Abstract

In vitro “glycorandomization” is a chemoenzymatic approach for generating diverse libraries of glycosylated biomolecules based on natural product scaffolds. This technology makes use of engineered variants of specific enzymes affecting metabolite glycosylation, particularly nucleotidylyltransferases and glycosyltransferases. To expand the repertoire of UDP/dTDP sugars readily available for glycorandomization, we now report a structure-based engineering approach to increase the diversity of α-d-hexopyranosyl phosphates accepted by Salmonella enterica LT2 α-d-glucopyranosyl phosphate thymidylyltransferase (Ep). This article highlights the design rationale, determined substrate specificity, and structural elucidation of three “designed” mutations, illustrating both the success and unexpected outcomes from this type of approach. In addition, a single amino acid substitution in the substrate-binding pocket (L89T) was found to significantly increase the set of α-d-hexopyranosyl phosphates accepted by Ep to include α-d-allo-, α-d-altro-, and α-d-talopyranosyl phosphate. In aggregate, our results provide valuable blueprints for altering nucleotidylyltransferase specificity by design, which is the first step toward in vitro glycorandomization.

Keywords: glycosyltransferase, glycorandomization, rational design, enzyme, x-ray crystallography

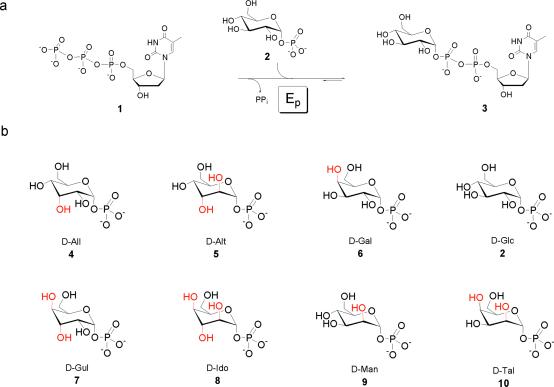

An extensive body of in vivo genetic evidence indicates that the glycosyltransferases involved in secondary metabolism are very promiscuous with respect to their nucleotide diphosphosugar donor (ref. 1 and references therein). Yet, in vitro experiments in this area are limited to only a few examples (2–4), due in part to the lack of the unusual nucleotide diphosphosugar substrates. Thus, the reliance of these unique glycosyltransferases on pyrimidine (uridine/thymidine) diphosphosugars has revitalized interest in methods to expand the repertoire of UDP/dTDP sugars (1, 5–8). Toward this goal, we recently reported that Salmonella enterica LT2 α-d-glucopyranosyl phosphate thymidylyltransferase (Ep), which catalyzes the conversion of α-d-glucopyranosyl phosphate, 1, and dTTP, 2, to dTDP-α-d-glucose, 3, and pyrophosphate (Fig. 1a; ref. 9), can accept a rather wide array of sugar phosphates as substrates in the generation of the corresponding dTDP- and UDP-nucleotide sugars (5, 6). In these studies, a variety of analogs were tested including the entire series of α-d-hexopyranosyl phosphates (5), deoxy-α-d-hexopyranosyl phosphates (5), aminodeoxy-α-d-hexopyranosyl phosphates, and acetamidodeoxy-α-d-hexopyranosyl phosphates (6).

Fig 1.

(a) The reaction catalyzed by Ep. (b) Sugar phosphates used for this study. The corresponding deviations from the natural substrate (2) are highlighted in red.

In an effort to gain a molecular-level understanding of substrate recognition by this unique enzyme, we recently determined the crystal structures of the Salmonella Ep in complex with product, 3, and substrate, 1, at 1.9- and 2.0-Å resolution, respectively (10). The structural elucidation of a related thymidylyltransferase from Pseudomonas also was reported recently (11). These structures reveal a core nucleotide-binding domain, not limited only to sugar nucleotidylyltransferases, responsible for the precise positioning of the nucleophile and activation of the electrophile in enzyme-catalyzed reactions. In conjunction with the kinetic characterization of Ep, this work helped clarify previous mechanistic inconsistencies and suggested that nucleotidylyltransferases in general share a common single displacement mechanism. More importantly, these studies set the stage for engineering a more promiscuous Ep by revealing the precise active site–substrate molecular contacts and allowed a preliminary demonstration of the possibility to alter Ep specificity based on structural insight (10).

