Abstract

This study investigated both the activity of nisin Z, either encapsulated in liposomes or produced in situ by a mixed starter, against Listeria innocua, Lactococcus spp., and Lactobacillus casei subsp. casei and the distribution of nisin Z in a Cheddar cheese matrix. Nisin Z molecules were visualized using gold-labeled anti-nisin Z monoclonal antibodies and transmission electron microscopy (immune-TEM). Experimental Cheddar cheeses were made using a nisinogenic mixed starter culture, containing Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis UL 719 as the nisin producer and two nisin-tolerant lactococcal strains and L. casei subsp. casei as secondary flora, and ripened at 7°C for 6 months. In some trials, L. innocua was added to cheese milk at 105 to 106 CFU/ml. In 6-month-old cheeses, 90% of the initial activity of encapsulated nisin (280 ± 14 IU/g) was recovered, in contrast to only 12% for initial nisin activity produced in situ by the nisinogenic starter (300 ± 15 IU/g). During ripening, immune-TEM observations showed that encapsulated nisin was located mainly at the fat/casein interface and/or embedded in whey pockets while nisin produced by biovar diacetylactis UL 719 was uniformly distributed in the fresh cheese matrix but concentrated in the fat area as the cheeses aged. Cell membrane in lactococci appeared to be the main nisin target, while in L. casei subsp. casei and L. innocua, nisin was more commonly observed in the cytoplasm. Cell wall disruption and digestion and lysis vesicle formation were common observations among strains exposed to nisin. Immune-TEM observations suggest several modes of action for nisin Z, which may be genus and/or species specific and may include intracellular target-specific activity. It was concluded that nisin-containing liposomes can provide a powerful tool to improve nisin stability and availability in the cheese matrix.

Several Lactococcus lactis strains produce nisin, a 3.4-kDa antimicrobial peptide composed of 34 amino acids, which include unsaturated amino acids and lanthionine residues. Two natural variants of nisin, A and Z, are equally distributed among nisin-producing strains and differ by a single amino acid substitution at position 27, histidine in nisin A and asparagine in nisin Z (26, 50). Nisin inhibits a wide variety of gram-positive bacteria and has GRAS (generally recognized as safe) status; it therefore is used as a preservative in various food products (23, 24).

The generally accepted mode of action of nisin on vegetative cells involves the formation of pores in the cytoplasmic membrane of target cells by the barrel-stave mechanism (51) and/or wedge model (27). This leads to the efflux of essential small cytoplasmic components, such as amino acids, potassium ions, and ATP (4, 54, 63). However, several in vivo observations remain enigmatic. For example, the striking differences in sensitivity often observed among different strains of the same bacterial species (55) have not yet been explained, and cell membrane composition seems to play a crucial role in this respect (15, 44, 52, 57, 61). The association of nisin with the cell membrane is largely dependent on the type of lipids present and especially on their charge (43). Several studies have demonstrated that due to the cationic nature of nisin, its activity in vitro is most efficient in the presence of a high percentage of anionic, negatively charged membrane lipids (12, 40). It is conceivable, however, that in vivo interactions of nisin with unidentified molecules may be important for membrane disruption and killing (55). Characterization of distinct structure-activity relationships for various antibacterial activities of nisin would provide a valuable tool in further mechanistic investigations (17).

Nisin activity has been studied in gram-positive bacteria of concern in foods with an extended shelf life, such as Listeria monocytogenes (2, 18). However, nisin is commonly added directly to food systems in the form of commercial products to inhibit Listeria contamination, an application in which activity loss occurs over time because of enzymatic degradation and interactions with food components such as proteins and lipids (34). For these reasons, in our previous study we developed and optimized an encapsulation process for nisin in liposomes prepared from proliposome H (R. Laridi, E. E. Kheadr, R.-O. Benech, J. C. Vuillemard, C. Lacroix, and I. Fliss, submitted for publication). In that study, anti-nisin Z monoclonal antibodies were used to quantify the encapsulated nisin via a competitive enzyme immunoassay method and to visualize encapsulated nisin molecules by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The main advantages of liposome H were 47% higher entrapment efficiency and lower susceptibility to destabilization by nisin. The system was used in Cheddar cheese manufacture to inhibit Listeria innocua and was compared to the use of nisin produced in situ by a nisinogenic starter culture (3). Over a 6-month cheese-ripening period, encapsulated nisin proved to be more active at inhibiting L. innocua and much more stable compared to in situ-produced nisin.

Our aim in the present study was to use anti-nisin Z antibodies and transmission electron microscopy to (i) gain insight into the antibacterial effects of nisin Z against bacterial cells belonging to three different species (Listeria, Lactococcus, and Lactobacillus) in complex media such as Cheddar cheese and (ii) visualize the distribution of both encapsulated and in situ-produced nisin Z in a Cheddar cheese matrix, in order to better understand the differences in the availability, stability, and efficacy of each form of nisin Z.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and growth conditions.

Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis UL 719 was used as the nisin Z producing strain (45). Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris KB and Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis KB were obtained from Ezal, Rhône Poulenc, Mississauga, Canada). Listeria innocua (ATCC 33090) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.), and Lactobacillus casei subsp. casei L2A was obtained from the Food Research Institute (Agriculture and Agrifood Canada, Ottawa, Canada). Pediococcus acidilactici UL5, from our collection, was used as the indicator organism for the bacteriocin activity assay (8).

All bacterial cultures were maintained in 20% glycerol stock at −80°C. Lactococcus strains were grown in M17 broth medium (BDH-Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose and incubated overnight at 30°C (59). Biovar diacetylactis UL 719 was cultivated in MRS broth (25) obtained from Rosell Institute Inc. (Montreal, Canada) and incubated overnight at 30°C. L. innocua was reactivated in tryptic soy broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C. L. casei subsp. casei was reactivated in MRS broth and incubated anaerobically in Oxoid jars by using an atmosphere generation system (anaeroGenTM; Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, England) at 37°C. Before the experiments, each bacterial strain was subcultured at least three times (1%, vol/vol) into the indicated media at 24-h intervals.

Nisin Z production and purification.

Nisin Z was extracted from an overnight MRS culture of biovar diacetylactis UL 719 and purified using an immunoaffinity column developed in our laboratory as previously described (3). Nisin Z activity, determined by agar diffusion and competitive enzyme immunoassay, and of nisin Z purity, tested with high-performance liquid chromatography, were evaluated by methods described previously (22).

Liposome preparation.

Liposomes were prepared from proliposome H (Pro-lipo H) made of food-grade hydrogenated phosphatidylcholine obtained from Lucas Meyer (Chelles, France). For cheese production, 5 g of Pro-lipo H was converted to liposomes by mixing with 5 ml of aqueous nisin solution (5 mg/ml). The formed vesicles were separated from unencapsulated nisin, washed, and resuspended in deionized water by the procedure previously described (Laridi et al., submitted). The amount of encapsulated and unencapsulated nisin was determined using competitive enzyme immunoassay and agar diffusion methods (22).

Cheese-making procedure.

A cheese starter composed of L. lactis subsp. lactis (KB) and L. lactis subsp. cremoris (KB) cultures at a ratio of 1:1 (vol/vol) was previously optimized and selected for its high acidifying capacity and nisin Z tolerance (3). Starter bacteria were added to cheese milk at a level of 5.0 × 106 to 1.0 × 107 CFU/ml. The nisin-producing mixed starter composed of cheese starter and biovar diacetylactis UL 719 at a ratio of 3:1 (vol/vol) was added to cheese milk at a level of 107 to 108 CFU/ml. In trials concerning its use as a member of the cheese secondary flora, L. casei subsp. casei L2A was added to cheese milk at a level of 103 to 104 CFU/ml simultaneously with the cheese mixed culture. For cheese production, Lactococcus strains and L. casei subsp. casei were grown separately in sterilized reconstituted skim milk (11% total solids) and incubated overnight at 30 and 37°C, respectively. An overnight tryptic soy broth culture of L. innocua was used to inoculate cheese milk at a concentration of 105 to 106 CFU/ml. The experimental cheeses and their codes are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Cheese treatments used in this study

| Cheese codea | Presence of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biovar diacetylactis UL 719b | L. innocua | Encapsulated nisin Zc | L. casei subsp. casei L2A | |

| 35 | − | − | − | − |

| 35B | − | − | − | + |

| 35L | − | + | − | − |

| 358 | + | − | − | − |

| 358B | + | − | − | + |

| 358L | + | + | − | − |

| 35BL | − | − | + | + |

All cheeses were made using a 1:1 (vol/vol) mixed starter culture of L. lactis subsp. lactis (KB) and L. lactis subsp. cremoris (KB), with L. casei L2A (B) added at 103 to 104 CFU/ml or not added.

