Abstract

The S–M checkpoint delays mitosis until DNA replication is complete; cells defective in this checkpoint lose viability when DNA replication is inhibited. This inviability can be suppressed in fission yeast by overexpression of Cid1 or the related protein Cid13. Fission yeast contain six cid1/cid13-like genes, whereas budding yeast has just two, TRF4 and TRF5. Trf4 and Trf5 were recently reported to comprise an essential DNA polymerase activity required for the establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. In contrast, we find that Cid1 is not a DNA polymerase but instead uses RNA substrates and has poly(A) polymerase activity. Unlike the previously characterized yeast poly(A) polymerase, which is a nuclear enzyme, Cid1 and Cid13 are constitutively cytoplasmic. Cid1 has a degree of substrate specificity in vitro, consistent with the notion that it targets a subset of cytoplasmic mRNAs for polyadenylation in vivo, hence increasing their stability and/or efficiency of translation. Preferred Cid1 targets presumably include mRNAs encoding components of the S–M checkpoint, whereas Cid13 targets are likely to be involved in dNTP metabolism. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation is known to be an important regulatory mechanism during early development in animals. Our findings in yeast suggest that this level of gene regulation is of more general significance in eukaryotic cells.

After exposure to hydroxyurea (HU), an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase, eukaryotic cells arrest in S phase and do not enter mitosis, owing to the activation of the DNA replication (S–M) checkpoint. In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, loss of function of S–M checkpoint genes such as rad3 does not impair normal growth but results in rapid loss of viability when cells are exposed to HU (1). Rad3 is a large protein kinase related to the vertebrate proteins ATR and ATM that, like Rad3, are required for S–M and DNA damage checkpoint responses (2). These checkpoints arrest the cell cycle to allow time for repair of damaged DNA or completion of DNA replication.

During DNA replication, cohesion is established between newly replicated sister chromatids, which are held together by the multiprotein complex cohesin (3). Maintenance of sister chromatid cohesion from S phase through G2 and until the onset of anaphase is necessary for accurate chromosome segregation. Cohesion is also important for efficient DNA repair, as it ensures that the undamaged sister chromatid is positioned to serve as a template for repair by homologous recombination. The mechanism by which cohesion is established during S phase is unknown. Recent data suggest that Trf4 and Trf5, two closely related proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, act as a DNA polymerase to couple cohesion to replication, possibly directly by replicating sites of cohesion (4). The S. pombe genome contains six TRF4/5 related genes: cid1, cid11, cid12, cid13, cid14, and cid16.

S. pombe cid1 is required for S–M checkpoint integrity when DNA polymerase (Pol) δ or ɛ is inhibited (5). Overexpression of cid1 confers resistance to a combination of HU and caffeine, which inhibits the S–M checkpoint (6). Cid1–Cid16, Trf4, and Trf5 are members of the Pol β family of nucleotidyl transferases (7). It initially seemed plausible that cid1 might also encode a Pol, possibly related to the establishment of cohesion. However, alternative biochemical functions for Cid1 could not be ruled out. Other members of the Pol β superfamily are known to transfer nucleotidyl residues to proteins, RNAs, or antibiotics (7), and Cid1 lacks analogues of the thumb and finger domains of Pol β that wrap around the DNA substrate (8).

Here, we show that Cid1 has poly(A) polymerase activity and describe the isolation of cid13+ as a suppressor of the HU sensitivity of a rad3 mutant. We show that Cid1 and Cid13 constitutively localize to the cytoplasm, suggesting that their targets are also cytoplasmic.

Materials and Methods

Fission Yeast Strains and Methods.

Conditions for growth, maintenance, and genetic manipulation of fission yeast were as described (9). Strains cid13Δ (cid13:ura4 or cid13:LEU2), cid13:Myc, cid1:HA, and cid1:GFP were constructed in this study. All other strains have been described (1, 5, 10). For gene disruption and tagging, the one-step targeted recombination method was used (11), following PCR-mediated generation of linear DNA fragments marked with ura4+, LEU2, or kanMX.

The genomic library screen for suppressors of rad3ts HU sensitivity has been described (10). The cid13 insert contained a single ORF originally designated SPAC821.04c and now named cid13, according to the nomenclature established for cid1, cid11, and cid12 (5). Subclones were capable of suppressing the HU sensitivity of rad3ts cells only if they contained the whole cid13 ORF. Multiple sequence alignments were generated by using CLUSTALX software (National Center for Biotechnology Information) and the following parameters: gap opening, 10.0; gap extension, 0.05.