While Ep demonstrates surprising sugar phosphate promiscuity, the enzyme does have certain limitations as a general tool for pyrimidine nucleotide sugar synthesis. For example, of the eight possible α-d-hexopyranosyl phosphates (Fig. 1b), wild-type Ep was able to accept only three (α-d-gluco-, 2, α-d-galacto-, 6, and α-d-mannopyranosyl phosphate, 9) to any appreciable extent (6). Herein we report a structure-based engineering approach to increase the diversity of α-d-hexopyranosyl phosphates accepted by Ep. Notably, a single mutant (L89T), engineered to decrease the steric constraints at position C-2 of the substrates, was able to significantly increase the set of α-d-hexopyranosyl phosphates accepted by Ep to include α-d-allo-, 4, α-d-altro-, 5, and α-d-talopyranosyl phosphate, 10. Another variant (Y177F), also targeted at increasing substrate promiscuity at positions C-2 and C-3, was able to turn over α-d-allopyranosyl phosphate, 4. Furthermore, a direct comparison of the active-site structures of these mutants with a previously described mutant (W224H), which displayed high C-6 substrate promiscuity, provides an additional blueprint from which to alter nucleotidylyltransferase specificity by design, which is the first step in an in vitro “glycorandomization” approach for generating diverse libraries of “unnatural” metabolites (10). Given the similarities among members of the nucleotidylyltransferase family, this work also should have general application to purine nucleotide sugar synthesis (12).

Materials and Methods

Materials.

The syntheses of α-d-allopyranosyl phosphate, 4, α-d-altropyranosyl phosphate, 5, α-d-gulopyranosyl phosphate, 7, α-d-idopyranosyl phosphate, 8, and α-d-talopyranosyl phosphate, 10, were reported previously (6), while α-d-galactopyranosyl phosphate, 6, α-d-glucopyranosyl phosphate, 2, and α-d-mannopyranosyl phosphate, 9, were purchased from Sigma. All other chemicals used were reagent-grade and used as supplied except where noted. Routine mass spectra were recorded on a PE SCIEX API 100 liquid chromatography/MS mass spectrometer, and high-resolution MS was accomplished by the University of California, Riverside Mass Spectrometry Facility (Riverside, CA). HPLC was performed on a RAININ Dynamax SD-200 controlled with Dynamax HPLC software.

Protein Expression and Crystallization.

Ep variants were constructed and expressed in Escherichia coli as described (10), and purification followed the protocol for wild-type Ep (5, 6). Purified enzymes were subsequently concentrated to 15–20 mg⋅ml−1 (10 mM KCl/5 mM Hepes, pH 7.4) for crystallization to which ligand (dTTP or UDP-Glc) was added to a 2 mM final concentration (from a 100 mM ligand/H2O stock solution). Equal volumes of protein and well solution were mixed and allowed to equilibrate in a hanging drop by vapor diffusion at room temperature (20°C). Crystals of the Y177F–UDP-Glc complex were obtained against a reservoir of 1.8–1.9 M ammonium sulfate and 5–7.5% (vol/vol) isopropanol. Crystals of the L89T–TTP complex were obtained by using a reservoir solution of 2.0 M ammonium phosphate/10 mM MgCl2/0.1 M Tris buffer, pH 8.5. Finally, the W224H–UDP-Glc complex was crystallized against a reservoir of 0.8 M sodium phosphate/0.8 M potassium phosphate/0.1 M Hepes, pH 7.5.

Data Collection and Structure Determination.

All data were collected in-house by using a Rigaku RAXIS-IV imaging plate area detector or at the National Synchrotron Light Source Brookhaven beamlines X9A or X25. Oscillation images were integrated, scaled, and merged by using DENZO and SCALEPACK (13). All structures were determined with the program AMORE (CCP4; ref. 14) by using the molecular replacement method and either the wild-type Ep–dTTP or Ep–UDP-Glc monomer structure as a search model. Each structure was subsequently refined by using a combination of simulated annealing, energy minimization, and B-factor refinement by using the program X-PLOR (15). Stereochemical analysis of the refined models with the program PROCHECK (CCP4) revealed parameter values better than or within the typical range observed for protein structures determined at corresponding resolutions.

Ep-Catalyzed Conversion.