Nisin Z-producing strain.

Encapsulated-nisin liposomes were produced by diluting 5 g of proliposome H with 5 ml of nisin Z aqueous solution at 5 mg/ml. Following separation of liposomes, the resulting vesicles were added to 10 liters of cheese milk for a final concentration of 300 IU/g of cheese.

Prior to cheese-making, cheese milk was standardized to a constant fat content of 3.4%, pasteurized at 72°C for 16 s, and cooled to 4°C. Ten-liter batches of milk were warmed to 32°C and inoculated with the selected cheese starter mixed culture at 1.5% (vol/vol) for Cheddar cheese production by the standard procedure described previously (37). For encapsulated-nisin Cheddar cheese production, the nisin-containing liposome preparation was added just before the renneting step. At the end of production, the cheese was cut and a representative sample of approximately 200 g was taken for analyses. Cheese blocks were then vacuum packed in plastic bags (4 mm thick; Winpax Co., Winnipeg, Canada), coded, and ripened at 7°C for 6 months.

Cheese analyses.

For microbiological analyses, cheese samples (10 g) were homogenized with 90 ml of sterile 2% sodium citrate solution for 3 min in a Stomacher (Lab Blender 80; Seward Medical, London, England), as described previously (33). The cheese samples were then serially diluted 10-fold in 2% sodium citrate. Appropriate dilutions were plated on lactococcus-selective medium, Kempler and McKay agar (KMK), and incubated aerobically at 37°C for 24 h to enumerate lactococci in cheeses (35). L. casei subsp. casei was enumerated by plating appropriate dilutions on acidified MRS agar (pH 5.6) and incubating anaerobically at 37°C for 72 h. L. innocua was counted on Listeria selective agar base (Oxoid) with selective supplement SR140E (200 mg of cycloheximide, 10 mg of colistin sulfate, 5 mg of fosfomycin, 2.5 mg of acriflavin, and 1 mg of cefotan per 500 ml of medium) and incubated at 37°C for 48 h.

Nisin Z extraction from cheese matrix and the agar diffusion test used to estimate nisin activity were performed as previously described (3).

TEM.

Cheese cubes (0.8 to 1.0 mm) were fixed overnight at 4°C in 0.05% (wt/vol) glutaraldehyde-2.5% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2). They were then washed four times (10 min each) with sodium cacodylate buffer and postfixed for 2 h at 4°C in 1% (wt/vol) osmium tetroxide. After being washed four more times with sodium cacodylate buffer, the samples were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, embedded in Quetol (Marivac, Halifax, Canada), and polymerized at 60°C for 24 h (1). Ultrathin sections (0.1 μm) of samples were cut with an ultramicrotome (Reichert-Jung, Vienna, Austria) and collected on Formvar-coated nickel grids (JBEM, Dorval, Canada). For the immunological reaction, the grids were incubated for 20 min in 3% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (Sigma) and then for 1 h at room temperature with 1/50 (vol/vol) anti-nisin Z monoclonal antibodies (2 mg of protein/ml) produced in mice (22). The grids were then washed six times (10 min each) in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.3) containing 0.05% (wt/vol) Tween 80. Gold labeling was carried out by incubating the grids for 30 min at room temperature with protein A-colloidal gold (10 or 20 nm in diameter; Sigma) diluted 1/10 in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.2% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 20000. The grids were washed again as described above, dried, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined with a 1200 EX microscope (JEOL, Peabody, Mass.) at 80 kV. For each cheese sample, 10 to 15 fields from five to seven ultrathin sections resulting from three grids were examined, and the photographs presented in this study represent a general observation taken through the tested grids.

Statistical analysis.

All cheeses were made from the same lot of milk. Each cheese type was produced in triplicate, and all analyses were done in duplicate. Statistical analyses were performed with Stat View SE + Graphics (Abacus Concepts Inc., Berkeley, Calif.). Significant differences between treatments were tested by analysis of variance. Treatment comparisons were performed using Fisher's protected least significant differences (PLSD) test, with a level of significance of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Bacterial populations in Cheddar cheeses during storage.

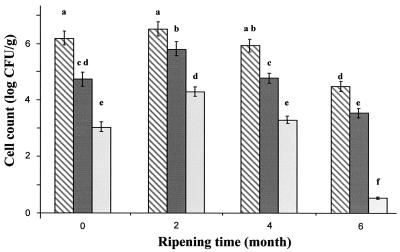

The effect of the nisin-producing strain and encapsulated nisin on the viable count of L. innocua during cheese ripening is illustrated in Fig. 1. Encapsulated nisin Z was more effective at reducing L. innocua viability than was the nisin-producing strain. This effect was noticeable from the day of production and continued until the end of the ripening period. At the beginning of ripening, about 3- and 1.5-log cycle reductions in the L. innocua viable count were measured in cheeses made with encapsulated nisin and the nisin-producing strain, respectively. The viable counts of L. innocua in 6-month-old liposome-containing cheese were below the detection limit of the method (10 CFU/g), compared to approximately 3.5 × 103 ± 0.3 × 103 CFU/g in cheeses with added biovar diacetylactis UL 719 and 3.2 × 104 ± 0.3 × 104 CFU/g for control cheeses.

FIG. 1.

Changes in L. innocua viable-cell counts during ripening of Cheddar cheeses. Results for nisin-free cheese (hatched bars) (control treatment 35L), cheeses with the added nisin Z-producing strain (dark bars) (treatment 358L), and cheeses with encapsulated nisin Z (light bars) (treatment 35LL) are shown. Columns with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05).

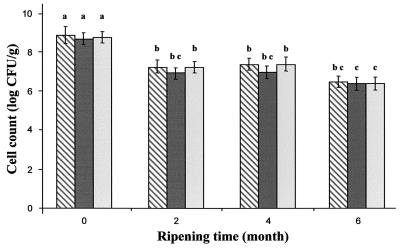

Figure 2 shows a gradual decrease in the viable count of Lactococcus cells observed in control and experimental cheeses during ripening. For an equal number of Lactococcus cells (P > 0.05) at the beginning of ripening, the viable counts of lactococci in control and experimental cheeses were not statistically different (P > 0.05) throughout the 6 months of storage. With aging, there was a gradual decrease in the viability of lactococci, from 6.4 × 108 ± 0.6 × 108 CFU/g after production to 2.7 × 106 ± 0.3 × 106 CFU/g after 6 months, with no significant differences between control and experimental cheeses.

FIG. 2.

Changes in Lactococcus viable-cell counts during ripening of Cheddar cheeses. Results for nisin-free cheese (hatched bars) (control treatment 35B), cheeses with the added nisin Z-producing strain (dark bars) (treatment 358B), and cheeses with encapsulated nisin Z (light bars) (treatment 35BL) are shown. Columns with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05).

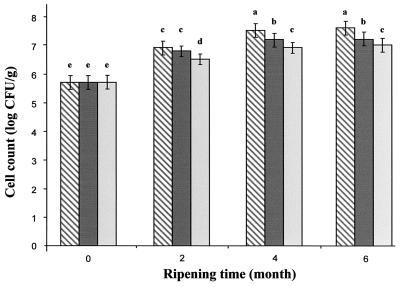

Nisin Z, either encapsulated or produced in situ by biovar diacetylactis UL 719, appeared to affect the L. casei subsp. casei viable count (Fig. 3). The initial viable count of L. casei subsp. casei was similar in all cheeses (P > 0.05) and increased gradually with increasing ripening time. At 2 to 6 months of ripening, experimental cheeses subjected to treatments with added biovar diacetylactis UL 719 (358B cheese) or liposome-containing nisin (35BL cheese) gave viable L. casei subsp. casei counts 0.2 and 0.5 log CFU/g lower than did the control cheese (35B cheese), respectively. In 6-month-old cheeses, the viable counts of L. casei subsp. casei were above 7 log CFU/g and the counts in cheeses with added liposomes or biovar diacetylactis UL 719 remained significantly lower than those in the control cheese (35B cheese), by 0.5 and 0.2 log CFU/g, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Changes in L. casei subsp. casei L2A viable-cell counts during ripening of Cheddar cheeses. Results for nisin-free cheese (hatched bars) (control treatment 35B), cheeses with the added nisin Z-producing strain (dark bars) (treatment 358B), and cheeses with encapsulated nisin Z (light bars) (treatment 35BL) are shown. Columns with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Antibacterial activities of nisin Z in the Cheddar cheese matrix.

