Abstract

Complex chromosome aberrations are characteristically induced after exposure to low doses of densely ionizing radiation, but little is understood about their formation. To address this issue, we irradiated human peripheral blood lymphocytes in vitro with 0.5 Gy densely ionizing α-particles (mean of 1 α-particle/cell) and analyzed the chromosome aberrations produced by using 24-color multiplex fluorescence in situ hybridization (M-FISH). Our data suggest that complex formation is a consequence of direct nuclear α-particle traversal and show that the likely product of illegitimate repair of damage from a single α-particle is a single complex exchange. From an assessment of the “cycle structure” of each complex exchange we predict α-particle-induced damage to be repaired at specific localized sites, and complexes to be formed as cumulative products of this repair.

Ionizing radiation is extremely effective in producing chromosomal aberrations. Practically, this enables their induction to be applied in the study of assessing cancer risks and other public health questions associated with the environment, including as specific biomarkers of exposure (1, 2), or from occupational (3) and therapy-related exposures (4). Double-strand breaks (dsb) of varying complexity are an important class of damage induced after exposure to ionizing radiation, and chromosome aberrations are formed as one consequence of the cellular processes initiated for their repair (5–8). However, the dynamics of aberration formation are not known. One approach that allows mechanistic questions to be addressed is to characterize the different types of chromosome aberration induced after exposure to specific qualities of ionizing radiation. Each radiation-induced damaged cell will contain a unique rearrangement, but it is expected that the qualitative “form” of the induced rearrangement will reflect the initial spectrum of dsb damage induced. Assuming that the damage induced is a direct consequence of the radiation track interacting with the DNA, then the structure of the radiation track should influence the type of chromosome aberration observed (2, 9, 10). Collectively from this, predictions can be made as to how damaged chromatin “ends” associate before their ultimate misrepair.

The range and dimensions of a five-million-electrovolt (MeV; 1 eV = 1.602 × 10−19 J) α-particle, like that emitted from radon in the environment, are typically short (40 μm) and of limited maximum radial spread (0.1 μm), with ≈90% of energy deposition within 10 nm. Consequently, high-linear energy transfer (LET) α-particles are only capable of intersecting a very small fraction of the total cell volume, which, if by chance is intersected, will almost never be intersected by another track (10). These particles are, however, extremely effective in producing a high density of localized molecular lesions because of the deposition of large clusters of energy (400–800 eV) along the entire length of the track (≈25–50 such clusters in nucleosomes per cell per α-track). These energy depositions are capable of inducing complex local damage to the chromatin (1 or more dsb, base damage, and other associated breaks) that is known to repair less efficiently than simple dsb (11). By comparison, cellular exposure to low-LET radiation, such as x-rays, results in an energy distribution that is spread more uniformly through the cell with more minor clustering. So, the spatial patterns of energy distribution by high- and low-LET radiations are characteristically different over cellular, subcellular, and macromolecular distances (12).

Complex chromosome aberrations (defined as involving three or more breaks in two or more chromosomes) (13) are known to be characteristically induced after exposure to low doses of high-LET radiation (1, 14–18). To date, the full cytogenetic complexity of these aberrations has not been revealed because standard fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) techniques are limited in the number of chromosomes that can be “painted.” The development of multiplex-FISH (M-FISH) (19), however, has changed this because it enables the discrimination of all of the human chromosomes by means of the combinatorial labeling of individual chromosomes with spectrally distinct fluorophores. With the exception of interchanges between homologues, it allows all of the chromosomes participating in each aberration, within any cell, to be observed, and the relationship between different aberrant chromosomes to be determined (20). We have used this technique to examine the cellular-wide damage and complexity of induced aberrations after exposure to a low dose of high-LET α-particles (1), using a relatively high dose of low-LET x-rays as a reference, with the aim of addressing the question of how α-particle-induced complex chromosome aberrations are formed.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and in Vitro Irradiation.

Whole blood was collected from three healthy volunteers and separated to isolate the peripheral blood lymphocyte (PBL) fraction using vacutainer-CPT mononuclear cell preparation tubes (Becton Dickinson). The cells were plated as a monolayer and irradiated in G0 with either 0.5 Gy α-particles (3.26 MeV) or 3 Gy x-rays (250 kV) (1). The α-particle dose was chosen to give on average 1 α-particle traversal per cell and the x-ray dose was selected at a much higher level to ensure that sufficient complex aberrations were induced for comparative purposes (21). After irradiation, T lymphocytes were stimulated to divide and harvested to obtain first-division metaphase chromosomes as described (1).

