Abstract

Synthetic carbohydrate cancer vaccines have been shown to stimulate antibody-based immune responses in both preclinical and clinical settings. The antibodies have been observed to react in vitro with the corresponding natural carbohydrate antigens expressed on the surface of tumor cells, and are able to mediate complement-dependent and/or antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Furthermore, these vaccines have proven to be safe when administered to cancer patients. Until recently, only monovalent antigen constructs had been prepared and evaluated. Advances in total synthesis have now enabled the preparation of multivalent vaccine constructs, which contain several different tumor-associated carbohydrate antigens. Such constructs could, in principle, serve as superior mimics of cell surface antigens and, hence, as potent cancer vaccines. Here we report preclinical ELISA-based evaluation of a TF–Ley–Tn bearing construct (compound 3) with native mucin glycopeptide architecture and a Globo-H–Ley–Tn glycopeptide (compound 4) with a nonnative structure. Mice were immunized with one or the other of these constructs as free glycopeptides or as keyhole lymphet hemocyanin conjugates. Either QS-21 or the related GPI-0100 were coadministered as adjuvants. Both keyhole lymphet hemocyanin conjugates induced IgM and IgG antibodies against each carbohydrate antigen, however, the mucin-based TF–Ley–Tn construct was shown to be less antigenic than the unnatural Globo-H–Ley–Tn construct. The adjuvants, although related, proved significantly different, in that GPI-0100 consistently induced higher titers of antibodies than QS-21. The presence of multiple glycans in these constructs did not appear to suppress the response against any of the constituent antigens. Compound 4, the more antigenic of the two constructs, was also examined by fluorescence activated cell sorter analysis. Significantly, from these studies it was shown that antibodies stimulated in response to compound 4 reacted with tumor cells known to selectively express the individual antigens. The results demonstrate that single vaccine constructs bearing several different carbohydrate antigens have the potential to stimulate a multifaceted immune response.

Keywords: conjugate vaccines‖synthetic vaccines‖multivalent‖polyvalent vaccines

The level of expression of cell surface carbohydrate antigens is often significantly increased on carcinogenic transformation, and, in some cases, the expression of particular antigens appears to be associated primarily with the transformed state (1, 2). Thus, carbohydrate-based antigens offer the potential for a targeted immunotherapeutic approach to the treatment of certain forms of cancer. The development of effective cancer vaccines based on carbohydrate antigens is an extremely challenging undertaking, however, and there are potential impediments to the success of such an endeavor. The first of these is related to the inherently low immunogenicity that the native carbohydrate antigens may exhibit. To mount an effective active immune response, this immune tolerance to the “self-antigens” must be overcome. Another factor that must be addressed en route to the development of carbohydrate-based cancer vaccines is that their isolation from natural sources is an extremely arduous task, and typically results in only minute quanties of material being obtained. Although the realization of an immunological approach to cancer control using carbohydrate-based vaccine constructs is clearly a nontrivial undertaking, efforts of this sort appear well justified, as there is considerable evidence supporting the notion that naturally acquired, actively induced, or passively administered antibodies directed against carbohydrate antigens are able to mitigate against circulating tumor cells and micrometastases (3, 4).

We have been engaged in the development of cancer vaccines based on carbohydrate motifs (5). To overcome the complexities associated with the isolation of tumor antigens from natural sources, we have developed a total synthesis program, which allows us to chemically synthesize such antigens, even those of complex structure (6). When our approach is used, the chemically homogenous antigens are obtained in a form that allows facile conjugation to an immunogenic carrier protein. Sufficient quantities of these constructs can readily be synthesized to support preclinical and clinical evaluation. We have, on several occasions, demonstrated that covalent attachment of the antigen constructs to an immunogenic carrier protein, and coadministration of the resulting conjugate vaccine with an immunological adjuvant, leads to a clear humoral response (7). Our experiences so far have focused on the use of keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) as the carrier protein, along with QS-21 as the adjuvant (7). Vaccination based on such protocols has proven effective in eliciting antibody responses against a variety of cell surface tumor antigens (8). At least to date, this modus operandi has proven to be more effective than the use of other carrier molecules (7) and other adjuvants (7, 9, 10).

Initially, our program focused on the development of vaccines based on individual glycolipid antigens attached to KLH (11–16). We refer to these as monomeric conjugate vaccines. Later, we examined synthetic mucin-based antigen conjugates, in which several copies of a particular antigen were displayed within a single construct, a format that we refer to as clustered conjugate vaccines (11–13, 15–17). Recently, monomeric vaccines based on Globo-H and Ley (13, 16, 18, 19), and clustered constructs containing Tn and TF§,¶ have been advanced to the clinic for the treatment of breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer recurrence. Approaches involving these particular constructs have targeted one antigen per vaccine. It is typically the case, however, that several different carbohydrate antigens are associated with a given cancer type, and these antigens are likely expressed at varying levels during the phases of cellular development (1, 2). Consequently, vaccine-based approaches involving a single antigen may neglect a significant population of transformed cells.