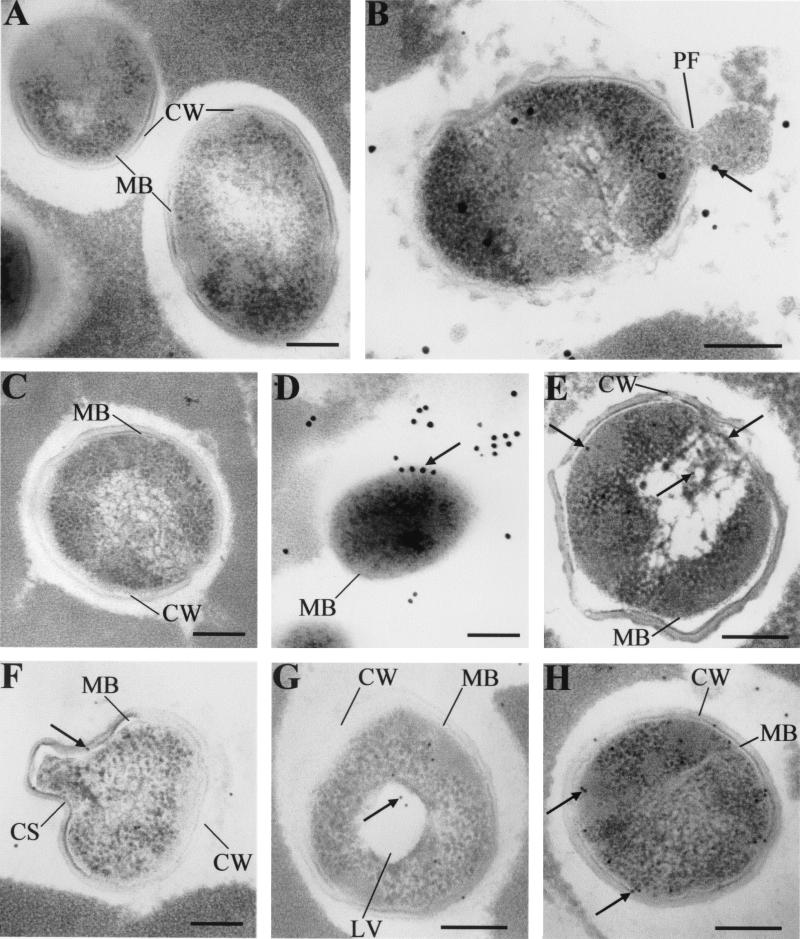

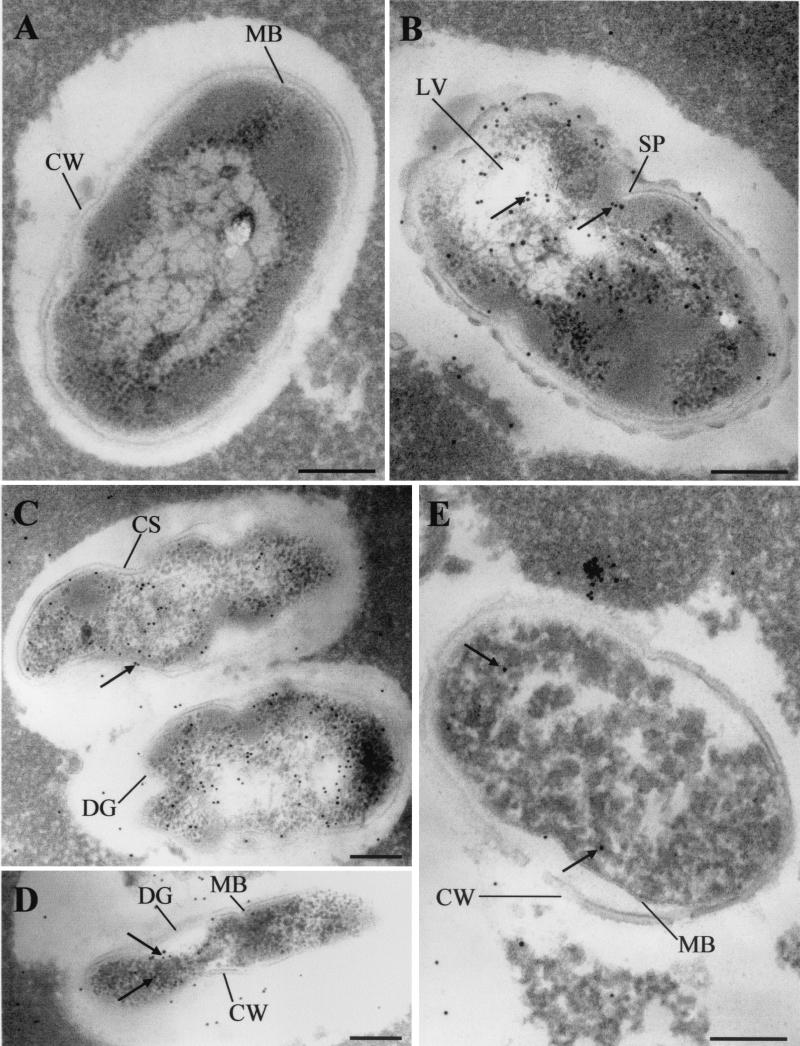

To observe the antibacterial activity of nisin against different bacteria in Cheddar cheese matrices, anti-nisin Z monoclonal antibodies and protein A-gold conjugate coupled with TEM were used. Although the starter mixture used in this study was previously selected for its tolerance to nisin Z (3), TEM observations revealed that some lactococcal subpopulations had become sensitive to nisin Z in both cheeses with added biovar diacetylactis UL 719 and those with encapsulated nisin Z. In the nisin-sensitive lactococcal population, cytoplasmic membrane appeared to be the principal nisin target. At the beginning of ripening, pore formation in the cell membrane followed by leakage of intracellular compounds seemed to be the predominant effect of nisin on the sensitive lactococcal population (Fig. 4B). In 30-day-old cheeses, some lactococcal cells had lost their cell wall and gold-labeled antibodies to nisin were detected on the cytoplasmic membrane surface (Fig. 4D). Nisin also affected cell morphology through the formation of curved surface in the cell wall (Fig. 4F). Cell wall thickness appeared to increase in nisin-sensitive cells (Fig. 4E to G). The formation of lysis vesicles is another effect of nisin that was observed in fresh cheese samples (Fig. 4G). Some lactococcal cells in cheeses with added biovar diacetylactis UL 719 showed a heavy concentration of gold-labeled antibodies to nisin on the inner side of their cytoplasmic membrane while maintaining cell wall and membrane integrity (Fig. 4H), which may correspond to biovar diacetylactis UL 719 cells.

FIG. 4.

Transmission electron micrographs of effects of nisin Z on the nisin-sensitive Lactococcus population during ripening of experimental Cheddar cheeses. (A, B, F, G, and H) Fresh cheeses; (D and E) One- and 6-month-old cheeses, respectively. (A) Nisin-free cheese (35 cheese) as negative control; (C) cheese with biovar diacetylactis UL 719 (358 cheese) as positive control for immune reaction; (B, C, D and E) cheeses with added biovar diacetylactis UL 719; (F and G) cheeses with encapsulated nisin. Nisin was visualized using monoclonal anti-nisin Z, protein A-colloidal gold conjugate (arrows). Colloidal gold 10 nm (E, F, G, and H) or 20 nm (B and D) in diameter was used to visualize nisin-antibody complexes. Symbols: CW, cell wall; MB, cell membrane; PF, pore formation; CS, curved surface; LV, lysis vesicle. The grids were examined at 80 kV. Magnifications, ×37,600 (A, C, D, and F), ×47,000 (E, G, and H) and ×56,400 (B). Bars, 200 nm.