S. pombe protein extract preparation, immunoblotting, anti-Cds1 immunoprecipitations, and Cds1 kinase assays were performed as described (12). Immunostaining with anti-Myc antibody 9E10 was performed by using the general method described (13).

Purification of Recombinant Cid1.

cDNAs encoding Cid1 or Cid1DADA (Cid1 with aspartate residues 101 and 103 replaced by alanine) were cloned into pET30a (Invitrogen), transformed into Escherichia coli BL21, and expression of the recombinant protein was induced by using 0.3 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were lysed by sonication on ice in 20 mM Tris, pH 8/20 mM imidazole/500 mM NaCl/8% glycerol with protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche). The lysate was cleared by centrifugation and filtration through a Millex-HA 0.45-μm filter (Millipore), before being loaded onto an Ni2+ charged chromatography column (POROS MC20) using a BioCAD workstation. The column was washed with 20 mM imidazole, and His-6Cid1/Cid1DADA was eluted with an imidazole gradient (50–500 mM over 10 ml). The majority of the protein eluted in a narrow peak across four 1-ml fractions. The identity of each protein was confirmed by using anti-His-6 immunoblotting and N-terminal sequencing.

ATPase and Pol Assays.

ATPase activity was determined by thin-layer chromatography following release of 32P from [γ-32P]ATP, as described (14). Primers for Pol assays were 5′ labeled by using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Roche) and [γ-32P]ATP. A 2-fold excess of the oligonucleotide template (0.02 pmol) was annealed with one equivalent of the oligonucleotide primer (0.01 pmol) in 30 μl of 1 × Expand PCR buffer (Roche) by slow cooling from 96°C to room temperature. The DNA was then ethanol precipitated and resuspended in 20 μl of TE buffer. Pol reactions (10 μl) contained 25 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7/5 mM MgCl2/5 mM DTT/100 μg/ml BSA/10% glycerol/100 μM dNTPs/10 nM labeled annealed primer/template/200 ng of protein. Reactions were incubated at 30°C for 30 min and stopped by the addition of two volumes of 50 mM EDTA/1% SDS. DNA was ethanol precipitated, resuspended in 90% formamide loading buffer, subjected to 8 M urea/15% PAGE, and visualized by using a Storm phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics).

RNA Polymerase Assays.

Template-independent polyadenylation assays were carried out as described (15). Reactions with radiolabeled cordycepin 5′-triphosphate and extension of radiolabeled RNA oligonucleotides using NTPs were measured under the same conditions. Reactions (20 μl) contained 20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 0.7 mM MnCl2, 15 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 100 μg/ml acetylated BSA, 10% glycerol, 5 μl of RNA (1.5 μg), and 1–5 μl of poly(A) polymerase (United States Biochemical, Amersham Pharmacia), Cid1, or Cid1DADA. Reaction products were separated by 7M urea/6% PAGE in 1 × TBE.

Results

Cid1 Is a Poly(A) Polymerase.

The Pol β superfamily to which Cid1 belongs is characterized by the sequence motif hG[G/S]X9–13Dh[D/E]h (where X = any amino acid, h = hydrophobic residue), which is a reliable predictor of nucleotidyl transferase activity (7). We therefore decided to characterize the nucleotidyl transferase activity of recombinant Cid1 protein in vitro.

