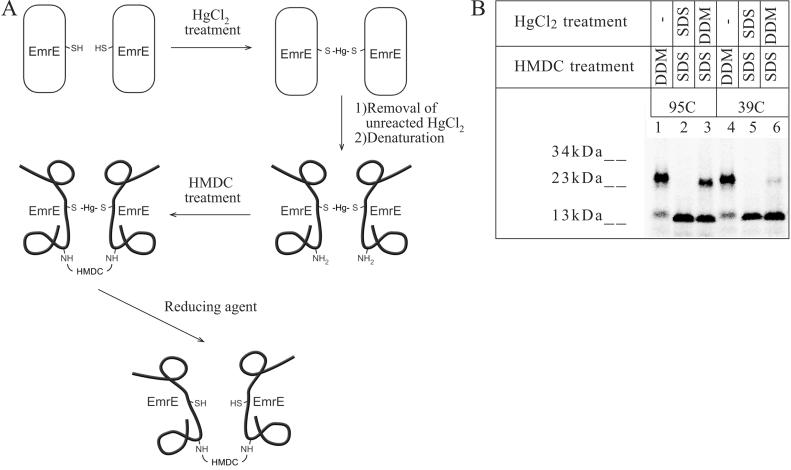

The above findings supported the assumption that the HMDC crosslinking step can provide us with a “snapshot” of the crosslinking status because it does not react with the SDS-urea dissociated oligomer. Thus, a protocol was designed where after the initial crosslinking with HgCl2, the excess reagent was removed using a Sephadex G25 desalting column. The protein samples were denatured in SDS-urea buffer so that noncrosslinked monomers dissociate, and only mercury- linked pairs remain as dimers. Denatured protein samples were treated with the second crosslinker HMDC. As we showed above, under denaturing conditions, only the previously linked monomers would undergo crosslinking with HMDC. Before separation on reducing SDS/PAGE, reagents were scavenged with 1.5% 2-mercaptoethanol (see flow sheet in Fig. 3A).

Fig 3.

HgCl2 crosslinking of DDM-solubilized protein followed by denaturation and HMDC crosslinking. (A) Experimental scheme flow sheet: [35S]EmrE unique cysteine replacements were solubilized in 0.8% DDM and treated with 50 μM HgCl2. After removal of the unreacted HgCl2, denaturation in SDS-urea buffer dissociated oligomers that did not crosslink. The second crosslinking was performed with 0.2% HMDC. Samples were reduced with 1.5% 2-mercaptoethanol and assayed by SDS/PAGE. (B) DDM-solubilized membranes of CL-95C (lanes 1–3) or CL-39C (lanes 4–6) were crosslinked with HgCl2, denatured with SDS-urea buffer, and further treated with HMDC (lanes 3 and 6, respectively) as described in Experimental Procedures and schematically in A. Controls with HMDC alone are shown in lanes 1 and 4. Controls where the HgCl2 crosslinking was performed under denaturing conditions are shown in lanes 2 and 5.

The results of the combined approach (HgCl2/HMDC) are demonstrated in Fig. 3B for two residues: 95C, which showed substantial crosslinking (lane 3), and 39C, where no significant crosslinking was detected (lane 6). Controls were performed for each unique cysteine replacement by solubilization of the membranes in denaturing buffer before HgCl2 treatment (lanes 2 and 5) and the positive control for the HMDC reaction (no HgCl2) was performed by HMDC crosslinking on a sample in the nondenaturing buffer (lanes 1 and 4).

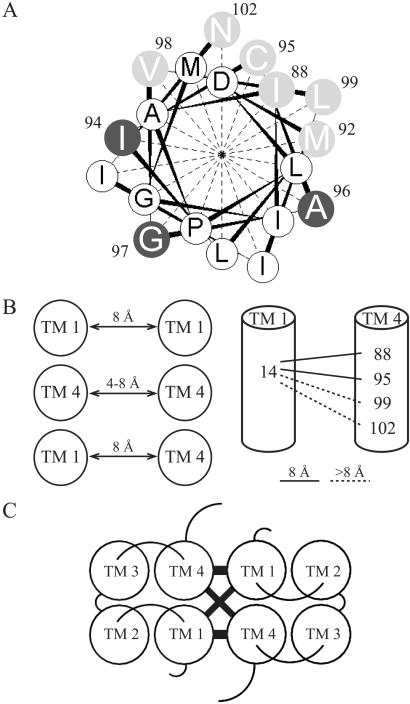

Contact Points in TM4.