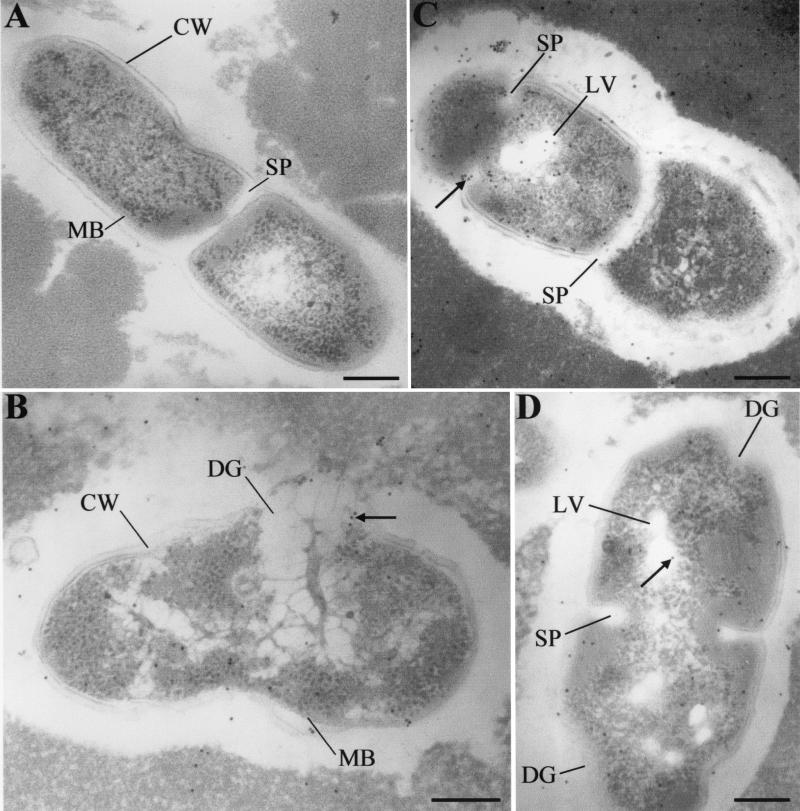

The action of nisin Z, either encapsulated or produced by biovar diacetylactis UL 719, on L. casei subsp. casei could be visualized after 1 month of ripening. After production, a limited effect of nisin was observed, as expected, due to the nisin tolerance characteristic of the selected strain of L. casei subsp. casei. The major inhibitory effect of nisin on the day of manufacture was principally against cells at the division phase, with the induction of vesicle lysis in intact cells being the predominant nisin effect (Fig. 5B). Cytoplasm in L. casei subsp. casei cells appeared to be the preferential nisin site since many gold-labeled antibodies to nisin were observed entrapped in the cytoplasm of cells with an intact cell wall and membrane. After 1 month of ripening, the effect of nisin on lactobacilli became more evident (Fig. 5C), with formation of curved cell walls as the predominant effect of nisin on the nisin-sensitive L. casei subsp. casei population (Fig. 5C and D). The cell wall thickness appeared to increase in nisin-sensitive cells (Fig. 5C and D). The formation of the curved cell wall, partial digestion (Fig. 5C) or disappearance (Fig. 5E) of the cell wall, and reduction in the cytoplasmic volume (Fig. 5D) were all the predominant inhibitory effects of nisin against L. casei subsp. casei cells.

FIG. 5.

Effect of nisin Z on L. casei subsp. casei L2A in fresh (B), 1-month-old (C and D), and 6-month-old (E) Cheddar cheeses made with a mixed culture containing biovar diacetylactis UL 719. Nisin-free cheese (35B cheese) was used as a negative control (A). Arrows indicate the complex between nisin Z, anti-nisin Z monoclonal antibodies, and protein A-colloidal gold conjugate (10-nm-diameter gold). Symbols: CW, cell wall; MB, cell membrane; CS, curved surface; LV, lysis vesicle; SP, septum; DG, digested area. The grids were examined at 80 kV. Magnifications, ×37,600 (D and E) and ×47,000 (A to C). Bars, 200 nm.

The inhibitory action of nisin Z against L. innocua was evident from the first day of cheese production (Fig. 6B). L. innocua showed a higher sensitivity to nisin Z than did the lactococci and L. casei subsp. casei. As mentioned above, L. innocua counts dropped by 1.5 and 3 log CFU/g in fresh cheeses with added biovar diacetylactis UL 719 or liposome-containing nisin Z, respectively. Similarly to L. casei subsp. casei, the cytoplasm appeared to be the preferred site for nisin molecule localization, since many gold-labeled antibodies to nisin were detected inside L. innocua cells with no disturbance of cell wall or cell membrane organization (Fig. 6C). The main action of nisin Z at the beginning of ripening was indicated by the presence of degraded, partially digested cell walls (Fig. 6B) and induction of lysis vesicle formation. These effects remained observable over the entire ripening period (Fig. 6D). Nisin Z also appeared to disturb or disorder some physiological process in L. innocua as the ripening time progressed. During the first month of ripening, disorder in cell division became apparent (Fig. 6C) and predominated over cell wall digestion and autolysis induction.

FIG. 6.

Effect of nisin Z on L. innocua in fresh (A and B), 1-month-old (C), and 6-month-old (D) Cheddar cheeses. (A) Nisin-free L. innocua-containing cheese (35L cheese); (D) cheese made with mixed culture containing biovar diacetylactis UL 719 (358L cheese); (B and C) cheeses made with encapsulated nisin Z (35LL cheese). Arrows indicate the complex between nisin Z, anti-nisin Z monoclonal antibodies, and protein A-colloidal gold conjugate (10-nm-diameter gold). Symbols: CW, cell wall; MB, cell membrane; LV, lysis vesicle; SC, curved surface; SP, septum; DG, digested area. The grids were examined at 80 KV. Magnifications, ×37,200 (A, C, and D) and ×46,500 (B). Bars, 200 nm.

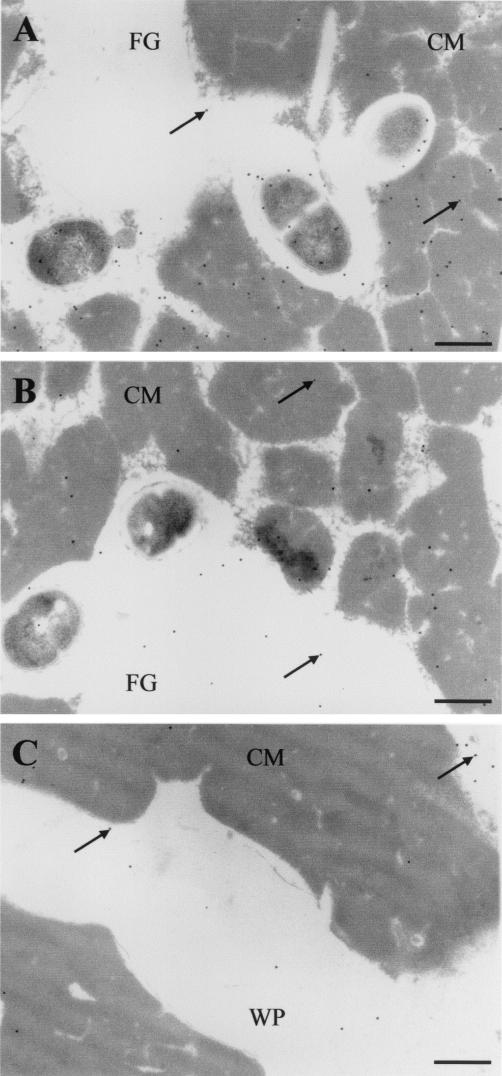

Nisin Z localization in the cheese matrix.