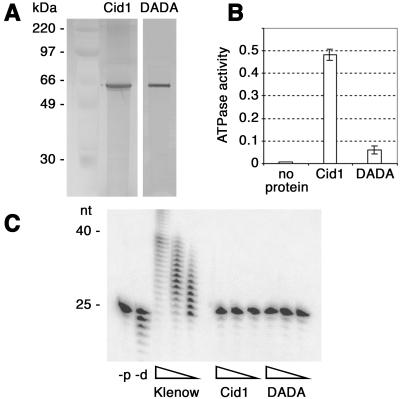

Hexahistidine-tagged Cid1 was expressed in E. coli and purified by nickel chelate chromatography. We previously generated a cDNA (Cid1DADA) encoding Cid1 with aspartate residues 101 and 103 replaced by alanine (5). The equivalent residues are known to be essential for catalysis in Pol β and poly(A) polymerase (8, 16). Recombinant Cid1DADA was therefore purified to provide a negative control. On SDS/PAGE, both proteins migrated at ≈55 kDa, and silver staining showed that they had been purified to apparent homogeneity (Fig. 1A). As a putative nucleotidyl transferase, Cid1 might be expected to possess ATPase activity, even in the absence of a nucleotidyl recipient substrate. Cid1 hydrolyzed ATP in vitro, and whereas this ATPase activity was relatively modest, recombinant Cid1DADA under the same conditions exhibited ATPase activity close to background (Fig. 1B). ATP hydrolysis by Cid1 was maximal in the presence of 2.5 mM Mg2+, although activity was also detected in the presence of other divalent metal ions (data not shown).

Fig 1.

Recombinant Cid1 is an ATPase but lacks Pol activity. (A) Purified recombinant Cid1 and Cid1DADA were separated by SDS/PAGE and silver-stained. The sizes of the molecular mass markers in the lane next to Cid1 are indicated on the left. (B) ATPase activities (μmol min−1) in the presence of no added protein or 250 ng of recombinant Cid1 or Cid1DADA, as indicated; the average of three independent determinations is shown graphically (error bars represent one standard deviation). (C) In vitro Pol assays were performed by using a dT25/dA40 substrate and 5-fold serial dilutions of E. coli PolI large fragment (Klenow), Cid1, or Cid1DADA as indicated. Control reactions included either no added protein (−p) or Klenow enzyme in the absence of added dNTPs (−d). The sizes of reaction products in nucleotides are indicated on the left.

To address the possibility that Cid1 might have Pol activity, we assayed recombinant Cid1 and Cid1DADA by using the method previously used to demonstrate that hexahistidine-tagged recombinant Trf4 (Pol σ) is a Pol (4). The large fragment of E. coli Pol I, used as a positive control in these assays, was able to extend the dT25 primer efficiently. In contrast, neither recombinant Cid1 nor Cid1DADA exhibited any detectable Pol activity under these conditions (Fig. 1C).

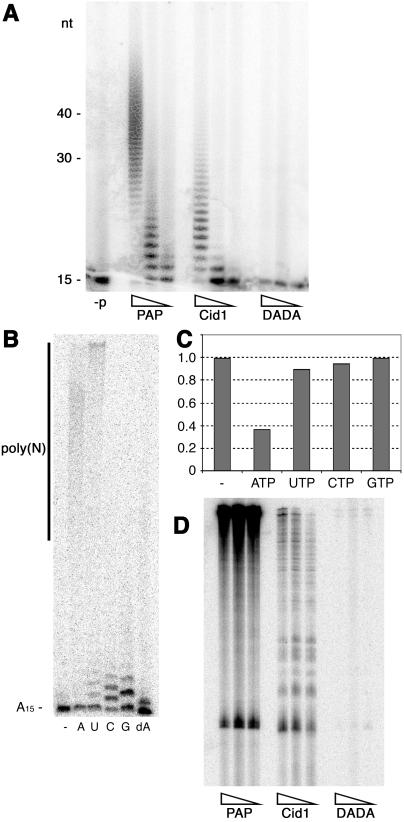

The Pol β superfamily includes the RNA nucleotidyl transferase poly(A) polymerase, which, at the primary sequence level, is more closely related to Cid1 than is Pol β. To test whether Cid1 has poly(A) polymerase activity in vitro, we incubated recombinant Cid1 with a 32P-labeled synthetic RNA substrate (A15) in the presence of ATP. Cid1, but not Cid1DADA, extended the 32P-A15 substrate in a dose-dependent manner to generate a distribution of products qualitatively similar to that generated by S. cerevisiae poly(A) polymerase (Fig. 2A). Cid1 incorporated ≈0.46 nmol of AMP/mg every 10 min under the reaction conditions used, a specific activity ≈5% of that of the commercially sourced S. cerevisiae poly(A) polymerase. Previously characterized poly(A) polymerases have a high degree of specificity for ATP in comparison with other nucleotide triphosphates. In the in vitro poly(A) polymerase assay, Cid1 was able to use either ATP or UTP as the donor for processive nucleotidyl transfer, but with GTP, CTP, or dATP, only one to three residues were incorporated (Fig. 2B). The synthesis of poly(U) tracts by Cid1 in vitro indicates that Cid1 does not share the high selectivity for ATP that is characteristic of nuclear poly(A) polymerases. However, in the ATPase assay, Cid1 preferentially hydrolyzed ATP in the presence of competing NTPs (Fig. 2C), indicating that in vivo, where ATP is likely to be at least 5-fold more abundant than UTP, Cid1 may be sufficiently selective for ATP to allow it to function primarily or solely as a poly(A) polymerase. Unlike nuclear poly(A) polymerase, Cid1 was not appreciably stimulated by Mn2+ (data not shown).