M-FISH.

Fresh slides of metaphase chromosomes were hardened (3:1 methanol/acetic acid for 1 h, dehydrated, baked at 65°C for 20 min, then 10 min in acetone) and pretreated with RNase (100 μg/ml) at 37°C for 1 h. After washing in 2× SSC and PBS, the cells were treated with 0.65M KCL for 10 min at room temperature, washed, dehydrated, and further treated with 0.16 μg/ml proteinase K in Tris⋅HCl/CaCl2 for 10–30 min at 37°C. Finally, the cells were washed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 5–10 min, washed again, and dehydrated. For hybridization, cells were denatured in 70% formamide/2× SSC at 72°C for 3 min and dehydrated for 1 min each in 70/90/100% ethanol. As this was happening, the commercially available 24-color paint mixture SpectraVision assay (Vysis Inc., Downers Grove, IL), was denatured (73°C for 6 min). Cells were left to hybridize for 36–48 h at 37°C before being washed in 0.4× SSC/0.3% Igepal (Sigma) (71°C for 1.5 min) and 2× SSC/0.1% Igepal (room temperature for 10 s). Cells were counterstained by using DAPI III (42 ng/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole in antifade mounting solution), sealed, and stored in the dark at −20°C.

Metaphase chromosomes were visualized by using a 6-position Olympus BX51 fluorescent microscope containing individual filter sets for each component fluor of the SpectraVision probe mixture plus DAPI (Spectrum Gold, Spectrum Far-red, Spectrum Aqua, Spectrum Red, and Spectrum Green). Digital images were captured for M-FISH with a charged-coupled device (CCD) camera (Photometrics Sensys CCD) coupled to and driven by Genus (Applied Imaging, Newcastle upon Tyne, U.K.). In the first instance, cells were karyotyped and analyzed by enhanced DAPI banding. Detailed paint analysis was then performed by assessing paint coverage for each individual fluor down the length of each individual chromosome, using both the raw and processed images for each fluor channel. A cell was classified as being apparently normal if all 46 chromosomes were observed by this process, and subsequently confirmed by the Genus M-FISH assignment to have their appropriate combinatorial paint composition down their entire length.

Chromosome Aberration Classification.

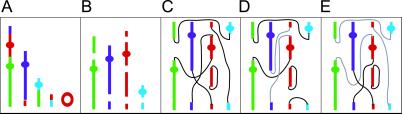

Exchange aberrations involving three or more breaks in two or more chromosomes were classified as complex and assigned the most conservative C/A/B (minimum number of chromosomes/arms/breaks involved) (13). To do this, the relative breakpoint positions of the visible color junctions (Fig. 1A) were estimated by using enhanced DAPI banding and an assessment of arm ratio and size of rearranged material. We used colored markers to produce a cartoon detailing the position of these “reactive breaks” before their complex interaction (Fig. 1B). Then, assuming each breakpoint produces two “free-ends,” the observed complex was reconstructed by using this cartoon until all of the free-ends were “closed” (Fig. 1 C–E). In other words, all of the break-ends have a partner and all rearranged chromosomes have telomeric ends, unless they are ring chromosomes; for detailed discussion, see ref. 22. When more than one option to achieve completeness was possible, the rearrangement that produced the minimum C/A/B was used. Missing or unresolvable elements required to achieve completeness were easily identified by this procedure and, as a consequence, could be assumed (23).

Fig 1.

(A) Cartoon of a “complete” α-particle-induced complex given a C/A/B classification of 4/5/6. (B) Estimated position of breakpoints on each damaged chromosome. (C–E) Reconstruction of the chromosome break-ends to produce the observed complex. Theoretically, this complex could be produced by the proximate interaction of all free-ends (C), thus, if no other rejoining solution were possible, this complex would be classified as a “nonreducible complex of size c6.” However, as shown in D and E, this complex could also be reduced into two different sequential exchanges of sizes c2+c4 (D) and c3+c3 (E). No other combination of cycles that produced the observed complex were theoretically possible, consequently, the “obligate cycle structure” (22) was scored as c3+c3 because this represented the least complex of all theoretical cycle sizes.

Complex exchanges were thus grouped as complete, unresolved incomplete, or true incomplete exchanges. Each complex exchange was then categorized as a single event and independent of any other complex, simple (maximum of two breaks in two chromosomes) or break (chromosome breaks not involving additional chromosomes) observed in the same cell.

Sequential Exchange Complexes (SEC).