The above-described protocol was applied to several single cysteine substitutions. For this purpose, we used mutant proteins with unique cysteine replacements engineered into appropriate positions. Previous work with EmrE has shown this approach feasible because a large number of mutants are functional (15). In the case of TM4, nine different unique replacements were used (Table 1). The following produced substantial amounts of the dimer when subjected to HgCl2 crosslinking: I88C, M92C, C95, V98C, L99C, and N102C. Whereas I94C and A96C yield borderline amounts of dimer, G97C is clearly negative. The positions where cysteine replacements led to significant crosslinking were restricted to one face of TM4 (see Fig. 5A and Discussion).

Table 1.

Crosslinking detected in TM4 unique cysteine replacements by using o-PDM and HgCl2

| Unique cysteine replacement

|

Reagent | |

|---|---|---|

| o-PDM | HgCl2 | |

| I88C | <5 | 27 |

| M92C | 0 | 33 |

| I94C | 0 | <5 |

| C95 | 0 | 32 |

| A96C | 0 | <5 |

| G97C | 0 | 0 |

| V98C | <5 | 38 |

| L99C | 10 | 32 |

| N102C | 12 | 39 |

The amount of dimer is shown as percent of the total radioactivity detected in the polypeptide with SDS/PAGE mobility corresponding to ≈30 kDa after reaction with 100 μM o-PDM or 50 μM HgCl2. Percentages of dimer for significant and reproducible low crosslinking yields are presented as lower than 5%.

Fig 5.

(A) Helical wheel projection of TM4. Positions that produced dimer on crosslinking with HgCl2 are labeled in gray. Those that did not form dimer are labeled black. Residues in white were not tested. (B) Summary of the experimental constraints determined by crosslinking in this work. The TMs are represented by circles and the distances are from o-PDM (8 Å) or from Hg2+ (4 Å) crosslinking. On the right side, the results with the hetero-oligomers are summarized. Negative crosslinking results indicate a distance larger than 8 Å. (C) Helix packing model of the EmrE dimer. Two monomers are shown where the TMs are represented with circles and the loops with curved lines. The helical contacts determined in this work are marked with straight thick lines.

Domains in TM4 Exposed to Aqueous Environment.

It was previously shown that membrane-embedded residues do not react with water-soluble sulfhydryl reagents, and we suggested that this is due to lack of accessibility or reactivity or both (15). Even the hydrophobic reagent o-PDM reacted only with residues in solvent-exposed positions of TM4, close to the beginning and the end of the TM (Table 1). Thus, mutant proteins with unique cysteine replacements N102C and L99C yielded significant amounts of dimer (see also Fig. 4, lanes 1–4). V98C and I88C produced marginal but significant crosslinking, whereas others (M92C, I94C, C95, A96C, and G97C) were negative (Table 1). As demonstrated in Table 1, o-PDM is less efficient than Hg++ in the crosslinking yield. Thus, for example, whereas o-PDM generates only 10–12% dimers with L99C and N102C, Hg++ produces more than 30%. These results, while in basic agreement with the Hg++ crosslinking, further highlight the utility of the latter technique in crosslinking cysteine in a low-dielectric medium.

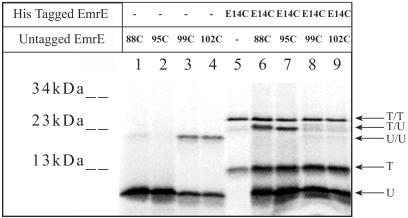

Fig 4.

Intermonomer crosslinking between different unique cysteine replacements of EmrE. The indicated 35S-untagged unique cysteine replacements were crosslinked with 100 μM o-PDM without (lanes 1–4) or with mixing with [35S]E14C EmrE-His (lanes 6–9). Lane 5 shows the crosslinking in the [35S]E14C EmrE-His oligomer. U, untagged; T, tagged.

Crosslinking in TM1 Residues.

In the case of residues in TM1, only the E14C mutant produced a significant amount of dimers when subjected to o-PDM (Table 2). Residues in the same face of the helix (L7C, A10C, I11C, and T18C) yield reproducible but low amounts of dimer, whereas L12C and I16C, facing the other face of the helix, show no detectable crosslinking. The low crosslinking efficiency may reflect inaccessibility of the reagent, a low dielectric, or both. Efforts to improve the efficiency were performed to no avail by increasing the o-PDM concentration to 400 μM and increasing the temperature of the crosslinking reaction to 37°C (data not shown).