A reaction containing 2.5 mM NTP, 5.0 mM sugar phosphate, 5.5 mM MgCl2, and 10 units of inorganic pyrophosphatase in a total volume of 50 μl of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, at 37°C was initiated by the addition of 3.52 units of Ep (1 units = the amount of protein needed to produce 1 μmol of TDP-α-d-glucose min−1). The reaction was incubated with slow agitation for 30 min at 37°C, quenched with MeOH (50 μl), and centrifuged (5 min, 14,000 × g), and the supernatant was stored at −20°C until analysis by HPLC. Samples (30 μl) were resolved on a Sphereclone 5u SAX column (250 × 3.2 mm) fitted with a guard column (30 × 3.2 mm) by using a linear gradient (0–200 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 5.0/0.75 ml⋅min−1, A275 nm). Under these conditions, the typical retention times for TTP, UTP, TDP-hexose, and UDP-hexose were 19.8, 18.9, 13.6, and 12.5 min, respectively. HPLC product fractions from the assay were collected, lyophilized, and submitted directly for high-resolution MS (quadrupole time of flight) analysis. The calculated exact mass, in protonated form, is 564.0758 for the anticipated TDP-hexose products and 566.0550 for the anticipated UDP-hexose products, and the experimentally determined values are reported in Table 1. The percent conversion (Table 1) was calculated by using Eq. 1, where AP represents the integration of the nucleotide diphosphosugar product peak, and AT represents the NTP peak integration.

|

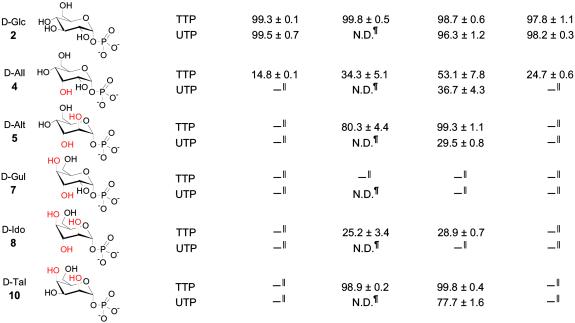

Table 1.

Conversion of sugar phosphates by wild-type and mutant enzymes

The alterations from native substrate (Glc-1-P, 2) are highlighted in red.

Wild-type conversions were reported (6).

Mutants L89T, Y177F, and T201A were pooled and concentrated (see Materials and Methods).

Percent conversion was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. HRMS, TDP-All 563.0677, TDP-Alt 563.0642, TDP-Id 563.0669, TDP-Tal 563.0667, UDP-All 565.0467, UDP-Alt 565.0478.

Not determined.

Represents <6% conversion.

Results and Discussion

Structure-Based Design of Expanded Specificity Ep Mutants.

To extend our efforts to rationally engineer Ep substrate promiscuity, we selected a set of sugar phosphates (the α-d-hexose series; Fig. 1b) containing a number of representatives poorly used by the enzyme. Previous studies revealed wild-type Ep to use only three (α-d-gluco-, 2, α-d-galacto-, 6, and α-d-mannopyranosyl phosphate, 9) of the eight possible α-d-hexopyranosyl phosphates (Fig. 1b) to any appreciable extent with both TTP and UTP (6). A fourth member of this series, α-d-allopyranosyl phosphate, 4, was also shown to convert only in the presence of TTP, and based on these studies it was suggested that Ep prefers pyranosyl phosphates predicted to exist predominately as 4C1 conformers.

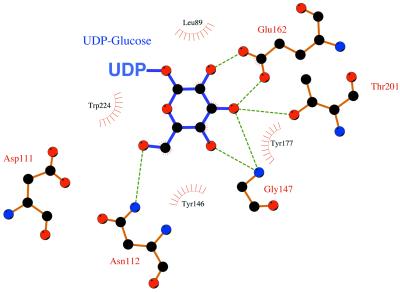

The crystal structures of Ep (10, 11) revealed the molecular details of substrate recognition and substrate specificity of the enzyme, and Fig. 2 provides a schematic representation of the contacts between enzyme and substrate in the active-site pocket of Ep. The sugar moiety sits on a hydrophobic bed composed of Leu-89, Leu-109, and Ile-200 and is positioned by its interaction with several side chains through hydrogen bonding with the sugar hydroxyl groups. Using this model as a guide, we began to systematically mutate residues within the sugar-binding pocket that appeared to hinder the binding of some of the sugars listed in Table 1. Modeling of several sugar phosphates in the active site revealed that both steric and electrostatic constraints precluded their binding. In addition to constraints imposed by side-chain atoms, main-chain atoms also prevented access to some sugars, creating additional challenges to substrate-engineering efforts.