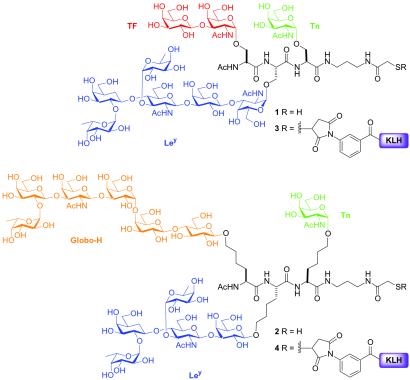

In principle, vaccination strategies that target a range of tumor-associated antigens should lead to a diverse immune response, in which the likelihood of immunoevasion by heterogenous cell types is reduced. In this connection, we wondered whether a single vaccine construct bearing multiple tumor antigens could be developed. To this end, we have prepared two distinct glycopeptide constructs, each containing three different antigens. We refer to these species as multivalent conjugate vaccines. One construct closely adheres to the known characteristics of mucin glycopeptide architecture (20), i.e., the core glycan is a GalNAc α-O-linked to serine, and displays the TF, Ley, and Tn antigens (1, Fig. 1). The other construct does not embody the natural α-O-linked GalNAc, and displays Globo-H, Ley, and Tn on Tris-homoserine residues (2, Fig. 1). In both cases, the glycoamino acids are presented in a format reminiscent of microheterogeneous cell surface glycoproteins. Our hope in developing these constructs was that vaccination with a single KLH conjugate, which displayed several different antigens, would stimulate a multifaceted immune response converging on a particular form of cancer. The focus of this investigation was primarily to establish the feasibility of such an immune response, which would then justify the development of more sophisticated vaccine constructs in which each of the antigens were displayed in a clustered format. It is well to note that, before the present investigation, single entity vaccination with multivalent carbohydrates conjugated to an immunogenic carrier had not been reported, which is no doubt a result of the complexities associated with the synthesis of such systems. For the purposes of our study, we focused on four of our most extensively immuno-characterized carbohydrate antigens. Our intention was to allow for meaningful immunological and, eventually, clinical comparisons, while developing potentially effective cancer therapies.

Figure 1.

Fully synthetic multivalent constructs 1–4.

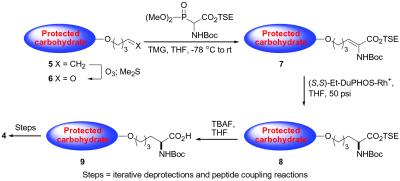

From the outset of our investigations, we wondered about the effect that the differential modes of carbohydrate presentation (i.e., naturally occurring mucin-based, versus nonnaturally occurring Tris-homoserine-based) might have on the immunogenicity of the conjugate vaccines. It was indeed interesting to note that, in preliminary ELISA investigations (data not shown), of the two conjugate vaccines, the Tris-homoserine construct 4 appeared to be considerably more antigenic than the naturally inspired mucin-based species 3. Accordingly, we have focused on construct 4 for thorough immunological analysis, including an expanded ELISA-based investigation, and fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS)-based analysis. Synthetic access to compound 4 was possible as a result of methodology recently developed in our laboratory for the elaboration of n-pentenylglycosides to glycoamino acid conjugates (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

General procedure for formation of glycoamino acid conjugates from n-pentenyl glycosides.

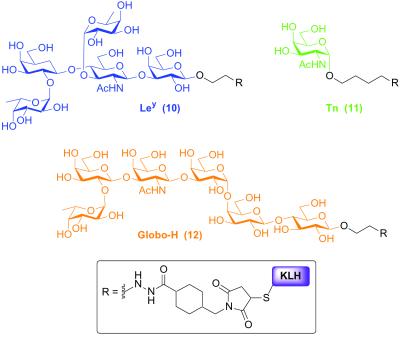

In the study described herein, we examined the immunological properties of compound 4 when administered in the presence of QS-21 (21), or, for comparison purposes, the related, but less toxic adjuvant GPI-0100 (22). As controls, we evaluated the immunogenicity of the nonconjugated compound 2, and conducted a concurrent investigation on a mixture containing each of the monomeric antigens conjugated to KLH (10, 11, and 12, Fig. 3). The later experiment was conducted for the purposes of comparing the response by a single mouse to each of the individual antigens, in response to vaccination with the polyvalent construct versus the mixture of monomers. To address issues relating to vaccine formulation, we determined the level of immune response directed against each antigen, within the construct. Furthermore, in anticipation of clinical trials, we assessed the ability of antibodies, so generated, to react in vitro with human cell lines known to express the individual antigens.

Figure 3.

Monomeric controls used in vaccination study.

Materials and Methods

Vaccine Preparation.

Conjugate vaccines 3 and 4 were prepared as follows. KLH (Sigma; molecular weight = 8.6 × 106) was modified by using m-malemidobenzoyl-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (Pierce) as described (23). Construct 1, containing TF, Ley, and Tn, and construct 2, containing Globo-H, Ley, and Tn, were prepared by total synthesis using solution phase peptide synthesis from the appropriately protected constituent glycoamino acids (24, 25). The sulfhydryl function was incorporated to facilitate attachment to KLH. Global deprotection of the synthetic material revealed compounds 1 and 2. Addition of construct 1 or 2 to the maleimide-derivatized KLH was achieved by incubating the mixture at room temperature for 3 h, followed by removal of the unreacted synthetic glycopeptide peptide by using a 30,000 molecular cutoff Centriprep filter (23).