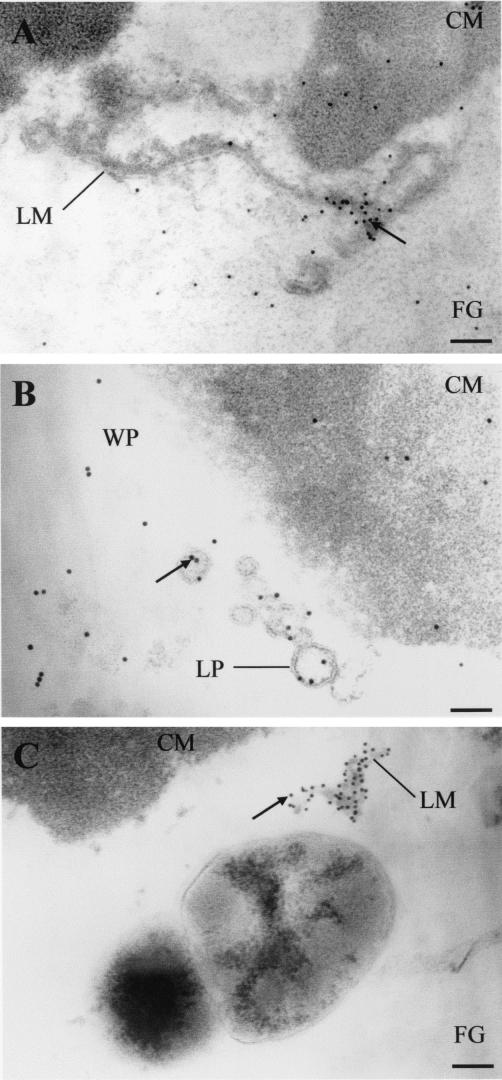

At the beginning of ripening, nisin produced by the nisinogenic strain was uniformly distributed through the cheese matrix (Fig. 7A and B). However, in cheeses with added encapsulated nisin, the majority of nisin molecules were confined to the fat/casein interface and in residual whey pockets, where liposomes were principally located, while few gold-labeled antibodies to nisin were seen embedded in casein or lipid phases (Fig. 7C). In 6-month-old cheeses with added biovar diacetylactis UL 719, the signals of gold-labeled antibodies to nisin became less dense compared to those in 0-day-old cheese (data not shown), as well as more concentrated in the fat phase. The 6-month-old cheeses with added encapsulated nisin showed more dense signals of gold-labeled antibodies to nisin than those observed in 6-month-old cheeses with added biovar diacetylactis UL 719. Encapsulated nisin in 6-month-old cheeses appeared to be located at the fat/casein interface, and signals of gold-labeled antibodies to nisin in the fat phase became more dense than in 0-day-old cheese but less dense than in cheeses with added biovar diacetylactis UL 719.

FIG. 7.

Nisin Z distribution in fresh Cheddar cheese matrix. (A and B) Cheeses made with mixed culture containing biovar diacetylactis UL 719; (C) cheese made with encapsulated nisin Z. Arrows indicate the complex between nisin Z, anti-nisin Z monoclonal antibodies, and anti-protein A-colloidal gold conjugate (10-nm-diameter gold). Symbols: CM, casein matrix; FG, fat globules; WP, whey pocket. The grids were examined at 80 kV. Magnification, ×13,950. Bars, 500 nm.

Nisin Z activity in Cheddar cheese.

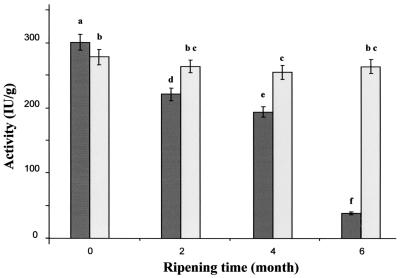

The biological activity of nisin Z in cheeses with liposomes or nisinogenic starter during ripening is shown in Fig. 8. Following cheese production, nisin activity in cheese with biovar diacetylactis UL 719 was 300 ± 15 IU/g versus 280 ± 14 IU/g for liposome-containing cheeses. During ripening, there was a progressive decline in nisin Z activity in cheeses with added biovar diacetylactis UL 719 to 35 ± 2 IU/g after 6 months, corresponding to 12% of the initial nisin activity. In liposome-containing cheeses, the activity of nisin Z was slightly reduced during the second month of ripening, to 260 ± 13 IU/g, representing 92% of the initial nisinogenic activity. Thereafter, no significant degradation was observed throughout the ripening period.

FIG. 8.

Changes in nisin Z activity during ripening of Cheddar cheeses made with nisin Z-producing culture (dark bars) (treatment 358L) or encapsulated nisin Z (light bars) (treatment 35LL). Means within the same column without a common letter are significantly different (P < 0.05) in the PLSD test.

Immune-TEM observation of nisin Z-containing liposomes.

Intact liposome vesicles with gold-labeled antibodies to nisin could be observed in the residual whey pockets even after 1 month of ripening (Fig. 9B). Many gold-labeled antibodies to nisin were observed along the inner surface of the liposomal membrane of small unilamellar vesicles in the diameter range of 80 to 120 nm. Large unilamellar vesicles were less stable, and many appeared as linear or unilamellar structures even in cheese samples analyzed immediately after production (Fig. 9A). In addition, linear liposome structures with strong signals of gold-labeled antibodies to nisin could be observed at the fat/casein interface throughout the ripening period (Fig. 9C).

FIG. 9.

Transmission electron micrographs of nisin Z encapsulation and immobilization in the liposome membrane during ripening of Cheddar cheese matrix. (A) Fresh cheese; (B) 1-month-old 35BL cheese; (C) 6-month-old 35BL cheese. Arrows indicate the complex between nisin Z, anti-nisin Z monoclonal antibodies, and anti-protein A-colloidal gold conjugate (10-nm-diameter gold). Symbols: CM, casein matrix; WP, whey pocket; FG, fat globules; LP, liposome vesicle; LM, liposome membrane. The grids were examined at 80 kV. Magnification, ×46,500. Bar, 100 nm.

DISCUSSION

Our previous study has shown the necessity for careful selection of the starter culture to be incorporated with nisin-producing strains for Cheddar cheese manufacture in order to avoid delayed acidification and to maximize nisin Z production (3). We also demonstrated the effectiveness of liposome-entrapped nisin Z at inhibiting L. innocua in Cheddar cheese compared to that of nisin Z-producing biovar diacetylactis UL 719. In the present study, we used immune-TEM to characterize nisin Z distribution in the Cheddar cheese matrix and its antibacterial action against nisin-sensitive populations of lactococci, L. casei subsp. casei, and L. innocua. This method may help us to better understand the antibacterial action of nisin Z, the higher stability of encapsulated nisin, and the role that could be played by liposome-immobilized nisin Z in improving cheese quality.

As observed, encapsulated nisin was much more effective at inhibiting L. innocua than was the nisin Z-producing strain for a similar initial concentration of about 300 IU/g of cheese. This effect increased with the ripening time and was correlated with a high activity and stability of encapsulated nisin compared to that produced by the nisinogenic strain. This observation was first reported in our previous work (3) demonstrating the stability and availability of encapsulated nisin to inhibit L. innocua in cheese. As expected, the viable counts of lactococci did not differ significantly between treatments over the 6 months of ripening, due to the high nisin tolerance of the selected strains. On the other hand, nisin Z did appear to limit the growth of L. casei subsp. casei during ripening, in contrast to its negligible effect on lactococci, which declined in number similarly for all treatments. The growth-limiting effect was already apparent at 2 months with encapsulated nisin, and the magnitude of this effect remained constant for the rest of the ripening period.