Table 2.

Crosslinking detected in EmrE unique cysteine replacements by using o-PDM

| Unique cysteine replacement | o-PDM |

|---|---|

| TM1 | |

| L7C | <5 |

| A10C | <5 |

| I11C | <5 |

| L12C | 0 |

| E14C | 35 |

| I16C | 0 |

| T18C | <5 |

| Loops | |

| K22C | 35 |

| G57C | 38 |

| L83C | 0 |

| H110C | 48 |

The amount of dimer is shown as percent of the total radioactivity detected in the polypeptide with SDS/PAGE mobility corresponding to ≈30 kDa after reaction with 100 μM o-PDM.

TM1 was subjected to mercury crosslinking as well. Also with this treatment only the unique cysteine replacement at position 14 yields a large amount of the dimer when subjected to HgCl2 crosslinking (about 40%). None of the other residues in TM1 yielded significant HgCl2 crosslinking.

The glutamyl residue at position 14 is membrane-embedded and an essential part of the binding site and the coupling mechanism (6, 21). The cysteine replacement at this position is not functional. The fact that a cysteine replacement at this position is capable of reacting with o-PDM suggests a domain with a dielectric constant that allows for ionization to the more reactive thiolate anion. The conclusions that can be reached with inactive mutants are limited. However, hetero-oligomers between E14C and a cysteine-less EmrE protein display binding of TPP+ (10). The cysteine residue at position 14 in this functional hetero-oligomer reacts with N-ethylmaleimide (10) and with thiosulfonate derivatives (D. Rotem, M. Sharoni, and S.S., unpublished results), supporting the finding that the reaction with o-PDM reflects a property that is present also in the functional protein.

These results raise the necessity to seek further lines of evidence for the proximity of TM1 of two different monomers and this is further discussed below.

Loops.

K22C, in the first loop, was shown above to crosslink with HMDC. To further test the proximity of the K22 residues in two neighboring monomers, the unique cysteine replacement K22C was challenged with o-PDM. This mutant in DDM yielded high amounts of dimer (Fig. 2A, lane 1). Denaturation prevented crosslinking (lane 2).

Three residues in each of the other loops and in the C terminus were treated with o-PDM (Table 2). There was substantial crosslinking of mutants G57C and H110C, but no crosslinking of L83C.

Intermonomer Crosslinking Between Different Unique Cysteine Replacements.

The experiments described above provide us with a set of constraints based on the use of the same residues in two identical monomers. As mentioned above, we have developed techniques to swap monomers and generate hetero-oligomers. EmrE-His and untagged EmrE display both in their monomeric and dimeric form clearly distinguishable electrophoretic mobilities (compare lanes 2 and 5 in Fig. 2B and lanes 1–4 in Fig. 4 with lanes 5–9 in Fig. 4). SDS/PAGE resolution was also sufficient to distinguish between tagged/tagged (T/T), tagged/untagged (T/U), and untagged/untagged (U/U) crosslinked dimers on the SDS/PAGE (Fig. 4). Untagged proteins (lanes 1–4) were prepared by trypsinization of tagged EmrE with unique cysteine replacements. This is possible because of total resistance of EmrE to proteolysis both in the membrane and in DDM solutions (unpublished results). As reported in Table 1, o-PDM crosslinks cysteines in positions 99 and 102, but not in 88 and 95 (lanes 1–4). Mixed oligomers between E14C-CLA-EmrE-His and the four untagged monomers were prepared as described above and subjected to o-PDM crosslinking. After reaction with o-PDM, four species with different mobilities are distinguished: (i) monomeric untagged proteins (U); (ii) monomeric tagged protein (T); (iii) tagged/tagged dimers formed by the only tagged protein added E14C (T/T); and (iv) mixed oligomers (T/U) formed between E14C and I88C (lane 6) or C95 (lane 7), but not between E14C and either L99C or N102C (lanes 8 and 9). The untagged/untagged dimers visible before (lanes 3 and 4) are not observed when crosslinking is performed with the hetero-oligomers (lanes 8 and 9). This is because a 2-fold excess of E14C is used in these experiments to optimize the heterocrosslinks. Under these conditions, the likelihood of untagged/untagged crosslinks was decreased significantly. These results demonstrate the proximity between TM1 of the first monomer and TM4 of the second monomer.