Animals and Vaccinations.

Groups of five female C57BL mice (6 weeks of age; The Jackson Laboratory) were immunized s.c. as follows: group 1, immunized with construct 2 (10 μg), plus QS-21 (10 μg) (Antigenic, New York); group 2, immunized with 2 (10 μg), plus KLH (not conjugated to 2), plus QS-21 (10 μg); group 3, immunized with 4 (3 μg), plus QS-21 (10 μg); group 4, immunized with 4 (3 μg), plus GPI-0100 (100 μg) (Galenica Pharmaceuticals, Birmingham, AL); group 5, immunized with a mixture containing 10, 11, and 12 (3 μg each), plus QS-21 (10 μg). Mice were immunized on days 1, 7, and 14, and bled 10 days after the third vaccination.

Serological Analyses.

ELISA.

ELISAs were performed as described (8). Briefly, ELISA plates were coated with either synthetic Globo-H-ceramide, or Ley and Leb expressing mucin purified from ovarian cyst fluid (26), or Tn-HSA, or Globo-H–Ley–Tn-HSA in 0.1 M carbonate buffer (pH 11), at 0.3 μg/well for glycolipids and 0.2 μg/well for glycoproteins. Serially diluted antiserum was added to each well, and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM or anti-mouse IgG was added at a dilution of 1:200 (Southern Biotechnology Associates). ELISA titers are defined as the highest dilution yielding an absorbance of 0.1 or greater over that of normal control mouse sera.

Cell surface reactivity determined by FACS.

The cell surface reactivity of immune sera was tested on human cell lines as described (8). Briefly, reactivity was assessed by using anti-Globo-H, anti-Ley, and anti-Tn antibodies tested on MCF-7 (Globo-H and Ley positive) and LS-C (Tn and Ley positive) cells (provided by S. H. Itzkowitz, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York) (27). Single cell suspensions of 2 × 105 cells per tube were washed in PBS with 3% FCS and 0.01M NaN3 and incubated with 20 μl of 1:20 diluted antisera or monoclonal antibodies for 30 min on ice. The positive control mAbs were VK-9 against synthetic Globo-H (28), 3S193 against Ley (29), and αTn against Tn (DAKO). After two washes with 3% FCS in PBS, 20 μl of 1:25 diluted goat anti-mouse IgM or IgG-labeled with FITC was added, and the mixture incubated for 30 min. After a final wash, the positive population and mean fluorescence intensity of stained cells were differentiated by using FACScan (Becton Dickinson).

Results

Antibody Response Against Globo-H–Ley–Tn Construct (2).

ELISA antibody titers against Globo-H–Ley–Tn in sera from mice immunized with 4 was determined and results are summarized in Table 1. Relatively strong IgM and IgG titers were detected in mice vaccinated with 4, compared with prevaccination sera, which showed no IgG and IgM titers. Construct 4 induced both IgM and IgG antibodies, with the GPI-0100 group inducing significantly higher titers compared with the QS-21 group. Group 5 induced very low IgM and IgG titers against the multivalent construct (see Table 1) when compared with groups 3 and 4.

Table 1.

Vaccination-induced ELISA-based antibody titers

| (Group) Vaccine Formulation | Mouse* | Against multivalent construct

|

Against Globo-H

|

Against Lev

|

Against Tn

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before vaccination

|

10 days after third vaccination

|

Before vaccination

|

10 days after third vaccination

|

Before vaccination

|

10 days after third vaccination

|

Before vaccination

|

10 days after third vaccination

|

|||||||||||

| IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | |||

| (1) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 10 μg Globo-H–Ley–Tn + 10 μg QS-21 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 640 | 0 | 320 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 160 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | ||

| 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 160 | 80 | 40 | 0 | 160 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 0 | ||

| Median | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| (2) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 10 μg Globo-H–Ley–Tn + KLH (nonconjugated) + 10 μg QS-21 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2.1 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 320 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 0 | ||

| 2.2 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 640 | 0 | 80 | 320 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 320 | ||

| 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 320 | ||

| 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 320 | 160 | 0 | 320 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 160 | ||

| 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 320 | 80 | 0 | 160 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 160 | ||

| Median | 0 | 0 | 160 | 320 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 160 | ||

| (3) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3 μg Globo-H–Ley–Tn–KLH + 10 μg QS-21 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3.1 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 5120 | 160 | 0 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 320 | ||

| 3.2 | 0 | 0 | 640 | 10240 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 0 | ||

| 3.3 | 0 | 0 | 1280 | 10240 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 80 | ||

| 3.4 | 0 | 0 | 640 | 2560 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 320 | ||

| 3.5 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 10240 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 80 | ||

| Median | 0 | 0 | 640 | 10240 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 160 | ||