Immune-TEM observations carried out during the 6 months of cheese ripening provided evidence of differing responses among the bacterial groups to nisin Z. Nisin Z appeared to act differently on lactococci, L. casei subsp. casei, and L. innocua, indicating the possible existence of several biological actions. Cell membrane disorganization leading to pore formation was much more pronounced in lactococci than in L. casei subsp. casei and L. innocua. The difference in response to nisin Z may be attributed to differences in cell membrane composition, which may increase the affinity of nisin to certain bacterial cells. Cell membrane composition plays a distinct role in determining cell sensitivity to nisin. Nisin Z-resistant strains of Listeria monocytogenes contain more zwitterionic than anionic phospholipids in their membrane, in contrast to nisin Z-sensitive strains (18). Ming and Daeschel (46) found that nisin-resistant mutants of L. monocytogenes contained a greater proportion of straight-chain fatty acids whereas the parent strain contained more branched-chain fatty acids, and no changes in instauration of lipid acyl chains were reported. On the other hand, nisin Z can use the lipid-bound cell wall precursor lipid II as a docking molecule for subsequent pore formation (62). Breukink et al. (13) attributed the diverse sensitivities to nisin displayed by different bacteria to the differences in lipid II concentrations in their membranes. They also reported that the nisin-lipid II interaction increased with increasing lipid II concentration from 0.001 to 0.1 mol%.

Pore formation in the cell membrane is generally recognized to be the principal mechanism of action of nisin (55). Depolarization of the cell cytoplasmic membrane followed by the efflux of small cytoplasmic components such as amino acids, potassium ions, and ATP led to an instant cessation of all biosynthetic processes (32, 39, 60). Nisin Z causes an immediate loss of cell K+, phosphate, and ATP in L. monocytogenes, suggesting the unselectivity of these pores (2). In addition, the bactericidal effect of nisin through pore formation has been found to be an energy- and transmembrane electrical potential-dependent process in the absence of lipid II (47, 54, 62). When lipid II is available, nisin can disturb the barrier function of membrane at nanomolar concentrations, compared to micromolar range without lipid II (62).

For both L. casei subsp. casei and L. innocua, immunomarking and TEM showed that the cell wall may play an important role in nisin Z action. Cell wall disruption and digestion were the predominant actions of nisin Z against these bacteria. It is known that nisin interferes with cell wall biosynthesis by complexing with lipid II (52). However, it has been recently reported that lipid II may be helpful, although not essential, in the formation of pores (14). At high nisin concentrations (micromolar range), pores can be formed without lipid II, in a target-independent fashion (62). Other, studies have suggested that nisin induces the activity of cell wall hydrolases such as amidases, which may be potential targets for nisin (6, 41, 57). Nisin may release the enzymes from their cell wall-intrinsic inhibitors, the teichoic and teichuronic acids, leading to an apparent activation of cell wall hydrolases and induction of autolysis (7). Nisin and Pep 5, a bacteriocin produced by Staphylococcus epidermidis, activate Staphylococcus simulans N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase and β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (7). Nisin also promotes the activity of autolysins and peptidoglycan hydrolases, which are capable of causing bacterial autolysis. It has been recently demonstrated that nisin and lactococcins act synergistically with autolysins on bacterial lysis (42). The authors reported that AcmA autolysin-deficient L. lactis subsp. lactis MG 1363 did not lyse when incubated with nisin or a mixture of lactococcins A, B, and M, in contrast to the parent strain. Bacteriocins did not appear to activate autolysis, but they promoted uncontrolled cell wall degradation of AcmA autolysin (42).

On the other hand, as a general observation in this study, nisin Z was preferentially localized in the cytoplasm of L. casei subsp. casei and L. innocua cells, which kept their cell membrane integrity. Models proposed for the antibacterial action of nisin on target cells assume the aggregation of several nisin molecules prior to pore formation (27, 55). However, our study suggests that the passage of individual nisin molecules might not damage the cell membrane. Another explanation for intense signals of gold-labeled antibodies to nisin in the cytoplasm may be the transitory character of the pore opening as previously proposed for nisin A and nisin Z (2, 5, 49). In experiments using an artificial phospholipid membrane, nisin has been shown to induce transmembrane movements, indicating a transient disturbance of the phospholipid organization (49). The transitory character of pore opening by nisin Z has been observed by using intact cells of L. monocytogenes Scott A, in which ATP efflux was stopped 1 min after nisin Z addition (2).

Induction of lysis vesicle formation was a common observation in our tested bacteria. The formation of these vesicles was shown to be independent of the cell wall- and membrane-damaging effects of nisin, since many lysis vesicle-containing cells with intact cell walls and membranes were seen, which may indicate that nisin Z acts on specific intracellular targets. Induction of proteolytic enzyme production, metabolic disorder, and decreased respiratory function may all be potential internal effects for nisin Z (31, 55).

Another observed action of nisin Z is the formation of a curved cell membrane. This effect seems to be the first step in pore formation. It has recently been reported that nisin induces the formation of structures involving curved lipid planes (inverted hexagonal and cubic phases) with unsaturated phosphatidylethanolamines (29), and this morphological change may be due to a shift in the amphiphilic balance caused by the penetration of the peptide into the lipid assemblies (39). Results obtained with lipid membrane models indicate that distortion of the vesicular structure of lipid membranes by nisin leads to a drastic alteration of membrane integrity, which could be a possible contribution to the antibacterial mechanism of nisin (30).

The characterization of nisin Z distribution in the Cheddar cheese matrix could be useful for better understanding the stability, availability, and effectiveness of both forms of nisin (encapsulated or produced by nisinogenic strains). The distributions of liposome-encapsulated nisin and nisin produced by biovar diacetylatis UL 719 were quite different, possibly as a result of the difference in the distribution of biovar diacetylactis UL 719 and liposome vesicles throughout the cheese matrix. The fat/casein interface and residual whey pockets were the primary sites of liposome location. The localization of liposomes at the fat/casein interface has been reported in other studies and has been tentatively explained by the interactions between liposomes and fat globule membranes (36, 38). On the other hand, the formation of nonlamellar membrane structures with immobilized nisin Z might ensure the presence of nisin Z at those sites during ripening and reduce its affinity for the lipid phase. This could explain the weak signals of gold-labeled antibodies to nisin in the lipid phase of cheeses with added encapsulated nisin compared to those with biovar diacetylactis UL 719. The stronger concentration of gold-labeled antibodies to nisin in the fat phase as cheeses aged has been reported for Gouda cheese made with a mixed culture containing biovar diacetylactis UL 719, indicating the lower accessibility and availability of nisin Z produced by the nisinogenic mixed starter culture (9). On ripening, the fat globule membranes are disrupted, leading to the coalescence of fat globules and the formation of large fat aggregates to which free nisin molecules may bind via their hydrophobic N-terminal portion.

Our findings concerning the higher activity and stability of encapsulated nisin Z compared to biovar diacetylactis UL 719-produced nisin in ripening cheese are in accordance with those reported in our previous work (3). The decline in nisin activity in 6-month-old cheeses containing biovar diacetylactis UL 719 was equal to 88% of the initial activity in 0-day-old cheeses. This decline may result partly from the association of nisin molecules with the fat phase during ripening, as discussed above. In comparison, 90% of the initial nisinogenic activity was detected in 6-month-old cheeses containing encapsulated nisin, indicating the role that liposomal membranes may play in improving nisin stability and availability. TEM showed that the nonlamellar membrane structure was the predominant form for liposome membranes during the ripening period compared to lamellar structured membranes. The nonlamellar form may be responsible for improving the activity and stability of nisin in cheese. The liposomal membrane may immobilize nisin by hydrophobic binding, resulting in the dense signals of gold-labeled antibodies to nisin observed along the inner surface of the membrane. The higher stability of nisin in liposome-containing cheese may also have been ensured by linear liposomal membranes, which may act as a reservoir for immobilized nisin in the cheese matrix during ripening.

Immobilization of nisin on liposome membranes may give nisin a higher stability by reducing its affinity for cheese components and reducing the accessibility to unfavorable conditions or elements in the surrounding environment. In all nisin degradation products, Dha residues (in particular the first ring at position 5) have been identified, indicating the importance of this group for the biological activity of the nisin peptide (16, 53). Nisin has a large hydrophobic section, with segments 1 to 19 being entirely hydrophobic except for Lys12, and it has been shown to be responsible for the insertion of the nisin peptide into the lipid membrane (29). Thus, the insertion of this portion into the liposome membranes may protect the Dha residues. Meanwhile, the association of nisin peptides with phospholipid membranes affects the conformation of the peptide and promotes the formation of β-turns (28). The formation of β-turns may be also responsible for the increased activity of liposome membrane-associated nisin, since structured nisin peptides show higher stability than do unstructured peptides molecules (21).