Fig 2.

Schematic representation of Ep and glucose active-site interactions using the program LIGPLOT (19). The glucose moiety of the product, UDP-glucose, and the residues that interact with it in the Ep active site are shown in ball-and-stick format. Hydrogen bonds are illustrated as dashed lines, and hydrophobic interactions are indicated by half circles.

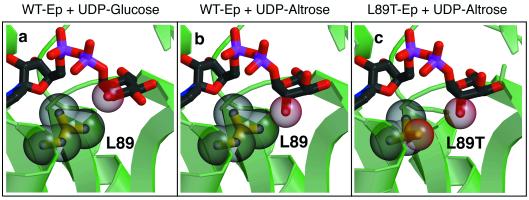

Modeling of the C-2 epimers of glucose (altrose, idose, and talose) indicated that the main infringement came from steric constraints imposed by Leu-89. Indeed, the C-2 oxygen in glucose lies within 4.29 Å of the γ carbon in Leu-89, while the C-2 oxygen in a glucose 2′ epimer (e.g., altrose) would reside 2.88 Å from Leu-89, well within van der Waals contact (Fig. 3). This analysis suggested that a Leu-89 to Thr substitution would relieve steric constraints while simultaneously supplying a potential hydrogen-bonding partner. In a similar fashion, modeling of the C-3 epimers (allose, altrose, gulose, and idose) revealed that main-chain atoms (particularly the Gly-147 amide nitrogen) were preventing access. Furthermore, the side chain of Tyr-177, which lies beneath the glucopyranose ring, appears to prevent sugar phosphates from sitting lower in the active-site pocket. Given the difficulty of peptide backbone alterations within this region, we chose Tyr-177 as the second target for mutagenesis. Conversion of Tyr-177 to Phe, thereby removing the p-OH from the benzene ring of the Tyr, was expected to provide the additional space needed by the axial C-3 and C-2 hydroxyl groups in this epimeric series.

Fig 3.

Fitting altrose in the Ep active site. Close-up views of the structure of wild-type Ep and L89T variant bound to UDP-glucose or modeled UDP-altrose. The entire ligand is illustrated in ball-and-stick format, and the C-2 oxygen atom is shown in space-filling representation. Leu-89 and Thr-89 are depicted in both ball-and-stick and space-filling formats. (a) Wild-type (WT) Ep bound to the product, UDP-glucose. Note the space separating the UDP-glucose C-2 oxygen and Leu-89. (b) The activated sugar, UDP-altrose, is shown modeled in the wild-type Ep active site. Note the steric interference generated when attempting to use this C-2 epimer of glucose as a substrate. (c) Modeled in the active site of L89T is the product UDP-altrose. Observe the separation between Thr-89 and the altrose C-2 oxygen.

Mutant Ep Enzymatic Activities and Their Corresponding Structural Basis.

As a rapid assay for the newly constructed mutants, the proteins were combined, and the mixture was tested directly for the ability to convert compounds 4, 5, 7, 8, and 10. Table 1 reveals that the mutant pool was able to turn over all but one of the sugar phosphates examined (7) in the presence of dTTP including three (5, 8, and 10) of the four α-d-hexopyranosyl phosphates not accepted by wild-type Ep. A deconvolution of the mutant pool by individual analysis surprisingly revealed the bulk of this new activity to derive from a single variant (L89T). Remarkably, the designed L89T mutant leads to the production of six new nucleotide sugars (deriving from the reactions of UTP/4, dTTP/5, UTP/5, dTTP/8, dTTP/10, and UTP/10) as well as nearly a 4-fold improvement in the previously reported dTDP-allose production (6). This result is especially encouraging due to the enhanced promiscuity of L89T without affecting its wild-type traits (e.g., 2). Furthermore, the conversion of 8 (demonstrated to adopt predominately the 4C1 conformer) suggests L89T may accept substrates that adopt alternative chair conformations, adding to the potential utility of this enzymatic process. Yet the lack of conversion of 7, particularly in the context of observed turnover with all other possible α-d-hexopyranosyl phosphates, remains difficult to explain. Finally, Y177F, while modestly enhancing the dTTP/4 reaction, displayed no additional biocatalytic benefits.