| (4) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3 μg Globo-H–Ley–Tn–KLH + 100 μg GPI-0100 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4.1 | 0 | 0 | 640 | 40960 | 80 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 160 | ||

| 4.2 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 20480 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 160 | ||

| 4.3 | 0 | 0 | 2560 | 40960 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 640 | ||

| 4.4 | 0 | 0 | 2560 | 20480 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 640 | 320 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 640 | ||

| 4.5 | 0 | 0 | 1280 | 40960 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1280 | 1280 | ||

| Median | 0 | 0 | 1280 | 40960 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 640 | ||

| (5) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3 μg Globo-H–KLH, 3 μg Ley–KLH, 3 μg Tn–KLH + 10 μg QS–21 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5.1 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 640 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 1280 | 81920 | ||

| 5.2 | 0 | 0 | 640 | 320 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 160 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 320 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 10240 | ||

| 5.3 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 5120 | 81920 | ||

| 5.4 | 0 | 0 | 1280 | 640 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 160 | 0 | 0 | 1280 | 163840 | ||

| 5.5 | 0 | 0 | 2560 | 1280 | 160 | 0 | 320 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 1280 | 40960 | ||

| Median | 0 | 0 | 640 | 640 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 1280 | 81920 | ||

Each number corresponds to an individual mouse.

Antibody Response Against Globo-H Ceramide.

ELISA antibody titers against Globo-H-ceramide in sera from mice immunized with 4 were determined. As summarized in Table 1, weak IgM titers were detected in prevaccination sera, while sera obtained after vaccination with 4 showed increased IgM and IgG titers. No difference in IgM titers between groups 3 and 4 was detected. However, the group receiving QS-21 induced IgG antibodies against Globo-H, whereas the group receiving GPI-0100 failed to do so. Sera obtained from group 5 reacted with Globo-H, relative to all other groups.

Antibody Response Against Ley.

ELISA antibody titers against Ley in sera from mice immunized with 4 were tested and the results are summarized in Table 1. With the exception of group 1, no detectable anti-Ley antibodies were present in prevaccination sera. In general, sera obtained after vaccination with 4, or a mixture of three vaccines, reacted relatively strongly with Ley by ELISA. Construct 4 induced both IgM and IgG antibodies against Ley. No difference in antibody production was observed between groups 3 and 4, having received QS-21 and GPI-0100, respectively. No difference in antibody titers was observed between mice immunized with construct 4, or with a mixture containing monomeric constructs 10, 11, and 12.

Antibody Response Against Tn Antigen.

ELISA antibody titers against Tn-HSA in sera from mice immunized with 4 and mixture of constructs 10, 11, and 12 were determined. As summarized in Table 1, no IgM or IgG activity was detected in prevaccination sera. Groups 3 and 4 induced both IgM and IgG titers against Tn, but the adjuvant GPI-0100 induced 1-fold higher titer than adjuvant QS-21. Group 5 also showed high IgG titers against Tn antigen.

Cell Surface Reactivities.

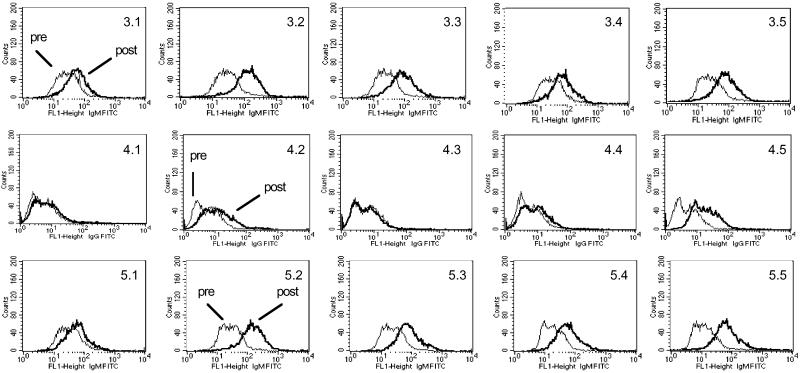

Cell surface reactivity of the sera was tested by flow cytometry using MCF-7 (Globo-H, Ley and Tn positive) and LS-C (Tn and Ley positive) cell lines. The results are summarized in Table 2, and the histograms of FACS against MCF-7 for groups 3, 4, and 5 are presented in Fig. 4. Sera obtained from all prevaccinated mice showed minimal reactivity (<10% positive cells). After vaccination, groups 3, 4, and 5 showed significant IgM reactivity and low IgG reactivity against MCF-7 cells. No significant difference in cell surface reactivity against MCF-7 was observed with sera obtained after vaccination with construct 4 (group 3) or a mixture of constructs 10, 11, and 12 (group 5). There also did not appear to be a difference in cell surface reactivity between the adjuvants QS-21 (group 3) and GPI-0100 (group 4).

Table 2.