Our previous study showed that nisin was found inside liposome vesicles in two forms, either free in the encapsulated internal aqueous phase or immobilized along the inner liposome membrane (Laridi et al., submitted). This system might have a complementary effect and greater potential for cheese applications. Following cheese production, direct release of free nisin from the internal aqueous phase by opening of the liposome membrane would ensure a rapid reduction in viable counts of pathogenic organisms. However, membrane-immobilized nisin would be delivered over a longer term, providing continuous control of pathogenic and spoilage organisms during the ripening period. In the present study, immobilization of nisin Z on liposome membranes appeared to protect its activity and improve its availability and distribution in the cheese matrix. Adsorption of bacteriocins to various surfaces with retention of activity may be successfully achieved (10, 11, 21, 47). Membrane-immobilized nisin or surfaces could provide several advantages as a nisin delivery system, such as reducing the amount of nisin that would be used and improving its stability (20, 58). Nisin adsorbed to polyethylene used for meat packaging has been shown to be more stable and active against gram-positive pathogens and the food spoilage organisms L. monocytogenes and Brochothrix thermosphacta than was nisin applied directly in a free form (10, 11, 19, 20). Previous studies have shown that nisin adsorbed to lipid membranes can retain its antimicrobial activity and may have potential for use as a food grade antimicrobial agent (10, 11, 20, 56). The desorption of nisin from lipid membranes occurs on contact with bacterial cells (21).

Conclusion.

To our knowledge, this is the first report on the incorporation of liposome-encapsulated and/or -immobilized nisin Z in Cheddar cheese production. The use of anti-nisin Z monoclonal antibodies and TEM makes it possible to visualize nisin Z molecules in the cheese matrix and to gain insight into its inhibitory action against nisin-sensitive populations of lactococci, L. casei subsp. casei, and L. innocua. This is helpful in evaluating the mechanism of antibacterial activity of nisin Z in complex matrices such as Cheddar cheese. Cell membranes in nisin Z-sensitive lactococci appear to be the main nisin target, while the cytoplasm is the preferred site for nisin Z localization in L. casei subsp. casei and L. innocua. Cell wall digestion is the predominant effect of nisin Z in L. casei subsp. casei and L. innocua. Nisin Z appears to induce the formation of lysis vesicles in lactococci, L. casei subsp. casei, and L. innocua, suggesting the presence of a nisin-specific intracellular target. The difference in susceptibility and response to the inhibitory action of nisin Z demonstrated by the tested bacterial groups may indicate the existence of a genus- or species-specific nisin-inhibitory mechanism(s).

Liposomes appear to be suitable carriers for controlled nisin delivery and activity in cheese matrix. Entrapment in liposomes improves nisin stability, availability, and distribution in the cheese matrix. The existence of encapsulated and membrane-associated nisin may give this system a complementary effect, providing both short-term (by release of encapsulated nisin) and long-term (desorption of membrane-immobilized nisin) antibacterial action. This system may improve the control of undesirable bacteria in foods stored for long periods, such as cheese.

Acknowledgments

This research was carried out within the program of the Canadian Research Network on Lactic Acid Bacteria, supported by the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Novalait Inc., The Dairy Farmers of Canada, Rosell-Lallemand Inc., and the Fond pour les Chercheurs et l'Avancement de la Recherche from the Province of Quebec.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abad, A. R., K. R. Cease, and R. A. Blanchette. 1987. A rapid technique using epoxy resin Quetol 651 to prepare woody plant tissues for ultrastructural study. Can. J. Bot. 66:677-682. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abee, T., F. M. Rombouts, J. Hugenholtz, G. Guihard, and L. Letellier. 1994. Mode of action of nisin Z against Listeria monocytogenes Scott A grown at high and low temperatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1962-1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benech, R.-O., E. E. Kheadr, R. Laridi, C. Lacroix, and I. Fliss. 2002. Inhibition of Listeria in Cheddar cheese by addition of nisin Z in liposomes or in situ production by mixed culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3683-3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennik, M. H. J., A. Verheul, T. Abee, G. Naaktgeboren-Stoffels, L. G. Gorris, and E. J. Smid. 1997. Interactions of nisin and pediocin PA-1 with closely related lactic acid bacteria that manifest over 100-fold differences in bacteriocin sensitivity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3628-3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benz, R., G. Jung, and H. G. Sahl. 1991. Mechanism of channel formation by lantibiotics in black lipid membranes, p. 359-372. In G. Jung and H. G. Sahl (ed.), Nisin and novel lantibiotics. Escom Publishers, Leiden, The Netherlands.

- 6.Bierbaum, G., and H. G. Sahl. 1985. Induction of autolysis of staphylococci by the basic peptide antibiotics Pep5 and nisin and their influence on the activity of autolytic enzymes. Arch. Microbiol. 141:249-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bierbaum, G., and H. G. Sahl. 1987. Autolytic system of Staphylococcus simulans: influence of cationic peptides on activity of N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase. J. Bacteriol. 169:5452-5458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouksaim, M., I. Fliss, J. Meghrous, and R. E. Simard. 1998. Immunodot detection of nisin Z in milk and whey using enhanced chemoluminescence. J. Appl. Microbiol. 84:176-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouksaim, M., C. Lacroix, P. Audet, and R. E. Simard. 2000. Effect of mixed starter composition on nisin Z production by Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar. diacetylactis UL 719 during production and ripening of Gouda cheese. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 59:141-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bower, C. K., J. McGuire, and M. A. Daeschel. 1995. Suppression of Listeria monocytogenes colonization following adsorption of nisin onto silica surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:992-997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bower, C. K., J. McGuire, and M. A. Daeschel. 1995. Influences on the antimicrobial activity of surface-adsorbed nisin. J. Ind. Microbiol. 15:227-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breukink, E., C. van Kraaij, R. A. Demel, R. J. Siezen, O. P. Kuipers, and B. de Kruijff. 1997. The C-terminal region of nisin is responsible for the initial interaction of nisin with the target membrane. Biochemistry 36:6968-6976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breukink, E., I. Wiedemann, C. van Kraaij, O. P. Kuipers, H.-G. Sahl, and B. de Kruijff. 1999. Use of the cell wall precursor lipid II by a pore-forming peptide antibiotic. Science 286:2361-2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brötz, H., M. Josten, I. Wiedemann, U. Schneider, F. Götz, G. Bierbaum, and H.-G. Sahl. 1998. Role of lipid-bound peptidoglycan precursors in the formation of pore by nisin, epidermin and other lantibiotics. Mol. Microbiol. 30:317-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brötz, H., and H. G. Sahl. 2000. New insight into the mechanism of action of lantobiotics—diverse biological effects by binding to the same molecular target. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan, W. C., B. W. Bycroft, L. Y. Lian, and G. C. K. Roberts. 1989. Isolation and characterization of two degradation products derived from the peptide lantibiotic nisin. FEBS Lett. 252:29-36. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan, W. C., H. M. Dodd, N. Horn., K. Maclean, L.-Y. Lian, B. W. Bycroft, M. J. Gasson, and G. C. K. Roberts. 1996. Structure-activity relationships in the peptide antibiotic nisin: role of dehydroalanine 5. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:2966-2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crandal, A. D., and T. Montville. 1998. Nisin resistance in Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 700302 is a complex phenotype. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:231-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cutter, C. N., and G. R. Siragusa. 1996. Reduction of Listeria innocua and Brochothrix thermosphacta on beef following nisin spray treatments and vacuum packaging. Food Microbiol. 13:23-33. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cutter, C. N., and G. R. Siragusa. 1997. Growth of Brochothrix thermosphacta in ground beef following treatments with nisin in calcium alginate gels. Food Microbiol. 14:425-430. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daeschel, M. A., J. McGuire, and H. Al Makhlafi. 1992. Antimicrobial activity of nisin adsorbed to hydrophilic and hydrophobic silicon surfaces. J. Food Prot. 55:731-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daoudi, L., C. Turcotte, C. Lacroix, and I. Fliss. 2001. Production and characterization of anti-nisin Z monoclonal antibodies: suitability for distinguishing active from inactive forms through a competitive enzyme immunoassay. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 56:114-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delves-Broughton, J. 1990. Nisin and its application as a food preservative. J. Soc. Dairy Technol. 43:73-76. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delves-Broughton, J. 1990. Nisin and its uses as food preservative. Food Technol. 44:100-117. [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Man, J. C., M. Rogosa, and M. E. Sharpe. 1960. A medium for the cultivation of lactobacilli. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 23:130-135. [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Vos, W. M., J. W. Mulders, R. J. Siezen, J. Hugenholtz, and O. P. Kuipers. 1993. Properties of nisin Z and distribution of its gene, nisZ, in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:213-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Driessen, A. J., H. W. van den Hooven, W. Kuiper, M. van den Kamp, H. G. Sahl, N. H. Konings, and W. N. Konings. 1995. Mechanistic studies of lantibiotic-induced permeabilization of phospholipid vesicles. Biochemistry 34:1606-1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El Jastimi, R., and M. Lafleur. 1997. Structural characterization of free and membrane-bound nisin by infrared spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1324:151-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El Jastimi, R., and M. Lafleur. 1999. Nisin promotes the formation of non-lamellar inverted phases in unsaturated phosphatidylethanolamines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1418:97-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El Jastimi, R., K. Edwards, and M. Lafleur. 1999. Characterization of permeability and morphological perturbations induced by nisin on phosphatidylcholine membranes. J. Biophys. 77:842-852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao, F. H., T. Abee, and W. N. Konings. 1991. Mechanism of action of the peptide antibiotic nisin in liposomes and cytochrome c oxidase-containing proteoliposomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:2164-2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giffard, C. J., H. M. Dodd, N. Horn, S. Ladha, and A. R. Macki. 1997. Structure-function relations of variant and fragment nisin studied with model membrane systems. Biochemistry 36:3802-3810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guerzoni, M. E., L. Vannini, C. Chaves Lopez, R. Lanciotti, G. Suzzi, and A. Gianotti. 1999. Effect of high pressure homogenization on microbial and chemico-physical characteristics of goat cheeses. J. Dairy Sci. 82:851-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jung, D.-S., F. W. Bodyfelt, and M. A. Daeschel. 1992. Influence of fat and emulsifiers on the efficacy of nisin in inhibiting Listeria monocytogenes in fluid milk. J. Dairy Sci. 75:387-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kempler, G. M., and L. L. McKay. 1980. Improved medium for detection of citrate fermenting Streptococcus lactis ssp. diacetylactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 4:926-927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kheadr, E. E., J. C. Vuillemard, and S. A. El Deeb. 2000. Accelerated Cheddar cheese ripening with encapsulated proteinases. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 35:483-495. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kosikowski, F. V. 1982. Cheddar cheese, p. 228-260. In F. V. Kosikowski (ed.), Cheese and fermented milk foods, 3rd ed. F. V. Kosikowski and Associates, Brookdontale, New York, N.Y.