A SEC is defined as a complex exchange that can be reduced into smaller independent exchange events (cycles) that are temporally or spatially separated from one another, but where each event has a common link (24) (for detailed discussion, see ref. 22). Characterized by a nomenclature system introduced by Sachs et al. (25), each cycle gives information on the minimum number of interactions (and therefore free-ends) that were proximate, and, as a consequence, the minimum number of chromatin strands that misrepaired within the repair site volume.

For many complex aberrations, there may be a number of possible “rejoining cycles” that are theoretically capable of reconstructing the observed complex (for detailed discussion, see ref. 22). Therefore, in an effort to standardize this data, we assigned the most conservative, or obligate cycle structure (22), to each complex (Fig. 1E). Because mechanistic interpretations were performed by using these obligate cycle structures, it should be highlighted that the obligate cycle structures may not represent the actual route of formation of each complex.

Therefore, this classification identifies those complexes that can be reduced into SEC, and the recorded obligate cycle structure represents the minimum degree of complexity required to form each complex exchange.

Simulation.

This simulation, developed to estimate the number of chromosomes crossed by an α-particle track in a G0 cell nucleus, relies on the observation that any chord passing through a sphere lies on an equatorial plane. By modeling the number, areas, and shapes of the intersections of chromosome domains with representative nuclear equatorial planes (NEPs), and with appropriate weighting, a reasonable representation of the interaction of α-particles with spherical nuclei can be obtained. The simulation uses no adjustable parameters and it assumes only that the cell nucleus is spherical, valid for human lymphocytes, and that there are 46 equally sized chromosome domains closely packed within the nucleus. The method could be adapted to any nucleus shape with axial symmetry, but is limited to radiations producing linear and narrow tracks.

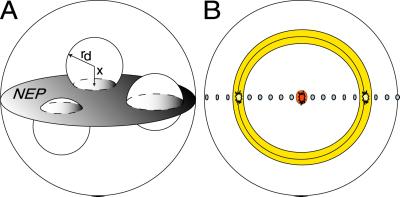

If a chromosome domain is assumed to be spherical and it intersects randomly with a NEP (Fig. 2A), its area of intersection can be assumed to be π(r2 − x2), where r is the domain radius and x is chosen from a uniform random distribution between −r and r. Domain areas were sequentially subtracted from the NEP area until the calculated domain area was larger than the residual area of the NEP. The last domain area was then taken as that residual area. By repeating this process 200 times, we obtained information on the number and areas of chromosome domains intersecting NEPs. The number of chromosome domains intersecting with NEPs is shown in (Fig. 3A).

Fig 2.

A model was developed to predict the number of chromosome domains crossed by the traversal of a α-particle through the cell nucleus. (A) Calculation of number and size of domain intersections in a NEP. (B) Top view of NEP crossed by 19 parallel chords.

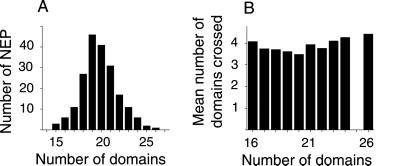

Fig 3.

(A) Distribution of the number of chromosome domains that intersect with a NEP. (B) The mean numbers of domains that are crossed by a single α-particle track in NEPs that are intersected by different numbers of domains.

Representative NEPs from this distribution were constructed with domain areas drawn by hand as circular as possible while ensuring efficient packing (e.g., Fig. 4A). Nineteen parallel chords were then placed uniformly across each NEP (Fig. 2B), and the number of domains crossed by each chord was recorded. By weighting the number of domains crossed by a chord, by the likelihood that a chord of that length will occur through a spherical nucleus (proportional to area of the circular element, e.g., illustrated for two areas in Fig. 2B), a distribution of the number of domains a chord/track will cross was obtained. The means of the distributions are shown in Fig. 3B. By weighting these distributions with the likelihood that they will occur (Fig. 3A), the overall distribution of the number of domains α-particles will cross, was obtained (Fig. 5A). The distribution after adjustment for involvement of homologous chromosomes is also shown in Fig. 5A.

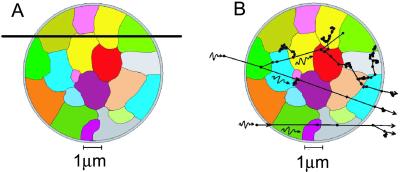

Fig 4.

Transverse section, at maximum diameter, of modeled PBL cell nucleus showing individual chromosome domains being crossed by an α-particle (A) and electron tracks from two x-ray interactions (B).

Fig 5.