Fig 2.

Cid1 is a poly(A) polymerase. (A) In vitro poly(A) polymerase assays were performed by using 50, 5, and 0.5 ng of S. cerevisiae poly(A) polymerase (PAP), and 200, 40, and 8 ng of Cid1 or Cid1DADA, as indicated, and a radiolabeled A15 RNA substrate for 10 min at 30°C. A control reaction included no added protein (−p). The sizes of reaction products in nucleotides are indicated on the left. (B) Poly(A) polymerase assays were performed for 30 min at 30°C by using 400 ng of Cid1 and ATP (A), UTP (U), CTP (C), GTP (G), dATP (dA), or no added nucleotide triphosphate (−). (C) Cid1 ATPase assays were performed as in Fig. 1B (−) or with the addition of a 5-fold molar excess of each of the unlabeled NTPs indicated. (D) Poly(A) polymerase assays were performed as in A, but using 2-fold serial dilutions of each enzyme, total S. pombe RNA, and [α-32P]cordycepin 5′-triphosphate.

To investigate whether Cid1 might have inherent substrate specificity when presented with a complex mixture of RNA molecules, we incubated total S. pombe RNA with Cid1, Cid1DADA, or S. cerevisiae poly(A) polymerase, in the presence of the chain terminating nucleotide [α-32P]cordycepin 5′-triphosphate (3′ deoxy-ATP). In comparison with S. cerevisiae poly(A) polymerase, which was able to end-label a continuous smear of RNA species under these conditions, Cid1 appeared to target a subset of S. pombe RNAs preferentially (Fig. 2D). Cid1 was able to extend synthetic RNA oligonucleotides with different 3′ nucleotides with similar efficiencies (data not shown). This could indicate that Cid1 does not preferentially extend preexisting poly(A) tails in vivo; alternatively, specificity for polyadenylated substrates might be conferred by interaction with other factors.

cid13 Suppresses rad3ts HU Sensitivity.