FACS assay on MCF-7 and LSC cell lines with immune sera obtained before and after immunization

| (Group) Vaccine formulation | Mouse* | % positive cells by FACS (MFI)*

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 human breast cell line

|

LSC human colon cell line

|

||||||||

| Before serum

|

After serum

|

Before serum

|

After serum

|

||||||

| IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | ||

| (1) | |||||||||

| 10 μg Globo-H–Ley–Tn + 10 μg QS-21 | |||||||||

| 1.1 | 10 (21) | 11 (12) | 5 (18) | 11 (11) | 10 (31) | 10 (12) | 12 (36) | 12 (14) | |

| 1.2 | 9 (13) | 9 (12) | 31 (18) | 8 (9) | 11 (30) | 10 (17) | 11 (31) | 11 (15) | |

| 1.3 | 10 (15) | 11 (10) | 15 (17) | 9 (11) | 10 (52) | 10 (12) | 10 (50) | 11 (12) | |

| 1.4 | 10 (5) | 11 (9) | 28 (11) | 16 (11) | 11 (28) | 10 (10) | 7 (22) | 15 (14) | |

| 1.5 | 10 (14) | 10 (5) | 29 (20) | 15 (26) | 10 (32) | 11 (11) | 10 (32) | 14 (14) | |

| Median | 10 (14) | 11 (10) | 28 (18) | 11 (11) | 10 (31) | 10 (12) | 10 (32) | 12 (14) | |

| (2) | |||||||||

| 10 μg Globo-H–Ley–Tn + KLH (nonconjugated) + 10 μg QS-21 | |||||||||

| 2.1 | 10 (51) | 10 (12) | 31 (65) | 11 (11) | 10 (20) | 11 (13) | 15 (21) | 18 (17) | |

| 2.2 | 11 (44) | 10 (10) | 43 (79) | 18 (16) | 11 (19) | 11 (13) | 24 (29) | 29 (19) | |

| 2.3 | 11 (41) | 9 (9) | 68 (99) | 13 (15) | 10 (34) | 11 (11) | 22 (50) | 14 (12) | |

| 2.4 | 11 (38) | 10 (7) | 82 (127) | 20 (16) | 11 (54) | 11 (17) | 12 (61) | 23 (37) | |

| 2.5 | 10 (44) | 10 (10) | 51 (86) | 20 (16) | 10 (20) | 11 (11) | 45 (67) | 21 (19) | |

| Median | 11 (44) | 10 (10) | 51 (86) | 18 (16) | 10 (20) | 10 (13) | 22 (50) | 21 (19) | |

| (3) | |||||||||

| 3 μg Globo-H–Ley–Tn–KLH + 10 μg QS-21 | |||||||||

| 3.1 | 10 (42) | 11 (8) | 46 (62) | 20 (11) | 10 (14) | 11 (22) | 20 (18) | 7 (17) | |

| 3.2 | 11 (34) | 10 (5) | 93 (144) | 48 (18) | 10 (13) | 10 (5) | 70 (32) | 68 (24) | |

| 3.3 | 11 (36) | 11 (10) | 76 (109) | 26 (16) | 10 (64) | 10 (25) | 18 (94) | 30 (68) | |

| 3.4 | 11 (43) | 11 (7) | 53 (89) | 23 (12) | 10 (70) | 11 (52) | 20 (107) | 14 (60) | |

| 3.5 | 11 (33) | 11 (7) | 77 (95) | 39 (15) | 10 (62) | 10 (20) | 24 (95) | 38 (53) | |

| Median | 11 (36) | 11 (7) | 76 (95) | 26 (15) | 10 (62) | 10 (22) | 20 (94) | 30 (53) | |

| (4) | |||||||||

| 3 μg Globo-H–Ley–Tn–KLH + 100 μg GPI-0100 | |||||||||

| 4.1 | 11 (33) | 10 (8) | 47 (65) | 17 (10) | 11 (13) | 10 (8) | 23 (18) | 25 (13) | |

| 4.2 | 12 (39) | 10 (8) | 66 (102) | 36 (25) | 10 (16) | 10 (10) | 31 (26) | 43 (17) | |

| 4.3 | 10 (37) | 10 (11) | 73 (100) | 8 (11) | 11 (71) | 10 (28) | 18 (122) | 19 (50) | |

| 4.4 | 12 (41) | 10 (7) | 87 (167) | 23 (12) | 11 (63) | 9 (23) | 72 (251) | 36 (67) | |

| 4.5 | 11 (34) | 10 (8) | 55 (76) | 57 (26) | 10 (58) | 10 (22) | 13 (66) | 29 (54) | |

| Median | 11 (37) | 10 (8) | 66 (100) | 23 (12) | 11 (58) | 10 (22) | 23 (66) | 29 (50) | |

| (5) | |||||||||

| 3 μg Globo-H–KLH, 3 μg Ley–KLH, 3 μg Tn–KLH + 10 μg QS-21 | |||||||||

| 5.1 | 12 (47) | 11 (10) | 41 (69) | 14 (11) | 10 (14) | 10 (13) | 14 (17) | 16 (24) | |

| 5.2 | 12 (35) | 10 (8) | 96 (175) | 16 (10) | 9 (21) | 10 (10) | 32 (44) | 22 (12) | |

| 5.3 | 10 (34) | 10 (9) | 77 (105) | 23 (12) | 10 (17) | 11 (27) | 78 (131) | 29 (53) | |

| 5.4 | 11 (31) | 10 (7) | 69 (75) | 30 (16) | 11 (91) | 10 (23) | 7 (73) | 22 (36) | |

| 5.5 | 12 (17) | 9 (7) | 96 (89) | 25 (11) | 10 (69) | 10 (27) | 18 (110) | 52 (70) | |

| Median | 12 (34) | 10 (8) | 77 (89) | 23 (11) | 10 (21) | 10 (23) | 18 (73) | 22 (36) | |