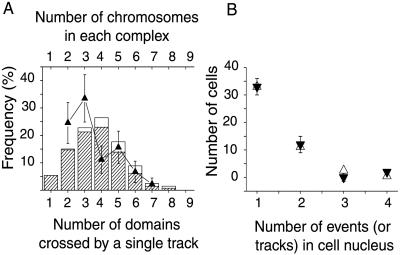

(A) Distribution of the number of domains predicted to be crossed by a single α-track, compared with the distribution of observed number of chromosomes in each complex. When all α-particle-induced complexes from group A in Table 1 were used, normalized to model data involving 2 or more domains, a similar trend was seen between the observed number of chromosomes involved in each complex (▴) and that predicted from the model (hashed bar and open bar; open bar being the subset that could be attributed to a track crossing homologous chromosomes). Error bars represent the standard error of the value (assuming a Poisson distribution). (B) The number of independent events (simple, complex, or break only) in each damaged cell (▾) was compared with the expected Poisson distribution of nuclei “hit” by 1, 2, 3, or 4 α-particles (▵), normalized to the single-event cells. Broad-beam irradiation of 0.5 Gy delivers a mean of 1 α-particle per cell with a Poisson distribution of particle hits of 51:34:15 for 0:1:>1 particles/nucleus respectively (1). Error bars represent the standard error of the value.

Results and Discussion

Quality of Aberration Induced by Nuclear Traversal of One α-Particle.

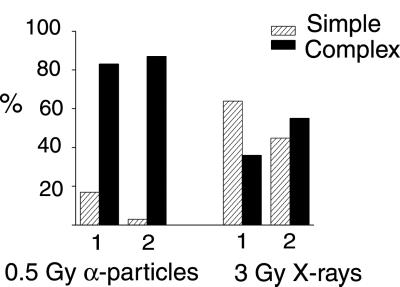

Under the experimental conditions used here, each human PBL irradiated with 0.5 Gy α-particles and 3 Gy x-rays, would receive on average 1 and ≈700 tracks, respectively, with the x-rays causing about 6-fold more ionisations (Fig. 4). Interestingly though, we observed no difference in the total cellular damage, based on the mean number of damaged chromosomes (C) and breaks (B) involved, between the two radiation qualities (low-dose α-particles: C = 5.37 ± 0.33, B = 7.36 ± 0.47 and high-dose x-rays: C = 5.29 ± 0.46, B = 6.90 ± 0.6). Instead, the spatial differences in deposition of energy were reflected by the quality of aberration classified. Specifically, 83% of total exchanges detected were complex (three or more breaks in two or more chromosomes) after α-particles (Fig. 6). This compares with only 36% after the high dose of x-rays, and is consistent with the observations of Loucas and Cornforth (23). More striking, 87% of all cells observed to be damaged after α-irradiation contained at least 1 fully definable complex rearrangement (Fig. 6), suggesting that the damage from α-particle traversal nearly always repairs as a complex exchange event. In addition, the complexity of each complex was greater and the mean number of independent exchanges/cell fewer, after 0.5 Gy α-particles when compared with the relatively high dose of 3 Gy x-rays. Therefore, radiation track structure does determine the “forms,” as well as the total yield, of aberration induced (10, 11, 26), supporting the view that spatial proximity between induced dsb influences the chance of their interaction (27).

Fig 6.

The proportion of simple and complex aberrations induced after exposure to 0.5 Gy α-particles and 3 Gy x-rays are displayed in two ways: as the number of simple or complex exchanges expressed as a percentage of the “total exchanges” (1), and as the number of cells containing only simple exchanges or at least one complex exchange, expressed as a percentage of “all damaged cells” (2). Thirty-two percent of cells exposed to α-particles were damaged, and 87% of these contained at least one fully definable complex. Considering the cells that did not contain one fully definable complex, we found 1 cell with an exchange classed as a simple, but that contained a “hidden” complex event, whereas the remaining 3 cells each showed a single broken chromosome. Such breaks are also observed in sham-irradiated cells and are believed to arise as a consequence of mechanical damage, but they could also be considered as end products of unrejoined damage to a single chromosome domain. Fully 91% of cells exposed to 3 Gy x-rays were visibly damaged; all contained exchanges.

We used a coirradiation system, developed in our unit (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org) to assess whether complex aberrations might also arise in cells that had not been directly traversed by a α-particle track. Our data show that complexes were induced only in cells in the irradiated subpopulation, confirming that their induction depends on α-particle nuclear traversal (see supporting information, which is published on the PNAS web site).