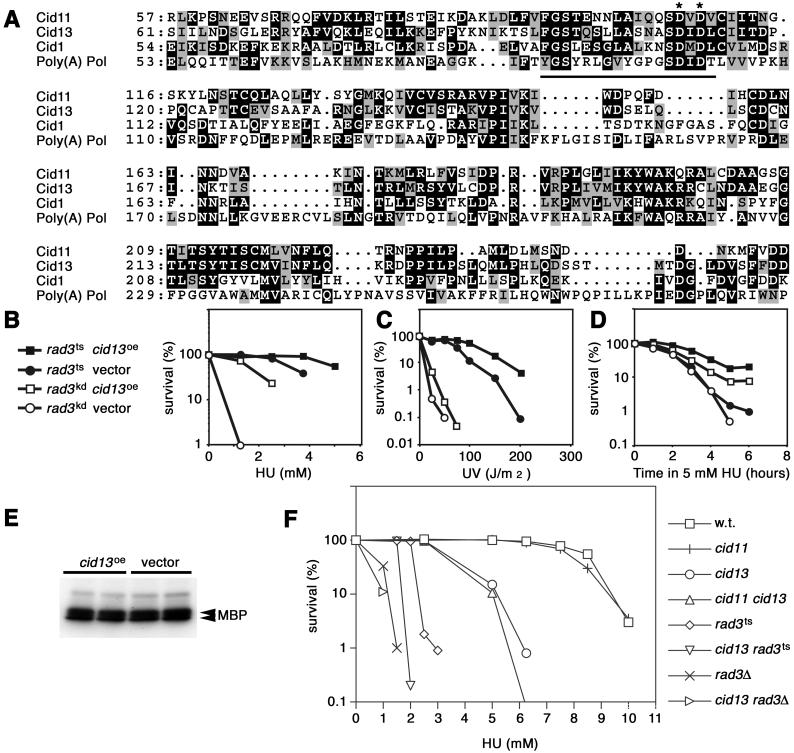

We have shown that overexpression of cid1 partially suppresses the HU sensitivity of rad3 mutants (5). To identify additional components with related functions, we used an S. pombe genomic library to identify multicopy suppressors of the HU sensitivity conferred by partial loss of Rad3 function in a rad3ts strain (10). This screen identified the gene cid13, as well as those encoding Suc22, the small subunit of ribonucleotide reductase, and Cds1, the checkpoint kinase that acts downstream of Rad3 in the S–M checkpoint. The cid13 ORF encodes a 65-kDa protein of 579 aa residues with 31% identity to Cid1 (51% similarity) between amino acid residues 56 and 356 (Fig. 3A). Protein family (Pfam) domain structure analysis indicated that Cid13 contains a poly(A) polymerase-related domain (PAP/25A core domain) between residues 91 and 232 and a PAP/25A-associated domain between residues 275 and 336. Overexpression of cid13 (cid13oe) partially suppressed the HU and UV sensitivities both of rad3ts and of the rad3kd (kinase dead) strain, which is defective in checkpoint signaling to the same extent as a rad3 deletion (Fig. 3 B–D). Thus, cid13oe may function as a bypass suppressor of rad3 loss of function. Rad3 activates the downstream protein kinase Cds1 when DNA replication is inhibited. To determine whether cid13oe bypasses Rad3 and also bypasses activation of Cds1, we assessed Cds1 kinase activity in rad3ts cells containing either the cid13 plasmid or the empty vector, after incubation in HU at 32°C (Fig. 3E). There was no significant difference between the Cds1 activities in these extracts, supporting the notion that Cid13 suppresses the Rad3 defect by a bypass mechanism.

Fig 3.

Cid13 is a Cid1- and poly(A) polymerase-related protein that suppresses the HU sensitivity of rad3 mutants. (A) Alignment of amino acid sequences of the putative catalytic cores of Cid1, Cid11, Cid13, and S. pombe poly(A) polymerase. Amino acid residue numbers are indicated to the left of each sequence, conserved residues are highlighted on a black background, and conservative substitutions are shaded. The Pol β superfamily motif is underlined, and the two conserved aspartate residues changed to alanine in the Cid1 DADA mutant are indicated by asterisks. (B and C) Survival of rad3ts or rad3kd cells transformed with pUR-cid13 (cid13oe) or pUR (vector), as indicated, after plating onto agar containing various doses of HU (B) or after UV irradiation on agar plates (C). Survival was scored by counting colonies after 4 days of incubation at 32°C. (D) Survival of the same strains after short-term exposure to 5 mM HU in liquid culture at 32.5°C. Aliquots of cells taken at the times indicated were scored for viability by plating onto agar lacking HU and incubation at 32°C for 3 days. (E) Cells of the rad3ts strain transformed with pUR-cid13 (cid13oe) or pUR (vector), as indicated, were exposed to 5 mM HU at 32°C in duplicate liquid cultures for 3 h and were then assayed for Cds1 kinase activity in vitro using myelin basic protein (MBP) as substrate. (F) The strains indicated were inoculated onto plates containing various doses of HU, and survival was scored by counting colonies after 4–5 days of incubation at 32°C.

Of all known gene products, Cid13 is most closely related to Cid11 of S. pombe. We therefore examined the relationship between cid13 and cid11. Multicopy plasmid expression of a genomic cid11 clone did not suppress the HU sensitivity of rad3ts cells at 32°C (data not shown). Like cid11Δ (null) mutants, cid13Δ and cid13Δ cid11Δ double mutants showed no obvious growth or morphology phenotypes (data not shown). However, unlike cid11Δ, cid13Δ strains were hypersensitive to prolonged exposure to HU (Fig. 3F). cid13Δ cid11Δ double mutants were as sensitive to HU as single cid13Δ mutants. None of the single or double mutants exhibited sensitivity to UV or gamma irradiation (data not shown). Significantly, deletion of cid13 increased the HU sensitivity of rad3ts and rad3Δ mutants (Fig. 3F).