Discussion

This study provides a protocol for crosslinking cysteine residues in environments with low dielectric constants. The experiments with EmrE identified vicinal residues in distinct monomers of the EmrE oligomer.

This protocol was essential for EmrE because most of its residues do not react with a series of hydrophilic reagents we have tested. It should also be useful for other proteins with cysteine residues in low dielectric environments. The protocol is based on the use of HgCl2, a well known sulfhydryl reagent that poses serious problems for crosslinking studies because of its extremely high reactivity and reversibility, and because of its relatively complex chemistry. It can react with a single cysteine and form a stable intermediate. This intermediate can further react with a second cysteine to form the –S–Hg–S–. This compound can also undergo rearrangements and it dissociates under reducing conditions. On the other hand, the major advantage of HgCl2 is its high reactivity even with membrane-embedded residues and the very short distances it probes as compared with other crosslinkers. It is estimated that the distance for two sulfhydryls to react must be in the range of 4–5 Å. A second crosslinker, HMDC, is used after the HgCl2-treated oligomers are dissociated with SDS-urea buffer. Although it can react with residues that are up to 15 Å apart, HMDC does not react with the SDS-urea dissociated oligomer unless it was previously crosslinked. After HMDC treatment, 2-mercaptoethanol is added to quench the unreacted HMDC and reduce the S-Hg and S-Hg-S bonds. This allows the use of SDS/PAGE to identify the residues that reacted with HgCl2.

In the case of EmrE, HMDC behaves as a specific crosslinker that reacts only with K22. This finding may also point to a limitation of its use. It is possible that some mutants yield negative results because of geometrical constraints. Thus, if Hg++ crosslinks a residue that is far away from K22, denaturation could bring the HMDC reacting residues from each monomer too far apart. However, in the case of the TM4 residues scanned, crosslinking efficiency with Hg++ did not decrease with the distance from K22, proving that even in the denatured sample, the distances are still compatible with crosslinking by HMDC.

Both HgCl2 and o-PDM reaction patterns with unique cysteine replacements in TM4 are, in general, in good agreement. The lower efficiency of crosslinking with o-PDM is not only because of its lower reactivity. Crosslinking of two neighbor cysteine residues with one o-PDM molecule competes with two reactions: (i) labeling of the two cysteine with different o-PDM molecules; and (ii) hydrolysis of one of the maleimide moieties in o-PDM either before or after reaction with cysteine.

o-PDM is limited because it does not react with most membrane-embedded residues and therefore most valuable information in this respect is provided by HgCl2. In the case of TM4, the efficiency of crosslinking of the reactive residues along the TM is very similar, suggesting an extended contact zone along the helices and a very low relative tilt angle. In the case of TM1, the results are quite different. We previously proposed that the unusually high pK displayed by Glu-14 might be due to a very close proximity of the carboxyl residues in different monomers. In this work, using two different crosslinkers, we demonstrate that the cysteine replacements at position 14 are indeed in close proximity to the corresponding residue in the neighboring monomer. It is also noteworthy that the cysteine replacement at this position is the only membrane-embedded replacement that was shown to react with maleimide derivatives. This finding suggests that the environment near residue 14 allows for higher amounts of the more reactive thiolate anion. The distances for the other residues in TM1 may be also compatible for crosslinking with o-PDM, but limited by accessibility or by the low amount of thiolate anion. However, the cysteine replacement at position 14 is the only one in TM1 that reacts with Hg++. These results may suggest a slightly x-shaped structure for the TM1 oligomer where cysteine residues at position 14 are the only ones close enough to react. The fact that E14C, a nonfunctional mutant, is the only one to react in TM1 necessitates further experimentation to demonstrate TM1–TM1 proximity. Nevertheless, there is evidence that this mutant protein maintains a structure that may be similar to the wild type. This is based on the finding that the hetero-oligomer E14C-wild type is functional (albeit with a lower affinity). In addition, in this hetero-oligomer, the cysteine residues at position 14 react with maleimide (10). Furthermore, the highly efficient crosslinking of K22, the first residue in the loop after TM1, substantiates the proximity of TM1 in neighbor monomers.