We next asked whether each complex was the end-product of the interaction of damage caused by more than 1 α-particle traversal. To do this, we independently developed a model that predicted the distribution of the number of chromosome domains that would be traversed by an α-particle, given random trajectories through the G0 cell nucleus (Figs. 2, 3, and 5). Comparison of this theoretical distribution with the distribution of the number of chromosomes experimentally observed in each complex suggests that the damage induced by the nuclear traversal of a single α-particle results in the formation of a single complex exchange (Fig. 5A). Considering this argument with the fact that a number of PBL will be traversed by more than 1 α-particle, a statistical consequence of broad-beam exposure, we categorized each aberration classified as either a simple, complex, or break, as an independent event. From this, we can show a similar trend between the Poisson distribution of cells hit by 1, 2, 3, or 4 α-particles and the number of independent events observed in each damaged cell (Fig. 5B). Consequently, we propose that the damage arising from 1 α-particle will normally result in 1 complex event. If so, then this is relevant for the study of single-track or low-dose cellular effects and it could also have major implications for epidemiological studies assessing public health risks from the exposure to domestic radon. It is also relevant to note that this predominant induction of complex chromosome aberrations throughout a population of PBL after exposure to an environmentally relevant dose of α-particles, strengthens the authors' proposal that complexes per se could be exploited as biomarkers for the identification of highly exposed individuals (1).

Formation of α-Particle-Induced Complex Aberrations.

It is generally accepted that radiation-induced dsb formed in G0/G1 are repaired by the nonhomologous end-joining pathway (28); the role of homologous recombination and the recruitment of homologous chromosomes (29) in complex aberration formation is not known. Considering α-particle-induced complexes, we found that 13 of 56 damaged cells had at least one complex that involved at least 1 homologous chromosome pair (Table 1, group C) and overall, ≈1/3 of all damaged cells contained at least one damaged pair (Table 1, groups B and C). To determine whether this represented homologous pair nonrandom involvement in these α-particle-induced complexes, a Monte Carlo simulation of one million tests was performed. The results show that the observed level of homologous pair involvement in complex exchanges did not represent a deviation from that expected by a random breakage and reunion model and is consistent with the prediction that a significant proportion of exchanges will involve both homologues (22). Damage to homologous chromosome pairs can, however, limit their discrimination into separate independent complex events, with the result that it is not possible to determine whether those particularly complex events are products of damage caused by the traversal of >1 α-particle (Table 1, groups B and C). Consequently, the data were subdivided into groups A-C in Table 1, with all analyses performed by using only the data in group A (damaged metaphases not involving two damaged homologues).

Table 1.

Complexity of all α-particle-induced complex exchanges

| Complexity | Group A, no homologous pairs | Group B, separate-event homologous pairs | Group C, same-event homologous pairs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of chromosomes | No. of breaks | Total | Obligate cycle structure | Total | Obligate cycle structure | Total | Obligate cycle structure |