These data suggest that cid13 acts independently of rad3 to promote survival after exposure to HU. Several explanations for this are possible. First, cid13 might control a rad3-independent checkpoint response. Alternatively, cid13 could improve the efficiency of DNA replication or repair processes, or could influence the toxicity of HU either directly or indirectly. We assayed the appearance of unscheduled mitotic (“cut”) cells after HU treatment of cid13Δ, rad3Δ, and rad3ts cells (with or without cid13oe). No significant effects of cid13 on the S–M checkpoint were seen in any case (data not shown). Although we cannot exclude a direct role for cid13 in DNA repair or replication, we did not observe changes in the rate of DNA replication in cid13Δ cells by flow cytometry of cells synchronized by centrifugal elutriation or observe any UV, methyl methane sulphonate, or ionizing radiation sensitivity (data not shown). We infer that cid13 functions to affect dNTP metabolism in such a way as to maintain dNTP pools.

Cid1 and Cid13 Are Cytoplasmic Proteins.

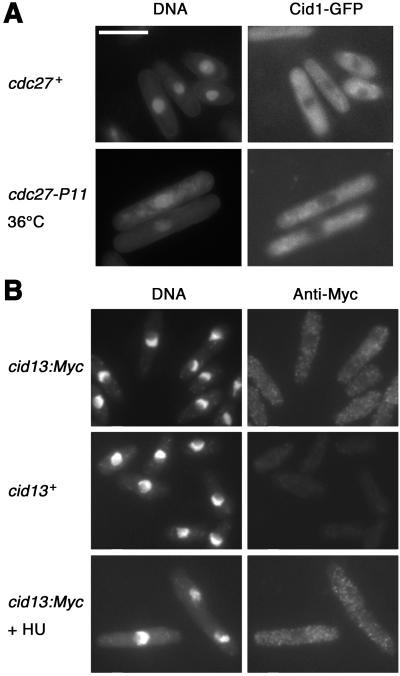

To characterize the physiological roles of Cid1 and Cid13 in more detail, we fused sequences encoding GFP, Myc, or hemagglutinin (HA) epitopes to the 3′ ends of the cid1 and cid13 ORFs at their normal chromosomal loci. cid1:GFP and cid1:HA strains were not sensitive to the combination of HU and caffeine, and cid13:Myc was not sensitive to HU, indicating that the tags do not affect Cid1 or Cid13 function (data not shown). Surprisingly, given the poly(A) polymerase activity of Cid1, Cid1–GFP, Cid1–HA, and Cid13-myc appeared exclusively cytoplasmic in exponentially growing cells (Fig. 4 and data not shown). Because Cid1 is required for checkpoint integrity when Pol δ or ɛ is inactivated and Cid13 is required for HU resistance, it seemed possible that under these stress conditions, Cid1 or Cid13 might enter the nucleus. Pol δ was inactivated in a temperature-sensitive cdc27-P11 strain by shifting to the restrictive temperature (36°C) for 4 h. However, the localization of Cid1-GFP was not altered under these conditions (Fig. 4A). Similarly, Cid13 localization was unaffected by incubation in HU (Fig. 4B).

Fig 4.

Cid1 and Cid13 are cytoplasmic proteins. (A) Fluorescence micrographs of living cid1-GFP cells stained briefly with Hoechst 33258 to reveal DNA (Left) and GFP fluorescence (Right). (Upper) cid1-GFP (cdc27+) cells grown at 32°C. (Lower) cid1-GFP cdc27-P11 cells shifted to 36°C for 4 h. (B) Micrographs of fixed wild-type (cid13+; negative control) and cid13:Myc cells, as indicated, processed for anti-Myc immunofluorescence (Right) and stained with DAPI to reveal DNA (Left). The cells in the lower panels were exposed to 20 mM HU for 3 h before fixation. (Scale bar: 10 μm.)

Physiological Substrates of Cid1 and Cid13.

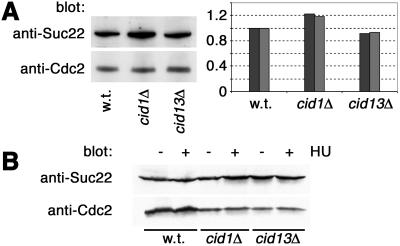

We identified the suc22 gene in the same screen through which we isolated cid13. We therefore considered the possibility that Cid13 might positively regulate Suc22. Immunoblotting of whole-cell lysates indicated that constitutive Suc22 levels were not significantly altered on deletion of either cid13 or cid1 (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, no significant change in Suc22 level was seen in wild-type, cid1Δ, or cid13Δ cells after exposure to HU (Fig. 5B). We conclude that the HU sensitivity of cid13Δ cells is not attributable to a failure to up-regulate Suc22 protein levels.