In an attempt to understand the structural basis for the activity of our various enzyme variants, each was cocrystallized with either the substrate, dTTP, or the product, UDP-Glc, bound in the active site. We report here the crystal structures of the two mutants discussed above, L89T and Y177F, as well as the structure of a mutant (W224H) we identified previously (10). While Y177F and W224H crystallized in the presence of UDP-Glc, L89T did not and was crystallized instead in the presence of dTTP. Table 2 reports the crystallographic statistics of the data collection and model refinement. As expected, the three structures overall are very similar to the structures of the wild-type enzyme-product and enzyme-substrate complexes. The L89T–dTTP complex superimposes on the wild-type Ep–dTTP complex with an rms deviation of 0.26 Å for the Cα positions of all 289 residues. Similarly, Y177F–UDP-Glc and W224H–UDP-Glc superimpose on the wild-type Ep–UDP-Glc complex with rms deviations of 0.42 and 0.46 Å, respectively.

Table 2.

Summary of crystallographic data: Ep mutants

| Crystal | L89T–TTP | Y177F–UDG | W224H–UDG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution, Å | 2.2 | 2.75 | 2.2 |

| Wavelength, Å | 1.072 | 1.54 | 1.14 |

| Completeness, % | 95.0 | 98.3 | 94.3 |

| Redundancy, fold | 4 | 5 | 17.5 |

| I/σI | 24.3 | 18.2 | 40.1 |

| Rmerge | 4.9 | 6.1 | 6.1 |

| Space Group | P43212 | P212121 | P6522 |

| Cell Dimensions, Å | a = b = 120, c = 94 | a = 91, b = 111, c = 131 | a = b = 88, c = 329 |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution, Å | 8–2.2 | 8–2.75 | 8–2.2 |

| Reflections working/test | 29,105/3,206 | 30,716/3,486 | 34,900/3,911 |

| Nonhydrogen atoms | 4,626 | 9,172 | 4,580 |

| Rcrys/Rfree | 24.3/28.1 | 22.9/29.2 | 25.7/28.9 |

| rms deviations | |||

| Bonds, Å | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.007 |

| Angles, ° | 1.30 | 1.34 | 1.26 |

Rsym = Σ|I − 〈I〉|/ΣI, where I = observed intensity and 〈I〉 = average intensity obtained from multiple observations of symmetry related reflections. rms bond lengths and rms bond angles are the respective root-mean-square deviations from ideal values. Rcrys and Rfree are the respective R factor and free R factor of the crystal (using 10% of the data as the test set).

Modeling of altrose in the active-site pocket of L89T, Fig. 3c, reveals that the γ oxygen in Thr-89 would now be ≈3.9 Å away from the C-2 hydroxyl. As predicted, this gain in over 1 Å at C-2 clearly is consistent with the ability of L89T to accept 5, 8, and 10. Furthermore, our structure of L89T suggests that in addition to relieving C-2 steric constraints, this mutation also might alleviate infringements at C-3 and C-4 via a potential adjustment or “slipping” of the sugar base in the enlarged active-site pocket. Such slipping also could explain the ability to accept alternative chair conformations, and the enhanced turnover of 4 and the turnover of 8 are consistent with this postulation. Cumulatively, the success of this designed mutation was exceptionally high in that three of the four substrates, for which this mutation was designed, became successful substrates. In this particular example, the design, anticipated result, and experimental determinations are consistent and highlight the potential of rational enzyme engineering.