| 2 | 3 | 5 | c3 | − | − | 2 | c3 |

| 4 | 4 | c2+c2/c4 | − | − | − | − | |

| 5 | 2 | c2+c3/c5 | − | − | − | − | |

| 3 | 3 | 8 | c3 | − | − | − | − |

| 4 | 3 | c2+c2/c4 | 1 | c2+c2 | 2 | c2+c2/c4 | |

| 5 | 1 | c5 | 1 | c2+c3 | − | − | |

| 6 | 1 | c2+c4 | − | − | − | − | |

| 7 | 1 | c2+c2+c3 | − | − | − | − | |

| 9 | 1 | c2+c3+c4 | − | − | − | − | |

| 4 | 4 | 1 | c4 | 1 | c4 | 2 | c4 |

| 5 | 2 | c2+c3/c5 | 1 | c5 | − | − | |

| 6 | 2 | c3+c3/c6 | 1 | c3+c3 | 1 | c6 | |

| 7 | − | − | 1 | c2+c2+c3 | − | − | |

| 5 | 5 | − | − | − | − | 2 | c5 |

| 6 | 2 | c6 | − | − | − | − | |

| 7 | 2 | c2+c2+c3/c3+c4 | 1 | c7 | 2 | c2+c2+c3/c7 | |

| 8 | 2 | c2+c3+c3/c2+c6 | − | − | − | − | |

| 11 | 1 | c2+c2+c3+c4 | − | − | − | − | |

| 6 | 9 | − | − | 1 | c3+c3+c3 | − | − |

| 10 | 2 | c2+c3+c5/c2+c8 | − | − | − | − | |

| 11 | − | − | − | − | 1 | c11 | |

| 12 | 1 | c2+c3+c3+c4 | − | − | − | − | |

| 7 | 9 | − | − | − | − | 1 | c2+c2+c5 |

| 10 | 1 | c2+c3+c5 | − | − | − | − | |

| 11 | − | − | − | − | 1 | c11 | |

| 8 | 8 | − | − | − | − | 1 | c3+c5 |

| 9 | 11 | − | − | − | − | 1 | c4+c7 |

| 10 | 13 | − | − | − | − | 1 | c13 |

Complexity of each independent complex event was assessed according to the minimum number of chromosomes and breaks involved. To prevent ambiguity, we have separated all the data into 3 different groups (A, B, and C). The rationale for this relates to the difficulties faced when classifying complexes when both chromosome homologues are damaged in a cell, illustrated by the finding that only 41% of the complexes in group A were classed as unresolved–incomplete exchanges, whereas 88% and 76% were similarly classed from groups B and C. Thus, group A details only those complexes found in cells where no homologous pair was damaged, group B details all complexes found in cells that had at least one homologous pair damaged but which were classed as separate events, and group C details all those remaining complexes that had at least one homologous pair involved in the same event. To address potential mechanistic routes of complex formation, we derived every possible theoretical rejoining cycle, based on breakage and reunion, that was capable of resulting in the observed complex. The most conservative or obligate rejoining cycle structure (22) is noted for each complex, the ratio for each cycle in all those showing two different cycle paths noted is 1:1, except

, which is 2:1. Considering group A, 23 of 42 complexes were nonreducible (range c2–c6), implying that repair of up to 12 free-ends occurred in the same irreducible interaction, localized in space and possibly time. Two of 42 complexes were SECs (c2+c2 and c2+c6), with only one theoretical rejoining path, and 17 of 42 were SECs that had multiple theoretically possible rejoining paths.

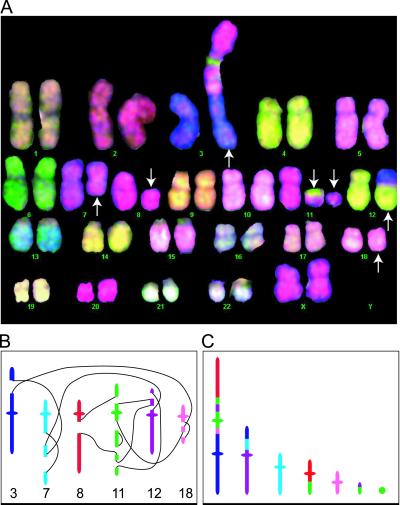

Based on our theoretical model (Fig. 5A), we predict that the nuclear traversal of a single α-particle will intersect with between 1 and 8 different chromosome domains and therefore, the complexity of any observed α-particle-induced complex should not involve more than 8 different chromosomes. Our experimental data show complexity to range from involving 2 chromosomes and 3 breaks to 7 chromosomes and 10 breaks with the average involving 4 different chromosomes and 6 different breaks (Table 1, group A). Chromosomes are known to occupy discrete territories or domains during interphase (30), and it is expected that there is limited intermingling of chromatin strands, yet the complexity of a α-particle-induced complex suggests multiple damaged chromatin strands must associate. Therefore, by what mechanism do damaged chromatin strands from multiple domains repair, allowing the resulting product to be visible as a single complex event? To address this, we derived every possible theoretical rejoining path of all damaged chromosome ends that could have resulted in the generation of each α-particle-induced complex that was visualized by M-FISH (see Materials and Methods and Fig. 1, and further detailed in refs. 22, 23, and 25). Specifically, we asked whether a complex could be the end product of a number of smaller events that occurred at different sites involving common chromosomes.

When we used the complexes from group A in Table 1 only, we found 23 of 42 complexes were of the nonreducible complex type, whereas 19 of 42 could be reduced into smaller SEC (see Materials and Methods). Interestingly, 2 of 19 could only be reconstructed into the observed complex as SECs, i.e., it was not theoretically possible to produce the complex as one large nonreducible cycle. For the remaining SEC, each complex could be reconstructed either as one large cycle or by means of the potentially numerous combinations of theoretically possible cycles.