Fig 5.

Expression of Suc22 does not depend on Cid1 or Cid13. (A) Suc22 protein levels in whole-cell lysates from wild-type (w.t.), cid1Δ, and cid13Δ strains were estimated by immunoblotting with a polyclonal anti-Suc22 antibody (Upper Left). Protein loading was controlled by reprobing the same filter with an anti-Cdc2 antibody. Suc22 levels in two independent experiments were quantified by densitometry and expressed graphically (Right) after normalizing for Cdc2 levels. (B) Suc22 and Cdc2 immunoblotting was performed as in A from parallel cultures that had been exposed (+) or not (−) to 10 mM HU for 4 h at 30°C.

Discussion

Cid1 is representative of a class of cytoplasmic proteins with poly(A) polymerase activity. The canonical poly(A) polymerase is responsible for bulk mRNA polyadenylation in the nucleus following the site-specific cleavage of primary PolII transcripts (17). Poly(A) tail length is associated with stability of the mRNA and efficient translation after export to the cytoplasm, as the poly(A) binding protein is an important component of the translation preinitiation complex (18). The cytoplasmic location of Cid1 and Cid13 suggests that their biological functions are distinct from that of nuclear poly(A) polymerase. The distinctive phenotypes of the respective deletion mutants, and the apparent selectivity of Cid1 for particular RNA substrates in vitro (Fig. 2D), lead us to suggest that Cid1 and Cid13 act to extend the poly(A) tails of distinct subsets of cytoplasmic mRNAs. Poly(A) tail extension would be predicted to increase the levels of the corresponding protein products by promoting mRNA stability and/or translation efficiency. In support of this interpretation, during the preparation of this manuscript Saitoh et al. (19) reported that partially purified Cid13 also possessed poly(A) polymerase activity. Other members of the immediate Cid1 family such as Cid11 presumably have significantly different substrate preferences. Our findings also differentiate Cid1 and Cid13 from their closest relative in S. cerevisiae, Trf4, which is nuclear and was reported to function as a Pol (4, 20). Multiple Cid1/Cid13-related proteins are found in distantly related eukaryotes including Caenorhabditis elegans, plants, and humans. One of these C. elegans proteins has recently been identified independently as a cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase (Liaoteng Wang and Judith Kimble, personal communication). Furthermore, at least one of the human Cid1-like proteins is constitutively cytoplasmic (Soyoung Min and C.J.N., unpublished data). Unlike the canonical poly(A) polymerase, none of the Cid proteins contains a conventional RNA recognition motif. Our in vitro data suggest that Cid1 can nonetheless interact productively with RNA in the absence of such a motif. RNA binding partner proteins may act to modulate the efficiency or specificity of such interactions in vivo. This might explain the relatively low specific activity of our recombinant Cid1 in comparison with S. cerevisiae poly(A) polymerase (Fig. 2A). Alternatively, the low specific activity might indicate that only a small proportion of the recombinant protein is properly folded.

Cid1 and Cid13 can each partially suppress the HU sensitivity of rad3 mutants, but the underlying mechanisms appear to differ. cid13Δ cells were hypersensitive to long-term exposure to HU (Fig. 3F) but were fully proficient for the S–M checkpoint and not sensitive to short-term HU exposure (data not shown). In contrast, cid1D cells were not unusually sensitive to HU, except in the presence of caffeine (5). Suppression of rad3ts HU sensitivity by overexpression of either suc22 or cid13 did not depend on residual rad3 function (Fig. 3 B and D and data not shown), and deletion of cid13 increased the HU sensitivity of rad3ts and rad3Δ cells (Fig. 3F). These observations suggest that cid13, like suc22, suppresses the HU sensitivity by a bypass mechanism and that cid13 and rad3 do not function in the same pathway. In the case of overexpression of Suc22, suppression of HU sensitivity presumably reflects restoration of dNTP pools. Cid13 was recently reported to contribute to the maintenance of steady-state dNTP pools and to promote suc22 mRNA polyadenylation and stability after exposure to HU (19). Extension of poly(A) tail length would be expected to promote translation of suc22 mRNA, but our data show that total Suc22 protein levels are not influenced by cid13 function, either in the presence or absence of HU (Fig. 5). It is a formal possibility that Cid13-mediated polyadenylation in the cytoplasm controls suc22 mRNA translation in some way that is not reflected in a change in total Suc22 protein level. Alternatively, other targets of Cid13 may be more important for the maintenance of dNTP pools. Cid1 also appears not to regulate Suc22, and the mRNA targets that explain the specific checkpoint defects of the cid1Δ strain await identification.