Mean fluorescence intensity. Monoclonal antibody 3S193 (IgG) showed 99%, VK-9 showed 42% on MCF-7; 3S193 (IgG) showed 78%, HB-Tn-1 showed 91% on LSC.

Figure 4.

Analysis of cell surface reactivity of IgM and IgG antibodies in sera from mice immunized with construct 4 against MCF-7 by FACS.

Discussion

The model underlying the treatment of cancer patients with synthetic conjugate vaccines, based on cell-surface antigens in the adjuvant setting, is that of vaccination with bacterial polysaccharides in the area of infectious diseases. In that case, antibodies prevent infection through the elimination of circulating pathogens. Antibodies stimulated via synthetic tumor-associated carbohydrate antigens might have the potential to suppress and eliminate circulating tumor cells associated with micrometastases. Although carbohydrate-based antigens are relatively weakly immunogenic, conjugation to highly immunogenic carriers frequently succeeds in inducing robust immune responses against the desired epitope (30–33).

To date, we have advanced several carbohydrate-based cancer vaccines to clinical trials. In an effort to broaden the range of anti-tumor antibodies generated by vaccination, we have evaluated the antibody-stimulating properties of two multivalent constructs in mice. Vaccine candidates 3 and 4 were prepared by conjugating the totally synthetic glycopeptides 1 and 2, respectively, to the highly immunogenic protein carrier KLH. QS-21, or the related compound GPI-0100, was used as an adjuvant to enhance the immune response against the tumor-associated antigens present in the constructs. Initial ELISA investigations (data not shown) of the two potential conjugate vaccines indicated that construct 4 was superior to 3 from an immunological standpoint, and, consequently, 4 was thoroughly investigated. Remarkably, antibodies raised in response to 4 were not only able to identify the individual antigens in ELISAs but, as determined by FACS analysis, they also reacted strongly with tumor cells known to selectively express each tumor-associated antigen.

Numerous factors could influence the magnitude of the antibody response against individual antigens when more than one antigen is administered during vaccination. The combination of separate pathogen vaccines, such as diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis, hepatitis A, Haemophilus influenzae, type b tetanus toxoid conjugate, and inactivated poliomyelitis, generally results in similar antibody responses against the individual components, whether they are administered separately, simultaneously, or sequentially (34–36). Similarly, combining purified bacterial capsular polysaccharides does not seem to reduce the immunogenicity of the individual polysaccharide components. By contrast, for conjugate vaccines, several factors could potentially negatively impact the antibody response to individual antigens, especially when monomeric conjugate vaccines are combined and administered by using a mixture-like approach (37–45).

In some instances, exposure to a carrier appears to produce an amplified response on subsequent challenge, thereby resulting in increased antibody production against antigens conjugated to the same carrier protein (37, 38). In other cases, prior exposure to a carrier results in increased antibody levels only against the carrier and not to the conjugated antigens (39–41). Combining conjugate vaccines containing the same carrier, or simultaneous administration of the carrier in nonconjugated form, may result in a decreased antibody response against the target antigens (42–45). These complications could perhaps be avoided through combination of the various antigens on the same conjugate vaccine. Of course, it is possible that, on combining several antigens within the same construct, the immune response against one or more of the members of that set could be suppressed. Additionally, cross-reactivity involving more than one antigen might be observed, which would be expected to result in a portion of the antibody population produced having reduced affinity to particular antigens displayed on the cell surface. Significantly, our studies with compound 4 revealed that there was no substantial decrease in antibody titers over the course of immunizations with 4. Furthermore, no indication of an impaired antibody response against the individual antigens within the construct was apparent, as assessed by ELISA and FACS analysis. In fact, the antibody response for each individual antigen within the clustered construct was similar to that observed when the mixture of individual monomers was administered. What is even more significant, from a potential therapeutic point of view, is that, compared with the mixture of monomers, antibodies raised to the multivalent construct exhibited equal or higher reactivity with human cell lines expressing the native antigens, as determined by FACS analysis. Interestingly, although relatively high ELISA-based antibody titers were observed when sera resulting form vaccination with the polyvalent construct were screened against the polyvalent construct itself (see Table 1), FACS-based analyses (see Table 2) showed that that sera reacted just as well as sera derived form the monomers. The ELISA-based data in this case would seem to suggest that there was, indeed, cross-reactivity of antibodies between the antigens in the multivalent construct. However, the FACS data clearly indicate that this cross-reactivity does not negatively impact recognition of the antigens on the cell surface.