The experiments presented in this work were performed with DDM-solubilized protein. However, there is no strict requirement to either solubilize or purify the protein. Several experiments were performed with some of the mutants also without solubilization and qualitatively similar results were obtained (not shown). The findings imply that the technique could be used also in the membrane with proteins that do not maintain their structure after solubilization. In addition, these findings support again the contention that the DDM-solubilized protein displays a structure very similar to the one in the membrane. We previously showed that it binds substrates with very high affinity (1) and here we demonstrate a very stable dimeric structure. This was suggested in previous studies in which practically no monomer mixing was detected unless the oligomer was previously dissociated (10).

The experiments designed here were capable only of detecting dimers because a single cysteine residue was present in each monomer. Efforts to demonstrate higher oligomeric entities were made by engineering additional cysteine residues in the loops of a K22C mutant protein. However, only dimers were observed in the constructs tested.

The results presented supply some experimental constraints for helix-packing models (Fig. 5B). We do not have yet any information on the tilt of specific helices and on helix assignment in our two-dimensional crystals. Therefore, the only model we can put forward at present is the simplest and one in which the helices are perpendicular to the membrane, an assumption that we know to be inaccurate (8, 24). This model (Fig. 5C) is a first approximation and it provides us with predictions that can be experimentally tested. It does not explain the observed asymmetry in the two-dimensional crystals. It does not offer a simple explanation for crosslinking at position 57. The model stresses the central role of Glu-14 in substrate recognition and translocation, and predicts that other residues in the same face of the TM1 helix and in TM4 play significant roles in the catalytic cycle.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche–Israeli Program [Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research (BMBF)–International Bureau at the German Aerospace Center Technology], National Institutes of Health Grant NS16708, and Israel Science Foundation Grant 463/00.

Abbreviations

TM, transmembrane domain

DDM, n-dodecyl-β-maltoside

TPP+, tetraphenylphosphonium

HMDC, hexamethylene diisocyanate

o-PDM, o-phenylene dimaleimide

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

The mutants are named as follows: single amino acid replacements are named with the letter of the original amino acid, then its position in the protein and the letter of the new amino acid.

References

- 1.Muth T. R. & Schuldiner, S. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 234-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuldiner S., Granot, D., Mordoch, S. S., Ninio, S., Rotem, D., Soskin, M., Tate, C. G. & Yerushalmi, H. (2001) News Physiol. Sci. 16, 130-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuldiner S., Granot, D., Steiner, S., Ninio, S., Rotem, D., Soskin, M. & Yerushalmi, H. (2001) J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 3, 155-162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yerushalmi H., Lebendiker, M. & Schuldiner, S. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 6856-6863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ninio S., Rotem, D. & Schuldiner, S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 48250-48256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yerushalmi H. & Schuldiner, S. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 14711-14719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yerushalmi H. & Schuldiner, S. (2000) FEBS Lett. 476, 93-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tate C. G., Kunji, E. R., Lebendiker, M. & Schuldiner, S. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 77-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yerushalmi H., Lebendiker, M. & Schuldiner, S. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 31044-31048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rotem D., Sal-Man, N. & Schuldiner, S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 48243-48249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu J. H., Hardy, D. & Kaback, H. R. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 15785-15790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu J., Hardy, D. & Kaback, H. (1998) J. Mol. Biol. 282, 959-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim Y.-M., Ye, L. & Maloney, P. C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36681-36686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Montfort B. A., Schuurman-Wolters, G. K., Wind, J., Broos, J., Robillard, G. T. & Poolman, B. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 14717-14723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mordoch S. S., Granot, D., Lebendiker, M. & Schuldiner, S. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 19480-19486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lebendiker M. & Schuldiner, S. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21193-21199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnon R. & Shapira, E. (1969) J. Biol. Chem. 244, 1033-1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yanish-Perron C., Viera, J. & Messing, J. (1985) Gene 33, 103-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg E. B., Arbel, T., Chen, J., Karpel, R., Mackie, G. A., Schuldiner, S. & Padan, E. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84, 2615-2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tabor S. & Richardson, C. (1985) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82, 1074-1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yerushalmi H. & Schuldiner, S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 5264-5269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho S. F., Hunt, H. D., Horton, R. M., Pullen, J. K. & Pease, L. R. (1989) Gene 77, 51-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schagger H. & von Jagow, G. (1987) Anal. Biochem. 166, 368-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arkin I. T., Russ, W. P., Lebendiker, M. & Schuldiner, S. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 7233-7238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]