Cytoplasmic polyadenylation of maternal mRNA has been known for some time to be an important regulatory mechanism in early animal development (21). Our demonstration of Cid1 poly(A) polymerase activity, together with the evolutionary conservation of the Cid1 gene family, supports the idea that cytoplasmic polyadenylation might be of more general importance, both in unicellular and in more complex eukaryotes. Cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase in early Xenopus embryos is maximally active in mitosis, when the nuclear enzyme is inhibited by phosphorylation (22). This suggests that the polymerases responsible are fundamentally distinct, but the cytoplasmic activity has not yet been characterized in detail. Signal-induced cytoplasmic polyadenylation has also been described in neurons, although here, too, the polymerase responsible has not yet been identified (23). It will be interesting to determine whether Cid1-related proteins account for any of these cytoplasmic activities and if such polymerases are subject to stimulus-specific regulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tony Willis for N-terminal sequencing, Len Wu for help with protein purification, Judith Kimble for discussing results before publication, Nick Proudfoot for advice, and Ian Hickson for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by Cancer Research UK, the Medical Research Council, the Association for International Cancer Research, and the Association of Commonwealth Universities (Scholarship to R.L.R.).

Abbreviations

HU, hydroxyurea

Pol, DNA polymerase

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the SwissProt database (accession no. Q9UT49).

References

- 1.Bentley N. J., Holtzman, D. A., Flaggs, G., Keegan, K. S., DeMaggio, A., Ford, J. C., Hoekstra, M. & Carr, A. M. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 6641-6651. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melo J. & Toczyski, D. (2002) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 237-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uhlmann F. (2001) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 754-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z., Castano, I. B., De Las Penas, A., Adams, C. & Christman, M. F. (2000) Science 289, 774-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang S. W., Toda, T., MacCallum, R., Harris, A. L. & Norbury, C. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 3234-3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang S. W., Norbury, C., Harris, A. L. & Toda, T. (1999) J. Cell Sci. 112, 927-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aravind L. & Koonin, E. V. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 1609-1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawaya M. R., Pelletier, H., Kumar, A., Wilson, S. H. & Kraut, J. (1994) Science 264, 1930-1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moreno S., Klar, A. & Nurse, P. (1991) Methods Enzymol. 194, 795-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinho R. G., Lindsay, H. D., Flaggs, G., DeMaggio, A. J., Hoekstra, M. F., Carr, A. M. & Bentley, N. J. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 7239-7249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bahler J., Wu, J. Q., Longtine, M. S., Shah, N. G., McKenzie, A., III, Steever, A. B., Wach, A., Philippsen, P. & Pringle, J. R. (1998) Yeast 14, 943-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindsay H. D., Griffiths, D. J., Edwards, R. J., Christensen, P. U., Murray, J. M., Osman, F., Walworth, N. & Carr, A. M. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 382-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagan I. M. & Hyams, J. S. (1988) J. Cell Sci. 89, 343-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karow J. K., Chakraverty, R. K. & Hickson, I. D. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 30611-30614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wahle E., Martin, G., Schiltz, E. & Keller, W. (1991) EMBO J. 10, 4251-4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin G. & Keller, W. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 2593-2603. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proudfoot N. J., Furger, A. & Dye, M. J. (2002) Cell 108, 501-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pestova T. V., Kolupaeva, V. G., Lomakin, I. B., Pilipenko, E. V., Shatsky, I. N., Agol, V. I. & Hellen, C. U. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 7029-7036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saitoh S., Chabes, A., McDonald, W. H., Thelander, L., Yates, J. R. & Russell, P. (2002) Cell 109, 563-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walowsky C., Fitzhugh, D. J., Castano, I. B., Ju, J. Y., Levin, N. A. & Christman, M. F. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 7302-7308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richter J. D. (1999) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63, 446-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groisman I., Jung, M. Y., Sarkissian, M., Cao, Q. & Richter, J. D. (2002) Cell 109, 473-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Y. S., Jung, M. Y., Sarkissian, M. & Richter, J. D. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 2139-2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]