The lack of suppression of the antibody response against these multiantigenic vaccines may well be because of the KLH/adjuvant combination (7, 9, 10). The use of KLH as carrier and QS-21 as adjuvant has been shown to result in a potent helper T cell type 1 response (7). This is likely the case for GPI-0100 as well, given its close structural relationship to QS-21. We have previously shown that KLH is more effective as an immunogenic carrier than are a variety of other standard proteins. We have also demonstrated that for GD3-KLH and MUC1-KLH conjugates, adjuvants such as QS-21 induce a 1,000- to 100,000-fold augmentation of antibody responses in the mouse, compared with the use of the conjugates alone (9, 10). However, because our goal in the present study was primarily that of determining whether a multivalent conjugate vaccine could be administered without clear loss of immunogenicity against the individual components, we did not attempt to saturate the system.

Several other observations are noteworthy. Because GPI-0100 is less toxic than QS-21, greater quantities of GPI-0100 could be safely administered to the mice, and this resulted in a commensurate increase in antibody production. Also regarding antibody production, in general, compound 3 produced lower titers than compound 4. The structural differences between 3 and 4 may account for the immunological variance observed for these vaccines. Compound 3 is a more accurate mimic of mucin glycoproteins. Clustered glycoamino acids containing the mucin α-O-linked GalNAc core are highly rigidified, even in the case of very short glycopeptides, as a result of specific interactions between the gylcan and peptide backbone (20). Thus, as a result of such structurally based interactions, use of a mucin mimic that is faithful to the known architectural features of the cell surface molecule might impede the identification of the individual constituent antigens displayed on the peptide backbone during the immune response. In addition, the close resemblance of the structural core of the mucin-based vaccine construct (3) to self antigens within the mice, might make it more difficult to break tolerance.

We regard this study as providing an important proof of principle for the concept that single vaccine constructs, bearing several different carbohydrate antigens, have the potential to stimulate a multifaceted immune response necessary for optimal targeting of the heterogenous population of cells associated with a particular cancer type. Thus, because Globo-H, Ley, and Tn are each overexpressed on prostate cancer, vaccination with 4 could potentially induce a broader range of antibodies, which will have a greater likelihood of accomplishing immunosurveillance against a greater range of aberrant cells. It goes without saying that the scheme we have developed (24, 25) to reach these constructs is, in principle, readily adaptable to the inclusion of more complex patterns of glycosylation and more elaborate peptide motifs, which might activate other elements of the immune system. Such possibilities are being considered and pursued. The encouraging murine data described herein serve to support the case for initiating clinical trials with unimolecular multiantigenic vaccines of even greater immunodiversity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI-16943 and CA-28824 (to S.J.D.) and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation. D.M.C. gratefully acknowledges the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (PDF-230654-2000) and Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (199901330) for postdoctoral fellowship support. L.J.W. is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant F32-CA-79120. J.A. is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM-19578. C.H. is supported by American Cancer Society Grant PF-98-173001. P.W.G. is supported by American Cancer Society Grant PF-98026.

Abbreviations

- KLH

keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- FACS

fluorescence activated cell sorter

Footnotes

Slovin, S. F., Ragupathi, G., Olkiewicz, K., Tilak, J., Terry, K., Moore, M., Fazzari, J., Jakubowiak, J., Lu, L., Livingston, P. O., et al. (2000) Proc. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 41, 633 (abstr.).

Slovin, S. F., Ragupathi, G., Fernandez, C., Randall, E., Diani, M., Verbel, D., Bullock, A., Recaldez, E., Schwarz, J., Kuduk, S. D., et al. (2002) Proc. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 43, 560 (abstr.).