The cycle sizes necessary to result in the formation of the nonreducible complexes ranged from cycle order 2 (c2) to c6, implying that up to 6 different breaks (12 free-ends) were illegitimately repaired within the same nuclear area. It is known that densely ionizing α-particles are capable of inducing multiple sites of DNA damage in a localized volume (26), thus key to the formation of these cycles are questions that relate to the organization of chromatin at the time of damage (31, 32). In other words, are breaks induced in chromatin loops of preexisting functional associations, or do damaged ends mobilize to form “chromatin aggregates” that function as “repair centers”? (30, 33–35). Comprehensive statistical analysis of our data (not shown) show the distribution of breakpoints for each chromosome to be essentially random, with no evidence of association between chromosomes involved in each complex (analysis based on the group A in Table 1). Thus, we could not relate chromosome involvement within each complex to chromosome territory organization in interphase. Recognizing the infinite number of possible trajectories of a α-particle track through a cell nucleus, and that both repair centers and preexisting associations localize within interchromatin spaces, we propose that our data are more consistent with the moving together of chromatin-ends after damage. It seems unlikely that all breaks occurred at one site, based on considering the dimensions of the α-particle track and the number of different chromosomes involved in each complex: this would require chromatin associations to occur at high density, however dynamic, and typically to involve many different chromatin loops. Instead, we predict that limited directed movement to the nearest local repair center could account for proximity effects (27) and, also, the observed number of different chromatin strands involved in each cycle. To elaborate on this latter point, 19 of 42 of the α-particle-induced complexes were reducible into SECs; Table 1 group A shows the obligate SEC for each. This obligate structure represents the minimum number of chromatin break-ends in each cycle that would be required to form that particular complex, but is not necessarily the most likely (Fig. 7) (22). For many SECs, theory predicts other possible combinations of rejoining cycles, each of which involve many more chromatin strands in each cycle and that, by definition, would be required to be in the same space for repair. Therefore, it cannot be excluded from these data that the complexity of each α-particle-induced complex is caused by the recruitment of undamaged DNA (36), consistent with Chadwick and Leenhouts (37) theory that damaged and undamaged DNA interact to form exchanges.

Fig 7.

(A) M-FISH karyotype showing an α-particle-induced complex involving chromosomes 3, 7, 8, 11, 12, and 18 (arrows) and classified as 6/7/12. (B) Detail of the chromosomes involved and the relative breakpoint positions. Based on the breakpoints assigned, we can predict completeness of the exchange by assuming either (i) chromosomes 7 and 18 have rejoined with themselves (as shown in C), or (ii) chromosomes 7 and 18 have exchanged with 18qter and 7qter, respectively, but below the limit of resolution (not shown). All other participating chromosome ends of the complex are accounted for, but further assumptions for rejoining are required because of the inability to discriminate the orientation of inserted events. In all we can show there are 256 different rejoining paths that are capable of resulting in the visualized complex (data not shown). The scored obligate cycle structure, c2+c3+c3+c4 accounted for less than 1% of all possibilities, whereas the largest rejoining cycles (c12, as illustrated in B, or c10+c2 or c9+c3) accounted for 77% of all possible rejoining paths (data not shown).

The damage induced by the traversal of a α-particle is expected to result in the formation of numerous “hidden” intrachromosome rearrangements; their formation should, however, follow the same scheme. Specifically, our data are consistent with each theoretical rejoining cycle, for each observed complex, representing a single interchromatin space that was intersected by a single α-particle track (30). These spaces form lacunas that both separate chromosome domains and invaginate within domains, and into which chromatin loops may extend. Assuming that an interexchange will only occur at boundary zones of chromosomal domains (38), then the number of individual cycles making up each complex should reflect the number of chromosome–chromosome domain boundaries damaged. Common chromosome domains, but different interchromatin spaces, will then result in the cumulative generation of the observed complex.

In conclusion, we propose that α-particle-induced complex chromosome aberrations arise as products of illegitimate repair of damage induced directly in chromatin loops, with repair most likely occurring after limited movement to the nearest local repair factory. Provided that two or more domains are intersected by an α-particle, the most likely outcome of repair will be the cumulative build-up of a complex chromosome aberration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to John Savage for very useful discussions, advice, and many helpful suggestions in the preparation of this manuscript. Similarly, we thank John Thacker for his comments and advice. We are also indebted to David Papworth for performing all of the statistical analysis, and to Anna Bristow, Samantha Marsden, Stuart Townsend, and Peter Clapham for technical assistance. This work was supported by the United Kingdom Department of Health, Contracts A2.2/RRX 36 and RRX 95.