- 38.Laloy, E., J. C. Vuillemard, and R. E. Simard. 1998. Characterization of liposomes and their effect on the properties of Cheddar cheese during ripening. Lait 78:401-412. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lins, L., P. Ducarme, E. Breukink, and R. Brasseur. 1999. Computational study of nisin interaction with model membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1420:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin, I., J. M. Ruysschaert, D. Sanders, and C. Giffard. 1996. Interaction of the lantibiotic nisin with membranes revealed by fluorescence quenching of an introduced tryptophan. Eur. J. Biochem. 239:156-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martínez-Cuesta, M. C., P. F. de Palencia, T. Requena, and C. Pealaez. 1998. Enhancement of proteolysis by a Lactoccocus lactis bacteriocin producer in a cheese model system. J. Agric. Food Chem. 46:3863-3867. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martínez-Cuesta, M. C., J. Kok, E. Herranz, C. Peláez, T. Requena, and G. Buist. 2000. Requirement of autolytic activity for bacteriocin-induced lysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3174-3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McAuliffe, O., R. P. Ross, and C. Hill. 2000. Lantibiotics: structure, biosynthesis and mode of action. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 714:1-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCafferty, D. G., P. Cudic, M. K Yu, D. C. Behenna, and R. Kruger. 1999. Synergy and duality in peptide antibiotic mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 3:672-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meghrous, J., C. Lacroix, M. Bouksaim, G. Lapointe, and R. E. Simard. 1997. Genetic and biochemical characterization of nisin Z produced by Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis biovar. diacetylactis UL 719. J. Appl. Microbiol. 83:133-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ming, X., and M. A. Daeschel. 1995. Correlation of cellular phospholipid content with nisin resistance of Listeria monocytogenes Scott A. J. Food Prot. 58:416-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ming, X., G. H., Weber, J. W. Ayres, and W. E. Sandine. 1997. Bacteriocins applied to food packaging materials to inhibit Listeria monocytogenes on meats. J. Food Sci. 62:413-415. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moll, G. N., J. Clark, W. C. Chan, B. W. Bycroft, and G. C. K. Roberts. 1997. Role of transmembrane pH gradient and membrane binding in nisin pore formation. J. Bacteriol. 179:135-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moll, G. N., W. N. Konings, and A. J. M. Driessen. 1998. The lantibiotic nisin induces transmembrane movement of a fluorescent phospholipid. J. Bacteriol. 180:6565-6570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mulders, J. W., I. J. Boerrigter, H. S. Rollema, R. J. Siezen, and W. M. De Vos. 1991. Identification and characterization of the lantibiotic nisin Z, a natural nisin variant. Eur. J. Biochem. 201:581-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ojcious, D. M., and J. D. Young. 1991. Cytolytic pore forming proteins and peptides: is there a common structural motif? Trends Biochem. Sci. 16:225-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reisinger, P., H. Seidel, H. Tschesche, and W. P. Hammes. 1980. The effect of nisin on murein synthesis. Arch. Microbiol. 127:187-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rollema, H. S., P. Both, and R. J. Siezen. 1991. NMR and activity studies of nisin degradation products, p. 123-130. In G. Jung and H. G. Sahl (ed.), Nisin and novel lantibiotics. Escom Publishers, Leiden, The Netherlands.

- 54.Ruhr, E., and H. G. Sahl. 1985. Mode of action of the peptide antibiotic nisin and influence on the membrane potential of whole cells and cytoplasmic and artificial membrane vesicles. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 27:841-845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sahl, H. G., and G. Bierbaum. 1998. Lantibiotics: biosynthesis and biological activities of uniquely modified peptides from Gram-positive bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:41-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scannel, A. G., C. Hill, R. P. Ross, S. Marx, M. E. Hartmayer, and K. Arendt. 2000. Development of bioactive food packaging material using immobilized bacteriocin lacticin 3147 and nisaplin. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 60:241-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Severina, E., A. Severin, and A. Tomasz. 1998. Antibacterial efficacy of nisin against multidrug-resistant Gram-positive pathogens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 41:341-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siragusa, G. R., C. N. Cutter, and J. L. Willet. 1999. Incorporation of bacteriocin in plastic retains activity and inhibits surface growth of bacteria on meat. Food Microbiol. 16:229-235. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Terzaghi, B. E., and W. E. Sandine. 1975. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 29:807-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van den Hooven, H. W., C. C. M. Doeland, M. van de Kamp, R. N. H. Konings, C. W. Hilbers, and F. J. M. van de Ven. 1996. Three-dimensional structure of the lantibiotic nisin in the presence of membrane-mimetic micelles of dodecylphosphocholine and of sodium dodecylsulphate. Eur. J. Biochem. 235:382-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Verheul, A., N. J. Russell, R. V. Hof, F. M. Rombouts, and T. Abee. 1997. Modifications of membrane phospholipid composition in nisin-resistant Listeria monocytogenes Scott A. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3451-3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wiedemann, I., E. Breukink, C. van Kraaij, O. P. Kuipers, G. Bierbaum, B. de Kruijff, and H. G. Sahl. 2001. Specific binding of nisin to the peptidoglycan precursor lipid II combines pore formation and inhibition of cell wall biosynthesis for potent antibiotic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 276:1772-1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Winkowski, K., M. E. Bruno, and T. J. Montville. 1994. Correlation of bioenergetic parameters with cell death in Listeria monocytogenes cells exposed to nisin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:4186-4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]