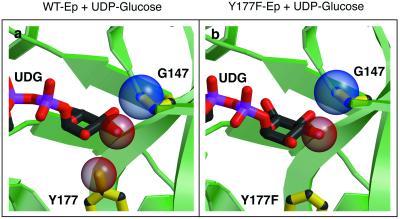

In contrast, Y177F, designed specifically to relieve constraints imposed on the C-3 epimers, was relatively less successful in that a 2-fold enhancement of 4 conversion was the only observable biocatalytic benefit. The Y177F mutant structure (Fig. 4) reveals that, as designed, there is adequate room for movement of the sugar base lower into the binding pocket. Indeed, in the Y177F structure, the UDP-Glc has moved slightly down in the pocket in comparison to the wild-type enzyme. However, (i) this small movement is not sufficient for effective binding of the other C-3 epimers, (ii) this slip may lead to a misalignment of substrates and the essential enzyme catalytic residues, and/or (iii) the hydrogen-bond contacts of the sugar perimeter lack flexibility and thus lock the sugar into a predefined wild-type position. In the L89T mutation, this “lock” might be broken by the energy of formation of a potential new hydrogen bond, which the introduction of threonine allows. In this second example, the structure-based design and anticipated structural consequences are consistent. Yet, the determined catalytic consequences of this rational design were not what we anticipated, and thus this example highlights one unexpected aspect of “rational-design” methodology.

Fig 4.

Comparison between wild-type (WT) Ep and Y177F active sites. The ligand, UDP-glucose, is illustrated in ball-and-stick format, as are Gly-147, Tyr-177, and Phe-177. Space-filling representations are shown for the side-chain oxygen in Tyr-177, the main-chain nitrogen of Gly-147, and the C-2 oxygen of UDG. (a) Close-up view of the Ep–UDP-glucose complex active site (left). Note the distance between the backbone nitrogen of Gly-147 and the UDP-glucose C-3 oxygen. An axial oxygen at this position would probably result in steric clashes. (b) A close-up view of the Y177F–UDP-glucose active site. Observe the tilt in the glucose ring in this model. The C-6 oxygen is now in view. Also, notice the slight increase in distance between the nitrogen of Gly-147 and the UDP-glucose C-3 oxygen.

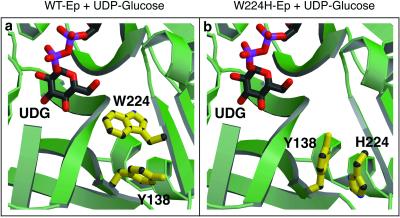

The reported W224H mutant also was included in this analysis, because this mutant was found to display unusually high C-6 substrate promiscuity (10). The original design of this mutation also was based on the wild-type structure that illustrated the W224 indole side chain to reside within 3.6 Å of the substrate C-6-OH. In constructing W224H, we intended to minimize the C-6 steric infringement of the side chain (indole to imidazole) while simultaneously providing a partial positive charge to relieve electrostatic constraints generated by sugars such as glucuronic acid. As expected, this designed mutant manifested the ability to accept a wide array of new substitutions at C-6, and therefore a detailed structural analysis would be informative to future structure-based design.

Interestingly, the structural elucidation of this mutant reveals that an astonishing active-site side-chain rearrangement creates a large gap surrounding C-6, clearly consistent with its impressive substrate promiscuity (Fig. 5). The inserted histidine now hydrogen-bonds to the main-chain carbonyl of Met-218 and is rotated about the χ axis 180° from the original position of W224. In addition to rotating, the Cα of H224 has moved 2.43 Å from the position occupied by the Cα of W224 in the wild-type enzyme, inducing a large local main-chain distortion in this area of the substrate-binding pocket. Moreover, Y138 has also rotated 90° about the χ axis to allow for the movement of the mutated histidine. As an illuminating example of the unexpected in rational design, this case is one in which the design expectations and catalytic outcome are consistent, but the structural basis is significantly distinct from the predicted structural consequences of the given mutation.

Fig 5.

Effects of main-chain distortion in the W224H variant. The ligand, UDP-glucose, is illustrated in ball-and-stick format, as are Ep residues Tyr-138, Trp-224, and His-224. (a) The wild-type (WT) Ep active site showing the position of Trp-224 and Tyr-138 relative to the product UDP-glucose. Note the distance between the UDP-glucose C-6 oxygen and the Trp-224 side chain. (b) The W224H active site showing the large movement of His-224 relative to Trp-224 in a. Also, note the large difference in conformation of Tyr-138. It rotates almost 180° to accommodate His-224. Movement of these side chains opens up a large gap surrounding C-6.

Applications of Nucleotide Sugar Libraries.