Abbreviations

M-FISH, multiplex fluorescence in situ hybridization

dsb, double-strand break

PBL, peripheral blood lymphocyte

NEP, nuclear equatorial planes

SEC, sequential exchange complexes

LET, linear energy transfer

References

- 1.Anderson R. M., Marsden, S. J., Wright, E. G., Kadhim, M. A., Goodhead, D. T. & Griffin, C. S. (2000) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 76, 31-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng W., Morrison, D. P., Gale, K. L. & Lucas, J. N. (2000) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 76, 1589-1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tawn E. J., Whitehouse, C. A., Holdsworth, D., Morris, S. & Tarone, R. E. (2000) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 76, 355-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whang-Peng J., Young, R. C., Lee, E. C., Longo, D. L., Schechter, G. P. & DeVita, V. T., Jr. (1988) Blood 71, 403-414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornforth M. N. & Bedford, J. S. (1987) Radiat. Res. 111, 385-405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Natarajan A. T. & Zwanenburg, T. S. (1982) Mutat. Res. 95, 1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown J. M., Evans, J. W. & Kovacs, M. S. (1993) Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 22, 218-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation, (2000) Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation (United Nations, New York), Vol. II, pp. 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durante M., Cella, L., Furusawa, Y., George, K., Gialanella, G., Grossi, G., Pugliese, M., Saito, M. & Yang, T. C. (1998) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 73, 253-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodhead D. T. (1992) Adv. Radiat. Biol. 16, 7-44. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenner T. J., deLara, C. M., O'Neill, P. & Stevens, D. L. (1993) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 64, 265-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodhead D. T. (1999) J. Radiat. Res. 40, 1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savage J. R. & Simpson, P. J. (1994) Mutat. Res. 312, 51-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffin C. S., Marsden, S. J., Stevens, D. L., Simpson, P. & Savage, J. R. (1995) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 67, 431-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.George K., Wu, H., Willingham, V., Furusawa, Y., Kawata, T. & Cucinotta, F. A. (2001) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 77, 175-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grigorova M., Brand, R., Xiao, Y. & Natarajan, A. T. (1998) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 74, 297-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabatier L., Al Achkar, W., Hoffschir, F., Luccioni, C. & Dutrillaux, B. (1987) Mutat. Res. 178, 91-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knehr S., Huber, R., Braselmann, H., Schraube, H. & Bauchinger, M. (1999) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 75, 407-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Speicher M. R., Gwyn Ballard, S. & Ward, D. C. (1996) Nat. Genet. 12, 368-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greulich K. M., Kreja, L., Heinze, B., Rhein, A. P., Weier, H. G., Bruckner, M., Fuchs, P. & Molls, M. (2000) Mutat. Res. 452, 73-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simpson P. J. & Savage, J. R. (1996) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 69, 429-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cornforth M. N. (2001) Radiat. Res. 155, 643-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loucas B. D. & Cornforth, M. N. (2001) Radiat. Res. 155, 660-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson P. J., Papworth, D. G. & Savage, J. R. (1999) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 75, 11-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sachs R. K., Chen, A. M., Simpson, P. J., Hlatky, L. R., Hahnfeldt, P. & Savage, J. R. (1999) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 75, 657-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodhead T. G. (1991) in Genes, Cancer and Radiation Protection, ed. Mendelsohn, M. L. (National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements, Bethesda), pp. 25–37.

- 27.Sachs R. K., Chen, A. M. & Brenner, D. J. (1997) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 71, 1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothkamm K., Kuhne, M., Jeggo, P. A. & Lobrich, M. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 3886-3893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dolling J. A., Boreham, D. R., Brown, D. L., Raaphorst, G. P. & Mitchel, R. E. (1997) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 72, 303-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cremer C., Munkel, C., Granzow, M., Jauch, A., Dietzel, S., Eils, R., Guan, X. Y., Meltzer, P. S., Trent, J. M., Langowski, J. & Cremer, T. (1996) Mutat. Res. 366, 97-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savage J. R. (1993) Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 22, 234-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savage J. R. (1993) Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 22, 198-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Savage J. R. (2000) Science 290, 62-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cremer T. & Cremer, C. (2001) Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 292-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nikiforova M. N., Stringer, J. R., Blough, R., Medvedovic, M., Fagin, J. A. & Nikiforov, Y. E. (2000) Science 290, 138-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ludwikow G., Xiao, Y., Hoebe, R. A., Franken, N. A., Darroudi, F., Stap, J., Van Oven, C. H., Van Noorden, C. J. & Aten, J. A. (2002) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 78, 239-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chadwick K. H. & Leenhouts, H. P. (1978) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. Relat. Stud. Phys. Chem. Med. 33, 517-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Savage J. R. & Papworth, D. G. (1973) Mutat. Res. 19, 139-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.