References

- 1.Zhang S, Cordon-Cardo C, Zhang H S, Reuter V E, Adluri S, Hamilton W B, Lloyd K O, Livingston P O. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:42–49. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970926)73:1<42::aid-ijc8>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang S, Zhang H S, Cordon-Cardo C, Reuter V E, Singhal A K, Lloyd K O, Livingston P O. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:50–56. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970926)73:1<50::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang H, Zhang S L, Cheung N V, Ragupathi G, Livingston P O. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2844–2849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Livingston P O. Sem Cancer Biol. 1995;6:357–366. doi: 10.1016/1044-579x(95)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Livingston P O, Ragupathi G. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1997;45:10–19. doi: 10.1007/s002620050395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danishefsky S J, Bilodeau M T. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1996;35:1380–1419. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helling F, Shang A, Calves M, Zhang S, Ren S, Yu R K, Oettgen H F, Livingston P O. Cancer Res. 1994;54:197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ragupathi G, Park T K, Zhang S, Kim I J, Graber L, Adluri S, Lloyd K O, Danishefsky S J, Livingston P O. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1997;36:125–128. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim S K, Ragupathi G, Musselli C, Choi S J, Park Y S, Livingston P O. Vaccine. 2000;18:597–603. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00316-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S, Ragupathi G, Cappello S, Kagan E, Livingston P O. Vaccine. 2000;19:530–537. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helling F, Zhang S, Shang A, Adluri S, Calves M, Koganty R, Longenecker B M, Yao T J, Oettgen H F, Livingston P O. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2783–2788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ragupathi G, Meyers M, Adluri S, Howard L, Musselli C, Livingston P O. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:659–666. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000301)85:5<659::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabbatini P J, Kudryashov V, Ragupathi G, Danishefsky S J, Livingston P O, Bornmann W G, Spassova M, Zatorski A, Spriggs D, Aghajanian C, et al. Int J Cancer. 2000;87:79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ragupathi G, Deshpande P P, Coltart D M, Kim H J, Williams L J, Danishefsky S J, Livingston P O. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:207–212. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickler M N, Ragupathi G, Liu N X, Musselli C, Martino D J, Miller V A, Kris M G, Brezicka F T, Livingston P O, Grant S C. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2773–2779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ragupathi G, Slovin S F, Adluri S, Sames D, Kim I J, Kim H M, Spassova M, Bornmann W G, Lloyd K O, Scher H I, et al. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1999;38:563–566. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990215)38:4<563::AID-ANIE563>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen J R, Ragupathi G, Livingston P O, Danishefsky S J. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:10875–10882. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilewski T, Ragupathi G, Bhuta S, Williams L J, Musselli C, Zhang X-F, Bencsath K P, Panageas K S, Chin J, Hudis C A, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3270–3275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051626298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slovin S F, Ragupathi G, Adluri S, Ungers G, Terry K, Kim S, Spassova M, Bornmann W G, Fazzari M, Dantis L, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5710–5715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coltart D M, Royyuru A K, Williams L J, Glunz P W, Sames D, Kuduk S D, Schwarz J B, Chen X-T, Danishefsky S J, Live D H. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9833–9844. doi: 10.1021/ja020208f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kensil C R, Patel U, Lennick M, Marciani D. J Immunol. 1991;146:431–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marciani D J, Press J B, Reynolds R C, Pathak A K, Pathak V, Gundy L E, Farmer J T, Koratich M S, May R D. Vaccine. 2000;18:3141–3151. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang S, Graeber L A, Helling F, Ragupathi G, Adluri S, Lloyd K O, Livingston P O. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3315–3319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams L J, Harris C R, Glunz P W, Danishefsky S J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:9505–9508. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen J R, Harris C A, Danishefsky S J. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:1890–1897. doi: 10.1021/ja002779i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lloyd K O, Kabat E A, Layug E J, Gruezo F. Biochemistry. 1966;5:1489–1501. doi: 10.1021/bi00869a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogata S, Chen A, Itzkowitz S H. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4036–4044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kudryashov V, Ragupathi G, Kim I J, Breimer M E, Danishefsky S J, Livingston P O, Lloyd K O. Glycoconjugate J. 1998;15:243–249. doi: 10.1023/a:1006992911709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hellstrom I, Garrigues H J, Garrigues U, Hellstrom K E. Cancer Res. 1990;50:2183–2190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eskola J, Kayhty H, Takala A K, Peltola H, Ronnberg P R, Kela E, Pekkanen E, McVerry P H, Makela P H. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1381–1387. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011153232004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneerrson R, Robbinson J B, Szu S C, Yang Y. In: Towards Better Carbohydrate Vaccines. Bell R, Torrigiani G, editors. London: Wiley; 1987. pp. 307–327. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donnelly J J, Deck R R, Liu M A. J Immunol. 1990;145:3071–3079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eskola J, Peltola H, Takala A K, Kayhty H, Hakulinen M, Karanko V, Kela E, Rekola P, Ronnberg P R, Samuelson J S. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:717–722. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198709173171201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones I G, Tyrrell H, Hill A, Horobin J M, Taylors B. Vaccine. 1988;16:113. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Usonis V, Bakasenas V, Williams P, Clemens R. Vaccine. 1997;15:1680–1686. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanra G, Silier T, Yurdakok K, Yavuz T, Baskan S, Ulukol B, Ceyhan M, Ozmert E, Turkay F, Pehlivan T. Vaccine. 2000;18:947–954. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00331-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson P. Infect Immun. 1983;39:233–238. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.1.233-238.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurika S. Vaccine. 1996;14:1239–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barington T, Gyhrs A, Kristensen K, Heilmann C. Infect Immun. 1994;62:9–14. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.9-14.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peters C C, Tenbergen-Meeks A M, Poolman J T, Beurret M, Zegers B J M, Rijkers G T. Infect Immun. 1974;59:3504–3510. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3504-3510.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarvas H, Makela O, Toivanen P, Toivanen A. Scand J Immunol. 1974;3:455–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1974.tb01278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fattom A, Cho Y H, Chu C, Fuller S, Fries L, Naso R. Vaccine. 1999;17:126–133. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barington T, Skettrup M, Juul L, Heilman C. Infect Immun. 1993;61:432–438. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.432-438.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cross A M, Artenstein A, Que J, Fredeking T, Furer E, Sadoff J C, Cryz S J., Jr J Infect Dis. 1994;170:834–840. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarnaik S, Kaplan J, Schiffman G, Bryla D, Robbins J B, Schneerson R. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1990;9:181–186. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199003000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]