Ep demonstrates a unique ability to activate a wide range of “natural” and “unnatural” sugar substrates (5, 6). Furthermore, as described, the structure-based engineering of this nucleotidylyltransferase has been extensively productive in generating modified enzymes capable of using an even larger set of unnatural sugars previously not accepted by wild-type Ep (10). In the context of the significant promiscuity displayed by glycosyltransferases of secondary metabolism and the availability of appropriate aglycons, the Ep-catalyzed production of nucleotide diphosphosugar-donor libraries is a particularly promising approach toward the generation a diverse library of glycorandomized structures based on a particular natural product scaffold. Furthermore, given that glycosylation often defines pharmacological [for example, 4-epidoxorubicin versus doxorubicin (16)] and/or biological [for example, erythromycin versus megalomicin (17) or differentially glycosylated vancomycins (18)] properties, this approach has significant potential for drug discovery. An expansion of this approach into the purine-using nucleotidylyltransferases/glycosyltransferase holds exciting promise as well.

Acknowledgments

We thank the PhRMA Foundation for predoctoral fellowship support (to J.B.B.). This work was supported in part by the Bressler Foundation (to D.B.N.), National Institutes of Health Grants GM58196, CA84374, and AI52218, and the Mizutani Foundation for Glycoscience (to J.S.T.). D.B.N. is a PEW Fellow and a Bressler Scholar. J.S.T. is an Alfred P. Sloan Fellow and a Rita Allen Foundation Scholar.

Abbreviations

Ep, LT2 α-d-glucopyranosyl phosphate thymidylyltransferase

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (PDB ID codes , , and ).

References

- 1.Thorson J. S., Hosted, T. J., Jr., Jiang, J., Biggins, J. B., Ahlert, J. & Ruppen, M. (2001) Curr. Org. Chem. 5, 139-167. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solenberg P. J., Matsushima, P., Stack, D. R., Wilkie, S. C., Thompson, R. C. & Baltz, R. H. (1997) Chem. Biol. 4, 195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Losey H. C., Peczuh, M. W., Chen, Z., Eggert, U. S., Dong, S. D., Pelczer, I., Kahne, D. & Walsh, C. T. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 4745-4755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulichak A. M., Losey, H. C., Walsh, C. T. & Garavito, R. M. (2001) Structure (London) 9, 547-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang J., Biggins, J. B. & Thorson, J. S. (2001) Angew. Chem. Intl. Ed. Engl. 40, 1502-1505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang J., Biggins, J. B. & Thorson, J. S. (2000) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 6803-6804. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koeller K. M. & Wong, C.-H. (2000) Nat. Biotechnol. 18, 835-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elhalabi J. M. & Rice, K. G. (1999) Curr. Med. Chem. 6, 93-116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindquist L., Kaiser, R., Reeves, P. R. & Lindberg, A. A. (1993) Eur. J. Biochem. 211, 763-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barton W. A., Lesniak, J., Biggins, J. B., Jeffrey, P. D., Jiang, J., Rajashankar, K. R., Thorson, J. S. & Nikolov, D. B. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 545-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blankenfeldt W., Asuncion, M., Lam, J. S. & Naismith, J. H. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 6652-6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watt G. M., Flitsch, S. L., Fey, S., Elling, L. & Krag, U. (2000) Tetrahedron Asymmetry 11, 621-628. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otwinowski Z. & Minor, W., (1993) Data Collection and Processing (Science and Engineering Research Council Daresbury Laboratory, Warrington, U. K.), pp. 556–562.

- 14.The Collaborative Computational Project 4 (1994) Acta Crystallogr. D 50, 760-776.15299374 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brünger A. T., (1993) X-PLOR 3.1 Manual (Yale University, New Haven, CT).

- 16.Madduri K., Kennedy, J., Rivola, G., Inventi-Solari, A., Filippini, S., Zanuso, G., Colombo, A. L., Gewain, K. M., Occi, J. L., MacNeil, D. J. & Hutchinson, C. R. (1998) Nat. Biotechnol. 16, 69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Volchegursky Y., Hu, Z., Katz, L. & McDaniel, R. (2000) Mol. Microbiol. 37, 752-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ge M., Chen, Z., Onishi, H. R., Kohler, J., Silver, L. L., Kerns, R., Fukuzawa, S., Thompson, C. & Kahne, D. (1999) Science 284, 507-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallace A. C., Laskowski, R. A. & Thornton, J. M. (1995) Protein Eng. 8, 127-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]